Is there something really specific about our contemporary globalization? In other words, what is now framed as global that was not before? This is one main issue that we face in the social sciences when attempting to make sense of such notions. If globalization is a new phenomenon, what does it comprehend, and why are the social sciences better equipped to analyse it? To answer those questions, we must first try to qualify what we mean by ‘global’ and ‘globalization’.

One prominent feature is the very recent use of those terms. The first article said to have introduced the notion of globalization, ‘The globalization of markets’, was published in the Harvard Business Review in 1983.Footnote 1 It focused on the worldwide homogenization of consumption habits, on the growing convergence towards a single global market, and on the rise of transnational companies with a global marketing strategy. In the decade that followed, ‘global’ and ‘globalization’ were closely tied to the launch of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the multiplication of international trade agreements, increasing economic integration within the European single market, and the opening of many countries to international trade, especially ‘emerging’ countries from eastern Europe, East and South Asia, and South America. In that sense, globalization referred to the rise of global trade. Indeed, according to the WTO, the share of exports increased from 10% of global GDP in 1970 to 20% in 1990 and 30% in 2010. In addition, global trade had grown much faster (7.2% per year between 1950 and 1980) than global GDP (4.7% per year over the same period).Footnote 2

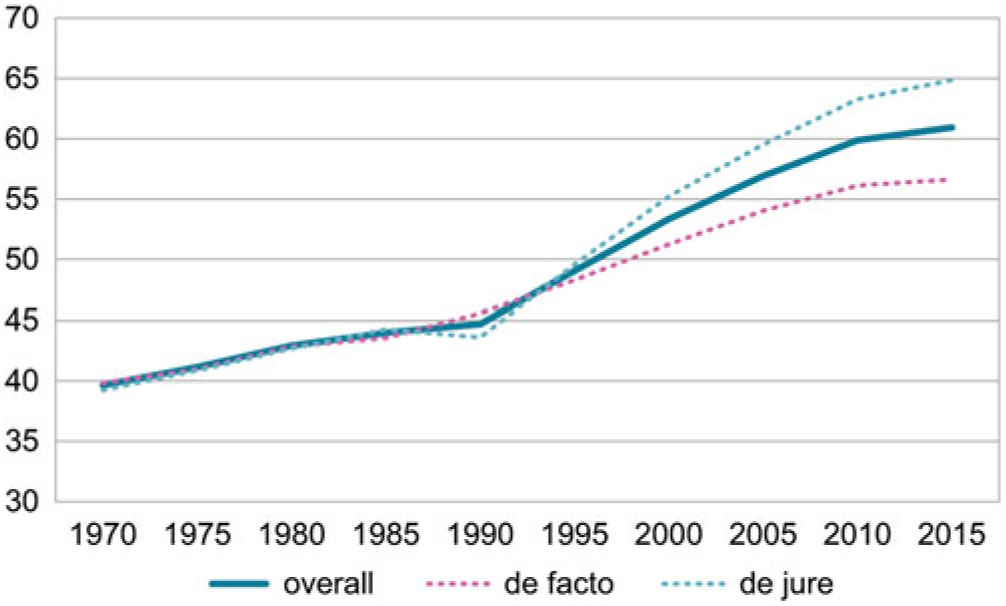

However, reducing globalization to the increase in global trade remains problematic, as many social scientists have repeatedly demonstrated. They prefer to speak of ‘waves of globalization’ or of an integrated ‘world system’.Footnote 3 Measuring the openness to global trade from the beginning of the nineteenth century, Christopher Chase-Dunn, Yukio Kawano, and Benjamin Brewer show that the ‘average openness to trade globalization’ index that they calculated, once weighted by the number of existing countries, indicates the existence of at least three waves: at the end of the nineteenth century, between the two world wars, and at the end of the twentieth century (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Average openness to trade globalization (1815–1995). Source: Christopher Chase-Dunn, Yukio Kawano, and Benjamin D. Brewer, ‘Trade globalization since 1795: waves of integration in the world-system’, American Sociological Review, 65, 1, 2000, p. 85.

The very notion of ‘waves’ of globalization supported the sceptics’ thesis that globalization is just a myth. According to them, the internationalization of the economy is not recent, but has historical precedents. For example, they argue that transnational corporations, which are supposed to embody contemporary globalization, are neither new nor particularly numerous. They assert that globalized capital remains concentrated in developed countries, as well as the bulk of trade, investment, and financial flows, as it was before. And they believe that markets that are supposedly free of state control actually continue to be regulated and controlled by states.Footnote 4

However, this thesis can be challenged by bibliometric studies that show how the terms ‘global’ and ‘globalization’, almost non-existent in the scientific literature before 1980, have since experienced an explosion in the social sciences, and in particular in sociology, economics, and political science. Book titles demonstrate that words beginning with ‘globali-’, such as ‘globalisation’, ‘globalization’, ‘globalised’, and ‘globalized’, hardly mentioned in 1980, were present in about 500 books in 1990, in more than 1,000 in 2000, and in around 1,500 in 2005, as referenced in the Library of Congress and WorldCat catalogues.Footnote 5 Moreover, when analysing the way in which the different disciplines of the social sciences have taken an interest in the phenomenon, we observe that historians have not shown a particular interest in studying globalization. In fact, along with economics, ‘sociology was the first to pay attention to globalization’, with a peak at the end of the 1990s, while ‘the historical and anthropological literatures, by contrast, have lagged behind’.Footnote 6 Sociological abstracts mentioning ‘global’ in their titles went from almost zero in the mid 1980s to more than 200 per year at the beginning of the twenty-first century.Footnote 7 Indeed, a third of the articles mentioning globalization come from just four disciplines: economics (8%), geography (7%), sociology (7%), and political science (6%).Footnote 8 While historians (and anthropologists) often diminish the novelty of transnational flows and exchanges, and assimilate them to those of the past, many social scientists, and sociologists in particular, have instead looked for something specific and new in the current wave of globalization.

Accordingly, I believe that our current globalization cannot be reduced to trade and financial flows, or to converging markets across the world. It is actually more complex than simply an increase in international trade, and it is developing in several dimensions. I defend the thesis that the terms ‘global’ and ‘globalization’ have served to identify a qualitatively new phenomenon. In this article, based on previous publications, I therefore turn first to the novelty of the discourse on globalization.Footnote 9 Several of the dimensions associated with globalization are then examined in more detail to understand what is actually specific to them: migration, world trade, finance, stratification, and global culture.

