Introduction

The Atlantic Forest is one of the most degraded and fragmented areas of tropical forest biomes, with its remaining vegetation representing 12.4% of the original area (INPE, 2019). It extends from Rio Grande do Norte state in the northeast to Rio Grande do Sul in the south of Brazil along the east coast and extends inland to eastern Paraguay and the Misiones province in Argentina. Although it is a global biodiversity hotspot for conservation (Conservation International, 2021), there is still a large pressure caused by urbanization and agricultural activities in the surroundings of forest remnants. These activities may facilitate the encounter of humans and domestic animals with wild animals (Corrêa & Passos, Reference Corrêa, Passos, Fowler and Cubas2008), allowing parasites to find new hosts and environments (Daszak et al., Reference Daszak, Cunningham and Hyatt2000) and, consequently, opening new routes of transmission at the wildlife–human interface (Wells et al., Reference Wells, Gibson, Clark, Ribas, Morand and McCallum2018). Moreover, biotic factors such as host characteristics and abiotic factors, such as the type of environment, may alter the spatial and temporal distribution of the parasites, influencing their transmission potential (Combes, Reference Combes2001).

Generalist host species are expected to be able to survive in disturbed or degraded areas, such as the common opossums, and end up becoming more abundant (Kajin et al., Reference Kajin, Cerqueira, Vieira and Gentile2008; Gentile et al., Reference Gentile, Cardoso, Costa-Neto, Teixeira and D'Andrea2018). Thus, among marsupials, common opossums stand out for their large geographical distribution, dominance in disturbed areas and importance for public health (Bezerra-Santos et al., Reference Bezerra-Santos, Ramos, Campos, Dantas-Torres and Otranto2021). They can act as potential reservoirs of several pathogens that cause zoonoses, such as trypanosomatids (Xavier et al., Reference Xavier, Roque, Bilac, Araújo, Costa-Neto, Lorosa and Jansen2014; Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Xavier and Roque2015), Leptospira (Fornazari et al., Reference Fornazari, Langoni, Marson, Nóbrega and Teixeira2018) and Toxoplasma gondii (Fornazari et al., Reference Fornazari, Teixeira, da Silva, Leiva, de Almeida and Langoni2011), and play important ecological roles in ecosystems (Cantor et al., Reference Cantor, Ferreira, Silva and Setz2010). Two species of common opossum occur in the Atlantic Forest: the white-eared opossum Didelphis albiventris Lund, 1840 and the black-eared opossum Didelphis aurita Wied-Neuwied, 1826 (Cáceres et al., Reference Cáceres, de Moraes Weber and Melo2016). Didelphis albiventris is a didelphid marsupial with an ample distribution occurring in Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, Paraguay and Bolívia (Cáceres et al., Reference Cáceres, de Moraes Weber and Melo2016). In Brazil, it occurs in different environments of the Atlantic Forest, Caatinga, Cerrado, Pantanal and Pampa biomes in open and deciduous forest formations, including agricultural and urban areas (Cáceres et al., Reference Cáceres, de Moraes Weber and Melo2016).

Several studies have reported the occurrence of helminth species in D. albiventris (Quintão e Silva & Costa, Reference Quintão e Silva and Costa1999; Müller, Reference Müller2005; Pinto et al., Reference Pinto, Mati and Melo2014; Ramos et al., Reference Ramos, Santos and Freitas2016; Zabott et al., Reference Zabott, Pinto, Viott, Gruchouskei and Bittencourt2017). However, there is a lack of information concerning the structure of helminth communities of this mammal host species, especially under changing environments.

A relatively recent approach employed in the study of parasite communities is metacommunity analysis (Mihaljevic, Reference Mihaljevic2012). This approach aims to understand the pattern of species distribution – that is, the community structure, along an environmental gradient, analysing the elements of metacommunity structure (EMS) (Leibold & Mikkelson, Reference Leibold and Mikkelson2002). The set of local communities potentially linked by the dispersal of their species on a larger spatial scale forms a metacommunity (Leibold et al., Reference Leibold, Holyoak and Mouquet2004). Considering parasites, a metacommunity is the set of infracommunities of a given host species (parasites of an individual host), which create an environmental gradient (i.e. resource gradient that varies among hosts) influencing the occurrence and distribution of their parasites. Thus, the ecology of host–parasite interactions can be studied using this analysis to explain the dispersal dynamics of parasite species and how they are structured in the environment. This study aimed to describe the helminth fauna and to analyse the helminth community structure of the common opossum D. albiventris in two extreme areas of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, one in the northeast and the other in southern Brazil (3000 km apart).

