Introduction

In recent years, universal basic income has moved from the fringes of academia to a staple of policy debates about the future of the welfare state. A common refrain repeated by policymakers and the media is that it is “an idea whose time has come” (eg. Reed & Lansley, Reference Reed and Lansley2016). To some extent, this relates to the challenges that many developed countries face, including precarious employment, inequality and the threat of technological unemployment (Widerquist, Reference Widerquist and Torry2019). Advocates of a basic income argue that it is the optimal solution to deal with these challenges by providing guaranteed income security to all, without the bureaucratic problems of the existing welfare state (Standing, Reference Standing2011).

Yet, there is often an implicit assumption that the idea is increasingly gaining traction within civil society and the public at large. Sometimes this is even explicitly stated as such (Holmes, Reference Holmes2017). The argument is that public support is “snowballing” as more policy announcements and public endorsements have enhanced the social legitimacy of the idea. Recent survey results in the European Social Survey (Roosma & van Oorschot, Reference Roosma and van Oorschot2020) that show surprisingly high support for basic income have done little to dispel this theory. On the other hand, the most visible test of public opinion – the 2016 referendum in Switzerland – revealed significantly different results, as only 23 per cent of voters backed the proposal. In this case, supporters can point to specific factors that influenced the result; none of the mainstream political parties supported the proposal and some campaigners argued for an unrealistically high level of basic income, without a specified funding mechanism. Yet, there is a sense that the more the proposal is scrutinised in political debate, the more public support begins to “wilt.” Thus, there are contradictory narratives of “snowballing” support on the one hand, and fragile or “wilting” support on the other.

We state that there are interlinked substantive and methodological reasons for the discrepancies in measured support across surveys. Firstly, basic income as an idea is multi-dimensional. In other words, there are many ways to frame or implement it as a policy proposal, and the precise details of a basic income scheme matter for its social legitimacy. While this is true for many policies, basic income is relatively unique; in that, the sheer scale of providing an income to every citizen or resident requires radical tax and/or welfare state reform to be implemented simultaneously. Relatedly, survey questions also vary considerably, most notably concerning the definition of a basic income provided, or lack of one, as well as the precise specification of a model. Finally, there are likely to be cross-national differences in support for the idea, which explain some of the variance in results.

In this paper, we test these arguments by examining the extent to which the precise model of basic income affects the level and determinants of support for the policy. We also use data from two countries, the UK and Finland, to act as case studies of the effects of model design across contexts. In this sense, our paper contributes to the debate about the robustness of public support for basic income, by revisiting survey results and examining which factors are responsible for particular support levels.

Overall, we find considerably more evidence to suggest that high support for the abstract idea of a basic income is fragile and susceptible to “wilting” once specific models are specified. Claims that support for basic income is “snowballing” will always be vulnerable to the question of which basic income. It is not just the overall levels of support that changes with the specification of policy details but the support of particular constituencies of voters. While there are certain groups that are generally receptive to the idea, the ability of political actors to mobilise them all will be questionable once they outline specific basic income proposals.

The first section of the article outlines the evidence from existing survey data on basic income and points out two of the key difficulties when studying the social legitimacy of basic income: public awareness and multi-dimensionality. The second section is concerned with the data and methods used for this study. In the subsequent sections, we explore recent surveys from the UK and Finland in more detail. The UK and Finland constitute particularly informative cases, as there have been several population-level surveys in both Finland and the UK in the last 4 years (2015–2019) on basic income. We then employ novel datasets in each country, with survey questions designed by the authors, to identify the levels and determinants of support for different models of basic income. We conclude with a discussion of what this means for the social legitimacy of basic income and future research on this topic.

A multi-dimensional basic income: support for which basic income?

As political interest in basic income has gathered pace, research on public attitudes has also grown. The release of the European Social Survey’s Wave 8, which included an item on basic income, has allowed for in-depth analysis across 23 countries. There have also been a number of other national and cross-national surveys, with at least 15 surveysFootnote 1 conducted in Finland alone in the last 5 years. Thus, recent publications have found that countries with lower levels of social spending and higher levels of insecurity are more supportive of basic income (Lee, Reference Lee2018), while at the individual-level, labour market risk, left-wing ideology and low-income predict support for basic income (Adriaans, Liebig, & Schupp, Reference Adriaans, Liebig and Schupp2019; Roosma & van Oorschot, Reference Roosma and van Oorschot2020; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2019). Some repeated surveys have pointed to increasing levels of support over time in Europe and the US (Holmes, Reference Holmes2017; The Hill, 2019), while the analysis of four identically worded survey questions across a 3-year period in Germany points to stability in the overall levels of support (Adriaans, Liebig, & Schupp, Reference Adriaans, Liebig and Schupp2019). Although this latter example dampens the idea of “snowballing” support in Germany, the consistent findings also give credence to the argument that these survey instruments provide a reliable estimate of public support for the idea.

