Introduction: the study of non-Western music in global history

Modern historians have increasingly questioned the Eurocentric master narrative of the global diffusion of science and the Enlightenment as two supposedly unique Western consequences of the Renaissance, humanism, and the Reformation. On the contrary, they have argued, modernity resulted from ‘a complex parallelogram of forces constituted by economic changes, ideological constructions, and mechanisms of the state’. Against the background of the long history of the integration of the world, these forces were driven by a variety of different centres, not just those in the West.Footnote 1 Accordingly, the Enlightenment, too, should not be understood ‘as the sovereign and autonomous accomplishment of European intellectuals alone’, but as the product of and response to ‘global conjunctures’ and ‘the work of many authors in different parts of the world’.Footnote 2 Considered globally, scientific and Enlightenment ideas in the non-Western world ‘mingled with and were empowered by ideas derived from indigenous rationalistic and ethical traditions’.Footnote 3 Important parts of what came to be seen as Western science ‘were actually made outside the West’.Footnote 4 Furthermore, Enlightenment ideas continued to be reinterpreted outside Europe into the nineteenth century. In the age of liberalism and empire, they were increasingly inserted into narratives of evolutionism and the advance of civilization, and became central to newly defined social reformist, (inter-) nationalist, and civilizing ideologies.Footnote 5 Indeed, as liberal non-Western reformers generally adhered to ideas about improvement, education, law, and individual rational beings leading a self-conscious life,Footnote 6 they would ultimately take the lead ‘in pronouncing claims to equality and to Enlightenment promises’.Footnote 7

The present article investigates how non-Western national music fits into this global history, in which the far-reaching influence of reinterpreted liberal and earlier Enlightenment ideas and the processes of empire-building were fundamental components. Thus far, global historians have preferred to examine politico-economic rather than cultural topics and visual rather than aural culture. In consequence, the study of music, that quintessentially non-representational medium, has been neglected. Besides academic disciplinary boundaries, this disregard has much to do with the dominant view of music as a purely musical phenomenon that essentially transcends time and place and should be studied on its own. Yet music, too, provides a lens through which to examine historical continuity and change, assuming that it is closely embedded in societies and formative to their construction, negotiation, and transformation in terms of consensus and conflict. In addition, the few historians who have examined music in global history have largely restricted themselves to the period before the second half of the nineteenth century and to two dominant modes of inquiry: on the one hand, they have looked at the dissemination and use of European music around the world;Footnote 8 on the other, they have discussed the hybrid results of the interactions between European music and non-Western music traditions.Footnote 9 For their part, ethnomusicologists have accorded little attention to global history scholarship and have generally continued to assume that the legacy of the Enlightenment and the development of modern science were specifically unique Western experiences that diffused from Europe around the globe.Footnote 10 As global historians have made clear, however, European overseas expansion was never simply a narrative of actors and reactors, nor did change solely come from the West and the responses from the rest.Footnote 11 Non-Western societies had their own internal dynamics and, accordingly, the imperial encounter generated unpredictable reactions, initiatives, and interrelated results simultaneously in the West and elsewhere.Footnote 12

In 1985, the well-known ethnomusicologist Bruno Nettl argued that the impact of Western music and musical thought in modern history did not mean ‘the death-knell of musical variety in the world’ but, on the contrary, led to ‘a state of unprecedented diversity’.Footnote 13 Yet twenty-five years later, in the context of contemporary globalization, he believed that there was too much homogenization in music and that this made elites worldwide musically wealthier, but the globe ‘poorer musically’.Footnote 14 The shift in Nettl’s ideas is particularly relevant to the topic discussed here. While his first statement is still typical of the view of those who look favourably on contemporary globalization, his second directly connects to a thus far largely unremarked result of European expansion, to which Nettl himself does not refer: namely, the globalization of Western equal temperament tuning, and, one could argue, modern functional harmony, which is based upon the relationship between major and minor keys.

These globalizing influences came at the expense of local use of systems of intonation and microtones, which are characterized by intervals between notes that are smaller than the semitone (the smallest difference between two pitches in Western music). Over the centuries, various temperaments or tuning systems had been used in the West, but eventually that known as equal temperament replaced others based on acoustic intervals as naturally heard by the human ear, which are not equally spaced. In equal temperament tuning, each interval is adjusted or tempered equally and thus everything is equally a little bit out of tune. It emerged not only as the foundation of modern harmonic hearing and thinking but also as the tuning system for the piano, whose pitches are fixed. By dividing the octave into twelve semitones of equal size, all scales can be played in any key with minimal perceived differences in intonation.Footnote 15 Hence, although European guitars had been disseminating equal temperament around the world since the sixteenth century,Footnote 16 the piano in particular became essential to this process from the nineteenth century onwards. After their exposure to European equal temperament, tonality, and music theory, non-Western music reformers reinterpreted the world of music in a variety of ways, ranging from the implementation of Western music in East Asia to the adoption of equal temperament tuning, though at non-diatonic intervals,Footnote 17 and/or scientific classification systems of tonal material in the Arab world and elsewhere. Thus, at least in this fundamental intellectual manner, a trend towards musical homogenization, as noted by Nettl in modern times, had already begun centuries earlier.

In this context, then, this article comparatively explores sameness rather than difference in non-Western national musics in an increasingly interconnected global public sphere. In doing so, it recalls C. A. Bayly’s idea of the manifold appearance of global uniformities in the formation of modern states, religions, political ideologies, and economic life, as these developed out of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth.Footnote 18 In his view, ‘this growth in uniformity was visible not only in great institutions such as churches, royal courts, or systems of justice’, but also in what he calls ‘bodily practices’ or ‘the ways in which people dressed, spoke, ate and managed relations within families’.Footnote 19 At the same time, he traces the ways in which global connections heightened ‘the sense of difference, and even antagonism, between people in different societies, and especially between their elites’, while highlighting how ‘those differences were increasingly expressed in similar ways’ after 1890, during the age of ‘hyperactive nationalism’.Footnote 20 Characteristically for the field, Bayly hardly refers to music; hence, among other things, this article supplements his work.

At the outset it should be stressed that the argument about global uniformities cannot be pushed too far. Beneath the appearance of formal similarity and mutual translatability, significant sonic and cultural differences remained. Instead of an all-powerful force for homogeneity, the rising trend towards uniformity was often ‘contested, partial, and uncertain in its outcome’.Footnote 21 So, for example, non-Western musicians appropriated guitars in numerous ways, in accordance with their own needs and agendas, and with different results. Be that as it may, this article is intended as a contribution to global history scholarship rather than an in-depth study of music from specific cultural areas and hence it principally attempts to establish global parallels and comparisons in the context of long-term historical change and interaction.