We investigated the influence of host sex, body mass and age, locality and helminth species richness on the abundance and prevalence of the most prevalent helminth species. We also include herein a compiled list of the helminth fauna of D. albiventris based on published studies. We tested two hypotheses herein. Considering that heterogeneity among individual hosts concerning infection exposure would affect their encounters with parasites and their posterior establishment (Poulin, Reference Poulin2013), we hypothesized that: helminth prevalence and abundance are influenced by host sex, age and body mass, locality and helminth species richness. This hypothesis is based on the assumption that intraspecific variation in host characteristics may be essential for parasite persistence, influencing host–parasite interactions in a given community (Runghen et al., Reference Runghen, Poulin, Monlleó-Borrull and Llopis-Belenguer2021). We also hypothesize that parasite species and abundance are non-randomly distributed among hosts (Poulin, Reference Poulin2014). We expect that individual variation in host characteristics influences the distribution pattern of the parasites along the metacommunities, resulting in non-random structures at the infracommunity scale. A previous study of the helminth metacommunity structure of the congener D. aurita in different types of environments showed that helminths were non-randomly distributed (Costa-Neto et al., Reference Costa-Neto, Cardoso, Boullosa, Maldonado and Gentile2019).

Materials and methods

Study area

This study is part of a comprehensive survey project on the biodiversity of Atlantic Forest fauna and its parasites. Opossum captures were made in two localities, one in the municipality of Mamanguape, Paraíba state, in northeast Brazil, and another in the municipality of Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul state, in southern Brazil.

In Mamanguape, sampling was carried out in areas of secondary and Tabuleiro Atlantic Forest at the Guaribas Biological Reserve (REBIO Guaribas) (6°40′39″S, 35°07′51″W). REBIO Guaribas is a conservation unit of 4000 ha (ICMBio, 2003) and one of the last remaining preserved areas of Atlantic Forest in north-eastern Brazil, although it also presents characteristics of a disturbed environment and advanced successional stages in some areas. The study was carried out in areas of lowland semideciduous seasonal forest vegetation (Figueiredo et al., Reference Figueiredo, Barros and Delciellos2017), which are surrounded by sugar cane crops. The climate of the region is humid tropical with oceanic influence transitional of rainfall regimes, classified as As, Am or even Aw, within a few kilometres, according to the Köpen classification (Francisco et al., Reference Francisco, Medeiros, Santos and Matos2015), with high temperatures and seasonal rainfall concentrated in winter (June–September).

In Porto Alegre, sampling was carried out in peridomicile areas near forest fragments (30°2′55.22″S, 51°7′30.74″W). The areas comprised the localities of Vila Laranjeiras (30°2′57.82″S, 51°7′51.65″W), Morro Santana (30°2′55.22″S, 51°7′30.74″W), Morro da Polícia (30°4′57.24″S, 51°11′26.28″W) and at the campus of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (30°4′14.73″S, 51°7′16.35″W). The climate of the region is humid subtropical, without a dry season and with hot summers, Cfa according to the Köppen classification (Ayoade, Reference Ayoade1986).

Sampling methods

The opossums were collected in Tomahawk® live-traps (Hazelhurst, WI, USA) (16 × 5 × 5 inches). In Mamanguape, six transects were established with 15 capture points, with one trap placed on the ground at each point and three on the understorey at each transect. Captures were made during ten consecutive nights in June 2014 and April 2015. In Porto Alegre, five transects were established with 20 capture points and one with ten points. Captures were made during five consecutive nights in April 2018. The capture effort was 1080 trap-nights for the former locality and 550 trap-nights for the latter.

The opossums were identified by external morphology, weighed, measured and had their sex and degree of tooth eruption registered. The animals were submitted to euthanasia for helminth recovery as follows. The opossums were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/mL) associated with xylazine hydrochloride (20 mg/mL) in a 1:1 proportion at a dose of 0.1 mL/100 g. When the animal was completely anesthetized, 19.1% potassium chloride was applied by intracardiac injection at a dose of 2 mL/kg. The specimens were preserved through taxidermy and were housed as voucher specimens at the Mammal Collection of the Federal University of Paraíba in João Pessoa (specimens from Mamanguape) and the Laboratory of Biology and Parasitology of Wild Mammal Reservoirs at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Rio de Janeiro (specimens from Porto Alegre).

The animals were captured under the authorization of the Brazilian Government's Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity and Conservation (ICMBio, licence numbers 40869-1 and 13373-1). Captures and animal handling were performed according to the Ethical Committee on Animal Use of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (CEUA licence number LW-39/2014) and followed the standard protocols of biosafety (Lemos & D'Andrea, Reference Lemos and D'Andrea2014).

Helminth recovery and identification

The presence of helminths was investigated in the viscera, thoracic and abdominal cavities, pelvis and musculature of the marsupials. The recovered helminths were washed with saline (0.85% sodium chloride). Nematodes were fixed in AFA solution (93 parts 70% ethanol, 5 parts 0.4% formol and 2 parts 100% acetic acid) and heated to 65°C. Some specimens were stored in ethanol for DNA extraction. The trematodes and cestodes were compressed in cold AFA (Amato et al., Reference Amato, Walter and Amato1991).

