Introduction

There is much evidence for density-dependent regulation of gastrointestinal helminth populations (Keymer, Reference Keymer1982; Shostak & Scott, Reference Shostak and Scott1993). In acanthocephalan infrapopulations, the establishment and survival of individual worms (Uznanski & Nickol, Reference Uznanski and Nickol1982; Brown, Reference Brown1986; Poulin, Reference Poulin2006), their growth or their mean body length (Dezfuli et al., Reference Dezfuli, Volponi, Beltrami and Poulin2002; Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Giari, Simoni and Dezfuli2003; Hassanine & Al-Jahdali, Reference Hassanine and Al-Jahdali2008), their spatial distribution within the host gut (Lawlor et al., Reference Lawlor, Read, Keymer, Parveen and Crompton1990; Sinisalo et al., Reference Sinisalo, Poulin, Högmander, Juuti and Valtonen2004; Hassanine & Al-Jahdali, Reference Hassanine and Al-Jahdali2008) and the female–male ratio (Poulin, Reference Poulin1997a; Dezfuli et al., Reference Dezfuli, Volponi, Beltrami and Poulin2002; Hassanine & Al-Jahdali, Reference Hassanine and Al-Jahdali2008) are apparently the results of density-dependent processes, which through some form of intra- or interspecific competition, play an important role in shaping and regulating the infrapopulations. The mechanisms responsible for these processes have often been observed in laboratory studies but rarely studied under natural conditions. Very few studies (e.g. Dezfuli et al., Reference Dezfuli, Volponi, Beltrami and Poulin2002; Hassanine & Al-Jahdali, Reference Hassanine and Al-Jahdali2007, Reference Hassanine and Al-Jahdali2008) have examined intra- and interspecific effects on helminth growth in a natural context.

The siganid fish Siganus rivulatus Forsskål is common in the Red Sea and is parasitized by the cavisomid acanthocephalan Sclerocollum saudii Al-Jahdali, Reference Al-Jahdali2010 (see Al-Jahdali, Reference Al-Jahdali2010). In the present study, a considerable number of this acanthocephalan's infrapopulations were observed and analysed for the first time in the light of the above-mentioned information to explore some of the essential intrinsic factors acting on them under natural conditions.

Materials and methods

Collection and examination of fish for parasites

During June of 2009, a total of 30 specimens of the fish S. rivulatus Forsskål (Teleostei, Siganidae), ranging between 15 and 24 cm in total length, were examined for infections by acanthocephalans.

The fish were caught by hand net (by scuba-diving) in the Red Sea off the coast of Rabigh, Saudi Arabia, and identified according to Randall (1983); the names follow Froese & Pauly (2004/Reference Froese and Pauly2009). To avoid parasite post-mortem or other migration along the gastrointestinal tract, the fish were killed immediately after capture by a blow to the head and examined in a field laboratory (within 30–45 min after capture). Then the entire alimentary canal of each fish was immediately removed and, to record the exact position of individual parasites, the intestine was cut into ten equal sections, to reduce the cutting of more worms. Each section was opened and its contents examined under a dissecting stereomicroscope; all the worms found were examined alive while attached to intestinal mucosa, carefully teased out, re-examined alive in a saline solution and the opened section was then shaken vigorously in a jar of saline to dislodge further worms and to remove mucus. Acanthocephalans were relaxed in cold tap-water, fixed in 4% formaldehyde and stored in 70% ethanol for subsequent species identification. The infrapopulation collected from each individual fish host was carefully counted, and its position and distribution in the intestine were recorded. All acanthocephalans recovered were identified, sexed and measured (trunk length, in millimetres) using a stereomicroscope with an eyepiece micrometer. The different stages of the parasite were classified according to Al-Jahdali (Reference Al-Jahdali2010). Male worms were categorized as immature if the testes and other sexual organs were little developed, the seminal vesicle was hardly seen and the cement gland apparatus appeared to be shrivelled (not yet functional), and as mature if the testes and other sexual organs were fully developed and the seminal vesicle and cement glands were enlarged. Female worms were categorized as immature if the pseudocoel contained a ‘floating ovary’ or ovarian balls, as mature if the pseudocoel contained developed or fully developed eggs, as recently copulated if they had cement plugs remaining attached to their posterior ends, as copulated if the pseudocoel contained embryonated eggs, and as fully gravid if the pseudocoel was fully filled with embryonated eggs. Some acanthocephalans were fixed in hot 10% formalin under slight coverslip pressure, stored in 75% ethanol, stained in acid carmine, cleared in terpineol and mounted in Canada balsam.

