Introduction

Peritonsillar infection is a common reason to seek an ENT clinic. It refers to infection of the tissue between the capsule of the palatine tonsil and the pharyngeal muscles, called peritonsillar cellulitis, often complicated with an abscess.Reference Paras, Durand and Deschler1 Peritonsillar abscess has an annual incidence of 37 per 100 000 in Sweden.Reference Risberg, Engfeldt and Hugosson2 The distinction between peritonsillar cellulitis and peritonsillar abscess is not always obvious before diagnostic needle aspiration is performed; hereafter, the term ‘peritonsillar infection’ refers to both these conditions.

Patients suffering from peritonsillar infection typically present with throat pain, trismus, muffled voice, dysphagia, fever, swollen or tender lymph nodes on the affected side, and sometimes also oedema of the larynx or hypopharynx.Reference Paras, Durand and Deschler1 Treatment varies between countries, clinics, doctors and patients,Reference Powell and Wilson3–Reference Mehanna, Al-Bahnasawi and White6 but usually includes oral or intravenous antibiotics combined with needle aspiration or incision and drainage if an abscess is present. Acute or subacute tonsillectomy, called tonsillectomy à chaud, is also a treatment alternative.Reference Simon, Matijasec, Perry, Kakade, Walvekar and Kluka7

Abscesses are often polymicrobial with both aerobes and anaerobes.Reference Brook8–Reference Powell, Powell, Samuel and Wilson11 As non-infected tonsils are heavily colonised, the pathogenic relevance of microbial findings is difficult to prove. There is substantial evidence that Streptococcus pyogenes is a pathogen causing peritonsillar infection, but several other bacteria are suggested to have a pathogenic role.Reference Klug, Henriksen, Fuursted and Ovesen9,Reference Powell, Powell, Samuel and Wilson11,Reference Klug12 Based on microbial studies, broad-spectrum antibiotics or combinations of antibiotics have been proposed for the primary empirical treatment of peritonsillar infectionReference Powell and Wilson3,Reference Acharya, Gurung, Khanal and Ghimire10,Reference Powell, Powell, Samuel and Wilson11,Reference Repanos, Mukherjee and Alwahab13 rather than using penicillin V or G alone (hereafter referred to as penicillin). The American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery suggests the broad-spectrum antibiotic clindamycin as the primary choice for treating deep neck space abscesses, including peritonsillar abscesses.Reference Fairbanks14

However, studies comparing penicillin alone with broad-spectrum antibiotics or combinations of antibiotics have shown the same time to recovery and rate of recurrence.Reference Tuner and Nord15–Reference Kieff, Bhattacharyya, Siegel and Salman17 In 1999, Kieff et al. retrospectively studied the choice of antibiotics after incision and drainage of peritonsillar abscesses, comparing intravenous penicillin with intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics (with 43 of 58 patients in the broad-spectrum group having received clindamycin) and found no significant difference in either recovery or recurrence.Reference Kieff, Bhattacharyya, Siegel and Salman17 Moreover, several studies describe clindamycin resistance in S pyogenes in cultures from variable sites,Reference DeMuri, Sterkel, Kubica, Duster, Reed and Wald18–Reference Pesola, Sihvonen, Lindholm and Patari-Sampo20 including peritonsillar abscesses.Reference Sowerby, Hussain and Husein21 Penicillin resistance has not been observed in S pyogenes.Reference Macris, Hartman, Murray, Klein, Roberts and Kaplan22–Reference Abraham and Sistla24

It is reasonable to believe that increased use of clindamycin enhances the risk of selection of resistant bacterial strains in both Streptococci and other bacteria. It is known that clindamycin, in comparison to penicillin, has a significantly more profound and long-lasting effect on the intestinal microbiotaReference Rashid, Zaura, Buijs, Keijser, Crielaard and Nord25 and that this collateral damage results in increased antibiotic resistance.Reference Zimmermann and Curtis26 Clindamycin also has more adverse effects than penicillin does, including potentially fatal intestinal infection with Clostridium difficile.Reference Brindle, Williams, Davies, Harris, Jarman and Hay27–Reference Thornhill, Dayer, Durkin, Lockhart and Baddour32

The aim of this study was to investigate and compare treatment with clindamycin versus penicillin in terms of time to recovery in patients with peritonsillar infection, including both peritonsillar cellulitis and peritonsillar abscess. The secondary aim was to investigate whether treatment with clindamycin versus penicillin reduces the frequency of recurrence of peritonsillar infection within two months.