Specimens were counted using a stereoscopic microscope. The nematodes were cleared with lactophenol or 50% glycerol/alcohol and identified under an optical microscope (Zeiss Axioscope A1 coupled to an Axiocam MRc digital camera, Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany). Some of the trematodes and cestodes were stained with Langeron's carmine, differentiated with 0.5% hydrochloric acid, dehydrated in an increasing alcohol series, cleared in methyl salicylate and mounted in Canada balsam as permanent preparations (Amato et al., Reference Amato, Walter and Amato1991).

The helminths were identified using morphological characteristics, as described by Khalil et al. (Reference Khalil, Jones and Bray1994), Gibson et al. (Reference Gibson, Jones and Bray2002), Anderson et al. (Reference Anderson, Chaubaud and Willmott2009) and publications of species descriptions. The specimens were deposited in the scientific collection of helminths at the Laboratory of Biology and Parasitology of Wild Mammal Reservoirs at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Rio de Janeiro.

Data analysis

The mean abundance, mean intensity and prevalence of each species of helminth in each locality were calculated according to Bush et al. (Reference Bush, Lafferty, Lotz and Shostak1997). The mean abundance was considered as the total number of parasites divided by the number of hosts analysed. The mean intensity was calculated as the total number of parasites divided by the number of infected hosts. Prevalence was considered as the proportion of the number of hosts infected in relation to the number of hosts analysed. The sex ratio of the most abundant helminth species was tested if it differed from 1:1 using the χ 2 contingency test. Total richness was considered the number of helminth species recovered, and mean species richness was considered the mean number of helminth species in infracommunities.

The influence of host sex, host age, body mass, locality and helminth species richness on helminth species abundance or prevalence was tested using generalized linear models (GLMs). In addition, the influence of these variables on the total abundance of helminths found in each infracommunity (all species gathered) was also investigated. Models containing all possible combinations of the variables were tested, and the best models were chosen using the corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc), in which the plausible models presented ΔAICc ≤ 2. The GLM analysis for abundance followed a Gaussian distribution, and for prevalence, a binomial distribution. This analysis was performed for helminth species whose prevalence was higher than 70%. This analysis was performed using the vegan package (Oksanen et al., Reference Oksanen, Blanchet and Friendly2020) in R software version 4.0.5 (R Core Team, 2021). For host age determination, animals were divided into young (without complete development of tooth eruption) and adult (with complete development of tooth eruption) groups according to Macedo et al. (Reference Macedo, Loretto, Vieira and Cerqueira2006).

The helminth metacommunity structure was investigated at the infracommunity level, considering each individual host as a site and evaluating the three elements of EMS – coherence, turnover and boundary clumping (Leibold & Mikkelson, Reference Leibold and Mikkelson2002; Presley et al., Reference Presley, Higgins and Willig2010). This analysis was performed for both each locality and the entire data set.

The coherence element tests whether species respond to the same environmental gradient, quantifying the number of embedded absences (absences localized between two species occurrences) on a species incidence matrix ordered by reciprocal averaging. When the coherence element was significant and positive (i.e. fewer absences embedded than expected by chance), turnover and boundary clumping were also assessed. When the coherence was not statistically significant, a random pattern of species distribution was identified, indicating that species did not respond to the same environmental gradient. When the coherence was statistically significant and negative (i.e. with more embedded absences than expected by chance), a checkerboard pattern was found, which suggests competitive exclusion.

The turnover element determines whether the processes that structure the diversity lead to substitution or loss of species along the gradient and is calculated by the number of species replacements in the incidence matrix. A turnover value significantly lower than expected by chance is consistent with nested distributions, indicating loss of parasite species in the metacommunity, so that species-poor communities are subsets of species-rich communities. When the turnover value is higher than expected by chance, the structure observed may be consistent with three different patterns. The Clementsian distribution is characterized by compartments or groups with similar species compositions within each group. The Gleasonian distribution is characterized by species-specific responses to the environmental gradient, but coincident across the metacommunity due to casual similarities in environmental requirements. Evenly spaced distribution indicates metacommunities with a strong interspecific competition. Boundary clumping is used to identify which of these structures fits the observed pattern.

Boundary clumping quantifies the overlap of species distribution limits in the environmental gradient, which can be clumped (when the index value is greater than 1), hyperdispersed (when the index is less than 1) or random (when boundary clumping is not statistically significant) (Presley et al., Reference Presley, Higgins and Willig2010; Braga et al., Reference Braga, Oliveira and Cerqueira2017). In addition to these distributions, other patterns called Quasi-structures, analogous to the idealized structures, are also considered when positive coherence and non-statistically significant turnover are observed (Presley et al., Reference Presley, Higgins and Willig2010). The EMS analysis was performed in MATLAB R2021a software (MathWorks, 2021) using EMS Script (Higgins, Reference Higgins2008).

