Introduction

Fibromyalgia syndrome is an intractable, widespread pain disorder that is most frequently diagnosed in women. It does not have a distinct cause or pathology. It is a common yet poorly understood syndrome characterised by diffuse, chronic pain accompanied by other somatic symptoms, including poor sleep, fatigue and stiffness, in the absence of disease. The patients with fibromyalgia syndrome experience pain differently from the general population, because of dysfunctional pain processing in the central nervous system.

In fibromyalgia syndrome, aberrant pain processing, which can result in chronic pain and associated symptoms, may be the result of several interconnected mechanisms, including central sensitisation, blunting of inhibitory pain pathways, alterations in neurotransmitters, and comorbid psychiatric illness.Reference Abeles, Pillinger and Solitar1 The pathogenesis of the otoneurological and systemic manifestations of the disease may be due to neural disintegration, or to some other event related to neural mediators. Such a neural process may possibly lead to abnormal perception of stimuli from the internal or external environments.Reference Bayazit, Gursoy, Ozer, Karakurum and Madenci2

The fibromyalgia syndrome is associated with a number of conditions, such as sleep disturbance, fatigue, depression, spastic colon, mitral valve prolapse, bursitis, chondromalacia, constipation, diarrhoea, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, vertigo, sinus and thyroid problems, concentration problems, sensory symptoms, swollen glands, tinnitus, chronic cough, coccygeal and pelvic pain, tachycardia, and weakness. Almost 70 per cent of patients reported that their symptoms were aggravated by noise, lights, stress, posture and weather.Reference Waylonis, Heck and Fibromyalgia3 Almost 70 per cent of patients may have a decreased, painful sound threshold.Reference Gerster and Hadj-Djilani4 However, no acoustic reflex arc abnormality has been reported.Reference Bayazit, Gursoy, Ozer, Karakurum and Madenci2

Central nervous system abnormalities have been reported in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Decreased thalamic blood flow has been noted by several investigators.Reference Cook, Stegner and McLoughlin5 Single-photon-emission computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging assessments of the brain have shown reduced cerebral blood flow in the pons.Reference Kwiatek, Barnden, Tedman, Jarrett, Chew and Rowe6 Patients with fibromyalgia syndrome may have significantly less total grey matter volume and a 3.3 times greater age-associated decrease in grey matter, compared with healthy controls.Reference Kuchinad, Schweinhardt, Seminowicz, Wood, Chizh and Bushnell7

Neural mediators function in the transmission of stimuli in neuronal synapses. It has been postulated that disturbances in serotonin metabolism and transmission, along with disturbances in several other chemical pain mediators, are present in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome.Reference Alnigenis and Barland8 Auditory evoked potentials have been related to weak serotonergic transmission, and deficient inhibition of the response to noxious and intense auditory stimuli may be due to a serotonergic deficit in fibromyalgia syndrome patients.Reference Carrillo-de-la-Pena, Vallet, Perez and Gomez-Perretta9

Measurement of otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) has been an important clinical and diagnostic tool since it was first described by Kemp in 1978. By means of OAEs, it is possible to objectively monitor minute changes in cochlear status which would be undetectable by other audiological methods. The OAEs are produced by active micromechanisms of the outer hair cells of the organ of Corti.

Transiently evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAEs) are sounds emitted in response to an acoustic stimuli of very short duration – most commonly clicks, but tone-bursts have also been used. When present, TEOAEs generally occur at frequencies of 500 to 4000 Hz. Transiently evoked otoacoustic emissions can be recorded in almost any subject with normal hearing. Distortion product OAEs are sounds emitted in response to two simultaneous, pure tones at two different frequencies (i.e. f1 and f2, where f2 > f1) and two different intensity levels (i.e. L1 and L2). The relationship between L1–L2 and f1–f2 dictates the frequency response. An f1/f2 ratio yields the greatest distortion product OAEs, at 1.2 for low and high frequencies and at 1.3 for medium frequencies. To yield an optimal response, intensities should be set so that L1 equals or exceeds L2. Lowering the absolute intensity of the stimulus renders the distortion product OAEs more sensitive to abnormality. Distortion product OAEs frequently correspond to the audiometric configuration of a cochlear hearing loss.

