Introduction

Mitochondria are involved in respiratory metabolism in most eukaryotes but those from the male parent rarely enter or persist in the zygote, and thus mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) has been used as genetic marker for tracing the genetic history of an individual or a particular group of related individuals through maternal lineages in almost all metazoans (Le et al., Reference Le, Blair, Agatsuma, Humair, Campbell, Iwagami, Littlewood, Peacock, Johnston, Bartley, Rollinson, Herniou, Zarlenga and McManus2000, Reference Le, Blair and McManus2002; Agatsuma et al., Reference Agatsuma, Iwagami, Sato, Iwashita, Hong, Kang, Ho, Su, Kawashima and Abe2003; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Mo, Zou, Weng, Lin, Xia and Zhu2009). However, there is limited information on the genetic variation in populations of some important parasite groups from China, such as the diphyllobothriid and taeniid cestodes infecting animals and humans.

Parasitic cestodes are harboured, as adult cestodes, in the small intestine of vertebrates, and are often transmitted in the bodies of various animals as juveniles, including members which can infect terrestrial mammals (Wickstro et al., Reference Wickstro, Haukisalmi, Varis, Hantula and Henttonen2005). The larval stage of the cestodes mentioned may develop in the cerebrum, central nervous system, muscles or the liver of specific intermediate mammalian hosts (González et al., Reference González, Villalobos, Montero, Morales, Sanz, Muro, Harrison, Parkhouse and Gárate2006; Escobedo et al., Reference Escobedo, Romano and Montor2009; Raccurt et al., Reference Raccurt, Agnamey, Boncy, Henrys and Totet2009). Spirometra erinaceieuropaei, Taenia multiceps and Taenia hydatigena are three such cetodes with a worldwide distribution, having significant economic impact (Ngowi et al., Reference Ngowi, Kassuku, Maeda, Boa and Willingham2004; Dalimi et al., Reference Dalimi, Sattari and Motamedi2006; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Qiu, Zhao, Xu, Yu and Zhu2006; Gauci et al., Reference Gauci, Vural, Oncel, Varcasia, Damian, Kyngdon, Craig, Anderson and Lightowlers2008; Sissay et al., Reference Sissay, Uggla and Waller2008; Dai et al., Reference Dai, Li, Li, Liu, Liu, Liu, He, Tan, Lin, Liu and Zhu2009). Also, S. erinaceieuropaei and T. multiceps also have public health concerns, because they can occasionally infect humans and cause serious diseases (Benifla et al., Reference Benifla, Barrelly, Shelef, El-On, Cohen and Cagnano2007; Okamoto et al., Reference Okamoto, Iseto, Shibahara, Sato, Wandra, Craig and Ito2007).

DNA sequencing is relatively inexpensive and efficient for analysing genetic variation and population genetic studies (Li et al., Reference Li, Lin, Song, Sani, Wu and Zhu2008). Sequence variability has been examined in the cox1 (cytochrome c subunit 1) and the nad1 (NADH dehydrogenase I) mitochondrial genes for the distinction of species and strains of other cestodes. For instance, earlier studies using cox1 and nad1 sequences helped to establish the phylogenetic relationships of the genus Taenia (Gasser et al., Reference Gasser, Zhu and McManus1999; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Hu, Jones, Allsopp, Beveridge, Schindler and Gasser2009). Within the genus Taenia, sequence variation in mtDNA has been used to distinguish species and genotypes (Bowles & McManus, Reference Bowles and McManus1994; Gasser & Chilton, Reference Gasser and Chilton1995; Okamoto et al., Reference Okamoto, Bessho, Kamiya, Kurosawa and Horii1995; Nejad et al., Reference Nejad, Mojarad, Nochi, Harandi, Cheraghipour, Mowlavi and Zali2008). However, there is only limited information on genetic variation among populations of cestodes of socio-economic importance from China.

The objectives of the present study were to examine sequence variability in mitochondrial cox1 and nad4 genes and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) rDNA regions, among S. erinaceieuropaei, T. multiceps and T. hydatigena from different endemic regions in China. Based on the pcox1 sequences, the phylogenetic relationships among the three cestodes were also reconstructed.

Materials and methods

Parasites and isolation of genomic DNA

The parasite species, with their sample codes, number of samples, host species and geographical origins are listed in table 1. Total genomic DNA was extracted from individual samples by sodium dodecyl sulphate/proteinase K treatment, column-purified (Wizard™ DNA Clean-Up, Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) and eluted into 50 μl water according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Table 1 Sample codes, geographical origins and GenBank accession numbers of Spirometra erinaceieuropaei (from dogs), Taenia hydatigena (from dogs) and Taenia multiceps (from sheep).