Beta-diversity – that is, change in community composition between sites (Whittaker, Reference Whittaker1960) – was calculated between areas concerning species composition and abundance, according to the decomposition in Baselga (Reference Baselga2010, Reference Baselga2017). Beta-diversity indicates the degree of similarity between areas, and its components indicate whether there is more replacement (turnover) or loss of species and individuals (nestedness) along the environmental gradient – in this case, between areas. In addition, differences between observed and estimated values of beta-diversity and its components were statistically evaluated for both abundance and species composition at the infracommunity scale, for each locality separately (Mamanguape and Porto Alegre). This analysis was performed using beta.sample and beta.sample.abund functions, in which 1000 random resamplings of 10 infracommunities were performed, evaluating whether the proportion of samples that differed from the expected were random, following Baselga (Reference Baselga2017). This analysis was performed in the betapart package (Baselga et al., Reference Baselga, Orme, Villeger, Bortoli and Leprieur2018) in R software version 4.0.5 (R Core Team, 2021).

Results

Forty specimens of D. albiventris were captured, 24 in Mamanguape (20 males and four females) and 16 in Porto Alegre (four males, 11 females and one without sex record that was not included in the GLM analysis). Ninety-five per cent of the hosts (38) were infected by at least one helminth species, and no host was infected with all helminth species.

The total helminth species richness was 11 for Mamanguape and nine for Porto Alegre. The mean species richness considering both locations was 4.12. For Mamanguape, the mean species richness was 4.21, ranging from zero to eight, while for Porto Alegre, it was 4.0, ranging from zero to six. Seven species of the phylum Nematoda were identified: Aspidodera raillieti Travassos, 1913, Cruzia tentaculata (Rudolphi, 1819) Travassos, 1917, Trichuris didelphis Babero, 1960 and Trichuris minuta (Rudolphi, 1819) in the large intestine; Turgida turgida (Rudolphi, 1819) Travassos, 1919 in the stomach; Travassostrongylus orloffi Travassos, 1935 and Viannaia hamata Travassos, 1914 in the small intestine. Two species of Platyhelminthes were also identified: the digenean trematodes Brachylaima advena Dujardin, 1843 and Rhopalias coronatus (Rudolphi, 1819) Stiles & Hassall, 1898 in the small intestine. Furthermore, three helminth morphospecies were also recovered: the nematodes Hoineffia sp. and Viannaia sp., and a cestode in the small intestine. The identification of these specimens at the species level was hampered by the lack of males for the two former and by poor preservation of the latter.

