In 1542, the passage of the New Laws (Las Leyes Nuevas) prohibited the future enslavement of indigenous people called ‘Indios/Indias’ (Indians) in territories claimed by the Spanish. But the same clause abolishing the future bondage of Indios also specified that those slave owners who could prove legitimate possession could keep their property as slaves.Footnote 1 A spate of lawsuits in Castile ensued over the following decades as slaves and masters filed lawsuits and appeals before the tribunals of the Casa de la Contratación (House of Trade, located in Seville, and referred to throughout the text as the Casa) and the Council of the Indies (Madrid). Slave owners without just title attempted to prove that their property did not originate from a domain under the control of the king of Spain, but rather from Portuguese territories where, by law, captive Indios were still considered slaves. This was true even after the political unification of the Iberian peninsula in 1580. In 1570, King Sebastian declared that the Indians of Brazil (gentios) were, by their nature, free, but pressure from the Portuguese inhabitants of Brazil led to a ‘softer’ royal decree in 1573 that allowed Indio slavery to continue, except in cases of blatant abuse.Footnote 2 Of the several thousand Indio slaves who had been forced to go to Castile in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, 184 men, women, and children utilized their right as legal minors of the crown to litigate for their freedom between 1530 and 1585. Dozens of these litigants found it necessary to prove their imperial origins.Footnote 3

This article considers one of those lawsuits, initiated by the plaintiff Diego, between 1572 and 1575. Identified in Castilian court records as an Indio, Diego claimed to have been born in China, carried on a Spanish ship to New Spain, and eventually transferred to Seville. His master, the Portuguese cleric Juan de Morales, asserted that he had purchased Diego in Goa and taken him to Mozambique and to Lisbon before finally settling in Seville.Footnote 4 Rather than attempt to sort out fact from fiction, I probe deeply into Diego’s court case to show how and why the discursive tales told to court notaries by de-territorialized slaves such as Diego and other deponents helped to reconfigure imperial parameters.Footnote 5 I argue that the testimonies for the plaintiff (Diego) and defendant (Morales), to be analysed in greater detail below, illustrate contemporary notions of imperial connectedness and boundedness held by some of the most marginalized subjects in the early modern world: slaves. Even if the juridical, territorial, and sovereign borders of the Spanish and Portuguese domains were unclear, abstract, or untenable, litigants and witnesses deposing in the courtroom still maintained an idea of tangible empires.Footnote 6

Central to legal deliberations over the freedom of litigants such as Diego was the construct ‘Indio’. Over the course of the sixteenth century the use of this moniker in the Iberian legal context came to identify unknown and known peoples of both the East and West Indies: from China, the Moluccas, the Philippines, and Cochin or Calicut in India to Brazil, Hispaniola, New Spain, and Peru.Footnote 7 The vast geographic scope of the construct complicated litigation suits such as Diego’s since it was often difficult to prove who was an Indio from Spanish or Portuguese contested territories.Footnote 8 Moreover, given that foreigners from distinct parts of the globe resided in locales such as Seville and Madrid, it makes sense that a legal advocate in a Castilian court could just as easily label a man or woman from Guatemala as an Indio as he could someone from what is now mainland China or India. This combination of mobility and the enormous geographical and ethnic scope of the construct ‘Indio’ sometimes made it easier for litigants in Castile to argue that they were from a culture other than their own, since being a Spanish rather than Portuguese Indio was the key to achieving freedom. Thus witnesses testifying in the courts of law in Castile would claim that Diego belonged to either the Spanish or Portuguese imperial nación, which they conceptualized as a bounded demographic, legal, and geographic entity with certain privileges and responsibilities.

Given that much of the world, and especially China, could not easily be divided into clear Portuguese or Spanish domains, identifying the origins of Indios such as Diego in Castilian legal chambers posed a challenge for plaintiffs and defendants. But particular legalities also worked in favour of slave owners. The New Laws of 1542 may have defined Indios of Spanish territories as free by their nature, but declarations of just war against so-called resistant, bellicose, and barbarous peoples in prescribed territories and against designated peoples claimed by the Spanish and Portuguese continued to be sanctioned until the eighteenth century. In the Spanish territories, ethnicities considered enslavable between 1542 and the eighteenth century included the Chichimecas in northern New Spain, the Pijao in south-west Colombia, the Chiriguanos in north-east Bolivia, and the Araucanians in southern Chile, among others.Footnote 9 Captives, including men, women, and children were thus enslaved, branded, and moved to distant locations to be sold. Given these legal complexities, it made sense that witnesses would resort to arguments that Indios could be enslaved as captives of just war because they had resisted submission to Iberian (for which read: Christian) rule, or because enslavement based on just war practices occurring elsewhere in the globe validated its continuation in Spanish-claimed territories.Footnote 10 Additionally, despite Spanish royal decrees in the 1550s stating that slaves from other imperial domains (from the Indian subcontinent, or the Moluccas or Malacca, for instance) entering Spanish territories were to be freed, these individuals continued to be bought and sold by Spaniards, particularly in the Philippines after 1571.Footnote 11

To navigate these legal complexities and identify the imperial provenance of an Indio litigant such as Diego, witnesses might rely on the science of physiognomy, which determined one’s calidades (qualities) based on physical characteristics attributable to climate and proximity to the sun. Certain habitats were believed to harbour barbarous, therefore enslavable, people. Deponents might also qualify themselves as experts on things of the West and East Indies precisely for having travelled to or lived in some of the places they described.Footnote 12 Thus arguments based on just war in a prescribed territory, the confessional faith and physiognomic descriptions of the litigant, and direct experience in the Indies served as evidence that helped Castilian judges determine the imperial status of litigants such as Diego. One could argue that such rationales were carefully scripted to calculate a favourable outcome, but for our purposes what is important is how deponents used these criteria to demarcate the abstract geographical, political, and cultural parameters of imperial sovereignty.