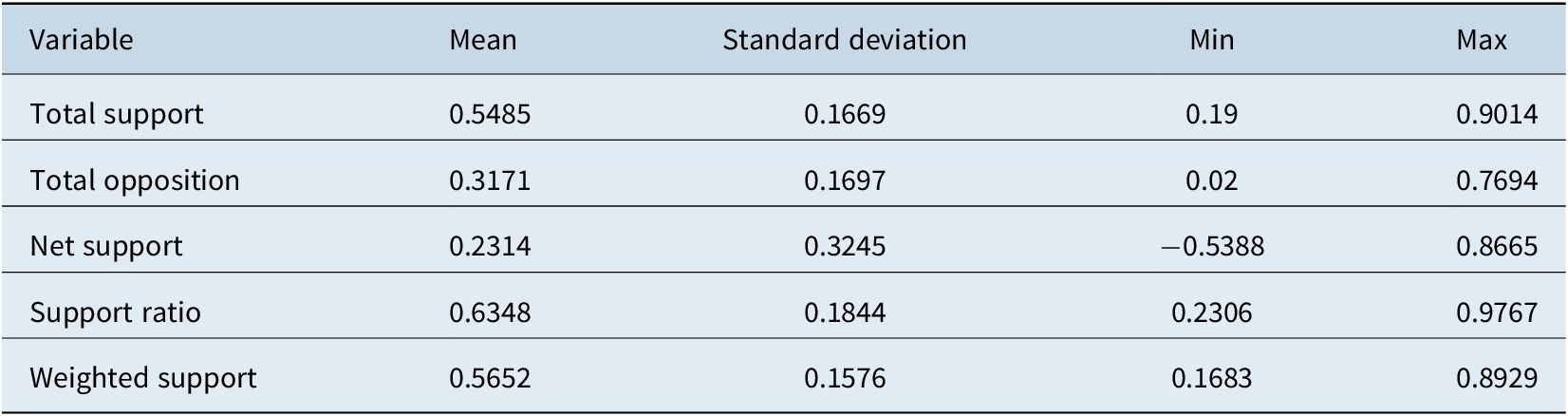

To supplement these findings, we reviewed alternative survey data on basic income, finding 110 different surveys, in 35 different countries with 24 different survey items.Footnote 2 The earliest survey, we found, that referenced a basic income, was conducted as part of the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) in March 1987, with the most recent in our list conducted in September 2019. Details of all the surveys included can be found online and key differences between them are discussed for Finland and the UK below.Footnote 3 Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the 110 surveys we collated. The first thing to note is that revealed support for basic income is generally high. On average, over half of respondents indicate support for a basic income: mean total support in a basic income survey is 54.9 per cent. Similarly, net support (ie. the difference in percentage terms between total support and opposition) is also positive on average: mean net support is +23.1 per cent. However, equally striking is the range of outcomes. Total support can be as low as 19 per cent but as high as 90.1 per cent, while net support can be as low as −53.9 per cent and as high as 86.7 per cent. We also calculate the ratio of supporters to opponents (“support ratio”) and provide a measure of support that accounts for the strength of opinionFootnote 4 (“weighted support”). Results for all four measures suggest the same thing: support for basic income is high on average but extremely variable.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of basic income surveys (N = 110).

However, there are two key reasons why results from these surveys are contentious in terms of gauging the social legitimacy of a basic income. Firstly, public awareness of the idea of a basic income is low. In 2016, only 23 per cent of respondents indicated that they fully understood the concept (Dalia Research, 2016). Non-attitudes (Converse, Reference Converse and Apter1964) and acquiescence bias beset survey research when respondents are ill-informed. This is inevitably more of an issue when conducting surveys on policies that do not exist and are not at the heart of mainstream political debate. Thus, while respondents may respond in a consistent manner to the same survey item, we cannot be certain that respondents have fully understood what a basic income is. Certain definitional features, such as its unconditionality and the required tax changes, are difficult to convey without biasing the results. Importantly, overall levels of support are likely to be highly sensitive to the precise survey question presented to respondents. Some survey questions do not provide a detailed definition of a basic income at all, while others emphasise certain features, or reasons, for implementing a basic income.

For example, the ISSP survey question (1989, 1994) simply asks how much they agree with the following statement: “The government should provide everyone with a guaranteed basic income.” Similarly, the question used in a comparative study of Finland and Sweden, as well as a study in Norway, was “What do you think about a system that would automatically guarantee a certain basic income to all permanent residents?” (Andersson & Kangas, Reference Andersson, Kangas and Standing2004; Bay & Pedersen, Reference Bay and Pedersen2006). Yet, the concept of a basic income is also used for conditional benefit systems. This is even the case in Finland, where the political debate about basic income has been comparatively salient and sophisticated.Footnote 5 Thus, there are concerns that respondents are indicating support for a minimum income scheme or a safety net, in general, rather than a universal basic income.

The second issue relates to the fact that basic income is multi-dimensional. Most existing analysis relies on survey data that provide a uni-dimensional measure of support for a basic income. Even questions that provide an extensive definition of a basic income, such as the European Social Survey (see Table 2), only ask about one policy and do not specify a number of important details. Yet, as the introduction to this special issue outlines, there is not only one model of basic income (De Wispelaere & Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004). In fact, basic income as a concrete policy proposal can vary according to its level and the benefits it replaces, as well as its funding mechanism. It can also be promoted as a “stepping-stone” or “cognate” policy where certain core features are compromised on, such as with a negative income tax or a participation income (Atkinson, Reference Atkinson1996). This is important because measuring support for a vague notion of basic income – with less technicalities specified – cannot tell us how much public support there is for specific models of basic income that could be realistically implemented.