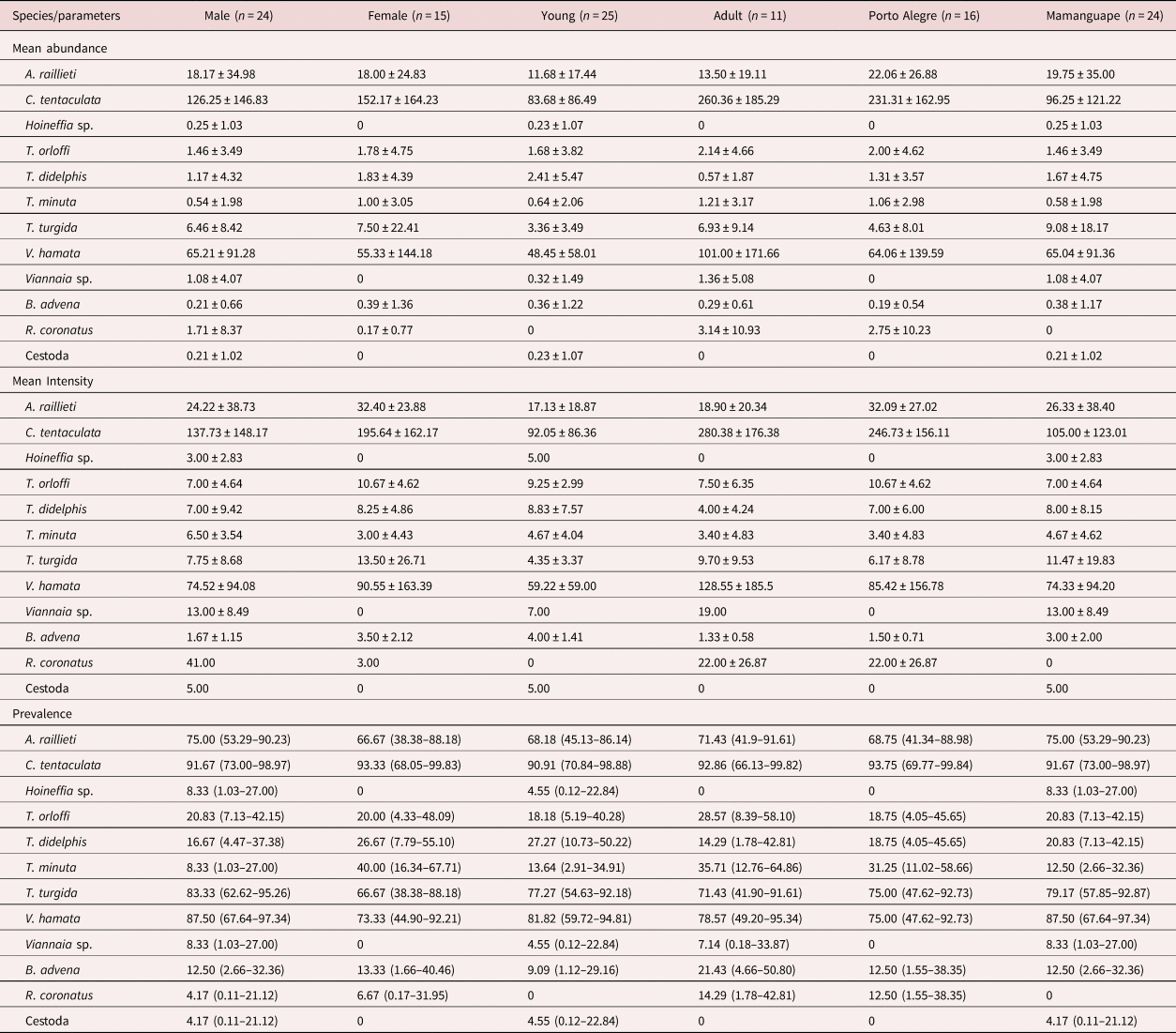

We recovered 4698 specimens of adult helminths from Mamanguape and 5270 from Porto Alegre. The nematodes C. tentaculata and V. hamata were the most abundant species (table 1). The prevalence was higher for the nematodes A. raillieti, C. tentaculata, T. turgida and V. hamata (table 1).

Table 1. Mean abundance and intensity ± standard deviation and prevalence (95% confidence interval) stratified by host sex, host age and locality for helminths of Didelphis albiventris in Mamanguape and Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Cruzia tentaculata, A. raillieti and V. hamata had significantly more females than males (χ 2 = 100.19 and P = 0.0001; χ 2 = 26.30 and P = 0.0001; χ 2 = 205.90 and P = 0.0001, respectively).

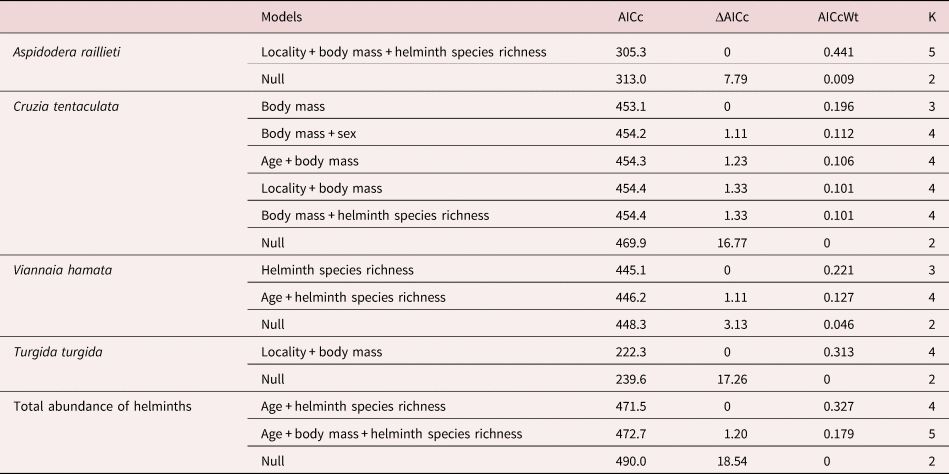

The GLM analysis showed that A. raillieti had a low abundance in hosts with larger body mass (table 2). Moreover, the abundance of A. raillieti was positively influenced by helminth species richness and by Porto Alegre locality (tables 1 and 2).

Table 2. Generalized linear models for the abundance of the most prevalent helminth species of Didelphis albiventris in Mamanguape and Porto Alegre, Brazil, in relation to host age, sex, body mass, helminth species richness and locality.

AICc, corrected version of Akaike information criterion; ΔAICc, difference between the model with smallest AICc and each model; AICcWt, Akaike weights; K, number of parameters of the model. Models considered plausible had ΔAICc ≤ 2. Only the models with ΔAICc ≤ 2 and the null models are included in the table.

For C. tentaculata, the GLM analysis showed larger abundance in hosts with larger body mass, larger helminth species richness and in the Porto Alegre locality, as plausible models included these variables (tables 1 and 2). Despite this, the abundance of this species was negatively influenced by host sex (male) and host age (young), indicating less abundance in young males (tables 1 and 2). Body mass was the most important variable, as it was present in all plausible models (table 2).