Recent works have begun to take a global historical approach to slavery by showcasing how people in bondage traversed imperial borders and why they were identified as enslavable subjects.Footnote 13 This scholarship enhances our understanding of bondage and transcends those methodologies that consider hegemonic slave ‘systems’, analyse the ‘kinds’ of people being commodified (for instance, West Africans), or examine slavery according to typologies of labour regimes (plantation versus domestic slavery, for example). By integrating highly mobile slaves into a larger framework, the global approach also unfetters slaves from the yoke of fragmented ‘national’ historiographies that previously dominated characterizations of the peoples inhabiting the European, African, and North and South American continents.Footnote 14

Moreover, cases such as Diego’s embody the kind of ‘entangled’ history elaborated by the historian Eliga Gould and others, who suggest that imperial histories should focus instead on the mutual influencing and constituting of imperial subjects. Gould argues that comparisons tend to fix one empire or another and to take ‘the distinctiveness of their subjects as a given’.Footnote 15 Sensitive analyses of sixteenth-century chronicles, accounts (memoriales), maps, and other forms of inscription reveal the competitive yet fragile agendas of Spanish and Portuguese powers as they attempted to establish the parameters of possession and sovereignty in different entangled zones.Footnote 16 Furthermore, the contributions made by scholars in the fields of the history of science and the sociology of knowledge have taken the problem of how empires are constituted even further by arguing that the circulation and exchange of goods, people, and ideas tended to follow longstanding trade routes and the ocean currents rather than abstract imperial or ‘national’ demarcations. Such approaches displace the imperial ‘centres’ from their privileged position of constituting the grand narratives of colonial histories, which included the forced bondage of subjugated people.Footnote 17 Finally, global microhistorical analysis can illuminate how highly mobile individuals with deep, local knowledge transformed conceptualizations of empires, processes of identification, and confessional boundaries.Footnote 18

Cases such as Diego’s, therefore, should no longer be seen as outliers. Deciding whether an individual slave pertained to the Portuguese or Spanish domains was not a straightforward process, and witness depositions revealed the entangled nature of conflict, trade, territory, and sovereignty.Footnote 19 Moreover, Castilians, Portuguese, and men and women labelled in the Spanish courts as Indios were all trans-imperial subjects who regularly crossed permeable and sometimes imaginary imperial borders in evidence on the ships, in the ports, and on the streets of urban centres such as Seville and Lisbon, as well as in the homes of Iberians.Footnote 20 Borderlands were continually being traversed as slaves were sold to owners from different naciones, whether Flemish, German, Portuguese, or Castilian, some of whom followed the ocean currents. Yet, in the courtroom setting, deponents for the plaintiff Diego and for the defendant Morales articulated a clear sense of belonging to either the Portuguese or the Spanish nación. They did so despite the fact that they were highly mobile and trans-imperial subjects who regularly crossed imaginary and real geographic boundaries in parts of the world being contested by the Spanish or Portuguese. They might stress having interacted with Diego in a particular locale in America, Asia, or Africa, and then explain the ‘imperial’ routes they had taken with masters by sea or by land. Or, they might identify the litigant physiognomically and culturally as being ‘one’ with other imperial subjects, even if they had originated from places as distinct as Panama or China. As these deponents narrated the migratory pathways they had taken with masters, or explained their encounters with other slaves from other cultures in different locales, they imagined the parameters of the world in new ways.Footnote 21

Throughout Diego’s litigation suit and appeal, the stories that he and his former master told of his history of bondage spanned the globe from east to west and west to east. Diego claimed to have been born in China, carried on a Spanish ship to Nicaragua, and eventually transported to Seville, despite the fact that it was not until 1565 that Spanish navigators calculated a safe, reliable route from Acapulco to the Philippines – thirty to forty years after he claimed to have sailed east from China.Footnote 22 Morales, in contrast, asserted that he had bought Diego in Goa and had taken him west to Mozambique and to Lisbon before finally bringing him to Seville.

