Introduction

The crucian carp Carassius carassius (L.) is a freshwater cyprinid fish, native to the British Isles (Wheeler, Reference Wheeler1977, Reference Wheeler2000). Despite widespread movements of this fish to support angling and the tolerance of the species to varied environmental conditions (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Shelley, Harding, McLean, Gardiner and Peirson2004), crucian carp remain discretely distributed in England (Wheeler, Reference Wheeler1977, Reference Wheeler2000). In recent years, concern has grown due to a perceived decline in the number of wild crucian carp populations (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Wheeler and Wellby1998; Wheeler, Reference Wheeler2000; Häenfling et al., Reference Häenfling, Bolton, Harley, Carvalho and Pierson2005). According to Tarkan et al. (Reference Tarkan, Copp, Zieba, Godard and Cucherousset2009) the crucian carp is becoming an increasingly threatened freshwater fish species in England and Wales. Reasons for this apparent decline include hybridization, competition and loss of preferred habitat (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Wheeler and Wellby1998; Häenfling et al., Reference Häenfling, Bolton, Harley, Carvalho and Pierson2005). This has emphasized the need to protect crucian carp populations and limit further pressures upon this vulnerable species (Wheeler, Reference Wheeler2000; Häenfling et al., Reference Häenfling, Bolton, Harley, Carvalho and Pierson2005; Copp et al., Reference Copp, Warrington and Wesley2008).

Philometroides sanguineus (Rudolphi, 1819) is a parasitic nematode that infects fish of the genus Carassius. The life cycle of this parasite is seasonal and involves a free-living copepod intermediate host (Yashchuk, Reference Yashchuk1971, Reference Yashchuk1974). Fish become infected by ingesting such copepods. Philometroides sanguineus is believed to be a non-native species to Britain and was first recorded in England in 1982 following parasitological examinations of crucian carp from a farm pond in Essex (J. Moore & J. Chubb, pers. comm.). Infected crucian carp have since been recorded from a fish farm in southern England and eight stillwater fisheries (Environment Agency, unpublished). The literature suggests that nematodes of the genus Philometroides, including P. sanguineus, can be pathogenic, causing disease in both wild and cultured fish populations (Vasilkov, Reference Vasilkov1967; Vismanis & Nikulina, Reference Vismanis and Nikulina1968; Uhazy, Reference Uhazy1978; Schäperclaus et al., Reference Schäperclaus, Kulow and Schreckenbach1991; Yu et al., Reference Yu, Wang, Feng, Wu and Wang1993; Moravec, Reference Moravec1994, Reference Moravec2004a; Moravec & Cervinka, Reference Moravec and Cervinka2005). However, published information on P. sanguineus is relatively sparse and confusing. Many early records of the parasite are plagued by morphological and taxonomic inaccuracies (Moravec, Reference Moravec1971, Reference Moravec1994, Reference Moravec2004b; Vismanis & Yukhimenko, Reference Vismanis and Yukhimenko1974) and a large proportion of information is confined to the Russian and Asian literature, a situation that raises difficulties with translation and interpretation. Furthermore, lesions caused by the parasite have not been described and observations of infections in wild fish populations are fragmented. This has limited understanding of the pathogenic importance of this parasite to crucian carp fisheries. During a recent review of drancunculoid nematodes, Moravec (Reference Moravec2004a) stated that studies were urgently required to progress understanding of these parasitic worms.

This paper details the pathological changes caused by P. sanguineus to wild crucian carp. Particular attention is given to the influence of seasonality upon parasite development and corresponding tissue damage within infected fish.

Materials and methods

Fish sample collection

Material for parasitological and histopathological examinations was obtained from six samples of crucian carp obtained between 2003 and 2005. These included five stillwater fisheries and a single fish farm, located in the south-east, south-west and midlands regions of England (site details withheld for confidentiality). Samples comprised between 30 and 84 crucian carp and were obtained in the months of February, April, May, September, October and December. Although sampling effort focused on crucian carp, a single common carp × crucian carp hybrid was included in the December sample. All fish were captured by seine netting, transported live to holding facilities at the Environment Agency, Brampton and maintained in 200-litre holding tanks prior to examination.

