Introduction

Fasciolosis is a worldwide-spread zoonotic parasitic disease, mainly caused by Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica, which are parasitic in humans and animals (Mas-Coma et al., Reference Mas-Coma, Valero and Bargues2009). As a food-borne parasite, the adult F. hepatica is mainly parasitic in the hepatobiliary ducts of humans or animals. Thus, it feeds on host red blood cells, bile and liver tissue cells, and can cause pathologies such as hepatitis, cholecystitis and anaemia (Collins et al., Reference Collins, Stack and O'Neill2004). In recent years, with changes in the global climate and natural environment, the incidence rate of fasciolosis is increasing (Fox et al., Reference Fox, White and McClean2011). According to the World Health Organization, about 2.4 million people are infected with Fasciola species worldwide, and 180 million people are at risk of being infected (Marcos et al., Reference Marcos, Yi and Machicado2007). More than 300 million cattle and 250 million sheep have been infected with these parasites. As a result, this disease has been causing considerable economic loss to farmers and the ruminant industry (Mas-Coma, Reference Mas-Coma2005; Mehmood et al., Reference Mehmood, Zhang and Sabir2017).

At present, the control of fasciolosis of ruminants mainly relies on the chemical deworming drug Triclabendazole (Solana et al., Reference Solana, Meray Sierra and Scarcella2015). However, as the problems of drug resistance of F. hepatica and veterinary drug residues become more prominent, the control of this disease is becoming increasingly difficult (Kelley et al., Reference Kelley, Elliott and Beddoe2016). Therefore, it is imperative to develop a specific and sensitive approach for early diagnosis to control the occurrence of the disease. The traditional diagnostic method for fasciolosis is to examine the F. hepatica eggs in faeces or bile drainage. However, only the worm that enters the bile duct and matures (about 12 weeks after infection) will ovulate (Mas-Coma, Reference Mas-Coma2005). Therefore, the performance of parasitological diagnosis based on the inspection of eggs in faeces is unsatisfactory and not suitable for the early diagnosis of fasciolosis (Rondelaud et al., Reference Rondelaud, Dreyfuss and Vignoles2006). Recently, many studies have confirmed that F. hepatica excretory-secretory products (ESPs) have strong antigenicity and can be used as a candidate diagnostic antigen for the development of F. hepatica serological detection (Sampaio-Silva et al., Reference Sampaio-Silva, Da Costa and Da Costa1996; Carnevale et al., Reference Carnevale, Rodríguez and Santillán2001; Abdolahi Khabisi et al., Reference Abdolahi Khabisi, Sarkari and Moshfe2017). However, due to the limited number of worms, the natural F. hepatica ESPs antigens cannot be prepared in large quantities at present. Meanwhile, F. hepatica ESP is a mixed protein, and no standard preparation method is available. Although it has strong sensitivity, it is easy to cause cross-reactivity with the serum of other species, and, thus, there is some non-specificity (Cornelissen et al., Reference Cornelissen, de Leeuw and van der Heijden1992; Torres et al., Reference Torres and Espino2006). Therefore, screening and identifying highly specific and sensitive F. hepatica diagnostic antigens is essential for developing accurate and sensitive serological assays.

Xinjiang is one of China's five major pastoral areas, where the ruminant animal husbandry is an important pillar industry. At present, the number of sheep in Xinjiang is 39 million, and the number of cattle is 5.8 million. The sheep in Xinjiang are mainly grazing breeds, and the wide spread of fasciolosis has caused large economic losses to local animal husbandry. The main purpose of this study was to develop and evaluate a colloidal gold immunochromatographic assay (CGIA) for the detection of F. hepatica-specific antibodies in sheep. Here, F. hepatica recombinant proteins rCatL1D, rCatB4 and rMeCatL-B were prepared and evaluated as serodiagnostic antigens for detecting F. hepatica-specific antibodies, respectively, and rCatL1D was employed as a candidate diagnostic antigen to develop the CGIA method.