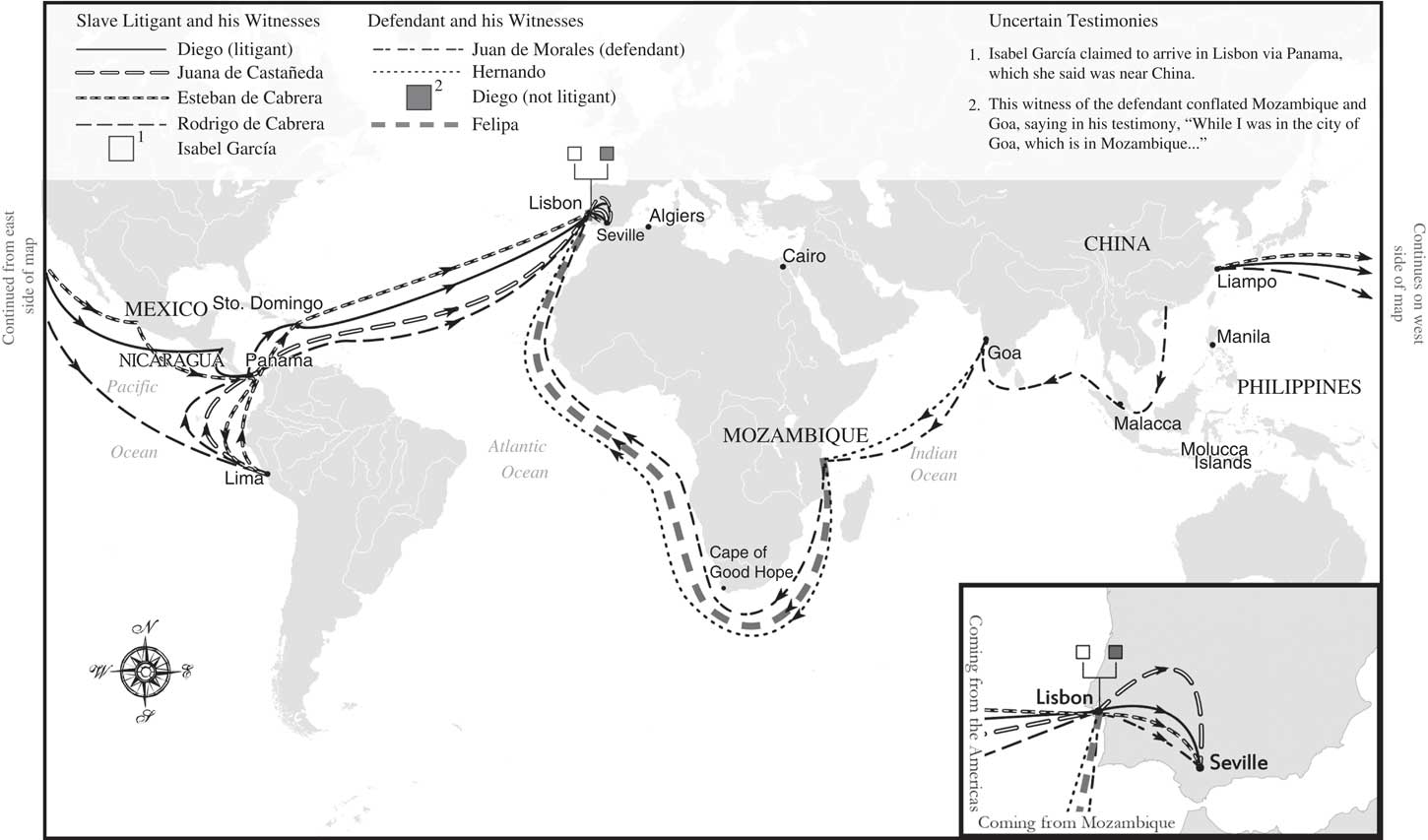

Over the course of three years, witnesses in support of plaintiff and defendant appeared twice to testify, and in doing so wove their own stories into Diego’s to reveal fantastic tales of migration. A few had travelled eastwards, as Diego claimed to have done, from China to New Spain, to Nicaragua, Peru, and Panama, and then towards Iberia (see Figure 1). Others had gone westwards on the path that Morales claimed was Diego’s, from China to Goa to Mozambique, Lisbon, and finally Seville. In the details of the depositions, we encounter a man freed in the royal inspection of Indio slaves conducted by the Castilian jurist Hernán Pérez in Seville in 1549, and a woman brought from Panama to Spain and later freed. We hear claims of a secret expedition of the interim governor of Nicaragua, Francisco de Castañeda, and the tale of a ship attacked by French pirates. We hear of slaves bartered in Portuguese Goa, and men and women eking out lives in Mozambique in a trading post long frequented by Arabs and Persians, where Portuguese ships now came and went. Many of the witnesses who told their stories had experienced servitude or slavery or knew someone who had, showing how deeply imbedded global slavery had become in the fabric of Iberian culture.

Figure 1 The Indio slave Diego’s possible journeys to Seville, as told to the Spanish courts by the litigant, defendant, and witnesses. Source: Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Justicia 928, no. 8, 1572–75. Map by Sarah Bell.

For three years Diego endured terrible suffering, including horrible labour conditions in chains, lengthy stays in prison, and threats. Ultimately, the sentence mandated by the appellate court of the Council of the Indies in July 1575 granted him his freedom. From this distance we will never know for certain Diego’s true place of origin or his cultural heritage. However, the litigation suit now catalogued as Justicia 928 tells us a great deal about global mobility and knowledge from the perspectives of former and current slaves, servants, and their masters from East and South Asia, East Africa, Iberia, and Spanish America who eventually converged in Castile.Footnote 23

Diego’s version

In giving his deposition on 10 November 1572 before licentiate Alejo Salgado Correa, the associate judge of the Casa, Diego declared that he was a natural (a term that denoted ‘belonging’) of the China of the Indies of His Majesty the King of Spain. He could not recall the names of his parents, but he still knew a little of his native language, although ‘there are only two or three Indios [in Seville] who understand, and only a little’.Footnote 24 His land was called Liampo, the Portuguese geographical referent to Ningbo in present-day Zhejiang Province. When Salgado asked whether it was an island, close to the sea, or inland, Diego seemed unsure, saying, ‘because I left when I was a child I do not remember much except that it was near the sea’. Next Salgado asked what animals could be found there, to which Diego answered, ‘there are cows, sheep [or, buffalo], goats, chickens, and there is a fruit called longuen [longan] and another called lachi [lychee]’.Footnote 25 In his land one could find a handful of Spaniards, he said, but no Portuguese. Asked how many years it had been since he came to Iberia, Diego said that ‘twenty-six years had passed since two or three ships of Governor Francisco de Castañeda had landed there’ (in China in 1546) and that he was six or seven years old when that had occurred. At the end of Castañeda’s stay, he had loaded a handful of Indios onto the ships, including Diego and a man named Esteban, who would later testify on behalf of Diego.

The judge asked where Diego went next. Diego was not certain, but he remembered being baptized in a church called Santa Marta and that one of Castañeda’s servants served as his godfather. It could have been in Nicaragua. After that he was put on a ship with around fifteen other Indios, but he could not name them. They went to Panama and Santo Domingo, and ‘there we got on the ship commanded by Captain Pedro Agustín and while at sea we were assaulted by French corsairs’.Footnote 26

The ship’s passengers were nearly dead of hunger when they put in at Lisbon. Diego was placed in the custody of a shoemaker named Juan Fernando and worked for him for a number of years. Then Diego met Morales, a cleric, who ‘told me that I would find many people from my homeland in Seville and that I should go with him there’.Footnote 27 Around 1565, Diego said, he accompanied Morales to Seville, where he dedicated himself to his trade as a shoemaker, giving Morales 5 reales from his weekly wages to ‘buy me some clothing’ to take back to his homeland. Diego continued:

When in 1572 Morales left for the Indies in the flotilla bound for Panama, he sold me to another cleric for 92 ducados, but I don’t remember his name. When I found out I was being sold, I filed a legal complaint before the ecclesiastical judge in Seville [because his master was a priest], and after Morales left for America I was placed in the custodianship of Rodrigo Alonso, a cloth merchant.

