Introduction

A substantial literature exists on how federalism affects the development of social policy in wealthy democracies (for an overview, see Reference Obinger, Castles, Leibfried, Obinger, Castles and LeibfriedObinger, Castles, & Leibfried, 2005). While the literature generally suggests that federalism inhibits growth of social policy, it suggests that a number of different impacts of federal arrangements are possible, ranging from ‘laboratories of democracy’ to a ‘race to the bottom’ and ‘collusive benchmarking’ (Reference Harrison and HarrisonHarrison, 2006). This paper addresses a key question arising from that literature: under what conditions is one of several possible federalism policy dynamics likely to be dominant in a particular sector or program? We explore this question with respect to the contributory, earnings-related pension tier of Canada's multi-tier pension system: the Canada Pension Plan (CPP), which operates outside of Quebec, and the Quebec Pension Plan (QPP), which operates only in that province. (Canada also has a quasi-universal flat-rate pension tier, known as Old Age Security, and an income-tested tier, called the Guaranteed Income Supplement, both run by the federal government and financed through general revenues; see Béland & Myles, Reference Béland, Myles, Bonoli and Shinkawa2005; Reference Myles, Banting and MylesMyles, 2013; Reference Prince, Doern and StoneyPrince, 2012, Reference Prince, Doern and Stoney2013).

Changes to the CPP require the agreement of at least seven provinces having two-thirds of the Canadian population, while Quebec can alter the QPP unilaterally. Since the creation of the two programs in the mid-1960s, their contribution and benefit structures have been closely integrated, and benefits are transferrable between the two programs. But growing differences in the long-term demographic and economic growth outlooks for Quebec and the Rest of Canada (ROC) have made it increasingly challenging to retain nearly-identical contribution and benefit structures for the CPP and QPP. The patterns observed in the evolution of the CPP/QPP arrangement can be understood by examining how, in a changing demographic, economic, and political context, the unique characteristics of the CPP/QPP have led to the dominance of different federalism policy dynamics – notably collusive benchmarking, joint decision traps, and race to the top dynamics – over time. After a brief discussion of the historical origins of the unusual parallel CPP/QPP arrangement, this article focuses on the evolution of the relationship between CPP and QPP benefit and payroll contribution structures over time. We argue that the recently-announced expansion of CPP is due in large part to a combination of collusive benchmarking and a race to the top dynamic created by a pension initiative in the province of Ontario that put pressure on the newly-elected federal Liberal government of Justin Trudeau to strike a deal with the provinces to bring about CPP reform. As for the QPP expansion announced in late 2017, it is directly related to a collusive benchmarking dynamic created by the previously-announced CPP expansion which, combined with internal political factors, paved the way for a QPP reform modelled on CPP reform.

Theoretical Perspectives on Convergence and Divergence in Pension Reform

As noted above, the rich literature on federalism suggests that several distinctive policy dynamics may evolve in federal systems (on the relationship between federalism and CPP/QPP, see Reference Banting and IsmaelBanting, 1985; Béland & Myles, Reference Béland and Myles2012). Different sub-national programs operating in parallel (usually at the provincial level, but in the CPP/QPP case, one federal and one provincial) may, for example, develop relatively independently based on the ‘internal determinants’ of the regions that put those programs into place. These determinants include public and elite opinion and fiscal capacity. Alternatively, the programs’ sponsoring governments may learn from the experience of other programs, a process that is sometimes termed ‘laboratories of democracy.’ The governments sponsoring these programs may also compete to offer the least generous programs (‘race to the bottom’) or the most effective ones (‘race to the top’). Kathryn Harrison (Reference Harrison and Harrison2006) adds that these governments may also engage in what might be called ‘collusive benchmarking’ to avoid the development of a competitive dynamic that forces them to shift away from the policy status quo toward less-preferred positions.