Materials and methods

Collection of serum samples

A total of 426 sheep grazing in the endemic areas of fasciolosis in Tianshan Mountain's pastoral area of Xinjiang were chosen and labelled; blood was then collected, and the serum samples were subsequently separated and numbered. These sheep were slaughtered in a slaughterhouse; the organs (liver and bile duct) were examined for F. hepatica worms, and the serotypes (positive or negative) of the numbered serum samples were determined based on the results of the worm examination. By this means, a total of 100 samples of F. hepatica-positive sera and 326 negative sera (including 18 F. hepatica-negative sera and 308 sera infected with other parasites) were obtained. Five Echinococcus granulosus (Eg)-positive sera were collected from the infected sheep; five Cysticercosis tenuicollis (Ct)-positive sera and five Toxoplasma gondii (Tg)-positive sera were provided by the Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences; five F. gigantica (Fg)-positive sera were kindly donated by Guangxi University; ten F. hepatica-negative sera and 35 F. hepatica-positive sera were donated by Shawan Veterinary Station and tested using the Sheep Fasciola hepatica-IgG ELISA kit (Beinuo, Shanghai, China).

Collection of F. hepatica worms

The worms collected from the livers and bile ducts of sheep were washed by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (supplementary fig. S1). Firstly, extraction DNA from worms using the TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China), then the ITS1 and ND1 genes were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequenced. The sequencing results were compared with the F. hepatica ITS1 and ND1 gene sequences in GenBank to confirm that the collected worms were F. hepatica.

Primers design and synthesis

Two pairs of specific primers P1–P2 and P3–P4 containing BamH I and Xho I restriction sites were designed according to the sequence of the CatL1D (EU835857.1) and CatB4 (KM099340.1) genes in GenBank. The dominant epitopes of the CatL1D and CatB4 genes were analysed using software such as ABCpred (http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/abcpred/) and DNAstar (http://www.onlinedown.net/soft/580665.htm), and primers P5–P8 for splicing by overlap extension PCR (SOE-PCR) reactions were designed based on the dominant epitopes (table 1).

Table 1. List of primer sequences used in this study.

Cloning of F. hepatica CatL1D and CatB4 genes and construction of MeCatL-B fusion gene

Total RNA was extracted from F. hepatica using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Germany), and RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a reverse transcription kit (TaKaRa, Osaka, Japan). The 981 bp CatL1D and 699 bp CatB4 genes were amplified by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) using cDNA as a template. Then, the dominant epitope-enriched segments of CatL1D (nucleotides 315–723 bp) and CatB4 genes (nucleotides 111–513 bp) were amplified by P5–P6 and P7–P8 primers, respectively. A MeCatL-B fusion gene of approximately 810 bp was constructed by fusing the dominant epitope encoding sequences of these two genes using SOE-PCR.

Preparation of F. hepatica recombinant proteins CatL1D, CatB4 and MeCatL-B

The CatL1D, CatB4 and MeCatL-B genes were cloned into pET-32a vectors (Invitrogen, California, USA), respectively, and the positive plasmids were screened by double-enzyme digestion and sequencing. The positive plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) competent cells (TaKaRa, Osaka, Japan), and sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis was performed after induction by 1.0 mmol/l isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (TaKaRa, Osaka, Japan). The expressed recombinant proteins were purified using a Ni2+ affinity chromatography column (GE Healthcare, Boston, USA), respectively, and confirmed by western blot. The sheep F. hepatica-positive serum was used as the primary antibody, while the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labelled rabbit anti-sheep IgG (Sigma, San Francisco, USA) was used as the secondary antibody.