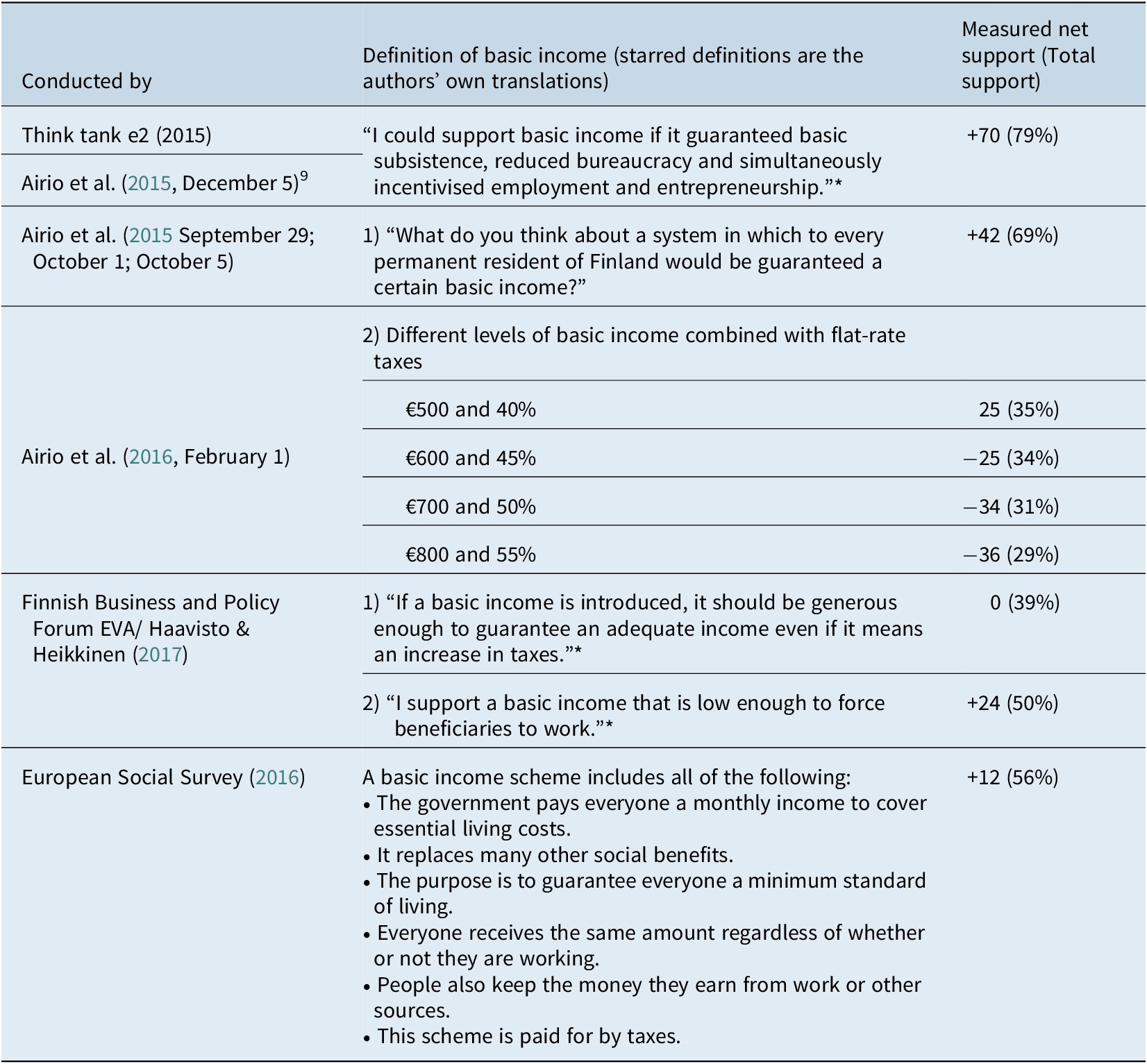

Table 2. An overview of four nationally representative basic income surveys carried out in Finland 2015–2017.

*Author’s own translation.

Although it is not entirely novel (eg. Andersson & Kangas, Reference Andersson and Kangas2002, Reference Andersson, Kangas and Standing2004; Bay & Pedersen, Reference Bay and Pedersen2006), the extent to which academic work has explored the change in support, driven by different models or frames of basic income, is limited. Two recent contributions have used conjoint survey experiments to identify how support is contingent on the design characteristics of a basic income model (Stadelmann-Steffen & Dermont, Reference Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont2019) and how support for basic income relates to competing welfare schemes (Rincón & Hiilamo, Reference Rincón and Hiilamo2019). However, while conjoint survey experiments are well suited to capturing the multi-dimensionality of a basic income, they are considerably more cognitively demanding for respondents. This could be a problem, given the lack of public awareness about basic income. Thus, here we adopt a different but complimentary approach. Firstly, we zoom in on examples of survey variation in the UK and Finland to provide a more vivid illustration than the examples given above. We then analyse new data in both countries that specify varying basic income models.

Methods

Case study selection

We examine public opinion in the UK and Finland because, relative to many other European countries, basic income has been a more salient issue, where major political parties have expressed support for the policy and/or included the policy in their manifestos. Importantly, this has also meant more interest in measuring public opinion with multiple basic income surveys in recent years to examine.

However, although interest in basic income has been relatively high in both countries, the implementation of a nationwide experiment in Finland means that we expect more awareness of the policy relative to the UK. This may make the results less variable across different models or frames. The existing institutional context also differs, with Finland usually classified as a social democratic welfare regime, with a combination of earnings related and basic flat-rate benefits, and the UK a liberal welfare regime, with a high degree of means testing and private provision (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990). The different contextual factors and a range of public opinion surveys allow comparison within and across contexts. However, the research design is not strictly comparative due to the variation in survey questions across the two countries, which is elaborated on further below. The aim of analysing two cases is not to test hypotheses about the effect of contextual factors on support for basic income, but to explore the extent to which our central argument about variation in the level and determinants of support for basic income holds in both cases.

Data and analysis

The data and analysis in Finland and the UK consist of two parts. First, we conduct a summary review of nationally representative basic income surveys carried out between 2015 and 2018 in both countries. The research reports were selected due to their similarities in terms of sampling and time, which draw attention to how survey wording can explain major differences in identified support.

Second, we analyse novel datasets that comprise multiple questions related to basic income. In Finland, the data were collected in August and September 2017 by the market research company, TNS Kantar (see more hereFootnote 6), which utilised multi-phase sampling (TNS Gallup Catibus). The interviews (n = 1,004) were carried out on telephone to minimise selection-bias and produce demographically balanced data. The data have been weighted using information from Statistics Finland (Tilastokeskus) and are thus nationally representative with respect to gender, age (15–79 years old population) and region (excluding the autonomous region of Åland). The survey questionnaire is described in more detail in Pulkka (Reference Pulkka2019).

In the UK, a professional polling company, Ipsos MORI, conducted the survey online on behalf of researchers from the University of Bath that designed the questions (see more details hereFootnote 7). A representative sample was drawn from Ipsos MORI’s (non-representative) omnibus panel and subsequently weighted based on population statistics sourced from Eurostat. Nevertheless, the use of an online survey can raise concerns about the sampling procedure, ie. the under-representation of certain groups, especially the digitally excluded, and data quality, ie. respondents providing satisficing answers (Frippiat et al., Reference Frippiat, Marquis and Wiles-Portier2010).

We focus on providing descriptive statistics and analysing the relationship between independent variables and support for basic income. We adopt a strategy of using bivariate probit regression models as a means of displaying these relationships in a concise and straightforward manner. We avoid using control variables to avoid complications in inference arising from differences in independent variables across the surveys. Thus, the results are equivalent to providing cross-tabular analysis, and the choice of using bivariate regression analysis is due to the ease of presenting all the relationships in a single table.