Given that several different policy dynamics may emerge in federal systems, it is clearly important to specify the specific conditions under which specific policy dynamics are more or less likely to emerge (Weaver, et al., Reference Weaver, Goodyear-Grant, Johnston, Kymlicka and MylesForthcoming). Several sets of underlying conditions are important, notably: (1) jurisdictional arrangements and decision rules; (2) programmatic fiscal demands and general fiscal slack; (3) the heterogeneity of sub-national units; and (4) issue salience and incentive effects for politicians. A ‘joint decision trap’ (Reference ScharpfScharpf, 1988, Reference Scharpf2006) is most likely to emerge when policies require super-majority approvals or multiple veto-point hurdles, especially in combination with very heterogeneous policy preferences on the part of the units that must approve any changes. Collusive benchmarking is most likely to emerge and be sustained when the number of sponsoring governments that must collude is relatively small, their preferences are fairly to very homogeneous, and when low issue salience means that their preferences are unlikely to be challenged by other actors.

Some of these parameters may be more susceptible to change over time than others. Jurisdictional arrangements and decision rules, for example, are usually relatively fixed, while fiscal slack, demographic realities, and political incentives are more likely to change. And as some of these parameters change, it may cause a shift from one policy dynamic to another: an increase in fiscal stress is likely to make a race to the bottom dynamic more likely, while a rise in issue salience may make it more difficult to maintain a collusive benchmarking strategy among the sponsoring government policy elites as interest group and electoral pressures gain force.