Data analysis

The term ‘mean intensity’ follows the definition of Bush et al. (Reference Bush, Lafferty, Lotz and Shostak1997) and refers to the mean number of worms found per infected host. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (r s) was calculated to determine possible correlations between numbers of immature and mature females and their mean lengths, mean lengths of immature and mature females, numbers of immature and mature males and their mean lengths, mean lengths of immature and mature males, mean lengths of immature females and males, mean lengths of mature females and males, female–male ratio of immature and mature worms and infrapopulation size, and between female–male ratio and numbers of copulated females through all infrapopulations.

Results

Infection levels and worm distribution within the intestine

Of the 30 S. rivulatus examined, 24 (80%) were slightly or heavily parasitized by the developing and mature stages of the acanthocephalan S. saudii Al-Jahdali, Reference Al-Jahdali2010 (Cavisomidae); absence of other helminth parasites in the intestine of this fish excluded the confounding influence of interspecific interaction. A relatively large number of S. saudii (6274 specimens) belonging to 24 infrapopulations, ranging from 77 to 447 individuals, were collected from the infected fishes, with a mean intensity of 261.41 (SD ± 123.46) worms/host. There was no significant correlation between fish size and size of S. saudii infrapopulation (r s = 0.238478, P = 0.2502). Except for some dead immature females (see below), all the other worms were found alive. Living worms were firmly attached to the intestinal mucosa, their internal organs were easily seen through the body wall which was nearly transparent, their internal fluids exhibited some movement and their bodies slowly contracted and relaxed. Dead worms were loosely attached to the intestinal mucosa, their internal organs were hardly seen through the body wall which lost its transparency, their internal fluids exhibited no movement and their bodies were completely immobile. Infrapopulations were arranged according to their densities and the corresponding entire data set is shown in tables 1–3.

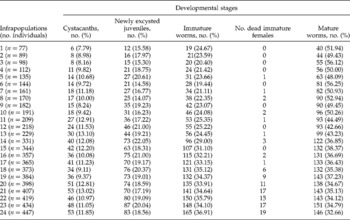

Table 1 The proportion of cystacanths, newly excysted juveniles, and immature and mature worms in 24 infrapopulations of Sclerocollum saudii.

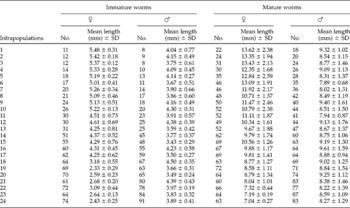

Table 2 The mean lengths of immature and mature worms, in 24 infrapopulations of Sclerocollum saudii.

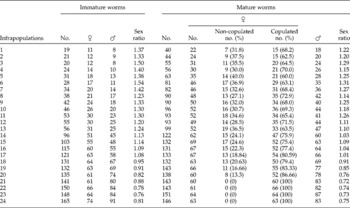

Table 3 The female–male ratio of immature and mature worms, in 24 infrapopulations of Sclerocollum saudii.

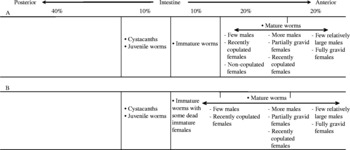

Sclerocollum saudii infrapopulations consisted of cystacanths, newly excysted juveniles and immature and mature worms. These stages were only found in the anterior 60% of the intestine of S. rivulatus, where they successively distributed in specified regions according to their maturity. In infrapopulations 1–17 (slight or moderate intensity), cystacanths and newly excysted juveniles were found solely in the sixth 10% of the intestine, immature worms were found solely in the fifth 10% of the intestine and mature worms were found solely in the first 40% of the intestine (fig. 1A). In larger infrapopulations (18–24) (high intensity), mature worms expanded their normal site posteriorly to become partly distributed with the immature worms (r s = 0.787953, P = 0.0002) (fig. 1B), where a differential mortality among immature females was constantly observed (table 1) (r s = 0.826786, P = 0.0001). This pattern of distribution was consistent from fish to fish.

