1. Introduction

The prosecution of criminal suspects is an integral part of a country's justice system. Ideally, prosecutors – together with the police and judges – are central actors in implementing the rule of law. While substantial scholarly attention has been devoted to the study of the police and judges and their relevance to the rule of law, surprisingly little is known about prosecutors. This lacuna of research is not confined to the legal sciences but also extends into the economic analysis of law.Footnote 1 This is astonishing since all the institutions making up the criminal justice value chain need to work together to sustain the rule of law effectively. Prosecutors are the link between police investigations and court adjudication and have far-reaching decision-making powers over each criminal case (Luna and Wade, Reference Luna and Wade2012c: 1). In the overwhelming majority of criminal justice systems, it is their responsibility to decide whether police investigations will lead to prosecution and thus whether courts will be able to try offenders at all. Prosecutors are, hence, agenda-setters for judges, and they have been referred to as the ‘judge before the judge’ and ‘judge by another name’ (Weigend, Reference Weigend2012: 378, 389). Prosecutors formulate charges, conduct the prosecution and argue the case in court. If they disagree with the court's decision, they may typically appeal against its ruling (European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice, 2014: 4; Luna and Wade, Reference Luna and Wade2012b: xi; Tonry, Reference Tonry2013a: 1). In the wake of recent developments the importance of their independence has increased even further. In order to take the strain off overloaded court systems, many jurisdictions have shifted powers and responsibilities from judges to prosecutors. As a result, some scholars consider prosecutors to be potentially the most powerful actors in the criminal justice system (Jehle and Wade, Reference Jehle and Wade2006; Weigend, Reference Weigend2012: 383–9).

The aim of this paper is to contribute towards filling this knowledge gap. We focus on what we consider to be a centrally important factor in the proper functioning of these agencies, namely the degree to which they are independent from the other two branches of government. Although the study of judicial independence is well-established (Voigt et al. (Reference Voigt, Gutmann and Feld2015) is just one recent example), the study of the independence of prosecutors is not, despite its potential relevance for protecting the rule of law. Without this independence, the executive may exercise undue influence over prosecutors to protect government members, interest groups and supporting elites from criminal prosecution or, on the contrary, use its influence on prosecutors to repress citizens, businesses and political opposition if such behaviour promises to enhance its own goals (Weigend, Reference Weigend2012: 383–9).

In a study analysing the effects of both the de jure and the de facto independence of prosecutors on political corruption, Van Aaken et al. (Reference Van Aaken, Feld and Voigt2010: 224–5) find that these two notions of independence are negatively correlated: the greater the independence of prosecutors according to the law, the less independent they actually are (Van Aaken et al., Reference Van Aaken, Feld and Voigt2010: 210). This finding is puzzling. In their paper, Van Aaken et al. suspect that countries experiencing important governance problems (such as high corruption levels) might have been encouraged (e.g. by development aid donor countries, international organizations, etc.) to modernize their criminal procedural law leading to high levels of de jure independence but that nothing much has changed on the ground, implying low levels of de facto independence. In this paper, we take up the puzzle by enquiring more systematically into the determinants of the de facto independence of prosecutors. We carry out the first quantitative assessments of the effects of institutional differences between prosecuting agencies around the world on the actual independence of these agencies.

In our comparative analysis, Van Aaken et al.’s data on the de facto independence of prosecutors serves as our dependent variable. We analyse this data as follows: as a starting point, we apply the theoretical framework that Hayo and Voigt (Reference Hayo and Voigt2007) developed in their study on the determinants of the de facto independence of the judiciary to the procuracy. We observe that some, but not all, of the determinants of the independence of the judiciary are also among the factors that determine the independence of prosecutors. In our investigation we distinguish between factors that can be subject to policy measures and those that are largely exempt from government influence. The results of this study thus promise to be highly policy-relevant. We find that the key determinants conducive to a high level of independence are common law as legal origin, a free press and regulations granting parliamentarians immunity from prosecution.

The paper is structured as follows. We first introduce some stylized facts on the institutional differences between prosecuting agencies across countries around the world. This serves to outline the complexity involved in conducting comparative research on these agencies (section 2). We then demonstrate the necessity for our study by explaining the rising importance of prosecutors for criminal justice systems around the world (section 3). We subsequently identify the independence of prosecution agencies as a centrally important characteristic, and then proceed to analyse it from the perspective of political economy (section 4). In section 5, we discuss the possible determinants of the independence of prosecutors. Section 6 describes how this independence can be measured in a cross-country setting. Our estimation strategy and empirical results are presented in Sections 7 and 8, respectively. We conclude with a summary of how our research contributes to the study of prosecutors and formulate policy advice on how to strengthen the rule of law by better protecting the independence of these agencies (Section 9).

