Introduction

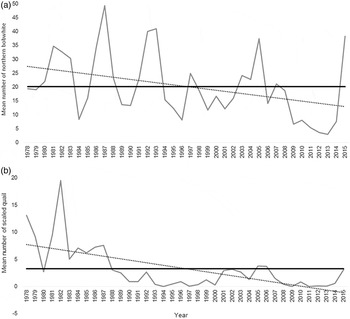

The northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) and scaled quail (Callipepla squamata) are two of the most important upland gamebird species in Texas because of their popularity with hunters and also due to their economic importance to communities (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Rollins and Reyna2012). Unfortunately, both species have experienced population declines, especially since about 1994 (fig. 1) (Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 2016). The decline of northern bobwhite and scaled quail throughout their native range has been well documented over the past few decades (Sauer et al., Reference Sauer, Hines, Fallon, Pardieck, Ziolkowski and Link2013). The Breeding Bird Survey has shown a yearly decline in northern bobwhites of >4% and scaled quail have shown a yearly decline of 3% from 1966 to 2013 (Sauer et al., Reference Sauer, Hines, Fallon, Pardieck, Ziolkowski and Link2013). The decline has been attributed to a variety of factors, including loss of suitable habitat, changes in agricultural practices, fragmentation and variations in weather (Bridges et al., Reference Bridges, Peterson, Silvy, Smeins and Ben Wu2001; Rollins, Reference Rollins and Brennan2007; Hernández et al., Reference Hernández, Brennan, DeMaso, Sands and Wester2013). While it is likely that there are several inter-related factors causing this decline, the role of parasitic infections and diseases has not been thoroughly researched as a potential causal factor. To the contrary, disease and parasites have long been dismissed as a problem in quail management (Lehmann, Reference Lehmann1984; Peterson, Reference Peterson and Brennan2007).

Fig. 1. Trends in the mean number of (a) northern bobwhite and (b) scaled quail from roadside surveys in the Rolling Plains ecoregion of Texas from 1978 to 2015; (—) long-term mean values; (···) long-term population trend (modified from Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 2016).

In the Rolling Plains ecoregion, the decline of quail has been especially puzzling considering that habitat conditions have remained relatively stable (Rollins, Reference Rollins2000, Reference Rollins and Brennan2007). Cantu et al. (Reference Cantu, Rollins and Lerich2005) noted that the greatest decline of scaled quail happened in the Rolling Plains ecoregion. These species typically exhibit a ‘boom and bust’ life cycle that repeats approximately on a 5-year cycle (Hernández et al., Reference Hernández, Kelley, Arredondo, Hernández, Hewitt, Bryant and Bingham2007; Lusk et al., Reference Lusk, Guthery, Peterson and Demaso2007). Despite favourable weather conditions during the summer of 2010, an anticipated irruption never occurred. The paucity of quail left landowners, hunters and researchers looking for reasons why quail were declining.

The importance of parasites and disease has long been dismissed as a concern for the management of quail populations, despite evidence that parasites are capable of regulating wildlife populations (Lehmann, Reference Lehmann1984; Tompkins et al., Reference Tompkins, Dobson, Arneberg, Begon, Cattadori, Greenman, Heesterbeek, Hudson, Newborn, Pugliese, Rizzoli, Rosá, Rosso, Wilson, Hudson, Rizzoli, Grenfell, Heesterbeek and Dobson2002). Research addressing parasites of Texas quail is lacking, with only sporadic efforts since the 1940s and early 1950s (Peterson, Reference Peterson and Brennan2007). Without a specific reason linked to the decline of quail in Texas, the need for answers sparked a large-scale quail research initiative. The project, known as Operation Idiopathic Decline (OID), was a multiyear collaborative effort that investigated disease, pathogens, contaminants and parasites in quail living throughout the Rolling Plains ecoregion of Texas and Oklahoma.