Liberalism, empire, and national music in a global public sphere

The trend towards global standardization in non-Western national musics emerged from the (late) nineteenth century when elitist music reformers, often with state support, canonized and institutionalized music traditions from the Arab world to Brazil. Fundamental to these transformations was the worldwide creation of public spheres during the modern processes of state formation, accelerated by the growing dominance of print culture, urbanization, the proliferation of voluntary organizations, and the improvement of communications through technological developments such as steamships, railways, the telegraph, and the telephone. As knowledge circulated faster than ever before, the world was becoming ever more connected intellectually. Non-Western elites were impressed by liberal and former Enlightenment ideas, which they themselves increasingly developed and invoked to legitimize their calls for modernization in different fields, including music.

Intellectual interactions between the local and the global were especially played out in cosmopolitan centres such as Batavia, Bombay, Cairo, Calcutta, Istanbul, Rio de Janeiro, Shanghai, and Tokyo, to name only a few. Here, local intelligentsias acted as surrogates for the nation and equally were beneficiaries as interlocutors of a burgeoning and worldwide public sphere. Imbued with modern thinking, they formed a globally imagined community. At the same time, however, these elites became locally entangled in the reinterpretation of culture. Following the earlier Enlightenment quest for origins, as part of ‘the general trend toward historicizing science and philosophy’,Footnote 22 they increasingly looked for the cultural foundations of their community, nation, and, indeed, music. In the process, they (re)constructed history in ways that emphasized cultural continuity in order to legitimize the present.

The modernization of non-Western music was fostered by the global spread of European musicians and instruments. From the beginning of European overseas expansion, Western musical instruments were frequently given as presents to important non-Western rulers, as in the famous case of ‘keyboard diplomacy’ between the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) and the Chinese emperor.Footnote 23 Non-Westerners were often impressed by the technological quality of Western instruments,Footnote 24 especially keyboards and later of course music-recording equipment (about which more below). In addition, they gained familiarity with European music, especially through Christian hymnody and military (brass) bands (see Figure 1).Footnote 25 Initially associated with missionary activity, church choirs and military bands developed into music schools, and often evolved into European-style conservatories. For the most part, these institutions employed European teachers but they were also recruited by indigenous courts as non-Western rulers sought to demonstrate their authority to Western visitors and their own populations through representations perceived as ‘modern’. For example, Guiseppe Donizetti (1788–1856), the older brother of the famous Italian opera composer, and Alfred Jean-Baptiste Lemaire (1842–1909) were appointed at the Ottoman and Persian courts respectively to oversee the training of the European-style military bands and to introduce European music more generally. Though Donizetti’s newly created imperial band replaced the military band of the Ottoman sultan’s elite troops or Janissaries (the mehter) and grew directly out of its model, it was considered superior, mainly as a symbol of modernity. Furthermore, Donizetti and Lemaire composed national anthems for the two empires.Footnote 26 On the other hand, although opera houses were built in Rio de Janeiro (c. 1760), Calcutta (1827), Cairo (1869), Hanoi (1911), and other non-Western cities (see Figure 2), they represented Western authority and usually remained out of bounds for local populations.Footnote 27

Figure 1 The band of the first mobile artillery bodyguard brigade, Istanbul, c.1880–93. Source: courtesy of the US Library of Congress.

Figure 2 Italian opera house, Cairo, c.1900. Source: courtesy of the US Library of Congress.

As non-Western music reformers began to compare their own music traditions with that of Europe, they became aware of the work of ‘comparative musicologists’, whose ways of thinking were infused by scientific concepts and terminology, such as evolution, diffusion, selection, and adaptation. They were also preoccupied by technical and practical problems relating to the mechanics of sound production, recording, and tuning. Subsequently, the emergence of ethnomusicology involved a fundamental methodological and ideological shift away from comparison and into a relativistic paradigm, namely the study of music in culture.Footnote 28 According to comparative musicologists, Western music had progressed from ‘primitive’ forms to the high point of contemporary classical. In this context, then, non-Western music reformers began to wrestle in original ways with theories about the origins of music and its subsequent social evolution.

Then again, Enlightenment thinkers in search of the origins of music had been preoccupied with the existence of ‘a universal folk scale’, which, according to thinkers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–78), was pentatonic.Footnote 29 Moreover, following Charles Burney (1726–1814), William Jones (1746–94), and many others, music researchers saw similarities between the music of ancient Greece, the music of China, and European folk music.Footnote 30 For example, the founding father of the early twentieth-century English folk-song movement, Cecil Sharp (1859–1924), claimed that the pentatonic scale was ‘known to the ancient Greeks’ and was ‘still used by the peasant-singers of Scotland and Ireland, and also by the natives of New Guinea, China, Java, Sumatra, and other Eastern nations’.Footnote 31 By this time, many elitist non-Western music reformers had also become preoccupied with the theoretical division of scales into intervals from a comparative perspective. Some of them actually saw the absence of harmony in their own music as a sign of inferiority to Western music and as a reason to adopt tonal harmony and/or equal temperament tuning,Footnote 32 while others, particularly in British India and the Dutch East Indies, chose to systematize their own music traditions scientifically.

Frequently in interaction with the work of Western Orientalists and musicologists, non-Western music reformers thus self-consciously redefined themselves in different ways as modern and national musical subjects. Among their main activities were: the establishment of modern music educational institutions; the rationalization of music theory; the collection of music in staff notation or (reformed) indigenous notational systems; the definition of canonical composers and repertoire; the publication of music manuals and self-instruction books; modern concert arrangements; and the organization of music conferences.

To a great extent, these music reforms overlapped with what happened in national music formations in Europe on the basis of folk music and, moreover, were in agreement with the Western civilizing mission that took place simultaneously in the West and elsewhere.Footnote 33 In fact, as Matthew Gelbart has argued, European folk and art categories had a definite influence on the ways in which non-Westerners looked at their own music traditions, ‘either by imposing Western art music as an external hegemonic practice in different countries, or by making the distinctions between indigenous “high” and “low” styles more rigid and predetermined’.Footnote 34 Simultaneously, it should be noted that non-Western modes of reformist thinking had a multiple intellectual lineage. In India, for example, a reinterpretation of the ancient marga (classical) versus desi (non-classical) distinction in music was incorporated alongside Western ideas.Footnote 35

The invention of Thomas Edison’s phonograph in 1877 not only immensely aided the work of comparative musicologists (see Figure 3), but also played an important role in the growing awareness among non-Westerners of their own music traditions in a comparative perspective. Following the phonograph companies’ search for new markets, the story of the industry simultaneously became one of discovery of non-Western music.Footnote 36 During the first decade of the twentieth century, British Gramophone cut 14,000 discs in Asia and North Africa.Footnote 37 In 1909, it specifically sent a collector across the Caucasus and Central Asia ‘to find music fodder for the markets of the Russian Empire’ and, while the corporation had been doing business in the region since 1901, by the time of the 1917 Revolution ‘it had produced four thousand recordings’.Footnote 38

Figure 3 The Dutch musicologist Arnold Bake recording with a phonograph at the Maligawa temple in Kandy, Ceylon, in 1932. Source: courtesy of Leiden University Library, Arnold Bake Collection: box no. 10; album 02-0214.