2. The institutional differences between prosecuting agencies

While the core functions and responsibilities of the police and judiciary are similar in all developed countries, those of prosecutors have traditionally varied fundamentally (Tonry, Reference Tonry2013a: 2–4). Comparative research on this criminal justice organization is thus challenging and this may explain why cross-national research on prosecutors is even scarcer than research on prosecutors in national settings (Luna and Wade, Reference Luna and Wade2012b: xi). Consider the following stylized examples of institutional differences between prosecuting agencies across countries around the world.Footnote 2 In countries governed by the rule of law, the organizational location of judges is generally separated from the executive and the legislature. The situation for prosecutors is more varied (European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice, 2014: 292). In some countries, prosecutors are members of the judiciary (e.g. France, Italy, Sweden), in others they are part of the executive branch of government. In the latter case, they may work for the ministry of justice (e.g. Japan), in special national or state agencies (e.g. England and Wales, Germany), in police departments (e.g. Denmark, Norway), etc. (European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice, 2014: 292–3; Tonry, Reference Tonry2013a: 14–6). Locating the prosecution agency close to the executive may improve accountability and make it easier to implement coherent law enforcement policies, but it also bears the risk of undue influence from the executive. Given that the judiciary is independent, locating the prosecution agency close to the judiciary insures its political independence, but makes it harder to implement criminal policies and to hold prosecutors accountable for their actions (Gilliéron, 2014: 314). Hence, there is a trade-off between the independence and the democratic accountability of prosecutors. If independence is too high, it is hard to hold prosecutors responsible and there is a risk that they abuse this independence to pursue their own private interests or political agenda.

Similarly, the education and career path of prosecutors may vary across countries and so does their relative salary compared to that of judges. The different ways in which prosecutors are educated and socialized may lead to different forms of prosecutorial self-perception, professional ethos and practices (Luna and Wade, Reference Luna and Wade2012a: 429). For example, it may affect the degree to which prosecutors take public and political opinions into account. In most developed countries, prosecutors are nonpartisan career public servants who are expected to make decisions independently of public and political opinions. In contrast, in the US, many chief prosecutors are elected office holders and in result, public opinion and political considerations are said to have a greater influence on their decision making (Tonry, Reference Tonry2013a: 2–3). Nevertheless, politically motivated prosecutions are relatively rare in the Western world, but some observers note that they occasionally occur (Tonry, Reference Tonry2013a: 15–16).

Prosecuting agencies differ not only in their institutional and organizational set-ups, but also more fundamentally, namely in regard to the general principles according to which they operate. In some countries, prosecutors have traditionally had to prosecute cases strictly according to the applicable rules (‘legality principle’) and have had only limited individual discretion over how to handle cases. This is true of Germany and many other continental European civil law countries. In other countries, prosecutors have broader decision-making powers (‘expediency principle’ or ‘opportunity principle’), including whether and how to prosecute a given case. This is true for the US and all other Anglo-Saxon common law countries (Tonry, Reference Tonry2013a: 7–12).

3. The rising importance of prosecutors in criminal justice

Nowadays, the fundamental differences in how national prosecution authorities operate (i.e. ‘legality principle’ versus ‘expediency principle’, see above) are diminishing. In response to an ever increasing case load,Footnote 3 policy makers have implemented measures that have led to a softening of this traditionally strict divide. The following three main policy options can be implemented to deal with overloaded criminal justice systems: (1) increase the size and funding of the entire system, (2) decriminalize less serious offences, which are thereafter, for example, dealt with under administrative rather than criminal law, and finally (3) increase the powers of the prosecution authorities to handle incoming cases more independently of judges and the court system (Jehle, Reference Jehle, Jehle and Wade2006: 5–6). The last option has been chosen by many Western countries. Jurisdictions that have adhered to the legality principle in the past have also implemented it, thus giving more discretionary powers to prosecutors.Footnote 4 As a result, in many jurisdictions around the world the importance of prosecutors in criminal justice has steadily increased (Jehle and Wade, Reference Jehle and Wade2006; Weigend, Reference Weigend2012: 383–9).

Now prosecutors do not simply act as an intermediary between the police and the courts, deciding whether or not a case that has been investigated should also be prosecuted. Their powers extend well beyond these core responsibilities. Under certain circumstances, prosecutors may be the sole decision makers to determine whether a criminal sanction will be imposed. They may also determine, or negotiate with the offender, the nature and severity of the sanction (Weigend, Reference Weigend2012: 386–9). To illustrate, consider the example of the US, where powers of prosecutors are particularly broad. Here, the vast majority of all criminal convictions (95% or more) result from plea bargaining agreements between defendants and prosecutors. In this system prosecutors – not judges – determine both the charges and the sentences to be imposed for a large majority of cases. Many other countries have broadly comparable mechanisms in place that have shifted decision-making powers from judges to prosecutors and have thus amplified prosecutors’ powers (Luna and Wade, Reference Luna and Wade2012b: xi, xvii; Tonry, Reference Tonry2013a: 5–9). The example of Germany demonstrates that prosecutorial discretion is also present in countries that have traditionally adhered to the legality principle. According to some calculations, about 90% of all cases in which the police had identified a suspect and which were thus declared as ‘resolved’ never went to court in Germany. Instead, prosecutors relied on a variety of case-ending options, the use of which is subject only to minimal external review (Weigend, Reference Weigend2012: 384–5).

In this section, we have shown how more and more powers have shifted towards prosecution agencies. To date, this shift of power from judges to prosecutors has not received much scholarly attention, possibly because of the complexity involved in comparative research on prosecution authorities.

