1. Introduction

This qualitative single case study explores how contemporary Populist Radical Right (PRR) parties in Hungary frame social policy issues. Mainstream political parties can be powerful agents of socialisation and are worthy of study because how these parties strategize and mobilise their constituents has consequences for democratic change (Reference HermanHerman, 2016). A troubling trend for democracy in Central Eastern European (CEE) in recent years is the rise of the populist far right. Hungary was once the forerunner of democratic performance but since the 2010 and 2014 elections, is run by a populist far right party (Fidesz), with a populist extreme right party (Jobbik) as the official opposition. The use of inimical populist constructions of ‘us’ and ‘them’ (Reference LeClau and PanizzaLeClau, 2005; Reference ReinfeldtReinfeldt, 2000) can open space for political polarisation and deference to a ‘personalist authority’ as seen in Hungary (Reference EnyediEnyedi, 2016a, Reference Enyedi2016b; Reference PappasPappas, 2014, pp. 3–4). As PRR parties move into the mainstream, and therefore have policy-making and agenda-setting power, understanding the features of PRR ideology is an increasingly important task (Reference PirroPirro, 2016).

While the PRR is often associated with welfare chauvinism, an exclusionary programme of distributing social benefits, there is little research on how these parties articulate their positions. Nordensvard and Ketola argue that the welfare nation state is an important component of populist discourse in Finland and Sweden, especially concerning outgroups like immigrants. This form of populist discourse is exclusionary and tightly linked with nationalism and perceived threats to sovereignty (Reference Nordensvard and Ketola2015, p. 357). There are good reasons to suspect that nationalist and populist reframing of welfare policy can also be observed in the Hungarian case. For example, writing on Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán's social policies from 2010 to 2014, Szikra finds that Fidesz’ welfare reforms since taking office are increasingly polarising society along income and ethnic lines (Reference Orbán2014).

What we do know about the PRR and welfare chauvinism comes mainly from Western and Northern European cases. This research contributes to the literature by investigating PRR framing strategies with a CEE case study. In addition to identifying the frames and framing strategies of the PRR in Hungary, the paper further aims to clearly differentiate between nationalism and populism. This is important because recent research suggests there is conceptual conflation between the two (Reference De Cleen, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and OstiguyDe Cleen, 2017; De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Reference De Cleen and Stavrakakis2017) and that nationalism is the defining feature of these parties (Reference RydgrenRydgren, 2017). Taking these claims seriously allows for an opportunity to examine the character of the PRR with more precision. The paper employs a critical frame analysis of party manifestos and key speeches to reveal how social policy issues in Hungary are constructed (i.e. deserving vs. undeserving poor) in five social policy areas: pensions, health care, unemployment, social assistance, and family allowances. In line with social movement theory, I contend that while particular framing strategies do not directly cause populist support, framing does indirectly set the agenda and influence policy-making decisions (Reference PytlasPytlas, 2015). The article begins by clarifying concepts, then the research strategy is presented followed by a summary and discussions of the findings, and wraps up with concluding remarks based on the findings.

2. Populism and nationalism in the populist radical right: interlocking but not interchangeable

2.1. Populism

While the search for a precise definition of populism continues to be hotly debated, the bulk of the research can be divided into three main schools of thought. Scholars such as Weyland (Reference Weyland2011) imagine populism as a political style disengaged from ideology (see also Reference Moffit and TormeyMoffit & Tormey, 2014), whereas others (Reference Albertazzi and McDonnellAlbertazzi & McDonnell, 2008; Reference StanleyStanley, 2008) conceptualise populism as an ideology and most famously, as a ‘thin-centred ideology’ attached to ‘host ideologies’, such as nationalism (Reference MuddeMudde, 2004; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013a). Others still, conceive of populism as a discursive enterprise centred around a set of ideas (Reference HawkinsHawkins, 2009) that manifest as a discourse (Reference Laclau and MouffeLaclau & Mouffe, 1985), a discursive frame (Reference AslanidisAslanidis, 2016), or as an ongoing process of reframing ‘us and them’ (Reference Mayer, Ajanovic and SauerMayer, Ajanovic, & Sauer, 2014).

This paper subscribes to the Hawkins definition of populism as a set of ideas grounded in particular cultural contexts (Reference Hawkins2009, p. 1043). Populist appeals to the ‘common person’, the ‘politics for the people’ versus the ‘corrupt elite’ (Reference MuddeMudde, 2004), are expressed by a particular discourse strategy and line of argumentative reasoning that can occur anywhere along the left-right political spectrum (Reference BlokkerBlokker, 2005, p. 386; Deegan-Krause & Haughton, Reference Deegan-Krause and Haughton2009; Reference HawkinsHawkins, 2009).

2.2. Nationalism

Scholars across disciplines have long been interested in questions of nationalism and how to understand it. Moving past early primordial theories of nationalism as inherent, Anderson defines nationalism as an ‘imagined political community’ (Reference Anderson1991 [Reference Anderson1983]). Similarly, Gellner (Reference Gellner1994) contends that nationalism is an invented tradition resulting from the development of the modern nation-state system and is not natural. A strength of Gellner's argument is the correlation drawn between political legitimacy and nationalism (Reference HarrisHarris, 2009, p. 53). Mudde understands nationalism more broadly as ‘nativism’. Nativism is an ideology that only members of the core group belong to the nation and outsiders pose a threat. In contrast to ethnic nationalism that is inherently exclusive, nativism allows for inclusive forms of nationalism that do not compromise the tenets of liberal democracy (Reference MuddeMudde, 2007, pp. 17–19).

Others, like Breuilly (Reference Breuilly1993) and Waterbury (Reference Waterbury2006, Reference Waterbury2010), perceive nationalism as an elite tool of power where politicians draw on ‘banal nationalist’ (Reference BilligBillig, 1995) constructions of ‘us versus them’ to reify and reproduce narratives of the national interest, especially vis-á-vis the outside international context, as a powerful rhetorical device. In a similar vein, Brubaker (Reference Brubaker1996, Reference Brubaker, Iglesias, Stojanović and Weinblum2013 [Reference Brubaker, Iglesias, Stojanović and Weinblum2011]) conceptualises nationalism as an ongoing discourse process of nationalising. Further to that point, any single definition of nation, nationalism, and nationality will always be contested as one group, especially a majority, will always be favoured in terms of identity, policy, etc. (Reference CalhounCalhoun, 1997, p. 98). That creates problems for minorities who may not fit into the dominant group, especially under oppressive conditions where status and rights may be compromised. Elite expressions of nationalism then, are always potentially controversial, especially exclusive forms based on concepts of ethnicity as seen in CEE by ‘national-populists [that] tend to be anti-Europe and create myths such as ‘true Hungarianness or Polishness’ into an ‘us vs. them’ philosophy’ (Ágh, Reference Ágh1998, pp. 65–66). With this understanding, groups perceived as outsiders of the imagined nation, such as, for instance, immigrants, the Roma, and sexual minorities, are prime targets for discrimination and resentment (Ágh, Reference Ágh1998, p. 106). Focusing on how elites use nationalism through discourse and narratives helps shed further light on how nationalism works, with attention to the outcomes and implications of such strategies. This maneuver takes the debate beyond trying to pinpoint a precise definition of nationalism, which like populism, is an inherently fuzzy concept.