One of the most interesting findings from OID was the number of quail that were infected with eyeworms (Oxyspirura petrowi) (Dunham et al., Reference Dunham, Bruno, Almas, Rollins, Fedynich, Presley and Kendall2016). This is a heteroxenous nematode, requiring an intermediate host to complete its life cycle, which inhabits the orbital cavity, nasal sinuses, the Harderian and lacrimal glands, and underneath the eyelids and nictitating membrane of quail (Saunders, Reference Saunders1935; Addison & Anderson, Reference Addison and Anderson1969; Dunham et al., Reference Dunham, Soliz, Fedynich, Rollins and Kendall2014; Bruno et al., Reference Bruno, Fedynich, Smith-Herron and Rollins2015). Oxyspirura spp. were first reported in bobwhites in the Rolling Plains ecoregion of Texas in 1965 (Jackson & Green, Reference Jackson and Green1965); however, infection has been documented in other galliformes including ring-necked pheasants (Phasianus colchicus), lesser-prairie chickens (Tympanuchus pallidcinctus) and ruffed grouse (Bonasas umbellus), to name a few (McClure, Reference McClure1949; Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Highby and Carlson1949; Robel et al., Reference Robel, Walker, Hagen, Ridley, Kemp and Applegate2003). Prior to OID, little was known about O. petrowi in bobwhites from the Rolling Plains, except that infected birds had been documented behaving erratically and flying into stationary objects such as fences and buildings (Jackson, Reference Jackson1969). These observations, coupled with the high prevalence and intensities noted, led to speculation that O. petrowi infection may be more of a problem than previously thought. This finding has led to further investigations to determine if O. petrowi poses a health or fitness problem in infected quail. Subsequent studies confirmed that O. petrowi infections result in inflammation, oedema, acinar atrophy, conjunctivitis, and damage to the cornea and eye ducts/glands of northern bobwhites from Texas (Dunham et al., Reference Dunham, Soliz, Fedynich, Rollins and Kendall2014; Bruno et al., Reference Bruno, Fedynich, Smith-Herron and Rollins2015).

During the summer of 2013, an O. petrowi epizootic was documented in Mitchell County, Texas, with infection in adult bobwhites ranging from 91 to 100% throughout the entire summer (Dunham et al., Reference Dunham, Soliz, Fedynich, Rollins and Kendall2014). These eyeworm infections were much higher than the 61–79% (Jackson & Green, Reference Jackson and Green1965) and 57% (Villarreal et al., Reference Villarreal, Fedynich, Brennan and Rollins2012) previously documented in quail in the Rolling Plains. Subsequent research has also suggested that O. petrowi is now endemic throughout the region, with infections being documented in 29 counties throughout the Rolling Plains of Texas and Oklahoma (Dunham et al., Reference Dunham, Bruno, Almas, Rollins, Fedynich, Presley and Kendall2016).

The caecal worm (Aulonocephalus pennula) is another parasitic nematode of concern in the Rolling Plains. It is an intestinal parasite found in the intestines and caeca of its host (Chandler, Reference Chandler1935; Peterson, Reference Peterson and Brennan2007). Intestinal parasites, much like A. pennula, have been documented to cause inflammation of the caecal mucosa, inactivity, weight loss, reduced growth and even death in game birds (DeRosa & Shivaprasad, Reference DeRosa and Shivaprasad1999; Nagarajan et al., Reference Nagarajan, Thyagarajan and Raman2012). Caecal worms have not been studied extensively and little is known about the potential consequences that caecal worm infections pose for quail species in west Texas. Rollins (Reference Rollins1980) observed evidence of gross pathological changes in the caeca of quail with >100 caecal worms. Additionally, drought has been suggested to increase the intensity of caecal worm infection in quail (Lehmann, Reference Lehmann1984), which is alarming considering that the Rolling Plains experienced a long-term drought during 2010–2013. While few studies have looked at caecal worm infections in quail, they did document high caecal worm infections (>80% prevalence, mean intensities >80 worms) in both northern bobwhite and scaled quail (Lehmann, Reference Lehmann1984; Rollins, Reference Rollins and Brennan2007; Landgrebe et al., Reference Landgrebe, Vasquez, Bradley, Fedynich, Lerich and Kinsella2007).