Diego concluded

I am not a slave and I only came with Morales [from Lisbon] because he offered to take me to China, and I came with him [to Seville] of my own free will. … I am free and I work my trade and give the extra [money] I earn to Morales to help pay the costs of food and dress for when I return to China.

When asked why he had not initiated a lawsuit for his freedom before, he answered, ‘I never thought I was a captive; it was only when Morales sold me that I presented a legal complaint for my freedom.’Footnote 28

What was imagined and what was real? Was this Diego’s story or someone else’s? Diego told a fantastic tale of travel from west to east and from one master to another that crossed oceans and vast continents, and that collapsed broad swathes of time. Like dozens of other slaves who litigated in the Castilian courts, Diego’s timeline of ‘bondage’ began with a benchmark episode – leaving Liampo – which constituted how all other events related to the legality of his enslavement would unfold. It was not clear, and never would be, whether Liampo was Spanish or Portuguese, but Diego framed his narrative in such a way that his ‘effective history’ about his origins emerged from this designated locale.Footnote 29 Since imperial place of origin or naturaleza (native habitat) was paramount to a successful outcome in his and other lawsuits, Diego’s legal advocate drew up interrogation questions that stressed that he was a Spanish Indio from ‘the province of China in the Indies of the Ocean Sea of His Majesty the King of Spain’.Footnote 30 His ‘origins’ helped to demarcate Diego’s sense of imperial belonging to a sovereign domain where Indios were free, and negated the fact that a Portuguese cleric claimed to have purchased him in Goa, considered Portuguese territory. Such an approach established that Diego’s deracination had occurred in a legal locus (Liampo, China), even though subsequently he had followed masters with different imperial affiliations from one site to another.

Calling himself an Indio, this trans-imperial boy encountered men and women from other locations and learned to survive in Spanish America, Lisbon, and Seville. The scope of his worldview was enormous; his de-territorialized experiences with other enslaved and free people were varied. Moreover, the disjunctions and circulations in time and space that he experienced made sense in the context of the expanding web of slavery and Spanish and Portuguese colonial rule. Both his fixed place of origin (Liampo) and his mobility from one locale to another throughout the Iberian Atlantic world established a clear sense of imperial belonging in a Castilian legal context. But it is in the telling of the tales of the witnesses who spoke on his behalf that other, equally compelling tales of mobility and belonging are revealed.

Witnesses on behalf of Diego

Once it became apparent that the priest Morales could influence the ruling of the ecclesiastical judge in Seville, Diego initiated a parallel lawsuit before the Casa in October 1572 on the grounds that he was an Indio and a vassal of the king of Spain, and that a secular court was the proper jurisdiction.Footnote 31 Two important deponents living in Seville spoke on Diego’s behalf: Juana de Castañeda, an India servant originally from Lima, Peru; and Esteban de Cabrera, originally from Liampo, China, and now married to Juana de Castañeda. As the notary began to record Juana’s deposition he noted that she was ‘the colour Indian’, forty years old, and presently living in a private home in the San Julián neighbourhood of Seville.Footnote 32 She began by saying: ‘I met Diego when he was a small child in Lima, but I do not remember anyone mentioning his place of origin (naturaleza).’ She went on: ‘Diego was among the Indians from China and Peru whom the governor Francisco de Castañeda sent to Spain. I was a young girl in the service of the governor, and followed his orders and accompanied the others to Spain.’ She told how the ship had been plundered by French corsairs, and how the passengers had disembarked in Lisbon, where ‘we were distributed to residents [and made] to serve them. [Months later] I came with Morales to Seville.’ She ended her deposition: ‘Diego is free, just as I, my husband [whom we assume was Esteban Cabrera, since she said he was also from the province of Poniente], and many other Indios who are naturales of the Indies of the province of the litigant are free.’Footnote 33

The second witness, the eighty-four-year-old Esteban Cabrera, identified himself as an ‘Indio from China’.Footnote 34 He explained that his place of origin was Liampo, in the provinces of New Spain. When asked how he knew Diego, Esteban responded, ‘I have known Diego since he was a small boy, more or less around six years old, while he was in the city of China in the Indies of His Majesty.’ How did he know for certain that Diego was from China? ‘I know for certain and without any doubt that Diego is from China because he does not understand any other language that is spoken to him and the language of the province of China is very different from those [languages] spoken in other parts and provinces of the Indies.’ Esteban added that he had heard someone tell the governor, Francisco de Castañeda, ‘that Diego was born and raised in China, which is where I am a natural as well’.Footnote 35 He continued:

The governor Castañeda sent a certain number of Indians from China and Peru to Spain to be placed in the care of Sancha de Castañeda, his mother. I was among those Indians, and I remember that Diego was also. We all came in the ship commanded by Captain Pero Agustín, and the French robbed the munitions, supplies, clothing, and other cargo from the ship. Diego was there as well. We were taken to Lisbon where we were divided up among residents there so they could dress and tend to us and get [labour] service from us.Footnote 36

Diego, he explained, was placed in the care of a shoemaker, who taught him his craft.