Suppression of OAEs is mediated by efferent fibres originating in the superior olivary complex in the brain stem. The axons of the lateral and medial olivocochlear bundles extend dorsomedially from the superior olivary complex, pass through the reticular formation, combine into a bundle close to the floor of the fourth ventricle, leave the brain stem as a ventral component of the inferior vestibular nerve, and then join to the cochlear nerve as Oort's vestibulocochlear anastomosis at the base of the modiolus. The axons of the lateral olivocochlear bundles synapse with the afferent (type I) neurons that originate from the inner hair cells in the organ of Corti. Axons of the medial olivocochlear bundles enter the organ of Corti and terminate at the base of the cell bodies of the outer hair cells.

The majority of the medial efferents project or cross back to the ear of stimulus origin. It is believed that medial efferents induce hyperpolarisation which counteracts the contractile (amplifying) effects of outer hair cell activity. Medial efferent stimulation reduces the gain that would result from outer hair cell activity.Reference Velenovsky, Glattke, Robinette and Glattke10 Since a contralateral, sound-induced suppressive effect is mediated by medial superior olivary complex neurons, contralateral suppression of TEOAEs can be used as a non-invasive and direct index of medial superior olivary complex efferent activation. Contralateral suppression of OAEs refers to a reduction in OAE amplitude on stimulation of the contralateral ear. This effect is attributed to alteration of cochlear micromechanics by the medial superior olivary complex.Reference Maison, Micheyl and Collet11

Suppression of OAEs could be useful in the diagnosis of pontine lesions, such as acoustic neuromas, meningiomas, congenital cholesteatomas, multiple sclerosis, ischaemic infarcts and tumours.Reference Prasher, Ryan and Luxon12

Contralateral suppression of OAEs has not been studied in fibromyalgia syndrome to date. In this study, we aimed to assess brain stem neural integrators indirectly by using contralateral suppression of TEOAEs in the patients with fibromyalgia syndrome who had normal hearing.

Materials and methods

Twenty-four female patients with fibromyalgia syndrome (age range 23 to 58 years, mean age 34.4 years) and 24 healthy female controls (age range 23 to 59 years, mean age 34.9 years) were included in the study. Forty-eight ears of the patients and controls were audiologically tested. Clinical history, blood tests and physical examination established that none of the patients or controls had any chronic otological diseases, ototoxicity, previous ear surgery, central nervous system disease, or any systemic, metabolic or autoimmune disease that could affect ear function.

The diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome was made on the basis of the American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria.Reference Wolfe, Smythe, Yunus, Bennett, Bombardier and Goldenberg13 Briefly, these criteria comprise diffuse aches and stiffness in the muscle and tendon insertions on digital palpation with an approximate force of 4 kg (the amount of pressure required to blanch a thumbnail), lasting for at least three months. To meet the diagnostic criteria, pain must be present in 11 or more of the 18 specified tender point sites. The fibromyalgia questionnaire was applied to all patients.Reference Burckhardt, Clark and Bennett14 The patients had no symptoms other than pain. We excluded from the study any patient with objective signs of articular or periarticular disease, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of more than 10 mm/h, positive latex fixation test, elevated creatine phosphokinase values, or obvious underlying disease such as diabetes mellitus, chronic renal insufficiency, epilepsy, chronic psychiatric disorder, multiple sclerosis or hypothyroidism.

Audiological evaluation

Pure tone audiometry and acoustic impedance testing was performed in the patients and controls. Pure tone averages (PTAs) were calculated at 500, 1000, 2000 and 3000 Hz.

