Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the internal auditory meatus and/or the brain is a common structural imaging modality used across many specialties, such as neurology, neurosurgery and ENT surgery; its ability to detect and differentiate brain pathology is superior to that of computed tomography. However, the rate of incidental findings is 2.7–29 per cent.Reference Morris, Whiteley, Longstreth, Weber, Lee and Tsushima1–Reference Amiraraghi, Lim, Locke, Crowther and Kontorinis3

One of the commonest incidental findings is white matter hyperintensity, with a prevalence ranging from 11–21 per cent at the age of 64 yearsReference Ylikoski, Erkinjuntti, Raininko, Sarna, Sulkava and Tilvis4 to 64–94 per cent at the age of 82 years.Reference Garde, Mortensen, Krabbe, Rostrup and Larsson5 White matter hyperintensity usually refers to hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted sequences, which can appear as isointense or hypointense on T1-weighted imaging. These lesions tend to be located peri-ventricularly or in deep white matter, and are often associated with small vessel disease, which refers to a cerebral ischaemic condition that mainly affects small cerebral subcortical arteries.Reference Berry, Sidik, Pereira, Ford, Touyz and Kaski6

The occurrence of white matter hyperintensity increases with age. Other known associated factors are Afro-Caribbean ethnicity, hypertension, diabetes and high cholesterol levels.Reference Grueter and Schulz7 There may also be a genetic component to the development of white matter hyperintensities.Reference Sachdev, Thalamuthu, Mather, Ames, Wright and Wen8 Not all white matter hyperintensities are of vascular origin; they can be seen in other neurological conditions such as migraine, demyelination or inflammatory processes. ‘True’ small vessel disease is associated with cognitive decline, depression, gait disturbance, falls and increased risk of stroke.Reference Debette and Markus9 Despite the available evidence on white matter hyperintensities with presumed vascular origin and small vessel disease, the clinical management of patients with white matter hyperintensity detected as an incidental finding is unclear.

Our main objective was to determine the clinical significance and relevance of white matter hyperintensity as an incidental radiological finding. We identified patients with incidental white matter hyperintensity on their initial imaging report, investigated the development of stroke, transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or myocardial infarction in a five-year follow-up period, and explored factors that could predict the likelihood of a cerebral or cardiac event.

Methods

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the British national and local institutional guidelines on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Ethical approval was granted by the local hospital ethical review board.

Basic settings and patient selection

We carried out an observational retrospective study in a tertiary referral university setting. We reviewed the reports of 6978 consecutive MRI scans of the internal auditory meatus in adults (older than 16 years). These were requested because of unilateral or asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss or unilateral tinnitus, to rule out a vestibular schwannoma (retrocochlear pathology). All scans were conducted between 2013 and 2015, in an ENT department with a catchment area of 1.2 million for secondary referrals and 2.2 million for tertiary referrals.

