Introduction

Otosclerosis is a condition characterised by osseous dysplasia affecting bone derived from the embryonic otic capsule, leading to progressive hearing loss. The most commonly involved region is the fissula ante fenestram, anterior to the oval window. Over 90 per cent of cases present with conductive hearing loss due to fixation of the stapes footplate (fenestral otosclerosis). With disease progression, the inner ear may be involved (retrofenestral otosclerosis), resulting in either mixed or sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). Furthermore, the underlying cochlear thresholds may deteriorate because of age-related hearing loss.

There is a lack of effective medical treatment.Reference Hentschel, Huizinga, van der Velden, Wegner, Bittermann and Vander Heijden1 Conventional hearing aids can counter the hearing loss, but patients may find these unsatisfactory or unacceptable. Stapes surgery is the established surgical treatment for otosclerosis. Bone conducting implants are one hearing rehabilitation solution,Reference Burrell, Cooper and Proops2 but traditional percutaneous devices have their associated disadvantages. The transcutaneous solutions available to date have a limited fitting range, and those with active external processors lack power, especially in the high frequencies. When patients present with mixed hearing loss and successful stapes surgery closes the air–bone gap, they can still struggle with functional hearing. A conventional hearing aid is then offered. In far advanced otosclerosis, stapes surgery can be attempted but cochlear implantation may become the only option.Reference Quaranta, Bartoli, Lopriore, Fernandez-Vega, Giagnotti and Quaranta3

In this short communication, we describe a novel solution for rehabilitation of the mixed hearing loss in advanced otosclerosis, and present a case that was successfully rehabilitated with stapedotomy in combination with incus short process vibroplasty (using a Vibrant Soundbridge device; Med-El, Innsbruck, Austria).

Case report

A 50-year-old male with long-standing bilateral progressive mixed hearing loss was referred to St Thomas’ Hearing Implant Centre, as he was no longer able to wear acoustic hearing aids because of recurrent otitis externa and secondary external canal stenosis (Figure 1a). The occlusive effect of the hearing aid moulds was exacerbating these symptoms.

Fig. 1 (a) Patient's right ear canal and (b) incus short process vibroplasty.

The mean air conduction threshold in the worse hearing ear (right side) was 75 dB HL, with a mean air–bone gap of 53 dB HL (for 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz). The diagnosis of otosclerosis was confirmed on high-resolution computed tomography. The mixed moderate-to-severe hearing loss meant that ongoing hearing aid use was likely to be necessary even after successful stapes surgery. Therefore, it was deemed by the multidisciplinary team (MDT) that stapes surgery alone would not provide a solution to the patient's problems. After an auditory implant MDT meeting and discussion of the management options with the patient, a plan was agreed for staged surgical procedures.

The patient underwent incus short process vibroplasty with the Vibrant Soundbridge device (Figure 1b). This was followed six weeks later by stapes surgery using a 4.75 mm × 0.6 mm GYRUS ACMI Smart stapes prosthesis. There were no surgical complications following either procedure. The implant was activated 17 days after stapedotomy.

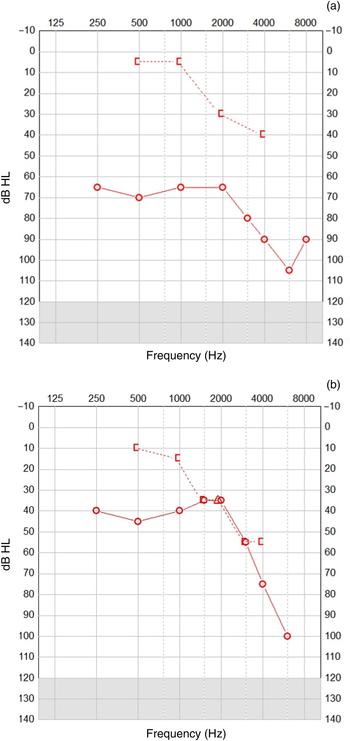

Post-operative pure tone audiometry conducted 17 days after stapes surgery showed a reduction of the mean air–bone gap from 55 dB to 20 dB (Figures 2a and b). The residual mixed hearing loss was rehabilitated with the Vibrant Soundbridge, with a mean device gain of 32 dB across all measured frequencies (Figures 3 and 4). The monosyllabic Arthur Boothroyd word recognition scores in quiet at 65 dB improved from 37 to 100 per cent when using the Vibrant Soundbridge at six months after switch-on of the device. The patient reported significant post-intervention improvement in sound quality and speech intelligibility.