The abundance of V. hamata was positively influenced by helminth species richness, as observed in the GLM analysis (table 2), indicating an increase in abundance with increasing helminth species richness, and negatively influenced by host age (young), indicating less abundance in young hosts (tables 1 and 2).

The only plausible model observed in the GLM analysis of the abundance of T. turgida showed a positive influence of host body mass (table 2), indicating that the larger the host body mass, the larger the abundance of this helminth. In addition, it showed a negative influence of Porto Alegre locality (table 2), which showed less abundance of this helminth compared to Mamanguape (table 1).

The total helminth abundance was positively influenced by the helminth species richness and the host body mass in the GLM analysis (table 2), indicating an increase in helminth abundance with the increase in host body mass and helminth species richness. In addition, a negative influence of host age (young) was observed (table 2), indicating less helminth abundance in young hosts.

The GLM analysis for the prevalence of A. raillieti, C. tentaculata and V. hamata indicated the null model as a plausible model for all species (table 3). For T. turgida, the prevalence was positively influenced by body mass, host age (young) and host sex (male), indicating that this helminth mostly occurred in hosts with larger body mass and young males (tables 1 and 3).

Table 3. Generalized linear models for the prevalence of the most prevalent helminth species recovered from Didelphis albiventris in Mamanguape and Porto Alegre, Brazil, in relation to host age, sex, body mass helminth species richness for each infracommunity and locality.

AICc, corrected version of Akaike information criterion; ΔAICc, difference between the model with smallest AICc and each model; AICcWt, Akaike weights; K, number of parameters of the model. Models considered plausible had ΔAICc ≤ 2. Only the models with ΔAICc ≤ 2 and the null models are included in the table.

The helminth metacommunity analysis indicated a coherent structure when the two localities were analysed together and at the local scale only for Mamanguape (table 4; fig. 1a, b). A Gleasonian structure was found for the infracommunities of both localities together (fig. 1a), and a quasi-Gleasonian structure was found for the infracommunities of Mamanguape (fig. 1b). These patterns are characterized by more substitutions than species losses (table 4). When analysing the helminth infracommunities from Porto Alegre, a random pattern of distribution (non-statistically significant coherence) was observed (table 4; fig. 1c).

Fig. 1. Ordinated matrices for helminth metacommunities of Didelphis albiventris at the infracommunity scale, considering: (a) both localities together, Mamanguape (black sites) and Porto Alegre (grey sites); (b) Mamanguape; and (c) Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Table 4. Elements of the helminth metacommunity structure of Didelphis albiventris at the infracommunity scale, in Mamanguape and Porto Alegre, Brazil, separately, and for the two localities together.

Abs, embedded absences; Rep, observed replacements; MI, Morisita's Index; Mean, average of randomly generated matrices; SD, standard deviation; P, significance.

Helminth beta-diversity was low between localities either for abundance (0.231) or for species composition (0.20). For both, the turnover component was higher than the nestedness (abundance: turnover = 0.184, nestedness = 0.047; species composition: turnover = 0.111, nestedness = 0.089). However, the helminth beta-diversity was high among the infracommunities of Mamanguape, either for abundance (0.904) or for species composition (0.779), showing more turnover than nestedness (abundance: turnover = 0.700, nestedness = 0.204; species composition: turnover = 0.577, nestedness = 0.202). Considering Porto Alegre infracommunities, the helminth beta-diversity was also high, either for abundance (0.816) or for species composition (0.721), with more turnover than nestedness (abundance: turnover = 0.616, nestedness = 0.200; species composition: turnover = 0.603, nestedness = 0.118).

Considering the estimated beta-diversity based on 1000 random resamplings, the mean value for Mamanguape was 0.828 for abundance and 0.617 for species composition, with higher turnover (abundance: 0.538; species composition: 0.379) than nestedness (abundance: 0.290; composition: 0.238). Thus, the observed beta-diversity and turnover were significantly different from the expected values estimated by chance (P < 0.001 for both abundance and species composition) and turnover (abundance: P = 0.003; species composition: P < 0.001). Regarding nestedness, no significant difference was obtained between observed and randomly estimated values (abundance: P = 0.105; species composition: P = 0.308). The same pattern was observed in Porto Alegre infracommunities. The mean value for the estimated beta-diversity was 0.756 for abundance and 0.642 for species composition, with higher turnover (abundance: 0.523; composition: 0.512) than nestedness (abundance: 0.233; species composition: 0.130). As in Mamanguape, the observed values of total beta-diversity in Porto Alegre were statistically different from those generated by chance (P < 0.001 for both abundance and species composition), as well as the turnover rates (abundance: P = 0.037; species composition: P < 0.001). There was no significant difference between observed and estimated nestedness (abundance: P = 0.296; species composition: P = 0.350) in Porto Alegre.