Materials and methods

Participants

This retrospective cohort study examined the medical records of 296 patients seen for peritonsillar infection during 2015–2017 at Södra Älvsborg Hospital, a secondary-care hospital in Sweden with a catchment population of about 300 000 people. The ENT clinic in this hospital is the only ENT facility in the area treating peritonsillar infection, which is why we believe that almost all cases of peritonsillar infection in the area are treated here. Most of the patients were admitted to the hospital from primary care, and several patients had already received antibiotics from a general practitioner before visiting the ENT clinic. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg.

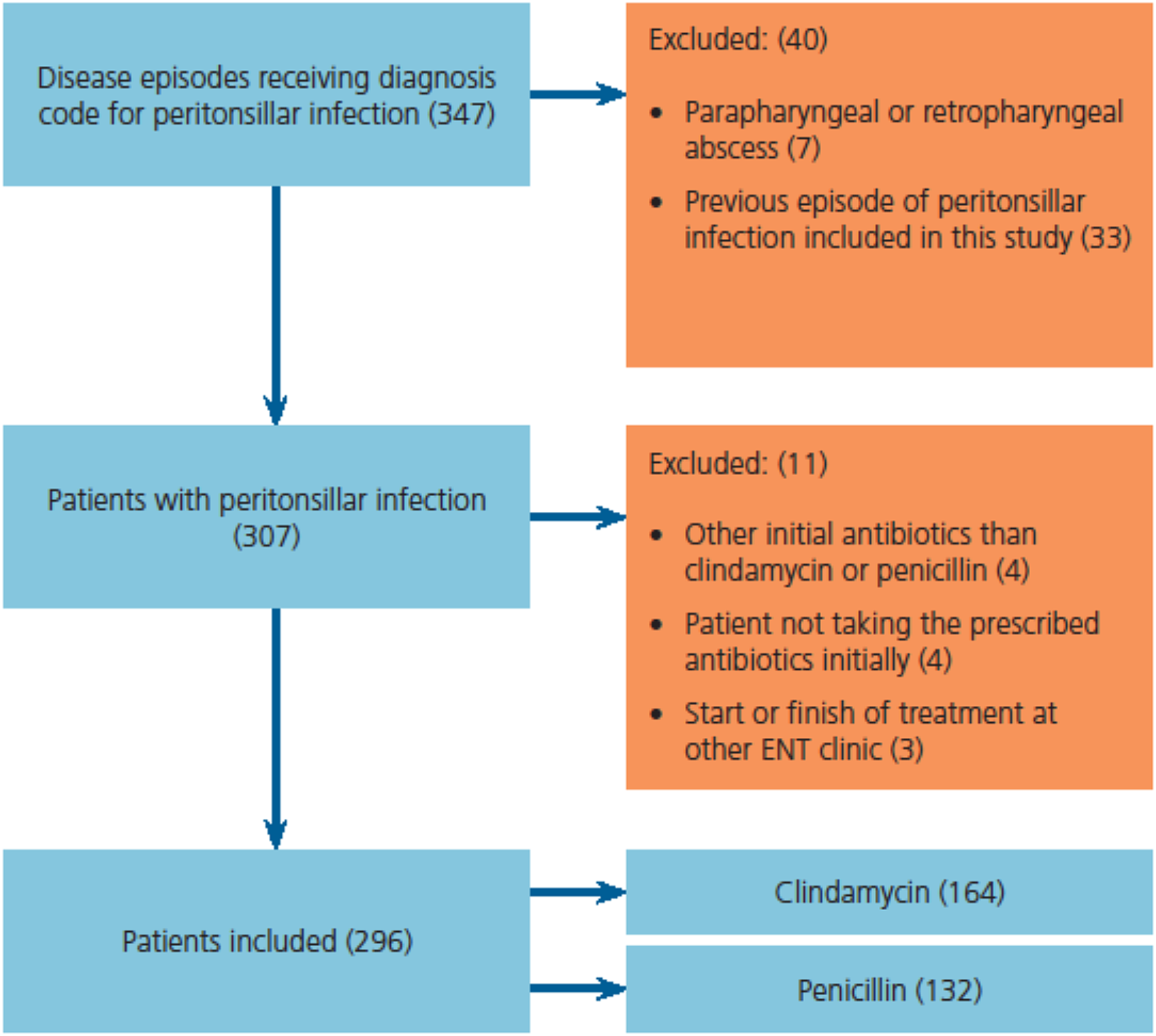

All patients receiving the diagnosis code for peritonsillar infection were assessed for eligibility. Data were collected exclusively from the medical records of the ENT clinic. Based on the choice of antibiotics at the first ENT visit, patients diagnosed with peritonsillar infection were retrospectively divided into clindamycin and penicillin groups. Patients with a parapharyngeal or retropharyngeal abscess were not included. Only the first episode of peritonsillar infection during the study period was included, so no patients were included more than once. The inclusion process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of inclusion process.