Parasitological examinations

Fish were killed by lethal anaesthesia (immersion in 5% w/v benzocaine solution), measured (fork length), weighed and examined for gross abnormalities. Scales were taken from each fish to confirm age. Detailed parasitological examinations were conducted to establish location within the host, state of development and parasite sex. These included high-power microscopic examinations of the liver, kidney, spleen, swim-bladder, caudal musculature and intestinal tract. Particular attention was paid to the presence, location and lesions caused by post-copulated female nematodes, due to their large size and seasonal migrations within infected fish (Moravec, Reference Moravec1994).

A few nematodes from each site were examined to confirm species identification. These were fixed in Berland's fluid for 1 h, transferred to 80% ethanol and cleared in beechwood creosote. Voucher specimens of male, unfertilized female and gravid female P. sanguineus were deposited in the Natural History Museum, London (accession number NHMUK 2011.1.11.1–9). Nematodes representative of notable stages of development were measured following removal from host tissues. Due to the priority of establishing histopathological changes, only very small numbers of parasites were measured in the September, October and April samples. The reproductive status of female nematodes was also assessed by looking at the state of development of larvae within the uterus.

Histopathological studies and scanning electron microscopy

Tissues for histopathological examination were fixed in either 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) or Bouin's fixative. These were trimmed, dehydrated in alcohol series, cleared and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections (thickness 5 μm) were stained using Mayer's haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined microscopically for pathological changes. Tissues for scanning electron microscopy were fixed in 10% NBF, dehydrated in a graded alcohol series, critically point dried in CO2, sputter-coated with gold and viewed with a Jeol Scanning Electron Microscope.

Results

Prevalence and intensity of P. sanguineus infection

In the six samples of crucian carp examined, prevalence of female P. sanguineus ranged between 12.8 and 27.5%, with intensity of infection between 1 and 8 nematodes per host (mean intensity 1.1–2.7 worms) (table 1). The heaviest infection recorded during the study comprised six female nematodes located in the tail and two in the dorsal fin of a crucian carp measuring 153 mm (aged 3+years). The smallest infected fish examined was 54 mm long (aged 1+years) and harboured a single female nematode in the tail. Philometroides sanguineus was recorded in crucian carp between 1+and 5+years. At no time during the study were any crucian carp fry found to harbour P. sanguineus infection. A single gravid female P. sanguineus was also recorded in the common carp × crucian carp hybrid.

Table 1 Sample size and infection levels of P. sanguineus in crucian carp from six sites in England between 2003 and 2005.

Detection and seasonal development of P. sanguineus

Philometroides sanguineus followed a seasonal cycle of development and reproduction in crucian carp populations sampled in England. Male and female nematodes also exhibited clear sexual dimorphism, which was an important influence on parasite detection within infected fish. Adult male P. sanguineus were recorded on the kidney and serosal surface of the swim-bladder (fig. 1a). These nematodes were thread-like, measured 2–3 mm in length and possessed a round head, smooth cuticle and conspicuous yellow-orange spicules. The presence of male nematodes on the swim-bladder at all times of year, combined with the occasional detection of degenerate nematodes in the same location, suggested that male parasites did not undergo further tissue migrations. A small number of unfertilized female nematodes were also recorded on the swim-bladder surface. These transparent nematodes possessed blunt rounded ends and measured approximately 2.5 mm.