The aim of the present study was to monitor helminth infections in quail in Mitchell County, Texas, to gain a better understanding of O. petrowi infection dynamics as well as monitor A. pennula infection in the same populations. Given the potential damage that these parasites can cause to their host, it is imperative that we monitor them in the long term to assess how they may influence quail inhabiting the Rolling Plains.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study area was a 120,000-ha privately owned ranch in Mitchell County, Texas (32°7′45″N, 100°59′6″W) that lies within the Rolling Plains ecoregion. The primary interest of the ranch is cattle production, with some focus on oil production and wind energy. Mitchell County has a mean annual daily temperature that ranges from 35.6°C in July to −1.1°C in January, with an annual precipitation of 50 cm/year (Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, 2016). Much of the Rolling Plains ecoregion is comprised of rangelands that are dominated by juniper (Juniperus pinchotti), prickly pear (Opuntia spp.) and honey mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa); grassland species such as silver bluestem (Bothriochloa saccharoides), sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula) and buffalo grass (Buchloe dactyloides); and woody species such as sand shinnery oak (Quercus havardii), netleaf hackberry (Celtis reticulata), catclaw (Acacia spp.) and lotebush (Ziziphus obtusifolia) (Rollins, Reference Rollins and Brennan2007).

Collection and examination of quail

Northern bobwhites and scaled quail were trapped from March to October in both 2014 and 2015 along the same 9.6-km transect that was used to document an O. petrowi epizootic in the study of Dunham et al. (Reference Dunham, Soliz, Fedynich, Rollins and Kendall2014). This area was chosen because it had suitable quail habitat and was near a minimally travelled gravel ranch road. Forty-five welded-wire walk-in double funnel traps (91.4 × 60.9 × 20.3 cm) were placed near and/or alongside a minimally travelled ranch road (32°10′N, 101°55′W) at intervals of 0.4–0.8 km. All traps were set next to a tree or bush and covered with available vegetation to ensure they were properly shaded. Each trap was left open and baited using milo (Sorghum bicolor) for a minimum of 2 weeks prior to trapping. During trapping sessions, all traps were monitored daily from 2 h after sunrise to 1 h before, or at, sunset. All captured quail were transported to The Institute of Environmental and Human Health (TIEHH) aviary at Texas Tech University and held in 25 × 61-cm cages for a maximum of 10 days prior to examination. Quail were provided milo, grit and water ad libitum while being held. During their 10-day holding period, all quail were aged, sexed, weighed, cloacal swabbed, and faeces and blood were collected. Cloacal swabs, faeces and blood were collected for additional research needs, not suitable for this manuscript, which is the reason quail were held for 10 days. By day 10, all quail were euthanized and examined for O. petrowi and A. pennula infection. Voucher specimens of O. petrowi (northern bobwhite: 1420519; scaled quail: 1420520) and A. pennula (northern bobwhite: 1420521; scaled quail: 1420522) were deposited in the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History (Suitland, Maryland, USA).

During the months of November–February in 2014 and 2015, we also collected bobwhite and scaled quail via hunter-donations from the same study ranch where quail were trapped. All quail were hunted using a dog and harvested with a shotgun. After being shot, the head and one wing from each donated quail were removed and placed into individually numbered plastic bags. The caeca were also removed from each quail and placed in a separate plastic bag. All bags were then properly labelled, frozen and provided to the Wildlife Toxicology Laboratory for analysis of eyeworm and caecal worm infection. Quail were aged (adult vs. juvenile) according to the presence or absence of buffed tips on the primary wing coverts, whereas gender was determined based on the coloration of the feather on the head and plumage of the face and throat (Wallmo, Reference Wallmo1956; Lyons et al., Reference Lyons, Schroeder, Robb and Silvy2012).