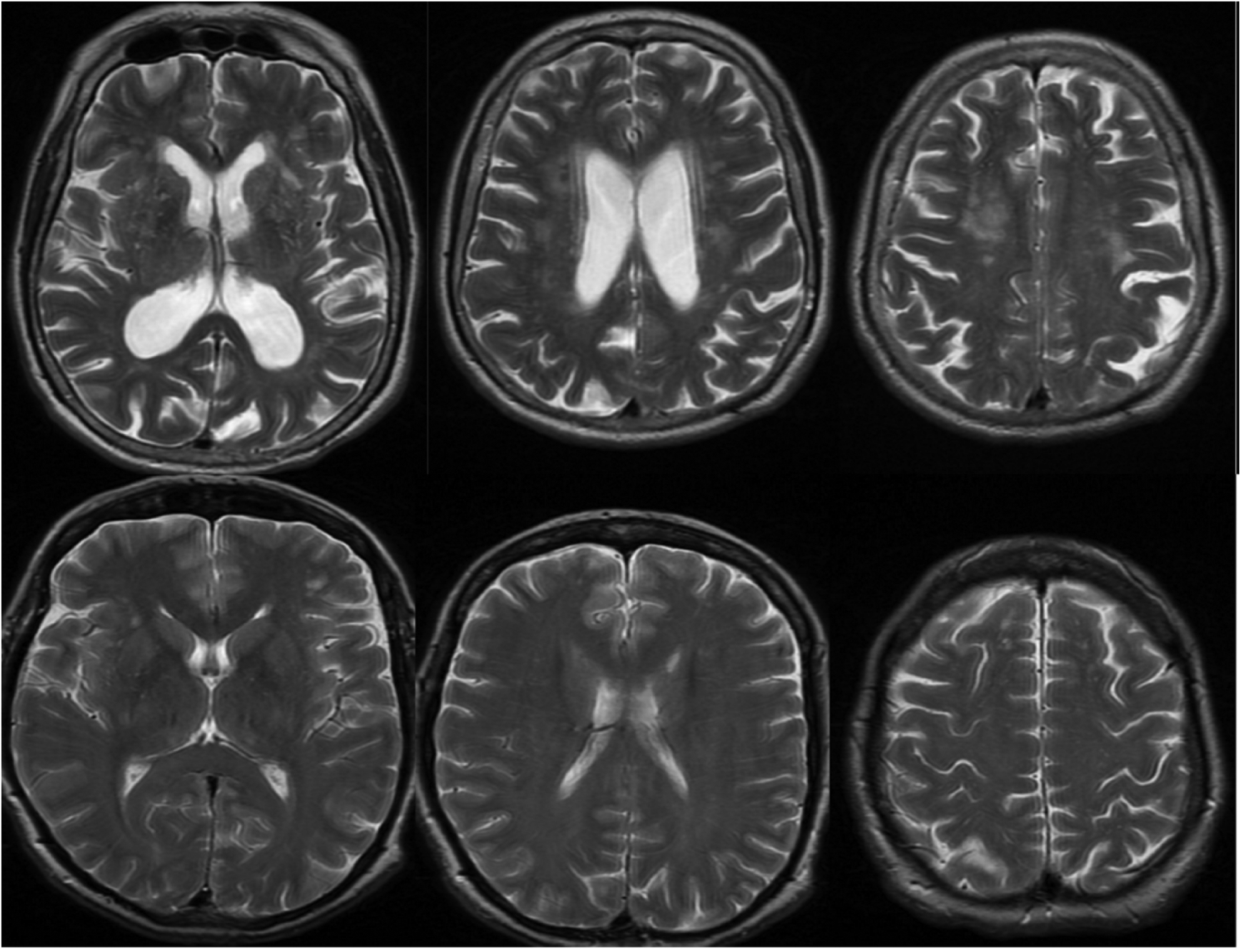

We identified those patients stated to have white matter hyperintensities on MRI on the radiology report (Figure 1), and reviewed their clinical electronic notes at the time of the initial referral or imaging. Terms such as white matter hyperintensities, small vessel disease, white matter disease, white matter changes and small vessel ischaemia were all considered white matter hyperintensities. Patients with a tumour or other significant pathology were excluded. Patients were included if white matter hyperintensities were the only significant finding on the scan.

Fig. 1. Examples of axial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans from our cohort. Top panel: T2-weighted MRI scans of the brain with confluent white matter changes suggestive of small vessel disease. Bottom panel: T2-weighted MRI scans of the brain with scattered punctate white matter hyperintensities that are non-specific, rather than of vascular origin.

Imaging parameters

The MRI studies were performed using a 1.5 Tesla system without intravenous gadolinium administration, with reconstruction on axial, coronal and sagittal plane, including a T1-weighted sequence and a balanced steady-state gradient echo sequence (mostly fast imaging employing steady-state acquisition (‘FIESTA’) or three-dimensional constructive interference in steady state (‘CISS’) sequences). Although the studies were performed in different scanners within the hospital, the above-named sequences were used as a standardised screening protocol. Additional T1-weighted scans with gadolinium were acquired in cases of abnormal findings that required further characterisation.

Included factors

For all the patients identified with white matter hyperintensities on MRI, we collected information including age, sex and cardiovascular risk factors at the time of initial referral. The risk factors assessed included: arterial hypertension, diabetes, smoking, hypercholesterolaemia, ischaemic heart disease, previous stroke or TIA, congestive cardiac failure, and atrial fibrillation

Five years later, we revisited the patients’ notes and recorded the same factors for each patient. We additionally documented whether a patient had had a vascular event, namely myocardial infarction, new TIA or stroke, within this five-year period. Finally, we also documented any deaths, as well as their cause, for the same period.