In this way, unintentionally, the industry preserved and popularized non-Western music, though the targeted audiences remained local rather than global. Furthermore, as A. G. Hopkins put it, ‘in improving their balance sheets, the record companies inadvertently assisted the rising cause of colonial nationalism by adding to the store of indigenous cultural traditions’.Footnote 39 At the same time, the industry generally aimed to record authentic music untouched by Western influence and, in doing so, it helped to foster a mode of thinking that would prove fundamental to the development of metropolitan interest in non-Western music. In retrospect, the networks of the phonograph companies provide persuasive evidence for the argument that the beginnings of the globalization of the music industry should be placed at the beginning of the twentieth century instead of towards its end, as is conventional.

Eventually, the canonization and institutionalization of non-Western national music took place between the two extremist poles of the adoption of Western music and simultaneous neglect of indigenous music (Japan), and the rejection of Western music but modernization of high-cultural traditional music (India). All non-Western music reformers nonetheless aimed to place their high-cultural music traditions on the same level as Western classical music. Sometimes this ideologically promoted process of classicization resulted in the ossification of music repertoires and performance practices, as in the cases of Japanese imperial court music (gagaku) and ‘traditional’ music ensembles in Central Asia. As the result of (Latin) America’s specific histories of European overseas expansion and slavery, the making of national music in the New World was of an altogether different kind; for example, in Brazil it came to be based primarily on primitivist views of African music. As elsewhere in the world, however, Brazilian music reformers adhered to the idea that their redefined national music traditions were authentic.

Music, nationalism, and Westernization: Japan and China

By and large, Japanese music modernizers firmly believed in the superiority of Western music. As a result, the Meiji government introduced a compulsory national music class in elementary schools, which consisted of Japanese lyrics set to Western melodies that were generally based on European and American hymns and folk songs. In this, they were helped by Western Christian missionaries, who were largely ‘responsible for the development of congregational singing’ and ‘the spread of general popular singing of Western melodies’.Footnote 40 The key figure behind the government’s Westernizing programme was Isawa Shuji (1851–1917). During his studies in the United States, he ‘became well aware of the significance of vocal music education at an elementary level and intended to introduce it to Japan’.Footnote 41 It was far better, he argued, ‘to adopt European music in our schools than to undertake the awkward task of improving the imperfect oriental music’.Footnote 42 He was later not only the founder-rector of the Tokyo Academy of Music (1887) but also fundamental to the music education programmes in Japan’s colonies, Taiwan and Korea.

Like other Japanese national music reformers and musicians, Isawa was a great believer in natural scientific laws and evolution in music. He thought that Western music was ‘superior to any other form of music due to its thorough rationality and universal validity’ and that staff notation was ‘the only appropriate and effective way to describe sounds’.Footnote 43 He also had very utilitarian ideas about the creation of a national Japanese music. In his opinion, singing advanced the physical development of pupils ‘by strengthening the lungs, activating circulation and improving their build’; moreover, unlike Japanese imperial court music and folk music, it had a decisive moral and patriotic influence.Footnote 44 He looked down upon folk music and launched a programme to reform these ‘vulgar tunes’ through harmonization, so that they would meet ‘the high standards of the civilised age’.Footnote 45 Yet, although Isawa thought that contemporary Western music was currently superior to that of Japan, he contended that the situation had been different in the past. In pursuing this argument, he appropriated the earlier Enlightenment search for the origins of music, pointing out that the music of the two civilizations derived from one common historical source. He not only ‘insisted that the Japanese scales, called ritsu and ro, were basically identical with the ancient Greek tonality’ but also emphasized that this was no coincidence: ‘Every kind of music both in the Occident and the Orient originated from a single source in ancient India and just developed thereafter separately.’Footnote 46 Undeniably, this idea of an Asian golden age in music, which saw Asian civilization as not only equal to that of the West but its superior in terms of musical origins, was meant to heighten the nationalist self-esteem of the Japanese and of Asians at large.

In the footsteps of Isawa, Japanese comparative musicologists focused primarily on Asian and especially on Chinese classical music. This search was initiated in particular by the national music reformer and musicologist Tanabe Hisao (1883–1984), who wrote more than thirty books about Asian music, partly based on research in Korea, China, and Taiwan, Japan’s oldest colony. In accordance with the well-known national slogan ‘Japanese spirit, Western technique’, he strongly supported the renewal of Japanese music traditions through modernization without Westernization. Overall, he adhered to an evolutionary and indeed imperial view of music history from a Japanese perspective. So, for example, he acknowledged that the musical culture of the Tang dynasty had set the standard for East Asia in earlier periods, but at the same time he believed that it had authentically survived in Japanese imperial gagaku, where the performers were generally the same individuals who propagated, or at least studied, Western music.Footnote 47 Hence, he wondered whether the time had not arrived for Japan to lead Chinese music into a second period of achievement and global renown by way of the Japanese ‘synthesis of the Eastern and Western cultures’.Footnote 48 Tanabe assumed that Meiji Japan’s progress showed that the country ‘was no longer a disciple of China, but the master whose role it was to develop the once-great tradition of Asia to modernity’.Footnote 49 In his opinion, therefore, the repatriation of gagaku, as preserved in its primordial form in Japan, to China, Korea, and Manchuria signified the expansion of a highly moral and spiritual Confucian music. Indeed, modern ideas generally blended in East Asia with the existing Confucian cosmology, ‘which in turn was refashioned under conditions of global interaction’.Footnote 50 By thinking in this way, Tanabe not only perceived East Asian gagaku as being morally and spiritually superior to Western music but also culturally justified Japanese conquests abroad.

