Introduction

Lung flukes of the genus Paragonimus Braun, 1899 are trematodes that parasitize the lungs of animals and humans causing paragonimiasis. It is a typical food-borne parasitic zoonosis which occurs worldwide, particularly in Asia, Africa and the Americas (Blair et al., Reference Blair, Xu and Agatsuma1999). To date, more than 50 species have been reported (Blair et al., Reference Blair, Xu and Agatsuma1999; Nawa et al., Reference Nawa, Thaenkham, Doanh, Blair and Motarjemi2014; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Doanh, Nawa, Xiao, Ryan and Feng2015). The most common natural definitive hosts for Paragonimus species are a wide range of carnivorous/omnivorous wild mammals including tigers, lions, leopards, panthers, foxes, wolves, wild cats, mongooses, civets, macaques and wild boars. Domestic animals including dogs, cats and pigs are also naturally infected with Paragonimus species, although they are usually reported as experimental definitive hosts. Humans can become infected with several Paragonimus species, such as P. westermani, P. heterotremus, P. skrjabini, P. africanus, P. kellicotti, P. uterobilateralis and P. mexicanus (Blair et al., Reference Blair, Xu and Agatsuma1999, Reference Blair, Agatsuma, Wang, Murrell and Fried2007; Nawa et al., Reference Nawa, Thaenkham, Doanh, Blair and Motarjemi2014; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Doanh, Nawa, Xiao, Ryan and Feng2015). The definitive hosts become infected by eating raw or under-cooked second intermediate hosts such as crustaceans, crabs or crayfishes, which contain live metacercariae, or by eating under-cooked meat of paratenic hosts containing juvenile worms (Blair et al., Reference Blair, Xu and Agatsuma1999; Nawa et al., Reference Nawa, Thaenkham, Doanh, Blair and Motarjemi2014; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Doanh, Nawa, Xiao, Ryan and Feng2015).

In Vietnam, Paragonimus and paragonimiasis have been studied in the northern and central provinces, and seven species, P. heterotremus, P. vietnamensis, P. bangkokensis, P. proliferus, P. westermani, P. harinasutai and P. skrjabini, have been reported so far (Kino et al., Reference Kino, De, Vien, Chuyen and Sano1995; Doanh et al., Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Habe, Nawa, The and Le2007a, Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Habe, Nawa and Leb, Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Habe, Nawa and Le2008, Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Habe and Nawa2009a, Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Yahiro, Habe, Vannavong, Strobel, Nakamura and Nawab, Reference Doanh, Hien, Nonaka, Horii and Nawa2012, Reference Doanh, Hien, Nonaka, Horii and Nawa2013a, Reference Doanh, Horii and Nawab). Of these, the natural definitive hosts for P. heterotremus in northern Vietnam were confirmed as dogs, civets and humans (Kino et al., Reference Kino, De, Vien, Chuyen and Sano1995; Vien et al., Reference Vien1997; De et al., Reference De, Murrell, Cong, Cam, Chau and Toan2003; Le et al., Reference Le, De, Blair, McManus, Kino and Agatsuma2006; Doanh et al., Reference Doanh, Thach, Dung, Shinohara, Horii and Nawa2011). However, the natural definitive hosts for the other six species have not yet been identified (Doanh et al., Reference Doanh, Horii and Nawa2013b). This is mainly due to the difficulties associated with sampling wild animals. Adult worms of these species were obtained from experimentally infected dogs or cats fed with metacercariae collected from second intermediate crab hosts in Vietnam (Doanh et al., Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Habe, Nawa, The and Le2007a, Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Habe, Nawa and Leb, Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Habe, Nawa and Le2008, Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Habe and Nawa2009a, Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Yahiro, Habe, Vannavong, Strobel, Nakamura and Nawab, Reference Doanh, Hien, Nonaka, Horii and Nawa2012). Recently we found an extremely high prevalence of metacercariae of P. westermani in particular, but also P. proliferus, P. bangkokensis and P. harinasutai, in second intermediate crab hosts in Quang Tri province, central Vietnam (Doanh et al., Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Habe and Nawa2009a, Reference Doanh, Hien, Nonaka, Horii and Nawa2012, Reference Doanh, Hien, Nonaka, Horii and Nawa2013a). Because wild carnivorous/omnivorous animals are the common definitive hosts for Paragonimus species (Blair et al., Reference Blair, Xu and Agatsuma2009), we hypothesized that wild mammals in Quang Tri province, central Vietnam are highly infected with Paragonimus spp., especially with P. westermani. Paragonimus westermani is an important pathogen in human paragonimiasis and therefore elucidating the life cycle of this parasite is important for designing preventive measures.