Routine management of peritonsillar infection in adults and older children at this ENT clinic was with antibiotics and, in cases of suspected abscess, diagnostic aspiration followed by incision and drainage if purulence was identified. Most were treated as out-patients with oral treatment, and a smaller proportion as in-patients with intravenous treatment. Re-drainage of the abscess was routine even if the patient was improving and was normally performed daily or every two days until purulence could no longer be identified.

The routine choice of antibiotics was clindamycin or penicillin, and the choice between these was made by the doctor treating the patient and most often not motivated in the medical record. For oral treatment with clindamycin, the dose was 300 mg 3 times daily, and for intravenous treatment, the dose was 600 mg 3 times daily. For oral treatment with penicillin V, the dose in most cases was 1000 mg 3 times daily, and for intravenous treatment with penicillin G, the dose was 3000 mg 3 times daily. Routine management of peritonsillar infection in younger children was in-patient treatment with intravenous antibiotics dosed at 30–40 mg kg–1 daily for clindamycin, and 140–150 mg kg–1 daily for penicillin G. For both adults and children, tonsillectomy à chaud was used when the above treatment was insufficient. The number of patients treated with intravenous antibiotics can be found in Table 1.

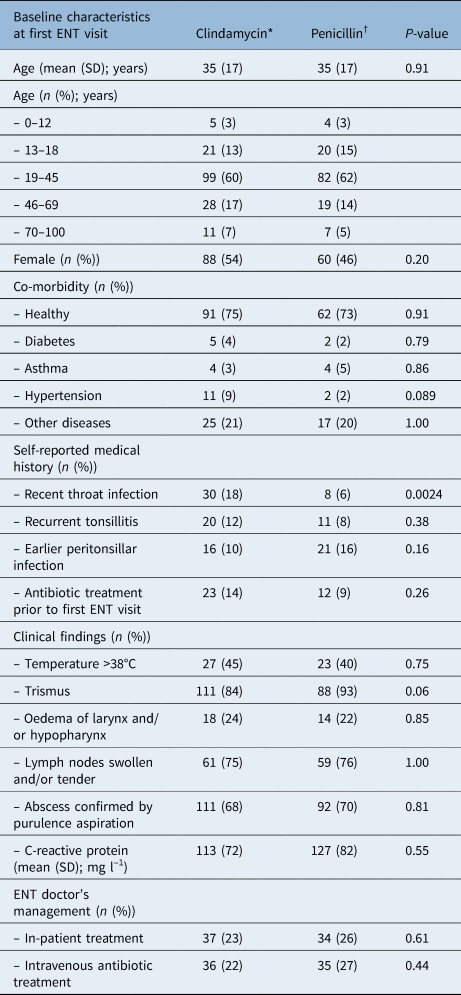

Table 1. Baseline characteristics at first ENT visit for patients in the clindamycin versus penicillin groups

P-values compare the penicillin and clindamycin groups. *n = 164; †n = 132. SD = standard deviation

Characteristics

The clindamycin and penicillin groups were compared in terms of baseline characteristics at first ENT visit, (i.e., age, sex, co-morbidity, self-reported medical history, clinical and laboratory findings, and ENT doctor's management). Comparison between groups was also conducted for microbes found in cultures of abscess and throat swabs.

Time to recovery and recurrence

The primary outcome was time to recovery measured as the number of days in follow up at the ENT clinic. This refers to the length of admission or the number of days until the last day the patient was seen in the ENT clinic. The day of the first medical appointment at the ENT clinic was included in the number of days. For in-patients, day of discharge was considered the last day of follow up if no further visits were made.

Secondary outcome measures were number of visits to the ENT clinic, number of drainages with purulence identification, frequency of tonsillectomy à chaud and recurrence within two months. Only out-patients were included in the analysis of number of visits. Patients treated with tonsillectomy à chaud were not included in the outcome measures of days of follow up, number of visits or number of drainages with purulence identification. Recurrence was defined as a patient re-attending the ENT clinic within two months following a symptom-free interval, presenting with a new case of peritonsillar infection requiring treatment.

Subgroups

The following subgroups were analysed: confirmed peritonsillar abscess at first ENT visit, peritonsillar cellulitis with no confirmed abscess at first ENT visit, initial in-patient treatment, initial out-patient treatment, females, males and patients with negative rapid antigen detection test results for S pyogenes. In the subgroup of peritonsillar cellulitis with no confirmed abscess by pus aspiration at first ENT visit, we also analysed the frequency of later purulence identification by aspiration or incision. In the subgroup of initial out-patient treatment, we also analysed the need for later in-patient treatment due to impairment, lack of recovery or adverse effects.