4. The relevance of the independence of prosecutors for ensuring the rule of law

Preliminary remarks

In this section, the importance of prosecutorial independence in implementating the rule of law is discussed. Prosecutors and judges can be considered part of a single value chain producing justice: whereas prosecutors collect information on a case and represent ‘the public interest’, it is the task of the judges to question the reliability of the information provided by both suspect and prosecutor and reach a final decision based on that evidence. Due to this interplay between prosecutors and judges, the establishment of a high level of de facto judicial independence is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for ensuring that justice prevails in criminal cases. Prosecutors also need to be independent, otherwise some cases may never appear in court, relevant information will not be provided and so on. In what follows, we discuss why a government would want to infringe the independence of prosecutors and why the protection of this independence is thus crucial to the rule of law. We show that from the viewpoint of a government, it may be even more attractive to erode the independence of prosecutors than to compromise the independence of the judiciary. We argue that the former may lead to less opposition and may, hence, be less costly for government.

An executive can exercise influence on the judiciary and the prosecution agency for various reasons. Among these we can broadly distinguish between two types of objectives. First, a government may want to end a legitimate criminal proceeding against one of its members or members of the supporting elites. Second, it may want to initiate an illegitimate criminal case to tarnish the reputation of some opponent, or even wrongfully convict that individual. No matter which of these objectives the government pursues, it has various methods at its disposal. Consider incentives such as bribes, salary increases, promotions, etc. or disincentives such as salary cuts, demotions, disciplinary transfers, forced retirements, etc., to name just a few. These methods may vary in their effectiveness in producing the desired outcome and the costs that they inflict on a government, whereby the costs will be equal to the strength of the political and social opposition that these government actions will evoke.

We argue that the potential costs of administering these methods to judges are always higher than administering them to prosecuting authorities. Infringing judicial independence is a government action that is more visible and thus also more easily detectable than a comparable infringement aimed at the prosecution authority. It is therefore also likely to lead to fiercer resistance. From a government's point of view, since exercising an influence on the prosecution authority is likely to lead to comparable results at lower costs than using the same means against the judiciary it is thus an appealing option. This is illustrated by the following examples.

Ending a legitimate criminal case

Imagine a scenario where there is a legitimate criminal case, the regular prosecution of which would not be in the interest of a government. For example, a member or supporter of a government might have engaged in a criminal activity such as corruption, which was subsequently detected. Let us first examine the outcome of this scenario proceeding from the assumption that the independence of the prosecution agency is guaranteed and then alter the scenario by proceeding from the opposite assumption.

Scenario A: The independence of prosecutors is protected

In this scenario, the prosecutor would supervise and direct police investigations to detect the most incriminating evidence.Footnote 5 Once the preliminary investigation has produced sufficient evidence, the prosecutor may decide whether the case should go to trial or if she wants to choose another case-ending option that she deems adequate.Footnote 6 If she decides to go to trial, she will present the incriminating evidence, argue the case as convincingly as possible and call for a sentence that she considers appropriate. Assuming that the prosecution agency enjoys de facto independence but the judges do not, the government can stop the criminal case only once it has reached the court stage. However, from the perspective of both a criminal and a supporting government much damage has already been done by this time. The incriminating evidence is now available to a broader audience. Any infringement of judicial independence will thus become easily visible. Attempts to cover up such government actions or to mediate their consequences, for example by convincing the political and social opposition of the innocence of the criminal or hiding the outcome of the case from the public altogether, will now be challenging. Consequently, any undue influence exerted on the judge to dismiss a legitimate case once it has been brought to the court stage by an independent prosecutor will come at a high cost to the executive.

Scenario B: The independence of prosecutors is infringed

Now consider the same criminal case with modified assumptions. Assume that the executive can infringe the independence of the prosecuting agency. In this scenario, a government that aims to influence the outcome of the case would not wait until it has reached the court stage. Rather, the government would try to exert influence on the case as early as possible in the criminal justice value chain. Supposing that the government is successful, the case will never reach the court, for instance, because the prosecutor has been sufficiently unsuccessful in finding incriminating evidence, for example. The prosecutor could also choose the most favourable pretrial case-ending option available to her with the aim of letting the criminal off with no or minimal sanctions and thus prevent the case from ever being heard in court. If it turns out to be impossible to prevent the case from coming to trial, the prosecutor can still try to conceal incriminating evidence and plead for a very light sentence in court. Under these circumstances, even an independent judge would have a hard time arriving at an appropriate judgement. If the judge sentences the criminal nonetheless, the sentence is likely to be less harsh than would be commensurate. Furthermore, if the government also decides to infringe the independence of the judge, this would be substantially less costly than in a scenario in which the prosecutor is independent. Less incriminating evidence has been made public and the prosecutor's favourable presentation of the case would make it harder for the public to detect that the judge’s freedom had been infringed and the subsequent biases in her judgement. Thus, the costs resulting from infringing the independence of the prosecutors are much lower than they would have been if the prosecutors had been independent.