Evaluation of the reactogenicity of recombinant proteins via indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The reactogenicity of recombinant proteins was determined by indirect ELISA, as described by Mokhtarian et al. (Reference Mokhtarian, Meamar and Khoshmirsafa2018). Briefly, the optimal concentration of rCatL1D (7 µg/ml), rCatB4 (10 µg/ml) and rMeCatL-B (12.5 µg/ml) protein of F. hepatica was determined by a preliminary checkerboard titration test. ELISA plates (Greiner Bio-One, Frickenhausen, Germany) were coated with 100 µl of each recombinant protein at 4°C overnight, respectively. After washing with PBS with tween-20 (PBST), the wells were blocked with solution containing 5% (w/v) skimmed milk powder for 2 h at 37°C. Following a second washing, 100 µl of 1:100 diluted sheep sera was added and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After another washing, 100 µl of 1:5000 diluted rabbit anti-sheep IgG-HRP (Sigma, San Francisco, USA) was added and the plates incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After an extensive washing with PBST, 100 µl of 3, 3′, 5, 5′-tetramethylbenzidine was added as chromogen/substrate solution. Following 20-min incubation in the dark, the enzymatic reaction was terminated by 0.2 mol/l H2SO4, and the OD450nm value was measured by a microplate reader.

A total of ten F. hepatica negative sera, 35 F. hepatica positive sera and five each of Eg-, Ct-, Tg- and Fg-positive sera were detected by indirect ELISA based on rCatL1D, rCatB4 and rMeCatL-B proteins, respectively. The recombinant protein with the strongest reactogenicity was chosen according to the OD450nm values of indirect ELISA.

Establishment of a CGIA

The composition of the CGIA is described as follows and shown in supplementary fig. S2. In brief, gold nanoparticles-Staphylococcal aureus protein A (Gold-SPA) complex was prepared according to the previous literature (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Jin and Chen2007). The gold-SPA complex was spread on a gold pad (Sangon, China) at 10 µl/cm2 and deposited at 37°C for 2 h. Then, rCatL1D protein and sheep IgG (Roche, Switzerland) were respectively labelled on the test line (T-line) and control line (C-line) on the nitrocellulose filter membrane (NC) membrane (Sigma, San Francisco, USA), followed by drying at room temperature for 2 h. The CGIA strip was assembled on polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plate in the order of absorbent pad, NC membrane, gold pad and sample pad (supplementary fig. S2), respectively. Then, the strips were stored in a desiccator at 4°C for future use. The serum to be tested was added to the sample pad, and the colour reaction was observed within 10 min. When the T-line and C-line were all coloured on the test strip, the result was considered positive; in contrast, if the T-line did not develop colour, while the C-line was coloured, the result was negative. If the T-line developed colour, and the C-line did not, or neither the T-line nor the C-line was coloured, the test was invalid.

Evaluation the performance of the CGIA test strip

Briefly, 35 F. hepatica-positive sera, ten F. hepatica-negative sera, five each of Fg-, Ct-, Tg- and Eg-positive sera were all diluted at a 1:16 dilution, and assayed by the CGIA test, respectively. Also, F. hepatica-positive serum was diluted with 0.2 mol/l PBS (1:1, 1:8, 1:16, …, 1:1024) to evaluate the performance of the CGIA test. Meanwhile, ten F. hepatica-negative sera were used as negative control and 0.2 mol/l PBS used as blank control.

Detection of clinical serum samples using CGIA test strip

A total of 426 clinical serum samples (100 F. hepatica positive sera and 326 negative sera confirmed by post-mortem inspection) were tested by the established CGIA method. The sensitivity, specificity and consistency rate of the CGIA method were evaluated according to the following formulas, respectively: sensitivity = true positive number/(true positive number + false negative number) × 100%; specificity = true negative number/(true negative number + false positive number) × 100%; consistency rate = (true positive number + true negative number)/total number of samples × 100%.

Results

The 981 bp CatL1D and 699 bp CatB4 genes were cloned and the 810 bp MeCatL-B fusion gene was constructed (supplementary figs S3 and S4). About 51 kDa of rCatL1D, 41.8 kDa of rCatB4 and 46 kDa of rMeCatL-B protein were detected by SDS-PAGE, respectively, and all three recombinant proteins were expressed in the form of inclusion bodies. Western blot analysis showed that all three recombinant proteins could specifically react with F. hepatica-positive serum (fig. 1), indicating that these recombinant proteins were antigenic.

