Introduction

Does globalisation influence social expenditure? The literature predicts that globalisation can either lead to a retrenchment or an expansion of the welfare state (Koster, Reference Koster2009; Ursprung, Reference Ursprung, Durlauf and Blume2008), but only recently has it tried to isolate the effect of the various manifestations of globalisation (Potrafke, Reference Potrafke2019; Yay & Aksoy, Reference Yay and Aksoy2018). Globalisation has often been blamed for the decrease in social expenditure, at least in the public discourse and among the general public, and in particular economic globalisation. But political factors such as the participation in international treaties and organisations that influence domestic choices regarding the welfare state may also have played a role, and so political globalisation should act independently of economic globalisation. Social globalisation may also increase the perceptions of the benefits and costs of foreign welfare regimes and thus its effect on social expenditure may be different from that of economic and political globalisation. Additionally, the same impact of globalisation on total social expenditure can translate into different compositions of the welfare system. This is particularly important in the aftermath of the 2007–2008 financial and economic crisis and the Great Recession that ensued, bringing the welfare state to the forefront of the debate on the need to limit public spending given the historically high public debt ratios in many countries (Kiess et al., Reference Kiess, Norman, Temple and Uba2017; Vis, van Kersbergen, & Hylands, Reference Vis, van Kersbergen and Hylands2011).

The initial research question is separated in two: Which dimensions of globalisation have an impact on social expenditure? How do different components of social expenditure react to globalisation? This study investigates these relationships for 36 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries over the period 1990–2015 estimating an empirical model with system Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) to more adequately address endogeneity (Potrafke, Reference Potrafke2015) since it is important, from a policy perspective, to determine whether there is a causal effect running from globalisation to social expenditure. This approach allow us to analyse the links between different dimensions of globalisation, defined based on the Swiss Economic Institute (KOF) index of globalisation, and different social spending programmes, classified into nine spending types according to the OECD Social Expenditures Database (SOCX) (OECD, 2019), plus education, taking also into account a set of control variables expected to play a relevant role in explaining the dynamics of welfare efforts.

Understanding how different dimensions of globalisation influence welfare effort contributes to a better understanding of the welfare trajectories observed in different countries and can help to predict what will happen to the respective welfare states in the near future. This will be particularly important in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemics, which some argue is “killing globalisation” and especially economic globalisation, with its global supply chains, resulting in travel bans and reduced international trade and investment flows that might have a permanent effect on different aspects of globalisation (Baldwin & Tomiura, Reference Baldwin, Tomiura, Baldwin and Mauro2020; Sforza & Steininger, Reference Sforza and Steininger2020). Another contribution of this study pertains to a detailed analysis of the impact of globalisation on the composition of social policy by disentangling the relationship with different social spending programmes using an encompassing classification. Our focus is neither exclusively on total public social expenditure, nor on certain components of social expenditure taken in isolation. By disentangling the impact of globalisation on different social spending programmes, we facilitate the comprehension of the mechanisms of transmission from globalisation to different social and economic outcomes. Indeed, the increase in globalisation since the 1980s has raised a lot of interest in the social and economic outcomes of these dynamics as patent in e.g. Tsai (Reference Tsai2007), Copestake (Reference Copestake2015) and Heimberger (Reference Heimberger2020). Our disaggregated analysis contributes to a better understanding of how globalisation impacts poverty, inequality, long run growth and economic recovery, relationships that have been under close scrutiny (Gurgul & Lach, Reference Gurgul and Lach2014; Potrafke, Reference Potrafke2015; Wade, Reference Wade2004), through the design of social policy (Cammeraat, Reference Cammeraat2020; Crociata et al., Reference Crociata, Agovino, Furia, Osmi, Mattoscio and Cerciello2020). At the same time, we provide a more comprehensive picture of the role played by different dimensions of globalisation, helping to distinguish the effect of economic globalisation from that of other dimensions. From a methodological point of view, we contribute to the literature by addressing endogeneity issues using an instrumental variable for globalisation based on the level of globalisation of neighbouring countries and applying the system GMM estimation procedure.

The paper proceeds as follows: the next section provides an overview of the literature on the relationship between globalisation and the welfare state with a focus on different dimensions of globalisation and social spending programmes. The “Methodology and data” section presents the methodology and data used in the empirical analysis, the results of which are presented and discussed in the “Results” section. The main conclusions are summarized in the “Conclusion” section.

Literature overview

Dimensions of globalisation and the size of the welfare state

Previous literature has sought to explain and provide evidence on the links between globalisation and the welfare state. Schulze and Ursprung (Reference Schulze and Ursprung1999) provide an extensive review of the theoretical arguments and earlier empirical evidence. This literature suggests contrasting effects of globalisation on the welfare state putting forward different explanations for why globalisation should affect social expenditure: a positive effect since globalisation leads economic agents to demand for more state intervention that promotes welfare for all as the benefits of globalisation are not equally shared (compensation theory); and a negative effect due to the need to promote international competitiveness through reduced taxation, which in turn reduces the ability to finance the welfare state (efficiency theory). Another strand of the literature relates the development of the welfare state with other features, such as population ageing, ideology of the political parties in power, the historical and cultural nature of welfare intervention or deindustrialisation, rendering globalisation insignificant as a determinant of social expenditure (Brady, Beckfield, & Seeleib-Kaiser, Reference Brady, Beckfield and Seeleib-Kaiser2005).