Initiating an illegitimate criminal case

Finally, consider a scenario where the executive does not want to end a legitimate criminal proceeding but is, rather, interested in a meritless prosecution because it intends to weaken somebody, for instance a politician of the opposition. We can again distinguish between two variants of this scenario: first, government may aim to destroy somebody's reputation. Publicizing the decision to prosecute a person may in many cases do enough damage to reach this goal and it will thus often not even be necessary to have the person convicted by a court. Hence, it will be sufficient to tinker with the independence of the prosecution agency again.Footnote 7 Second, a government may aim to have a person convicted. Here, the government needs to be able to infringe the independence of both prosecutors and judges. Infringing the independence of the judiciary alone would not lead to the desired outcome. Courts are generally passive institutions and the prosecution authority performs the function of the gatekeeper to the court system. A criminal case can thus be heard in court only once it has been passed by the prosecution authority. To obtain an unjustified judgement, the executive must therefore infringe the independence of the prosecution authority. Otherwise, a prosecutor who has objectively assessed the case of a falsely accused individual will not file charges. Additional infringement of the independence of the judiciary under these circumstances is therefore not a mandatory but an optional choice for the executive.

In this scenario, the influence of the executive on the prosecution agency works according to the same mechanisms as described above. The prosecutor may start her undertaking by producing false evidence, possibly in cooperation with the police. She could then rely on the case-ending options that are available to her to bring about an unfavourable outcome for the falsely accused individual without involving the judiciary at all. Under threat of more serious charges in court and other factors such as negative publicity, the individual may accept such an unjust outcome despite being innocent. If the case still goes to trial, the prosecutor may produce incriminating evidence and argue the case as fiercely as possible. As argued above, such behaviour on the part of the prosecutor may even deceive an independent judge, who may then falsely and unwittingly sentence an innocent person. To further augment the effectiveness of its measures, the executive can also decide to curtail the independence of the judiciary. Even though this would mean extra costs for the executive, the presence of a biased judge would further increase the probability of an unjustified and severe judgement.

Cost considerations

We can conclude that in order to achieve some of the outcomes that a government wishes to see, infringing the independence of the prosecution authority is a necessity. In cases where a government might infringe upon the independence of the judiciary, cost considerations will usually lead it to prefer targeting the independence of the prosecution agency. The decision to compromise the independence of the prosecution authority is thus motivated largely by the desire to reduce the costs connected to an infringement of the criminal justice system. The total costs that result from such a breach are made up of two elements: first, the costs resulting from carrying out the infringement. Legal and organizational factors that stand against this action will increase costs and lead to greater independence for the prosecutors. Second are the costs resulting from the possibility that the illegitimate governmental intervention will be detected and thus subsequently evoke political and social resistance. Factors likely to amplify political and social resistance to an infringement are thus factors that will bolster the independence of prosecution agencies. Based on these considerations, we derive an empirically testable hypothesis on the determinants of the independence of the prosecution authorities in section 5. Before this, we briefly present the measures for both de jure as well as de facto prosecutorial independence used in this study.