Fig. 1. Analysis of expressed recombinant proteins CatL1D (A), CatB4 (B) and MeCatL-B (C) by SDS-PAGE and western blot. (A) Lane 1: induction of pET-32a (+) empty vector for 6 h; lane 2: lysate supernatant of rCatL1D after induced for 8 h; lanes 3–6: lysate precipitation of rCatL1D after induced for 2, 4, 6 and 8 h. (B) Lane 1: induction of pET-32a (+) empty vector for 6 h; lane 2: lysate supernatant of rCatB4 after induced for 8 h; lanes 3–6: lysate precipitation of rCatB4 after induced for 2, 4, 6 and 8 h. (C) Lane 1: lysate supernatant of rMeCatL-B after induced for 6 h; lanes 2–5: lysate precipitation of rMeCatL-B after induced for 2, 4, 6 and 8 h. Abbreviations: M, standard protein marker; P, sheep positive serum against Fasciola hepatica; N, negative control.

The evaluation of the F. hepatica rCatL1D, rCatB4 and rMeCatL-B proteins via indirect ELISA showed that the sensitivity and specificity of rCatL1D protein were 100% (35/35) and 96.67% (29/30), respectively, and the protein specifically reacted with Fg-positive sera. However, the sensitivity and specificity of rCatB4 and rMeCatL-B proteins were 94.29% (33/35), 80% (24/30), 91.43% (32/35) and 90% (27/30), respectively, and cross-reactive with both Fg- and Eg-positive sera (fig. 2), which indicated that the rCatL1D protein had the highest specificity and sensitivity.

Fig. 2. Assessment of specificity of rCatL1D (A), rCatB4 (B) and rMeCatL-B (C) protein via indirect ELISA. Note: the sera were diluted at 1:100, the ELISA reaction plate coated with rCatL1D, and proteins rCatB4 and rMeCatL-B had the best detection effect when at this concentration. The cutoff line of ELISA plates coated with rCatL1D, rCatB4 and rMeCatL-B proteins were set at 0.275, 0.245 and 0.275, respectively. Abbreviations: Fh PS, Fasciola hepatica-positive sera; Fh NS, F. hepatica-negative sera; Fg PS, F. gigantica-positive sera; Ct PS, Cysticercus tenuicollis-positive sera; Tg PS, Toxoplasma gondii-positive sera; Eg PS, Echinococcus granulosus-positive sera.