Parasite examinations

Eyeworms were extracted using a modified technique developed at TIEHH (Dunham et al., Reference Dunham, Soliz, Fedynich, Rollins and Kendall2014). After euthanasia and/or after hunter-donated specimens were properly thawed, the examination started for all quail by first lifting each eyelid with forceps and looking underneath for O. petrowi. Next, the nictitating membrane was located and examined using forceps. After the surface examination of both eyes, the eyelids, beak and excess tissue were removed to allow the eyeball, associated ducts/glands and tissues to be removed. The eyeball and excised tissues were placed into a Petri dish filled with Ringer's solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Both the lacrimal and Harderian gland, along with the excised tissues, were removed from the eyeball, teased apart and examined using a magnifying ocular headset (Donegan DA-5 OptiVisor headband magnifier, 2.5 × magnification, 20 cm focal length; Donegan Optical, Lenexa, Kansas, USA) because immature eyeworms can be difficult to see without magnification. Once all of the glands, ducts and tissues had been examined, the head of the quail was dipped several times in the Ringer's solution, which causes any potential eyeworms that are still attached within the orbital cavity to release and fall to the bottom of the Petri dish.

Aulonocephalus pennula were extracted by carefully removing the caeca out of the quail and/or by thawing the donated caeca and placing them on a 20-mesh sieve. Next, the caeca were cut into several smaller sections and examined by slowly teasing apart the tissues and caecal contents, and looking for parasites. To help in the recovery, an ocular headset, light and water squirt bottle were used. The squirt bottle was used to flush the organics and parasites out of the caeca and the sieve was used to filter out the faeces and expose only the caecal worms. After all of the small sections of caecum were examined, A. pennula were transferred into a Petri dish filled with Ringer's solution and counted. Once the examination was complete, all parasites were placed in a 70% ethanol with 8% glycerol solution for storage.

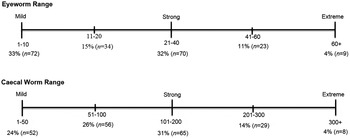

Hypothesized strength of infection

Since 2010, there has been a considerable amount of effort to understand the dynamics of O. petrowi and A. pennula in the Rolling Plains ecoregion of Texas and Oklahoma. Northern bobwhite and scaled quail have been collected throughout the region and we have noticed that infection levels vary greatly between the samples. Recent studies have documented eye pathology in quail infected with parasites (Dunham et al., Reference Dunham, Soliz, Fedynich, Rollins and Kendall2014; Bruno et al., Reference Bruno, Fedynich, Smith-Herron and Rollins2015), which has led to speculation that parasite infection can influence the quail population. Using data from Dunham et al. (Reference Dunham, Soliz, Fedynich, Rollins and Kendall2014, Reference Dunham, Bruno, Almas, Rollins, Fedynich, Presley and Kendall2016) and data collected from the present study, we have begun to hypothesize mild, strong and extreme infection strength for both O. petrowi and A. pennula (fig. 2). Due to the added burden that parasites can have on their host, less-infected quail would be expected to live longer. We expect that as the level of parasite infection increases there is a likelihood that these quail have reduced survivability.

Fig. 2. Hypothesized strength (mild, strong and extreme) of eyeworm Oxyspirura petrowi and caecal worm Aulonocephalus pennula infection in the northern bobwhite inhabiting the Rolling Plains ecoregion of Texas, 2014–2015.

Data analysis

Prevalence, mean abundance, mean intensity and range of O. petrowi and A. pennula infection were calculated for both northern bobwhite and scaled quail. Analysis was conducted on the combined total of captured and hunter-donated quail for each species. To determine if parasite abundance was influenced during times of precipitation, rainfall data were collected from our study location, being recorded daily by the ranch manager using multiple rain gauges spread throughout the study ranch. A Kruskal–Wallis test was used to determine if there was a significant difference in mean abundance of infection between years, sex and age of both species of quail (R Development Core Team, 2015). Prevalence of infection is defined as the number of quail infected with the parasite divided by total number of quail examined (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lafferty, Lotz and Shostak1997). Mean abundance refers to the number of parasites found in the quail examined divided by the total number of quail examined, whereas mean intensity is defined as the average number of the parasites of interest in infected quail (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lafferty, Lotz and Shostak1997). Significance was determined at P ≤ 0.05 and means are reported as mean ± SE.