Fig. 1 (a) Two adult male Philometroides sanguineus on the swim-bladder of Carassius carassius (scale bar = 1 mm). (b) Adult crucian carp infected with two female P. sanguineus, showing conspicuous red-coloured nematodes positioned in a U-shape between caudal fin rays (arrows) (scale bar = 10 mm). (c) Single female P. sanguineus within the dorsal fin of C. carassius. The head and tail (*) of the nematode are directed towards the fin tip while the body, which overlaps itself (arrow), extends into the dorsal musculature (scale bar = 1 mm). (d) Carassius carassius tail infected with three gravid female P. sanguineus, showing nematodes within same inter-ray space (arrow) (scale bar = 10 mm). (e) Ruptured female P. sanguineus (arrow) trailing from the tail of C. carassius following larval dispersal (scale bar = 10 mm). (f) Scanning electron micrograph of female nematode (*) following larval dispersal. The tunnel (arrow) in which the nematode developed can be clearly seen (scale bar = 1 mm). (g) Raised nodule (arrow) in the dorsal region of juvenile C. carassius, caused by a single female nematode (scale bar = 1 mm). (h) Caudal swelling (arrow) resulting from penetration of a single P. sanguineus into the base of the tail (scale bar = 1 mm).

Gravid female P. sanguineus were first detected in the fins of crucian carp in early September and remained within this location until May. Nematodes detected throughout this period varied in size, colour and state of reproductive development. Two female P. sanguineus recovered from the caudal musculature of a single crucian carp in September were consistent with nematodes in mid-migration to the fins. These individuals measured approximately 5 mm in length and were not easily detected in the host tissues. Gravid female nematodes recently established within the fins measured between 12 and 14 mm, were a light, translucent brown in colour and were covered in numerous cuticular bosses. By October, infections of female P. sanguineus were very conspicuous (fig. 1b), consisting of bright red nematodes measuring between 38 and 51 mm in length. Female P. sanguineus retained this red colouration throughout winter and spring, ranging from 32 to 54 mm in April. Nematodes examined between September and May revealed clear larval development. The round eggs recorded in autumn became progressively elongated and active throughout the winter and early spring. By April and May all gravid female parasites examined contained highly active, fully developed larvae.

The tail was the primary site of female P. sanguineus infection (fig. 1b) with 90.1% of nematodes recorded within this position. Nematodes were less frequently observed within the dorsal fin (fig. 1c) (4.5%), pectoral fin (2.3%) and anal fin (2.3%). In the majority of fish examined, female nematodes were positioned in a U-shape, with the head and tail extending toward the fin tip and the parasites' mid-body into the fin base (fig. 1d). Female nematodes generally utilized different positions within the fins, although parasites crossing the fin ray elements (fig. 1c) or positioned within the same inter-ray space (fig. 1d) were also observed.

The process of larval dispersal was observed during May in three infected crucian carp. This involved emergence of nematodes from between the fin rays, until over half of the body was hanging free in the water. Female worms became noticeably turgid before bursting open, releasing a visible cloud of larvae into the water. Remnants of ruptured nematodes remained temporarily attached to the host (fig. 1e and f). The process of larval dispersal did not appear to be synchronized, with affected fish retaining gravid nematodes within the fins following emergence of others.

Gross pathological changes

Crucian carp measuring between 62 and 191 mm in length did not show any gross abnormalities or clinical signs as a consequence of P. sanguineus infection. An accumulation of opaque material within the fins, particularly around the head and tail of female parasites, was occasionally observed. In juvenile crucian carp measuring less than 60 mm in length, female nematodes extended deep into the fin bases, causing raised swellings of the dorsal (fig. 1g) and caudal (fig. 1h) tissues. This was accompanied by the displacement of scales within these regions. Despite these abnormalities, the skin surrounding these parasites remained intact until the onset of larval dispersal.