But globalisation is a multi-dimensional phenomenon and certain aspects of globalisation (economic, political, social) may be more important than others with regard to welfare policies. Economic globalisation through trade, foreign direct investment and financial liberalisation involves more risks and uncertainty at the economic level resulting in a higher demand for social policies, but it also exposes countries to international competition and can thus result in less tax revenues that translate into lower public expenditure, including in welfare programmes. Political and social globalisation imply that more governments and people are connected and acknowledge welfare practises in other countries. Simmons, Dobbin, and Garrett (Reference Simmons, Dobbin and Garrett2006) argue that political globalisation is responsible for the spread of neo-liberalism, which might constitute a threat to the welfare state. Huber and Stephens (Reference Huber and Stephens2003) pose that a greater influence of the International Monetary Fund can result in lower public expenditure, an imposition accepted in the context of bailout agreements. On the other hand, social globalisation means that citizens from different countries are aware of social protection levels provided by other nations and so social expenditure could be driven by aspirations to more advanced welfare models.

The former discussion suggests that the issue is essentially empirical but the considerable applied literature spurred by the foregoing theoretical arguments has reached no consensus. This is illustrated by a few recent studies. In a meta-regression analysis of 79 articles corresponding to 1,182 estimated coefficients of the effect of economic globalisation on government spending, Heimberger (Reference Heimberger2020) concludes that there is no evidence of a non-zero average effect but when looking at specific components of government spending, economic globalisation has a small-to-moderate negative impact on social spending. Haelg, Sturm, and Potrafke (Reference Haelg, Sturm and Potrafke2020) identify a set of robust determinants of social spending in 31 OECD countries over the period 1980–2016 using extreme bounds analysis and Bayesian model averaging to deal with model uncertainty. They find evidence of an association between social expenditure and trade and social globalisation, negative in the former and positive in the latter. Focusing on total social spending (as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product – GDP) and the KOF index of globalisation, Schuknecht and Zemanek (Reference Schuknecht and Zemanek2020) cannot find evidence of a statistically significant influence of globalisation on social expenditure for a sample of 21 advanced economies from 1980 to 2016. Potrafke (Reference Potrafke2019) investigates 21 Asian non-OECD countries over the period 2000–2014 and concludes that none of the three dimensions of the KOF globalisation index has an influence on the dynamics of social expenditure. Yay and Aksoy (Reference Yay and Aksoy2018) also disaggregate the KOF globalisation index in its economic, social and political dimensions to assess the impact of globalisation on social security transfers in a sample of 23 developed countries plus 9 transition economies from 1980 to 2010. For the whole sample the results do not support the influence of any dimension of globalisation. For a wider sample of 186 countries for the 1970–2004 period, Meinhard and Potrafke (Reference Meinhard and Potrafke2012) conclude that economic globalisation has no effect on the government consumption share of GDP (the measure of welfare state effort), while social and political globalisation revealed a positive association, more intense in the first case.

Globalisation and social welfare policies

The welfare state encompasses a large number of programmes, reflected in different types of social expenditure. The same overall impact of globalisation can translate into different compositions of the welfare system, which can have important implications for social inclusion and economic performance. Kim and Kim (Reference Kim and Kim2017) investigate the efficiency of the nine different social spending programmes identified by the OECD in terms of combating inequality using the stochastic frontier model. The results for 22 OECD countries over the period 2004–2012 indicate that unemployment and family benefits are the only programmes that reduce inequality. As far as economic performance is concerned, increasing certain components of social spending can influence capital accumulation and productivity, essential to sustain growth in modern knowledge-based economies and ensure equality of opportunities (Garritzmann, Busemeyer, & Neimanns, Reference Garritzmann, Busemeyer and Neimanns2018). Additionally, in the short run, social expenditure programmes present spending multipliers with different intensities and thus play different roles in economic recovery (Furceri & Zdzienicka, Reference Furceri and Zdzienicka2012). Crociata et al. (Reference Crociata, Agovino, Furia, Osmi, Mattoscio and Cerciello2020) assess the differentiated economic impact of old age, disability, sickness, social exclusion, family-children and unemployment benefits using Panel Vector Autoregression models for a sample of 15 European Union (EU) countries over the period 1995–2013. Their findings indicate that the relationship with GDP is negative for old age and unemployment benefits but positive for disability, sickness/health, social exclusion and family spending. Cammeraat (Reference Cammeraat2020) investigates the impact of six social expenditure schemes on poverty, inequality and GDP growth in a sample of 22 EU countries over the period 1990–2015, concluding that the sign of the relationships varies substantially between the different social schemes. Thus, globalisation, by impacting differently the various social spending programmes, can lead to quite varied social and economic outcomes. On a different note, Schuknecht and Zemanek (Reference Schuknecht and Zemanek2020) analyse the risk of what they dub as “social dominance,” “(…) a situation in which social expenditures dominate fiscal policy and undermine economic growth and fiscal sustainability.” (p. 1). Using data for 21 advanced economies over the period 1980–2016, they conclude that the increase in social expenditure as a percentage of GDP was financed to an important extent by a decline in other primary expenditures (crowding out). A disaggregated analysis assuming that public spending in infrastructures, education and core public administration is more productive than social spending suggests that crowding out applies mainly to expenditure on infrastructures and thus may negatively affect growth.