Results

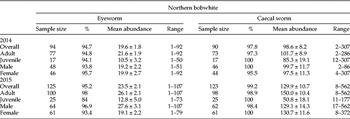

Between 2014 and 2015, a total of 208 of the 219 captured/hunter-donated northern bobwhites examined for O. petrowi (95%) and 210 of the 213 examined for A. pennula (99%) were infected. A maximum of 107 O. petrowi (approximately 50% immature) and 562 A. pennula were documented in a single bobwhite. Northern bobwhites averaged 19.6 ± 1.8 eyeworms (95%) and 98.6 ± 8.2 caecal worms (98%) in 2014 and 23.5 ± 2.1 eyeworms (95%) and 129.9 ± 10.7 caecal worms (99%) in 2015. Adult bobwhites had on average more eyeworms and caecal worms than juveniles in both 2014 and 2015 (table 1). There was no significant difference in eyeworm (χ2 61 = 53.8, P = 0.73) and caecal worm (χ2 147 = 144.4, P = 0.55) infection between sexes.

Table 1. Prevalence (%), mean abundance (± SE), and range of eyeworm (Oxyspirura petrowi) and caecal worm (Aulonocephalus pennula) by host age and sex from the northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) captured in Mitchell County, Texas, USA 2014–2015.

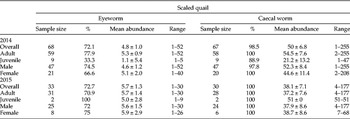

From 2014 to 2015, a total of 73 of the 101 captured/hunter-donated scaled quail examined for O. petrowi (72%) and 96 of the 97 examined for A. pennula (99%) were infected. A maximum of 52 O. petrowi and 255 A. pennula were found in single scaled quail. Scaled quail had on average 4.8 ± 1.0 eyeworms (72%) and 50 ± 6.8 caecal worms (99%) in 2014 and 5.7 ± 1.3 eyeworms (73%) and 38.1 ± 7.1 (100%) caecal worms in 2015. Eyeworm and caecal worm infection was similar across adult and juvenile scaled quail in both years (table 2). There was no significant difference in eyeworm (χ2 20 = 9.2, P = 0.98) and caecal worm (χ2 59 = 52.4, P = 0.72) infection between the sexes in scaled quail.

Table 2. Prevalence (%), mean abundance ( ± SE) and range of eyeworm (Oxyspirura petrowi) and caecal worm (Aulonocephalus pennula) by host age and sex from the scaled quail (Callipepla squamata) captured in Mitchell County, Texas, USA, 2014–2015.

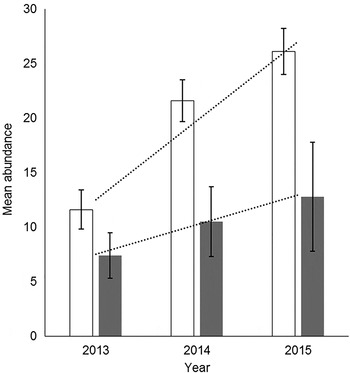

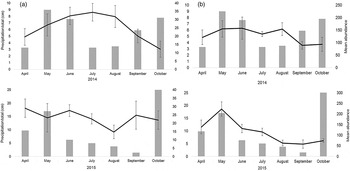

There was a significant difference in eyeworm infection between northern bobwhite and scaled quail (χ2 62 = 113.7, P < 0.001) but no significant difference in caecal worm infection between these species of quail (χ2 172 = 185.2, P = 0.23). Since 2013, there has been a gradual increase in average O. petrowi mean abundance and range of infection in adult and juvenile bobwhites throughout our study area (Dunham et al., Reference Dunham, Soliz, Fedynich, Rollins and Kendall2014) (fig. 3). Both eyeworm and caecal worm mean abundances in bobwhites peaked during late the summer months then decreased by the late autumn and winter months, corresponding with the cumulative monthly rainfall totals in both 2014 and 2015 (fig. 4). Both O. petrowi and A. pennula infection varied from month to month in both years for scaled quail. Only 4% of sampled quail had a level of infection rated as ‘extreme’ for both O. petrowi and A. pennula, while roughly 80% of all quail in our study area had only a mild to limited strong infection level (fig. 2).

Fig. 3. The mean abundance (± SE) of Oxyspirura petrowi in adult (clear bars) and juvenile (grey bars) northern bobwhite from Mitchell County, Texas, USA; (…) trend in mean abundances from 2013 to 2015 (Dunham et al., Reference Dunham, Soliz, Fedynich, Rollins and Kendall2014).