In 1936, Tanabe was one of the founders of the Society for Research in Asiatic Music. The focus of the society and its journal was Asian classical rather than folk music traditions. Its members discussed and distrusted the Asian music research of Western musicologists, who in their eyes could not understand the Asian spirit or ‘grasp the ideology of the unity of Asia beyond ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity’.Footnote 51 Tanabe was explicitly critical of the exotic and Eurocentric focus of the Music of the Orient series of recordings (1934), compiled by Erich Moritz von Hornbostel (1877–1935), one of the founders of comparative musicology:

Japan is represented only by popular and folk songs; no songs from Manchuria and Mongolia are included; three ‘extremely unpleasant and unartistic’ drama songs are heard from China; five Balinese tunes – a number out of proportion to their cultural importance in Asiatic music history – appear because of their exotic appeal for Europeans; from India, vocal music is included instead of more artistic instrumental music; no Arabic music tracks are selected, but instead there are items from Egypt and Tunisia …Footnote 52

In response to von Hornbostel’s work, Tanabe edited what in his eyes was a proper scientific musical anthology, Music of East Asia (1941), with music from Manchuria, China, Mongolia, Java, Bali, Thailand, India, and Iran. Ironically, however, only the music of the first three countries consisted of original recordings, while the rest were recycled materials, without credit, from von Hornbostel’s collection. Ultimately, Tanabe’s search was a moral and spiritual one, wherein he envisaged Asian music as superior to Western music. The anthology remains a representation of a self-orientalizing idiom of cultural nationalism in terms of uniqueness, spirituality, and unity of Asian music,Footnote 53 as well as of the Japanese interaction with, if not dependence on, Western musicological research.

The case of Japan is of further importance because its ‘Asianized’ modernity led to a refraction of scientific and liberal thinking in Asia. Japan attracted not only anti-imperial Asians from Cairo to Peking but also students from China, Taiwan, and Korea (the last under Japanese rule between 1905 and 1945). Particularly after the country’s military victories over China (1895) and Russia (1905), many Chinese went to Japan to study and learn about the secrets of progress and so created ‘what was then the biggest-ever mass movement of students overseas’.Footnote 54 On their return, music students began the school song movement that was subsequently adopted by the Qing Dynasty government. In line with music reforms in Japan, they set Chinese lyrics to borrowed Westernized Japanese school songs, introduced Western music terminology, and invited numerous Japanese educators to spread the practice of school song. By and large, these music reforms conformed to the New Culture Movement of the 1910s and 1920s, which called for the creation of a new Chinese culture based on Western standards, especially of democracy and scientific knowledge. They were generally supported by the state, though obviously not as much as in Japan because the early twentieth-century Chinese state was anything but strongly organized.Footnote 55

The educator and President of Peking University, Cai Yuanpei (1868–1940), who had studied in Germany, ‘aimed to introduce Western classical music and reform Chinese music by eliminating its deficiencies and making it more “scientific”’.Footnote 56 In 1921, his efforts led to the establishment of Peking University’s Institute for the Promotion and Practice of Music, where, among other things, Western violin technique was applied to the playing of the erhu, the traditional instrument often referred to today as the Chinese violin, so that it became a virtuoso solo instrument for which numerous compositions were created. In due course, left-hand techniques of fingering and positioning, including pitch glides, trills, and grace notes, and right-hand bowing techniques, including tremolos and pizzicato, were introduced. The instrument’s silk strings were replaced by steel ones to produce a louder and clearer sound. In 1927, Cai co-founded and became the first President of the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, which, next to the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra, did most for the education and proliferation of Western music in China.

The place of Western music in Chinese society became more ambiguous after the Communist Revolution of 1949: on the one hand, it continued to be a marker of China’s modernity; on the other, it stood for ‘decadent’ foreign and bourgeois values. Besides the ‘model operas’ that were introduced during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), folk music provided an acceptable alternative, since interest in Chinese folk music had grown steadily from the 1930s. Initially, folk songs were used for Communist political propaganda in defence against the Japanese enemy. Following the Yan’an Talks of 1942 by Mao Zedong (1893–1976) on the role of literature and art in the Communist state, expurgated versions without religious or erotic content were adapted for the creation of harmonized revolutionary songs and larger musical works to educate the illiterate rural population about the goals of the Communist Party. Furthermore, a Chinese national classical music tradition was invented that translated folk melodies and certain traditional instrumental techniques into a Western idiom of pentatonic romanticism. The two most famous pieces in this state-propagated tradition are the Yellow river cantata (1939), composed by Xian Xinghai (1905–45), who studied composition at the Paris Conservatory, and the Butterfly lovers’ concerto (1959) for violin and orchestra, composed by Chen Gang (b. 1935) and He Zhanhao (b. 1933).

Successively, the Communist government implemented a civilizing mission towards folk music. Folk instruments were rebuilt into modern ones and tuned in equal temperament. Western performing techniques were introduced, as well as orchestras using traditional instruments but modelled after the Western orchestra. In 1964, the China Conservatory of Music in Peking was specifically founded for the purpose of performing, studying, and inheriting folk music, and similar departments were established at countless music educational institutions around the country. Despite all this, however, music modernizers claimed that their national music was spiritually and authentically Chinese.

Conversely, the making of national Chinese classical and folk music was much influenced by the presence of Russians musicians and Soviet policy at large. Over the course of the 1950s, Russians ‘were instrumental in building not only orchestras, but also ballet and opera companies and virtually the entire performing arts system’.Footnote 57 One important early figure was the renowned pianist and composer Alexander Tcherepnin (1899–1977), who made several extended visits to China and Japan between 1934 and 1937. He encouraged Chinese and Japanese composers to create national music and even founded his own publishing house in Tokyo for the promotion of their work. In 1936, his piano method was based on what he saw as ‘China’s pentatonic scale’; in doing so, he adopted an influential mode of thinking introduced by Enlightenment scholars such as the Jesuit Jean-Baptiste Du Halde (1674–1743) and especially Jean-Jacques Rousseau.Footnote 58 It was followed by Technical studies on the pentatonic scale, op. 53, ‘which was soon adopted by the government as the official piano method and used in lessons throughout the country’.Footnote 59 Though there had indeed been a pentatonic scale in China since ancient times, the piano was tuned in equal temperament, while Chinese instruments traditionally played this scale with pitch differences that occur naturally. Otherwise, as far as I know, Chinese national music reformers never referred to the fact that the exact calculation of equal temperament might have been first invented in China.Footnote 60

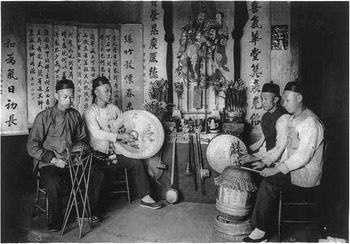

All things considered, including the Communist Party’s restrictions on the performance of Western music during the Cultural Revolution, elitist Japanese and Chinese national music reformers increasingly departed from their own (folk) music traditions, despite the fact that these were still alive (see Figure 4).Footnote 61 Furthermore, they relegated their high-cultural music traditions largely to museum pieces. In Japan, gagaku was redefined to strengthen national identity in terms of the monarchy. In China, Peking opera was refurbished as a national essence similar to Western classical opera and became personified by the genre’s most celebrated star, Mei Lanfang (1894–1961), who successfully toured the United States in 1930.Footnote 62 Peking opera was also patronized by the Taiwanese elite under Japanese colonial rule (1895–1945) to reinforce their Chinese identity and link with mainland China, where opera troupes were hired until Japan’s invasion of China in 1937. Moreover, after the Communist Revolution, the Taiwanese government supported Peking opera as national music to the virtual exclusion of the widely popular local performing traditions.Footnote 63

Figure 4 . Four Chinese playing traditional percussion instruments with string and wind instruments in their midst, c.1904. Source: courtesy of the US Library of Congress.