2.3. Conceptual clarity on the populist radical right

In turning attention to the populist radical right, it is imperative to delineate populism from nationalism. Scholars continue to argue, however, that separating the two is not straightforward. In earlier work, some went as far as calling populism ‘a kind of nationalism’ (Reference Stewart, Ionescu and GellnerStewart, 1969, p. 183). Akkerman (Reference Akkerman2003, p. 151), in an analysis of the populist radical right, writes that the meaning of ‘the people’ refers to ethnos rather than demos. For example, ‘the people’ can be defined along ethnic and nationalist terms and outgroups often include immigrants as a cultural and economic threat (Reference DerksDerks, 2006, p. 181). Yet, in some instances, articulations of the ‘the people’ may refer to both (Reference JansenJansen, 2011). In the same vein, Vincent (Reference Vincent, Freeden, Sargent and Spears2013, p. 454) talks about the populist notion of nationalism, which is often the sources for populist mobilisation in the first place (see also Pankowski, Reference Pankowski2010). Therefore, nationalism may be understood as ‘the notion of popular self-government, the idea that government is carried out either by the people or for the people, in accordance with their ‘national interest”’ (Reference HeywoodHeywood, 2012, p. 179). In other words, nationalist mobilisation gains a populist character if nationalist actors argue that they seek to represent ‘the people’, i.e. the nation, against the privileged elites (Reference HobsbawmHobsbawm, 1990, p. 20). Not surprisingly, many parties (from the left and the right) that are often described as populist, equally share nationalist features (cf. Halikiopoulou, Nanou, & Vasilopoulou, Reference Halikiopoulou, Nanou and Vasilopoulou2012). The question that arises then is, if and how these two concepts can be separated. Given the often-occurring conflation between populism and nationalism, it is especially important for this paper to make the theoretical distinction to avoid empirically conflating the framing of social policy issues in Hungary as populist when really, they are nationalist (and vice-versa). Since the 1970s, the rise of the ‘new right’ has changed the political landscape by politicising issues normally relegated to the private sphere, such as the construction of the family, national identity, and so on (Reference Kirkham and SatzewichKirkham, 1998, p. 245). New rightists challenged the liberal order by advocating a return to so-called traditional norms and values. In the European context, a particular strand of right-wing populism that excludes immigrants and minorities has been on the rise since the 1980s (Reference IgnaziIgnazi, 2003; Reference McGann and KitscheltMcGann & Kitschelt, 1995; Reference MuddeMudde, 2007; Reference NorrisNorris, 2005). Rightist populism has captured widespread academic attention, with many simply referring to these parties as ‘populist’. This simplification comes at a theoretical cost as ‘populism’ neither defines these parties in a meaningful way nor is their main feature (Reference De Cleen, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and OstiguyDe Cleen, 2017; De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Reference De Cleen and Stavrakakis2017; Reference RydgrenRydgren, 2017).

The PRR is a specific party family across Europe with common elements such as authoritarianFootnote 1 leanings and a style of populism that excludes certain minority groups from ‘the common people’ (Reference MuddeMudde, 2007; Reference PirroPirro, 2014). This party family is first and foremost derived from a far or extreme right tradition with exclusionary nativism at the core (Reference MuddeMudde, 2007; Reference RydgrenRydgren, 2005). The far or extreme right is conceptualised as, ‘A political ideology revolving around the myth of a homogenous nation – a romantic and populist ultra-nationalism hostile to liberal, pluralistic democracy, with its underlying principles of individualism and universalism’ (Reference Minkenberg, Melzer and SerafinMinkenberg, 2013, p. 11). Rydgren stresses that the most important feature of PRR discourse is in fact exclusionary ethnic nationalism, which influences the populist features (Reference Rydgren2017). Similarly, De Cleen (Reference De Cleen, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017) and De Cleen and Stavrakakis (Reference De Cleen and Stavrakakis2017) advocate for a discourse approach to better understand PRR climates as characterised by the nationalist rhetoric used to frame populist arguments. They point out that for both populist and nationalist politics, the nation-state is the main level of policy and so references to ‘the nation’ are inherent to both (Reference De Cleen and Stavrakakis2017). The strongest point of conflation occurs when trying to define ‘the people’, a notion central to both populism and nationalism. De Cleen & Stavrakakis contend the nationalist construction of the people is defined by citizens versus non-members (can include other nations), with the populist construction of the people as an underdog to the establishment/some sort of elite (Reference De Cleen and Stavrakakis2017).Footnote 2 For the purpose of my empirical analysis, I maintain this differentiation.