When I next saw Diego in Seville, he told me that Morales had promised to take him back to his homeland if he would accompany him to Seville. When Morales left for the Indies [in 1572], he sold Diego to another priest but he was then placed in the custody of Rodrigo Alonso, who placed an iron lock around his neck.Footnote 37

After Esteban had addressed the main questions, the head judge probed a little deeper. When had Esteban left China and who had brought him to Spain? Esteban answered that it had been around twenty-six years since the governor, Francisco de Castañeda, and two or three ships went to the seaport of Liampo. ‘After some days [Esteban could not remember how many], he returned to Spain, and Diego and I were on one of those ships.’ On the way the ships stopped in Mexico; because Esteban and Diego were placed in Castañeda’s service, they accompanied him to Nicaragua. The judge queried Esteban about Diego and his family. Esteban replied: ‘No, I did not know his parents because Diego was so young – only five or six years old – and I met him when he was in Castañeda’s house in Liampo.’ He could not say where Diego had been baptized. The judge then asked him about Liampo’s location in China. Esteban said, ‘Liampo is along the seacoast and it is not an island. From Liampo, which is land based, you can go inland toward other places.’Footnote 38

The viability of Juana’s and Esteban’s stories

The place that the Portuguese called Liampo was nestled at the delta where the Yang river (previously known as the Liampo river) emptied into the East China Sea.Footnote 39 For several decades, Chinese merchants (and pirates) who traded illegally with foreigners against the strict laws of the emperor had encouraged the Portuguese to trade in Liampo because there were no walled cities there. When word reached the emperor in 1549 that pillaging, robbery, rape, and murder had occurred at Liampo, he had a local magistrate dispatch a fleet to expel the Portuguese and permanently destroy the outpost. Eight years later, and in safer territory to the south, Macao began to serve as one of the main bases of operation for the Portuguese East Asian markets.Footnote 40

How Esteban Cabrera arrived in Mexico therefore remains a mystery. Any foothold that the Spaniards had in East Asia (following the debacle in the Moluccas in the 1520s and before settlements were established in Cebu (1565) and the Philippines (1570–71)) was precarious. He may have travelled from China to Mexico via Lisbon on a wayward (or illegal) Portuguese vessel, but he would never admit that in his testimony since any association with the Portuguese would discredit his account. The historian Juan Gil has found a will of Esteban Cabrera dated 1599, which states that he had travelled from his place of origin, Canton, to Portuguese Macao and from there to Iberia. But it gives no dates.Footnote 41 This trajectory would make sense, given the range of Iberian exploration in the 1540s, but it would be too dangerous to reveal in a Castilian court that he had travelled from east to west on a Portuguese vessel. Esteban probably calculated the dates of Castañeda’s supposed arrival in China to be around 1546, to allow the young Diego to be included among the mix of slaves. It is therefore doubtful that Esteban spent several months in New Spain with Castañeda, between 1531 and 1535.

The question is why Esteban even mentioned Castañeda, since the timing was off by several decades. Apparently the legal advocates did not check their facts. Castañeda had been trained as a lawyer and had held four posts in the Canary Islands and in Spain before assuming the interim post of governor of Nicaragua (1531–35) after the death of Pedrarías Dávila (Pedro Arias Dávila, 1468–1531).Footnote 42 The crown had appointed him because he had a reputation for being both scrupulous and trustworthy, neither of which turned out to be true. By 1535, Castañeda knew that he had behaved badly. To avoid paying for and participating in his required residencia (review of office), he left Nicaragua for Panama and Peru in June of that year with five ships laden with some 200 Spanish passengers and ‘more than 700 free male and female Indians’, some of them Maribios people from the coastal villages of Avangasta and Ybaltega.Footnote 43 If Esteban accompanied Castañeda in 1535 on his exodus, he would have been on one of these ships and he would have interacted with some of these men and women.

We have no direct evidence other than Juana de Castañeda’s testimony that Castañeda (who was never governor of Peru, as she claimed) paid a short visit to Lima where he ‘acquired’ her as part of his household. Juana said that she was the daughter of Juan Esteban and Catalina, who were indigenous and ‘naturales of the city of Lima’.Footnote 44 To have been placed at such a young age – perhaps four years old – under the guardianship of Castañeda might be an indication of orphaned status, a common plight of the time. Juana did not mention meeting her future husband, Esteban, at that point, but, if their stories are to be believed, the two somehow ended up together on the same ship bound for Spain that was later captured by French corsairs. She said, ‘Coming from Nombre de Dios, three French vessels fought against our ship until they broke the mast, and then they boarded the ship, robbed everything and abandoned it. The boatswain then disembarked in a port of Portugal.’Footnote 45 Juana’s version did accord with Castañeda’s journey in 1536 from Peru to Panama and then Santo Domingo, where his legal troubles caught up with him.Footnote 46 Moreover, even if the timing is off in some aspects of Esteban and Juana’s story, there was no reason for them to lie about being captured by French pirates, since pirates now regularly patrolled the Caribbean Sea.

But why did Esteban Cabrera and Juana Castañeda embed their tales in Diego’s? The three were certainly on intimate terms – Esteban being like a grandfather to Diego – and on several occasions the couple tried to extricate him from abusive situations. They were willing to testify on his behalf, and, like other Indios, to commit perjury if necessary. Quite possibly they mingled with other free and freed Indios in Seville, several of whom were from East Asia. There they could share legal knowledge and help others recover from the ravages of slavery.Footnote 47 Common experiences of being uprooted allowed them to establish a linkage – a form of diasporic kinship, if you will. Their oceanic trajectories and narratives of displacement were emplotted one within the other.