Histopathological changes caused by P. sanguineus to the fins of crucian carp

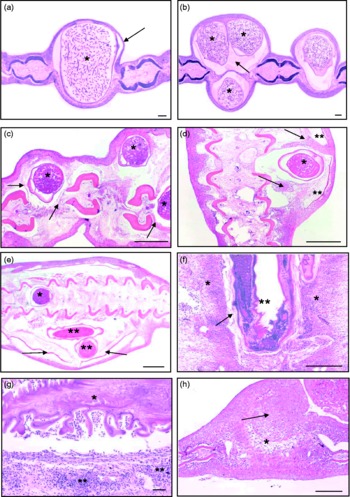

Infections of male and pre-copulated female P. sanguineus, located under the serosal surface of the swim-bladder, caused no changes of pathological importance. Gravid female nematodes within the fins of crucian carp caused localized distention and distortion of the fin tissue (fig. 2a) and displacement of fin ray elements, with compression and thinning of the epithelium. Distortion of the fins was accentuated when more than one parasite shared the same position within the fin (fig. 2b).

Fig. 2 (a) Transverse section (TS) of Carassius carassius tail with a single Philometroides sanguineus (*) causing localized distension of inter-ray space and thinning of epithelium (arrow) (scale bar = 100 μm). (b) Female nematodes (*) positioned between the same fin rays, accentuating swelling of the caudal fin. Eosinophylic material (arrow), containing macrophages, lymphocytes and exfoliated host cells, surrounds the parasite (scale bar = 100 μm). (c) TS of C. carassius dorsal fin infected with three gravid nematodes (*) causing displacement of fin rays, localized degeneration of skeletal muscle and compression of connective tissues (arrows) (scale bar = 1 mm). (d) Swelling of the caudal region of C. carassius. Presence of a single P. sanguineus (*) causing distortion of fin rays and displacement of scales (**). Hyperplastic epidermis (arrows) has partially surrounded the parasite (scale bar = 1 mm). (e) Pronounced swelling of the caudal region of C. carassius, with scale displacement (arrows). Nematodes can be seen between the fin ray elements (*) extending into the tissue under the skin (**) (scale bar = 1 mm). (f) Infiltration of inflammatory cells (*) surrounding a newly established nematode (**) in the tail. Connective tissue along the sides of the nematode (arrow) represents early encapsulation (scale bar = 1 mm). (g) Carassius carassius tail following larval dispersal. Collapse of the parasite (*), with shrinkage of the cuticle, is accompanied by an acute inflammatory response (**) directed toward the parasite (scale bar = 100 μm). (h) TS of caudal fin following parasite emergence. Hyperplasia of tissues between the fin rays can be seen (arrow), with connective tissue in the area vacated by the parasite (*) (scale bar = 1 mm).

In a number of infected fish, blood vessels within the fins were displaced by the presence of female nematodes, although no evidence of vessel damage or rupture was recorded. A homogeneous, eosinophilic layer containing macrophages, lymphocytes and exfoliated host cells was commonly observed between the cuticle of P. sanguineus and surrounding host tissue (fig. 2b). The cuticular bosses covering these nematodes were associated with the indentation of epithelium (fig. 2a) and may have been responsible for the observed cell displacement.

The severity of pathological changes caused by P. sanguineus was influenced strongly by host size, being most pronounced in smaller crucian carp. Infections in large fish (>150 mm) were accompanied by relatively localized pathological changes and only mild inflammatory changes. In contrast, the presence of gravid female P. sanguineus within the fins of juvenile crucian carp led to fin distortion, displacement of tissues along the fin bases, compression and localized degenerative changes (fig. 2c, d and e). In many cases, the muscle surrounding these nematodes was replaced by loose connective tissue interspersed with capillaries and inflammatory cells.

In very small crucian carp ( < 60 mm), female P. sanguineus appeared to extend further into the fin bases and caudal musculature, leading to more pronounced pathological changes than those localized between the fin rays. These infections consisted of nematodes between the fin-ray elements, but also extending into tissues under the skin. These infections caused scale displacement and marked swelling of the dorsal and caudal regions (fig. 2d and e). The epidermis within these regions was often hyperplastic, partly surrounding the nematodes beneath (fig. 2d). These observations were also accompanied by an influx of inflammatory cells within the epidermis.