Fig. 1 The distribution of cystacanths, newly excysted juveniles and immature and mature worms of Sclerocollum saudii along the intestine of Siganus rivulatus: (A) small and (B) large infrapopulations.

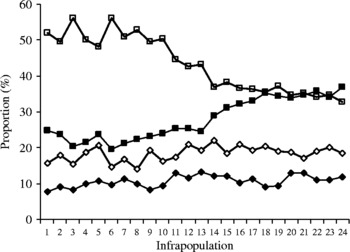

The proportions of each stage of the parasite were perfectly recorded through all infrapopulations (table 1). In infrapopulations 1–17, where the distribution was as in fig. 1A, the proportions of cystacanths (7.79–13.10%), newly excysted juveniles (15.58–22.05%), immature worms (19.44–33.15%) and mature worms (36.43–56.25%) followed a clear ascending order in each infrapopulation (fig. 2). This seemed to be normal and was more probably due to the continuing accumulation of infections and the duration of each stage. In larger infrapopulations (18–24) with mature worms partially existing in the site of immature ones (fig. 1B), the proportions of cystacanths and newly excysted juveniles were closely similar to those in the smaller infrapopulations, while the proportion of immature worms was significantly increased to reach 36.91% and that of the mature worms was significantly decreased to reach 32.66% of the infrapopulation.

Fig. 2 The proportion of cystacanths (closed diamonds), juveniles (open diamonds), immature worms (closed squares) and mature worms (open squares), in 24 infrapopulations of Sclerocollum saudii (see also table 1).

Worm length and female to male ratios

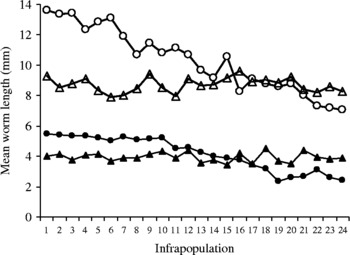

The mean lengths of immature and mature worms were separately recorded through all infrapopulations (table 2). In infrapopulations 1–17 (slight or moderate intensity) with immature and mature worms in separate sites in the fundamental niche (fig. 1A), the mean lengths of immature and mature females ranged from 4.25 to 5.48 and from 9.67 to 13.62 mm, respectively. In larger infrapopulations (18–24) (high intensity) with mature worms partially existing in the site of immature ones (fig. 1B), the mean lengths of immature and mature females were dramatically or gradually decreased to reach 2.43 and 7.04 mm, respectively, in the largest infrapopulation and, as mentioned before, a differential mortality among immature females was constantly observed in these cases (r s = 0.826786, P = 0.0001). The correlation between numbers of immature females and their mean lengths was strongly negative (r s = − 0.955841, P = 0.00 001) (fig. 3). Similarly, the correlation between numbers of mature females and their mean lengths was strongly negative (r s = − 0.969552, P = 0.00 001) (fig. 3), i.e. as the numbers of immature and mature females increased in the infrapopulation their mean lengths decreased. However, there was a strong positive correlation between mean lengths of immature and mature females (r s = 0.9226, P = 0.0001) (fig. 3). The mean lengths of immature and mature males seemed to be more stable, ranging from 3.43 to 4.50 and from 7.89 to 9.61 mm, respectively, through all infrapopulations. There were no significant relationships between numbers of males and their mean lengths, either for immature males (r s = 0.066522, P = 0.74 900) (fig. 4) or for mature males (r s = − 0.003484, P = 0.99 200) (fig. 4), or between mean lengths of immature and mature males (r s = − 0.069565, P = 0.73 380) (fig. 4). Moreover, there were no significant relationships between mean lengths of immature females and males (r s = 0.233913, P = 0.25 840) (fig. 5) or between mean lengths of mature females and males (r s = 0.118261, P = 0.56 860) (fig. 5). Combination of these results strongly suggests that in large infrapopulations of S. saudii there were density-dependent effects and competition between immature females (and probably between mature females), because their lengths seemed adversely sensitive to crowding stress, while immature and mature males seemed to be less affected or unaffected. However, the strong positive correlation between mean lengths of immature and mature females suggests that decreased body length of mature females observed in large infrapopulations was the consequence of density-dependent effects and competition between immature females. Thus, as the increment in the body length of immature and mature females decreased with density in large infrapopulations, the body of immature and mature males appeared to be slightly larger (table 2).

