Introduction

A cardinal principle of surgery is the identification of a structure in order to avoid injuring it. This certainly applies to the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, the identification of which is an important step in thyroid surgery. The external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve innervates the cricothyroid muscle which is the tensor of the vocal fold. The nerve runs close to the upper pole of the thyroid gland and is at risk of injury during dissection. Traditionally, more importance has been given to the recurrent laryngeal nerve,Reference Roy, Gardiner and Niblock1 and there is often a tendency to ignore the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. In recent years, however, there has been increasing awareness about the importance of preserving the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve in thyroid surgery in order to avoid deterioration of voice quality. There has also been a greater understanding of the anatomy of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve in relation to the thyroid gland.

The superior laryngeal nerve originates from the middle of the nodose ganglion. It receives contributions from the superior cervical sympathetic ganglion. Its path of descent initially begins posteriorly and proceeds medially to the internal carotid artery where it bifurcates into an internal (sensory and autonomic) and external (motor) branch. The internal branch pierces the thyrohyoid membrane with the superior laryngeal artery. In basic anatomy textbooks, the external branch is described as passing superficial to the inferior constrictor and piercing it to supply the cricothyroid.Reference Borley, Healey, Collins, Johnson, Crossman, Mahadevan and Standring2 When it contracts, the cricothyroid muscle increases the longitudinal tension of the vocal folds and raises the pitch of the voice. The effects of superior laryngeal nerve injury are subtle and include mild to moderate breathy voice, a reduction in the average vocal pitch and a reduced vocal range.Reference Perry and Gleeson3–Reference Jansson, Tisell, Hagne, Sanner, Stenborg and Svensson4 The severity of the impact of such injury varies according to the voice demands of the individual and is undoubtedly important for professional voice users and singers.

The anatomical course of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, as described by surgical studies, is variable. Various classification systems for the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve have been published, namely the Friedman classification,Reference Friedman, Lo Savio and Ibrahim5 the Cernea classificationReference Cernea, Nishio and Hojaji6 and the Kierner classification.Reference Kierner, Aigner and Burian7

Various methods have been suggested to avoid injury to the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, including division of the sternothyroid, division of the thyroid isthmus before superior thyroid artery ligation, individual ligation of superior thyroid artery branches and the use of a nerve stimulator.Reference Lore, Kokocharov, Kaufman, Richmond and Sundquist8–Reference Jonas and Bahr13 The identification rates quoted by different authors using different techniques vary widely, with the nerve not being identified at all in a number of cases.Reference Lore, Kokocharov, Kaufman, Richmond and Sundquist8–Reference Lekacos, Miligos, Tzaedis, Majiatis and Patoulis15

There is a consensus that careful dissection is required in the region of the superior pole.Reference Moran and Castro16 However, there is no universally accepted technique of preserving the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, and no consensus on whether identification of the nerve is required in every case.

This study aimed to determine the anatomical variations of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve in relation to the inferior constrictor muscle, using the Friedman classification. This was done using cadaver dissection in order to propose a rational approach, based on anatomical principles, for the preservation of the nerve in thyroid surgery. Although previous studies have investigated the anatomy of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, the novelty of this study is that it attempted to highlight the definite prevalence of the type 3 anatomic variant of the nerve.

Materials and methods

Twenty-nine human cadavers (i.e. 58 dissections) of both sexes (27 male and 2 female) were dissected in the anatomy department, Army College of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. The ages ranged from 50 to 70 years (mean age, 58 years). The bodies were fixed for anatomical dissection using standard methods (4 per cent phenolic acid and 0.5 per cent formaldehyde).

Only human cadavers with normal necks were included in the study. The anterior triangles of the neck were dissected and the location of variants of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve was identified according to the Friedman classification. In two hemilarynges, the type of the nerve could not be determined during the dissection; these nerves were probably destroyed during preparation.

Results

In the dissected cadavers, three variants of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve were identified, as per the Friedman classification. These were: type 1, wherein the nerve runs superficial to the inferior constrictor muscle (Figure 1); type 2, wherein the nerve penetrates the lower part of the inferior constrictor muscle (Figure 2); and type 3, wherein the nerve runs deep to the inferior constrictor muscle (Figure 3).

Fig. 1 Photograph of cadaveric dissection showing type 1 Friedman variant: the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve runs superficial to the inferior constrictor muscle (left side). 1 = superior pole of thyroid; 2 = inferior constrictor muscle of pharynx; 3 = external branch of superior laryngeal nerve

Fig. 2 Photograph of cadaveric dissection showing type 2 Friedman variant: the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve runs partly under the cover of the inferior constrictor muscle (right side). 1 = superior pole of thyroid; 2 = inferior constrictor muscle of pharynx; 3 = external branch of superior laryngeal nerve

Fig. 3 Photograph of cadaveric dissection showing type 3 Friedman variant: the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve runs completely under the cover of the inferior constrictor muscle (right side). 1 = superior pole of thyroid; 2 = inferior constrictor muscle of pharynx; 3 = external branch of superior laryngeal nerve

Type 1 variation was found in 57.1 per cent of cases, type 2 in 26.8 per cent and type 3 in 16 per cent. In other words, the type 3 variant was the least common finding. In 17 cadavers there was a difference in the type of variant on the left and right side, as shown in Table I. In two hemilarynges the nerve could not be identified.