We did not record the presence of family history and body mass index because of poor documentation of such factors in the medical notes.

Data analysis

Data were recorded on Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft™). Parametric data were compared using independent t-tests and chi-square tests, to examine differences between the group that had cerebral or cardiac events and the group that did not have any such events. Non-parametric data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. All statistical tests were carried out using IBM® SPSS® Statistics, version 24.

Finally, a binary logistic model was used to identify risk factors independently associated with cerebral or cardiac events. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Of 6978 MRI scans performed within the three-year period, 309 patients (4.4 per cent) were found to have white matter hyperintensities and were included in the present study. Follow-up data were available for all patients.

The patient cohort that developed vascular events (stroke or myocardial infarction) within five years of imaging had a significantly higher number of vascular risk factors than the group that did not have any events in this five-year period (stroke or TIA, p = 0.003; myocardial infarction, p = 0.025).

In particular, compared with patients who had not had a stroke or TIA at the end of five years, the group who suffered from stroke or TIA had a statistically significantly higher proportion of patients with hypercholesterolaemia (p = 0.009) and previous history of stroke or TIA (p = 0.002). The patients’ basic demographics, comparing the group who had a stroke or TIA, or myocardial infarction, with those who did not have these events, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Patients’ demographics

*Indicates significant difference. TIA = transient ischaemic attack; SD = standard deviation; IQR = interquartile range

Overall, during the follow-up period, 20 patients (6.5 per cent) had stroke or TIA, and 5 (1.7 per cent) had myocardial infarction. Two patients (0.7 per cent) had both a stroke and a myocardial infarction, but no other patients had multiple vascular events. Forty-two patients (13.6 per cent) died. The cause of death was unknown for 11 patients. Two patients (0.7 per cent) died of cardiac arrest secondary to acute myocardial infarction. Only one patient (0.2 per cent) died of stroke, which was a recurrent embolic stroke secondary to non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis.

In binary logistic regression models adjusted for age and sex, the number of vascular risk factors was significantly associated with both vascular outcomes: stroke or TIA (p = 0.004, odds ratio = 1.6 (95 per cent confidence interval (CI) = 1.2–2.3)), and myocardial infarction (p = 0.023, odds ratio = 2.1 (95 per cent CI = 1.1–4.1)) (Figure 2). In a multiple regression model, where all individual risk factors were included, hypercholesterolaemia (p = 0.016, odds ratio = 4.2 (95 per cent CI = 1.3–13.6)) and previous history of stroke or TIA (p = 0.012, odds ratio = 4 (95 per cent CI = 1.4–1.9)) were still significantly associated with stroke and TIA events at follow up. No risk factors were significantly associated with myocardial infarction.

Fig. 2. A probability graph indicating the number of vascular risk factors and the likelihood of a vascular event in patients with white matter hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging. In our model, patients with three vascular risk factors had about a 10 per cent higher risk of developing a future vascular event in five years compared with those who did not have any vascular risk factors. This likelihood is rising further with the addition of more risk factors CI = confidence interval

Discussion

Main findings

Over a five-year observational period, we found that the number of vascular risk factors was significantly associated with the risk of further cardiac or cerebral vascular events in patients with incidental findings of white matter hyperintensities on MRI of the internal auditory meatus. In terms of individual risk factors, there were significantly more patients with high cholesterol levels, or previous stroke or TIA, experiencing a stroke or TIA within five years. None of the individual risk factors was significantly correlated with the outcome of myocardial infarction, probably because of the low event rate.

Overall, we identified an increased number of vascular risk factors (three or more) or history of a previous vascular event as a prognostic factor for a vascular event within five years in patients with incidental white matter hyperintensities on MRI. Incidental white matter hyperintensities should be carefully investigated, and if they are considered to be of vascular origin (i.e. more than would be expected given the patient's age, with other neurological causes ruled out, and in patients with significant vascular risk factors), then measures should be taken to ensure that the vascular risk factors which can be controlled are optimally managed.