3. Welfare Chauvinism and the PRR

3.1. From Western Europe with love?

One feature of PRRs in Western Europe that has attracted the interest of scholars is their change into welfare chauvinist parties. Since the early/mid-1990s, parties such as the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) and the Front National (FN) have turned their focus on social policy issues to advocate pro-welfare positions (Reference Lefkofridi and MichelLefkofridi & Michel, 2014, p. 19). This is in contrast to most of the positions PRRs in Western Europe adopted early on, where they would campaign on neo-liberal platforms (Reference RovnyRovny, 2013). Yet, as opposed to Social Democratic Parties, for instance, most PRRs adopted a pro-welfare position but would only grant benefits to those considered a legitimate part of the nation. This particular combination of egalitarian views with restrictive views on who is deserving is known as ‘welfare chauvinism’ (see Andersen & Bjørklund, Reference Andersen and Bjørklund1990; De Koster, Achterberg, & van der Waal, Reference De Koster, Achterberg and van der Waal2012; Reference DerksDerks, 2006; Reference MuddeMudde, 2007; Reference RydgrenRydgren, 2006; van der Waal, Achterberg, Houtman, de Koster, & Manevska, Reference van der Waal, Achterberg, Houtman, de Koster and Manevska2010).Footnote 3 PRRs, by adopting these positions, were also found to influence the positions of mainstream parties. For instance, conservative parties, under pressure from PRRs, would adopt more critical positions towards immigrants while, at the same time, changing their positions towards a more pro-welfare position (Schumacher & Van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and Van Kersbergen2016). Today, these positions make up part of the PRR's ‘New Winning Formula’ (Reference De LangeDe Lange, 2007, p. 411). In some cases, the PRR's shift in positions on welfare benefits coincided with an increasing agreement among citizens to restrict welfare benefits to ‘our own’ (Andersen & Bjørklund, Reference Andersen and Bjørklund1990). This view was particularly prominent in the 1990s when societies became more diverse as a consequence of a greater influx of immigrants (Reference Crepaz and DamronCrepaz & Damron, 2009). In contrast to many Western European countries, however, many Eastern European countries did not experience a larger influx of immigrants. In some cases, like Hungary, most immigrants came from neighbouring countries and were returning Hungarians (Juhász, Reference Juhász2003). Nevertheless, attitudes towards welfare benefits are often in line with the spirit of welfare chauvinism. Mewes & Mau for instance, find that welfare chauvinism, i.e. being in favour of restricting benefits to Hungarians only, is a commonly held view among Hungarian citizens (Reference Mewes, Mau and Svallfors2012, p. 136). Their research shows that approximately 10% of Hungarian citizens can be considered to have welfare chauvinist attitudes. In another study, Mewes and Mau (Reference Mewes and Mau2013, p. 236) find that Hungarian citizens also display the lowest willingness to grant immigrants unconditional access to welfare benefits, using European Social Survey Data from 2008 to 2009 and 26 European countries. In contrast, the share of Hungarians in favour of granting welfare benefits exclusively based on citizenship was the third highest among all countries included in the study at 51.2%. Given these numbers, there is surprisingly little research on the exploitation and shaping of the demand for welfare chauvinism by political parties in Hungary, a most-likely case. Assuming parties to be rational actors, they should be very likely to explore the high demand for welfare chauvinist policies as in Hungary. Consequently, Hungary represents an interesting case to study the framing of these issues, also because it complements a field that has mainly focused on Western European cases (see for example, Reference Nordensvard and KetolaNordensvard & Ketola, 2015; Reference NorocelNorocel, 2016). Examining a CEE case also engages unresolved debates about differences between Eastern and Western Europe welfare state regimes sparked by Esping-Andersen's influential typology work on liberal, corporatist, and social democratic welfare regimes (Reference Anderson1991). In response to critique that the post-communist experience qualifies as a different case, Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen and Esping-Andersen1996) and others, such as Deacon (Reference Deacon1993), insist divergence from Western Europe is temporary, given that these nations are in transition. Others assert that in spite of transition, the strength of the communist legacy places these nations on a path-dependent track (Reference FengerFenger, 2007, p. 3). Testing this thesis, Fenger's findings support a distinct welfare state regime that can be further divided into three subgroups (Reference Fenger2007, p. 22). Further, it is important to note that welfare chauvinism may not be directed only towards immigrants, but may also be used to define ethnic minorities that live in a country as less deserving of social benefits, as Rydgren points out (Reference Rydgren2007, p. 245), a question that has not been addressed extensively thus far. Finally, the rich data should allow an exploration of if and how we can distinguish between populist and nationalist frames.

3.2. The PRR in Hungary

As a party family, there are many commonalities within the PRR, but there are also important differences between Western and Eastern Europe (Reference AllenAllen, 2015). This is partly because Communist Europe did not experience the many social changes, including immigration, in the 1980s that shaped the development of the Western European far right (Reference BornschierBornschier, 2010). The experiences of communism and the painful transition to market economy and democracy dramatically shaped party competition in Eastern Europe (Reference Bustikova and KitscheltBustikova & Kitschelt, 2009). During the transition, parties grappled with the same valence issues such as the market, EU accession, public spending, budgets, etc. Along with technocracy, parties adopted strategies of nationalism and populism to successfully compete (Grzymalała-Busse & Innes, Reference Grzymalała-Busse and Innes2003, pp. 66–67). Populist parties in East Europe also present themselves as leaders of a social movement (Reference Gunther and DiamondGunther & Diamond, 2003), with a strong emphasis on historical legacies, conditioned by the particularities of the post-communist transition to democracy and eventual EU membership (Reference PirroPirro, 2014). Another feature of the PRR in the East is the prominent role of Christianity in political rhetoric (Reference FroeseFroese, 2004). In Western Europe, populism tends to occur on the fringes of the party system, whereas in CEE, populism is a more mainstream occurrence (Kopecký & Mudde, Reference Kopecký and Mudde2002). Hungary is not an exception. Populism and nationalism have always been a feature of Hungary's post-communist government, in part because of late regime change compared to other countries that transitioned earlier in the democratisation wave of the 1960s and 1970s (Ágh, Reference Ágh1998, p. 67). As with other CEE countries, strong narratives of the past, or historical legacies, often underpin these rhetorical strategies and discourses (Reference PirroPirro, 2014). For example, one of the most contentious policy areas concerns the Hungarian diaspora living as minorities in neighbouring countries. The nationalist – cosmopolitan liberal divide was as prominent as the communist legacy and this polarised political climate opened space for parties to adopt populist strategies (Reference EnyediEnyedi, 2016a, pp. 4–6). Hungary also stands out among CEE countries as the cultural versus economic divide has been a defining feature since transition (Casal Bértoa, Reference Casal Bértoa2014; Reference Enyedi, Katz and CrottyEnyedi, 2006; Kitschelt, Mansfeldova, Markowski, & Tóka, Reference Kitschelt, Mansfeldova, Markowski and Tóka1999; Körösényi, Reference Körösényi1999). Hungary also presents an extreme case among CEE peers, which Enyedi (Reference Enyedi2016a) characterises as ‘populist polarisation’ in which the entire party system is dominated by PRR politics. Fidesz is the governing party led by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, in power since 2010. Jobbik, led by Gábor Vona, is the official opposition party and has been characterised as an extreme populist radical right party. Pirro notes that right-wing populist actors increasingly engage socio-economic issues into their platforms and these are often manifested through (exclusionary) nativist discourses. An unintended consequence of such party competition is that Fidesz’ adoption of Jobbik's positions lends credibility to ideas of the populist radical right that were previously viewed as unrealistic (Reference PirroPirro, 2016, pp. 355–356). The two parties are coming to resemble each other, with Fidesz adopting more extreme positions and Jobbik taking on a more nuanced approach (Reference PirroPirro, 2016, p. 353). These observations support assertions that Fidesz and Jobbik are in many ways ‘twin parties’ competing for many of the same voters. The biggest challenge for Fidesz is to discern the party from Jobbik while trying to monopolise the extreme vote (Ágh, Reference Ágh2014, p. 45).