Traditionally the identification of Paragonimus species and their definitive hosts was based on the morphological features of adult worms isolated from the lungs of mammalian hosts. However, this approach is not always possible, especially in cases where wild animals are located in a sanctuary. The morphology of Paragonimus eggs can be used for identification of the genus but not for determining the species. Recently, the nuclear ribosomal second internal transcribed spacer region (ITS2) has become a useful marker for identification of Paragonimus eggs isolated from human sputum and faeces (Chang et al., Reference Chan, Wu, Blair, Zhang, Hu, Chen, Chen, Feng and George2000; Le et al., Reference Le, De, Blair, McManus, Kino and Agatsuma2006; Odermatt et al., Reference Odermatt, Habe, Maichanh, Tran, Duong and Zhang2007; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Sugiyama, Umehara, Hiese and Khalo2009; Doanh et al., Reference Doanh, Thach, Dung, Shinohara, Horii and Nawa2011). Because mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is well preserved in degraded tissues and easy to process for molecular analysis, mitochondrial cytochrome b (Cyt b), cytochrome oxidase I (COI) and D-loop regions have all been used as genetic markers to identify mammals (Randi, Reference Randi and Baker2000). Of these, the D-loop region is most widely used (Fajardo et al., Reference Fajardo, González, López-Calleja, Martín, Rojas, Hernández and Martin2007; Nonaka et al., Reference Nonaka, Sano, Inoue, Armua, Fukui, Katakura and Oku2009; Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Singh, Umapathi, Nagappa and Gaurav2011; Parkanyi et al., Reference Parkanyi, Ondruska, Vasicek and Slamecka2014). In this study, we examined faecal samples from wild animals in Quang Tri province, central Vietnam, and used ITS2 to identify Paragonimus eggs isolated from the samples, and the D-loop region to identify the definitive host.

Materials and methods

Collection and examination of faecal samples

Faecal samples from wild animals were collected in Da Krong Nature Reserve, Da Krong district, Quang Tri province in May 2014, where Paragonimus metacercariae are highly prevalent in the second intermediate crab hosts (Doanh et al., Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Habe and Nawa2009a, Reference Doanh, Hien, Nonaka, Horii and Nawa2012). Faecal samples were stored at − 20°c in falcon tubes containing 100% ethanol until use.

Faecal samples (approximately 4 g) were divided into two, and one-half was used for the detection of trematode eggs using a sedimentation technique. Two grams of faeces were dissolved in 300 ml of tap water and passed through a wire mesh (pore size: 150 μm). After 3–5 rounds of sedimentation/decantation, the sediment was transferred to a Petri dish and checked for trematode eggs under a stereomicroscope. Paragonimus eggs, which are normally 75–90 × 40–45 μm in size with an operculum at the larger end, and other trematode eggs were picked up and fixed separately in 100% ethanol. The eggs were used for species identification by molecular analysis.

Molecular analysis

Fixed eggs were washed with distilled water and 15 from each faecal sample were transferred to a 200-μl polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tube containing 8 μl of proteinase K digestion solution (10 mm Tris–HCl; 50 mm KCl; 2.5 mm MgCl2; 0.45% Tween-20; 500 μg/ml proteinase K). The eggs were mechanically crushed using a syringe needle under a stereomicroscope and genomic DNA was extracted by incubation at 60°C for 60 min followed by 90°C for 15 min to inactivate the proteinase K. This DNA solution was used for PCR amplification of ITS2 without any further purification. For this purpose, 42 μl of HotStarTaq Master Mix (Qiagen, Valencia, California, USA) and primer pairs 3S (forward, 5′-CGC TGG ATC ACT CGG CTC GT-3′) and A28 (reverse, 5′-CCT GGT TAG TTT CTT TTC CTC CGC-3′) (Bowles et al., Reference Bowles, Blair and McManus1995) were added to the DNA solution to a final volume of 50 μl. PCR conditions were as described previously (Doanh et al., Reference Doanh, Thach, Dung, Shinohara, Horii and Nawa2011). The PCR products were purified using a QIAquick PCR purification Kit (Qiagen) and primed using a Big-Dye terminator cycle sequencing kit v3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, California, USA). Both forward and reverse strands were sequenced directly using a Genetic Analyzer (Model 3100, Applied Biosystems). The ITS2 sequences obtained from the eggs were analysed for species identification by homology searches using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) in the GenBank server of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and aligned with the reference sequences using MEGA 6.0 software (Tamura et al., Reference Tamura, Stecher, Peterson, Filipski and Kumar2013).