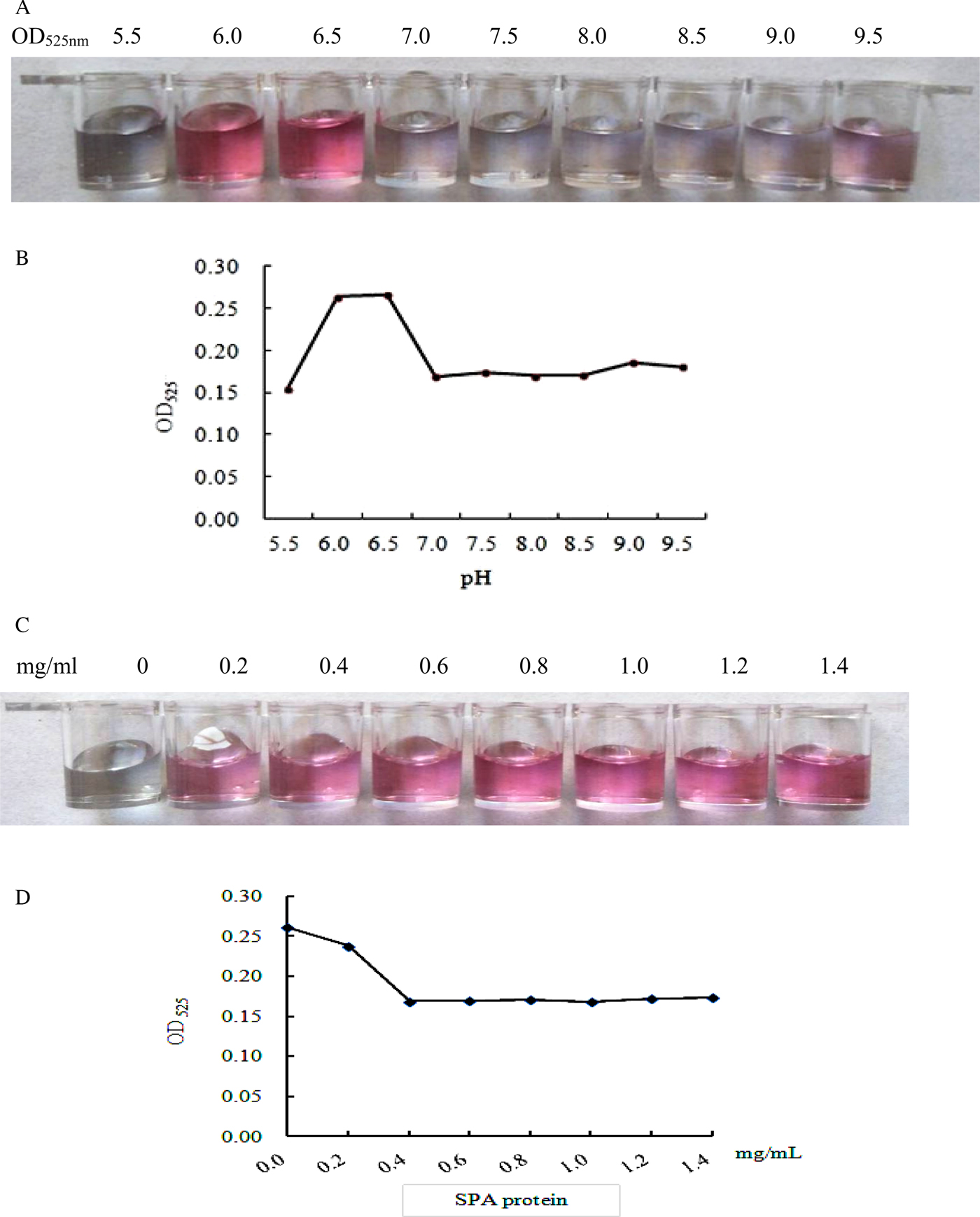

The optical density (OD525nm) of colloidal gold solution was determined, and pH 6.5 was considered as the optimum pH of colloidal gold solution (fig. 3a, b). When the labelling amount of SPA protein was 0.6 mg/ml, the colour and OD525nm value of the solution remained stable (fig. 3c, d). Thus, the actual labelling amount of SPA protein was increased by 20% (0.7 mg/ml) on the basis of the concentration. Likewise, 1 mg/ml rCatL1D protein (T-line) and 1.2 mg/ml sheep IgG (C-line) were determined as the optimal concentration coated on the NC membrane, respectively.

Fig. 3. Determination of the optimal pH and concentration of SPA-protein-labelled colloidal gold solution. (A) Observation of the colour of colloidal gold solution at different pH values; (B) determination of optical density (OD525nm) of colloidal gold solution at different pH values; (C) colour change of colloidal gold solution labelled with different SPA concentrations; (D) determination of optical density (OD525) of colloidal gold solution at different SPA concentrations.