The dependent variable in both cases is a dichotomous variable (supports/does not support), recoded from the Likert scales provided in the survey (Finland survey was recoded from 1–2 to 1 and 3–5 to 0, while the UK survey was recoded from 1–2 to 1 and 3–4 to 0). Independent variables in the Finnish case were as follows: Gender (1 = male, 2 = female), Age group (1 = 15–24, 2 = 25–34, 3 = 35–49, 4 = 50–64, 5 = 65+), Education (1–7, 1 indicating the lowest educational attainment and 7 the highest attainment), Income group (Household’s gross income a year 1 = < 20,000 €, 2 = 20,001–35,000 €, 3 = 35,001–50,000 €, 4 = 50,001–85,000, 5 = 85,001–100,000 €, 6 = 100,001–120,000 €, 7 = > 120,000 €), Party preference (1 = right-wing parties (National Coalition Party, Centre Party, Christian Democrats, Finns Party and Swedish People’s Party) 2 = left-wing parties (Left Alliance, Social Democratic Party and Green League). In the UK, the independent variables were as follows: Gender (1 = male, 2 = female), Age (continuous variable divided by 10), Education (university graduate dummy (0, 1)), Income (binary variable: 0 = <£35 k a year, 1 = > £35 k a year), Party preference (binary variable: 0 = all other parties, 1 = Conservative Party, no preference coded as missing). It should be noted that the two surveys were not designed simultaneously, which explains the distinct survey items in the questionnaires. In other words, the study does not compare identical models in two separate countries, and hence the setting is not comparative in a conventional sense. However, as mentioned above, analysing several divergent models of basic income in both countries provides a more reliable evidence base for making claims about the effect of model specification or survey design.

Basic income surveys in Finland

Table 2 presents an overview of five nationally representative surveys carried out in Finland between 2015 and 2017. What stands out in the table is the considerable variation (29–79 per cent) of identified support in a period of only 3 years. Some of the variation could naturally reflect changes in public sentiment, but a more plausible explanation relates to survey design, given considerable variation also exists within surveys. As in the previous analysis, the questions vary according to whether they provide a definition of basic income and whether a model of basic income is specified. Yet, some descriptions are also loaded with favourable or unfavourable assumptions linked to the implementation of a basic income.

A comparison of the survey questions suggests that the absence of a definition and a specified model (ie. no mention on the level, replaceable benefits, or taxation) is associated with high support (e2, 2015; Airio et al., Reference Airio, Kangas, Koskenvuo and Laatu2015 September 29; October 1; October 5). Yet, when this is coupled with a favourably loaded question (e2 2015), identified support is even higher. It is hardly surprising that a reform is highly popular if it is assumed to not only guarantee basic subsistence and reduce bureaucracy but also incentivise employment and entrepreneurship.

The results also suggest that certain modes of implementing a basic income (Airio et al., Reference Airio, Kangas, Koskenvuo and Laatu2016, February 1; Haavisto & Heikkinen, Reference Haavisto and Heikkinen2017) lead to relatively low support. When Airio et al. (Reference Airio, Kangas, Koskenvuo and Laatu2016, February 1) asked respondents’ views on different levels of basic income combined with flat-rate taxes, support collapsed from 69 per cent in their initial survey to 29–35 per cent. In a Nordic welfare state, such as Finland, flat-rate tax rates are a political non-starter. Although flat-rate tax models may be justified for simplicity reasons when calculating the costs of different basic income models, incorporating them into a reform unsurprisingly has a negative effect on the identified support.

Yet, this is not solely related to flat taxes. When the Finnish Business and Policy Forum EVA (Elinkeinoelämän valtuuskunta) (Haavisto & Heikkinen, Reference Haavisto and Heikkinen2017) connected “adequate income” with “higher taxes,” the measured support was also lower at 39 per cent. The EVA survey also indicates that public support is relatively high for a basic income that implies diluting the current level of social security (Haavisto & Heikkinen, Reference Haavisto and Heikkinen2017), although lower than for the questions that provide a more abstract definition of basic income (e2, 2015; Airio et al., Reference Airio, Kangas, Koskenvuo and Laatu2015 September 29; October 1; October 5). Given the crucial role that the activation paradigm plays in the Finnish basic income discussion (Perkiö, Reference Perkiö2020), references to “work requirements” likely increased support among respondents who have a more critical stance towards basic income. Finally, the European Social Survey question defines basic income in more detail than the preceding surveys, albeit with a moderately loaded assumption to guarantee everyone a minimum standard of living. It implies that basic income is supplementary (ie. replaces most of other social benefits but not all) and is set at a relatively high level (ie. covers living costs). However, it does not provide an opportunity to explore support for different models.

This gap was addressed by data collected as part of a study exploring the Finnish view on the future of work (Pulkka, Reference Pulkka2019). The survey referred to a widely accepted definition of basic income by the Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN), which defines basic income as a universal, unconditional and individual cash payment made to all without means testing or work-requirement. Before presenting the models, respondents were also informed that the effects on the income distribution are dependent on the level, replaceable benefits and applied tax system. Respondents were informed that €560 is the current net level of basic security benefits.Footnote 8 This also corresponds to the amount given in the Finnish basic income experiment, which still was underway when the data were collected in August 2017. Given media discussion around the experiment was broadly positive (Mäkkylä, Reference Mäkkylä, Kangas, Jauhiainen, Simanainen and Ylikännö2020), this may have influenced the results.

To acknowledge the multidimensional nature of basic income, specific attention was paid to the level and the benefits replaced. Respondents were informed that a basic income either maintains eligibility to housing allowance and earnings related benefits (supplementary basic income [often referred to as a “partial” basic income in the Finnish debate]) or replaces them (replacement basic income [often referred to as a “full” basic income]). The level of basic income was either lower than current basic security benefits (< €560 a month), identical to the current level (€560 a month), higher than the current level (> €560 a month), substantially higher than the current level (€1,000 a month) or even higher than the average level of earnings related benefits (€1,500 a month). References to taxation were excluded to avoid potential issues with confusion about gross and net taxation in relation to a basic income (Widerquist, Reference Widerquist2017) and aversion to flat-rate taxes. Previous studies in Finland have shown that tax references in surveys are particularly sensitive (Forma et al., Reference Forma, Kallio, Pirttilä and Uusitalo2007, p. 16). This was also designed to complement existing evidence in the Finnish context, given the availability of public opinion on basic income combined with flat-rate taxes.