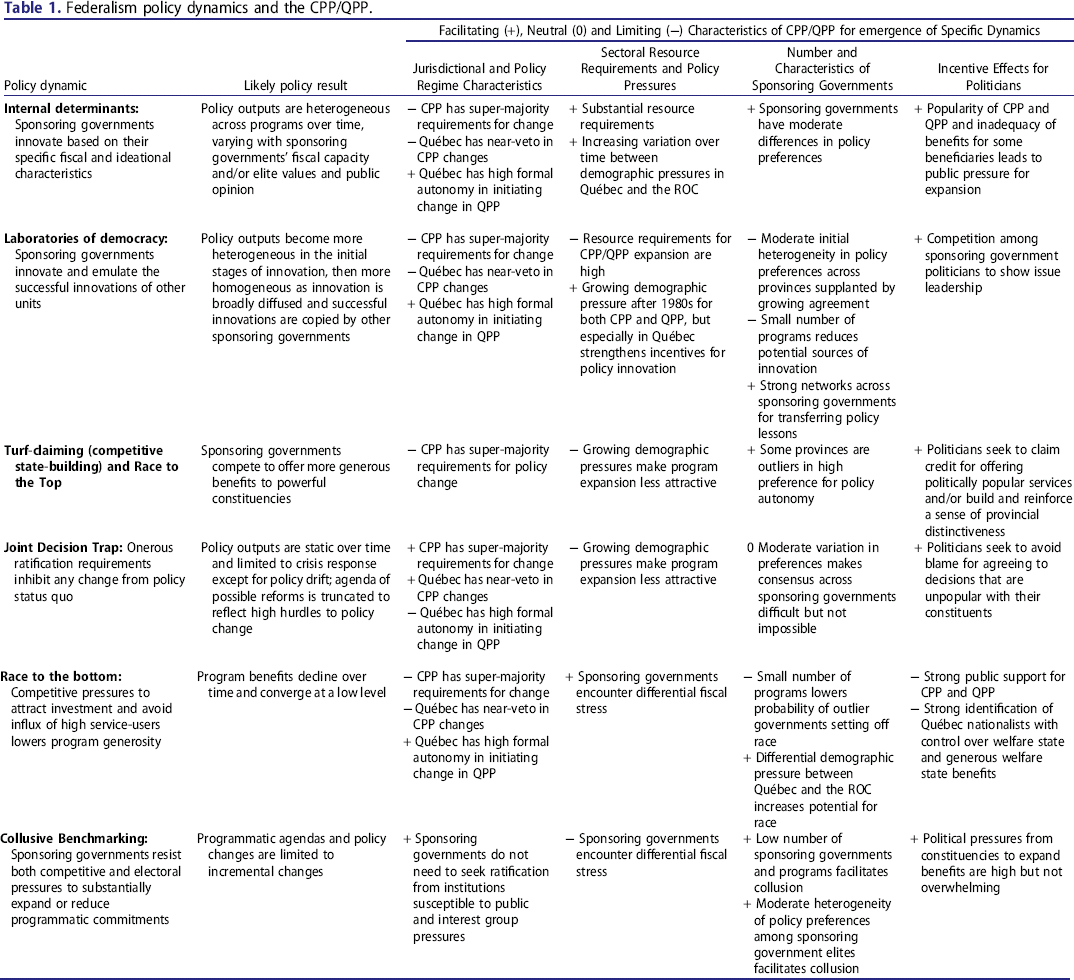

The federalism literature provides a useful starting point for thinking about factors underlying multiple policy dynamics, although these arguments have to be adapted to understand the factors that shape a policymaking system with ten provinces and a central government (henceforth, sponsoring governments) but only two programs operating in parallel (the CPP and QPP). Table 1 shows several different policy dynamics that may arise in federal regimes (left-hand column) and their likely effects on programs already in place (second column). The remaining columns show a number of conditions present in CPP–QPP policymaking that are likely to facilitate, inhibit, or are neutral toward the emergence of each specific policy dynamic, indicated by a +,– or 0, respectively.

As Table 1 shows, none of these dynamics is a perfect fit with CPP/QPP policymaking because the CPP/QPP conditions do not completely support any single dynamic with no undermining conditions. For example, the internal determinants’ dynamic suggests that differences in programs are likely to emerge across jurisdictions over time, reflecting differences in voters and elites’ policy preferences as well as differences in the fiscal capacity of the sponsoring governments of those different pension programs. The laboratories of democracy policy dynamic suggests that innovations in one program may spark learning that leads to the emulation of ‘best practices’ in other programs. Certainly, since the 1980s, growing demographic and fiscal pressure on both the CPP and QPP, but especially in Quebec, has strengthened incentives for policy innovation. But numerous factors, notably super-majority requirements for changes in the CPP, the fact that there is a program duopoly rather than many programs, and sponsoring governments’ wish to avoid bidding wars around CPP benefit levels, are likely to constrain policy dynamics driven both by internal determinants and laboratories of democracy. To the extent that these dynamics do emerge, as we will see later, they can be seen primarily with respect to particular mechanisms, most significantly, an independent investment board and automatic stabilizing mechanisms, rather than in major structural features of the two pension programs or their benefit levels. Similarly, competitive turf-claiming (especially on the part of the federal and Quebec governments) played an important role in the initial set-up of the parallel CPP and CPP. The super-majority requirements for changes in the CPP (including a near-veto for Quebec), moderate differences in policy preferences across sponsoring governments, and the desire of the policy elites governing both programs (particularly the federal and Quebec Ministries of Finance) to avoid getting into a bidding war in the expensive pension sector have tempered any move toward a race to the top in benefits since the CPP and QPP were in place, although this dynamic has not been entirely eliminated, especially during highly contested election campaigns.

Two policy dynamics that seem likely to occur much more persistently in the CPP/QPP relationship are a joint decision trap and collusive benchmarking. In the joint decision trap (see Reference ScharpfScharpf, 1988, Reference Scharpf2006), policy outputs are relatively static over time, except for policy drift (Reference HackerHacker, 2004). The list of possible reforms that appear on the policy agenda is truncated to reflect high hurdles to policy change, and policy changes are adopted only when a crisis makes change seem necessary. In collusive benchmarking, policy is not completely frozen; programmatic agendas and policy changes are limited to incremental changes through cooperative action between sponsoring governments so as to resist both competitive and electoral pressures to substantially expand or reduce programmatic commitments. The joint decision trap and collusive benchmarking policy dynamics are often difficult to distinguish in practice, and both are facilitated by jurisdictional arrangements that make changes from the status quo procedurally difficult. But collusive benchmarking suggests a higher degree of cooperation among policy elites to deal with common challenges, notably political pressures from the public to expand program benefits that are high but not overwhelming.

A policy dynamic that appears least likely to emerge in the case of the CPP and QPP are federal preemption and a race to the bottom. A race to the bottom policy dynamic that would lead to a reduction in program generosity over time is facilitated by fiscal stress and the differential actuarial pressures between Quebec and the ROC. However, the emergence of a race to the bottom in the CPP/QPP is made much less likely by many other factors, notably very strong public support for and the high salience of these programs, super-majority requirements for changes in the CPP, and strong pressures on Quebec elites to maintain QPP parity (or something close to it) with CPP benefits.