Enzymatic amplification

A portion of the cox1 gene (pcox1) was amplified with primers JB3 and JB4.5 (Bowles et al., Reference Bowles, Blair and McManus1992), the ITS with primers BD1 and BD2, NC5 and NC2 (Zhu et al., 1999; Kralova et al., Reference Kralova, Hanzelova, Scholz, Gerdeaux and Spakulova2001), and part of the nad4 gene (pnad4) with primers ND4F and ND4R (table 2). The primer sets for nad4 genes were designed by the present authors based on well-conserved sequences in many distantly related taxa. These primers were synthesized on a Biosearch Model 8700 DNA synthesizer (Shanghai, China). Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) (25 μl) were performed in 10 mm Tris–HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mm KCl, 4 mm MgCl2, 200 μm of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 50 pmol of each primer and 2 U Taq polymerase (Takara) in a thermocycler (Biometra) under the following conditions: after an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, then 94°C for 30 s (denaturation); 55°C (for pcox1 and ITS) or 57°C (for pnad4) for 30 s (annealing); 72°C for 30 s (extension) for 36 cycles, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min (final extension). These optimized amplification conditions for the specific and efficient amplification of individual DNA fragments were obtained after varying annealing and extension temperatures. One microlitre (5–10 ng) of genomic DNA was added to each PCR reaction. Samples without genomic DNA (no-DNA controls) were included in each amplification run, and in no case were amplicons detected in the no-DNA controls (not shown). Five-microlitre samples of each amplicon were examined by 0.8% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis to validate amplification efficiency. PCR products were sent to Sangon Company (Shanghai, China) for sequencing from both directions.

Table 2 Sequences of primers used to amplify a portion of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene (pcox1), NADH dehydrogenase subunit 4 (pnad4) and the nuclear internal transcribed spacers (ITS) from Spirometra erinaceieuropaei, Taenia hydatigena and Taenia multiceps.

Sequence analysis and phylogenetic reconstruction

Sequences of the two mitochondrial genes and the ITS were separately aligned using the computer program Clustal X 1.83 (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Gibson, Plewniak, Jeanmougin and Higgins1997). Pairwise comparisons were made of the level of sequence differences (D) among and within the species using the formula D = 1 − (M/L), where M is the number of alignment positions at which the two sequences have a base in common, and L is the total number of alignment positions over which the two sequences are compared (Chilton et al., Reference Chilton, Gasser and Beveridge1995).

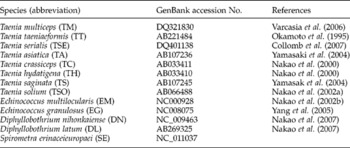

Representative samples whose cox1 sequences were available in this study were used for phylogenetic analyses. Three methods, namely neighbour joining (NJ), maximum likelihood (ML) and maximum parsimony (MP), were used for phylogenetic reconstructions. Standard unweighted MP was performed using package Phylip 3.67 (Felsenstein, Reference Felsenstein1995). NJ analysis was carried out using the Dayhoff matrix model implemented by MEGA 4.0 (Tamura et al., Reference Tamura, Dudley, Nei and Kumar2007), and ML analysis was performed using PUZZLE 4.1 under the default setting (Strimmer & Haeseler, Reference Strimmer and Haeseler1996). The consensus tree was obtained after bootstrap analysis, with 1000 replications for NJ and MP trees, and 100 for the ML tree, with values above 50% reported. The phylogenetic relationship among cestodes was performed using the sequences of 13 cestode species (table 3) as ingroup plus the three mtDNA sequences obtained in the present study, using one ascaridoid species (Ascaris suum, GenBank accession number NC_001327) as the outgroup, based on the sequences of cox1. Phylograms were drawn using the Tree View program version 1.65 (Page, Reference Page1996).

Table 3 Information about sequences of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene (cox1) of different cestodes retrieved from GenBank and used for phylogenetic study.

Results and discussion

Genomic DNA was prepared from a total of 23 individual cestodes (13, 2 and 8 samples representing S. erinaceieuropaei, T. multiceps and T. hydatigena, respectively). Amplicons of pcox1, ITS and pnad4 (approximately 450 bp, 1200 bp and 700 bp, respectively) were amplified individually and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis. For each mtDNA region, no size variation was detected on agarose gel among any of the amplicons examined (not shown).

In order to examine sequence differences in the two mtDNA regions and the ITS among the three cestode species and to assess the magnitude of nucleotide variation in the two mtDNA regions and ITS within a species, all amplicons of pcox1, ITS and pnad4 representing different species were sequenced. The sequences of pcox1, ITS and pnad4 were 334 bp, 1120–1260 bp and 614 bp in length, respectively. The A+T contents of the sequences were 62.3–63.2% (pcox1), 46.1–46.4% (ITS) and 69.1–71.3% (pnad4), respectively. While the intra-specific sequence variations within each of the tapeworm species were 0–0.7% for pcox1, 0–1.7% for pnad4 and 0.1–3.6% for ITS, the inter-specific sequence differences were significantly higher, being 12.1–17.6%, 18.7–26.2% and 31–75.5%, for pcox1, pnad4 and ITS, respectively. This result was consistent with that of previous studies (Gasser et al., Reference Gasser, Zhu and McManus1999).