Perhaps, then, what is central to the construction of Diego’s global microhistory is not what happened in the 1530s but how Diego, Juana, and Esteban integrated their versions of the past into the present. The cognitive maps of East Asia circulating in Castile in the 1570s were very different from those of the 1530s.Footnote 48 Rooted in their stories was that of Francisco de Castañeda, who in their imagination had reached China, like the smattering of interpreters, Jesuits missionaries, members of other religious orders, and merchants arriving back in Iberia in the 1570s with reports and goods and ideas. A few of these recent returnees hoped to convince Philip II that he could use the newly established colony of Manila (founded in 1571) as a base from which to ‘conquer’ China and wrest it from Portuguese control.Footnote 49 In this context of heightened Iberian competitive interests in East Asia, it would make more sense for Esteban and Juana and Diego to connect the cis-Pacific areas of China, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Peru decades before advances in navigation made it feasible for ships to traverse those great distances and turbulent waters. Thus, despite the speciousness of their assertions – that prior to 1565 there existed a Castilian oceanic route from west to east – they felt comfortable saying so at a time when that had become a reality.

In the end, it does not really matter who was telling the truth. What matters is the fact that these intertwined, sweeping tales of personal, ‘local’ experiences told by Juana Castañeda and Esteban provide the reader with a sense of the vast mobility of peoples and the real connections of territories and cultures evidenced by the fact that individuals who had been to these places were now congregating in Castilian courts. Esteban’s tale of motion and movement even recalled the itineraries of European travellers and missionaries who would later record their global adventures for public and royal consumption.Footnote 50 It was now possible to collapse the past into the present and to tell these kinds of credible stories concatenating China with Nicaragua, Peru, and Lisbon. Like the European missionaries and travellers of the period, Diego, Esteban Cabrera, and Juana Castañeda were ‘globetrotters’ who strategically called themselves Indios because by the 1570s the construct was not only associated with freedom but with a broad notion of Spanish imperial governance.Footnote 51 Their deeply grounded experiences in different locales and their connections to other people and to Diego united the four parts of the world within their entwined life stories.Footnote 52

The other side of the story

In contrast, the stories told by the defence involved other circulatory flows of people and knowledge that followed entirely different ‘imperial’ pathways. The cleric Juan de Morales had stories from other parts of the world to weave into Diego’s past and other ways to configure his imperial Indio identity. In July 1572, when Morales told his version of events to the vicar general of Seville, he identified himself as a vecino (permanent resident or someone who ‘belongs’ to a locale) and natural of Laja, Portugal, and an educated cleric.Footnote 53 He said that he had bought Diego more than ten years before in Goa from a shoemaker named Diego Ramos, in exchange for an India slave and 47 pardaos (a form of currency pre-dating the Goa rupee) of gold. Like any responsible master, he had taught Diego how to pray. Although he acknowledged that Diego was now a professional shoemaker and a ‘man you could understand’ (hombre entendido, presumably that he was well spoken), he was still a captive slave and had always admitted to such. Besides, Morales continued, ‘many of the Indians from the Indies of Portugal are of the same nation as Diego, and many other castas de Indios are captives and obliged to serve’. From Goa the two travelled to Mozambique, the base of operations for the Portuguese trade to the east, where they remained for at least four years before journeying to Portugal and ultimately to Seville.Footnote 54 Morales complained that it was only after the two reached Seville that other Indios, Diego’s friends, persuaded him to press for his freedom. Diego had conjured the story that he was a natural of the provinces of China, ‘discovered by captains and soldiers of His Majesty as part of the conquest initiated by the Crown of Castile’. It was extremely daring of Diego to commit perjury before an ecclesiastical tribunal, Morales said accusingly, implying that he, a priest, was by his nature above such behaviour.Footnote 55

Morales further declared that, even if Diego were from China – slaves did arrive in Goa from East Asia – he would have come from Portuguese China.Footnote 56 The priest tried to make the geography clear for the judges: ‘Everyone knows that part of Asia is the domain of Portugal, not Spain. [Diego] is confusing the China that has recently been discovered in New Spain’ – here Morales was referring to the Philippines, which, after 1565, formed a part of the viceroyalty of New Spain – ‘there are about 1500 leagues of difference between one and the other.’Footnote 57 Morales was juxtaposing two very different ‘Chinas’ and conveying a knowledge of the connective routes from east to west, which presumably followed Portuguese and other, longstanding trade routes. He was also implying that slaves were regularly taken in just war by the Portuguese or traded by means of the well-established practice of rescate (ransom, exchange of goods, redemption), whereby slaves already taken by non-Europeans could legally be exchanged for goods by the Portuguese.Footnote 58

Three deponents on Morales’ behalf came from Mozambique and had travelled the carreira da Índia to Seville with different masters. The twenty-year-old Hernando, identified as black, said that he had known Morales for fifteen years and Diego, a ‘morisco’ (a forced convert from Islam to Christianity), for ten.Footnote 59 Hernando had accompanied Morales to Goa and had witnessed the sale transaction, noting the precise amount of money paid to a shoemaker named Ramos. Thus, in this instance, Diego’s ‘origin’ story had begun with legitimate sale in Goa, a long-established Portuguese imperial site. It is also interesting that Hernando marked Diego as a religious convert, perhaps to stigmatize him. A twenty-two-year-old witness, also named Diego and identified as moreno negro (the colour brown-black), had met Morales and Diego in Mozambique, which he described as being in the ‘Indies of the China of Portugal’.Footnote 60 He added that ‘the Indios who come from the Goa of Portugal of the casta de China, like Diego, are captives’, implying that he had been taken legitimately as a slave of just war.Footnote 61 He did not find it surprising that ‘Chinese’ Indios could be found in Goa and in Mozambique; unlike Hernando, the previous witness, he identified Diego as Chinese rather than morisco.

Another witness, twenty-three-year-old Felipa from Mozambique, identified as being ‘the colour black’, had seen Morales and Diego in Mozambique over the course of four years.Footnote 62 By ‘Mozambique’ the witness may have meant Sofala, a gold-trading centre located at an estuary, and the site of the original fortress built by the Portuguese in 1505. Diego may have spent time in this busy town making and repairing shoes for soldiers in the nearby Portuguese garrison. There he would have been surrounded by Arab, Gujarat, and African traders, and he and his master would have been dependent on the local population for meat, fish, and grains.Footnote 63 Given the international trade circuits of the Indian Ocean and beyond, the presence of the Chinese shoemaker Diego would not have been unusual.