5. Measuring the independence of prosecutors

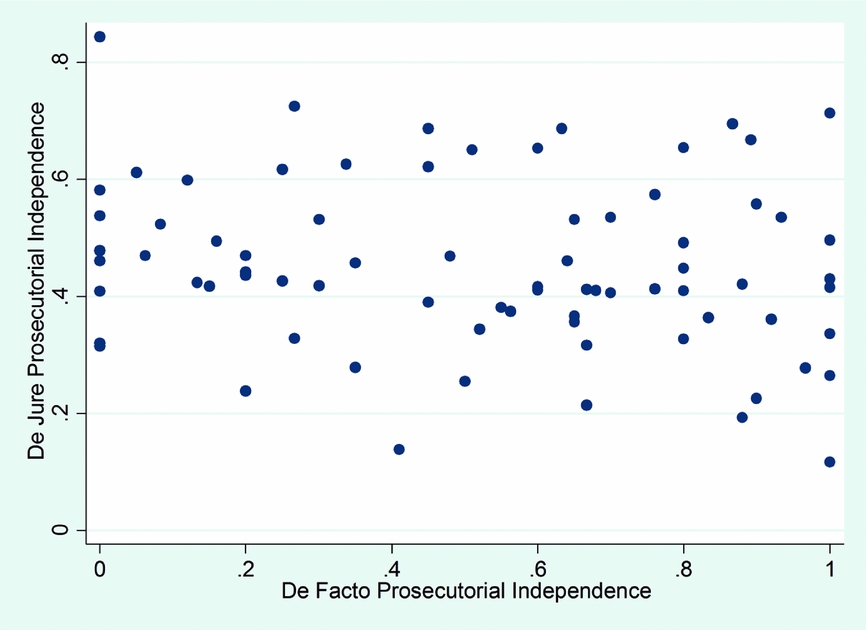

We now briefly summarize Van Aaken et al.’s (Reference Van Aaken, Feld and Voigt2010) indicators, which we employ to measure the de facto and the de jure independence of prosecutors.Footnote 8 The indicators are index variables that summarize a large variety of measures of the different aspects of this independence. The items that contribute to the de jure independence of a prosecution agency index can be found in legal documents. These include, for instance, whether the country relies on the principle of mandatory prosecution, whether prosecutors enjoy a monopoly in prosecuting criminals, whether members of the executive have the power to give instructions to prosecutors, and so on. Those items that contribute to the de facto index are various measures of the actual implementation of these legal texts such as how many prosecutors were transferred or retired against their will over a specific period. All variables used to construct the two indicators are documented in a summary fashion in the appendix to this paper. The de jure independence of prosecutor indicator is an index variable that contains up to 21 items. Within the de jure index, five overall groups, i.e. sub-indices, can be distinguished. Each of these sub-indices can take on values between 0 and 1, higher values indicating a greater degree of prosecutor independence. To assess the de facto independence, an index variable based on up to seven items was constructed. Again, each of these sub-indices can take on values between 0 and 1, higher values indicating a greater degree of prosecutor independence. As mentioned above, Van Aaken et al. (Reference Van Aaken, Feld and Voigt2010) found a weak negative correlation between the two notions of de facto and de jure independence (r = −0.214). Figure 1 shows the relationship between the de jure and de facto independence of prosecutors. In the analysis presented below, we therefore set out to enquire more systematically into the determinants of the de facto independence of prosecutors.

Figure 1. De jure and de facto independence of prosecutors

6. Factors influencing the independence of prosecutors

Introductory remarks

We have discussed the purposes for which governments may want to infringe the independence of prosecutors and what costs are associated with such infringements. We are now hypothesizing what factors prevent or at least make it less attractive for governments to conduct such infringements. We argue that governments will respect the independence of prosecutors permanently only if the costs of such infringements exceed any possible benefits. As we have explained above, these costs are made up of two elements: the costs resulting from carrying out the infringement and the costs resulting from the possibility that the infringement will be detected and subsequently evoke political and social resistance.

As a starting point for discussing the determinants of the de facto independence of prosecutors, some insights from the literature on the independence of the judiciary are helpful. Above, we have pointed out the differing scopes of responsibility but also the complex interplay between judges and prosecutors in a criminal justice system. Some of the determinants of the independence of the judiciary may be equally relevant to the independence of prosecutors and will thus be included in our analysis after due consideration. Hayo and Voigt (Reference Hayo and Voigt2007) distinguish between two types of determinants of judicial independence: factors that are not open to policy intervention, at least not in the short and medium term (e.g. the legal tradition of a country, its political system, the religious and ethnical diversity in a country, etc.) and factors that are open to policy intervention (e.g. the degree of press freedom granted, whether immunity from prosecution is granted to members of parliament, various legal regulations pertaining to the prosecution authority). Gutmann and Voigt (Reference Gutmann and Voigt2017) show that the first group plays an important role in determining the quality of the judiciary. We adopt Hayo and Voigt's differentiation for our presentation of the determinants of the independence of prosecutors.

Factors open to policy interventions

A natural starting point for explaining differences in the de facto degree of prosecutorial independence across countries is the degree of de jure independence the prosecutors enjoy according to the letter of the law. This will hence always be included on the right hand side of our models.

Press freedom

We have argued above that government actions that infringe the independence of the prosecution authority come at a cost. This cost stems from the risk that an illegitimate intervention will be detected and reported and that it may thus subsequently evoke political and social resistance. We hypothesize that the freer the press in a country, the costlier and, hence, less attractive it will be to infringe the independence of the prosecution authority. To account for the freedom of the press in our models, we use the Freedom House indicator (Freedom House, 2000; Hayo and Voigt, Reference Hayo and Voigt2007: 275). We have multiplied the indicator by −1 and it thus ranges from −100 (the least free) to 0 (the most free).

Immunity of parliamentarians

According to our theory, the executive may want to exert pressure on the prosecution agency to end a legitimate criminal case against a member of its own government or to initiate an illegitimate criminal case against the opposition. If our theory proves right, in regard to the first goal a law that protects members of parliament from prosecution should make this government action superfluous and in regard to the second goal, it should make it ineffective. Consequently, a law granting immunity to parliamentarians will make it less attractive to a government to infringe the independence of its prosecution authority and we thus hypothesize that it will increase the de facto independence of prosecutors. The variable is based on our own coding of data from various sources relating to the laws governing the immunity of parliamentarians.Footnote 9 Countries in which members of parliament are protected from prosecution are coded 1.

GDP per capita and size of the procuracy

We also include in our model a country's per capita income in 1995 as a general control variable to see whether higher income is associated with more independent prosecution agencies. The data are taken from Feenstra et al. (Reference Feenstra, Inklaar and Timmer2015) and are measured at constant 2011 national prices. GDP per capita can also be interpreted as a general proxy for state capacity. However, it is very broad and as a general robustness check we propose to replace it by the variable ‘size of the procuracy’ as a more context-specific proxy. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2004) provides data on the total number of prosecution personnel per 100,000 inhabitants.

Factors impervious to policy interventions

Polity

Following the theoretical argument we introduced above, actions that infringe the independence of prosecutors come at a cost to governments. If the independence of the prosecution authority is a value that voters embrace, they may sanction a government that acts contrary to it in their re-election decisions. However, this mechanism can only work effectively in a democratic regime. We therefore control for the level of democratization in a country using the polity indicator developed by Marshall et al. (Reference Marshall, Gurr and Jaggers2014). The variable codes countries on a scale from –10 (strongly autocratic) to +10 (strongly democratic).