However, the search for the origins of Chinese music proved to be more complicated for Chinese musicologists than for their Japanese counterparts. Like the Japanese, they recognized the music of the Tang dynasty as a pinnacle of Chinese culture, but simultaneously realized that the music of that period had been heavily influenced by that of Central Asia and elsewhere along the ‘silk road’. Hence, in his Music of the Oriental nations (1929), the founding father of modern musicological studies in China, Wang Guangqi (1892–1936), ‘identified three global cultural centres (Greece, Persia, and China) and drew a map of pathways of dissemination and interaction from each’.Footnote 64 Guangqi had studied musicology and organology in Germany under the comparative musicologists von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs (1881–1959) and in 1934 he had received his doctoral degree in musicology in Bonn. In his numerous writings, he frequently compared Chinese and Western music. From an evolutionary perspective, he saw Western functional harmony as the highest form of tonal development and he staunchly advocated the creation of a modern Chinese national music along Western lines. Simultaneously, however, he believed in the superiority of Chinese music because it was based on the Confucian ideals of music, as a counterpart of ritual and spiritual harmony. What he saw as the peace-oriented and modest character of the Chinese contrasted with the ‘Westerners’ penchant for fighting battles and inclination to compete for individual fame and profits’.Footnote 65

Music and nationalism in the core Muslim world

For centuries, the core Muslim world from Central Asia to Morocco, dominated by Arabic, Persian, and Turkish languages, shared an elitist and urban pan-Islamic music culture. It was much influenced by, among others, the music theoretical treatises of al-Farabi (c.870–950), Ibn Sina (980–1037), and Safi ad-Din al-Urmawi (c.1216–94), and in most places by the subsequent spread over more than three hundred years of Ottoman culture, with musicians travelling from court to court and performing a Turkish–Central Asian canonical music repertoire. During the imperial encounter, then, the different melodic scales, known as maqam in Arabic and Turkish and dastgah in Persian, were generally systematized and equal temperament tuning had been adopted, though there remained significant musical differences, as in the use of instruments and microtonal material, between the Maghreb (the Arab Andalusian tradition of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia), the Mashreq (Egypt, Syria, Iraq, and so on), Persia, Central Asia, and Turkey.Footnote 66

The first Congress on Arab Music, held in Cairo in 1932 under the patronage of the Egyptian king, Fu’ad I, was a turning point in twentieth-century Arab music. Fu’ad and the organizers used this term to replace the more common expression ‘Oriental music’ and hence the congress was also a manifestation of Arab nationalist sentiment, in keeping with the idea of the existence of a ‘Muslim world’ that had emerged in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 67 Even so, as Jonathan Holt Shannon emphasized:

referring to the melodic and rhythmic practices of the Arabs as ‘music’ (musiqa) was not unproblematic because prior to the modern period the term referred primarily to theories of music and not to an autonomous realm of instrumental practices; Arabs tended to call their melodic and rhythmic practices ghina (song) or inshad (chant), revealing the privilege of the voice in Arab aesthetics.Footnote 68

Though most participants came from Egypt, there were scholars, musicians, and music ensembles from Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. Delegates discussed the present and future of Arab music not only with each other but also with European counterparts such as the comparative musicologists von Hornbostel, Sachs, and Robert Lachmann (1892–1939), the Arab music scholar Henry George Farmer (1882–1965), and the famous composers Béla Bartók (1881–1945) and Paul Hindemith (1895–1963).

In general, the Europeans saw Arab music as linked to the past, but favoured the preservation and research of ‘primitive’ folk music, which they believed contained the authentic spirit of Arab music. In contrast, most nationalist Arab music reformers were disparaging about folk music and favoured a radical modernization of their classical music traditions. In doing so, they took the Western evolutionary scheme of music – that is, from ‘primitive’ music to Western classical music as the highest stage to be reached – as the ultimate referential model. They envisaged a musical renaissance of Arab music along similar lines.Footnote 69 Nonetheless, they argued, these modernizing efforts would not impair the inherent authenticity and spirituality of Arabic music. In fact, they believed that modern Arabic music would be a revival of a past golden age, finding support in the work of Western Orientalist scholars such as Henry George Farmer. In A history of Arabic music to the XIIIth century (1929) as well as in other writings, Farmer had argued passionately for the strong past influence of Arab music over European music. Another source of inspiration was Rudolph d’Erlanger (1872–1932), who wrote the six volumes of La musique arabe (1930–59) and during the 1920s helped to revive the Arab Andalusian music tradition known as ma’luf in Tunisia.Footnote 70 In contrast, Arab music reformers were hesitant about the origins of their music. They generally considered the Umayyad and Abbasid eras to be the golden age of Arab music, but they also realized that it was much indebted to Persian music and that afterwards, under Ottoman rule, it had incorporated influences from Turkey and Central Asia.

The main discussion points at the congress were the precise definition of an Arabic scale and intonation, the classification of the melodic scales (maqam), and the problem of notation. Unlike the Westerners, most Arab reformers advocated the introduction of an equal-tempered Arabic scale of twenty-four quarter-tones, analogous to the European equal temperament tuning, because this would help rationalize Arab music and also allow functional harmony. Like some Arab congress participants at the time, many Arabs have since complained that such a tuning does not capture the nuances of Arab music, ‘which for them does not have uniform pitch intervals’.Footnote 71 Following the congress, however, the equal-tempered Arabic scale has been taught as the standard in Arab conservatories and has had a definite impact on modern Arab music practice.

In addition, Arab music reformers created orchestras using both traditional and Western instruments in order to preserve their classical musical heritage in a modern outfit. The Western violin soon gained a dominant presence and replaced traditional string instruments. Umm Kulthum (1904–75), who later became the most popular singer of the Arab world, performed at the congress with such an orchestra, the members of which wore black tuxedos, bow ties, and the fez, that sign of West Asian modernity (see Figure 5). The presence of the ‘traditional’ orchestras in the Arab world today reflects the continuing importance of the views of the Arab music reformers at the 1932 congress. Most important, however, is the fact that the performers in these orchestras aesthetically distanced themselves from that fundamental element in traditional Arab music, improvisation, and overall adapted their former more individualist musicianship to ensemble playing.