The trajectory of the terms ‘global’ and ‘globalization’ in sociology

Sociology articles published in US journals and mentioning the term ‘global’ between 1985 and 2003 increased from 20 per year in 1990 to more than 200 in 2002.Footnote 10 This rise of the notion of globalization in sociology and social sciences is also demonstrated by the founding of dedicated journals: Globalizations in 2004 and Global Networks in 2001. Another sign of the institutionalization of the notion is the new section ‘Global and transnational sociology’ launched in 2008 within the American Association of Sociology.

This surge is quite astonishing, given the quasi-absence of the term ‘global’ in the sociological tradition. Indeed, the ascent of sociology as a discipline, like many other social sciences, has been intertwined with the building of nation-states. Sociologists dedicated themselves to the study of national societies, and when the founding fathers of sociology, such as Weber or Durkheim, demonstrated an interest in international issues, they emphasized the international comparison between national societies. Durkheim, for example, envisioned comparisons as a privileged instrument for causal inference in sociology.Footnote 11 He put them to use to compare suicide rates in various European societies at the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 12

Only one of the founding fathers of the discipline – Marx – analysed a socioeconomic phenomenon that looks very similar to our contemporary globalization: the global expansion of capitalism. In his Manifesto of the Communist Party, he even used the term ‘globe’. Quoting the relevant passage at length will allow us to better analyse what distinguishes contemporary globalization from the one that Marx observed in the nineteenth century:

The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the entire surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere. The bourgeoisie has through its exploitation of the world market given a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country. To the great chagrin of Reactionists, it has drawn from under the feet of industry the national ground on which it stood. All old-established national industries have been destroyed or are daily being destroyed. They are dislodged by new industries, whose introduction becomes a life and death question for all civilised nations, by industries that no longer work up indigenous raw material, but raw material drawn from the remotest zones; industries whose products are consumed, not only at home, but in every quarter of the globe. In place of the old wants, satisfied by the production of the country, we find new wants, requiring for their satisfaction the products of distant lands and climes. In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal inter-dependence of nations. And as in material, so also in intellectual production.Footnote 13

In Marx’s analysis of the expansion of capitalism in the middle of the nineteenth century, I recognize many of the elements defining the process of contemporary globalization. First, it has economic features: the global expansion of capitalism, the growth of international trade, the dispersion of production, the generalization of foreign investment, and increasing the economic interdependence between nations. Second, this economic process goes hand in hand with technological changes, in particular in the information and communication domains, and therefore has cultural properties: the homogenization of consumer needs on a global scale, and the emergence of a universal culture. Third, it has a social underpinning, since it promotes the rise of a global and mobile bourgeoisie, while increasing and reinforcing world inequalities. This long quotation also has the advantage of showing us that, in Marx’s opinion, globalization is not a phenomenon that can be reduced to economics and economic analysis. On the contrary, it is a phenomenon with social dimensions, in particular socioeconomic, sociopolitical and sociocultural ones, which a sociological perspective is best able to capture.

Above all, a comparison between this passage and the definitions of contemporary globalization gives Marx’s text an interestingly prophetic character. Indeed, the current discourses on contemporary globalization stress the thesis of global market integration, with self-regulating markets, and depict it as an irreversible and inevitable economic mechanism that increases global inequalities and diminishes states’ leverage.Footnote 14 Widespread definitions of our contemporary globalization emphasize the convergence towards a single global market.

According to Neil Fligstein, for example, globalization refers to deindustrialization and growing inequalities. It serves to justify the inaction of governments, which are said to be trapped between an increased demand for public services, because of rising unemployment and diminishing wages, and their growing inability to use fiscal instruments (so as not to discourage foreign investment) or to borrow money (so as not to risk the decline of their national currency on international financial markets). For Fligstein, the notion of globalization serves to justify increasing inequalities, precariousness, and reduced access to public goods such as health and education. Moreover, it helps to diminish government intervention, and promotes neoliberal policies.Footnote 15 In France, Frédéric Lebaron has defended a similar thesis: the discourse on globalization simply justifies market capitalism, deregulation, tax cuts, and reductions of state expenditure. Based on common-sense reasoning, rather than on scientific arguments, it is especially promoted by economists and politicians, who benefit from this discourse: ‘It is the social space situated at the intersection of the dominant factions of these two groups that plays a part in the current process of globalization.’Footnote 16

The study of the social trajectory supports the thesis that the notions of ‘global’ and ‘globalization’ themselves stem from the financial sector. Two US scholars, Peer Fiss and Paul Hirsch, have documented the emergence of the term ‘globalization’ in US newspaper articles and companies’ press kits over three decades, starting from the 1980s. In the newspapers, the term ‘globalization’ first appeared in the 1980s. Between 1985 and 1987, 5% of articles mentioned it. References then plateaued, before rising again to 20% after 1995. According to the authors, such fluctuations can be explained by the deregulation of financial markets in the 1980s, which favoured the rise of the term ‘global’, then by the stock market crash of 1987, which interrupted the process, and eventually by the creation of the WTO in 1995, which re-launched the term in publications. It must be added that, from 1984 to 1987, 75% of the articles mentioning the notion of globalization belonged to the finance section. However, they represented only 25% of the total between 1995 and 1998. The term globalization had thus spread from the finance section to the other parts of the newspapers.

The trend has been similar in companies’ press kits. Fiss and Hirsh indicate that, from 1984 to 1987, half of the companies that mention ‘globalization’ were part of the financial sector. Their share dropped to 25% after 1995, as other companies from the industrial, technological, and consumer goods sectors began to use the word. Moreover, while press kits and articles were relatively neutral at the beginning of the period, their coverage became more and more positive over time. Conversely, newspaper articles’ coverage became more and more negative.Footnote 17

These findings support the idea that the terms ‘global’ and ‘globalization’ came from the financial sector in the early 1980s, to describe how capital was internationalized in that period. The terms were also performative, insofar as they were used to justify globalization strategies by transnational corporations, and to encourage investments abroad. A few advertisements from transnational companies in the 1990s are indeed telling. ‘The world is our audience’, claimed Time Warner. Sony launched ‘Think globally, act locally’. In the early 2000s, HSBC boasted of being ‘the world’s local bank’. Therefore, the social trajectory of ‘global’ and ‘globalization’ provides some support for an argument that these terms spread a liberal rhetoric from the financial and business worlds, which became a threat to the very foundations of the welfare state.

Subsequently, the notions of ‘global’ and ‘globalization’ have become popular and are now used to describe many other dimensions of transnational exchanges, flows, and circulations.