Fig. 4. Monthly precipitation (grey bars) and mean abundances (± SE) of (a) the eyeworm Oxyspirura petrowi and (b) the caecal worm Aulonocephalus pennula in the northern bobwhite from Mitchell County, Texas, USA in 2014 and 2015.

Discussion

A recent surge in parasite studies in bobwhite and scaled quail has raised speculation in terms of parasite influence on quail. Parasites have long been dismissed as a problem in quail; however, recent documentation of heavy parasitic infection concomitant with ‘quail decline’ suggests a possible causal relationship. The results of this study confirm that northern bobwhite and scaled quail inhabiting our study area are heavily infected with both O. petrowi and A. pennula. Within our study area, northern bobwhites were significantly more infected with O. petrowi than scaled quail (northern bobwhite >90%, scaled quail >70%). Despite infection being so prevalent throughout the region, with some parasites reaching epizootic levels in certain areas, the knowledge base on these two parasites remains relatively low due to the lack of parasite studies in quail.

Both O. petrowi and A. pennula are prevalent in bobwhite and scaled quail throughout the Rolling Plains ecoregion of Texas and western Oklahoma. Approximately 15% of bobwhites sampled in the present study averaged >40 O. petrowi per bird, with only 4% averaging more than 60. As many as 107 eyeworms (approx. 50% immature) were found in a single bobwhite and 52 eyeworms in a single scaled quail, both of which were the highest recorded O. petrowi infections documented in these species of quail. High levels of A. pennula were also found in both species of quail, with more than 500 found in a single northern bobwhite and more than 250 in a single scaled quail from our study ranch. Given the documented problems related to A. pennula infections, and with a heavy infection being documented in both northern bobwhite and scaled quail, this parasite may be as hazardous to quail as significant O. petrowi infections. Examination of the pathology of the caeca was out of the scope of the present project and pathology observations of A. pennula infection were not undertaken. However, Rollins (Reference Rollins1980) did observe haemorrhaging in the caeca of bobwhites harbouring >100 caecal worms.

Eyeworm and caecal worm infections in bobwhites peaked during the summer months in both 2014 and 2015 then decreased by late autumn, which corresponds with the rise in precipitation. Peak transmission of many nematodes with a heteroxenous life cycle typically coincides with the wet season (May–June in the Rolling Plains) when intermediate hosts are most plentiful (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Kellogg and Doster1980). With the potential increase in intermediate host availability, due to the rise in precipitation, there is also an increased chance for quail to become infected. Cumulative monthly rainfall totals during our experiment increased from April to May then slowly dropped off throughout the summer months, before increasing again in the early autumn, which coincided with our infection data (fig. 4).

While we have been collecting data from both O. petrowi and A. pennula, most of the focus has been on O. petrowi infection in the northern bobwhite. Given the difference in parasite infection in both quail species, we speculate that the primary host of these parasites is the northern bobwhite. Rollins (Reference Rollins1980) reported greater infections of caecal worms in scaled quail that were sympatric with bobwhites than allopatric populations of scaled quail. Severe pathological implications have been documented in quail with infections ranging from 1 to 61 O. petrowi (Bruno et al., Reference Bruno, Fedynich, Smith-Herron and Rollins2015); however, significant inflammation and haemorrhaging within the nasal-lacrimal and eye gland/ducts was observed in northern bobwhites with as few as 40 eyeworms (Dunham et al., Reference Dunham, Soliz, Fedynich, Rollins and Kendall2014, Reference Dunham, Soliz, Brightman, Rollins, Fedynich and Kendall2015). Finding O. petrowi in all the months sampled, and with their range in size, suggests that these parasites have the potential to live inside the host for long periods of time, indicating that infection is continuous in nature and likely cumulative until the host dies.