This approach has several implications for understanding the evolution of the CPP and QPP. First, a single political dynamic is unlikely to dominate all aspects of CPP/QPP decisions over time. Some combination of a joint decision trap and collusive benchmarking is likely to be seen persistently over time, while other dynamics such as a race to the top and laboratories of democracy are likely to occur only intermittently, and in a fairly muted form. Other dynamics, notably a race to the bottom, are likely to be seen rarely, if at all. Second, race to the top dynamics are possible when politicians put policy expansion onto the agenda. This is the case because expansion in one jurisdiction can put pressure on other jurisdictions to emulate it, especially when internal political factors reinforce the push for expansion within these jurisdictions.

CPP and QPP in historical perspective

The combination of universal and means-tested public pensions in place in Canada prior to the mid-1960s left most Canadian seniors with extremely inadequate pensions. The Liberal Party (in power in Ottawa from 1935 to 1957) favoured a contributory, earnings-related approach in the belief that such a system offered the best protection against escalating demands from recipients. But in 1937, the Canadian Supreme Court and the Judicial Committee of the British Privy Council (then the highest constitutional court for Canada) ruled that any ‘social insurance programs, which are financed in whole or in part by premiums paid by or on behalf of the potential beneficiary, fell within provincial jurisdiction’ (Reference BantingBanting, 1987, p. 49). This ruling left the Liberals powerless to enact the changes they wished to make to the pension system.

Even so, in the 1963 federal election campaign, the Liberals promised new legislation that would add an earnings-related tier to the existing system. That election produced a Liberal minority government after six years of Conservative rule and left the balance of power in the House of Commons in the hands of the social-democratic New Democratic Party. The prolonged process of federal–provincial bargaining that ensued allowed Ottawa to establish a contributory earnings-related pension tier. This required negotiation with the provinces because supplementary benefits (e.g. for widows, survivors, and the disabled) were not covered by the relevant 1951 amendment to the British North America Act (BNAA), then Canada's major constitutional document. Thus, federal entry into the realm of earnings-related pensions required provincial assent to another amendment to the BNAA (on the negotiations surrounding the creation of the Canada Pension Plan, see Reference BrydenBryden, 1974, chapter 8; Reference SimeonSimeon, 1972, chapter 3).

The dominant political dynamic in the creation of the CPP/QPP was one of asymmetrical turf-claiming, with a newly assertive Quebec government seeking to increase its policy autonomy and its ability to use pension contributions to develop the Quebec economy, a set of aspirations that was much less important to other provinces (Reference SimeonSimeon, 1972). To make the plan attractive to the provinces, Ottawa agreed to allow the provinces to borrow CPP surpluses as they accrued in the early years of the program. As mentioned above, and in contrast to the functioning of other social programs that are purely controlled by Ottawa or by the provinces (Reference Banting, Obinger, Leibfried and CastlesBanting, 2005), changes in the CPP must be approved by at least seven of the provinces representing two-thirds of the Canadian population. In practice, Quebec has a veto over major changes to the CPP because policymakers want to keep the Canadian and Quebec plans closely integrated (Reference Banting and IsmaelBanting, 1985). An opting-out clause in the constitutional amendment creating the CPP allowed any province to opt out and operate its own pension plan. In practice, only Quebec was interested in doing so, allowing Quebec to operate a distinct Quebec Pension Plan (QPP), retaining complete control over all investment funds in the QPP.

Because it was assumed that, beyond investment methods, both programs should be as similar as possible so as to not further complicate their administration or negatively impact the mobility of workers across provincial boundaries, contribution rates and eligibility and benefit levels in the CPP and QPP were harmonized, with a few exceptions. The provinces resisted benefit increases in the early years of the program because they did not want to have to pay back the funds they had borrowed. Moreover, as suggested above, changes in the structure of the CPP required the approval of a ‘super-majority’ of the Canadian provinces. Thus, the CPP/QPP has been a more difficult target for either expansionary or contractionary pension initiatives than pension programs within federal jurisdiction because the provinces have a collective ‘veto point’ (on veto points see Reference ImmergutImmergut, 1992). For these reasons, changes in CPP benefits have generally been at the margins.