Coming back to Marx’s stance on the global extension of capitalism, we can identify other classic definitions of our contemporary globalization that resonate with Marx’s intuitions, and add to the solely economic dimension. For example, Susan Strange underlines three major changes in international relations in association with globalization, which point to the technological and communication sectors, as much as to the economy. She does stress ‘increased capital mobility, which has made this dispersion of industry easier and speedier’. But she also emphasizes the ‘accelerating rate and cost of technological change, which has speeded up in its turn the internationalization of production, and the dispersion of manufacturing industry to newly industrialized countries’. Finally, she identifies ‘changes in the structure of knowledge that have made transnational communications cheap and fast and have raised people’s awareness of the potential for material betterment in a market economy’.Footnote 18 On a similar note, when the journalist Thomas Friedman summarized the main properties of contemporary globalization, he defended the thesis of an increasingly ‘flat world’ in connection to economic changes, such as the rise of global supply circuits, but also in relation to technological changes, such as the internet, the rise of web 2.0, and instant messaging, and even to geopolitical events, such as the fall of the Berlin Wall. Overall, they fit with the global dominance of the market economy model.Footnote 19

Yet many sociologists have stressed the novelty of the globalization phenomenon. In fact, the most famous sociological theories of globalization, which were developed in the 1990s by Saskia Sassen and Arjun Appadurai, emphasized this feature of our contemporary globalization. Sassen and Appadurai are the most frequently cited authors on the issue, along with international organizations such as the World Bank, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the UN.Footnote 20 In various respects, their theories defend the thesis of a new global era. In addition, Manuel Castells speaks of the birth of an informational capitalism and a new network society. Sassen evokes an era engaging ‘two key assumptions in the social sciences’: that the nation-state would no longer be the container of social processes, and that there would be no obvious correspondence of national territory with what is defined as national.

Sociology has also assimilated some authors categorized as anthropologists, such as Appadurai, who evokes new transnational landscapes replacing the traditional geography of national territories. His work was very quickly combined with Castells’ and Sassen’s perspectives. Likewise, George Marcus’ anthropological conception of a multi-sited ethnographical fieldwork has been influential in qualitative and fieldwork sociology. With new issues emerging, such as transnational media and communication, epidemics, and environmental studies, Marcus argues that ethnographers should now try to follow people, objects, metaphors, stories, or conflicts on a transnational basis, rather than limiting their fieldwork to a single site.Footnote 21 Sociologists have subsequently taken up such an approach, when identifying relevant issues for a ‘global ethnography’, including global flows and circuits, transnational phenomena such as migrant round trips, border practices, global policies, global forces of capitalism or neoliberalism, and global connections.Footnote 22

The term ‘globalization’ has thus come to encompass a series of phenomena that go far beyond opening up to international trade alone, and refer to both quantitative and qualitative changes in the way that international exchanges and flows are conducted and affect societies worldwide. This complexity of the phenomenon is reflected in the structure of the ‘KOF’ index of globalization developed by the Polytechnic University of Lausanne, which is based on three broad sets of indicators. The first refers to ‘participation in economic globalization’ and combines two types of indicators: those relating to participation in international trade, through the measurement of trade flows; and those relating to international financial flows. But the two other dimensions cover ‘participation in social globalization’ and ‘participation in a political dimension’. More specifically, the second one includes measures of tourist and migrant flows, international communications, and interpersonal contacts. It also adds indicators on information flows, such as the number of patents or international students, and trade flows of new technologies, or access to information, such as the rate of access to the internet and the level of press freedom. It also covers cultural globalization, measuring the circulation of cultural goods, the presence of multinationals (including international brands, such as the number of branches of McDonald’s and IKEA), and the ability to participate in cultural exchanges, such as the level of individual freedoms, gender equality, and education spending. Finally, the third dimension, focusing on political participation, measures participation in multilateral cooperation and transnational networks, determined by the number of embassies and NGOs in the country, participation in UN peace missions, adhesion to international organizations, and the signing of international treaties.