The transiently evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAEs) were recorded by means of an ILO-88 cochlear emission analyser (Otodynamics, London, UK), using insert ear phones in a sound-attenuated room. The TEOAEs were obtained from 1 to 4 kHz, with stimuli consisting of clicks of 80 µs duration. The stimulus level in the outer ear was set at 83 ± 3 dB SPL. The click rate was 50 per second, and post-stimulus analysis was in the range of 2 to 20 ms. A total of 260 sweeps was averaged above the noise rejection level of 47 dB. The stimuli were presented in the nonlinear mode, in which every fourth click stimulus was inverted and three times greater in amplitude than the three preceding clicks. A TEOAE was defined as a response if its amplitude was ≥3 dB above the level of the noise floor. Reproducibility percentages of ≥70 per cent and stimulus stability of ≥80 per cent were taken into account as acceptable for analysis. For contralateral suppression of TEOAEs, insert ear phones (Otodynamics ILO 292 DP Echoport Plus, England) (Ear tone 3A 10 Ohm 410-3010) were used in the contralateral ear, in which a 40 dB, white noise sensation level was given to obtain the optimal measurement parameters.Reference De Ceulaer, Yperman, Daemers, Van Driessche, Somers and Offeciers15 Five successive measurements were performed in the frequency range 1–4 kHz, and the mean values of the amplitudes obtained with these successive measurements were used in the comparisons.

Statistics

The paired t-test was used to compare the TEOAE amplitudes obtained with and without contralateral suppression. Independent samples t-testing was used to compare the parameters of the patients and controls.

Results

There was no significant difference between the ages and genders of the patients and controls (p > 0.05). All patients with fibromyalgia syndrome and all healthy controls had normal hearing on pure tone audiometry. The mean PTA values were 9.1 ± 5 dB (range 3–32 dB) in controls and 9.3 ± 6 dB (range 5–21 dB) in patients. The PTAs of the patients and controls were not significantly different (p > 0.05).

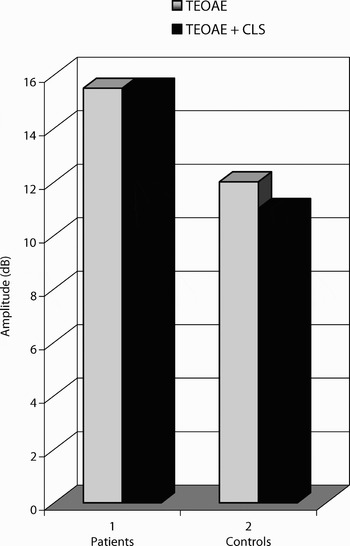

In fibromyalgia syndrome patients, the mean transiently evoked otoacoustic emission (TEOAE) amplitude was 15.5 ± 4.8 dB. The mean TEOAE amplitude after contralateral suppression was 15.5 ± 4.9 dB. There was no statistically significant difference between the TEOAE amplitudes measured before and after contralateral suppression (t = 0.68; 47 degrees of freedom; p = 0.948).

In the controls, the mean TEOAE amplitude was 12 ± 5 dB. The mean TEOAE amplitude after contralateral suppression was 11 ± 4.7 dB. There was a statistically significant difference between the TEOAE amplitudes measured before and after contralateral suppression (t = 4.149; 47 degrees of freedom; p < 0.01). The amplitudes of emissions decreased after contralateral suppression.

The TEOAE amplitudes obtained before and after contralateral suppression were greater in fibromyalgia syndrome patients (t = 3.486; 94 degrees of freedom; p = 0.01) than controls (t = 4.552; 94 degrees of freedom; p < 0.01) (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 Transiently evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAEs) of fibromyalgia syndrome patients and controls, obtained with and without contralateral suppression (CLS).