Fig. 3 The relationship between mean length and the number of immature (closed circles) and mature (open circles) females, in 24 infrapopulations of Sclerocollum saudii (see also table 2).

Fig. 4 The relationship between mean length and the number of immature (closed circles) and mature (open circles) males, in 24 infrapopulations of Sclerocollum saudii (see also table 2).

Fig. 5 The relationship between mean length of immature females (closed circles) and immature males (closed triangles) and mature females (open circles) and mature males (open triangles), in 24 infrapopulations of Sclerocollum saudii (see also table 2).

In S. saudii infrapopulations, the distribution of mature males was probably not random with respect to the length and position of mature females (fig. 1). This was clear in large infrapopulations, where most of the mature worms were found in groups along the anterior 40% of the intestine of S. rivulatus: in anterior groups, mature females were larger in length, mixed with few relatively large males and fully gravid; in intermediate groups, mature females were moderate in length, mixed with more males and some of them were partially gravid and the others were recently copulated; in posterior groups, mature females were small in length, mixed with few males (in small infrapopulations) or with relatively more males (in large infrapopulations), and some (in small infrapopulations) or all of them were recently copulated (in large infrapopulations). Thus, larger females seemed to be copulated in the anterior region of the fundamental niche prior to the smaller ones, which copulated successively next to them, according to their lengths. In all cases, males close to recently copulated females were relatively lager than other males found within or around the groups. Some small mature males with cement plug on their gonopores were found scattered between the groups, and no females were close to them; such homosexual rape may exclude the smaller mature males from copulating.

Female–male ratios of immature and mature worms were separately recorded through all infrapopulations (table 3). In infrapopulations (1–17), the female–male ratios of immature and mature worms were slightly or distinctly female-biased, ranging from 1.08 to 1.50 and from 1.01 to 1.31, respectively. In larger infrapopulations (18–24) (high intensity), where a differential mortality among immature females was constantly observed in the fifth 10% of the intestine (r s = 0.826786, P = 0.0001), the female–male ratios of immature and mature worms were slightly or distinctly male-biased, and significantly decreased to reach 0.76 and 0.72, respectively, in some large infrapopulations. The correlation between the female–male ratio of immature worms and infrapopulation size was strongly negative (r s = − 0.942584, P = 0.0001). Similarly, the correlation between female–male ratio of mature worms and infrapopulation size was strongly negative (r s = − 0.890, P = 0.0001), i.e. as the infrapopulation size increases, the number of immature males and consequently the number of mature males increases relative to the numbers of immature and mature females in an infrapopulation. Therefore, large infrapopulations of S. saudii are generally characterized by relatively more immature and mature males than found in small infrapopulations. However, there was a strong positive correlation between female–male ratios of mature and immature worms (r s = 0.956493, P = 0.0001). This result strongly suggests that the female–male ratio of mature worms is a consequence of that of the immature worms, and female–male ratio does not originate after the maturity of worms, but originates at earlier stages. Moreover, there was a strong negative correlation between female–male ratio and numbers of copulated females through all infrapopulations (r s = − 0.901957, P = 0.0001), i.e. as the female–male ratio decreases with infrapopulation size (male proportion increases), the number of copulated females increases in the infrapopulation.

Discussion

The fundamental niche of a gastrointestinal helminth parasite is the distributional range of sites within the gut, where the parasite occurs in single-species infections (Poulin, Reference Poulin2001). In the present study, S. saudii infrapopulations were found distributed in the anterior 60% of the intestine of S. rivulatus and never observed in the other intestinal regions. Thus, S. saudii infrapopulations were distributed in a well-defined fundamental niche along the intestine of this fish; absence of other intestinal helminth parasites excludes the confounding influence of interspecific interaction.