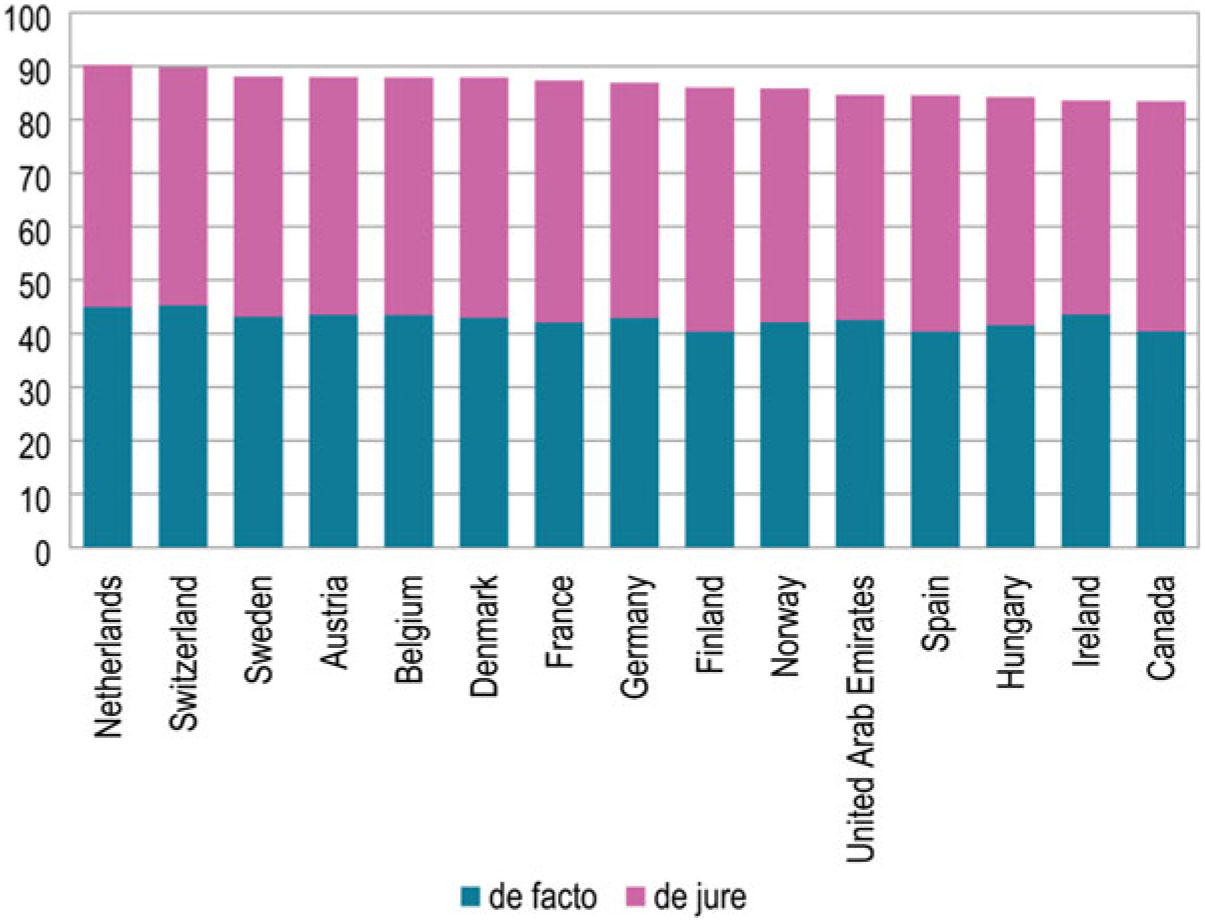

This index allows two significant observations to be made. First, there has been a steady increase in all the measures between 1970 and 2015, with a marked surge starting from 1990. This signals an even faster growth than in the earlier period, and demonstrates an increasing globalization over the past thirty years (see figure 2). Second, the countries that participate most in the different dimensions of globalization (as measured by the KOF index) are first and foremost small countries, particularly European countries, such as The Netherlands, Switzerland, Sweden, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, and Norway, but also the United Arab Emirates and Singapore. Other European countries such as France, Germany, Ireland, Spain, and Hungary are also very well placed. While Canada is among the top fifteen countries participating in globalization, the United States is not, nor are other countries that are considered emblematic of contemporary globalization, such as Japan and China (see figure 3).

Figure 2. KOF Globalisation Index, world average (%). Source: KOF Swiss Economic Institute. The difference between the ‘de facto’ and ‘de jure’ lines can be explained by the choice of indicators which, in the first case, refers to the measurement of actual movements (persons, goods, services) and, in the second, to the measurement of the capacity to participate in exchanges (level of individual freedoms, access to information, mobility, etc.). It should be noted that ‘de jure’ globalization has accelerated even faster over the past thirty years than ‘de facto’ globalization.

Figure 3. KOF Globalisation Index, top fifteen countries, 2015 (%). Source: KOF Swiss Economic Institute.

Now that we have highlighted the social complexity characterizing globalization, let us analyse the nature of the social changes that it engages in some of the sectors that have been scrutinized in sociology and the social sciences: migrations, finance, trade, and culture.

Migrations: from migrants to transmigrants

Contemporary globalization has been associated with the mobility of people. On this point, it may be noted that the number of air passengers has increased very steadily from 1975 to 2015, from 500 million to 4 billion, according to World Bank figures. International migrations also seem to have increased greatly, according to UN figures, from 75 million migrants in 1960 to 177 million in 2000, and 258 million in 2017. However, these figures should be compared with world population, which has also risen very sharply over the same period. Indeed, the percentage of international migrants has increased less rapidly than the absolute numbers would let us think, rising only from 2.5% to 3.5% of the world population between 1960 and 2017.

On the other hand, it can be said that international migration has not waited for contemporary globalization. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there were three major waves of international migration. One is well known: almost 60 million European migrants, first from northern Europe and then from southern Europe, left for the Americas, with very high emigration rates in some Irish or Italian villages, and a peak in emigration at the very beginning of the twentieth century. But there were also very important migrations in Southeast Asia (50 million migrants), and to Central Asia and Siberia (50 million), over the same period.Footnote 23

So what is so specific about the migration of contemporary globalization? In my opinion, the answer lies in the sociology and socio-anthropology of migration, which have been increasingly attentive to ties that persist for migrants between their home and host countries, such as repeated round trips, daily communications, and increasing remittances. This led a group of researchers to coin the term ‘transmigrant’ in the early 1990s, to replace ‘immigrant’, ‘emigrant’, and ‘migrant’. Transmigrants are defined as immigrants whose daily lives depend on multiple and constant cross-border interconnections, and whose public identities are shaped in relation to more than one nation-state.Footnote 24 Between the two communities to which transmigrants belong, many remittances can take place; these can be monetary, but they can also be ‘social remittances’, such as ideas, modes, information, practices, and contacts. These may be significant enough that we can talk about ‘transnational villagers’.Footnote 25 The notion of transnationalism has been constructed to contrast with a ‘methodological nationalism’ generally applied to the study of international migrations,Footnote 26 even though states retain a key role for migrants by regulating travels and remittances.Footnote 27 According to World Bank figures, the amount of monetary remittances increased from about US$30 billion in 1990 to more than US$200 billion in 2005, exceeding by far the amount of international aid, which was only half as much at that time. In fact, what really characterizes these transnational migrants is that they can participate in two social, political, family, and cultural contexts at the same time, to be there and here simultaneously. Clearly, migrants from earlier waves of globalization maintained many contacts with their home region, but they could not keep such regular, multidimensional, and intense ones. It is therefore this transnationalism that seems specific to contemporary globalization.

Trade: commodities, logistics, and the WTO

International trade is also emblematic of contemporary globalization. Carefully scrutinizing the moment when the use of the term ‘globalization’ took off in common usage allows us to identify a turning point in 1995. This year saw the creation of the WTO, whose mission is to remove tariffs and other barriers to international trade. However, the same question can be asked as for contemporary migration: how is international trade specific to contemporary globalization? Let us remember Marx’s text, which in the nineteenth century observed the invasion of the globe by the capitalist bourgeoisie seeking ever more distant outlets and markets for its products. And, indeed, previous waves of globalization saw a strong expansion of international trade, with two distinctive peaks, in the 1860s and the 1910s.Footnote 28

Nevertheless, as I have done for migrations, I would like to look at what is specific to contemporary international trade, and how a sociological perspective can analyse this. Many features distinguish international trade in our contemporary globalization. First, manufactured goods now account for more than half of international trade, while agriculture and raw materials were still dominant in the nineteenth century.Footnote 29 Half of international trade is also nowadays handled within ‘global value chains’, and through a complex network of global subcontracting ties. This has been made possible by decreasing transportation costs, as the emblematic case of the textile industry shows.Footnote 30 Meanwhile, as we saw in the introduction, international trade has expanded exponentially in the past forty years. Trade in commodities quadrupled to US$19 trillion between 1980 and 2014, and trade in services increased tenfold to US$4 trillion in the same period.Footnote 31 Sociologists have not neglected these new aspects of globalization, and have studied, for example, the rise of logistics in contemporary international trade and its consequences for global politics.Footnote 32

Second, international trade in the nineteenth century was a component of imperial domination and colonial exploitation by Western countries, as the ‘world-system’ literature has demonstrated.Footnote 33 In our contemporary globalization, global trade remains fundamentally unequal, because it inherits from these past power relations, explaining the late development of ‘Third World’ countries and the adverse effects that many experienced when they opened up their economies to free trade. But our contemporary globalization is also characterized by the rise of ‘emerging’ countries in international trade. Thus, the share of ‘developed’ countries (the European Union, the United States, Canada, and Japan) in the international exchange of commodities decreased from 66% in 1980 to 53% in 2011. Conversely, that of China rose from 1% to 11%. In addition, the share of ‘North–North’ trade fell from 56% in 1990 to 36% in 2011, while the share of ‘South–South’ trade increased from 8% to 24%.