Making CPP and QPP Fiscally Sustainable

As Béland (Reference Béland, Stoney and Doern2013) has noted, assertions that the decision process for CPP/QPP reform would result in the joint decision trap and policy stalemate enjoy mixed support. In the so-called ‘Great Pension Debate’ over expansion of the Canada Pension Plan in the 1970s and 1980s, policy change was blocked by opposition from Ontario (see Béland & Myles, Reference Béland, Myles, Bonoli and Shinkawa2005, pp. 257–258; Reference BantingBanting, 1987, chapter 5). But in the first half of the 1990s, projections that the CPP trust fund would be exhausted by the year 2015, leading to soaring contribution rates, put CPP reform back on the agenda. The most visible change in the CPP rescue package--and the one with the biggest fiscal impact–was in payroll taxes. Tax rates on employers and employees rose from 5.85% to 9.90%, shared equally between the two, over a six year period to finance a move away from Pay As You Go toward partial advance funding (see Table 2 for a summary of recent CPP and QPP changes).

This shift in financing was accompanied by the creation of the Canada Pension Board Investment Board (CPPIB), which is tasked with investing CPP surpluses to generate higher returns. Although this change reduced the gap between CPP and QPP because Quebec had long invested QPP surpluses, CPPIB is not grounded in economic nationalism, as promoting economic development at home is not part of its mission, in contrast to the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, which has invested QPP surpluses since the creation of the pension program (Béland, Reference Béland2006; Reference Weaver, Rein and SchmählWeaver, 2004a).

Decisions about what proposals on benefits to seriously consider in negotiations were clearly shaped by provincial veto points. In consultation documents, bureaucrats suggested a number of options for cutbacks, including an explicit 10% cut (from 25% to 22.5%) in replacement rates and increases in the normal and earliest retirement ages (Federal/Provincial/Territorial CPP Consultations Secretariat, 1996, p. 43). But in a 1996 discussion paper, the Quebec government rejected making most of the cuts to the QPP that would lead to the largest potential savings, including retirement age increases, cuts in the replacement rate, and cuts in indexation (Régie des rentes du Quebec, 1996). In theory, Ottawa could nevertheless have implemented major benefit cuts in the CPP if Quebec had either gone along with or was outvoted by the other provinces. But a strong desire on the part of all participants to keep the CPP and QPP closely integrated meant that the benefit cuts Quebec opposed were effectively off the table for both the CPP and QPP once Quebec had decided to oppose them. Thus the scope for change on the benefit side was dramatically reduced. An agreement was reached in 1997 on a package of CPP/QPP changes that dramatically increased payroll taxes, though not until after the next federal election, and made a number of cuts in CPP retirement benefits that were mostly technical in nature and difficult for beneficiaries to understand. In this case, overlapping provincial interests (notably, an interest in not having to pay back loans borrowed from the CPP at low interest rates) helped to overcome potential gridlock (Reference WeaverWeaver, 2004b).

The new CPP legislation also put a new ‘default’ or fail-safe procedure in place for ensuring the long-term financial viability of the CPP (for details, see Reference LittleLittle, 2008; see also Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2011). Quebec did not initially enact a similar fail-safe mechanism for the QPP, however. This situation would change barely a decade later as actuarial divergences between Quebec and the ROC forced Quebec policymakers to further reform the QPP in the name of fiscal sustainability. The less favourable actuarial situation of the QPP compared to the CPP is related to a host of economic and demographic factors. A number of these critical factors, for instance the fact that workers in Quebec retire earlier on average than those in the ROC, were summarized in the Quebec government's 2016 consultation document on QPP expansion (Retraite Quebec, 2016; for detailed perspectives on demographic aging and public policy in Quebec, see Reference MarierMarier, 2012). As a result of such complex factors, Quebec's ratio of persons of working ages (20–64) to those of age 65 and above, which was 3.5 in 2015, is expected to decline to 2 by 2030. This is comparable to the change anticipated in many western European countries, but is lower than that expected in the ROC (2.6) and the United States (2.7). Quebec also lags behind the ROC and the United States in the percentage of its older workers who are still in the labour force (Reference QuébecRetraite Quebec, 2016; p. 8, 11). This demographic and actuarial divergence means that contribution rates that are sufficient to keep the CPP solvent are no longer adequate for Quebec (for an early discussion, see Reference TamagnoTamagno, 2008).