If social spending is mainly directed to old age, a likely scenario in the current context of rapid population ageing, then it will probably react very little to globalisation since it will be mostly determined by demographics. Another example of the lack of association between economic globalisation and social spending applied to unemployment benefits is provided by Huber and Stephens (Reference Huber and Stephens2003): if an important part of employment is in the public sector, less affected by economic shocks, we should not expect to see a strong relationship with globalisation. Health and education expenditures, on the other hand, are expected to show a positive association with globalisation, in its different dimensions, both because they are seen as a means to improve social mobility and because they result in human capital accumulation that lessens the risks of unemployment associated with stronger competition and makes countries more competitive in international markets. Also, if globalisation occurs mainly through foreign direct investment it is probably in the best interest of multinational corporations to have available a healthy and educated workforce.

At the empirical level, Dreher, Sturm, and Ursprung (Reference Dreher, Sturm and Ursprung2008) investigated the influence of globalisation on the composition of government expenditures for a sample of 15 OECD countries over the period 1990–2001 but found no impact (overall and different dimensions). Kim and Zurlo (Reference Kim and Zurlo2009) analyse the relationship between economic globalisation and active and passive labour market spending and social service spending. The sample is composed of 18 affluent economies over the period 1980–2001 and the findings reveal a negative relationship for active and passive labour market spending and a positive one for social service spending. Taking a different approach in terms of dependent variable, Leibrecht and Fiong (Reference Leibrecht and Fiong2017) conduct duration analyses on a cross-section of nearly 100 economies among which 28 privatised their pension system between 1981 and 2012. They conclude that high growth in economic and political globalisation is conducive to pension privatisation and so more likely to result in a reduction of old age social expenditure.

Methodology and data

We investigate how social expenditure is affected by various manifestations of globalisation based on a parsimonious empirical model that includes other potential social expenditure determinants considered in previous studies (Haelg, Sturm, & Potrafke, Reference Haelg, Sturm and Potrafke2020; Kim & Zurlo, Reference Kim and Zurlo2009; Leibrecht, Klien, & Onaran, Reference Leibrecht, Klien and Onaran2011; Meinhard & Potrafke, Reference Meinhard and Potrafke2012; Potrafke, Reference Potrafke2019; Schuknecht & Zemanek, Reference Schuknecht and Zemanek2020; Yay & Aksoy, Reference Yay and Aksoy2018). The baseline regression is given by:

where SocExp is the social expenditure indicator in country i at time t; Glob is the globalisation indicator; X denotes the vector of control variables and ϑ t , ϑ 𝑖 and ε 𝑖, represent the time fixed-effects, the country fixed-effects and the error term, respectively. The dataset includes the current 36 OECD countries over the period 1990–2015.

We consider different public social expenditure indicators, SocExp, drawing from OECD SOCX that provides disaggregated comparable data on social expenditure detailed in nine policy areas (see Table 1) taken as a percentage of GDP. Additionally, we use World Development Indicators (WDI) from the World Bank to retrieve data on public education expenditure. The choice of social expenditure as dependent variable in assessing welfare state change has been criticised (Siegel, Reference Siegel, Clasen and Siegel2007), namely because some components act as automatic stabilizers thus responding not to exogenous changes that influence the development of the welfare state, eg. globalisation, but to the business cycle (Darby & Melitz, Reference Darby and Melitz2014), raising in recessions and becoming lower in expansions (counter-cyclical). We control for the influence of the business cycle on social expenditure in two ways: through the introduction of time effects, that account for common specific episodes related to the business cycle, and by considering the unemployment rate as an explanatory variable. Additionally, the concern of this study is with how globalisation influences social policy design, i.e. examine whether governments increased or constrained spending across the spectrum of welfare programmes in response to globalisation since the main instrument of implementation of public policies is spending (Siegel, Reference Siegel, Clasen and Siegel2007). Its use is also justified for comparison purposes as studies that analyse the importance of the welfare state for economic and social outcomes also usually rely on this measure. Ideally, for assessing the development of the welfare state one should use a wider range of measures but this is hindered by limited and comparable data availability (for a recent study that deals with this issue see Otto & van Oorschot, Reference Otto and van Oorschot2019).

Table 1. Variables and sources.

Abbreviations: GDP, Gross Domestic Product; OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; WDI, World Development Indicators.