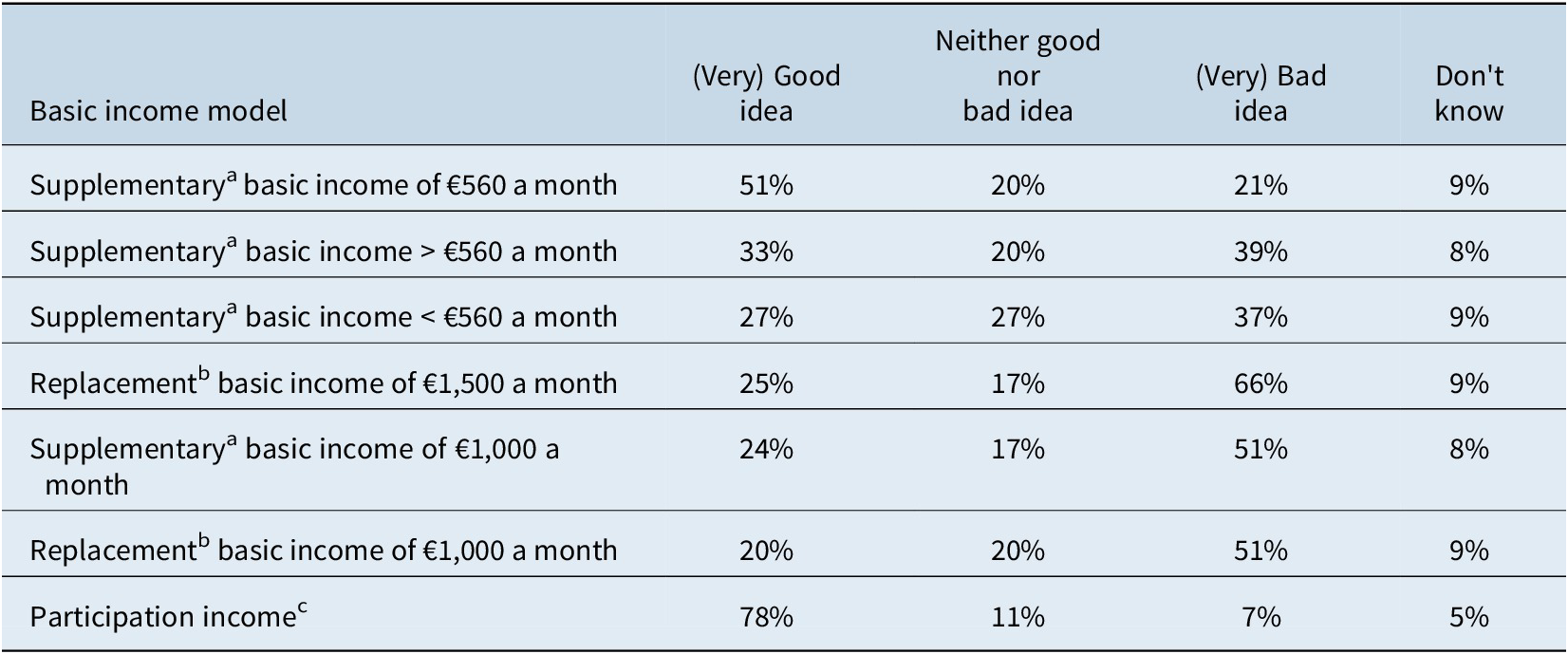

The results obtained from the survey are summarised in Table 3. The results indicate that the level of basic income has a considerable effect on overall support. The Finnish public are most supportive of a basic income that would maintain the current level of social security (partial basic income €560 a month), while support for increasing social security is low.Footnote 9 Support appears to be lowest for the most radical models: both replacement basic incomes and the very high supplementary basic income suggesting that flat-rate taxes alone did not explain the aversion to such policies in previous studies. However, contrary to the EVA survey, there is also less support for reducing the level of support than moderately increasing it, when expressed in monetary terms. Finally, the results show that, even for the most popular model, support is dwarfed by that of participation income, which is as high as 78 per cent.

Table 3. Support for six various basic income models and participation income in Finland.

a Maintains eligibility for housing allowance and earnings related benefits.

b Withdraws eligibility for housing allowance and earnings related benefits.

c Eligibility for social assistance and basic security benefits requires participation in activation measures that can be defined by the unemployed in a more autonomous manner than currently (eg. voluntary work, studying, caring for close relatives or leisure activities).