The less favourable actuarial conditions in Quebec created strong pressures on provincial policymakers to enact changes to the QPP that are necessary to the long-term fiscal preservation of the program (on this issue, see Reference TamagnoTamagno, 2008). Cutting benefits would prove highly unpopular in Quebec due in part to the strong popular support for the CPP/QPP created by the flow of benefits from the program since the 1960s. In order to keep CPP and QPP benefits harmonized despite the less favourable actuarial conditions in the province, in 2011 the Quebec government instituted an ad hoc increase in QPP contribution rates of 0.9%, split equally between employers and employees, spread over a five-year period. This will be followed by the institution of an automatic stabilizing mechanism (ASM). Unlike the ASM for the CPP, the QPP's stabilizing mechanism will be entirely on the contribution rate side because benefit cuts would remove the symmetry between CPP and QPP benefits. The addition of a fail-safe to the QPP that is entirely on the contributions side suggests a very strong benchmarking effect for CPP/QPP benefits; it also suggests that policymakers in Quebec viewed benefit cuts, especially to levels below those in the CPP, as more politically sensitive than payroll tax rate increases.

CPP Expansion

An even more striking example of overcoming federal–provincial joint decision traps than the 1990s efforts to improve the fiscal sustainability of CPP/QPP has taken place in relation to proposals to expand earning-related public pensions. As in the United States, there have been strong concerns about pension inadequacy, especially given the decline of traditional defined-benefit pensions in the private sector. These concerns have been a key factor in legitimizing the push to expand CPP and QPP benefits. Although the 2008 financial crisis and its negative impact on personal savings and private pension funds increased the political pressure to expand these programs, this expansionary push is related to the long-term decline in coverage of Registered Pensions Plans (RRPs) offered by employers, especially defined-benefit plans. Drolet and Morissette (Reference Drolet and Morissette2014) sum up the situation across the country: ‘Between 1977 and 2011, the proportion of the overall employed population covered by RRPs declined from 52% to 37% among men, mainly because of a drop in defined benefit (DB) plan coverage. Among women, RRP coverage increased from 36% to 40% over the same period’ (p. 1). Despite this increase, when the two genders are combined, a significant decline in coverage is evident (Reference Drolet and MorissetteDrolet & Morissette, 2014). In 2011, RRP coverage for both genders in Quebec stood at 42.2%, slightly above the Canadian average (due in part to higher unionization rates in the province), but still nearly 5 points lower than in 1977 (Reference Cloutier-VilleneuveCloutier-Villeneuve, 2015, p. 2). The decline in RRP coverage, which primarily affect men (coverage for women actually increased between 1977 and 2011), and the overall shift from defined benefit to defined contribution pensions, are a source of policy drift (Reference HackerHacker, 2004) in the Canadian pension system, where private benefits have long played a central role due to the relatively modest replacement rates of public pensions (Reference Boychuk, Banting, Béland and GranBoychuk & Banting, 2008). Debated even before the 2008 financial crisis, this situation led a growing number of provinces to commission reports on the future of RRPs and, more generally, retirement security (e.g. Alberta/British Columbia Joint Expert Panel on Baldwin, Reference Baldwin2009; Pension Standards, 2008). This means that pension reform moved onto provincial policy agendas at the same time as it made its way onto the federal agenda.

Concerns about the impact of the 2008 financial crisis and policy drift affecting RPPs gave rise to a variety of policy proposals centred on the idea of expanding earning-related public pensions as a way to improve the economic security of future retirees. For instance, the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) campaigned to double the CPP replacement rate, from 25% to 50% of covered wages. The New Democratic Party (NDP) supported the push to expand CPP, as did a growing number of left-leaning experts who formulated various proposals that would raise the replacement rate of earnings-related pensions in one way or another (Béland, Reference Béland, Stoney and Doern2013).