Federalism

Compared to a unitary state, a federal state has an additional layer of government. In the latter political system, we thus find additional players who may have interests different from the federal government. If the federal government wants to infringe the independence of the prosecution authority, it must deal with a larger number of potential veto players and potentially also cope with more political resistance. In a federal state, we expect the cost for infringing the independence of the prosecution authority and thus also its independence to be higher than in a unitary state (Hayo and Voigt, Reference Hayo and Voigt2007: 275). We use the variable from Norris (Reference Norris2009) to control whether a country has a unitary, a federal or a hybrid form of government.

Legal origin

Feld and Voigt (Reference Feld and Voigt2003) hypothesize that the legal tradition of a country may affect judicial independence, and this may also apply to prosecutorial independence. In our regression models, we thus include the legal origin dummy variables from La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer2008). We hypothesize that, as for judicial independence, an English legal origin may provide for a legal environment that is more supportive of prosecutorial independence than a French legal origin. This implies that countries with socialist, German or Scandinavian legal origins serve as the reference group in our models.

Ethnic, religious and linguistic fractionalization

Easterly and Levine (Reference Easterly and Levine1997) were among the first to point out that ethnic diversity may cause the implementation of growth-impeding public policies. After quoting a number of possible transmission channels they show that ethnically fractionalized societies tend, indeed, to grow significantly slower than more homogeneous ones. When including measures of ethnic and religious fractionalization here, we have one specific transmission channel in mind: the more political and social opposition a society can organize, the larger will be the costs that a government must bear as a consequence of infringing the independence of prosecutors. And the ability to organize political opposition and to overcome the problem of collective action might depend on how fractionalized a country is. To take this possibility into account, we rely on three fractionalization variables made available by Alesina et al. (Reference Alesina, Devleeschauwer, Easterly, Kurlat and Wacziarg2003), who distinguish between ethnic, religious and linguistic fractionalization. Fractionalization is at its maximum, if every member of society follows his or her own religion, etc. Montalvo and Reynal-Querol (Reference Montalvo and Reynal-Querol2005) argue that polarization could in this regard be even worse than fractionalization. Polarization is at its maximum when society consists of two (religious) groups both making up exactly half of society. As a robustness check (not shown here), we also rely on their variables for religious and ethnic polarization (they do not provide an indicator of linguistic polarization). Table 1 displays summary statistics of all the key variables introduced above.

Table 1. Summary statistics

Note: The following are dummy variables: English and French ‘legal origin’ and ‘immunity of parliamentarians’. Federalism is a categorical variable consisting of the categories ‘unitary states’, ‘hybrid unions’ and ‘federal states’. ‘Real GDP per capita’ is a country's expenditure-side real GDP per capita at current PPPs (in 2011 US dollars) for the year 1995.

7. Estimation strategy

We analyse the data on the de facto independence of prosecutors in two steps. In our five models we broadly follow the modelling approach that Hayo and Voigt (Reference Hayo and Voigt2007) developed for their study on the determinants of de facto judicial independence. Each of the models presented below thus differs in regard to the set of explanatory variables employed.

Of the 76 countries in our dataset, two have missing values for some of the independent variables. A total of 74 countries were thus used to identify model 1. An OLS regression model was employed. The model has an R-square value of 0.29, indicating an acceptable fit of the model.Footnote 10

8. Results

Table 2 contains five models with de facto prosecutorial independence as the dependent variable. In none of the five models is the coefficient of ‘de jure independence’ statistically significant.

Table 2: The independence of prosecutors models with the ‘de jure independence’ index

Note: The dependent variable is ‘de facto independence of prosecutors’. The reference category for ‘Federalism’ is ‘unitary states’, and the reference category for ‘legal origin’ is ‘socialist, German or Scandinavian’.

*** Significant at 0.1%, ** significant at 1%, * significant at 5%, † significant at 10%.

Our results show that a free press is positively associated with the ‘de facto independence of prosecutors’. For example, model 1 predicts that a 10-point increase in the press freedom index leads to a 0.10-point rise in the ‘de facto independence of prosecutors’.Footnote 11 This finding supports our theoretical argument that a government's decision to infringe the independence of prosecutors is based primarily on cost considerations. A free press amplifies the costs that may result from social and political resistance following an infringement of prosecutorial independence and thus make such behaviour less attractive (see above). One way to strengthen the independence of prosecutors is thus to implement measures that allow for free media coverage on a country's criminal justice system.

In models 3, 4 and 5, the coefficients of the variable ‘immunity of parliamentarians’ are statistically significant. After controlling for all other variables, model 3 predicts an average increase in ‘de facto independence of prosecutors’ by 0.23 points when a country grants immunity to parliamentarians. We argue that parliamentary immunity constrains the benefits government can possibly reap from infringing on the independence of prosecutors. In the presence of parliamentary immunity, a government cannot abuse the prosecution authority to initiate illegitimate criminal cases against the opposition and this provision also makes it superfluous to end a legitimate criminal case against a member of its own government. A law that protects members of parliament from prosecution therefore also protects the prosecution authority from governmental infringements.

