Introduction

Complementary and alternative medicine is used by individuals in many and varied contexts, including those with chronic conditions, for illness prevention, dissatisfaction with conventional medicine or where conventional treatments are limited.Reference Harris, Cooper, Relton and Thomas 1 , Reference Fischer, Lewith, Witt, Linde, von Ammon and Cardini 2 Research into factors influencing the use of complementary and alternative medicine indicates that its use is higher in health economies where access to medical services is poor.Reference Harris, Cooper, Relton and Thomas 1 In more affluent health economies, higher complementary and alternative medicine use has been associated with female gender, higher educational status, middle age and poorer health status.Reference Harris, Cooper, Relton and Thomas 1

A 2014 study by Fischer et al. indicated that the use of complementary and alternative medicine has risen in Western industrial countries over the past 25 years.Reference Fischer, Lewith, Witt, Linde, von Ammon and Cardini 2 However, a systematic review by Harris et al., published in 2012, found that the use of complementary and alternative medicine had not risen between 2000 and 2012.Reference Harris, Cooper, Relton and Thomas 1 Once prayer is excluded, the most common complementary and alternative medicine interventions utilised are chiropracty, herbal medicine and homeopathy.Reference Frass, Strassl, Friehs, Muller, Kundi and Kaye 3 The complementary and alternative medicine usage rates reported are variable within and between countries, and are influenced by survey design.Reference Posadzki, Watson, Alotaibi and Ernst 4 In the UK, a review of large scale surveys indicated a mean one year prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine uptake in adults of 39.9 per cent (range, 10–100 per cent), and a mean lifetime prevalence of 58.7 per cent (range, 44–71 per cent).Reference Posadzki, Watson, Alotaibi and Ernst 4 The use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with audiovestibular symptoms and disorders has been noted, specifically in cases of imbalance,Reference Baguley, Humphriss, Butler, Knight, Dawson and Vickers 5 tinnitusReference Andersson 6 , Reference Wolever, Price, Hazelton, Dmitrieva, Bechard and Shaffer 7 and hearing loss,Reference Low 8 although to the authors’ knowledge there is no randomised controlled trial evidence to support any specific therapy.

The attitudes of physicians towards complementary and alternative medicine, and knowledge regarding common complementary and alternative medicine therapies, have begun to be explored in the literature. Initial findings indicate that attitudes are broadly positive, though studies to date have been rather non-specific.Reference Frass, Strassl, Friehs, Muller, Kundi and Kaye 3 An objective of the present study was to determine the attitude to complementary and alternative medicine of clinical staff working with patients with audiovestibular disorders. This is of interest, as a dismissive attitude may dissuade patients from exploring therapies that may potentially yield benefit. Such benefits may be direct, wherein therapies address the symptoms themselves, or indirect, providing relaxation or increased sensations of well-being. Another aim was to determine whether clinicians working with patients with audiovestibular disorders use complementary and alternative medicine themselves, and whether such use is dissonant with advice given to patients.

Materials and methods

In order to determine attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine, clinical staff working in university hospital otolaryngology and audiology departments were given two questionnaires: one developed for this study, which enquired about the demographics and personal complementary and alternative medicine use of the respondent (Appendix 1), and the Holistic Complementary and Alternative Medicine Questionnaire (‘HCAMQ’).Reference Hyland, Lewith and Westoby 9

The Holistic Complementary and Alternative Medicine Questionnaire was developed to measure two related psychological variables, namely attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine and holistic health beliefs. This questionnaire has been psychometrically validated, with good test–retest reliability.Reference Hyland, Lewith and Westoby 9 However, the original proposed two-factor structure, with subscales indicating attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine and to holistic health, has been supplanted by a revised two-factor structure using shortened subscales for these variables.Reference Kersten, White and Tennant 10 A low score (minimum score of 1) indicates a more positive attitude towards complementary and alternative medicine and holistic health; the maximum score of 6 indicates an extremely negative attitude.

In a follow-on assessment, clinicians were asked if they would recommend complementary and alternative medicine to patients, and to friends.

Results

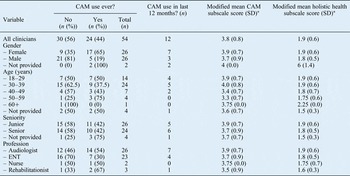

Of 81 questionnaires, 54 were completed, giving a return rate of 67 per cent. Genders were evenly distributed, with 26 (48 per cent) female respondents and 26 (48 per cent) male respondents; 2 respondents (4 per cent) did not provide gender details. The sample included an even distribution of professions and seniority levels. The majority of respondents (70 per cent) were aged under 40 years (Table I).

Table I Summary of CAM use data and questionnaire results

* Low scores (minimum score of 1) indicate a more positive attitude towards complementary and alternative medicine and holistic health; the maximum score of 6 indicates an extremely negative attitude. CAM = complementary and alternative medicine; SD = standard deviation

Thirty participants (56 per cent) had never used complementary and alternative medicine. Of the 24 (44 per cent) that had used it previously, 12 (50 per cent) had done so in the last 12 months. Seventy-nine per cent of those who had used complementary and alternative medicine were satisfied with the outcomes.

The results indicate that complementary and alternative medicine use was significantly more common in females (p = 0.002, chi-square test), but there was no significant difference in use when comparing age (p = 0.6), seniority (p = 0.8) or profession (p = 0.17, Fisher's exact test).