3.3. Social policy in Hungary

Following the 2008 Financial Crisis, Hungary's social policy laws have changed dramatically, taking on a ‘neo-liberal, étatist and neo-conservative’ shape (Reference SzikraSzikra, 2014, p. 488). This process has been accelerated by the election of the conservative government coalition in the 2010 Hungarian elections, led by Victor Orbán's party Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Union and the Christian Democratic People's Party (KDNP). For instance, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data shows that overall social spending in Hungary lowered from 23% of GDP in 2010 to 20.6% in 2016 (OECD, 2016). In addition to lowered spending, three changes stand out. First, pension schemes were reformed such that formerly private pillars were nationalised and social insurance rights cut. Notable changes include increased retirement age, reduced payments, and of consequence for the disabled, limited access to invalidity pensions (Reference HermannHermann, 2017, p. 55). Second, a new unemployment system was put in place to curb particularly the rights of the unemployed and to replace activation policies with a compulsory public work programme. Finally, new family policies that instated a flat tax of 16% paired with tax credits resulted in reverse distribution from poor to rich families by benefitting middle to higher income families (Reference SzikraSzikra, 2014, p. 488). These reforms are concerning for single parent families, as this group represents the highest risk of poverty and social exclusion in Europe (Eurostat, 2016). Further, these policy changes not only affect the poor in general, but especially the Roma living in Hungary leading to an increasingly ‘ethnic face’ of welfare policy (Reference SzikraSzikra, 2014, p. 496; Reference InnesInnes, 2015).Footnote 4

Another notable observation in the post-Financial Crisis period is, that Jobbik, as the main competition of Fidesz for voters, managed to dictate the government's economic direction at least to some extent (Reference PirroPirro, 2016, p. 355). However, while the government coalition Fidesz-KDNP has mainly focused on neo-liberal policies with consequences for the Roma, Jobbik has emphasised a leftist national economic programme according to which any foreign investments and business, i.e. ‘nonnative’ business and market capitalism would not be able to fulfil ‘the interests and needs of Hungary and its native population’ (Reference PirroPirro, 2016, p. 355). In sum, both PRRs Fidesz and Jobbik have left their mark on Hungary's social policies over the last years. For these reasons, this paper focuses on how both of these parties have articulated and framed social policies and social policy issues. This is important because, as Pirro (Reference Pirro2016) points out, in spite of dramatic policy changes, political polarisation, and a spike in PRR party politics, very little is written about PRR parties and their economic programmes and social policies in Hungary.

4. Research strategy

To answer my research questions, I mainly focus on party manifestos of Fidesz and Jobbik from the 2010 and 2014 elections. One disadvantage of using manifestos is that they are generally produced prior to an actual election campaign. Thus, they cannot capture all the issues and dynamics during an actual election campaign. However, various studies show that parties generally tend to follow their manifestos when transforming pledges into actual policy outcomes (Reference NaurinNaurin, 2014; Reference RoyedRoyed, 1996; Schermann & Ennser-Jedenastik, Reference Schermann and Ennser-Jedenastik2014; Reference ThomsonThomson, 2001). Thus, manifestos are key documents because of their implications for policy-making (Reference Ennser-JedenastikEnnser-Jedenastik, 2018, p. 301). To supplement and overcome the shortages of manifestos, I also include Annual State of the Nation speeches for 2016 and 2017. High profile political speeches, such as the State of the Nation, which is printed, televised, and cited within media, are useful for seeing what the electorate is exposed to. Thus, they are a logical place to look for elite discourse as they provide a key outlet for political elites to communicate with the public they serve. Many people outside of law, politics, or academia may not have an expert understanding of the some of the issues, as they are complex. Speeches and campaigns are highly visible, widely covered sources of information and for many, the only source of information about certain issues. While the focus of this paper is the Post-Financial Crisis era from 2008 onwards, I also included both parties’ Founding Charters, from 2007 for Fidesz and 2003 for Jobbik, to offer a snapshot of how these parties have engaged welfare issues right from the start. Methodologically, I apply a critical frame analysis as a way to interpret the social policy discourses of Fidesz and Jobbik. Following van Hulst & Yanow (Reference van Hulst and Yanow2016), I discern between frames and framing. Frames tell us what an issue is about (Reference Gamson and ModiglianiGamson & Modigliani, 1987, p. 143) and offer stories and narratives to help interpret and legitimate issues, policies, and events (Reference Gamson, Klandermans, Kriesi and TarrowGamson, 1988, p. 219). As Pytlas (Reference Pytlas2015) reminds us, when studying frames it is important to distinguish between the frame and the issue being framed. The concept of framing indicates the ongoing process of discourse techniques to create frames (Reference van Hulst and Yanowvan Hulst & Yanow, 2016). Fairhurst & Sarr Reference Fairhurst and Sarr(1996) note that framing techniques include inter alia the use of metaphors, stories (including myths) and narratives, contrasting, and spinning concepts in a fashion that overtly or covertly inspire normative value judgments. The framing process involves identifying the problem, proposing solutions, and assigning blame and/or responsibly (Rein & Schön, Reference Rein, Schön and Weiss1977). From social movement theory, framing is understood to help set the policy agenda, thereby having a performative function. Similar to Rein and Schön (Reference Rein, Schön and Weiss1977), Snow and Benford, (Reference Snow and Benford1988), refine the concept and identify the three core tasks of framing as: diagnostic framing (pinpointing a problem and assigning blame), prognostic framing (presenting solutions), and motivational framing (directly linked to justifying action).

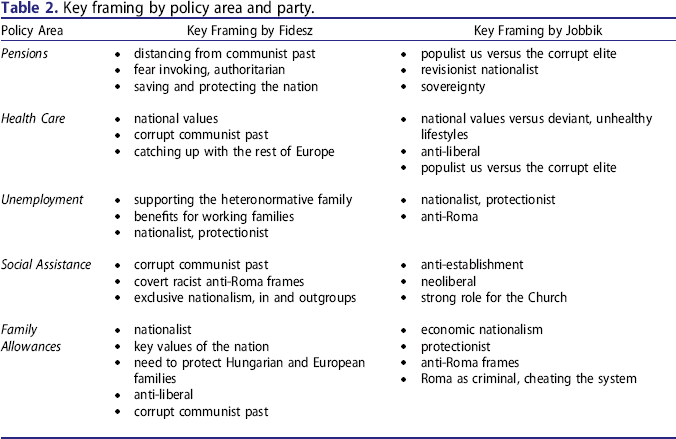

The texts are closely analyzed with attention to how the parties are framing the issues and with what strategies and rhetorical devices. As a method that places utmost concern on context, this approach is also particularly suited to distinguish between populist and nationalist frames. Further to that point, I adopt a reliable coding scheme from Caiani and Kröll (Reference Caiani and Kröll2017, p. 4) to aid with this distinction, see Table 1.