Figure 5 Umm Kulthum and her orchestra at the 1932 Congress on Arab Music. Source: Recueil des travaux du Congrès de musique arabe, Le Caire: Imprimerie Nationale, Boulac, 1934.

Partially because of direct (Russian imperial) state involvement, music reforms had a greater impact in Persia, Russian Central Asia, and Turkey than in the Maghreb and the Mashreq. In a manner similar to developments in the latter regions, the classical dastgah and maqam repertoires were consolidated as national music in Persia and Russian Central Asia.Footnote 72 In Persia, the music reformer Ali Naqi Vaziri (1886–1981), who had studied Western music in Paris and Berlin, rationalized Persian classical music on a Western pattern and defined a twenty-four quarter-tone scale as its basis. In general, he had an immense influence on the modern development of Persian classical music through his teaching, writings, organization of Western-style concerts, and so on. After his appointment as director of the Tehran Conservatory of Music in 1928, he received explicit state support to introduce music, including the singing of patriotic songs, to the curriculum of elementary schools.

As was to be expected, national music reformers such as Vaziri also argued that the origins of Persian music lay in the pre-Islamic Sasanian period (226–642) and that it had exercised a heavy influence on subsequent Arabic music. Nonetheless, in 1934 Riza Shah (1878–1944), the founder of the Pahlavi dynasty, visited Turkey and was greatly impressed by Atatürk’s modern reforms. Accordingly, he found Vaziri’s initiatives insufficiently modern and dismissed him as director of the Conservatory. During the following decade, Western classical music was favoured by the elite in Iranian society. After Riza Shah’s abdication, however, Persian classical music, partly as propagated by Vaziri, experienced a revival. Yet, more than anywhere else in the core Muslim world, with the exception of the ma’luf repertoire in Tunisia perhaps, it solely did so as an ossified sacrosanct repertoire, with musicians using staff notation, suitably amended, and instruments tuned in equal temperament. In Central Asia, where the situation was generally comparable to that in Persia, ‘traditional’ orchestras even began to perform Western classical music on modernized indigenous instruments, as in China and Mongolia under Russian influence.Footnote 73

Music reforms in Turkey were exceptional in the core Muslim world. Under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881–1938) and strongly influenced by the writings of Ziya Gökalp (1876–1924), large state-supported Westernization programmes were introduced. At the same time, the state authorized the collection and research of Turkish-language folk songs, which became the basis for modern Turkish national music. This national folk music project led to the prohibition of music that invoked Central Asian–Persian classical music, the Sufi tradition (which flourished at the Ottoman courts), Islamic music more broadly, and any ‘gypsy’ associations. To a great extent, therefore, these initiatives overlapped with the creation of a modern Turkish language purged of Arabic and Persian loanwords.

Once again, Bartók and Hindemith were interlocutors.Footnote 74 Though Hindemith was only involved for a brief period in the setting up of a Western-style conservatory in Ankara, Bartók played a significant role in the making of Turkish national folk music. In 1935–36, the government invited him to conduct a major expedition in south-eastern Turkey and to teach younger Turkish folklorists how to collect, transcribe, and analyse folk songs. On the basis of his fieldwork and Edison phonograph recordings, Bartók created a collection of precisely detailed notations and song analyses that continue to be important to this day. This is especially so because after he left his work was continued by the modernist composer Ahmad Adnan Saygun (1907–91), and other folk-song students who had worked with Bartók at the time.

Like most other folk-song researchers, Bartók saw the pentatonic scale as the primordial universal scale from which all others had developed. Influenced by contemporary theories about the Ural–Altaic linguistic group, he believed that the oldest forms of Hungarian music and Turkish music were linked through their common pentatonic melodies. In doing so, he strengthened the nationalist search for the Central Asian origins of Turkish music by Saygun and other folk music collectors, which had already begun before his arrival. For them, pentatonicism was the seal of authentic Turkish music because it showed that the folk songs originated from Central Asia. While composers such as Saygun appropriated Turkish folk music in their Western classical compositions – a tradition that still continues on a small scale – the main long-term result of early twentieth-century state-supported folk music research in Turkey, as heard and seen on Turkish radio and television, was the establishment of folk music schools and orchestras, with refurbished traditional instruments tuned in equal temperament, throughout the country.Footnote 75

Classical national music in the Dutch East Indies and British India

The idea of equal temperament tuning was not adopted in Asian high-cultural musical traditions, such as in Japanese gagaku and Peking opera in China and Taiwan. Yet, while these latter music traditions became more or less ossified, in contrast, the Javanese court ensemble music (gamelan) in the Dutch East Indies and the north Indian (Hindustani) and south Indian (Carnatic) classical music traditions in British India remained very much alive. Nonetheless, in the same manner as their counterparts elsewhere, the Javanese elite classicized gamelan as national music along the lines of Western classical music (see Figure 6).Footnote 76 Since the beginning of the nineteenth century, its practitioners and patrons had often worked together with Dutch Orientalists and musicologists, of whom Jaap Kunst (1891–1960) remains the most famous. In consequence, Javanese musicians and music theorists became fascinated with the notation of gamelan pieces, in both staff and local notation systems; with the so-called balungan part as a fixed melody; and with the description and comparison of tuning systems (pelog, slendro, and so on). Furthermore, in accordance with the Dutch Orientalist search for the origins of authentic Javanese culture, the Javanese national music reformers saw gamelan music as the product of a pre-Islamic golden age of Hindu–Buddhist Javanese culture.

Figure 6 Javanese gamelan and topeng masked dancers, World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. Source: courtesy of the US Library of Congress.

Compared to other countries in Asia, the high-cultural music scene in British India was most varied and abundantly present, partly because of patronage by local rulers and, in north India until 1857, the Mughals. Moreover, elitist Indian musicians and musicologists generally believed in the scientific and spiritual superiority of Indian classical music over Western music. Particularly from the late nineteenth century, however, the Hindustani and Carnatic classical music traditions were increasingly institutionalized by those operating in a thriving public sphere, where they were often in dialogue with Western Orientalist and musicological works on Indian music, such as William Jones’s On the musical modes of the Hindus (1792), as well as books on the history of European music and musicology.Footnote 77

Three key modern Indian music reformers were A. M. Chinnaswami Mudaliar (d. 1901) in south India and Sourindro Mohun Tagore (1840–1914) and Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1860–1936) in the north. The Roman Catholic Mudaliar was trained in Western music and generally wanted to make ‘Hindu’ Carnatic music known to the rest of the world. In his Oriental music in European notation (1893) he notated a collection of south and north Indian melodies in staff notation and provided hints for harmonization. He was also one of the compilers of the encyclopaedia of Carnatic music, Sangita samprayada pradarsini (1904). Besides discussions of ragas (generalized melodic practices), performance routines, and biographies of musicians and authors of musicological treatises, this encyclopaedia includes numerous songs in staff notation with additional symbols to represent Carnatic music’s typical trills, shakes and slurs, and glissandi. From 1928, the Madras Music Academy was predominantly involved in the propagation of reformed Carnatic classical music. But while reformers came to see a specific singing style as the authentic representation of this tradition, they also adopted the Western violin, though in a retuned version and using a different playing technique, as the perfect accompanying instrument to the voice and as a sign of the modernity of Carnatic music.Footnote 78