Statistical methods

For statistical analysis, Fisher's exact test (lowest one-sided p-value multiplied by two) was used for dichotomous variables, the Mann–Whitney U test was used for continuous variables and the Mantel–Haenszel chi-square test was used for ordered categorical variables. Dichotomous variables are presented as numbers and percentages, and continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations.

For the outcome variables, the differences between means or percentage points and confidence intervals (CI) are presented. For dichotomous variables, the CI is the unconditional exact confidence limit, whereas for continuous variables, the CI was calculated based on bootstrapping. Logistic regression was used to adjust for differences between groups, presented in the Results and Discussion sections but not in the tables.

For self-reported medical history, data that were not present in medical records were assumed to be negative, so percentages were calculated based on all patients. For co-morbidity, clinical findings and C-reactive protein, percentages were calculated based only on the patients for whom data were available. A level of significance of p < 0.05 was used in all analyses. Statistical analysis was performed by a professional statistician and the authors using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, USA).

Results

Characteristics, recovery and recurrence

A total of 164 (55 per cent) of the patients received clindamycin and 132 (45 per cent) received penicillin at first visit to the ENT clinic for treatment of peritonsillar infection. These groups were comparable in terms of age, sex, co-morbidity, clinical findings and C-reactive protein (Table 1).

There were no significant differences in either recovery or recurrence in the patients treated with clindamycin compared with penicillin (Table 2). The mean number of days in follow up was 3.5 in the clindamycin group and 3.4 in the penicillin group. The mean number of visits was 2.8 in the clindamycin group and 2.8 in the penicillin group. The recurrence rate within 2 months was 7 per cent in the clindamycin group and 4 per cent in the penicillin group.

Table 2. Outcome measures for patients treated with clindamycin compared with penicillin

P-values and differences between means or percentage points comparing the penicillin and clindamycin groups. *n = 164; †n = 132. CI = confidence interval; SD = standard deviation

Significantly more patients reporting a recent throat infection in their medical history, defined as the past three months, received treatment with clindamycin (p < 0.01). When adjusting for this difference in characteristics, there were still no significant differences in the outcomes. No other significant differences were found in the characteristics. The microbial findings in cultures were similar in the clindamycin and penicillin groups (Table 3). No antibiotic sensitivity test results are presented, since microbial findings are only intended to serve as a comparison between the groups.

Table 3. Bacterial findings in cultures from abscess or throat of patients in the clindamycin compared with penicillin groups

Cultures were not available for all patients. Percentage of bacteria recovered calculated from patients with available cultures. P-values comparing the penicillin and clindamycin groups. *n = 59 abscess; n = 22 throat; †n = 66 abscess; n = 27 throat

Subgroups

There were no differences in either recovery or recurrence in any of the analysed subgroups: confirmed peritonsillar abscess at first ENT visit, peritonsillar cellulitis with no confirmed abscess at first ENT visit, initial in-patient treatment, initial out-patient treatment, females, males and 42 patients with a negative rapid antigen detection test for S pyogenes. In the subgroup of peritonsillar cellulitis with no confirmed abscess at first ENT visit, there was no difference between the clindamycin and penicillin groups in terms of later purulence identification by aspiration. In the subgroup of initial out-patient treatment, there was no difference between the clindamycin and penicillin groups in terms of the need for later in-patient treatment because of impairment, lack of improvement or adverse effects.

Change of antibiotics

Seven patients in the clindamycin group and twelve patients in the penicillin group had their antibiotics changed during treatment for various reasons, so a per-protocol analysis was performed by excluding these patients, which showed no significant differences in outcome. Results presented in the tables and text include all these patients. Of the seven changes of antibiotics in the clindamycin group, four were made because of suspicion of allergy or adverse effects, two because of insufficient recovery and one because of breast feeding. Of the twelve changes of antibiotics in the penicillin group, eight were made without any reason being mentioned in the medical chart (in most cases after some recovery when switching from intravenous to oral treatment), three because of insufficient recovery and one because of growth of gram-negative bacteria in culture.

Adverse effects

Since this study is retrospective, adverse effects and allergy could not be included in the outcome. It is probable that patients have experienced adverse effects without contacting the ENT clinic, or that the ENT doctor has not reported expected adverse effects in the medical records. Only five cases of suspected adverse effects or allergy are documented in the medical records. For clindamycin, four cases of rash, itch, face swelling or stomach pain were noted, and all led to a change of antibiotics. For penicillin, one case of a vomit is noted but the antibiotic was not changed. It appears from medical records, although not always stated clearly, that all suspected adverse effects passed without sequelae.