The mean score on the complementary and alternative medicine modified subscale of the Holistic Complementary and Alternative Medicine Questionnaire was 3.8 (standard deviation (SD) = 0.8) and the mean score on the holistic health subscale was 1.9 (SD = 0.6).

Twenty-five clinicians answered the follow-up questions about recommendation of complementary and alternative medicine to friends and family. All (100 per cent) of the clinicians who had used complementary and alternative medicine had recommended it to friends, compared to only 19 per cent (3 of 16) of those who had not used complementary and alternative medicine.

Thirty-three per cent (n = 3) of clinicians who had used complementary and alternative medicine had recommended it to patients, compared to 31 per cent (n = 5) who had not used complementary and alternative medicine. Details were provided by seven of the eight individuals who had recommended complementary and alternative medicine regarding the types of therapies recommended. Responses included: mindfulness, osteopathy, relaxation (n = 3 each), acupuncture for migraine and facial pain, and exercise such as Pilates, Forever Active and tai chi (n = 2 each).

Eleven per cent (n = 1) of clinicians who had used complementary and alternative medicine had advised patients against using it, compared to 38 per cent (n = 6) of those who had not used complementary and alternative medicine. Individuals were equally likely to recommend complementary and alternative medicine to patients regardless of their satisfaction with the results of personal use. Details were provided by six of the seven individuals who had advised individuals against the use of complementary and alternative medicine regarding the types of therapies not recommended. Responses included Hopi candles (n = 6), and Eastern or complimentary medicine for ear infections (n = 2).

Discussion

Given the small sample size of the study, the authors acknowledge that the results should be interpreted with caution. The results for our sample are in line with previous research suggesting that complementary and alternative medicine use is higher in females.Reference Harris, Cooper, Relton and Thomas 1 Personal complementary and alternative medicine use was broadly similar across different professional groups, though there was a trend for lower use by ENT clinicians. The specialty of ENT is typically dominated by men (89 per cent),Reference Choi and Miller 11 whereas other professions are typically dominated by women (e.g. audiology (80 per cent), nursing (90.4 per cent) and rehabilitation). 12 , 13 In the study sample, the proportion of men in ENT (83 per cent) and women in audiology (72 per cent) were comparable to national data.

As a university teaching hospital, there is a high proportion of younger staff in the sample, which may explain why the results do not demonstrate a higher use of complementary and alternative medicine in middle age as has previously been reported.Reference Harris, Cooper, Relton and Thomas 1

Attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine were slightly negative (score of 3.8 on a scale of 1–6), but were moderately positive towards holistic health (score of 1.9 on a scale of 1–6). There was a somewhat lower personal use of complementary and alternative medicine in the sample group (44 per cent) when compared to the reported UK average (58.7 per cent).Reference Posadzki, Watson, Alotaibi and Ernst 4

Individuals who had used complementary and alternative medicine previously were more likely to recommend it to friends (100 per cent) than patients (33 per cent). There was no link between satisfaction with complementary and alternative medicine and the propensity to recommend it to patients. Notably, individuals who had not used complementary and alternative medicine previously were more likely to recommend it to patients (31 per cent) than friends (19 per cent). They were also more likely to advise patients against its use. This may be explained by a lack of knowledge about complementary and alternative medicine. Individuals working within healthcare need to be aware of complementary and alternative therapies, so they can appropriately advise patients on their use.

-

• Complementary and alternative medicine is used by individuals in many and varied contexts

-

• In more affluent health economies, its use is associated with female gender, higher educational status, middle age and poorer health status

-

• In this study, complementary and alternative medicine use was higher in females, but there was no difference in use when comparing age, seniority or profession

-

• Attitudes were slightly negative towards complementary and alternative medicine, and moderately positive towards holistic health

-

• Individuals who had used complementary and alternative medicine were more likely to recommend it to friends than patients

-

• There was no link between complementary and alternative medicine satisfaction and propensity to recommend it to patients

Future research into the use of, and attitudes towards, complementary and alternative medicine in ENT and audiology professionals could consider the use of such medicine by professionals who have subspecialised. Research might focus on use and attitudes in those concerned with treating tinnitus and imbalance, as complementary and alternative medicine has been reported in those patient populations.

Appendix 1. Complementary and alternative medicine survey

We are undertaking a survey of attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) amongst professionals working in Audiology, ENT and Hearing Implants. We define CAM as a procedure or preparation not associated with traditional Western medicine taken for a medical symptom or condition.

Thank you for completing this front sheet and enclosed questionnaire.

-

1. Your age: (years)

-

2. Gender: Male / Female

-

3. Profession: Audiologist / ENT / Nursing / Rehabilitationist

-

4. Grade: Trainee / Junior / Senior / Very senior

-

5. Have you ever used a complementary or alternative therapy? Yes / No

If yes:

-

(a) Have you used CAM in the last 12 months? Yes / No

-

(b) Were you satisfied with the results? Yes / No

-

-

6. Have you ever recommended CAM to a friend or relative? Yes / No

-

7. Have you ever recommended CAM to a patient? Yes / No

If yes, please provide details:

……………

……………

-

8. Have you ever advised a patient against using CAM? Yes / No

If yes, please provide details:

……………

……………