Fig. 2 (a) Pre-operative audiogram and (b) post-stapes surgery audiogram. [ = bone conduction (masked); ○ = air conduction (unmasked)

Fig. 3 Right ear aided and unaided pre-operative (pre-op) and post-operative sound field audiometry with right Vibrant Soundbridge sound processor (left ear blocked).

Fig. 4 Functional gain with the Med-El Samba audio processor for the Vibrant Soundbridge.

Discussion

The Vibrant Soundbridge is a semi-implantable electromagnetic middle-ear device. It consists of an external audio processor and an implanted coil and demodulator, connected to a floating mass transducer via a conductor link. Over the past decade, a number of centres across Europe have published their overall positive experience with the device.Reference Schmuziger, Schimmann, Wengen, Patscheke and Probst4, Reference Mosnier, Sterkers, Boucarra, Labassi, Bebear and Bordure5

In the setting of the traditional indication of mild-to-severe SNHL, the most commonly used technique has been long process incus vibroplasty, in which the floating mass transducer is coupled to the long process of the incus through a posterior tympanotomy. More recently, however, a range of new or updated couplers have been introduced, thereby significantly increasing the options for attaching the floating mass transducer to the most appropriate middle-ear structure with improved surgical efficiency.

Preliminary studies have shown the attachment of a floating mass transducer on the short process of the incus to provide promising results.Reference Schraven, Dalhoff, Wildenstein, Hagen, Gummer and Mlynski6, Reference Mlynski, Dalhoff, Heyd, Wildenstein, Rak and Radeloff7 In our case, short process coupling enabled incus vibroplasty without compromising optimal placement of the stapes prosthesis on the long process.

Use of the traditional long process coupler that required manual crimping in combination with a Teflon piston was first described for advanced otosclerosis in 2007.Reference Dumon8 A single-stage procedure using a combined approach with stapedotomy and interposition vein graft was described. The Teflon piston was fitted over the clip for the floating mass transducer. The short process coupler negates the need for this more complicated arrangement.

Our vibroplasty and stapedotomy were carried out in two stages, six weeks apart. Our rationale for undertaking the vibroplasty first was based on the potential risk of SNHL due to excessive movement of the stapes prosthesis during floating mass transducer coupling to the incus. The implications of an unsuccessful stapedotomy following vibroplasty were also considered. Another potentially feasible option would be to perform vibroplasty first followed by stapes surgery (as in this case), but in a single operation.

Kontorinis et al. have carried out single-stage combined approach surgery with long process vibroplasty before insertion or attachment of the stapes prosthesis.Reference Kontorinis, Lenarz, Mojallal, Hinze and Schwab9 They discussed the increased risk of ossicular disruption due to enhanced mobility of the ossicular chain after stapedectomy. They encountered problems with excessive bleeding during the stapedotomy in two out of three cases, but were able to successfully complete the procedures.

Currently, we have not attempted these procedures in a single stage because of the risk of blood from the mastoidectomy compromising the success of the stapes surgery. With more experience and confidence, this approach may be considered in future.

In the case presented, we believe some of the conductive component of the hearing loss was attributable to chronic inflammation and stenosis of the ear canal, possibly accounting for incomplete closure of the air–bone gap after stapes surgery.

Commissioning guidelines in the UK mean that we can only offer this intervention to patients who are unable to wear conventional hearing aids. However, some patients may find the Vibrant Soundbridge in combination with stapes surgery a more satisfactory solution to their hearing loss than a conventional hearing aid after stapes surgery. We advocate an MDT approach and candid discussion with suitable patients to enable staged surgical management with incus vibroplasty as the first operation.

Conclusion

Stapedotomy in conjunction with short process incus vibroplasty is a safe and promising option for patients with advanced otosclerosis and mixed hearing loss.

Acknowledgement

Mr Terry Nunn – consultant clinical scientist (audiology) and head of audiology.