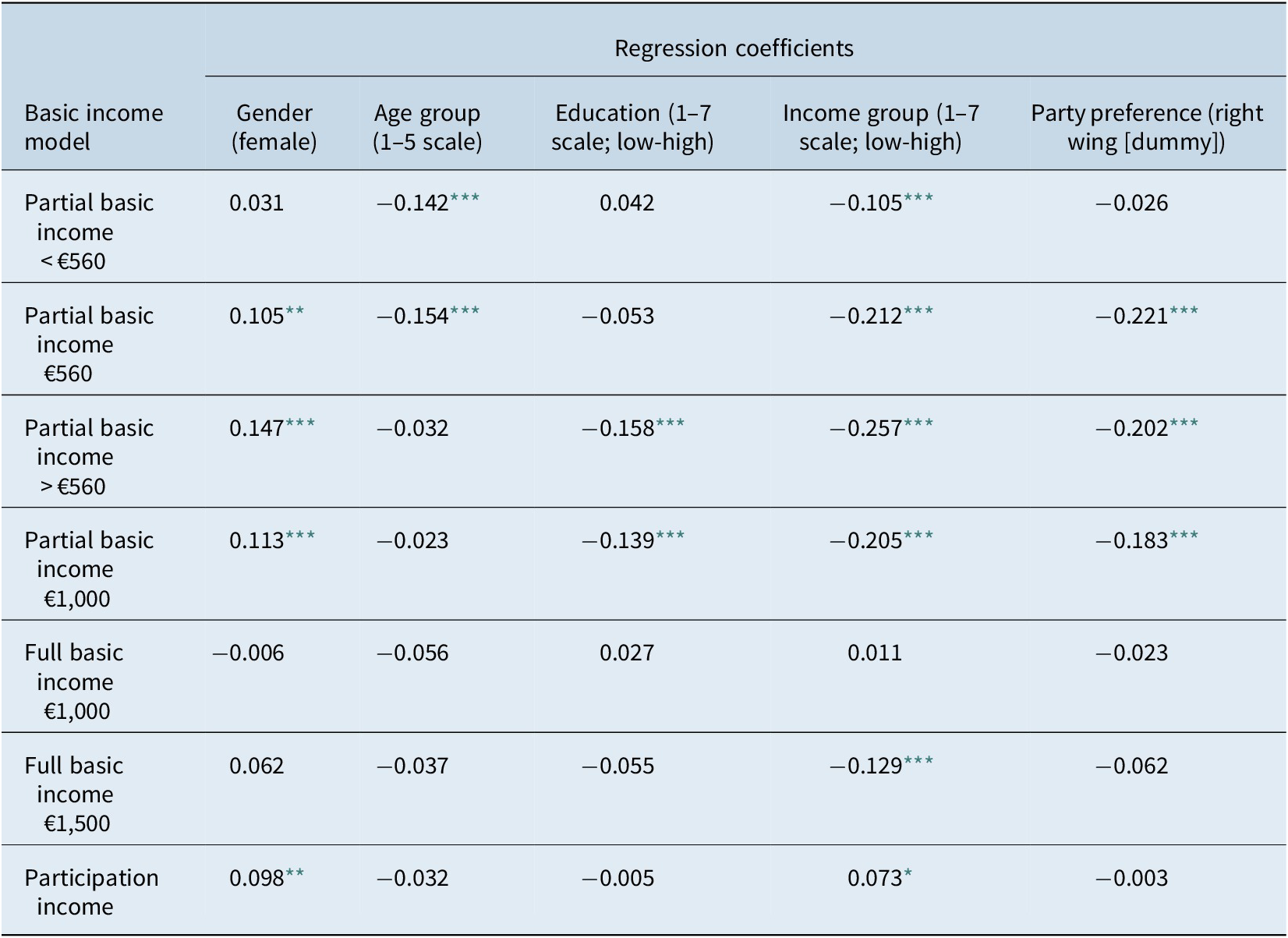

Finally, Table 4 shows how certain sociodemographic characteristics explain support for different models. For example, while young people are generally more supportive of a basic income, this is only significantly the case for models that either maintain or lower the level of support. Women are significantly more likely to support models that imply maintaining or increasing support but not those that do not, and also more likely to support a form of participatory income. Meanwhile, education, income and right-wing partisanship predict opposition to models that increase the level but not necessarily those that do not. However, when control variables are included (see Pulkka, Reference Pulkka2020), education is no more a statistically significant determinant of support. This shows the varying constituencies that may be mobilised for specific models of basic income rather than the abstract idea.

Table 4. Determinants of support for different basic income models in Finland (Bivariate probit regressions; Don't know excluded).

*** p ≤ 0.001.

** p ≤ 0.01.

* p ≤0.05.

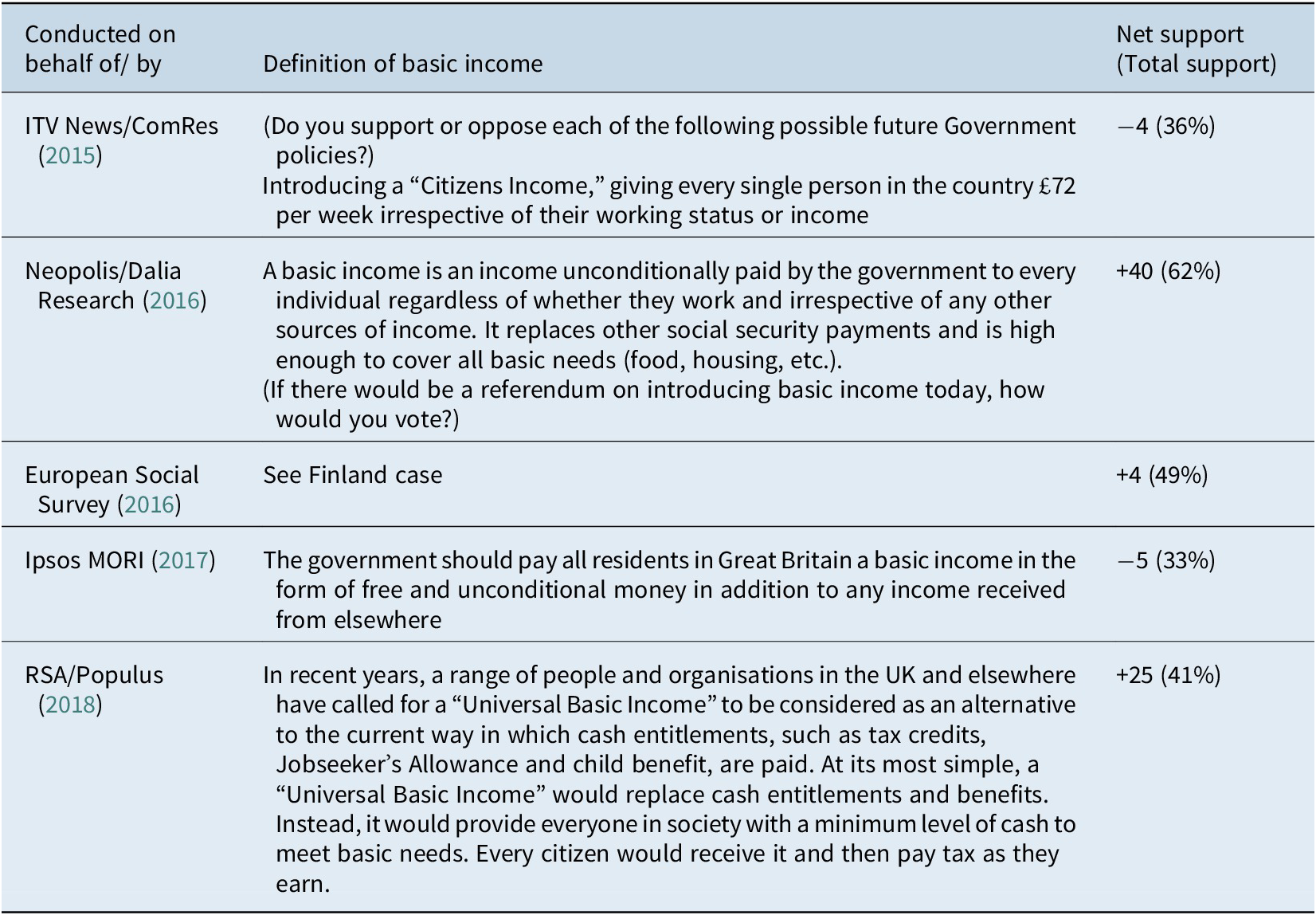

Basic income surveys in the UK

Table 5 presents six nationally representative surveys carried out in the UK between 2015 and 2018. It is immediately noticeable that overall levels of support do not vary (33–62 per cent) as dramatically as in the Finnish case. There is an obvious reason for this, which is that the survey questions are less heterogeneous across the surveys. All of the questions provide a definition of basic income and avoid loaded descriptions other than, perhaps, the Ipsos MORI survey, which refers to “free and unconditional money.”Footnote 10

Table 5. An overview of six nationally representative basic income surveys carried out in the UK 2015–2018.