The remaining half of the Paragonimus egg-positive faecal sample was used to identify the host species by molecular techniques described by Nonaka et al. (Reference Nonaka, Sano, Inoue, Armua, Fukui, Katakura and Oku2009). Total DNA was extracted from faecal samples using a QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen). The D-loop region of the mitochondrial genome was amplified with primer pairs, prL (5′-CACCATTAGCACCCAAAGCT-3′) and prH (5′-CCTGAAGTAGGAACCAGATG-3′), which were designed to amplify part of the D-loop region of carnivores, using the PCR procedure described previously (Nonaka et al., Reference Nonaka, Sano, Inoue, Armua, Fukui, Katakura and Oku2009). PCR products were purified using a Qiaquick PCR purification Kit (Qiagen), then primed using a Big-Dye terminator cycle sequencing kit v3.1 (Applied Biosystems). Both forward and reverse strands were sequenced directly using a Genetic Analyzer 3100 (Applied Biosystems). The nucleotide sequence of each sample was identified using BLAST searches for high homology sequences from GenBank and aligned with the reference sequence using MEGA 6.0 software (Tamura et al., Reference Tamura, Stecher, Peterson, Filipski and Kumar2013).

Results and discussion

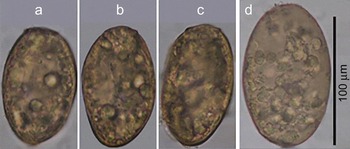

Paragonimus eggs (fig. 1a–c) were detected in 7 of the 120 faecal samples collected from wild animals in Da Krong Nature Reserve, Da Krong district, Quang Tri province, Vietnam. All ITS2 sequences were single wave patterns and were submitted to GenBank (accession numbers LC025641–LC025647). The results of BLAST searches showed that they were completely or almost completely identical (99–100%) to the ITS2 sequences of P. westermani (3 samples), P. skrjabini (2 samples) and P. heterotremus (2 samples). The P. skrjabini sequences were identical to each other, while only one nucleotide variation was found among P. westermani and between P. heterotremus sequences. They also showed high similarities to the reference sequences (100% for P. skrjabini AB703444; 99.8–100% for P. heterotremus AB827365 and 99.3–99.6% for P. westermani JN656208).

Fig. 1 Eggs of Paragonimus spp. (a–c) and Pharyngostomum cordatum (d) collected from faecal samples of wild cats in Quang Tri province, Vietnam.

Other trematode eggs which were larger than Paragonimus eggs (105–110 × 65–70 μm, fig. 1d), were occasionally found in the same or in other faecal samples. The ITS2 sequence of these eggs was submitted to GenBank (accession number LC025648). The BLAST search and alignment results showed that this sequence was highly similar (99%) to that of Pharyngostomum cordatum (reference sequence KJ137230), which is a typical intestinal trematode of domestic and wild cats (Wallace, Reference Wallace1939; Chai et al., Reference Chai, Sohn, Chung, Hong and Lee1990).

The D-loop sequences from seven Paragonimus egg-positive faecal samples were obtained and submitted to GenBank (accession numbers LC025634–LC025640). All of the sequences showed high similarities (98%) to that of the wild cat, Prionailurus bengalensis (reference sequence AB210259). After alignment, nucleotide variations were seen at only 1–2 positions in the partial D-loop sequences.