The primary areas where O. petrowi is encountered in birds are open fields, submarginal grasslands and marshlands, suggesting that infection is probably dependent on the occurrence of intermediate hosts that are restricted to a particular habitat (Pence, Reference Pence1972). With O. petrowi infection being documented at epizootic levels in particular areas, as well as in 29 counties throughout the ecoregion, it is likely that the prevalence of infection will increase. Friend et al. (Reference Friend, McLean and Dein2001) suggested that parasites can reduce host abundance during epizootic events that have high host mortality. Additionally, parasite eggs and infective-stage larvae have been documented to remain viable in the environment for several months, which further increases the chance of infection as parasites would be present in these locations for long periods of time (Lund, Reference Lund1960; Draycott et al., Reference Draycott, Parish, Woodburn and Carroll2000). Recent research by Kistler et al. (Reference Kistler, Hock, Hernout, Brake, Williams, Downing, Dunham, Kumar, Turaga, Parlos and Kendall2016) revealed that one intermediate host can carry as many as 90 L3 infective-stage O. petrowi larvae, suggesting that consumption of only one or two infected arthropods would be enough to lead to a strong or even extreme infection. The transmission of parasites from one organism to another depends on host availability, so by increasing the host density the likelihood for transmission increases (Hudson & Dobson, Reference Hudson, Dobson, Hudson and Rands1988).

Given the increased infection in the present study and evidence presented in recently published manuscripts (Dunham et al., Reference Dunham, Soliz, Fedynich, Rollins and Kendall2014, Reference Dunham, Bruno, Almas, Rollins, Fedynich, Presley and Kendall2016; Bruno et al., Reference Bruno, Fedynich, Smith-Herron and Rollins2015), we believe that these quail are experiencing similar, if not more, irritation and/or damage from their increased parasite infection. In terms of strength of O. petrowi and A. pennula infection in quail inhabiting this ecoregion, we believe that our hypothesized infection levels are a plausible reflection of what is happening. With <4% of samples of quail having an extreme infection for both parasites during this study, the results strongly suggest that heavily infected quail are likely dropping out of the population. Roughly 70% of all quail sampled had a mild to strong level of parasite infection, which was expected because they may have fewer problems associated with eye pathology and a higher parasite tolerance; however, as infection levels rise, their chances of surviving are most likely reduced (fig. 2).

The population of quail declined steadily in the Rolling Plains ecoregion from 2007 to 2014. In the midst of this decline, the Rolling Plains has experienced a long-term drought, which has been suggested to increase caecal worm intensity in quail (Lehmann, Reference Lehmann1984). Undoubtedly, a sustained drought had a major impact on quail abundance, but our studies documented a concurrent O. petrowi epizootic event that may have exacerbated the impact of the drought (Dunham et al., Reference Dunham, Bruno, Almas, Rollins, Fedynich, Presley and Kendall2016). In 2015 there was an increase in quail populations throughout the Rolling Plains ecoregion, which we speculate was due to the decrease in the availability of potential intermediate hosts because drought conditions likely suppressed them. We hypothesize that decreasing the availability of intermediate hosts likely reduces the chances of obtaining a parasitic infection, thus leading to an increase in the quail populations.

Our study continued to reveal that northern bobwhite and scaled quail inhabiting the Rolling Plains ecoregion are heavily infected with both eyeworm and caecal worm parasites. The present study also documented the most O. petrowi ever found in both northern bobwhite and scaled quail. Additional studies are under way to continue to monitor O. petrowi infection dynamics, in order to determine their role in the latest quail irruption, as well as to understand O. petrowi and A. pennula infection dynamics throughout the entire boom–bust cycle of northern bobwhite and scaled quail. More research is warranted to study the infection dynamics and life history of these parasites, in an effort to determine whether either (or both) parasite species have the ability to influence both individual- and population-level abundance of quail throughout the Rolling Plains ecoregion of Texas.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Rolling Plains Quail Research Foundation for funding this project. We thank the employees of our study site for providing lodging and ranch access, and all of the quail hunters who donated specimens for our examinations. Thank you to the Wildlife Toxicology Laboratory personnel for their field and laboratory assistance. Lastly, we thank the reviewers for their time, comments and consideration of this manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Rolling Plains Quail Research Foundation.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

All quail were trapped and handled according to Texas Parks and Wildlife permit SRP-1098-984 and Texas Tech University Animal Care and Use protocol 13066-08.