To further structure the analysis thematically, I follow Ennser-Jedenastik (Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2018) to focus on five social policy areas: pensions, health care, unemployment, social assistance, and family allowances.

5. Discussion of findings

In this section the social policies of Fidesz and Jobbik are presented by policy area. Figure 1 provides a brief overview of how much emphasise both parties place on the different policy areas. In the subsequent analyses, the party position on each policy area is briefly described and nationalist and populist references are pointed out and discussed. The purpose is not to detail each policy exhaustively but rather, to highlight how these parties frame these issues.

Figure 1. Word references to policy areas by party.

Note: Word references in all ten analyzed documents. Total word references Fidesz = 449. Total word references Jobbik = 246.

5.1. Pensions

In the 2010 manifesto, Fidesz notes how cuts to police pensions have devastated the number of officers in the force, some due to retirement but nearly 8000 left due to poor salaries and pensions. The situation is dire and at least 3000 more officers are needed to perform basic duties (Fidesz, 2010, p. 55). Put this way, there is a sense of urgency for pension reform and without it, law and order will be difficult to maintain. The need for protection takes on a fear-invoking authoritarian tone. Every society is responsible for the elderly, and the socialist-liberal government of the past eight years did a poor job of taking care of the retired (Fidesz, 2010, p. 77). This statement justifies change and in particular, rightist conservative changes by pointing out failures of the previous government. Within the CEE context, a critique of the socialist left is unsurprising given the link to the communist history with post-communist parties struggling to move away from the past (Reference Bozoki and IshiyamaBozoki & Ishiyama, 2002, pp. 6–7). The 2016 State of the Nation Speech by Orbán is largely self-congratulatory, taking stock of successful reforms taken thus far, spinning Fidesz policies as saving and protecting the nation. For example, Orbán remarks,

We have protected pensions and pensioners, and have gone the extra mile in supporting families. We have restored public order and the self-esteem of the police, and have also created a counter-terrorism and disaster management system. We have rescued our schools and hospitals (Reference Orbán2016, §9).

Right from the Founding Charter, Jobbik positions itself as the leader of social movement to expel ‘ … Successors of the Communist party and the extremist liberals, who are inextricably entwined with them, from the political power’ to represent the entire nation (2003, p. 2). Jobbik appeals to ‘the people’ who are underrepresented and suffering from low wages and pensions (2003, p. 2). This reference to ‘the common people’ fits squarely within populist discourse. The 2010 Manifesto adopts a more nationalist tone. Jobbik outlined its vision for total reform, ‘a genuine policy for the whole nation’ that is, ‘In short, the return of national autonomy. In a word: a brighter future!’ (Jobbik 2010a, p. 1; Jobbik, 2010b). The ambitious reforms of the pension system include age allowance, increased funds for seniors, and review ‘disproportionately high pensions originating as rewards for service to the single-party state’ (2010, p. 4). The latter point not-so-subtly references the communist era suggesting the system is still corrupt. References to the communist era also lend support to Fenger's (Reference Fenger2007) ideas about path-dependency shaping contemporary welfare politics. Jobbik also clarifies that while Hungary is responsible for the Hungarian diaspora in neighbouring countries, those that obtain dual citizenship are not automatically entitled to benefits without residency (2010, p. 15). Jobbik has always campaigned on a revisionist nationalist platform that makes appeals to the ‘wider Hungarian nation’, stirring up memories of the Treaty of Trianon that reshaped Hungary's borders in 1920Footnote 5 (Reference PytlasPytlas, 2013, p. 163). The 2016 and 2017 State of the Nation Speeches by Vona are no exception and reiterate the importance of the pension system (Reference VonaVona, 2016; Reference VonaVona, 2017).

5.2. Health care

From the Founding Charter, Fidesz (2007) asserts that health care policy is a priority. The 2010 manifesto links policy to national values in stating, ‘Thus you can find the policy back to everyday life and the people, the values connecting us all: work, home, family, health and order is placed in the centre’ (p. 21). A key goal for health care in Hungary is to ‘catch up’ with Western European countries (2010, p. 45). The Manifesto goes on to outline how the socialist-liberal government of the last eight years is responsible for seriously mismanaging funds leading to the current disarray of the bankrupt and near-bankrupt hospitals, poor patient care, and overall degradation of all health care infrastructure (2010, p. 63). Use of this ‘corrupt communist’ frame is in line with CEE party discourse dealing with legacies of the past, as seen above in Fidesz’ rhetoric on pensions. The previous socialist government is also blamed for the ‘brain drain’ of Hungarian doctors and nurses migrating in search of better employment opportunities (2010, p. 69). Fidesz further points to the state of the Roma, noting that the drastically dismal education and employment conditions impact health in a negative way and that the only appropriate policy response is to stop ‘scapegoating’ (2010, p. 83). This message is a covert shot at Jobbik whose surprising electoral successFootnote 6 as a PRR party has been linked to their extreme anti-Roma stances (Karácsony & Róna, Reference Karácsony and Róna2011). The 2016 State of the Nation praises the responsible reallocation of funds to improve the health care system with a nod to the hard work of teachers and health care workers (§ 9).

Jobbik calls for action in the Founding Charter when they note, ‘We cannot accept the tragic demographic situation, the mental and health condition or self-destruction of the Hungarian society! Political parties remain idle and silent even though the existing unresolved issues demand action!’ (2003, p. 1). As Gunther and Diamond (Reference Gunther and Diamond2003) point out, Eastern PPR parties are more likely to present their appeals as leaders of a social movement and the above quote lends credence to this thesis. In the populist framing of tragedy and self-destruction, Jobbik also blames the other parties for the status quo. The 2010 manifesto calls for all-encompassing social reform to promote, ‘a genuine policy for the whole nation; and a youth programme designed to promote national wellbeing’ (2010, p. 4). They call for an end to widespread and deeply entrenched corruption, a typical populist frame of the ‘corrupt elite’. Jobbik partly blames the poor state of health and lowering population as compared with other European nations on a ‘growth of unhealthy lifestyles’ and insists that, ‘This population crisis has been exacerbated by the destructive behaviour of the political establishment’ (2010, p. 9). For Jobbik, the solution is through a traditional family policy that does not support an ‘alternative living arrangement or deviant lifestyle’ (2010, p. 9). This framing blames liberal values as responsible for health and population problems. While not saying it directly, this position attacks gender and sexual orientations that do not fit within conservative hetero-normative constructions of the family, positioning single mothers/fathers and the LGBT communities as ‘others’ outside the national norm. In a study on the relationship between gender roles and populism in Austria, Mayer et al. (Reference Mayer, Ajanovic and Sauer2014) reached similar conclusions. In the face of high abortion rates in Hungary, Jobbik's policies on regulating the family go further when they express interest on abortion policy that is acceptable for the medical and Christian communities (Jobbik 2010a, p. 12; Jobbik 2010b). The 2014 manifesto frames health issues through nationalist arguments. As said by Jobbik, ‘The health problems of the Hungarian nation are mostly rooted in mental-spiritual reasons. A nation that does not feel good, that has been mutilated, invaded, oppressed, whose wish for freedom is suppressed, and which is misled will sooner or later show physical deterioration as well’ (Jobbik, 2014a, pp. 23-24; Jobbik, 2014b).