For pcox1 and pnad4, intra-specific nucleotide variation was related mainly to changes at the third codon position, while fewer changes were detected at the first or second codon positions (table 4), consistent with results of other organisms (Li et al., Reference Li, Lin, Song, Sani, Wu and Zhu2008; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Mo, Zou, Weng, Lin, Xia and Zhu2009). For example, the number of intra-specific variations for S. erinaceieuropaei were 1, 3 and 4 for the first, second and third positions for cox1; and 2, 3 and 4 for nad4, respectively. Intra-specific nucleotide variations represented transitions (A ↔ G or C ↔ T; n = 5 for pcox1 and n = 6 for pnad4), transversions (A ↔ C, A ↔ T, C ↔ G, and/or T ↔ G; n = 2 for pcox1 and n = 3 for pnad4).

Table 4 Number and position of codon variations in the sequences of cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene (pcox1) and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 4 (pnad4) sequences within Spirometra erinaceieuropaei, Taenia hydatigena and Taenia multiceps.

a The first codon position of each sequence was determined in relation to that of S. erinaceieuropaei (GenBank NC_ 011037), T. multiceps (FJ495086) and T. hydatigena (FJ518620).

Length polymorphism in the simple sequence repeat (SSR) was found among individual ITS sequences. The sequence variability occurred in association with four different microsatellite sequences. The intra-specific variation in the length of the S. erinaceieuropaei, T. multiceps and T. hydatigena sequences was due to the deletion/insertion of a three-nucleotide (CTG)n repeat extending from positions 60 to 75 in the ITS-1, and a two-nucleotide (GT)n repeat extending from positions 280 to 290 in the ITS-1, respectively. The deletion/insertion of a (TGG or CGG)n repeat extending from positions 882 to 888 in the ITS-2, and a six-dinucleotide (TGGCGG)n repeat extending from positions 820 to 840 in the ITS-2, respectively, was consistent with previous reports of the (SSR) polymorphisms for parasitic cestodes (van Herwerden et al., Reference van Herwerden, Gasser and Blair2000; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Nie, Zhang, Wang and Yao2002; Foronda et al., Reference Foronda, Casanova, Martinez, Valladares and Feliu2005). These microsatellite sequences have been widely used as genetic markers for the study of population genetic structure, although their actual function is not quite clear (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Nie, Zhang, Wang and Yao2002).

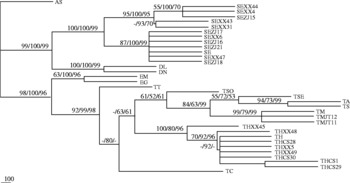

The sequences of pcox1 representing cestode species were aligned over a consensus length of 334 bp. Topologies of all trees inferred by different methods (MP, ML, NJ) with different building strategies and/or different distance models were identical or similar, with only a small difference in bootstrap values (fig. 1). The phylogenetic tree consisted of two large clades: parasites of the genus Diphyllobothrium were sister to the S. erinaceieuropaei, and the order Cyclophyllidea was in the other clade. In the clade of the order Cyclophyllidea, parasites of the genus Echinococcus were sister to the genus Taenia. Taenia multiceps and T. hydatigena were more closely related to the other members of the genus Taenia, consistent with results of previous classifications based upon their morphological and molecular datasets (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Vallejo, Mossie, Ortiz, Agabian and Flisser1995; Gasser et al., Reference Gasser, Zhu and McManus1999; Mayta et al., Reference Mayta, Talley, Gilman, Jimenez, Verastegui, Ruiz, Garcia and Gonzalez2000; Okamoto et al., Reference Okamoto, Iseto, Shibahara, Sato, Wandra, Craig and Ito2007).

Fig. 1 Phylogenetic relationship among the examined cestode species inferred by maximum parsimony (MP), maximum likelihood (ML) and neighbour joining (NJ) analyses based on mitochondrial cox1 sequences, using one ascaridoid species (Ascaris suum (AS)) as outgroup. The numbers along branches indicate bootstrap values resulting from different analyses in the order: MP/ML/NJ. Values lower than 50 are given as ‘-’.

In conclusion, genetic variability among S. erinaceieuropaei, T. hydatigena and T. multiceps isolates from different endemic regions in China were revealed by sequences of mitochondrial cox1 and nad4 genes and ITS rDNA, with higher variation in ITS than in nad4 and cox1. The results of the present study also have implications for the diagnosis and control of cestode infections in animals and humans.

Acknowledgements

Project support was provided in part by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No. 10JJ6049) to R.S.D., and the State Key Laboratory of Veterinary Etiological Biology, Key Laboratory of Veterinary Parasitology of Gansu Province, Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences to X.Q.Z.