Table I Cadavers with nonsymmetrical friedman types*

* For external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. No = number

Discussion

The external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve innervates the cricothyroid muscle, which tenses the vocal fold.Reference Arnold17 The voice symptoms associated with injury to the nerve are easy fatigue during phonation and difficulties with high pitch and singing voice; these symptoms are likely to have serious consequences for a professional voice user.Reference Hong and Kim18 However, no uniform consensus exists regarding the identification of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. A cardinal principle of any surgery is the identification of anatomical structures in order to preserve them. This certainly applies to the identification of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. However, surgeons often express sentiments along the lines of, ‘the superior laryngeal nerve – I know where it should be and I avoid it, but I have never seen it’.

This lack of uniformity regarding the surgical protocol for the identification of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve probably stems from the fact that it has a variable anatomical course. The course of the nerve has been described by many authors, and various classification systems have been defined.

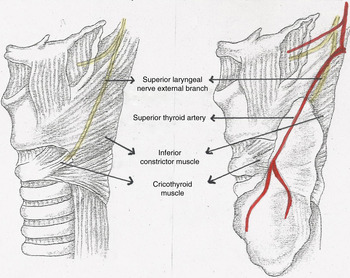

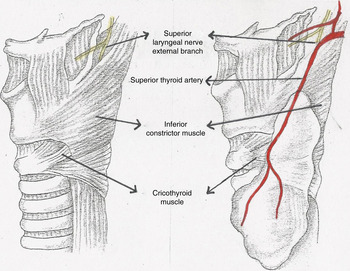

As mentioned in the Results section above, Friedman et al. Reference Friedman, Lo Savio and Ibrahim5 describes three variants of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. In type 1, the nerve runs superficial to the inferior constrictor muscle (Figure 4). In type 2, the nerve penetrates the lower part of the inferior constrictor muscle (Figure 5). In type 3, the nerve runs deep to the inferior constrictor muscle (Figure 6). The type 3 variant may account for the fact that many authors state that the nerve could not be identified during dissection in the region of the upper pole, during thyroid surgery.

Fig. 4 Anatomical diagram showing type 1 Friedman variant: the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve runs superficial to the inferior constrictor muscle.

Fig. 5 Anatomical diagram showing type 2 Friedman variant: the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve runs partly under the cover of the inferior constrictor muscle.

Fig. 6 Anatomical diagram showing type 3 Friedman variant: the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve runs deep to the inferior constrictor muscle.

Cernea et al. Reference Cernea, Nishio and Hojaji6 classify the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve depending on where it crosses the superior thyroid artery in relation to the upper pole of the thyroid gland. According to their system, type 1 nerves cross the superior thyroid artery more than 1 cm above the upper pole, type 2a nerves cross the superior thyroid artery less than 1 cm above the upper pole, and type 2b nerves cross the superior thyroid artery under the cover of the upper pole.

Kierner et al. Reference Kierner, Aigner and Burian7 too classify the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve depending on where it crosses the superior thyroid artery in relation to the upper pole of the thyroid gland. Specifically, type 1 nerves cross the superior thyroid artery more than 1 cm above the upper pole, type 2 nerves cross the superior thyroid artery under the cover of the upper pole, type 3 nerves cross the superior thyroid artery less than 1 cm above the upper pole, and type 4 nerves descend dorsally to the artery and cross the superior thyroid artery branches immediately above the upper pole.

In terms of identification of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve during surgery, we feel that the Friedman classification is more relevant as it directly addresses the issue of the feasibility of such identification. Obviously, a type 3 variation is unlikely to be identified during surgery as it would not be encountered in the field of surgical discussion in a standard thyroidectomy.

• The external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve supplies the cricothyroid muscle, a vocal fold tensor

• Damage to the nerve is detrimental, especially for professional voice users

• The nerve has a variable anatomical course, variously classified

• There is no consensus as to whether its identification should form an essential step in thyroid surgery

• The prevalence of the type 3 Friedman variant of the nerve means that identification is not always possible

• Extracapsular dissection with ligation of superior thyroid vessel branches is recommended

We found a type 3 Friedman variant in 16 per cent of dissections. Our results are consistent with those of Lenquist et al.,Reference Lennquist, Cahlin and Smeds19 who found the nerve to be buried in the fibres of the inferior constrictor in 20 per cent of cases; they inspected the distal part of the inferior constrictor but no muscle dissection was done. Our cadaveric dissection allowed us to identify the Friedman type 3 variant. However, the dissection of the inferior constrictor fibres would not be justified in patients undergoing thyroid surgery.

The surgical technique of extracapsular dissection is widely accepted as being effective in preserving the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve.Reference Shah, Patel and Shah20 Using this technique, only structures which enter the thyroid gland, including individual branches of the superior thyroid artery, are divided. However, as the nerve is closely related to the superior pole, positive identification of the nerve during surgery boosts the confidence of, and reassures, the surgeon. Nevertheless, as our study shows, in a proportion of cases such identification would not be possible. Therefore, the surgeon should keep in mind that even as the nerve is preserved, positive identification may not be achieved.

Conclusion

The external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve lies completely under the cover of the inferior constrictor muscle in a certain percentage of the population. Meticulous, precise dissection in the region of the upper pole of the thyroid gland facilitates identification and preservation of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve in thyroid surgery. However, the surgeon should keep in mind that in a number of cases the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve may not be identifiable, but may still be preserved due to the fact that its course runs deep to the inferior constrictor muscle.