Glob represents globalisation and its different dimensions. As proxies we use the KOF indices of globalisation (overall, economic, political, social) provided by the Swiss Economic Institute (KOF), Gygli et al. (Reference Gygli, Haelg, Potrafke and Sturm2019). The KOF sub-indices measure different manifestations of globalisation: (1) economic: incorporates trade, foreign direct investment and portfolio investment flows but also economic restrictions on international trade, investment and capital movements; (2) political: uses information on, among others, the number of embassies in a country, the number of international organizations to which a country belongs and the number of international treaties signed and (3) social: considers the interaction between citizens of different countries through personal contacts, including data on international telephone traffic, information flows, the global dissemination of ideas and cultural proximity. The KOF overall globalisation indicator aggregates the former three subcomponents. An additional new feature of the most recent update of the KOF globalisation index is the distinction between de jure and de facto globalisation (Gygli et al., Reference Gygli, Haelg, Potrafke and Sturm2019; Haelg, Sturm, & Potrafke, Reference Haelg, Sturm and Potrafke2020). The former measures policies and conditions that should enable, facilitate and foster flows and activities, while the latter accounts for actual international flows and activities. Since in principle de jure globalisation is a prerequisite for de facto globalisation and it is difficult to arrive at appropriate theoretical justifications about whether de facto globalisation influences social spending to a larger extent than de jure globalisation (or vice versa) we do not distinguish between the two. Additionally, to obtain our balanced dataset we imputed missing values applying the method proposed by Honaker, King, and Blackwell (Reference Honaker, King and Blackwell2011). Since this method uses the information on all the other relevant variables in the databases a multicollinearity problem would arise if we considered both measures.

The vector X includes a set of controls selected based on previous studies. We control for country size (log population, lpop), macroeconomic stability/business cycle (unemployment rate, unemprate), the government effectiveness (gee) and government size (total government expenditure, govexp). lpop controls for country size and a positive relationship is expected according to Wagner’s law that predicts that as a country gets richer and population bigger public spending increases (Jibir & Aluthge, Reference Jibir and Aluthge2019). unemprate, corresponding to unemployment as a percentage of the labour force is expected to influence social spending positively since more unemployment implies more demand for social benefits. gee captures the joint perception of the quality of public services, civil services, policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the commitment to such policies by governments. It is included to control for the effectiveness and efficiency of government’s social policies. However, its effect is still a source of discussion. According to Mizrahi (Reference Mizrahi2016), higher government effectiveness leads to lower social expenditure since voters believe that a well-managed government protects equally the standards of living of the whole population, including the economically weak, and thus prefer less government intervention. On the other hand, Rothstein, Samanni, and Teorell (Reference Rothstein, Samanni and Teorell2012) and Svallfors (Reference Svallfors2013) suggest that there may exist a positive relationship because society is more inclined to support welfare policies if there is a sense of fairness and efficiency of public institutions. govexp intends to capture the importance of the public sector in an economy. A positive relationship with the share of social expenditures is expected since in more interventionist states expenditures in social protection are probably of more importance. An important strand of the literature on the size of the welfare state links it also with ideology of the political parties in power, so we also tried including in vector X an indicator of government’s ideology. We followed Haelg, Sturm, and Potrafke (Reference Haelg, Sturm and Potrafke2020) and included a dummy variable for left-wing governments computed using the data by Cruz, Keefer, and Scartascini (Reference Cruz, Keefer and Scartascini2018), expecting a positive influence since leftist governments are assumed to increase social expenditures relative to chief executives from the centre and right political spectrum, as suggested by Kittel and Obinger (Reference Kittel and Obinger2003) and Potrafke (Reference Potrafke2009). However, the estimated coefficient for government’s ideology although usually positive was never statistically significant. Since this variable neither enters our specifications with a statistically significant effect nor does its inclusion change substantively the main result highlighted by this study, we decided not to include these results. The empirical literature addressing the partisan explanation of welfare state development also presents more recent evidence supporting the decline of the influence of partisan differences with regard to social expenditures (Kittel & Obinger, Reference Kittel and Obinger2003; Negri, Reference Negri2021). Bandau and Ahrens (Reference Bandau and Ahrens2020) review 63 empirical studies on the topic and conclude that the most important factor affecting the results is the choice of the dependent variable, with studies using entitlements four times more likely to find partisan effects than studies based on social spending. The dichotomous left–right classification of political parties has also been criticised (Negri, Reference Negri2021). Contributing to these debates is beyond the scope of this study.

We work with a balanced panel data to improve statistical power and inference, which implied imputing missing observations applying a statistical approach known as the multiple imputation method from Honaker, King, and Blackwell (Reference Honaker, King and Blackwell2011) – Amelia II, which assumes a missingness matrix where every single variable included is linearly estimated using the information from all the other variables. This approach uses the expectation–maximization with bootstrap (EMB) algorithm that combines the classic expectation–maximization (EM) algorithm, suggested by Dempster, Laird, and Rubin (Reference Dempster, Laird and Rubin1977) with bootstrap resulting from an EMB approach. See also Honaker and King (Reference Honaker and King2010). Details on the variables used and respective sources are reported in Table 1. Summary statistics for the variables used with the corresponding percentage of missing values are presented in Table 2 suggesting there is sufficient variation in the data to allow us to identify the effect of globalisation on social expenditure.

Table 2. Summary statistics.

The correlation matrix for the variables of interest, social expenditures and globalisation, is provided in Table 3. The correlation coefficients are positive (the exception is the correlation coefficient between education expenditure and political globalisation, −0.0204) suggesting that globalisation did not pose a threat to the welfare state. The association is stronger for some components of social spending, health related benefits, active labour market policies, old age, incapacity and family benefits. The quantitative importance of the correlation with different dimensions of globalisation thus seems to vary across social programmes. This evidence is only indicative since correlation is not causation and to arrive at robust conclusions, we need to take into account other determinants of social spending using multivariate regression analysis.