5.3. Unemployment

In the Founding Charter, Fidesz proposes the New Széchenyi Plan aimed at cutting taxes for employers, creating programmes that encourage new job creation, and support part-time employment. Regarding part-time work, Fidesz believes that, ‘With the encouragement of part-time employment, we intend to provide employment primarily to women, young mothers, people with disabilities, and students in higher education’ (2007, pp. 33–34). Szikra points out that such programmes benefit the wealthy more than those most in need (Reference Szikra2014, p. 488). Fidesz exposes its conservative agenda further with policies aimed at reforming the labour market toward more family-friendly employment (2010, pp. 74–75). The purpose behind such reforms is to promote the hetero-normative family having more children to raise the population. Regarding the Roma, Hungary's most disadvantaged and persecuted minority, the 2010 Manifesto nods to the desperate situation and that work options should be in place (2010, p. 82). In the 2017 State of the Nation, Orbán's messages about employment are shrouded in protectionist economic nationalist frames. For example, he warns against bringing in cheap labour as done in Western countries so that jobs can be kept to Hungarians and the country can be run by Hungarians (Reference Orbán2017, §9). Orbán also warns,

We must prepare for Brussels attacking our job creation subsidies. Many countries, including Hungary, use this simple tool of economic development. So the question is this: should nations be able to decide whether they want to give employers incentives to create jobs, or should this right also be transferred to Brussels? (2017, §15).

A first look at the above statement may easily be mistaken for a populist frame with the signifier ‘Brussels’ interpreted as the elite. However, a closer look reveals that ‘Brussels attacking our. … ’ fits within the nationalist frame of an attack on sovereignty, as illustrated above in Table 2, point 6. To support this idea further, Orbán then asserts that this attack amounts to no less than, ‘nations against globalists’ and that the Hungarian people must take charge of decision-making rather than transferring power elsewhere (Reference Orbán2017, §3), again insinuating that national sovereignty is at stake.

Like Fidesz, Jobbik promotes strong employment conditions for mothers to break down barriers between working and child rearing (2010, p. 9). Also similar to Fidesz, Jobbik espouses protectionist economic nationalist discourses against European Union employment directives, which demand close inspection (2010, p. 11). Their position on unemployment benefits is clear: work should be offered in place of cheques to cull the system of users and abusers. As said in the Manifesto,

Those capable of labour, should only be entitled to receive state support, through the completion of some form of work. With the nationwide introduction of a ‘Social Card’ scheme: we shall provide those individuals and families living under difficult circumstances, who both genuinely wish to improve their prospects and possess the willingness to accept employment when it is offered to them, with every possible opportunity for improving their living conditions; in addition to this such a Social Card scheme would bring to an end the epidemic of criminal usury [loan-sharking] that exists amongst those on welfare in Hungary (2010, p. 10).

At a glance, such criminalisation of the poor seems to be a blanket policy for all Hungarians drawing welfare benefits. However, by all social indicators, the Roma represent the most disadvantaged group in Hungary with an embarrassingly low employment rate of about 20% for Roma men and only 10% for Roma women totalling an unemployment rate of about 70% (ECRI, 2015, p. 26). This bleak situation is exacerbated by racism. The Council of Europe reports that, ‘Concerning employment, direct and indirect discrimination prevents a great portion of the Roma population from breaking the vicious circle of poverty in which they are caught’ (16 Dec. 2014, p. 27). So while Jobbik's remarks about the ‘Social Card’ do not single out the Roma explicitly, it is clear they are the targets of this policy as they over-represent the unemployed. There are other sections of Jobbik's employment stance regarding the Roma that are overtly hostile in both the 2010 and the 2014 Manifestos. For example, the 2010 Manifesto states that, ‘At the present time a segment of the Gypsy community strive for neither integration, nor employment, nor education; and wish only that society maintain them through the unconditional provision of state benefits’ (2010, p. 11). The solution to such poaching off the system, according to Jobbik, is to introduce workfare style benefits where anyone able to work must accept offered employment to receive public welfare benefits (2010, p. 12). The 2014 Manifesto carries on the workfare theme insisting that following job creation schemes, no-one unemployed could use excuses such as, ‘I would work but there are no jobs’ (2014, p. 20). While in principle, the workfare scheme sounds fair, it ignores race and ethnicity based obstacles people face.

5.4. Social assistance

In the Founding Charter, Fidesz states that the party's overall vision is a state with increased welfare benefits, strong employment rates, and Hungary as an economic leader within CEE (2007, p. 26). Later in the 2010 Manifesto, Fidesz lays blame on the social assistance programme for the ongoing poverty in the country. Low motivation has been culturally ingrained, keeping people out of the workforce and this legacy comes from the previous socialist government of the past eight years (2010, p. 26). This neoliberal approach to justify cutting benefits is typical of rightist parties (Reference McGann and KitscheltMcGann & Kitschelt, 1995). Against the painful backdrop of the communist past, Fidesz, from the conservative right, is also distancing itself from socialism while discrediting the left at the same time. Another example of such distancing is Fidesz’ promotion of a return to strong working families, which represents a common national cause, and disruptions over the past eight years (the previous socialist government) must be amended to secure the future for everyone (2010, p. 72).

Fidesz goes on to insist that criminal behaviour is an unacceptable response to poverty and will not be tolerated. Membership within Hungarian society is only for law-abiding citizens who earn an honest living through legitimate employment (2010, p. 52). Although Fidesz does not single out the Roma directly, the link between poverty and criminality evokes widespread public discourse frames. For instance, the ECRI (2015) points out a court case where the presiding judge drew on stereotypes of ‘Gypsy crime’ (most widely used by Jobbik) and the ‘Roma lifestyle’, which stands in opposition to national norms and is characterised by avoiding work (2015, p. 16). These covert racialized remarks by Fidesz about the unemployed and the criminal represent exclusive-nationalist discourse of in and out groups, the Roma falling into the latter category. The party later cites equal opportunity as a common value (2010, p. 73). The colour-blind approach to policy can be problematic. Kirkham (Reference Kirkham and Satzewich1998) points out that rightist discourse is often articulated through frames of equality and rights. The trouble with such a colour-blind approach to equal opportunities is that the roots and very real barriers of racism remain unaddressed (Reference Delgado and StefancicDelgado & Stefancic, 2017).