In our models 1–5, the coefficients of the variable ‘legal origin: English’ are statistically significant, in models 3–5 this also holds true for the coefficients of the variable ‘legal origin: French’. Thus, there is evidence that countries of common law legal origin perform better in ensuring the independence of prosecutors than countries from the omitted category that is made up of countries belonging to the socialist, German, and Scandinavian legal families. For example, model 1 predicts that on average, countries of common law legal origin do 0.24 points better on the ‘de facto independence of prosecutors’ index than the reference category. Interestingly, French legal origin countries also do somewhat better than the countries belonging to the omitted legal families.

Finally, per capita income is positively associated with de facto prosecutorial independence. ‘GDP per capita’ can also be interpreted as a general proxy for state capacity. However, it is very broad and furthermore also highly and significantly correlated with ‘press freedom’. We therefore propose to use the variable ‘size of the procuracy’ as a more context-specific proxy. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2004) provides data on the total number of prosecution personnel per 100,000 inhabitants. Unfortunately, even after imputing data using previous and later surveys from the same source, the variable remains patchy and when used to replace ‘GDP per capita’ as a control variable, the number of observations in our models decreases further. We nevertheless used this variable to run a general robustness check (see model 5) and found that our results remained stable. When controlling for the number of prosecution personnel, the direction and strength of the effects that we observe in our models are largely unaffected.

9. Conclusions

Prosecutors are potentially the most powerful actors in a country's criminal justice system. To date, quantitative comparative research on prosecutors has been rare. In this study, we set out to identify the factors that determine the independence of prosecuting agencies worldwide. We find that countries of common law legal origin perform better in ensuring the independence of prosecutors than countries of socialist, German or Scandinavian legal origin. As this factor cannot easily be influenced by policy-making, this finding is mainly of academic interest. However, there are also several factors that affect the independence of prosecutors that are susceptible to policy interventions. According to our empirical analysis, freedom of the press is a key guarantor of prosecutorial independence. Furthermore, a law granting immunity to parliamentarians is another factor that contributes to the de facto independence of prosecutors.

What are the policy implications of these findings for countries in which the rule of law and criminal justice is endangered? First, these countries should aim to implement transparency policies for all institutions in the criminal justice value chain, and particularly for the procuracy. We expect comprehensive and prompt disclosure of information relating to the prosecution or dismissal of cases with a political dimension to allow the press and any other social and political organization to better report on illegitimate dealings between the executive and the prosecution authority. In terms of our economic analysis of the independence of prosecutors, transparency policies increase the costs that the executive must bear for infringing this independence. In the presence of such policies, ending a legitimate criminal case or initiating an illegitimate criminal case is more likely to lead to social and political opposition by civil society. Second, we have shown that laws preventing the prosecutions of members of parliament also strengthen the independence of the prosecution authority and may thus benefit the rule of law and criminal justice. Parliamentary immunity makes it superfluous for the executive to infringe the independence of the prosecution authority in order to protect a member of government from prosecution because such a case cannot be initiated in the first place. An immunity law also greatly increases the costs of initiating an illegitimate criminal case against a politician of the opposition. In the presence of such a law, this action will require a prior lift of the immunity of the targeted politician. Depending on the actual implementation of the immunity law, this lift usually follows a predefined, transparent procedure. It will thus lead to the prompt disclosure of comprehensive information on the case. As for our first policy recommendation, this will facilitate press coverage of the case and consequently social and political opposition supporting the independence of prosecutors is more likely to occur.

This paper can only constitute a very first step in closing the pertinent knowledge gap regarding the factors determining the de facto independence of prosecution agencies. Due to data constraints, the analysis here presented rely exclusively on a cross-section. To capture the dynamics in the development of prosecutorial independence over time, drawing on time series is definitely a desideratum.

In this paper, we summarized the specific interests of government in prosecutorial behaviour by using two paradigmatic cases: in the first case, government has an interest in preventing the prosecution of those who are on its side but have committed a crime. Formulated differently: government has an interest in false negatives or type 2 errors. In the second case, government has an interest in having innocent actors, such as regime critics, prosecuted. Here, the government is interested in seeing false positives or type 1 errors.

Are there governments who are more active in pursuing a particular kind of error over the other kind? What are the factors determining that choice? One way to learn about this is by case study research. Sometimes, indicting a public figure is sufficient to destroy her reputation. But sometimes, this is not enough and a court decision is necessary. In such situations, the outcome is determined by the interplay between the prosecutors and the judges. Modelling their interactions explicitly is, hence, also a desideratum.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jerg Gutmann, Eric Langlais, Stephan Michel, participants of workshops where we presented this paper (the International Conference on the Economic Analysis of Litigation 2016 in Montpellier; the Annual Meeting of the German Law and Economics Association 2016 in Budapest; and the Annual Conference of the European Association of Law and Economics 2016 in Bologna) and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. All errors are the authors’ responsibility.

Appendix: Single components entering the indices of prosecutorial independence

Here, we document the single components that went into the construction of both the de jure as well as the de facto indicator. Please note that the original questionnaire asked these questions in a different order and also that it did not contain any of the headlines used here to make the structure of the de jure indicator more visible. For information on how the variables were coded, please turn directly to Van Aaaken et al. (Reference Van Aaken, Feld and Voigt2010).