Table 3. Correlation matrix between globalisation and social expenditures.

The estimation of equation (1) using panel data models such as fixed effects or random effects models gives an indication of the conditional correlations between globalisation and social expenditure, but since those methods do not deal with endogeneity, they only provide descriptive evidence on this link (Dorn, Fuest, & Potrafke, Reference Dorn, Fuest and Potrafke2018). From a policy perspective it is important to determine whether there is a causal effect running from globalisation to social expenditure. Two reasons for endogeneity of the globalisation variable in our model are omitted variable bias and reverse causality. Although common panel data models allow us to address omitted variable bias, eg. in fixed effects models by controlling for time-invariant unobservable drivers of social expenditure, they do not control for reverse causality, highly likely (Potrafke, Reference Potrafke2015). For instance, social spending can increase competitiveness by increasing the availability and quality of human capital through health and education expenditures and lead countries to become more globalised at the economic level. It is also possible that more globalised countries are also those that experience higher levels of competitiveness, which in turn allows them to generate more aggregate income and in this way finance higher levels of social spending (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Görg, Görlich, Molana, Montagna and Temouri2014; Grauwe & Polan, Reference Grauwe and Polan2005). Görg, Molana, and Montagna (Reference Görg, Molana and Montagna2009) find that in OECD countries inward Foreign Direct Investment flows are positively affected by social expenditure. To truly identify the influence of globalisation on social expenditure we need to use an instrumental variable approach, in this way guaranteeing consistent parameter estimation in equation (1), ie. that the error term is uncorrelated with the covariates. Furthermore, there may be also problems associated with countries heterogeneity, measurement error and persistence of the dependent variable.

A suitable estimator under these circumstances is GMM since it allows to correct for reverse causality through the use of instrumental variables and also controls for omitted variable bias by removing fixed effects through differencing. The criterion for the proper application of GMM is met since the number of time observations for each cross-section (26) is lower than the number of countries (36). The first version of GMM uses differencing as its main property (Diff-GMM), Arellano and Bond (Reference Arellano and Bond1991). Arellano and Bover (Reference Arellano and Bover1995) extended the estimator to include also the regression in levels (System-GMM) showing that it leads to more robust results, mainly because the instruments used in Diff-GMM (lagged levels of the variables) are weak when the series are persistent, Bond, Hoeffle, and Temple (Reference Bond, Hoeffle and Temple2001). Since we suspect persistency in social spending (Anderson & Obeng, Reference Anderson and Obeng2020) the use of the System-GMM is an appropriate solution, providing less biased and more precise results by combining the moment conditions for the model in first differences and for the model in levels. We applied System-GMM following the rules of thumb suggested by Roodman (Reference Roodman2009): (1) we include time dummies to ensure that estimations are not correlated across individuals; (2) only globalisation measures are assumed endogenous and the remaining variables are considered strictly exogenous and (3) System-GMM is performed in first differences deviations from a two-step estimate with Windmeijer correction, Windmeijer (Reference Windmeijer2005).

The adequate solution for reverse causality is the use of proper instruments. Recent studies instrument a country’s own globalisation with the globalisation levels of neighbouring countries, eg. Lang and Tavares (Reference Lang and Tavares2018) and Pleninger and Sturm (Reference Pleninger and Sturm2020). We use the former approach to define our instrument for globalisation, proximity globalisation (PG). PG for country i at time t is computed as the weighed sum of the lagged level of globalisation (Globj,t-1

) of the remaining countries in the sample, j (j ≠ i). The weights

![]() $ (\frac{1}{{\mathrm{distance}}_{i,j}}) $

correspond to the inverse of the population-weighted geographical distance between countries i and j from Mayer and Zignago (Reference Mayer and Zignago2011). The population-weighted geographical distance specifically measures the bilateral distance (using latitudes and longitudes) between two countries weighted by the population share of main agglomerations within those countries. PG is thus given by:

$ (\frac{1}{{\mathrm{distance}}_{i,j}}) $

correspond to the inverse of the population-weighted geographical distance between countries i and j from Mayer and Zignago (Reference Mayer and Zignago2011). The population-weighted geographical distance specifically measures the bilateral distance (using latitudes and longitudes) between two countries weighted by the population share of main agglomerations within those countries. PG is thus given by:

$$ {\mathrm{PG}}_{i,t}=\frac{\sum_{j\ne i}(\frac{1}{{\mathrm{distance}}_{i,j}}\times {Glob}_{\hskip-.05em j,t-1})}{\sum_{j\ne i}\frac{1}{{\mathrm{distance}}_{i,j}}}. $$

$$ {\mathrm{PG}}_{i,t}=\frac{\sum_{j\ne i}(\frac{1}{{\mathrm{distance}}_{i,j}}\times {Glob}_{\hskip-.05em j,t-1})}{\sum_{j\ne i}\frac{1}{{\mathrm{distance}}_{i,j}}}. $$