Jobbik has not been as vocal as Fidesz on issues of social assistance specifically, save for some chiefly nationalist remarks in their 2010 Manifesto. Jobbik's position on social assistance begins with populist rhetoric, blaming declining birth rates on the ‘destructive behaviour of the political establishment’ (2010, p. 9). Making arguments rooted in nationalist discourse, the party maintains that in order for the nation to grow, Jobbik plans to enact a ‘coherent family and social policy’, namely the hetero-normative family (discussed further below) (2010, p. 9). Jobbik's position on social welfare stresses the importance of Christianity while also adopting elements of neoliberalism, such as assigning responsibility for well being on the individual, the family, and all other resources before turning to the state for assistance. The social responsibility of the state is to support homebuilding, conditional benefits, and assistance for the disabled and the homeless (2010, p, 10). The party clarifies that state responsibility is not all encompassing and unconditional, rather state responsibility is limited to supporting institutions such as ‘municipalities, established churches and nongovernmental organisations’ (2010, p. 10). Jobbik's support of the Church as an important institution responsible for social welfare further establishes the role of the Church in national policy. The primacy of Christianity is typical of PRR discourse in CEE (Reference FroeseFroese, 2004).

5.5. Family allowances

Right from the Founding Charter, Fidesz states plans for family tax reform based on income and number of children (2007, p. 36). Much the 2010 Manifesto emphasis on the family is presented through a nationalist lens. For example, work, home, the family, health, and order are all cited as the key values of the nation (2010, p. 21). According to Fidesz, the family is central to Hungary and Europe and must be protected to preserve Hungarian and European mental and spiritual health (2010, p. 24). Reforms are necessary to make the labour market more family friendly, including child care options, and non-traditional work such as part-time employment for families with young children (2010, p. 75). For Fidesz, working families contribute to national prosperity so policy should be directed there (2010, p. 76). Family directed policy sounds noble, however Szikra argues that Fidesz’ reforms that privilege better off families in tandem with cuts to unemployment assistance have actually increased social polarisation and poverty levels (Reference Szikra2014, p. 495). As in the above discussion on unemployment, the Roma represent the most impoverished group in Hungary with staggering unemployment numbers in the range of 70%. Without confronting racial barriers that Roma face, employment based benefits is not likely to foster meaningful change for this group. Szikra's (Reference Szikra2014) observations on the increased poverty gap confirm this.

Viktor Orbán's, Reference Orbán2014 Speech directly attacks liberalism and takes on a strong populist tone. According to Orbán,

It is always the stronger neighbour who decides where the driveway will be; it is always the stronger party, the bank, who decides the interest rate on mortgages, and who changes it mid-term if needed, and I could continue on with a long list of instances that individuals and families with weaker economic defences experienced regularly during the previous twenty years. It is in reply to this that we suggest, and are attempting to construct Hungarian state life around this idea, that this should not be the principle on which society is built (Reference Orbán2014, §10).

In this narrative, it is always elites making decisions for Hungarians and not the people making decisions for themselves and this needs to stop. Orbán goes to say that liberalism has failed the people in many ways, including,

The liberal Hungarian state was also incapable of protecting the country from falling into debt. And finally, it did not protect the country's families, and I mean the system of foreign currency loans in this instance. It also failed to prevent families from falling into debt slavery (Reference Orbán2014, §11).

This is yet another example of this party, or in this case the party leader, ascribing blame for poverty among Hungarian families elsewhere. Earlier at the beginning of Fidesz’ rule, the culprit for the poor state health care and family impoverishment was the ghost of the communist past and now after four years in power, Fidesz blames liberal values, espoused mainly by the European Union and the United States.

Much of Jobbik's position on the family are tied into other policy areas such as employment and health care, as discussed earlier. Specific policy aimed at family allowances is focused on housing and regulating the Roma. The 2010 Manifesto proposes an economic nationalist homebuilding programme to protect the, ‘Tens of thousands of Hungarian families [that] have ended up the victims of both foreign banks, and foreign construction companies, due to financing drawn on currencies such as the Swiss Franc, the Euro, and the Yen’ (2010a, p. 10). What is needed is a national homebuilding programme aimed at more family houses (2010a, p. 10). The home building programme would be for all working Hungarian families, or those willing to take employment (2014a, p. 11). This represents an example of a citizenship argument that dictates what the ideal family looks like.

As with the aforementioned ‘Social Card’ scheme, family allowances for the Roma would be restricted as well. Jobbik states,

In the interests of restricting the regrettable practise of the bearing of children for the purposes of economic subsistence through the state benefits receivable: child benefit will be reformed nationally, so as to only be receivable after the third child, in the form of tax relief; and it is vital that all child benefits be conditional on that child's attendance in education (2010, p. 12).

This direct attack on the Roma plays on stereotypes of Roma families having many children to collect more welfare benefits. Jobbik's position on this is reiterated later in the document with a bullet point list that also calls for the need to ‘Cleanse Gypsy political life from confidence tricksters, criminals and other impostors who make a living off being a Gypsy’ and that ‘Gypsy crime must be eliminated’ (2014, p. 19). The not-so-subtle implication of framing the Roma community as corrupt criminals negates their deservingness of state benefits, as the community should be regarded with suspicion rather than sympathy.

5.6. In sum

The rise of the radical right in recent years has changed the social policy landscape in Hungary. Aside from reforms and cutbacks to social spending, the radical right has also brought changes to political discourse apparent in the renaming of policies. As Lendvai-Bainton puts it, ‘Many of the former social benefits were renamed in a way that ‘social’ becomes eradicated and replaced with either employment or parish related terminologies’ (Reference Lendvai-Bainton, Kennett and Lendvai-Bainton2017, pp. 408–409). Some examples she notes include changing social assistance to parish assistance, gender mainstreaming to family mainstreaming, and unemployment benefits to job seeker support (Table 24.1, p. 409). The way social policy issues are framed by Hungary's Radical Right resembles typical back and forth party competition in CEE. Both Jobbik and Fidesz employ frames of the corrupt communist past when identifying what the issue is about and who is to blame (diagnostic framing). While this approach to framing the issues can be interpreted as populist discourse because it blames former elites, i.e. former socialist communist-successor parties, for the issues, it differs from the Radical Right in Western Europe precisely because of the post-communist background in which the blame-game takes place. The backward glances to the communist era also suggest enduring legacy impacts. This fits with Fenger (Reference Fenger2007) findings on a fourth welfare state regime that is distinct from Western Europe. Another observation was that, essentially, Fidesz and Jobbik employ similar framing strategies on social policy to compete for similar voters.Footnote 7 This lines up with Pytlas’ conclusions of high congruence on policy positions between the two parties leading to increased party competition over ownership of salient issue frames (Reference Pytlas2015, p. 138). Among both parties, this paper found a strong emphasis on anti-Roma frames. This does not come as a surprise, given Jobbik's ownership of the ‘Gypsy crime’ frame, in large part responsible for the party's rapid electoral success. There were, however, nuances that are worth pointing out and these go beyond Fidesz’ neo-liberal approach as opposed to Jobbik's more socialist interpretation of social issues. While Jobbik appeared to present itself as leader of a social movement, Fidesz put strong a strong authoritarian focus on order along with continuously highlighting the importance of Christian values as the fundamental basis for an ordered Hungarian society. Finally, while Jobbik's discourse showed strong traces of overt racism, Fidesz was much more covert in that respect, yet just as dangerous, an observation others have made before (cf. Mudde, Reference Mudde2015).