Sociologists have been working on this second and new dimension of international trade. For example, Amy Quark and Adam Slez have recently studied the evolution of the balance of power in international trade. They have shown how US cotton subsidies ensured the hegemony of the United States vis-à-vis ‘emerging’ countries specializing in the textile industry throughout the twentieth century. But they also show, relying on a network analysis, how, in the past two decades, the US has increasingly relied on China, which has become their main importer, and handles most of the current garment business in the world. The direction of the balance of power is now much less clear between ‘developed’ and ‘emerging’ countries, since both are completely dependent on the exports and imports of their main partner.Footnote 34

Third, international trade seems to be much more resilient to crises than it was in the twentieth century, when the two world wars and the 1929 crisis all crushed it. In fact, in 1938, the value of world trade still represented less than half of that in 1928.Footnote 35 The 1930s depression, like that of the 1870s, led to a sharp rise in tariffs. Today, the average of such tariffs does not exceed 5%, and most trade restrictions are now technical, sanitary, environmental, or meant to protect consumers. Thus, after the 2008 crisis, world commodities exports certainly experienced a recession, falling by 12% when compared with a 2% decline in world GDP, but trade growth was back to 14% in 2010, versus 4% growth for world GDP.

On these points, sociologists have taken a particular interest in the institutions of contemporary international trade. In the nineteenth century, free trade was essentially promoted by Britain, and then by a series of trade agreements modelled on the Anglo-British treaty of Cobden-Chevalier of 1860. But at the end of the twentieth century, free trade relied on multilateral institutions that allowed for a growing global consensus.Footnote 36 Sociologists have shown how a wide range of elite actors mobilized around such agreements, including ‘technocrats’, economists, and ‘businesspeople’.Footnote 37 The creation of the WTO in 1995 is a testament to this growing institutionalization of international trade.Footnote 38

Sociologists have also focused on the way in which social movements have targeted international trade agreements. For example, they have studied how ecological movements have pushed to include environmental issues in the negotiations over NAFTA.Footnote 39 NAFTA actually weakened the rights of workers in the United States, but paradoxically pushed the Mexican, US, and Canadian unions to join forces, triggering later mobilization against trade agreements.Footnote 40 Increasing demand for trade regulation has emerged, as certifications intended to circumvent the exotic wood trade or the use of child labour in the textile industry, or to label organic farming, have shown.Footnote 41

In contemporary globalization, international trade is therefore very specific. It is a trade in goods, based on value chains, logistics, and the standardized shipping container invented in the 1960s. It is a more global trade, in which certain ‘emerging’ countries find their place in a balance of power with Western countries that is not only no longer imperial but also increasingly rebalanced, as shown by China’s symptomatic case. And it is a much more institutionalized trade, regulated by international and multilateral institutions, foremost among them the WTO. Sociologists have worked on these three dimensions, showing that this international trade has little to do with previous waves of globalization.

Finance: global cities and informational capitalism

Above all, transnational finance has been seen as symptomatic of contemporary globalization. However, we face the same problem as before: previous waves of globalization were similarly characterized by transnational capital flows, like foreign investments, and the rise of global stock exchanges, such as the London Stock Exchange in the nineteenth century. So what is new for transnational finance in our current globalization? An answer to this question can be found in the major sociological theories of globalization, which place transnational capital flows at the heart of their arguments. Two sociologists in particular, Saskia Sassen and Manuel Castells, have explored the changes relevant to transnational finance in recent decades.

Financial flows are at the heart of Sassen’s thinking. The three ‘global cities’ on which she focused in what is now considered a classic and crucial book on globalization, The global city, published in 1991, are in fact three financial capitals: London, Tokyo, and New York.Footnote 42 To Sassen, what is radically new in our current globalization is the degree to which the technological changes in transportation and telecommunication have polarized global economic activity. Indeed, while production has increasingly been dispersed around the globe, and has spread across commodity chains, there has been an extreme concentration of the functions of management, coordination, consulting, law, and, above all, financing, to manage such a complex dispersion. Global cities are the sites where these functions are regrouped, and where financial capital is amassed to serve this increasingly dispersed and global production.

In addition, global cities are intrinsically linked to each other, in contrast to world cities, which have always existed but were not directly networked and coordinated with each other. In particular, Sassen sees finance as the core coordinating mechanism of the entire global economy. She argues that, in our current globalization, global cities are interlinked through financial flows, and stock exchanges are synchronized to each other, sharing information in less than milliseconds. Therefore, global cities are part of one and the same globalized system, explaining why Sassen chose a singular noun – ‘the global city’ – as the title for her book. This helps us to understand why global cities seem more and more connected to other global cities, while being less and less tied to their national hinterland, in contrast to world cities that oversaw regions, countries, or empires in the past. This network of global cities now forms the infrastructure of globalization, explaining why transnational corporations settle in such cities to benefit from a transnational network.