Most acanthocephalan species show a clear site preference for a particular region in the alimentary canal of their definitive hosts (Crompton, Reference Crompton1973; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2006). This site may relate to the physico-chemical conditions in the alimentary canal (Crompton, Reference Crompton1970, Reference Crompton1973; Taraschewski, Reference Taraschewski2000), to special stimuli required for eversion of the larval stage (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Broughton and Hine1976) or to specific nutritional requirements (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2006). However, the preferred site may extend in response to increasing parasite intensity (Kennedy & Lord, Reference Kennedy and Lord1982; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1984). These concepts are clear in the present study, where the distribution of the developing and mature stages of S. saudii in the anterior 60% of the intestine of S. rivulatus was highly specified and showed different site preferences. In small infrapopulations (slight or moderate intensity), the distribution followed a clear trend consistent from fish to fish, perhaps resulting from recruitment dynamics, and clearly demonstrates that the developing stages of S. saudii migrate towards the anterior 40% of the intestine while they mature, copulate and reproduce. Excystment of active juveniles from acanthocephalan cystacanths has been examined in only four species (see Graff & Kitzman, Reference Graff and Kitzman1965; Awachie, Reference Awachie1966; Lackie, Reference Lackie1974; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Broughton and Hine1978). It is thought to be mainly stimulated superficially by the bile of the host or by the osmotic pressure of the surrounding medium. The exact role of the bile is not fully understood (Khanna, Reference Khanna2004). In S. saudii, excystment of active juveniles occurred in the sixth 10% of the intestine of S. rivulatus, and the presence of immature worms in the middle region of the intestine may be because this region is usually rich in simple nutrients that can be absorbed by the body wall of acanthocephalans, as suggested by Petrochenko (Reference Petrochenko1956). In large infrapopulations (high intensity) with mature worms partially existing in the site of immature ones (fig. 1B), a differential mortality was only, and consistently, observed among the immature females. Thus, immature females seemed to be adversely affected or more sensitive to crowding stress than immature males and mature worms. This result strongly suggests density-dependent effects and intraspecific competition among immature females. Such a competition, which leads to individual mortality in high-density infrapopulations, may contribute to regulating the size of infrapopulations through the operation of density-dependent establishment and survival mechanisms (Uznanski & Nickol, Reference Uznanski and Nickol1982; Brown, Reference Brown1986; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2006; Poulin, Reference Poulin2006).

In small infrapopulations of S. saudii, the proportions of cystacanths, newly excysted juveniles, immature and mature worms showed a clear ascending order in each infrapopulation. This seemed to be normal, and was more probably due to the continuing accumulation of infections and the duration of each stage. In large infrapopulations, with mature worms partially existing in the site of immature ones (fifth 10% of the intestine) (fig. 1B), the proportions of cystacanths and newly excysted juveniles were similar to those in the small infrapopulations, while the proportions of immature worms were significantly increased and those of the mature worms were significantly decreased. Thus, in large infrapopulations (high intensity), crowding stress adversely affected the growth of some immature worms, retarding their normal maturation. This result and the differential mortality observed among immature females at the same site (probably for the same reason) strongly suggest density-dependent effects and intraspecific competition (at least for space) among immature worms, or between immature and mature worms. These observations greatly support the experimental finding of Uznanski & Nickol (Reference Uznanski and Nickol1982) that parasite activation (excystment of juveniles from cystacanths) is a density-independent process, but establishment and survival are apparently density-dependent.