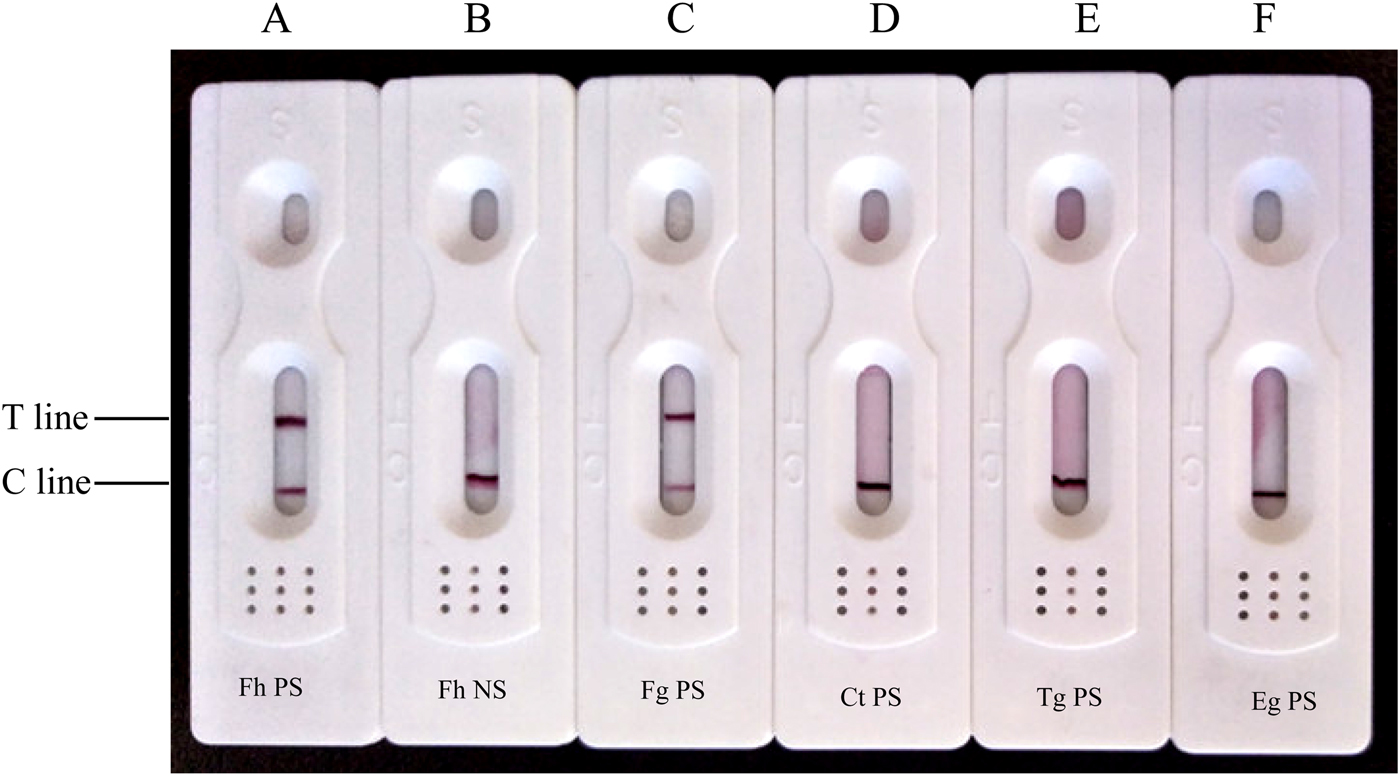

Of the tested sera, 35 F. hepatica-positive serum samples were all positive by CGIA, while ten F. hepatica-negative serum samples and five each of Eg-, Ct- and Tg-positive serum samples were all negative (fig. 4). However, Fg-positive sera were positive by CGIA. The results revealed that the rCatL1D protein exhibited good performance in the detection of Fg sera, but the cross-reaction occured with Fg positive sera.

Fig. 4. Evaluation of the performance of the CGIA test strip. (A) Fh PS (Fasciola hepatica-positive sera); (B) Fh NS (F. hepatica-negative sera); (C) Fg PS (F. gigantica-positive sera); (D) Ct PS (Cysticercus tenuicollis-positive sera); (E) Tg PS (Toxoplasma gondii-positive sera); (F) Eg PS (Echinococcus granulosus-positive sera).