In power as a minority government from 2006 and 2011 and, then, as a majority government until 2015, the Conservatives, led by Prime Minister Stephen Harper, were not ideologically-predisposed to support any expansion of the public pension system. In 2010, the minority Harper government briefly supported a modest CPP expansion. They later withdrew this support due in part to the small-business lobby's opposition to the increase in payroll contributions necessary to improve benefits (Béland, Reference Béland, Stoney and Doern2013). In the absence of action at the federal level during the Harper era, the Liberal Party of Ontario headed by Kathleen Wynne, in their 2014 provincial electoral platform, pledged to create the Ontario Retirement Pension Plan (ORPP) to extend supplemental pension benefit availability to those lacking ‘comparable’ workplace-based plans. After the election, Premier Wynne explicitly used the ORPP proposal to pressure the Harper government to expand CPP, a situation that led to a war of words between the Premier and the Prime Minister (Reference CsanadyCsanady, 2015). On the eve of the 2015 federal campaign, the role of Ontario was crucial in the pension debate, as it helped keep CPP reform on the agenda.

After a largely unanticipated electoral victory, the federal Liberal Party returned to power in November 2015. Strongly aligned ideologically with the Ontario Liberal government, during the election campaign, the Liberal Party of Justin Trudeau had pledged to expand the CPP, which would make the creation of ORPP unnecessary. In June 2016, the federal government and eight of the provinces (all but Quebec and Manitoba) reached an agreement to gradually increase the CPP replacement rate from 25% to 33.3%, while raising the combined payroll contribution rate from 9.9% to 11.9% between 2019 and 2023, and the maximum earnings limit from $54,900 to $82,700 between 2016 and 2025 (Department of Finance, 2016). Manitoba signed on to this agreement a few weeks later (Canadian Press, 2016).

In exchange for CPP expansion, Ontario would drop the ORPP proposal. Premier Wynne has argued that the impending implementation of Ontario's legislation provided an action-forcing mechanism that helped to facilitate a final agreement on a plan to expand the CPP instead of implementing the ORPP (Reference TaberTaber, 2016). On the CPP side, in short, the policy dynamic of CPP expansion is a complex one of federal supplantation even before Ontario's ORPP innovation went into effect. It reflected both the federal Liberals’ electoral commitments and threats from Ontario to race to the top. In addition to the key role of Ontario in the CPP expansion debate, the advent in May 2015 of an NDP government in the province of Alberta (which had been led by conservative governments since 1971) also facilitated reform, as Premier Rachel Notley supported reform, as did the federal NDP. In the end, all the nine provinces participating in CPP supported its expansion (Canadian Press, 2016). These remarks suggest that, since the 2015 election of the Trudeau Liberal government, the politics of CPP expansion have been driven by a combination of collusive bargaining between Ottawa and the provinces and race to the top pressures from Ontario's ORPP proposal.

The debate over QPP expansion

When the intergovernmental agreement on CPP expansion became public in June 2016, Quebec Finance Minister Carlos Leitão criticized the idea of doing the same thing with QPP because it would further increase workers and employers’ payroll contributions (Reference SalvetSalvet, 2017). This statement can be understood in the context of the province's less favourable actuarial projections and higher payroll contribution rates that are being phased in to just to keep benefits parallel with the current, pre-expansion CPP. Moreover, the Couillard Liberal government in power in Quebec City since April 2014 is more fiscally-conservative than the federal Trudeau government that supported CPP expansion. Indeed, the Couillard government faced massive criticisms from left-wing politicians and civil society actors for the austerity measures it adopted soon after taking office to balance the provincial budget (Reference PerreauxPerreaux, 2014).

Although QPP expansion might not otherwise have become a priority for the Couillard government, the expansion of CPP in the ROC created strong pressures on his government to do something about QPP, just as the ORPP proposal in Ontario put pressure on the federal government to expand CPP in the first place. In Quebec itself, support for QPP expansion came from a number of sources, including the province's powerful labour movement, a situation that further increased the pressure on the Couillard government to deal with the issue. In part for these reasons, in late 2016, the Quebec government unveiled a consultation document on QPP reform that outlined three policy alternatives: the status quo, an increase in benefits modelled on the CPP expansion announced earlier that year (with an increase of the replacement rate from 25% to 33.3%), and a more modest expansion the Couillard government had put forward during the negotiations leading to the June CPP agreement (Quebec, 2016). During the public consultations on QPP reform that followed the publication of this document, Quebec's labour unions boldly criticized the Couillard government's preferred proposal and strongly supported a QPP expansion modelled on the CPP expansion. As Serge Cadieux, the General Secretary of the Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Quebec (FTQ), told the Canadian Press, ‘Our plan must still be an equivalent to the CPP. We cannot accept that a retiree from Quebec would have less than a retiree from Alberta, New Brunswick, British Columbia, Nova Scotia or any other Canadian province’ (Canadian Press, 2016). The idea that pension benefits in Quebec should not be lower than the ones available in other provinces is consistent with Quebec nationalism, which legitimizes comprehensive social programs in the name of nation-building (Béland & Lecours, Reference Béland and Lecours2006; Canadian Press, 2016). Moreover, because of interprovincial labour mobility and the fact that many companies in Canada employ workers both in and outside Quebec, having different benefit structures and replacement rates for old-age pensions in CPP and QPP would be ‘very, very complicated’ (Leitão quoted in Montgomery, Reference Montgomery2017).