Density-dependent reductions in mean worm length (growth or fecundity) have been reported in several studies (e.g. Szalai & Dick, 1989; Shostak & Scott, Reference Shostak and Scott1993; Richards & Lewis, Reference Richards and Lewis2001; Dezfuli et al., Reference Dezfuli, Volponi, Beltrami and Poulin2002; Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Giari, Simoni and Dezfuli2003; Hassanine & Al-Jahdali, Reference Hassanine and Al-Jahdali2008). Such a decrease in length (fecundity) contributes to the regulation of the parasite population by the availability of infective stages for all infrapopulations (Poulin, Reference Poulin2006). The dramatic decrease in the lengths of immature and mature females in large infrapopulations of S. saudii with mature worms partially existing in the site of immature ones strongly suggests density-dependent effects and competition between females. This suggestion is reinforced by the differential mortality among immature females which was constantly observed in this region of the intestine, and by the strong negative relationships between the numbers of immature females and their mean lengths, and between the numbers of mature females and their mean lengths, throughout the infrapopulations. However, the strong positive correlation found between the mean lengths of immature and mature females may suggest that decreased body length of mature females observed in large infrapopulations was a consequence of density-dependent effects and competition between immature females. In contrast, the mean lengths of immature and mature males seemed to be more stable through all infrapopulations. However, no significant relationships were found between the mean lengths of immature females and males, and between the mean lengths of mature females and males. Therefore, density-dependent effects and competition in large infrapopulations of S. saudii appeared to be restricted to immature females (and probably mature females). Thus, as the increment in the body length of immature and mature females decreased with density in large infrapopulations, the body length of immature and mature males appeared to be slightly larger (see table 2). At present, there is no plausible reason to explain why the length of immature and mature females was adversely sensitive to a crowding effect, while the length of immature and mature males was not. However, according to Sasal et al. (Reference Sasal, Jobet, Faliex and Morand2000) and Dezfuli et al. (Reference Dezfuli, Volponi, Beltrami and Poulin2002), female acanthocephalans are larger than males and the greater nutrient requirements associated with their length and maturity could make them more sensitive to crowding than males.

Acanthocephalans are polygamous parasites, and in certain species, mature worms form a sexual congress, i.e. aggregate within small groups for mating in the intestine of their host (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Martens and Nickol1997). In these groups, males may be choosy when mating with females, preferring larger females (Lawlor et al., Reference Lawlor, Read, Keymer, Parveen and Crompton1990); male body length seems to be advantageous as larger males have been shown to have greater access to females (Parshad & Crompton, Reference Parshad and Crompton1981; Andersson, Reference Andersson1994; Sinisalo et al., Reference Sinisalo, Poulin, Högmander, Juuti and Valtonen2004); and a single male can mate with several females (Crompton, Reference Crompton1974). After mating, males secrete cement to plug the female gonopore (Crompton, Reference Crompton1970, Reference Crompton, Crompton and Nickol1985), preventing further inseminations, at least temporarily (Whitfield, 1970). This reproductive behaviour could lead to male–male competition for access to females, mostly when the proportion of males in an infrapopulation increases (Sasal et al., Reference Sasal, Jobet, Faliex and Morand2000). In the present study, mature worms of S. saudii were mostly found in non-random groups within the fundamental niche and their characteristics agreed implicitly with these concepts. The groups were successively arranged according to the length of females: anterior groups consisted of larger, fully gravid females (all fully gravid) and few relatively large males; intermediate groups consisted of moderate-sized females (some partially gravid and others recently copulated) and more males; posterior groups consisted of small females (some or all recently copulated) and few, or relatively more, males. Hence, the distribution of mature males seems to be dynamic, with males always seeking new mating opportunities, and thus moving towards non-copulated females. In all cases, males close to recently copulated females were relatively larger than other males found within or around the groups. This observation agrees with the finding of Sinisalo et al. (Reference Sinisalo, Poulin, Högmander, Juuti and Valtonen2004), that in acanthocephalan infrapopulations males close to non-copulated females are larger than those close to copulated females. In addition, some small, mature males with cement plugs on their gonopores were found scattered between the groups, and no females were close to them. Such homosexual rape or indiscriminate mating was observed previously by Abele & Gilchrist (Reference Abele and Gilchrist1977) and Richardson et al. (Reference Richardson, Martens and Nickol1997) and may exclude the smaller mature males from copulating. These observations suggest that the male–male competition for access to females may be intense in S. saudii infrapopulations and may select for large males. Thus, sexual selection, i.e. intensity of male–male competition for access to females (Ghiselin, Reference Ghiselin1974; West Eberhard, Reference West Eberhard1983) may play a vital role in determining the spatial distribution of female and male worms of S. saudii within the fundamental niche. In acanthocephalans, males move down the intestine, fertilizing females as they do so (Awachie, Reference Awachie1966), or males may be choosy when mating with females, preferring larger females located in the anterior intestine (Lawlor et al., Reference Lawlor, Read, Keymer, Parveen and Crompton1990). These suggestions seem partially true in the present study, where larger females of S. saudii were located at the beginning of the anterior intestine and appeared to be copulated prior to the smaller ones, which were copulated successively next to them, according to their positions and lengths, in the fundamental niche.