White matter hyperintensities and stroke

White matter hyperintensities are not an uncommon incidental finding on MRI of the brain and internal auditory meatus. Pathophysiologically, the cause is not well understood and could be multifactorial.Reference Gouw, Seewann, van der Flier, Barkhof, Rozemuller and Scheltens10 They may be the result of chronic ischaemia, or toxic substances leaking into the brain because of the breakdown of the blood–brain barrier, or the combination of both.Reference Fazekas, Kleinert, Offenbacher, Schmidt, Kleinert and Payer11–Reference Pantoni and Garcia14 They are more commonly found in patients with cardiovascular risk factors, or in those who have had previous cardiac or cerebral vascular events. In patients with confirmed small vessel disease, white matter hyperintensities are independently associated with the risk of future stroke events (hazard ratio = 3.5) and an increased risk of death (hazard ratio = 2).Reference Debette and Markus9

In our study, 6.5 per cent of patients who had white matter hyperintensities had a stroke or TIA, and only 2 per cent had a myocardial infarction, within the next five years; this rate is lower than that reported in small vessel disease studies (9.8–16 per cent).Reference Staszewski, Piusinska-Macoch, Brodacki, Skrobowska, Macek and Stepien15–Reference Poels, Steyerberg, Wieberdink, Hofman, Koudstaal and Ikram17 However, in those studies, the patients included had at least white matter hyperintensities and lacunar infarcts, rather than white matter hyperintensities alone. The patient population was a defined group with a confirmed diagnosis of small vessel disease, and not white matter hyperintensities as an incidental finding.

Other imaging characteristics of small vessel disease include cerebral microbleeds, cerebral superficial siderosis, brain atrophy and enlarged perivascular spaces. Increasingly, studies have used a combined small vessel disease score to predict the risk factors and outcomes, which incorporates all small vessel disease imaging features and the severity of the changes.Reference Staals, Makin, Doubal, Dennis and Wardlaw18,Reference Pinter, Ritchie, Doubal, Gattringer, Morris and Bastin19 Therefore, it is not unexpected that the stroke risk was higher in these groups than in our group, who had white matter hyperintensities from imaging only with undefined characteristics.

Previous studies have shown age to be a risk factor for stroke.Reference Kelly-Hayes20 However, age was not significantly associated with the occurrence of stroke in our study. This is not related to any discrepancies, but to our study's setup and objective; we did not look into generic risk factors for stroke, but into the significance of white matter hyperintensities as a warning imaging finding for future vascular events and how the generic known risk factors affect this specific group of patients. It appears that the number of vascular risk factors has a much more significant association with stroke than has age in patients who present with a radiological finding of white matter hyperintensities. Our group is also older than the groups included in previous studies that investigated purely the impact of risk factors in the generic adult population (typically aged over 16 years old, compared with a range of 53–80 years included in the present study). Moreover, we observed our cohort for 5 years; if we observe the patients for a longer period (10 years), we expect there will be higher rates of stroke or myocardial infarction, and possibly an association with age.

Similarly, in our study, hyperlipidaemia was shown to be significantly associated with further stroke risk; the same did not apply for other major risk factors, such as hypertension. In our study, we defined hyperlipidaemia as any patients who were on statin. However, our patient group is a heterogeneous group. Patients who were on statin were more likely to have other vascular risk factors, or previous stroke or ischaemic heart disease.

White matter hyperintensities and small vessel disease

Although white matter hyperintensities are often thought to be associated with small vessel disease, they can also be related to other underlying causes, including neuroinflammation, demyelination, infection, or even migraine or the normal ageing process. The findings of magnetic resonance imaging scans of the brain or the internal auditory meatus reported by general radiologists can be misleading, with white matter hyperintensities described as small vessel disease. Furthermore, the extent of white matter changes is often not defined. The cases of true small vessel disease in our study were probably overestimated; therefore, we described the findings as white matter hyperintensities rather than small vessel disease.