Particularly interesting in terms of the reciprocity of the exchange of knowledge between Indian and Western scholars are the activities of Sourindro Mohun Tagore, who was an admirer of Mudaliar. As was typical of the times, his worldview was complex. He was loyal to the British crown but simultaneously an outspoken Hindu nationalist, who accepted the Western Orientalist notion that Hindustani music was in decay and dedicated his life to its revival. For Tagore, music became a central means to propagate the greatness of ‘Hindu’ civilization to the West. Proficient in both Indian and Western music, he founded the Bengal Academy of Music in 1881 and wrote numerous books on Indian music. In fact, his Universal history of music (1896) discusses music worldwide from a comparative perspective and with some measure of equality in the treatment of the different continents, not only examining each tradition against its own historical background but also paying attention to cultural interactions. In writing this book, he was influenced by Carl Engel’s The literature of national music (1879) and, in terms of organization, by Hubert Parry’s The evolution of the art of music (1893).Footnote 79

Tagore also influenced Western writers on music, with whom he often corresponded. Alexander John Ellis relied on his The musical scales of Hindus (1884) for his influential article ‘On the musical scales of various nations’ (1885), in which he challenged Western assumptions of natural tonal and harmonic laws, and indeed of cultural superiority. Von Hornbostel, Sachs, and other comparative musicologists ‘adopted the ancient Indian classification of musical instruments into strings, winds, self-vibrating instruments, and drums’ that continues to be used today.Footnote 80 Meanwhile, in his desire ‘to establish links in music culture between Indian traditions and music traditions in Western society’,Footnote 81 Tagore distributed his writings on Indian music as well as collections of Indian musical instruments, at his own cost, around the Western world, from Australia to the United States and Europe, including a presentation to the King of Belgium.Footnote 82

To this day, however, Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande remains the most important modern Indian music reformer. While he sought to revive and redefine ‘Hindu’ music, he simultaneously challenged the contemporary orthodox idea that the practice and theory of Hindustani music could be directly traced to ancient and medieval music theory treatises of a Hindu golden age in music.Footnote 83 Bhatkhande made his claims on the basis of extensive fieldwork conducted throughout the subcontinent. He collected an enormous amount of orally transmitted musical repertoire from contemporary performers from different lineages, which ultimately resulted in the six-volume Kramik pustak malika (1919–37), a collection of 1,800 compositions in Indian sargam notation. Between 1916 and 1926, he convened a series of All India Music Conferences. At these meetings, Hindu and Muslim scholars and musicians, from both north and south India, came together with the goal of determining the standards and boundaries of a national music for India.

Most significantly, Bhatkhande was the first to insist that ‘discrete notes are the basic stuff of music’.Footnote 84 Accordingly, he developed his that system of raga classification, which was in agreement with the south Indian theories that he had studied, for example, in Mudaliar’s Sangita samprayada pradarsini, but which he himself based upon the Western harmonium’s twelve notes.Footnote 85 In fact, the harmonium became the most widely used melodic instrument in South Asia, though it could not produce microtones or the subtle nuances of Indian vocal ornamentation. It became fully indigenized through some unique modifications, including the placing of bellows to the rear of the instrument so that it can be played while sitting, and special reed banks tuned for specific ragas. Also, among other features, its players use subtle ornaments and slurring that suggest melodic curves, variations in pump pressure to alter pitch, and, when accompanying singers, the exclusion of notes that are impossible to reproduce on a harmonium. As a result, this instrument played a role in the gradual decline in the use of microtones and the singer’s sense of intonation at large. Regardless, through his writings, his raga classification system, and his notation system in syllabic script, which generally replaced all other existing systems, Bhatkhande has been a major influence in the standardization of the teaching and performance of Hindustani music in India and elsewhere until the present day.

In the end, the music reforms of Mudaliar, Tagore, Bhatkhande, and others gave Indian classical music the respectability longed for by the developing and often English-educated Indian middle classes, who generally looked down on folk music, which they associated with tribal and low-caste groups and viewed in terms of a Western evolutionary perspective. Moreover, while north Indian music reformers generally referred to the authority of Sanskrit music theoretical treatises written during a supposedly pre-Islamic golden age of Hindu music, they ignored the fact that Hindustani classical music largely resulted from the interaction between the Indian and the Persian–Central Asian classical music traditions. They also undermined the authority of the majority of contemporary musicians, who were Muslims. Then again, in comparison to what happened in most other places in the world, music reforms in colonial India were the initiative of local elites, and the British colonial regime was hardly involved. At the same time, the Hindustani and Carnatic classical music traditions were propagated as national music through modern institutions, including All India Radio, especially in independent India after 1947. Recent research further shows that processes of classicization and musical nationalism over time also took place in regional non-elitist musical genres.Footnote 86

Music and nationalism in the New World: Brazil

The making of national music in Brazil took a different path from the countries previously discussed.Footnote 87 This was the New World and the traditional music that eventually became Brazilian national music was not based on indigenous/folk music but on Afro-Brazilian music that was connected to the history of slavery. Although Brazil had become an independent state in 1822, the musical focus of the country’s mainly white elite continued to be directed primarily towards Europe. Throughout the nineteenth century and no doubt partly because of state patronage, church music, opera, and chamber music were most popular, at least in cities such as Rio de Janeiro, Salvador da Bahia, and São Paulo. The situation changed somewhat towards the end of the century as the result of global political changes and intellectual interactions. In 1888, Brazil was the last country in the western hemisphere to abolish slavery; one year later, when it was declared a republic, Emperor Dom Pedro II and his family fled into exile in Europe. As to be expected, republican sentiments coincided with the emergence of national cultural consciousness. An interest in the country’s Afro-Brazilian music traditions soon grew and Brazilian composers increasingly appropriated hybrid Afro-Brazilian musical styles such as the lundu, the modinha, and especially the choro, in their classical compositions.