Inflammatory changes caused by P. sanguineus infection were associated mainly with the seasonal migrations of nematodes into and out of the fins. Parasites recently established in the fins (identified by time of year, nematode size and larval development) provoked an acute inflammatory response comprising large numbers of eosinophils and neutrophils. This reaction was particularly concentrated at the periphery of each nematode (fig. 2f), and was accompanied by localized oedema, hyperplasia, congestion and compression. More established infections (observed in February) revealed the accumulation of host cells around each nematode forming a tunnel of connective tissue. This appeared to partially encapsulate the nematode within a membrane of host tissue. Between the periods of establishment within the fins and larval dispersal, female nematodes remained relatively dormant within the host tissues, causing little additional damage. This was particularly evident in large fish, where infections throughout the winter period appeared benign.

The emergence of gravid female parasites in spring for the purpose of larval dispersal caused additional mechanical damage to the fins and breached the integrity of the skin. This reproductive behaviour was associated with an influx of inflammatory cells around the parasite consisting of granular cells, eosinophils, neutrophils and aggregations of lymphoid cells. This represented a pronounced immune response to infection. The rupture of nematodes during larval dispersal resulted in rapid shrinkage of the parasite and collapse of the cuticle within the fin (fig. 2g). In such cases, large numbers of inflammatory cells and small numbers of blood cells were observed adjacent to the parasite's cuticle (fig. 2g). During multiple parasite infections inflammation extended beyond the direct site of parasite attachment, with increased numbers of inflammatory cells extending throughout the fin. Examination of fin tissue after parasite emergence revealed hyperplasia of the epidermis, localized necrotic changes and a central mass of connective tissue in the area vacated by the parasite (fig. 2h).

Discussion

The literature suggests that philometrid nematodes can have profound detrimental effects on fish (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Musselius and Strelkov Yu1969; Paperna & Zwerner, Reference Paperna and Zwerner1976; Moravec & Dykova, Reference Moravec and Dykova1978; Sinderman, Reference Sinderman1987; Moravec, Reference Moravec1994, Reference Moravec2004a, Reference Moravec2006; Kaall et al., Reference Kaall, Sarvala and Fagerholm2001; Wang, Reference Wang2002; Moravec et al., Reference Moravec, Glamuzina, Marino, Merella and Di Cave2003). In particular, parasites of the genus Philometroides have been associated with disease in a range of freshwater fish species. Examples include P. cyprini (syn. P. lusiana, P. lusii) within the skin of common carp (Vismanis, Reference Vismanis1966; Vasilkov, Reference Vasilkov1967, Reference Vasilkov1983; Schäperclaus et al., Reference Schäperclaus, Kulow and Schreckenbach1991; Moravec, Reference Moravec2004a; Moravec & Cervinka, Reference Moravec and Cervinka2005), P. sanguineus within the fins of crucian carp (Wierzbicki, Reference Wierzbicki1958, Reference Wierzbicki1960; Vismanis & Nikulina, Reference Vismanis and Nikulina1968; Vismanis, Reference Vismanis1978; Vasilkov, Reference Vasilkov1983; Moravec, Reference Moravec1994), P. fulvidraco Yu, Wu & Wang, 1993 in the eyes of bullhead catfish (Wang, Reference Wang2002) and P. huronensis Uhazy, 1976 within the skin of freshwater suckers (Uhazy, Reference Uhazy1978; Vasilkov, Reference Vasilkov1983; Moravec, Reference Moravec1994). Despite these accounts, little detailed information exists on the epidemiology and pathological lesions caused by these parasites. According to Williams (Reference Williams1967) and more recently Moravec (Reference Moravec1994) and Molnar et al. (Reference Molnar, Buchmann, Szekely and Woo2006), the pathogenicity of parasitic nematodes is one of the most neglected fields of fisheries parasitology. This paper provides the first account of the pathological changes associated with P. sanguineus in wild crucian carp.