De jure prosecutorial independence

General traits

(1) Is the office of state prosecutor (a) mentioned in the constitution? (b) mentioned in the law? (c) mentioned somewhere else?

(2) Are formal qualification prerequisites for being appointed as a prosecutor less demanding than those applying to judges? (a) yes; (b) no.

(3) Removal of state prosecutors is (a) easier? (b) the same? (c) more difficult than removing judges from office?

(4) Is there an impersonal rule that allocates incoming cases to specific prosecutors? (a) yes; (b) no.

Personal traits

(5) Do high-level prosecutors enjoy tenure (a) for life or until retirement? (b) for a fixed term of ___ years, (b-i) with renewability? (b-ii) without renewability? (c) other, namely ___?

(6) How are high-level prosecutors nominated/appointed/elected? (a) High-level prosecutors are nominated and appointed by one or more members of the executive; (b) high-level prosecutors are nominated by one or more members of the executive and are elected by parliament (or a committee thereof); (c) high-level prosecutors are nominated by one or more members of the executive and are elected by the judiciary; (d) high-level prosecutors are nominated and elected by parliament (or a committee thereof); (e) high-level prosecutors are nominated by parliament (or a committee thereof) and are elected by one or more members of the executive; (f) high-level prosecutors are nominated by parliament (or a committee thereof) and are elected by the judiciary; (g) high-level prosecutors are nominated and elected by the judiciary; (h) High-level prosecutors are nominated by the judiciary and are appointed/elected by one or more members of the executive; (i) high-level prosecutors are nominated by the judiciary and are elected by parliament (or a committee thereof); (j) high-level prosecutors are nominated by the judiciary, the legislature, or the executive and are elected by actors not representing any government branch (academics, the public at large); (k) high-level prosecutors are elected by general elections. (l) high-level prosecutors are elected by still a different procedure, namely ___.

(7) Low-level prosecutors can be promoted by (a) high-level prosecutors; (b) the minister of justice; (c) other members of the executive.

(8) High-level prosecutors can be removed from office (a) only by judicial procedure; (b) by decision of one or more members of the executive; (c) by decision of parliament (or a committee thereof); (d) by joint decision of one or more members of the executive and of parliament (or a committee thereof); (e) other.

(9) Low-level prosecutors can be removed from office (a) only by judicial procedure; (b) by decision of one or more members of the executive; (c) by decision of parliament (or a committee thereof); (d) by joint decision of one or more members of the executive and of parliament (or a committee thereof); (e) other. The reasons are (e.g. disciplinary offence): ___.

(10) Do low-level prosecutors enjoy tenure (a) for life or until retirement? (b) for a fixed term of ___ years, (b-i) with renewability? (b-ii) without renewability? (c) other, namely ___?

(11) Do criminal law judges enjoy tenure (a) for life or until retirement? (b) for a fixed term of ___ years, (b-i) with renewability? (b-ii) without renewability? (c) other, namely ___?

Formal traits

(12) Does the head of the procuracy have the power to give instructions to prosecutors (a) with regard to specific cases? (b) by issuing general guidelines? (c) not at all?

(13) Do members of the executive have the power to give instructions to prosecutors (a) with regard to specific cases? (b) by issuing general guidelines? (c) not at all?

(14) Can an investigation be reallocated to another state prosecutor against the will of the hitherto investigating state prosecutor without due reason? (a) yes; (b) no.

(15) Are the possibilities for reallocation enumerated by law? (a) yes; (b) no; they are ___.

Monopoly

(16) Is the power to initiate court proceedings with regard to crimes (a) confined to state prosecutors only? (b) also available to others, namely (b-i) the police? (b-ii) directly concerned individuals? (b-iii) others (such as associations), namely ___?

(17) Prosecutorial decisions are subject to review by the judiciary. Does the judiciary have the competence to (a) review the charges brought by the prosecutor? (b) review the decision to prosecute a certain crime? (c) review the decision not to prosecute a certain crime due to legal or factual deficiencies? (d) review the use of the opportunity principle by the prosecutors?

Discretion

(18) Is the principle of mandatory prosecution (a) mentioned in the constitution? (b) mentioned in the law? (c) mentioned in precedent/court decisions? (d) not part of the legal system?

(19) Please answer this question only if mandatory prosecution is the pertinent legal principle in your country. Are exceptions – due to the opportunity principle – enumerated (a) in the constitution? (b) in the law? (c) in precedent/court decisions?

De facto prosecutorial independence

(20) In the decade from 1991 to 2000, approximately ___ prosecutors were forced to retire against their will.

(21) In the decade between 1991 and 2000, prosecutors have been removed against their will approximately ___ times.

(22) Since 1960, the laws relevant for the prosecution of crimes committed by members of government have been changed (a) 0 times, (b) 1 or 2 times, (c) 3 or 4 times, (d) 5 or 6 times, (e) 7 or 8 times, (f) more than 8 times.

(23) Since 1960, the income of prosecutors has remained at least constant in real terms: (a) yes; (b) no.

(24) Since 1960, the budget of state prosecutorial offices has remained at least constant in real terms: (a) yes; (b) no.