The primary sex ratio of acanthocephalans in their intermediate hosts (arthropods) is supposed to be equilibrated (1:1) (Crompton, Reference Crompton, Crompton and Nickol1985), while sex ratios of acanthocephalans in their definitive hosts are typically female-biased (Valtonen, Reference Valtonen1983; Crompton, Reference Crompton, Crompton and Nickol1985; Poulin, Reference Poulin1997a). It has been suggested that, in female-biased infrapopulations, the greater proportion of females may be because acanthocephalan females survive longer than males following the infection of hosts, i.e. due to the higher mortality of males compared with females (Crompton, Reference Crompton1970; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1972; Crompton et al., Reference Crompton, Keymer and Arnold1984; Amin, Reference Amin1986; Brattey, Reference Brattey1988). Such differential mortality occurs after sexual maturity (Abele & Gilchrist, Reference Abele and Gilchrist1977), and males' higher mortality rate may due to male–male competition for access to females (Sasal et al., Reference Sasal, Jobet, Faliex and Morand2000). The exact mechanism leading to male-biased sex ratios in acanthocephalan infrapopulations is still unclear. Undoubtedly, the fundamental niche of a gastrointestinal helminth parasite has a carrying capacity, i.e. has a capacity for a certain maximum number of worms that can exist within it without intraspecific competition (Hassanine & Al-Jahdali, Reference Hassanine and Al-Jahdali2008). In small infrapopulations of S. saudii the female–male ratios were female-biased; where the intensity was slight or moderate, the immature and mature worms were in separate sites within the fundamental niche and the density-dependent effects were not noticeable. In these infrapopulations, the numbers of worms were probably lower than the carrying capacity of the fundamental niche. In large infrapopulations the female–male ratios were male-biased; where the intensity was high, the mature worms existed partially in the site of immature ones (fifth 10% of the intestine), and the density-dependent effects or intraspecific competition between immature females were clearly noticeable; leading to differential mortality among them in this region of the intestine. In these infrapopulations, the numbers of worms were probably higher than the carrying capacity of the fundamental niche and triggered competition between immature females. Thus, infrapopulation size ( = intensity of infection), carrying capacity of the fundamental niche, density-dependent effects and the subsequent intraspecific competition and differential mortality among immature females are the main factors determining the female–male ratio in S. saudii infrapopulations. However, female–male ratios of mature and immature worms seemed to be closely related and similar in each infrapopulation, a result strongly suggesting that the female–male ratio of mature worms is a consequence of that of the immature worms, and the female–male ratio does not originate after the maturity of worms, but originates at earlier stages. Moreover, the strong negative correlation between female–male ratios and numbers of copulated females through the infrapopulations indicates that as the female–male ratio decreases with infrapopulation size (male proportion increases), the number of copulated females increases in the infrapopulation, Thus high-density infrapopulations create male-biased operational sex ratios, allowing most mature females to copulate.

Comparative data suggest that as the infrapopulation size increases, the sex ratio should become less female-biased to increase the probability of mating, and at the same time the length of mature males relative to mature females should increase in response to stronger male–male competition for access to females (May & Woolhouse, Reference May and Woolhouse1993; Poulin, Reference Poulin1997a, Reference Poulinb). These expected patterns were clearly observed in the present study, where mature males in small infrapopulations of S. saudii were relatively fewer and distinctly smaller than mature females, while mature males in large infrapopulations were relatively more and slightly larger than mature females. The slight increase in the length of mature males may not be due to the additional growth of males in response to male–male competition for access to females, because mean lengths of immature males were also slightly larger than those of immature females, and mean lengths of mature males seemed to be stable through all infrapopulations. In fact, mature males of S. saudii did not increase in length (as indexed by lower female–male ratios) in response to male–male competition for access to females, but appeared to be larger than mature females, which previously had been decreased in length through the crowding stress or competition that occurred during their immature stage.

Generally, the differential mortality and reduction in mean body length observed among the immature females, and most of the other results, strongly suggest that infrapopulation self-regulation is through density-dependent mechanisms, in which immature females may play a key role.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia, for continued encouragement and support. We should also like to extend our appreciation to the staff of Rabigh-Faculty of Science and Arts, King Abdulaziz University, for their help during the collection of the material.