PG measures the globalisation environment surrounding each country, overall and for the different components of globalisation and is thus higher if the external environment of globalisation is strong, especially in countries in close geographical proximity. This is based on the idea of peer effects in a country’s own globalisation level, expected to be closely related albeit with a lag, with successful opening up in neighbouring countries, due to competition, coercion or imitation, ie. globalisation in its different dimensions diffuses from neighbouring countries to the home country (Anderson & Obeng, Reference Anderson and Obeng2020; Berggren & Nilsson, Reference Berggren and Nilsson2015; de Soysa & Vadlamannati, Reference de Soysa and Vadlamannati2011; Yay & Aksoy, Reference Yay and Aksoy2018). The validity of our instrument also demands that it satisfies the exclusion restriction – our instrument should not vary systematically with the error term in our empirical model. In other words, it should not have an independent effect on social expenditure other than through the instrumented variable, the country’s own level of globalisation. As suggested by de Soysa & Vadlamannati, Reference de Soysa and Vadlamannati2011, we know of no empirical or theoretical argument linking geographic distance (exogenous) and average globalisation levels of a region with social policy decisions of an individual government. To give an example, the level of globalisation in the OECD as a whole and the geographic distance of Portugal to other OECD countries should not influence Portugal’s own social expenditures behaviour except if they lead to changes in Portugal’s own globalisation levels, which in turn pressures the Portuguese government to change social expenditure, the hypothesis we want to test. Arguably valid instruments are hard to come by since it is difficult to rule out all alternative channels that would violate the exclusion restriction with absolute certainty, as pointed out by Lang and Tavares (Reference Lang and Tavares2018). The validity of the instruments used in our estimations was checked using the Hansen test for overidentifying restrictions (Hansen, Reference Hansen1982), which amounts to a test for the exogeneity of the covariates (see Tables 4 and 5). The null hypothesis was never rejected at conventional levels of significance thus confirming that PG does not influence social expenditure directly or through other explanatory variables not included in our model.

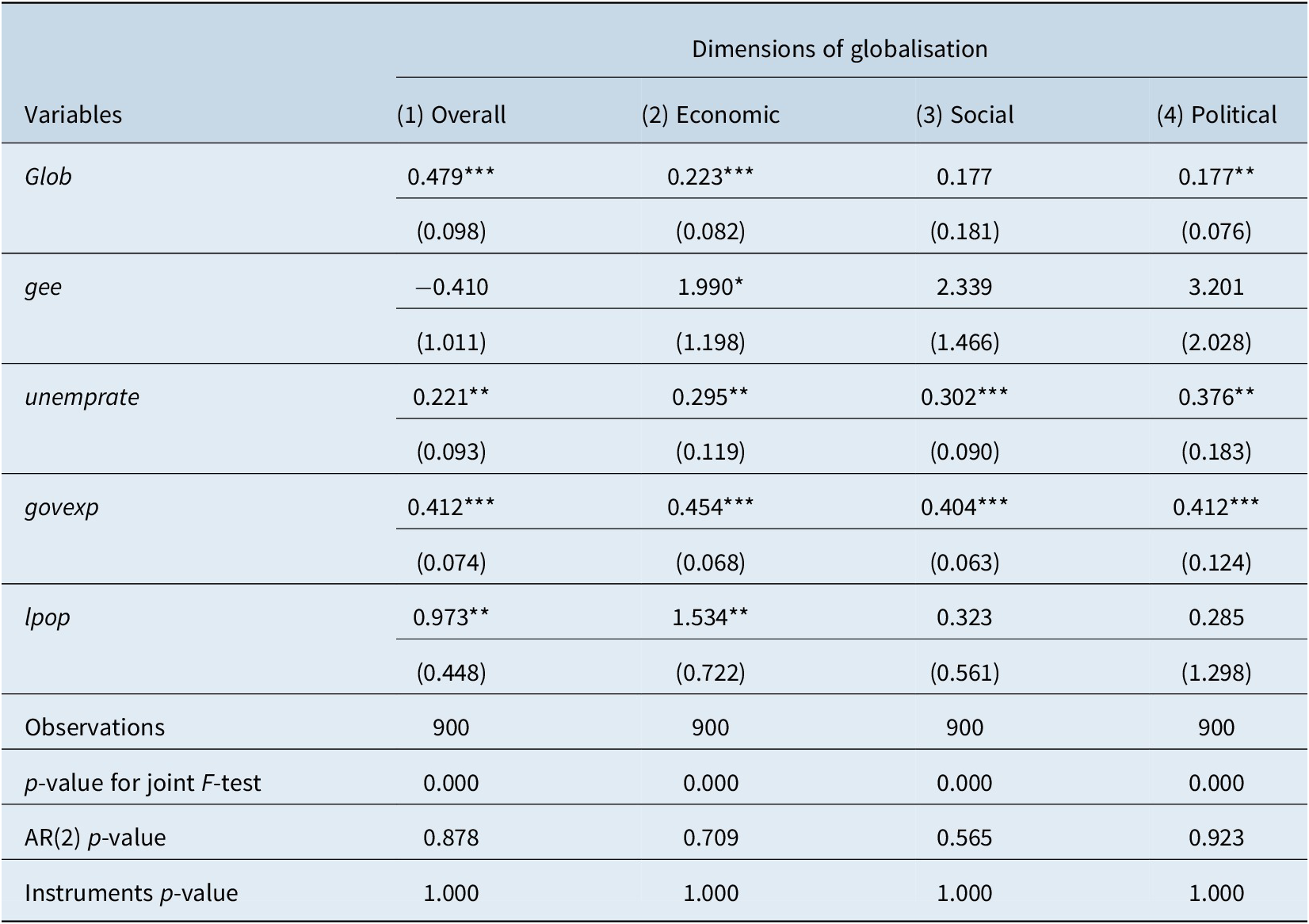

Table 4. System-generalised method of moments (GMM) results: Total public social expenditure and dimensions of globalisation.