The survey questions also do not specify a model of basic income except in the ITV News/Com Res poll. Mirroring the Green Party’s policy proposal at the time,Footnote 11 the ITV News survey described a level of £72 per week, which was equal to the level of the UK’s flat-rate unemployment benefit, Job Seekers’ Allowance (JSA). The specification of the level of basic income may explain why support was lower than the average, echoing the pattern that was visible in the Finnish case and in the review of all surveys. Likewise, the reference to “free” money in the Ipsos MORI survey, which is a loaded term, may explain the fact it exhibits the lowest levels of support. The differences between the other three survey questions are more subtle as all provide an extensive definition of basic income. However, the fact that the European Social Survey (ESS) definition explicitly mentions that the basic income is paid for by taxes may explain why measured support is lower.

As mentioned before, the most obvious gap is the lack of a survey testing support for different models or modes of implementation for a basic income. The Neopolis/Dalia Research, Ipsos MORI and RSA/Populus surveys all include items about whether particular arguments for and against basic income are persuasive but do not measure how support shifts as different models of basic income are specified.

Moving onto the dataset with multiple basic income questions, the policy was introduced to respondents at the start of the relevant section of the survey as follows:

As you may be aware, some countries are considering introducing a basic income.

If introduced in the United Kingdom, this would provide a regular income paid in cash to every individual adult in the UK, regardless of their working status and income from other sources. In other words, it would be:

• Universal (ie. paid to all),

• Unconditional (ie. paid without a requirement to work); and

• Paid to individuals (rather than to a household).

Then, respondents were asked the following question:

Assuming the level would be set roughly at the amount the UK Government judged to be necessary to cover basic needs, eg. food and clothing (but not housing costs), to what extent would you support or oppose the UK Government introducing a basic income…

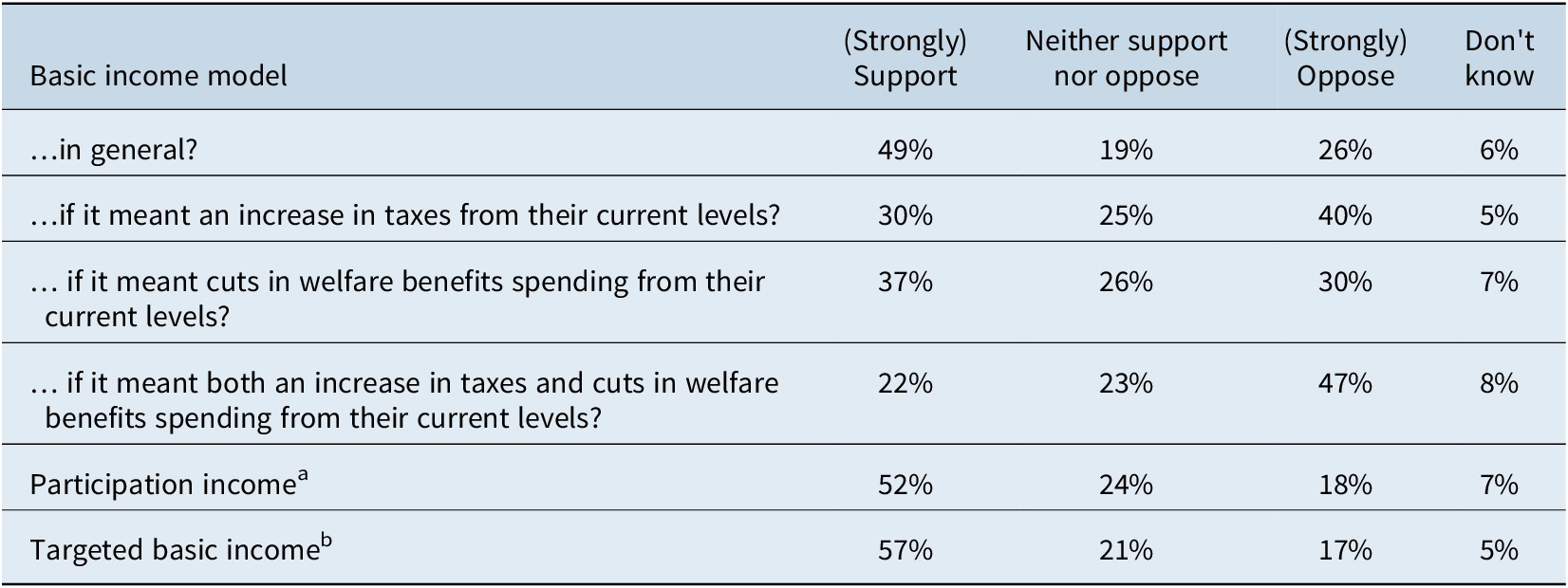

The question was completed by one of the first four lines in Table 6.

Table 6. Support for six basic income models and “cognates” in the UK.

a Only paid to those who are in work, in training, doing voluntary work or pensioners.

b Only paid to those on low incomes.

As in previous surveys, headline support for a basic income is high with 52 per cent responding “Strongly support” or “Tend to support.” However, Table 6 also shows that support “wilts” when a funding mechanism is specified, whether that is an increase in taxes or cuts in welfare benefits, although the former affected support more. Specifying that both would be required (as many proposed schemes suggest) shows that opposition to such a policy is more than double the support. Of course, unlike the Finnish data, we do not specify precisely what the level of a basic income would be nor do we specify the precise taxes or cuts. This may provoke respondents to assume the worst, ie. that tax increases and benefit cuts would be greater than in reality. However, this simply highlights the challenges that advocates of a basic income are likely to face: initial public support is vulnerable to the mere mention of tax rises or benefit cuts.

The next two questions concern basic income “cognates,” with respondents asked if they would support a participation income and a targeted basic income (the definitions of these policies are shown at the bottom of Table 6). The results show that public support is higher when a basic income is limited to deserving groups or targeted at those on a low-income, both violating central principles of a basic income. Of course, taxes are not mentioned in reference to these cognates (although they are asked sequentially after the question about a basic income funded through taxes).