Discussion

When comparing treatment with clindamycin and treatment with penicillin among patients with peritonsillar infection, no differences were found between the two antibiotics regarding either time to recovery or the recurrence rate of the condition. Given equal outcomes, choosing penicillin instead of clindamycin has several advantages. We argue that penicillin is the preferable choice because of lower frequency of adverse effects shown in previous studies, including C difficile infectionsReference Brindle, Williams, Davies, Harris, Jarman and Hay27–Reference Thornhill, Dayer, Durkin, Lockhart and Baddour32 and a less pronounced effect on the intestinal microbiotaReference Rashid, Zaura, Buijs, Keijser, Crielaard and Nord25 resulting in less development of antibiotic resistance.Reference Zimmermann and Curtis26

Both patients with a confirmed peritonsillar abscess and patients with peritonsillar cellulitis without a confirmed abscess, were included in the study. Subgroup analysis was performed for the patients in whom purulence was identified by diagnostic aspiration at the first ENT visit (i.e. with a confirmed abscess) and no significant differences in either recovery or recurrence were found between the clindamycin and penicillin groups. Subgroup analysis was also performed for the more heterogeneous group of patients in whom no diagnostic aspiration was performed or in whom no purulence was identified by aspiration and, again, no significant differences in outcome were found between the clindamycin and penicillin groups. We did not find any significant difference in the frequency of later identification of purulence, implying that there is no difference in the ability of the antibiotics to prevent abscess formation. This would appear to support the use of penicillin for both confirmed peritonsillar abscess and peritonsillar cellulitis.

Significantly more patients in the group prescribed clindamycin had reported a recent throat infection. When adjusting for this difference, there were still no significant differences in the outcome. A possible reason for this difference in characteristics is that it has been shown that clindamycin reduces the number of recurrent tonsillitis cases, leading to national Swedish clinical guidelines supporting clindamycin as the primary treatment for recurrent tonsillitis.33,Reference Munck, Jorgensen and Klug34 It is reasonable to assume that this sometimes affects the doctor's choice of antibiotics when treating peritonsillar infection as well. To our knowledge, it has not been shown that clindamycin reduces the number of recurrent cases of peritonsillar infection, and in this study we found no difference in such recurrence. There was no difference between the groups regarding reporting recurrent tonsillitis, or earlier peritonsillar infection.

Since this study is retrospective, considerable information on patient characteristics may be missing. It was impossible to control for compliance or include any outcome measures related to patient experience, such as symptom relief or adverse effects. The study is small, and it should be noted that some outcome measures did not cover all patients, which diminishes the material, as described in the Materials and Methods section.

• Peritonsillar infection is usually treated with antibiotics, and in cases of suspected abscess, needle aspiration sometimes followed by incision and drainage. Tonsillectomy is also a treatment alternative

• Peritonsillar abscesses are often polymicrobial leading to recommendations of broad-spectrum antibiotics such as clindamycin

• Previous clinical studies have shown similar outcomes between penicillin and broad-spectrum antibiotics, or combinations of antibiotics

• This retrospective cohort study found no differences in time to recovery or frequency of recurrence between penicillin and clindamycin in treatment of peritonsillar infection

• Clindamycin has more adverse effects and a greater impact on the intestinal microbiota and antibiotic resistance than penicillin

• This supports use of penicillin as a first-line treatment of peritonsillar infection, with or without peritonsillar abscess

We considered selection bias a substantial risk in the study. That is why we compared the groups in terms of a large number of baseline characteristics, in order to find out whether more seriously ill patients received the broad-spectrum antibiotic clindamycin. Apart from the characteristic of reporting a recent throat infection, as mentioned above, no such result was found.

Conclusion

Patients with peritonsillar infection were retrospectively analysed regarding outcome after treatment with clindamycin or penicillin, showing no significant differences in either recovery or frequency of recurrence. Considering the greater adverse effects of clindamycin shown in previous studies, as well as its greater effect on the intestinal microbiota resulting in increased antibiotic resistance, this study supports the use of penicillin as a first-line treatment in patients with peritonsillar infection with or without peritonsillar abscess.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Mattias Molin, statistician at Södra Älvsborg Hospital Department of Research, for assistance in the statistical analysis and Claes Henning at Södra Älvsborg Hospital Department of Microbiology for participation in microbiological discussions. This work was funded by the Local Research and Development Council, Södra Älvsborg, and Södra Älvsborg Hospital Department of Research.

Competing interests

None declared