The damage caused by P. sanguineus was influenced strongly by host size and the seasonal migrations of nematodes into and out of the fins. Adult crucian carp harbouring up to eight female parasites showed no obvious signs of debilitation, with relatively localized tissue damage and mild inflammatory responses. In contrast, infections of P. sanguineus in smaller fish were characterized by swelling of the fin bases, fin distortion, tissue displacement, degenerative changes and marked inflammatory responses during periods of nematode activity. The severity of these changes was attributed to the fact that in very small fish, nematodes extended further into the fin bases, leading to greater tissue damage and a larger proportion of host tissue being displaced by these parasites.

Margolis (Reference Margolis and Snieszko1970) highlighted the importance of host and parasite size in the pathogenicity of nematodes, suggesting there may be a cut-off size under which fish become noticeably diseased, and over which hosts tolerate infection. According to Wierzbicki (Reference Wierzbicki1958, Reference Wierzbicki1960) who conducted experimental studies to elucidate the life-cycle development of P. sanguineus, crucian carp measuring less than 90 mm do not survive infection. Unfortunately, no information was provided on parasite intensity or clinical signs of disease. Current histopathological observations of crucian carp measuring 90 mm and harbouring up to five female nematodes revealed a number of pathological changes. However, these were mainly localized and were considered unlikely to cause serious host debilitation. In the samples examined, crucian carp measuring less than 60 mm appeared to be most compromised by P. sanguineus infection, indicating that impacts in wild fish populations may be limited to only very small fish. Recent studies on the growth and reproduction of crucian carp in England indicate that this size corresponds to fish within their first year of life (Tarkan et al., Reference Tarkan, Copp, Zieba, Godard and Cucherousset2009).

Within Eastern Europe, crucian carp may attain only 20 mm in their first year and gain maturity at less than 60 mm (Szczerbowski et al., Reference Szczerbowski, Zakes, Luczynski and Szkudlarek1997). In the UK, farmed 0+crucian carp may exceed 100 mm (Henshaw, pers. comm.), although a wild fish reaching 60 mm in its first year is quite exceptional (Tarkan et al., Reference Tarkan, Copp, Zieba, Godard and Cucherousset2009). This elasticity in host size is likely to be an important factor dictating the degree of impact of P. sanguineus in crucian carp populations. Factors affecting crucian carp growth, including population density, food availability, pond succession status and seasonal temperatures (Laurila et al., Reference Laurila, Piironen and Holopainen1987; Copp et al., Reference Copp, Warrington and Wesley2008; Tarkan et al., Reference Tarkan, Copp, Zieba, Godard and Cucherousset2009) may therefore determine susceptibility to P. sanguineus infection. This highlights the importance of considering host age, as well as host size when detailing the pathological changes associated with fish parasites, particularly those that may have a seasonal influence on fish (Chubb, Reference Chubb1980).

In England, P. sanguineus follows a seasonal cycle of development and reproduction. Parasite infections in crucian carp are acquired during spring, followed by the migration of female nematodes into the fins during summer, reproductive development throughout winter and larval dispersal the following spring. This is consistent with published literature on the development of P. sanguineus in other parts of Europe (Yashchuk, Reference Yashchuk1971; Vismanis, Reference Vismanis1978; Chubb, Reference Chubb1980). The absence of sampling during early summer prevented observations of P. sanguineus transmission in crucian carp following the ingestion of infected copepods. It is well recognized that the penetration of larval nematodes through the intestine of infected fish can be the cause of tissue damage. However, the very small size of these parasites and low numbers of adult P. sanguineus recorded within host tissues suggest that this is less important than migrations of post-copulated female parasites. Similarly, the encapsulation of female nematodes within the fins throughout winter limited host damage when compared with female parasites in their migratory phases. This is consistent with other parasitic nematodes (Choudhury & Cole, Reference Choudhury, Cole, Eiras, Segner, Wahli and Kapoor2008), including P. huronensis in the skin of the white sucker, Catostomus commersonii (see Uhazy, Reference Uhazy1978).