Finally, we turn to the determinants of support for different models of basic income and “cognates” shown in Table 7. The differences for partisanship are the starkest. While Conservative voters are significantly less likely to support a basic income in general, or when it is financed by tax increases, this is reversed for a basic income that reduces the level of existing benefits or a participation income. Women are significantly more likely to oppose a tax-financed basic income but also supportive of a participation income. Finally, while education and income do not predict support for a basic income, in general, higher education and high income are significantly associated with support for a basic income implemented alongside benefit cuts. Interestingly, university graduates are also more likely to support a tax-financed basic income, and those on a high income are more supportive of a participation income. Again, this shows the shifting constituencies of support for different models of basic income in the UK.

Table 7. Determinants of support for seven basic income models and “cognates” in the UK (Bivariate probit regressions; Don't know excluded).

*** p ≤ 0.001.

** p ≤ 0.01.

* p ≤ 0.05.

Discussion

In this paper, we have sought to draw on previous surveys and new data to explain how support for a basic income policy – universal, unconditional and individual at its core, but with many unspecified technicalities – is contingent upon the definition provided and the specified model. The findings from both Finland and the UK point to one clear conclusion: recent results are likely to overstate the social legitimacy of basic income, ie. if we understand basic income more broadly than the abstract idea. In the abstract, the idea of providing a guaranteed basic income to all is popular in many countries. However, the extent of that support appears to be inversely related to the level of detail provided about the policy, particularly when the costs are clearly cited.

In the Finnish and UK analysis, we took divergent approaches to conveying the consequences for taxation. In the Finnish case, we avoided mention of taxes and relied on respondents inferring from the specified level what the implications for tax were likely to be. In the UK case, we cited tax increases directly in two of the survey items. However, it is striking that, in both cases, whether stated or implied by higher levels of payment, overall levels of support dropped considerably. It is clear that support for basic income is particularly vulnerable to concerns about rising costs. Similarly, support dropped in both cases for models that would reduce existing levels of social security, despite different ways of conveying that. The results suggest that future research could explore how cost and tax framing affect support for a basic income scheme. While some work has already shown that support is conditional on the forms of taxation (Rincón & Hiilamo, Reference Rincón and Hiilamo2019), and the multiple implications of policy costs (Bechtel et al., Reference Bechtel and Liesch2020), there is still room to analyse how different taxation models, framings and cost calculations have an effect on support.

These findings complement existing research on the multi-dimensionality of basic income, where an increase in taxes (be it Value Added Tax, personal income taxes, or transaction taxes) reduces support relative to cutting back government expenses, although the effect is not significant (Stadelmann-Steffen & Dermont, Reference Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont2019). Interestingly, our findings here may explain why the difference in support between taxes and cuts is not significant: no funding mechanism is popular at all. Although the UK case suggests cuts to social security would elicit more support than raising taxes, our findings in Finland confirm previous work that finds cutting back existing welfare is also an unpopular option (Rincón & Hiilamo, Reference Rincón and Hiilamo2019). Another important point is that even the most popular models of basic income reveal less support than available alternatives to basic income such as a participation income (in both countries) and a basic income restricted to those on a low income (in the UK). This raises an important question about the political feasibility of a universal and unconditional basic income: why would political actors advocate for a less popular policy proposal?

The multi-dimensionality of basic income also matters for who supports the policy as we find varying constituencies for different basic income models. Some findings are consistent in both the UK and Finland. For instance, across both contexts, women and high-income individuals are supportive of participatory forms of basic income. We also find that right-wing partisanship is significantly associated with opposition to generous basic income schemes but not those that imply retrenchment or participation. However, while lower incomes and lower levels of education broadly predict support for basic income in Finland, this is not the case in the UK. Indeed, for models of basic income that imply some retrenchment of existing benefits, high-income individuals are more supportive in the UK. The variability of predicted support across different models also poses problems for the political feasibility of a basic income. The coalition of supporters behind basic income in the abstract appears to shift once different models are specified, confirming past discussion of the problem of “persistent political division” (De Wispelaere, Reference De Wispelaere2016).

When designing future research for identifying public support for basic income, we suggest there are two main strategies for dealing with the issues we identify. Firstly, quantitative methods, especially experiments, have the potential to assess the multi-dimensionality of basic income and the sensibility of public opinion to competing frames and dimensions. This is essential if we want to understand how contextual debates shape preferences towards these policies and how much support there is for competing models in a given context. In particular, research should focus on forcing respondents to appreciate the relevant trade-offs in basic income design. Secondly, as two other papers in this special issue show, qualitative research can also be extremely useful for interrogating the fundamental reasoning behind attitudes to basic income. A qualitative interview setting may also allow respondents develop a better understanding of the policy in question and prevent the researcher form inferring on non-attitudes. In both cases, research should acknowledge that the multiple dimensions of a basic income are likely to invoke different responses. Where possible, future research should embrace this complexity and explore it further.

Acknowledgements

Ville-Veikko Pulkka acknowledges the financial support provided by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 822296 (BEYOND 4.0) and the Finnish Cultural Foundation (Suomen Kulttuurirahasto) in the research, authorship and publication of this article.

Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Notes on Contributors

Joe Chrisp recently completed his PhD on the political economy of basic income in Europe at the University of Bath, having studied at the University of Oxford and the University of Bristol. He is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Comparative Politics at the University of Bergen, Norway. His research interests span various themes in public policy, comparative politics and welfare states and is currently working on a project examining the growth in public consultations across EU member states.Ville-Veikko Pulkka is completing his PhD on the future of work and its implications for social policy change in the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Helsinki, Finland. Prior to his current position, Pulkka worked as a researcher at the Social Insurance Institution of Finland (Kela) and was a member of the research group responsible for the preparations of the Finnish basic income experiment. His research interests are focused on microsimulation-based comparative analyses, welfare attitudes, feasibility of basic income and social policy experimentation. Leire Rincón García is completing her PhD at the University of Barcelona. In her thesis, she is looking at individual preferences for welfare state reform, in particular different forms of cash transfers. During her PhD she has been a visiting student at the University of Oxford, and previously she completed her BSc in Politics and International Relations at the University of Bath. Today her research interest cover a wide range of topics from the politics of redistribution, to gender-based and sexual violence, preferences and behaviour of political elites in processing information.