Morales certainly presented a viable story, and the witnesses chosen to support him corroborated his version. Their depositions established a linkage between multiple points, including China, and the locales of Goa and Mozambique. As a priest from Ecija, his travels back and forth between Lisbon and Seville reselling cloth and other merchandise were nothing unusual. In fact, his trans-imperial pathway from Seville or Lisbon around the Cape of Good Hope to Mozambique and from there to Goa also made perfect commercial sense. The slave witnesses helped his cause because several had known him in Goa, Mozambique, Lisbon, and Seville, and it was perfectly plausible that their pathways as slaves would have also followed this well-established Portuguese trade route. That Diego was originally from China (a vague, homogenizing reference) may also have been true, since the Portuguese had been trading with the Chinese for decades, and Chinese junks had navigated Indian waters for centuries.Footnote 64 Galeote Pereira’s 1549 travel account commented on the existence of slavery in China, so a small traffic, mainly in female slaves, could have come from there to Goa.Footnote 65 Goa was home to Christians and Hindu Goans, people from Gujarat, and merchants from Malacca (known as a slave-trading centre) and places to the east. Slaves from the Moluccas, Mozambique, and elsewhere worked in Goa for the Portuguese soldiers, carried their masters in palanquins, and walked behind them with parasols to shade them from the intense sun.Footnote 66 It was also true that Chinese and other slaves from the Portuguese domains could be found in the homes of Sevillanos, and a few ‘Indios de casta chino’ (Indios of Chinese ancestry) accompanied Castilians westwards across the Atlantic.Footnote 67

Nonetheless, just as Esteban, Juana, and Diego probably conspired to intertwine their stories, the witnesses on behalf of Morales are likely to have done the same. They might have been induced (or paid) to say that they had seen Diego in Mozambique or Goa. Furthermore, just as Esteban, Juana, and Diego linked the locales of Liampo with Mexico, Panama, and Nicaragua, the witnesses who spoke on behalf of Morales conflated Goa and Mozambique as being a part of the same empire. Other deponents drew on imperial and local understandings of descriptors by claiming that the litigant Diego was at once a morisco and an Indio of the Chinese casta. The possible ways of configuring Diego were nearly limitless.

What is apparent from the depositions for plaintiff and defendant is how different places and activities were connected in their minds. It was not odd to associate Goa with Mozambique, or to say that there were people of different confessional faiths and Chinese Indios in Goa, just as it was not strange to integrate the lands and peoples of Asia and the Americas into one story.Footnote 68 Deponents could concatenate the different locales into a tale about mobility and belonging. Both Morales’ and Diego’s slave deponents had passed through different cities, only to be uprooted and taken to the next colonial entrepôt. The itinerant pathways described by slaves and masters reiterated the idea that locales such as Goa or Lima demarcated imperial realms through movement and the connection of one place to another. These sites were constituted by mobile individuals as bounded within imperial domains, because the movement to and from those locales formed a part of the larger cultural imaginary of what constituted an empire.Footnote 69 The idea that Diego could come from any of these entangled, trans-imperial zones (and the locales that constituted them) is what is so captivating about his case. It is also illustrative of just how spatially transcendent and de-territorialized the term ‘Indio’ had become.

When comparing empires for the purpose of identifying Indio slaves, deponents articulated their movement across and within imaginary ‘borders’. Their legal narratives revealed an expanding sense of distance and geographical parameters that assumed a moving point of view and an open-ended connectedness between locales scattered across the globe. Moreover, in the process of assembling and concatenating evidence from the different depositions into a legal defence, a new ‘space’ of knowledge was created. Imagining both the connections between different localities (China with Goa and Mozambique or Liampo, Nicaragua, Lima, and Seville) and mobility from one locality to another helped produce an understanding of what it meant to belong to an ‘empire’.Footnote 70 Slaves and former slaves who embodied those locales, and who knew the sights and sounds and smells of different environments, were integral to that process. Not only did they conceptualize space as physical environments that were being contested and demarcated by the Portuguese and Spanish, but they also conceptualized it as a continuum of movement, and as an epistemological possibility of how places such as Lima or Goa might be traversed or inhabited. These new conceptualizations of space, place, and belonging were then inscribed onto parchment by a court scribe who joined together the different narrative accounts into the same document, thus giving a global Indio named Diego a physical, legible form.

The stitched-together folios which ultimately comprised the litigation suit also contained the diasporic tales told by trans-imperial Indios who were re-conceptualizing the early modern world in previously unfathomable ways. The central ‘plot’ of Diego’s purported journey served as a backdrop for the migratory tales of other colonial subjects from vastly different locations, spanning four decades. Their global migrations and the possibilities of following global pathways converged in representations of the Chinese Indio Diego and the possible lives that he had lived. These concatenated depositions linked unusual sites (Liampo with Lima), collapsed vast distances (Acapulco to China, or Goa to Mozambique, for instance), and expanded the spaces that Indios could occupy. Justicia 928 connected east to west and west to east, thus uniting the ‘four parts of the world’ and the continents of Asia, Africa, Europe, and America.Footnote 71

Switching tactics

Sometime in 1573 the Casa rendered a sentence in favour of Morales. Diego immediately appealed the decision before the Council of the Indies, but by then his circumstances had changed. Morales had since departed for America, and Diego was under the guardianship of a cruel new caretaker, Rodrigo Alonso.Footnote 72 Nearly a year later, in May 1574, the Council of the Indies determined that the case should go forward and that a secular court had the proper jurisdiction over Diego’s case, since he was presently in Alonso’s custody. The case now involved Diego as the plaintiff and Alonso as the defendant, and the court issued a summons for Diego to appear in court in Madrid.Footnote 73

The Council began interrogating witnesses in 1575 and the questions asked by Nicolás López de Sarria, the prosecuting attorney, had a decidedly ‘imperial’, comparative, and abstract tone.Footnote 74 After decades of dealing with appeals initiated by masters or Indio slaves in Castile, the Council had honed its repertoire of legal strategies.Footnote 75 As the jurisdictional and legislative body that oversaw all matters related to the Spanish Indies, it and its judges would have taken a keen interest in Diego’s case. The outcome might help determine the parameters of sovereignty in East Asia at a time when competition with the Portuguese in that part of the world was on the increase. More was at stake than the freedom of one man.