In May 2017, after the end of the public consultations on QPP reform, it was reported that the Couillard government decided to abandon its less generous plan to support an increase in the program's replacement rate from 25% to 33.3%, modelled after the CPP expansion announced 11 months earlier (Reference SalvetSalvet, 2017). Despite the initial objections of Finance Minister Leitão, under pressure from key stakeholders and facing the race to the top effect created by CPP expansion, the Couillard government reluctantly adopted the approach it had initially criticized that would push payroll contribution rates above those of the CPP, once again due to Quebec's less favourable actuarial situation. The fact that Quebec's next provincial election is set for 2018 creates further incentives for the Couillard government to announce an increase in QPP benefits that could improve its public image, which was negatively affected by the politics of austerity it embraced during its first two years in office. In early November 2017, the Couillard government finally tabled legislation in the province's National Assembly to expand QPP benefits along the lines of the previously-announced CPP benefit increase (Reference MontgomeryMontgomery, 2017).

Discussion

As the above discussion makes clear, the dynamics of CPP and QPP policy change over the past two decades have been complex rather than simple, and have evolved over time, reflecting both changing (and increasingly disparate) actuarial projections and fluctuating political pressures. First, over the years, due to Quebec's less favourable actuarial projections compared to the ROC, the QPP has faced stronger actuarial challenges than the CPP. The Quebec government has addressed this challenge through a gradual increase in payroll contributions adopted in 2011. This reality points to the fact that, although public policies can become more resilient over time, they can also generate self-undermining patterns, for instance in the context of less favourable economic and demographic circumstances (on this issue see Béland, Reference Béland2010; Reference Jacobs and WeaverJacobs & Weaver, 2015; Reference WeaverWeaver, 2010). The contrast between CPP and QPP and Quebec's decision to increase payroll contribution above those of CPP to address looming actuarial shortfalls illustrates how these self-undermining processes can create growing policy asymmetries within a fragmented federal system.

Second, multiple policy dynamics of federalism shaped the politics of CPP and QPP reform in direct ways. Collusive bargaining between Ottawa and the provinces dominated the politics of restructuring in the mid-1990s. The politics of CPP expansion in the mid-2010s, culminating in the expansion of CPP after the election of the Trudeau Liberal government in November 2015 reflected a combination of collusive bargaining with a muted form of an electorally-driven race to the top (perhaps better labelled an ‘upward jog’) in which Ontario's ORPP proposal played a critical role. In Quebec, CPP expansion combined with electoral and political factors internal to Quebec, such as labour mobilization, sub-state nationalism, and the electoral calendar, shaped the politics of QPP expansion, creating the same sort of muted race to the top (in this case, ‘race to match the Rest of Canada’), making it harder for the Couillard government to either adopt a more modest expansion of QPP benefits or forego a benefit increase altogether.

This study suggests the variety of potential patterns of federal policy dynamics and the manners in which these patterns can change over time. It also suggests these patterns interact with changing economic and demographic factors to impact the deliberations and mobilizations of individual and collective actors involved in policy reform. More research about such diverse and influential interactions is needed to move forward the comparative analysis of social policy stability and change in federal countries.

Acknowledgement

A previous version of this paper was presented in March 2018 at the Toronto Public Policy and Governance Workshop (University of Toronto). The authors thank the participants, as well as Rachel Hatcher, Patrik Marier, Alex Waddan, and the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions. Daniel Béland acknowledges support from the Canada Research Chairs Program.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.