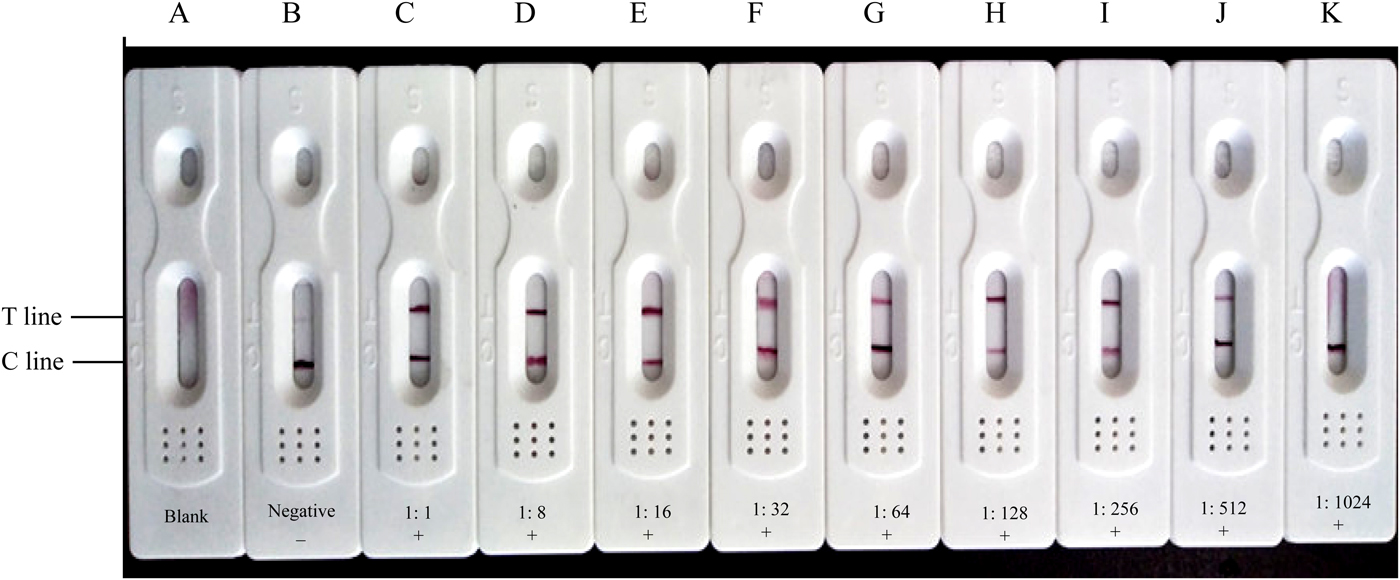

When 35 F. hepatica-positive serum were diluted to 1:512, the T-line and C-line were all coloured (fig. 5). When diluted to 1:1024, only the C-line was coloured. When examining ten F. hepatica-negative serum using the CGIA test strip, only the C-line was coloured, while the T-line and the C-line did not develop colour when the 0.2 mol/l PBS was detected, indicating that the established CGIA test displayed good performances in the detection of specific antibodies against F. hepatica.

Fig. 5. CGIA test strip for the detection of antibodies against Fasciola hepatica in sheep sera. (A) 0.2 mol/l PBS (pH 7.5); (B) Fasciola hepatica-negative serum (diluted at 1:16). (C)–(K): Fasciola hepatica-positive sera were diluted with 0.2 mol/l PBS (pH 7.5) at ratios from 1:1 to 1:1024, respectively.

Of 426 clinical serum samples, 97 samples were CGIA-positive, while 329 samples were negative. Compared with the post-mortem inspection method, the specificity and sensitivity of the CGIA method were 100% and 97%, respectively. Accordingly, the consistency rate of the two detection methods was 99.3% (table 2).

Table 2. Evaluation of the specificity and sensitivity of CGIA for the diagnosis of Fasciola hepatica infection in sheep.