Notes: regressions include time dummies; standard errors in parenthesis. ***, ** and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. The models were estimated assuming globalisation as endogenous and corrected by two types of instruments: lagged globalisation and proximity globalisation (PG); System-GMM was performed in first differences deviations, two-step estimation and with Windmeijer-corrected cluster–robust errors. “AR(2) p-value” is the Arellano-Bond test for second order serial correlation under the null of no serial correlation; “Instruments p-value” is the p-value for Hansen test of overidentification under the null of joint validity of instruments.

Table 5. Summary of system-generalised method of moments (GMM) results: Social spending programmes and dimensions of globalisation.

Notes: See notes to Table 4.

Results

We begin by assessing the impact of globalisation, overall and according to the three dimensions of the KOF globalisation index, on total public social expenditure as a percentage of GDP. According to the results presented in Table 4, the overall globalisation index is statistically significant in explaining the evolution of total social spending with a positive sign and the effects exerted by each sub-index individually, economic, social and political, confirm those for the overall index. However, the influence of social globalisation is not statistically significant. These results indicate that if overall globalisation increases by one point, the total public social expenditure ratio will rise by about 0.5 percentage points, a sizeable effect of globalisation on social policy. This disaggregates into a 0.22 percentage points increase stemming from a one point increase in economic globalisation and a 0.18 percentage points increase resulting from a one point increase in political globalisation, while the 0.18 percentage points increase from the change in social globalisation is not statistically significant. The former results thus support the compensation hypothesis according to which as globalisation proceeds citizens demand higher levels of social protection in order to be compensated for the risks associated with globalisation. These findings suggest that social expenditure in the average OECD country is mainly determined by economic globalisation, probably because the associated increased uncertainty and economic risks lead voters to demand for more social protection, and also by political globalisation since the trend has been for governments to participate in an increasing number of regional agreements and supranational organisations that imply common goals.

Regarding the control variables, the signs and statistical significance of the respective coefficients are robust to the choice of the measure of globalisation. All the estimated coefficients of the control variables are statistically significant at least at a 5% level (except gee in columns 1, 3 and 4 and lpop in columsn 3 and 4). In the regression with overall globalisation, the estimated coefficient for government effectiveness presents a negative sign, in line with Mizrahi (Reference Mizrahi2016), but is not statistically significant. With the dimensions of globalisation measures, the results suggest on the contrary a positive relationship, which is only statistically significant when using economic globalisation. The unemployment rate presents the expected positive sign. Higher total public expenditure as a percentage of GDP is an indication of a more interventionist state and so we get the expected positive coefficient. Bigger countries, with a larger population, are also more likely to present a bigger share of social expenditure, which is confirmed by the positive coefficient for lpop although only statistically significant in the regressions with social and political globalisation. The p-values for the autocorrelation (AR2) and Hansen tests results indicate that it is not possible to reject the null hypothesis of, respectively, no serial correlation and the joint validity of the instruments used.

We next investigated whether the positive impact of globalisation on total social public expenditure also applies to different social welfare policies. We considered as dependent variable each of the nine categories of social expenditure included in the OECD SOCX database and also public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP from the WDI. Table 5 contains a summary of the results focusing on the globalisation variables suggesting that the impact of globalisation varies according to different types of welfare policy. Overall globalisation expands all types of social expenditure (except education) but it is only statistically significant in the case of old age pensions, incapacity, family, active labour market policies and unemployment benefits. The impact of globalisation on the different welfare programmes also varies according to the dimension of globalisation under analysis. The positive and statistically significant impact on old age pensions seems to be derived from social and political globalisation. The positive and statistically significant impact on incapacity benefits comes from the political dimension alone and the same applies to active labour market policies. In the case of family benefits, the positive and statistically significant impact comes from social globalisation alone. As for unemployment benefits, although the impact with overall globalisation is positive and statistically significant, none of the specific dimensions of globalisation presents a statistically significant effect. Additionally, although overall globalisation exerts no statistically significant impact on survivors pensions, health, housing, other social policy areas and education, political globalisation exerts a positive and statistically significant influence on survivors pensions and social globalisation exerts a positive and statistically significant influence on health spending. Political globalisation influences the highest number of social spending components (four), followed by social globalisation that influences three categories, although not the same as those for political globalisation, except for old age pensions. As for economic globalisation, although the results with total public social spending point to a positive and statistically significant impact, none of the results with the different components of social spending are statistically significant. As for the quantitative impact of the statistically significant influences, if overall globalisation increases by one point the change in a specific component of social expenditure ranges from an increase in 0.19 percentage points for old age expenditures to 0.02 percentage points for unemployment benefits. The former impacts result mainly from changes in either political or social globalisation. For old age expenditures the impact is basically the same, an increase in 0.11 percentage points from a one point change in social globalisation and an increase in 0.13 percentage points from a one point change in political globalisation. The results for the control variables remain basically unchanged, with some loss of statistical significance for certain components of social expenditure, and are available from the authors.