In this study, molecular techniques were applied successfully to identify Paragonimus species and their definitive host species from faecal samples of wild animals. The wild cat, P. bengalensis, was identified as the natural definitive host for three species, P. westermani, P. skrjabini and P. heterotremus, in Da Krong district, Quang Tri province, central Vietnam. Metacercariae of P. westermani have been reported to be highly prevalent in crab hosts (Doanh et al., Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Habe and Nawa2009a, Reference Doanh, Hien, Nonaka, Horii and Nawa2012), but those of P. skrjabini and P. heterotremus have not been detected previously in crab hosts in Quang Tri province (Doanh et al., Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Habe and Nawa2009a, Reference Doanh, Hien, Nonaka, Horii and Nawa2012, Reference Doanh, Hien, Nonaka, Horii and Nawa2013a). This may be due to a low prevalence or to difficulties in differentiation of metacercariae, especially between P. westermani and P. skrjabini, because of their morphological similarities (Miyazaki, Reference Miyazaki1991; Doanh et al. Reference Doanh, Horii and Nawa2013b). We propose that P. skrjabini and P. heterotremus metacercariae in crab hosts should be investigated during epidemiological surveys for Paragonimus in this area.

We identified another type of trematode egg in addition to Paragonimus eggs in the faecal samples. With the same procedure and primer pair, we also successfully obtained the ITS2 sequence of these eggs. They were molecularly identified as P. cordatum. Paragonimus and Pharyngostomum species exploit basically different second intermediate hosts, crabs for the former and tadpoles/frogs for the latter (Wallace, Reference Wallace1939; Chai et al., Reference Chai, Sohn, Chung, Hong and Lee1990; Blair et al., Reference Blair, Xu and Agatsuma1999). However, frogs have been reported as a paratenic host for Paragonimus species, at least for P. skrjabini (Xie et al., Reference Xie, Yang, Li and Tang1985). Thus, the definitive host can potentially become co-infected with both trematode species by ingesting co-infected frogs. Alternatively, if the definitive mammalian host consumed both crabs and frogs, or any small animals that can serve as the paratenic hosts, they can become co-infected with Paragonimus and Pharyngostomum species simultaneously. Paratenic hosts were confirmed to be involved in the life cycles of all of these fluke species (Wallace, Reference Wallace1939; Chai et al., Reference Chai, Sohn, Chung, Hong and Lee1990; Blair et al., Reference Blair, Xu and Agatsuma1999). Because wild cats are the most common hosts for P. cordatum (Wallace, Reference Wallace1939; Chai et al., Reference Chai, Sohn, Chung, Hong and Lee1990), detection of P. cordatum eggs in faecal samples that are also positive for Paragonimus species provides supporting evidence that the Paragonimus egg-positive faecal samples are from wild cats, and that this animal serves as the natural definitive host for Paragonimus species in this study area.

In the Da Krong Nature Reserve, Quang Tri province, 24 carnivorous mammals were recorded previously (Tin & Huynh, Reference Tin and Huynh1994), but Manh et al. (Reference Manh, Dang and Nghia2009) observed only two species, the wild cat, P. bengalensis, and the small Asian mongoose, Herpestes javanicus, during their recent long-term (100 days) observation of this sanctuary. Although small Asian mongooses, Herpestes spp., are considered to be the potential definitive hosts for Paragonimus species (Blair et al., Reference Blair, Xu and Agatsuma1999), we identified only wild cats as the mammalian host for Paragonimus species in our study. Despite the high prevalence of P. westermani metacercariae in crab hosts in central Vietnam, human paragonimiasis cases have not yet been recognized (Doanh et al., Reference Doanh, Shinohara, Horii, Habe and Nawa2009a, Reference Doanh, Thach, Dung, Shinohara, Horii and Nawa2011). The number of infected animals in this study was far lower than that expected based on the prevalence of the parasite in crab hosts. This suggests that other mammals, including humans, in addition to wild cats, may be involved in maintaining the life cycle of Paragonimus species in central Vietnam.

In conclusion, wild cats, P. bengalensis, were identified as the natural hosts for three Paragonimus species, P. westermani, P. skrjabini and P. heterotremus, in Quang Tri province, central Vietnam. Paragonimiasis should be considered in disease surveillance of wildlife, domestic mammals and residents in central Vietnam.

Financial support

This research was funded by the Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED) under grant number 106.12-2012.52.

Conflict of interest

None.