Sassen also links international migration to the international mobility of capital, and explains that they are mutually constitutive. To her, global cities are increasingly polarized between two groups. The first is made up of hyper-skilled individuals with high incomes and high levels of education controlling economic activity and managing the world economy on a global scale. The other group includes unskilled individuals, mostly immigrants from poor countries, who are low-paid, unprotected, and uninsured, and who are employed in menial jobs, mostly in the services sector – cleaning agents, waiters, guards, drivers, security agents – or are part of survival economies within immigrant communities.Footnote 43

Castells’ reflection is similarly partly organized around international finance, which he believes is the ‘backbone’ of the changes he observes in capitalism, and which has been entirely transformed by the ability to transmit financial information almost instantaneously anywhere in the world. In The rise of the network society, published in 1996 as the first of three volumes on the ‘information age’, he therefore developed several concepts that have since flourished: informational capitalism, network society, space of flows.Footnote 44 His starting point is the revolution in information technologies, which he traces back to turning points such as the invention of the transistor, or the shift of the microelectronics sector from the east coast to the west coast of the US, and the creation of Silicon Valley. This revolution, based on new information technologies, information literacy, organizational flexibility, and financial innovations and networks, has reshaped modern capitalism. To put it in Castells’ words:

A new economy emerged in the last quarter of the twentieth century on a worldwide scale. I call it informational, global, and networked to identify its fundamental distinctive features and to emphasize their intertwining. It is informational because the productivity and competitiveness of units or agents in this economy (be it firms, regions, or nations) fundamentally depend upon their capacity to generate, process, and apply efficiently knowledge-based information. It is global because the core activities of production, consumption, and circulation, as well as their components (capital, labor, raw materials, management, information, technology, markets) are organized on a global scale, either directly or through a network of linkages between economic agents. It is networked because, under the new historical conditions, productivity is generated through and competition is played out in a global network of interaction between business networks. This new economy emerged in the last quarter of the twentieth century because the information technology revolution provided the indispensable, material basis for its creation. It is the historical linkage between the knowledge-information base of the economy, its global reach, its network-based organizational form, and the information technology revolution that has given birth to a new, distinctive economic system.Footnote 45

Several factors have combined to implement such an information economy: the transition from a mass production regime (Fordism) to a more flexible production regime with the diffusion of the model of networked companies; the transformation of work and employment, with a greater emphasis on individuals and flexibility, coupled with the weakening of protective institutions; a new culture stemming from the use of television, satellites, and the internet; the internationalization of financial investments; the international fragmentation of production; and the reproduction of the North/South divide in terms of access to knowledge. In this new economy depicted by Castells, competition is based on the ability to produce and manage knowledge.

Castells also insists on the political dimension of this informational capitalism:

While capitalism is characterized by its relentless expansion, always trying to overcome limits of time and space, it was only in the late twentieth century that the world economy was able to become truly global on the basis of the new infrastructure provided by information and communication technologies, and with the decisive help of deregulation and liberalization policies implemented by governments and international institutions.Footnote 46

And he stresses that this new economy is inherently unequal: experts, business leaders, technocrats, scientists, artists, and all those who make up the elite of our contemporary globalization are internationally mobile, while workers are not.

Castells eventually insists on the notion of network. To him, it is a new social morphology, which applies not only to companies but also to the state and the society that integrate networks as a whole. Networks are shaped by connected nodes. They can expand and recompose themselves without any limit. Therefore, they are fully articulated with this new informational capitalism. This has consequences in terms of the distribution of power within society: for individuals and economic units alike, the location within the network and the dynamics of each network in relation to the others have become essential. Networks are characterized both by strong asymmetries and by a certain independence from those who think that they control their nodes. They can be commercial, entrepreneurial, epistemic, cause-centred, diasporic, and so on.

Once global networks have been formed, it is impossible to disconnect from them, as:

Any node that disconnects itself is simply bypassed, and resources (capital, information, technology, goods, services, skilled labor) continue to flow in the rest of the network. Any individual decoupling from the global economy implies a staggering cost: the devastation of the economy in the short term, and the closing of access to sources of growth. Thus, within the value system of productivism/consumerism, there is no individual alternative for countries, firms, or people. … In some instances, some places may be switched off the network, their disconnection resulting in instant decline, and thus in economic, social and physical deterioration.Footnote 47

The internet is emblematic: its unity is the network, and this network has a certain geography, excluding some places and including others.

Castells thus evokes the emergence of a new space of flows, which gives shape to the network society: ‘our society is constructed around flows: flows of capital, flows of information, flows of technology, flows of organizational interaction, flows of images, sounds, and symbols. Flows are not just one element of the social organization: they are the expression of processes dominating our economic, political, and symbolic life.’Footnote 48 According to him, contemporary globalization is structured around this new space of flows imposing its dynamics to dispersed and segmented places. Flows invent sites, and therefore nodes and hubs are the new geography of globalization:

The space of flows is not placeless, although its structural logic is. … Some places are exchangers, communication hubs playing a role of coordination for the smooth interaction of all the elements integrated into the network. Other places are the nodes of the network; that is, the location of strategically important functions that build a series of locality-based activities and organizations around a key function in the network. Location in the node links up the locality with the whole network.Footnote 49

Silicon Valley, with its hundreds of thousands of experts in new technologies, is one of the most emblematic sites, but Castells also cites, for example, Rochester, Minnesota, and the Parisian suburb of Villejuif, which ‘would become central nodes of a world network of advanced medical treatment and health research, in close interaction with each other’.Footnote 50

It should be noted that these sociological theories of globalization built on the analysis of the transformations of finance and capitalism in the 1990s, and defended the thesis of radical novelty. Sassen and Castells both argued that processes once circumscribed by national territory were increasingly global and transnational, and that the leverage of national states within globalization had diminished. For the former, global cities were increasingly disconnected from their national territory, and in a later book she defended the idea that we have now moved from a national to a global era.Footnote 51 For the latter, national and territorial geography was competing with new forms of spatial organization, now centred on flows, networks, nodes, and clusters. It should also be noted that this observation is diametrically opposed to what Marx observed in the nineteenth century. He articulated the global dispersion of industries as strengthening nation-states, stating that ‘The necessary consequence of this was political centralisation. Independent, or but loosely connected provinces, with separate interests, laws, governments and systems of taxation, became lumped together into one nation, with one government, one code of laws, one national class-interest, one frontier and one customs-tariff.’Footnote 52 In a sense, the reading of our contemporary globalization by Sassen and Castells has been truly global, while Marx’s lens remained deeply national.