These findings suggest that a change in the (relative weights) type of globalisation can result in different compositions of the welfare state, which in turn will lead to different social and economic outcomes. Considering as our reference the results of the encompassing study by Cammeraat (Reference Cammeraat2020), globalisation, by leading to an increase in family benefits, will result in less poverty (the same applies to unemployment and Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs)) and inequality (the same applies to old age pensions). The author only finds a strong positive relationship with GDP growth for spending on “housing and others,” but our results do not confirm any impact of globalisation on this social programme. Crociata et al. (Reference Crociata, Agovino, Furia, Osmi, Mattoscio and Cerciello2020) concludes however that the relationship with GDP is negative for old age and unemployment benefits and positive for incapacity and family spending. In any case, globalisation has no impact on components of social expenditure that potentially have an important role on long run growth, in particular health and education spending that can increase human capital accumulation, although the influence could still happen through family related benefits and ALMPs. Interestingly, family related benefits seem to be best explained by social globalisation an indication that an increase in the perceptions of the benefits and costs of foreign welfare regimes have an impact on some categories of social spending; ALMPs in turn are mainly influenced by political globalisation. The findings concerning old age pensions indicate that they do not react only to demographics, and unemployment benefits do not depend only on economic conditions proxied by the unemployment rate. From a short run economic recovery perspective, Furceri and Zdzienicka (Reference Furceri and Zdzienicka2012) find that unemployment benefits present the greatest spending multiplier (together with health) and Ko and Bae (Reference Ko and Bae2020) conclude that ALMPs lead to higher employment rates.

Conclusion

This paper extends the analysis on the relationship between globalisation and social policy by systematically taking into account different dimensions of globalisation and their impact on social spending programmes using data for OECD countries over the period 1990–2015. The results obtained lend no empirical backing to the heralds of doom that announced the shrinking of the welfare state due to the wave of globalisation experienced since the 1980s. Our findings suggest at most that globalisation had no influence on social expenditure, although a few qualifications apply. As far as the dimensions of globalisation are concerned, social globalisation seems to be the only dimension that exerts no influence on total social expenditure. Another important finding is that components of social expenditure respond differently to globalisation, overall and in its dimensions. Old age pensions, incapacity related, family and unemployment benefits and ALMPs react positively to globalisation, which can have important implications for how globalisation affects both short and long run economic performance because of different intensities of the associated spending multipliers and depending on their relevance for the explanation of capital accumulation and productivity, the drivers of economic growth. Additionally, previous studies also show that poverty and inequality react differently to specific welfare schemes. Our results can thus help shed additional light on the varied welfare trajectories observed in different countries and help to predict with more accuracy future paths, as well as enabling a better understanding of the impact of globalisation on poverty, inequality and economic performance, with welfare programmes as the mechanisms of transmission.

Furthering our theoretical understanding of the relationship between globalisation and the welfare state, in particular with the composition of social spending, remains an open avenue for further research, contributing to moving the debate beyond preconceived ideas. The welfare state regime could also make a difference to what kind of social expenditures are affected by globalisation. We did not pursue this line of enquiry for conceptual and methodological reasons. Conceptually, because there are a number of competing welfare state typologies within the comparative social policy literature (Aspalter, Reference Aspalter2019). Additionally, some authors argue that the concept of welfare regimes describes in fact “ideal types” but in practice welfare provision also varies widely between countries belonging to the same welfare regime (Aspalter, Reference Aspalter2021). Methodologically, to the extent that country specific features of the respective welfare state arrangements remain constant over time they are taken into account through the consideration of fixed effects. Our work paves the way for future comparative studies that investigate the trajectories of social expenditure as a consequence of globalisation in individual OECD countries and examine the within-OECD differences between countries belonging to different welfare state regimes.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers and the Editors for helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Notes on Contributors

Marcelo Santos is a researcher affiliated with CeBER (Centre for Business and Economics Research). He holds a PhD in Economics and his research interests include inequality, economic growth and human capital.

Marta Simões is Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Economics of the University of Coimbra, Portugal and a researcher affiliated with CeBER (Centre for Business and Economics Research). She holds a PhD in Economics. Her principal area of interest lies in the comparative analysis and identification of the fundamental and proximate causes and consequences of varied social and economic outcomes in countries at different levels of development.

Funding

This work has been funded by COMPETE 2020, Portugal 2020 and the European Union (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-029365) and by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia I.P./MCTES, project PTDC/EGEECO/ 29365/2017 (“WISER Portugal – Welfare Intervention by the State and Economic Resilience in Portugal”) and project UIDB/05037/2020.

Data availability statement

The data used in this study was collected from publicly available sources.