An observation made beyond the paper's original goal to identify and distinguish between populist and nationalist frames was the role of gender, an issue that so far has received far less attention from scholars working specifically on the radical right (but see Spierings, Zaslove, Mügge, & de Lange, Reference Spierings, Zaslove, Mügge and de Lange2015; and Félix, Reference Félix2015 for notable exceptions). Elsewhere, scholars note that it no longer makes sense to view the nation-state as neutral regarding gender (see Reference ConnellConnell, 1990; Reference McClintockMcClintock, 1995; Reference Pateman, Pierson and CastlesPateman, 2000; Reference Yuval-DavisYuval-Davis, 1993), sexuality (see Reference MosseMosse, 1985; Reference PetersonPeterson, 1999) or race (see Reference Goldberg, Goldberg and SolomosGoldberg, 2002) but as an active mediator that (re)produces, exacerbates, and regulates these differences. The performative role of the nation-state on gender is particularly salient within national borders, and within discursive and policy constructions of ‘the nation’ (Reference Abu-LabanAbu-Laban, 2009). Both PRRs in Hungary, but especially Fidesz, clearly define the role of women in their vision for Hungary and the ideal Hungarian family. Fidesz has even enshrined ‘the family’ as a marriage between a man and woman into the Fourth Ammendment of the Fundamental Law of Hungary (the new constitution revamped under the Fidesz government) (Reference SzikraSzikra, 2014, p. 494). Because these parties again and again emphasise how Hungary should become an ‘anti-liberal’ state (Orbán, Reference Orbán2014), women, as the backbone of Hungarian families, should stay at home to produce enough children to form a strong, Hungarian nation.

6. Concluding remarks

This paper set out to investigate how PRRs in contemporary Hungary frame social policy issues. The main proposition advanced in this research was that these issues would be framed in strong nationalist and populist frames. The emphasis, however, was not only in identifying these framing strategies but also to make the distinction between nationalism and populism in line with recent attempts to establish clear theoretical differences between the two (Reference De Cleen, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and OstiguyDe Cleen, 2017; De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Reference De Cleen and Stavrakakis2017). In separating social policy issues along five different dimensions, namely pensions, health care, unemployment, social assistance, and family allowances, I detected that Hungary's contemporary radical right employs mostly nationalist framing. Although populist framing was evident on some occasions, it was mostly informed by a nationalist worldview. This lines up with Rydgren's (Reference Rydgren2017) recent argument that essentially, most PRRs are not so much a populist party family. Rather, they do employ populist discourse from time to time but it is informed by their nationalist views. This is not to say that populism does not play a role. However, we may be best served in using it, as Rydgren (Reference Rydgren2017, p. 9) puts it, as an ‘additional qualifier’. In some occasions, however, the academic love affair with labelling all rightist parties populist is akin to being in a toxic relationship; it serves no good but is difficult to walk away from. Future research on the differences between nationalism and populism will tell just how much the latter can help us advance our understanding of radical right parties.

Because this is one of the first studies to take the social policy issue into a CEE context, it is also worth discussing some of the main differences between the radical right in CEE and in Western Europe in terms of their approaches to social policy. First, while the early observations made here do not settle the debate on welfare state regimes (Reference Esping-AndersenEsping-Andersen, 1990, Reference Esping-Andersen and Esping-Andersen1996; Reference FengerFenger, 2007), they do reveal that legacy plays a role in articulating welfare policy and is worthy of further investigation. Second, many scholars find that PRRs in Western Europe made a sharp transition from neo-liberal to pro-welfare parties, restricting benefits to those they see as belonging to the nation (see De Lange, Reference De Lange2007). In Hungary one could argue, we see both. While both Jobbik and Fidesz both approve some measures of welfare benefits, Jobbik's socialist view differs in many aspects from the neo-liberal focus of Fidesz (Reference PirroPirro, 2016; Reference SzikraSzikra, 2014). Nonetheless, both manage to frame the issues in a nationalist way. Thus, the question arises whether a pro-welfare position is necessarily a feature of PRRs in all contexts. Lastly, another area that deserves attention for future research is the role of gender in the social policy discourse and, for that matter, in the literature on the PRR. As this work has shown, both PRRs in Hungary emphasised the role of the women as the foundation for a strong nation. This may serve as the basis for future investigations into other contexts to find out how gender fits within the nationalist narratives of PRRs.

While the current political and policy climate in Hungary does suggest a decline of the welfare state, it is difficult to characterise Fidesz’ approach to social policy as either welfare chauvinist (as research on the PRR and welfare chauvinism would suggest) or more neo-liberal as we see evidence of both. This observation lends purchase to Lendvai-Bainton's assertion that the economic policies of the radical right in Hungary are best understood as a hybrid ‘authoritarian neoliberalism’ which rejects some elements of democracy and with sometimes contradictory social policy marked by generosity in some areas with cutbacks in others (Reference Lendvai-Bainton, Kennett and Lendvai-Bainton2017). A striking example is family tax policy, marked by increased spending and benefits, but only for those who conform to Fidesz’ narrow definition of the family to the detriment of others. In terms of party strategy, Fidesz has proved to be particularly adept at appealing to voters across the far and centre right resulting in electoral success. In addition, the hybridity of welfare chauvinist and neoliberal approaches to policy in the name of protecting ‘the people’ and ‘the nation’ may appeal to voters across the right end of the spectrum. A grave consequence of Fidesz’ ongoing electoral success and both parties on the radical right sharing similar policy platforms is what scholars like Feischmidt and Hervik (Reference Feischmidt and Hervik2015) call a ‘mainstreaming of the extreme’, where nationalist and racialized frames normally of the far right move centre and become normalised in public and policy discourse. The trend of normalising, or mainstreaming, divisive politics paints a bleak picture for social inclusion and poverty reduction in Hungary.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.