One might therefore deduce from Sassen’s and Castells’ reading that contemporary globalization, particularly through international finance, would go hand in hand with the disappearance of welfare states. However, many sociologists have demonstrated that global capitalism has continued to depend on national societies. Neil Fligstein, for example, recalls how ‘capitalism remains anchored in the national framework’ and emphasizes that ‘capitalist enterprises remain dependent on their respective national governments, which alone are able to provide stable political conditions, infrastructure, customs protection, trade agreements, competition policies, privileged access to the capital market and, where appropriate, direct aid’.Footnote 53 Other sociologists emphasize how multinational corporations have often been historically national ‘champions’, as in France in the case of energy or construction.Footnote 54

In the latter case, globalization actually reinforces ‘the interweaving of public and private actors in different types of legal relations (contracts, concessions) and sometimes political (financing of political life)’, and overall the passage from a ‘city government’ to ‘urban governance’, in which ‘the state loses its centrality and its (relative) monopoly in public action processes’.Footnote 55 On the other hand, we can highlight the fact that transnational corporations ‘setting out to conquer the electricity market in Côte d’Ivoire, water in Sao Paulo, the Hong Kong airport or a Malaysian toll highway … are supported by their national markets, and supported by their governments’.Footnote 56 Transnational corporations also remain constrained by domestic markets. For example, those specializing in life insurance, well established in Hong Kong, failed to gain a foothold in Taiwan, owing to competition from local state-owned companies.Footnote 57 A whole literature shows how the globalization of finance was the result of political decisions and public policies.Footnote 58

Sociologists have questioned the disappearance of the welfare state, the threat of globalization to social policies, and the weakening of the nation-state as a protective institution for working classes. For Robert Castel, for example, ‘the globalization of trade, the free movement of goods and capital, will cause this nation-state to no longer have sufficient autonomy to decide and implement its policies. Economic and social globalization would thus participate in the “crumbling of the wage society” and the “re-commodification of social protection”.’Footnote 59 Nevertheless, Castel was convinced that the nation-state would remain the main political institution able to protect the working class in the context of industrial relocation and offshoring. However, when checking the impact of a series of globalization indicators (investment, imports and exports, openness) on twenty democracies’ level of social protection between the 1970s and the 2000s, counterintuitive effects can be observed, sometimes even the opposite of those expected: the Scandinavian democracies have been increasingly opened up to international exchanges, while securing strong welfare states.Footnote 60 The effects of globalization itself might be much smaller than those of the domestic political decisions in each country.

Culture: from cultural flows to the threat of a single global culture

The issue of the globalization of culture puts the state at stake, insofar as its role was often ignored and minimized, when in fact it has remained crucial. The circulation of cultural goods, artefacts, commodities, knowledge, and ideas has long been identified and analysed by anthropologists, from well before the notions of ‘global’ and ‘globalization’ appeared. It makes a lot of sense that an anthropologist like Appadurai, one of the most important theorists of globalization in the 1990s, emphasized such circulations. In a decisive article (one of the most often cited on globalization), he described a new complex, entangled order, where global flows now circulate freely throughout five transnational ‘landscapes’: an ethnoscape (tourists, immigrants, refugees, exiles, etc.); a mediascape (media, images, and information); a technoscape (knowledge and techniques); a financescape (capital); and an ideoscape (ideologies and counter-ideologies).

However, these landscapes are disjointed: the flows that organize them do not circulate through the same circuits, at the same pace, or in the same way. To Appadurai, the space of global flows is therefore not coherent but explosive, disjunctive, and, more broadly speaking, unregulated.Footnote 61 Among the five landscapes identified by him, two are relevant to the two dimensions of globalization already analysed above: the mobility of people and transnational finance. The other three are directly or indirectly related to cultural flows.

Let us therefore ask again our recurring question: what is new in contemporary cultural globalization? While cultural exchanges have always existed, and deserve to be traced historically, and while cultural flows have been more intense between certain regions at certain times, the current debates on cultural globalization mostly deal with the issue of convergence towards a single global culture. Sociologists try to understand whether globalization is a threat to cultural diversity. Four main models explaining contemporary cultural flows in our current globalization have been articulated by Diana Crane.Footnote 62 The first model emphasizes the notion of cultural imperialism, and includes a criticism of the cultural ‘imperialism’ enacted by the USA. It argues that there has been a global expansion of a market logic in the cultural sector.Footnote 63 And it stresses the dominance of US cultural productions in international trade.

Historically, this notion of imperialism flourished from the 1970s onwards, finding a channel of expression in UNESCO, and a formulation in the 1980 MacBride report, written by the International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems, which emphasized a ‘New World Information and Communication Order’. It also led, in more recent years, to the adoption of the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions in 2005, in order to protect cultural diversity on a global scale.

The second model qualifies this thesis of cultural imperialism and borrows from anthropology to emphasize the notions of hybridity, ‘métissage’, and syncretism. It argues that globalization devalues ‘territorial cultures’ and instead strengthens ‘translocal cultures’. ‘Territorial cultures’ are homogeneous and inward-looking, modelled on national or imperial societies, and circumscribed to regions and communities; they emphasize the notions of authenticity, ethnicity, and identity; and they lead to theories such as ‘cultural imperialism’, the ‘clash of civilizations’, and the ‘Westernization of the world’. Conversely, ‘translocal cultures’ are heterogeneous and outward-looking; they are linked to diasporas and migration, they are developed at crossroads, borders, networks, and intermediaries; they are nurtured by translation, contacts, and cross-fertilization; and they lead to theories of cultural interpenetration, the creolization of the world, syncretism, and hybridity.Footnote 64 One of the best-known formulations of this model is embodied in the concept of ‘glocalization’, coined by Roland Robertson in 1994. Glocalization describes the adaptation of a global culture to local contexts, referring to the deep intertwining of global and local processes. Robertson provides several examples: regional CNN broadcasting, youth hostels, and transnational indigenous movements.Footnote 65

The third model again nuances the cultural imperialism thesis by placing more emphasis on the reception than on the production of cultural goods and content. For example, in this perspective, while American television series or Hollywood blockbusters are seen all over the world, they are not seen in the same way. In sociology, ‘reception studies’ have thus constituted a whole literature that draws on ‘cultural studies’ and Stuart Hall’s pioneering work. Following them, other scholars have emphasized peripheral and regional circulations rather than hegemonic ones, or have argued that the same cultural goods can be marketed in very different ways from one country to another, as dubbing and subtitling of American TV programmes in Europe show.Footnote 66 A fourth model focuses on how national policies can go against the homogenization of cultures and resist it.

Diana Crane thus associates three objectives with national policies in globalization: protecting a country’s culture; developing and maintaining a country’s international image; and supporting national ‘exports’. In sociology, there has therefore been a growing interest in national export policies. In France, for example, Gisèle Sapiro states that ‘the market logic is increasingly confronted with that of the States, which guarantee, through subsidies, relatively autonomous fields of production to resist market pressures’.Footnote 67 Thus, US international domination in cultural industries goes hand in hand with national cultural policies. In France, these policies have led to the defence of the notions of exception and cultural diversity, as far as the movie and television sectors are concerned.Footnote 68

An entire diplomacy specializing in cultural diversity has been built in France. It launched a transnational television channel as TV5 in the 1980s, strongly atypical insofar as it is multilateral, francophone, and cultural, like no other transnational channel. It relied on a network of French diplomats tackling media, TV, and film issues. It supported French exporters selling festival movies on international markets, and subsidized foreign ‘auteur’ films.Footnote 69 This policy, built upon the defence of global cultural diversity, proves that the hypothesis of a global homogenization of cultural productions, and a globalization solely based on the convergence of markets at the expense of cultural diversity and national productions, is too unambiguous. This homogenization actually comes with resistance, and protective and defensive strategies, showing the continuing importance of state and national policies in contemporary globalization.