Discussion

In recent years, many studies on F. hepatica ESPs have been carried out (Castro et al., Reference Castro, Freyre and Hernández2000; Molina-Hernández et al., Reference Molina-Hernández, Mulcahy and Pérez2015), which demonstrated that ESPs were one of essential class of proteases and played important roles in F. hepatica infection, migration and parasitism (Piedrafita et al., Reference Piedrafita, Parsons and Sandeman2001; Moreau et al., Reference Moreau, Hervé and Yu2002; Shrifi et al., Reference Shrifi, Farahnak and Golestani2014). Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Menon and Donnelly2009) analysed the protein components of F. hepatica adults, metacercariae and cercariae ESPs. The results showed that 13 secreted proteins in adult ESPs belonged to CatL. Among them, seven CatL and one CatB were secreted by metacercariae, while 14 proteins in cercariae ESPs belonged to CatL, indicating that Cat is more secreted in F. hepatica ESPs, presenting in various stages of F. hepatica's life cycle, and has strong immunogenicity and antigenicity. CatL can decompose proteins in the blood of the host and break down immunoglobulins (Meemon et al., Reference Meemon and Sobhon2015; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Hsu and Chastain2016), and inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines (Abdolahi Khabisi et al., Reference Abdolahi Khabisi, Sarkari and Moshfe2017). CatB is mainly present on the surface of cercariae and metacercariae (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Kong and Joo1995; Salimi-Bejestani et al., Reference Salimi-Bejestani, McGarry and Felstead2005), which is involved in the process of excystation and damages the host's immune system to achieve evasion (McGonigle et al., Reference McGonigle, Mousley and Marks2008; Jayaraj et al., Reference Jayaraj, Piedrafita and Dynon2009).

Current studies have shown that ESPs are a class of highly reactive and immunogenic F. hepatica antigenic proteins, with potential value as a candidate antigen for F. hepatica serological diagnosis (Shin et al., Reference Shin, Hsu and Chastain2016; Aguayo et al., Reference Aguayo, Valdes and Espino2018). Abdolahi Khabisi et al. (Reference Abdolahi Khabisi, Sarkari and Moshfe2017) developed a sandwich ELISA using F. hepatica ESPs as antigen to examine faecal samples from infected animals. Salimi-Bejestani et al. (Reference Salimi-Bejestani, McGarry and Felstead2005) established an indirect ELISA method using F. hepatica ESPs to detect F. hepatica antibody in cattle serum two weeks after the infection. The sensitivity of developed ELISA was high; however, the specificity was not ideal (George et al., Reference George, Vanhoff and Baker2017). Although the serological detection method based on F. hepatica ESPs exhibits high sensitivity, the ESP antigen is difficult to prepare in large quantities due to the limited number of worms. Meanwhile, due to the complex composition of ESPs, currently no standard preparation process is available. Also, the antigenicity of ESPs is highly viable among batches, which significantly affects the specificity, sensitivity and accuracy of the tests. In contrast, recombinant antigens have the advantages of large-scale preparation, standardized purification processes and stable reactogenicity (Mirzadeh et al., Reference Mirzadeh, Valadkhani and Yoosefy2017; Mokhtarian et al., Reference Mokhtarian, Meamar and Khoshmirsafa2018). Thus, this method shows great potential in the design and development of F. hepatica diagnostic antigens. Therefore, in this study, the recombinant proteins rCatL1D, rCatB4 and rMeCatL-B were prepared. Western blot and ELISA were performed using these recombinant proteins as antigens. The results confirmed that rCatL1D protein had higher sensitivity and specificity, and exclusively interacted with Fg-positive serum. These properties allow the rCatL1D protein to be used as a candidate diagnostic antigen for detecting F. hepatica-specific antibodies.

CGIA is a novel detection method that combines immunological detection methods with chromatography and colloidal gold labelling (Kong et al., Reference Kong, Yang and Gong2017; Yu et al., Reference Yu, Ouh and Kang2018). Staphylococcus aureus protein A (SPA) can specifically bind to Fc fragments of IgG in various mammalian serum, and SPA shows strong affinity to IgG. Therefore, SPA-labelled colloidal gold was used to develop the CGIA method to detect sheep serum samples. Compared with the post-mortem inspection, the CGIA method displayed higher specificity and sensitivity, and the consistency rate of the two methods was 99.3%. These results revealed that the CGIA established in this study could serve as a promising method for the rapid diagnosis of sheep fasciolosis.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X19000919.

Acknowledgement

We thank the field staff who provided the technical assistance for this study.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (grant number 2017YFD0501200), the International Science and Technology Cooperation Program of XPCC (grant number 2016AH006) and the Xinjiang Autonomous Region graduate innovation project (grant number XJGRI2014059).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines issued by the Ethical Committee of Shihezi University, Xinjiang, China.