Discussion

All helminth species identified in this study have already been reported parasitizing D. albiventris in Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay (supplementary table S1); however, the geographic distribution of several helminth species expanded with this study. Paraíba state is a new geographic distribution area for A. raillieti, B. advena, C. tentaculata, T. didelphis, T. minuta, T. orloffi, T. turgida and V. hamata. The municipality of Porto Alegre is a new geographic distribution area for A. raillieti, B. advena, C. tentaculata, R. coronatus, T. didelphis, T. minuta, T. orloffi, T. turgida and V. hamata. This is the first record of T. minuta in Rio Grande do Sul state. In addition, this is the first study to evaluate the pattern of metacommunity structure for the opossum D. albiventris, as well as the factors that mostly explained the variations in helminth species prevalence and abundance in this host.

The compiled list of the helminth fauna of D. albiventris includes 26 morphotypes of Nematoda, 15 of Trematoda, five of Cestoda and two of Acanthocephala, with 31 identified species overall (supplementary table S1).

Regarding the analysis of prevalence, abundance and intensity, other studies of the helminth community of D. albiventris also found higher values for C. tentaculata, T. turgida, A. railieti and V. hamata than for the other helminth species. Quintão e Silva & Costa (Reference Quintão e Silva and Costa1999) found the highest prevalence for C. tentaculata and T. turgida in Pampulha, Minas Gerais state, Brazil. Müller (Reference Müller2005) found the highest prevalence for C. tentaculata and the highest abundances and intensities for V. hamata, C. tentaculata and A. raillieti in Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul state. Zabott et al. (Reference Zabott, Pinto, Viott, Gruchouskei and Bittencourt2017) found the highest prevalence for T. turgida and C. tentaculata and the highest abundance for the latter in Palotina, Paraná state, Brazil. Another study with the congener host D. aurita also reported similar results, with C. tentaculata showing the highest prevalence and V. hamata showing the highest abundances and intensities in peri-urban and sylvatic environments, while T. turgida showed the highest prevalence and abundance in a rural environment in three localities in Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil (Costa-Neto et al., Reference Costa-Neto, Cardoso, Boullosa, Maldonado and Gentile2019).

The greater abundance of female specimens compared to males observed for C. tentaculata, A. raillieti and V. hamata may be related to an ecological strategy of reproduction for these species. A large number of females would release a large number of eggs, increasing the chances of contact of the infective stage with the host. This type of strategy is more common in species with polygamous mating systems (Poulin, Reference Poulin2007). However, the mating system of these helminths is still unknown. Other studies have found similar results for C. tentaculata (Müller, Reference Müller2005; Castro et al., Reference Castro, Costa-Neto, Maldonado Júnior and Gentile2017; Costa-Neto et al., Reference Costa-Neto, Cardoso, Boullosa, Maldonado and Gentile2019; Cirino et al., Reference Cirino, Costa-Neto, Maldonado Júnior and Gentile2020).

Concerning the influence of biotic factors and locality on parasitism, the larger abundance of A. raillieti and C. tentaculata in Porto Alegre may be related to the type of environment (periurban), which favours the abundance of D. albiventris, a generalist species that can survive in disturbed environments, contributing to the transmission of this parasite (Bezerra-Santos et al., Reference Bezerra-Santos, Ramos, Campos, Dantas-Torres and Otranto2021). Concerning host body mass, it was expected that specimens with larger body masses would be more parasitized because they would tend to harbour a larger number of parasites (Guégan et al., Reference Guégan, Lambert, Lévêque, Combes and Euzet1992; Poulin, Reference Poulin1995), which did not occur for A. raillieti. On the other hand, the larger abundance of C. tentaculata in individuals with larger body masses corroborates this hypothesis. Considering all helminth species, host body size was also one of the main factors influencing total helminth abundance, indicating that there is an accumulation of parasites as body size increases throughout the host lifetime.

In mammals, studies have shown that males normally present higher infection rates of helminths than females (Zuk & McKean, Reference Zuk and McKean1996). The higher infection rates of C. tentaculata in female hosts contradict the typical pattern and may indicate a larger exposure or susceptibility of females to this species. Other studies have recorded higher helminth infection rates in female small mammals (Simões et al., Reference Simões, Júnior, Olifiers, Garcia, Bertolino and Luque2014; Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Macabu, Simões, Maldonado Júnior, Luque and Gentile2019; Boullosa et al., Reference Boullosa, Cardoso, Costa-Neto, Teixeira, Freitas, Maldonado-Júnior and Gentile2020; Kersul et al., Reference Kersul, Costa and Boullosa2020). Regarding host age, C. tentaculata and V. hamata had lower abundances in young hosts. The same pattern was observed considering all species together. We hypothesize that young hosts would have less time to be exposed to parasites and, consequently, to progressively accumulate parasites over the host lifetime.

The positive influence of total helminth species richness on the abundance of A. raillieti, C. tentaculata and V. hamata and on the total helminth abundance may be because local communities were not saturated with species. Thus, the addition of new species (increased richness) would increase the abundance of parasites per host (Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Mouillot and George-Nascimento2003), and the abundance of these dominant species would not be influenced by the abundance of the others.