By the early twentieth century, a growing number of Brazilian intellectuals, who had previously viewed Afro-Brazilian culture negatively as a reason for the country’s perceived backwardness, began to promote racial hybridity as essentially Brazilian. In fact, Brazilian eugenicists and intellectuals defied European race science by arguing ‘that racial mixture was not the liability that scholars to the north insisted it to be and was instead a potential means for social and genetic improvement’.Footnote 88 Mário de Andrade (1893–1945), the poet and essayist who provided the philosophical and aesthetic foundation for what became known as the nationalist modernist movement in many artistic and literary fields, was trained as a musician and was crucial to the development of a Brazilian musicology. In his Essay on Brazilian music (1928), he specifically urged composers such as Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887–1959) to look for inspiration in Afro-Brazilian music instead of European art music. Likewise, in Cannibalist manifesto (1928), the poet Oswald de Andrade (1890–1954) adopted the modernist idea of primitivism and argued for the making of a uniquely Brazilian culture based upon the amalgamation of the country’s wide range of cultural traditions.

It should be emphasized, however, that these intellectuals simultaneously adhered to the evolutionist view of music history, from ‘primitive’ music to Western contemporary classical music. For them, authentic Afro-Brazilian music represented wild rhythms, sexuality, poverty, spirituality, and other caricatured depictions of Africa. In fact, many blacks and those with a mixed-race background also adhered to these stereotypes because, for them, Afro-Brazilian music more or less represented the authentic music of the contemporary ancestor. To a great extent, indeed, Brazilian paternalism and racism towards Afro-Brazilian music was part of a global uniformity that paralleled the attitudes of Western and non-Western scholars, composers, and musicians towards folk/non-Western music, including jazz in the United States.Footnote 89

Especially after the publication of Gilberto Freyre’s classic The masters and the slaves (1933), the emergence of a stereotype of the hybrid Brazilian as friendly, happy, and industrious reinforced the belief that samba was a musical exemplification of this spirit. All this accorded well with the populist objectives of the regime of Getúlio Vargas. The propaganda machines of the consecutive dictatorships of Vargas (1930–45) and of the military (1964–85) also promoted the popular music style of samba, rather than classical music inspired by Afro-Brazilian music, as Brazil’s authentic national music. The officially recognized samba schools received subsidies to make Carnival into a major tourist attraction. In 1939, the government made it obligatory for these schools to use nationalist themes for their parades and, under the influence of state censorship, samba composers also began to write lyrics about work ethics. As Marc Hertzman has recently emphasized, during this period there materialized ‘competing projects to define Brazil, its music, and its racial order’ that ‘shaped and often circumscribed’ the lives and careers of black musicians:

White writers, scholars, musicians, and critics’ attempts to order the past and present often linked up in surprising ways with more formal state-driven projects to control vagrancy, surveil black masculinity, and establish the desired economic order. Meanwhile, Afro-Brazilian musicians and intellectuals put forth their own categories and definitions, some of which lined up in surprising ways with those advanced by their white counterparts.Footnote 90

As samba was institutionalized and commodified as Brazil’s national music through the professionalization of musicians, recordings, copyrights, and the ever-expanding music industry, other musical styles outside the urban areas came to be identified as regional traditions. With the countercultural Tropicália movement of the late 1960s, which was partly inspired by Andrade’s 1928 manifesto, these marginalized musical styles were mixed with rock music, leading to what might be called a second wave of primitivist nationalism in Brazilian music.

While Cuba probably comes closest,Footnote 91 the situation in Brazil is clearly not iconic to all national music formations in Latin America. Even so, there are many similarities. Throughout the region, for example, nineteenth-century elites invented European military music, Italian-opera-inspired anthems, and classical music with vernacular references as national music. These musical genres continued to operate during the early twentieth century, but were overshadowed by popular national music traditions that were often propagated by authoritarian state regimes and/or through radio broadcasting and recordings. In Argentina and Mexico, these were based on folk music, respectively tango and ranchera (performed by mariachi groups), and thus represented another kind of primitivism from that in Brazil, though in Argentina the search for the authentic origins of tango, besides ‘gaucho culture’, partially led to Africa.Footnote 92 Unlike Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, local elites and/or governments in Peru and Columbia did not directly transform a regional folk music style into a national one.Footnote 93

Throughout Latin America, however, miscegenation came to be seen as something positive. In particular, the association between mixed-race identities and musical happiness became widespread as an identity marker that opposed white European civilization and progress. Despite these variations, over time national musical styles in Latin America experienced similar standardizing tendencies and became more or less institutionalized. They were also influenced by music genres from other regions or, indeed, countries, as national music traditions often interacted or competed with each other. In the process they produced new transnational products for an ever-growing global music market.

Conclusion

This article has emphasized that from the (late) nineteenth-century elitist non-Western music reformers grappled in numerous ways with a similar configuration of ideas and, accordingly, defined themselves as modern musical subjects in an emergent global public sphere. As the result of the proliferation of reinterpreted liberal and former Enlightenment ideas that was fed by intellectual networks shared between elites around the world, they increasingly envisaged their own music traditions hierarchically in comparison with Western music. Hence, these music traditions were not only rationalized and institutionalized as national musics in various ways, but also aestheticized, and came to be ‘understood as intrinsically meaningful rather than grounded in social context’.Footnote 94 To different degrees, these national music formations were supported by state power, especially in East Asia and Latin America, although very little in British India. They were also generally anti-imperial, and claims about the authenticity and spirituality of Asian, Arabic, or African music were meant to give strength to burgeoning national identities, exemplifying a global tendency to localize national culture in history. At the same time, these assertions by locals and Westerners alike often exoticized non-Western music, as for example in the case of the Theosophists’ veneration of the supposed spirituality of Indian and Javanese music.Footnote 95

In the context of the emerging discipline of comparative musicology, and like Enlightenment thinkers previously, non-Western music reformers became preoccupied with the origins of music, whereby the Japanese turned to India and the Chinese to the Tang dynasty, Persians to the pre-Islamic Sasanian period, Turks to Central Asia, Javanese to a pre-Islamic era of Hindu–Buddhist culture, Indians to a Hindu golden age, Brazilians and other Latin Americans to Africa, and so on. In Asia, and to a lesser extent the core Muslim world, this quest repeatedly led to nationalist beliefs of superiority in relation to the originality and antiquity of local high-cultural music traditions, with support often found in the work of European scholars. Conversely, the adoption of folk music in China, Turkey, and other countries largely paralleled what happened in Europe in terms of the search for the primitive and authentic musical spirit of the nation. Be that as it may, European categories of folk and art music, as seen in the light of an evolutionary view of music history, generally strengthened a similar divide in music cultures around the globe. Non-Western national music formations were directly related to power and status struggles in emerging public spheres and hence they repeatedly led to paternalistic, civilizing, if not discriminating, attitudes of elites towards the adherents and performers of ‘primitive’ folk or regional music traditions.

Bob van der Linden (PhD, University of Amsterdam, 2004), historian and musicologist, is the author of Moral languages from colonial Punjab (2008) and Music and empire in Britain and India (2013).