Discussion

Although fibromyalgia syndrome patients generally have subjective ear-related symptoms, clinical and laboratory assessments usually fail to detect any objective abnormality. Otological functions, and OAEs, seem to be spared in fibromyalgia syndrome.Reference Yilmaz, Baysal, Gunduz, Aksu, Ensari and Meray16 However, our study showed abnormal contralateral suppression of transiently evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAEs) in fibromyalgia syndrome patients. In our study, although TEOAEs could be obtained in all fibromyalgia syndrome patients and controls, the amplitudes of emissions were significantly lower in patients than controls. In addition, contralateral suppression of TEOAEs existed in healthy controls – a normal physiological finding. However, contralateral suppression of TEOAEs was absent in the fibromyalgia syndrome patients – an abnormal finding.

Contralateral suppression of OAEs means decreased OAE amplitudes in response to a sound stimulus in the contralateral ear. This physiological mechanism functions via a brain stem neural network connecting both ears. In this network, the medial superior olivary complex fibres synapse on outer hair cells, and activation of these fibres inhibits basilar membrane responses to low-level sounds. This medial superior olivary complex induced decrease in the gain of the cochlear amplifier is reflected in changes in the OAEs. The most straightforward technique for monitoring medial superior olivary complex effects is to elicit medial superior olivary complex activity with an elicitor sound contralateral to the OAE test ear.Reference Guinan17 Therefore, absence of contralateral suppression of OAEs in fibromyalgia syndrome indicates an abnormal function of the medial superior olivary complex itself or of the synapses of medial superior olivary complex fibres with outer hair cells.

• Fibromyalgia syndrome is an intractable, widespread pain disorder that is most frequently diagnosed in women. It does not have a distinct cause or pathology

• In fibromyalgia syndrome, aberrant pain processing, which can result in chronic pain and associated symptoms, may be the result of several interconnected mechanisms

• This study aimed to assess brain stem neural integrators indirectly by using contralateral suppression of transiently evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAEs) in fibromyalgia syndrome patients with normal hearing

• Mechanisms related to contralateral suppression of TEOAEs seem dysfunctional in fibromyalgia syndrome

• Demonstration of a lack of contralateral suppression of TEOAEs can be used as a diagnostic tool in fibromyalgia syndrome patients

On auditory brain stem response testing, significant differences were reported for the I–V and III–V interpeak latencies in almost 30 per cent of the fibromyalgia syndrome cases tested.Reference Rosenhall, Johansson and Orndahl18 According to our previous study of fibromyalgia syndrome cases,Reference Bayazit, Gursoy, Ozer, Karakurum and Madenci2 the absolute latencies of the I, III and V waves were abnormal and the interpeak latency of the I–III, III–V and I–V waves was prolonged on auditory brain stem reponse testing of the majority of patients. These findings suggest that brain stem dysfunction may be present in some patients with fibromyalgia syndrome, which may be responsible for the absence of contralateral suppression of TEOAEs in these patients. Dysfunction of the brain stem neural integrators may have an impact on the neural connections of the medial superior olivary complex, which in turn may lead to absence of contralateral suppression of OAEs.

The medial superior olivary complex fibres synapse with outer hair cells, and neural mediators also function in the transmission of stimuli in these synapses. Some agents can block contralateral suppression of OAEs, such as nicotinic antagonists, curare, alpha-bungarotoxin, kappa-bungarotoxin and the glycine antagonist strychnine.Reference Kujawa, Glattke, Fallon and Bobbin19 In fibromyalgia syndrome, there may be an increased excitatory amino acid release and a positive modulation of N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptors by glycine.Reference Larson, Giovengo, Russell and Michalek20 Accordingly, although neural mediators were not assessed in this study, alterations in such mediators might affect contralateral suppression of TEOAEs in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome.

Conclusion

Mechanisms related to the contralateral suppression of transiently evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAEs) seem dysfunctional in fibromyalgia syndrome patients. This dysfunction may be at the brain stem level, where the medial superior olivary complex is located, or in the synapses between medial superior olivary complex fibres and outer hair cells. Demonstration of a lack of contralateral suppression of TEOAEs can be used as a diagnostic tool in fibromyalgia syndrome patients.