The process of larval dispersal, also known as ‘functional bursting’ (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Jones and Adams1974), is characteristic of many philometrid nematodes and can be potentially harmful to infected fish (Moravec & Dykova, Reference Moravec and Dykova1978; Uhazy, Reference Uhazy1978; Vasilkov, Reference Vasilkov1983; Moravec, Reference Moravec1994; Wang, Reference Wang2002). During the present study, this reproductive behaviour was accompanied by pronounced inflammatory changes and loss of skin integrity. Such damage may increase susceptibility of infected fish to secondary infections (Schäperclaus et al., Reference Schäperclaus, Kulow and Schreckenbach1991). These observations confirm that the seasonal activity of P. sanguineus holds important implications for infected fish, with autumn and spring being the most susceptible periods for small crucian carp.

According to Vasilkov (Reference Vasilkov1983), philometroidosis was responsible for serious losses in crucian carp fry in the Ukraine, where prevalence of infection reached 100% of the population. The disease occurred either in an acute form, which resulted from newly acquired infections in 6- to 8-week-old fry, or as a chronic infection, which debilitated infected hosts during migration and development of adult female parasites. Vismanis & Nikulina (Reference Vismanis and Nikulina1968) reported a mass mortality of small crucian carp in Russia in 1966 as a result of heavy parasitic infections. Infections in wild fish populations have also been recorded in Czechoslovakia (Cakay, Reference Cakay1957), Poland (Wierzbicki, Reference Wierzbicki1960) and Hungary (Molnar, Reference Molnar1966). These impacts are supported by experimental observations, which indicate that small crucian carp are unable to withstand internal migrations of P. sanguineus (Wierzbicki, Reference Wierzbicki1958, Reference Wierzbicki1960). According to Vasilkov (Reference Vasilkov1967), infections of just three P. cyprini are known to kill common carp fry, with up to 50% mortality, adding support to the idea that 0+fish are very vulnerable to the consequences of infection. Histopathological observations of P. sanguineus support the potential for disease in crucian carp fry. However, the low prevalence and intensity of infections recorded in sites throughout England suggests that this may affect only a small proportion of fish and questions the importance of these infections at the population level.

During the current study, the smallest infected fish examined measured 54 mm and harboured a single female nematode. Scale reading confirmed that this fish was 1+years old. To date, no infected 0+crucian carp have been recorded in England and Wales, despite the examination of many small fish from infected fisheries. This could be a consequence of parasite-induced mortality, supported by records of acute philometroidosis outbreaks during spring in fry populations (Vasilkov, Reference Vasilkov1967). If this possibility is true, then infections in 0+fish may have been missed by the spot-sampling conducted in this study. However, it is considered more likely that this absence is the result of mis-timing between the presence of infected copepods during early summer and the ingestion of this intermediate host by crucian carp fry. Yaschuk (Reference Yashchuk1974) highlighted the narrow window of transmission of P. sanguineus in early summer, suggesting this could be used to control disease risks when stocking farm ponds. Golléty et al. (Reference Gollety, Connors, Adams, Roumillat and Buron2005) recorded an absence of the philometrid nematode, Margolisianum bulbosum, in the small southern flounder, Paralichthys lethostigma. This was attributed to delayed development of larvae within this host, rather than an absence of infection. Current observations suggest that 0+crucian carp either lack infection, or that prevalence in these hosts is so low that sampling has so far limited observations of these individuals. Consequently, the lesions associated with P. sanguineus in 1+crucian carp may represent a gross underestimate of pathogenicity in 0+fish, should these fish become infected. Further studies are required to assess the susceptibility of fry to P. sanguineus infection and the factors dictating transmission within this year class (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000).