A radiological-neuropathological study suggested that T2-weighted MRI, and a fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence, overestimates periventricular and perivascular lesions,Reference Haller, Kövari, Herrmann, Cuvinciuc, Tomm and Zulian21 compared with histopathologically confirmed degeneration of myelin.Reference Kelly-Hayes20 Overall, punctate white matter hyperintensities can have various causes and are unlikely to progress, whereas confluent lesions have a high risk of progression over time.Reference Schmidt, Petrovic, Ropele, Enzinger and Fazekas22 Therefore, it is essential to distinguish age-related white matter hyperintensities from small vessel ischaemia in clinical practice, which can prevent unnecessary anxiety for the patient and spare health resources that are under increasing pressure.

Clinical implications of incidental white matter hyperintensities

The optimal management of incidental white matter hyperintensities in clinical practice is controversial. It is essential to assess the distribution and severity of the white matter changes, to identify cardiovascular risk factors and neurological symptoms, and to treat the risk factors appropriately.

As per our findings, in patients with incidental white matter hyperintensities on MRI who have had a previous stroke, hypercholesterolaemia and/or the presence of three or more vascular risk factors, the risk of a vascular event in a five-year period is significantly increased; thus, each vascular risk factor should be addressed, and close attention should be paid to those with hypercholesterolaemia. With respect to the patients without any known risk factors, we should review their cases and make sure that there are definitely none.

Finally, although preventive medication was not the aim of our study, it is worth mentioning that while one could suggest routine use of antiplatelet medication in certain patients with white matter hyperintensities on MRI and co-existing risk factors, the current evidence does not support using antiplatelets as a primary prevention for stroke.Reference Gelbenegger, Postula, Pecen, Halvorsen, Lesiak and Schoergenhofer23,Reference Judge, Ruttledge, Murphy, Loughlin, Gorey and Costello24

Strengths and limitations

Despite the observational character of our study, it has a number of limitations. The study cohort consisted of patients who had an incidental finding of white matter hyperintensity on MRI scans of the brain and internal auditory meatus, rather than confirmed small vessel disease. It is probable that a small proportion of the patients included did not have small vessel disease, which could have affected, to a minor extent, the application of our findings.

• The risk of vascular events in patients with an incidental finding of white matter hyperintensity is unclear

• Not all white matter hyperintensities are of vascular origin

• The number of vascular risk factors predicts further risk

• Patients with a history of hypercholesterolaemia, stroke or transient ischaemic attack are at higher risk

• In patients with incidental white matter hyperintensities, vascular risk factors should be identified and addressed appropriately

Additionally, the information on the radiological appearance of the white matter hyperintensities was taken from radiological reports that did not necessarily include a description of the severity and the extent of the findings. We could not include imaging parameters in our study, although it is known that the baseline severity of white matter hyperintensities and lacunar infarcts are independent predictors for future stroke or TIA.Reference van Zagten, Boiten, Kessels and Lodder25–Reference Gouw, van der Flier, Fazekas, van Straaten, Pantoni and Poggesi27

More importantly, this was a cohort study; there was no controlled group with similar vascular risk factors without white matter hyperintensities. Therefore, we could not compare the vascular event rates between these two groups. Thus, we cannot draw the conclusion that patients with incidental white matter hyperintensities and vascular risk factors are more likely to have a stroke compared with those who have similar vascular risk factors but no white matter hyperintensities.

Finally, the outcome data were gathered from electronic case notes, rather than from a clinical follow up. We do not have enough information to assess other outcomes related to small vessel disease, such as cognitive impairment and mobility issues.

Nevertheless, this study aimed to examine the incidental findings, and attempt to inform non-neurologists on what to do with such findings; the setup of our study was tailored to answer this question. The robust, observational design of our study facilitated overcoming bias linked to a retrospective case series. It also allowed us to focus on our main target: dealing with the patient with white matter hyperintensities as an incidental MRI finding and obtaining results that are meaningful in clinical practice.

Conclusion

We demonstrated that the number of co-morbidities is the most relevant factor in the risk of developing future cerebral and cardiovascular events within a five-year period in patients with incidental white matter hyperintensities. Additionally, the presence of previous stroke or TIA and/or high cholesterol levels in these patients is significantly associated with further cerebrovascular events. In patients with incidental white matter hyperintensities, the clinician should ensure that cardiovascular risk factors are assessed and treated as appropriate. A prospective case-controlled study is necessary to investigate this further.

Competing interests

None declared