Social stratification: the rise of a transnational global class?

The question of inequalities between countries in cultural globalization makes it possible to address one last dimension: how does contemporary globalization affect social inequalities? The effects of contemporary globalization on social stratification have generated a whole line of research in sociology. Global inequalities are indeed at the heart of globalization: 5% of the richest people receive one-third of world income, and the Gini coefficient of global inequalities (0.70) is higher than it is in the most unequal countries around the world (0.60 in Brazil and South Africa).Footnote 70 As with the dimensions of globalization previously discussed, however, it can be noted that this problem of inequality was already at the heart of Marx’s analysis in the nineteenth century, when he referred to the global expansion of the bourgeoisie:

The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilisation. The cheap prices of commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls, with which it forces the barbarians’ intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate. It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilisation into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image.Footnote 71

We can therefore repeat the question of the specificity of contemporary globalization with regard to the question of social classes and social stratification. Three types of answers address this puzzle. The first focuses on how the upper classes are benefiting from globalization. A first way to do this is to stress the emergence of a ‘transnational capitalist class’. A homogeneous group of endowed individuals, trained in the same elite universities (mostly in the US and the UK), share business ties, have common interests, belong to the same networks of expatriates, and express a similar cosmopolitan spirit.Footnote 72

This thesis of a transnational capitalist class has, however, been qualified by other sociologists. The work on interlocking directorates of the largest companies in the world suggests rather weak links between members of the business elite, which facilitate business solidarity, more than the existence of a homogeneous group.Footnote 73 Instead of a transnational capitalist class, these sociologists prefer the notion of ‘international capital’, defined as the social property of transnational elites, along with other types of capital: ‘Inseparably cultural, linguistic, and social, largely inherited, reinforced by international school curricula and professional experience in several countries’, it competes with ‘capital produced and legitimized by the state’ and seems to be ‘well adjusted to transformations of the corporate field’.Footnote 74 Globalization is then apprehended through groups of privileged individuals who benefit from a strong international capital mostly accumulated at a national scale.

Several researchers have disputed this stance by focusing on a globalization ‘from below’ or a ‘globalization of the poor’, showing that deprived individuals can also be part of the globalized economy.Footnote 75 They point to informal markets and transnational migrant networks, such as the Afghans who transport goods from Dubai to Europe along informal routes.Footnote 76 Filipino nannies also accumulate various assets during their migratory trajectory to Western countries, as do women specializing in suitcase trading between Russia and Turkey.Footnote 77

A third type of answer stresses a more ordinary globalization, focusing on the everyday work of globalization. It stretches from the elites to ‘ground-level international workers’ and pertains to the entire class system.Footnote 78 Globalization actually extends to a wide range of activities and sectors that are more or less legitimate or highly regarded. Rather than a ‘bourgeoisie invading the whole world’, to quote Marx, contemporary globalization seems increasingly ordinary and pervasive, relating to many professional activities and many workers, who are not necessarily characterized by strong international capital and transnational mobility. In my view, this ordinary character of contemporary globalization points to its specificity in comparison to previous waves of globalization, in which elites, intermediaries, diasporic, and migrant networks were the central figures.Footnote 79 But sociological research on the more ordinary actors of contemporary globalization, and on their social properties and work, is still in its infancy.

Conclusion

In 2005, a British professor of international relations, Justin Rosenberg, published an article titled ‘Globalization theory: a post mortem’, in which he explained that globalization was the ‘zeitgeist’ of the 1990s and that the ‘age of globalization’ was now over. It had lost its relevance after the main events that it had been associated with: financial liberalization and the fall of the Soviet Union.Footnote 80 The comparison between current sociological analyses on contemporary globalization and Marx’s observations on the global expansion of capitalism in the nineteenth century, however, leads us to conclude that Rosenberg’s observation was not entirely accurate. In reality, contemporary globalization is resuming and pursuing previous waves of globalization. Nevertheless, it remains specific, as many sociological studies have shown, focusing on the new complexities and entanglements of our current wave of globalization, which cannot be reduced to a quantitative increase of international trade. I have identified a few dimensions that have been scrutinized by sociologists, who often remain very open to other social sciences, in particular to economics, anthropology, history, political science, and geography.

First, the term ‘globalization’ is new, and is used anachronistically for previous waves of globalization. The novelty of the term alone signals the need to name a new phenomenon. This novelty also explains why the main sociological theories of globalization in the 1990s asserted the beginning of a new global era, which would supersede national societies, contexts, and institutions. Second, in terms of international migration, the emphasis in contemporary globalization has been on the rise of ‘transmigrants’, who maintain regular, intense, and multidimensional contacts with their country and locality of origin. Such transmigrants intrinsically structure transnational communities, inventing new forms of family organization and transnational political engagement.

Third, international trade is less and less based on raw materials and colonial relations of domination, and more and more on goods, logistics, and value chains, and it is characterized by the rise of ‘emerging’ countries. Fourth, the globalization of capital and finance has led to the observation of new forms of spatial structuring of contemporary capitalism, whose command functions are concentrated within a small group of ‘global cities’, which are the capitals of transnational finance, or within nodes and clusters at the heart of the crucial flows and networks of contemporary information capitalism. Fifth, cultural globalization is characterized by a change of scale in cultural exchanges and the circulation of cultural goods, since the rise of a single world culture and global cultural homogenization is now being viewed as a threat to cultural diversity in the world.

Sixth, and finally, sociologists question the impact of globalization on social stratification and social inequalities. Some have pointed to the emergence of a new social class, capitalist and transnational, or the importance of ‘international capital’ among the most privileged social classes to take advantage of globalization. Others, in contrast, highlight the existence of ‘globalization from below’ and ‘of the poor’. In my view, however, the specificity of contemporary globalization is rather to be found in its ordinary character, which affects all social classes and is no longer reserved for certain privileged, intermediate, or marginal actors, as in previous periods.

Romain Lecler is a professor at the Université du Québec à Montréal. He is the author of the handbook Sociologie de la mondialisation (2013), coordinated the Guide de l’enquête globale en sciences sociales, edited by Johanna Siméant (2015), and recently published Une contre-mondialisation audiovisuelle. Ou comment la France exporte la diversité culturelle (2019).