Nematodes are often considered to be benign parasites and seldom the cause of mortality (Sinderman, Reference Sinderman1987). Notwithstanding, sub-lethal infections can have important implications for wild fish populations (Sinderman, Reference Sinderman1987; Choudhury & Cole, Reference Choudhury, Cole, Eiras, Segner, Wahli and Kapoor2008). Philometra saltatrix infects the gonads of sexually mature Atlantic bluefish Pomatomas saltatrix. These infections cause no gross disease signs, but reduce reproductive potential (Sinderman, Reference Sinderman1987). This nematode has also been described as a serious pathogen of 0+bluefish, causing necrosis and inflammation of the heart and pericardial cavity (Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Nigrelli and Ruggieri1984). According to Genc et al. (Reference Genc, Ayce Genc, Genc, Cengizler and Faith Can2005) Philometra lateolabracis causes severe lesions in the ovaries of groupers, disturbing egg release and blocking ovarian ducts. Heavy infections of P. fulvidraconi are known to cause lens opacity, eye loss and occasional mortality of bullhead catfish Pseudobagrus fulvidraconi in China (Yu et al., Reference Yu, Wang, Feng, Wu and Wang1993). Infections of Philometra ovata caused abdominal swelling and impaired the swimming ability of wild-caught Gobio lozanoi from Portugal (Saraiva et al., Reference Saraiva, Hermida, Costa, Maia, Reis, Cruz and Valente2008). The close association of P. sanguineus with the fins of crucian carp could have similar effects, reducing fin movement, swimming performance or even the ability to escape predators. Similar effects have been proposed for Philometroides paralichthydis in marine flatfish (de Buron & Roumillat, Reference de Buron and Roumillat2010). In the case of P. sanguineus, it is understandable how the migration and development of a nematode that exceeds the length of its host, and is maintained throughout the first year of a fish's life, could cause debilitation. However, identifying and evaluating such effects in wild fish populations remains problematic, as sick fish are rapidly removed by predators, water flow and necrophages (Blanc, Reference Blanc1997).

According to Schäperclaus et al. (Reference Schäperclaus, Kulow and Schreckenbach1991) fish infected with Philometroides spp. should, under no circumstances, be used for stocking fisheries. Following the importation of P. cyprini to the Czech Republic, a consignment of infected common carp was destroyed and facilities disinfected based upon potential disease threats (Moravec & Cervinka, Reference Moravec and Cervinka2005). Crucian carp infected with P. sanguineus have been restricted from movement in England and Wales, based on the precautionary approach to non-native parasite introductions and fishery management (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy, Pike and Lewis1994; Hickley, Reference Hickley2009). Precaution is an important consideration in the management of crucian carp populations (Copp et al., Reference Copp, Warrington and Wesley2008). However, this cannot alone be used to justify long-term decision-making, requiring observational data to evaluate disease risks.

Current studies provide little evidence to suggest that P. sanguineus is a serious pathogen of adult crucian carp at the intensities recorded. The absence of severe tissue damage or gross pathological changes in most of the fish examined indicates tolerance to these infections. This observation may be explained by three possibilities. First, P. sanguineus is not as pathogenic as the literature suggests. Second, environmental stressors play an important role in the characterization of disease. In such cases, only heavy infections may be damaging, while light infections lead to minor physiological disturbance or sub-clinical debilitation. This is known to occur with nematode burdens in both fish and terrestrial animals (Crichton & Beverley-Burton, Reference Crichton and Beverley-Burton1977; Sekretaryuk, Reference Sekretaryuk1980, Reference Sekretaryuk1983; Gulland, Reference Gulland1992). The third possibility is that the parasite is pathogenic only to very small fish (Wierzbicki, Reference Wierzbicki1958; Vasilkov, Reference Vasilkov1983; Moravec, Reference Moravec1994), being tolerated once crucian carp attain a certain size. Histopathological observations support this assumption. Further studies are under way to assess the susceptibility of crucian carp fry to P. sanguineus infection and the importance of this nematode in the recruitment of wild crucian carp populations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Environment Agency staff for help with obtaining fish samples. Particular thanks to Amy Reading and Jody Armitage, Environment Agency for help with parasitological examinations. Thanks also go to Kelly Bateman (Cefas, Weymouth) for assistance with scanning electron microscopy. The opinions provided in this paper are those of the authors and not their parent organizations.