For T. turgida, the lower abundance in Porto Alegre may be related to the lower abundance and/or diversity of species that can act as an intermediate host of this helminth, since this species has an indirect life cycle. More preserved environments would have a greater diversity of host species and thus favour the transmission of this parasite in the locality of Mamanguape.

Regarding the prevalence of helminth species, we did not observe an influence of the analysed variables on the prevalence of A. raillieti, C. tentaculata and V. hamata, indicating that host sex, age, body mass and locality are not important determinants for the occurrence of these species in a given infracommunity. In contrast to T. turgida, the results for this species indicated that host age, sex and body mass influenced its occurrence.

The Gleasonian and quasi-Gleasonian patterns of community structure observed indicated that the helminth species are independently distributed along the infracommunities, probably due to the existence of intrinsic responses of each helminth species to the environmental gradient (Leibold & Mikkelson, Reference Leibold and Mikkelson2002), considering all the infracommunities in the study, and less evident for Mamanguape infracommunities. This pattern is based on the concept proposed by Gleason (Reference Gleason1926), where the structure of communities is based on species-specific idiosyncratic responses to the environment and random responses to one another. Thus, species coexistence in a given infracommunity is due to random similarities in environmental requirements.

The random distribution in the helminth metacommunity structure observed for Porto Alegre indicates that, in this area, helminth species do not respond to the same environmental gradient, which may be a result of distinct associations of species with environmental factors or with attributes of their hosts (Leibold & Mikkelson, Reference Leibold and Mikkelson2002). However, we also point out that this random pattern may be a result of the smaller number of hosts (number of local communities) found infected in this locality compared to Mamanguape.

The low beta-diversity observed between localities indicates a medium-high similarity regarding species composition and abundance between the two localities in extreme opposites of the Atlantic Forest biome. However, our results indicated high beta-diversity among individual hosts (infracommunities), which may be related to intraspecific variation in host characteristics. Moreover, a higher turnover was observed relative to nestedness values, indicating more species replacement than loss between localities and infracommunities, corroborating the Gleasonian pattern observed in the metacommunity structure. These results, together with the results of the GLM and the pattern of metacommunity structure observed, indicate a stronger influence of the host and the transmission dynamics among host individuals than the geographical distance and environmental factors on the community structure. Most likely, the speciation process of many of these helminths occurred together with the hosts, with subsequent expansion of their geographic distribution and host spectrum. Although climatic factors were not analysed, they may have some influence in shaping those communities. We highlight the importance of evaluating the evolution of parasitism and parasite sharing under climate change scenarios (Morales-Castilla et al., Reference Morales-Castilla, Pappalardo, Farrell, Aguirre, Huang, Gehman and Davies2021).

The species C. tentaculata, A. raillieti, V. hamata and T. turgida formed the core species of the component communities and mostly contributed to the helminth metacommunity structure. These results corroborate the study by Costa-Neto et al. (Reference Costa-Neto, Cardoso, Boullosa, Maldonado and Gentile2019), who also found the species C. tentaculata, A. raillieti and T. turgida as the core species of the component community for D. aurita, the other species of Atlantic Forest common opossum. The structuring pattern of the helminth metacommunity and the beta-diversity considering both localities indicated that differences among infracommunities are attributed to species substitutions instead of species losses, with species-specific and independent responses to the environmental gradient.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X21000791

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff and students of Laboratório de Biologia e Parasitologia de Mamíferos Silvestres Reservatórios at Fundação Oswaldo Cruz and Laboratório de Mamíferos at Universidade Federal da Paraíba who helped in the field work. We also thank Dr Paulo D'Andrea for the ICMBIO licence and for the coordination of Serviço de Referência em Taxonomia de Pequenos Mamíferos Reservatórios de Zoonoses at Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Porto Alegre sampling) and Dr R. Cerqueira for the coordination of the general project PPBio Rede BioM.A (Mamanguape sampling).

Financial support

This work was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq – PPBio Rede BioM. A (457524/2012-0), Instituto Oswaldo Cruz (IOC – FIOCRUZ), Serviço de Referência em Saúde at Fundação Oswaldo Cruz and Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biodiversidade e Saúde (IOC-FIOCRUZ). B.S.C. received grants from Instituto Oswaldo Cruz and from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Brazil, finance code 001. S.F.C.N. received grants from CAPES, Brazil, finance code 001. T.S.C. received grants from Inova Fiocruz/Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. R.G. received researcher grants from CNPq (304355/2018-6).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The animals were captured under the authorization of the Brazilian Government's Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity and Conservation (ICMBio, licence numbers 40869-1 and 13373-1). Captures and animal handling were performed according to the Ethical Committee on Animal Use of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (CEUA licence number LW-39/2014) and followed the standard protocols of biosafety (Lemos & D'Andrea, Reference Lemos and D'Andrea2014).