Since the 1540s, judges at the Council had based their legal renderings about the freedom of Indios on stylized characterizations about certain imperial peoples, including whether they were peaceful or bellicose (for which, read ‘enslavable’). True to form, López de Sarria asked witnesses to comment on Diego being from Castilian China based upon his physiognomy, including the shape of his face and head, and on his gestures.Footnote 76 Moreover, the attorney encouraged deponents with experience in the Indies – especially anyone ‘who had been in that province [China] or others of the Indies and Tierra Firme’ (a general reference to the continent of South America) – to comment on what distinguished Diego from the Indios of Portuguese China.Footnote 77 This line of questioning established an imperial connection between non-specific land masses and the ‘imperial’ attributes of their inhabitants. Council members could now call upon travellers, and other ‘experts’, including Chinese residents in Seville who had a deeper knowledge of the area, to testify.

The ‘Chinese’ Esteban Cabrera did not testify again in 1575, but his wife, Juana Castañeda, did, essentially reiterating what she had said three years earlier. A man named Rodrigo de Cabrera also spoke. He did not state his relationship to Esteban Cabrera (perhaps he was a son), only that he was forty-seven and an oil maker and that he had been born in Liampo. If this were true, Rodrigo could have travelled with his father, Esteban, as a small boy. Maintaining that he had travelled from west to east, he, too, repeated the story of Governor Francisco de Castañeda coming to Liampo around 1546. Rodrigo claimed to have served Castañeda in China and then accompanied his new master to Lima and then across the Atlantic on the vessel captured by the French.

But the tone of two other witness accounts was decidedly different, and underscored the imperial qualities of the litigant, Diego. On 7 February 1575, Francisco Díaz, a forty-five-year-old Indio who claimed to be from the ‘provinces of China of the Indies of the Ocean Sea’, a tailor and permanent resident of Seville, said that he had known Diego for seven years. He was absolutely certain that Diego was from a place called Liampo in the domain of Philip II, the current king of Castile: ‘I have always treated him as such and have spoken and speak to him in the natural language of that province’. He mentioned talking with Diego about signs and things that were specific to the culture of Liampo, ‘which this witness knows is true because I am someone who was raised in the said place’. Diego’s countenance, physiognomy, quality, manner, and colour resembled the people of that area. Díaz stated, ‘I know that the Indios from China are free because I heard it being said and I came from China over thirty years ago [in 1545]’.Footnote 78

The next witness, Isabel García, was an India who had been freed by authorities in the Casa.Footnote 79 Now fifty years old, a natural of Panama and wife of Juan Hernández, a labourer in Seville, she stated that she had known Diego for five years. She was certain that he was from China, ‘because it is near the province of Panama and the Indios from these two parts are of one nation and language’.Footnote 80 They had spoken together, and he had the same way of speaking as the Indios of the province of Panama. Facially, they were ‘of the same countenance’.Footnote 81

Whether López de Sarria counselled Diego to choose Francisco Díaz and Isabel García as expert witnesses we will never know. These two deponents were authoritatively able to answer the questions of the interrogatory based on their experiences in the Spanish Indies, whether China or Tierra Firme. From our historical vantage, assuming that Panama and China were one nation and in proximity seems very odd. But in the context of proving imperial fixity in the 1570s, García’s deposition makes sense. As Diego’s case and similar litigation suits show, arguing for imperial oneness was not unusual, and including China in the ever-expanding dream of Spanish possession and sovereignty in the westernmost part of the West Indies made strategic sense.

Rodrigo Alonso’s defence followed in much the same vein as the plaintiff’s depositions, but revealed new information. As an expert in things of the Indies and Diego’s new master, he had known the plaintiff for three years and did not take Diego to be a natural of China. He based that assertion on having lived in Seville, an international city known to contemporaries as ‘the endless globe’, and having spent time in Peru in Lima and Quito and in other parts of the Kingdom of Granada and Tierra Firme over the course of ten years.Footnote 82 ‘I have seen many Indios of the province of China of His Majesty’, he stated, ‘and they are different in their appearance, face, and way of being from Diego.’ He could not say with any certainty where Diego was from but knew that he had served Morales, who had left him languishing in the archbishopric prison. More importantly, Morales had never sold Diego to anyone else, nor was he Alonso’s slave. Thus Alonso had no dominion over him; he was only the guarantor of Morales’ debts when he left for America. The instructions were to look after Diego and to ensure that he was not branded, taken away, or mistreated. Alonso emphasized that Diego was under his protection but that did not mean that he, Alonso, should be the one facing the judges of the Council of the Indies. That was Morales’ responsibility.Footnote 83 However, Morales was in Peru and had no intention of returning, although he managed to send instructions to Cristóbal Pérez, a lawyer representing him.Footnote 84

In the meantime, it was thought that the sentencing in another case pending before the Council of the Indies might have positive consequences for Diego’s suit. It involved a famous Portuguese slave trader, Manuel Caldera, who served as the financial officer for the queen of Portugal, and a slave named Felipa Sosa, who was currently in his legal custody in Madrid.Footnote 85 Felipa argued that she was from the Rio de la Plata area, but Cabrera said that she was from the China of the King of Portugal. Cabrera was not her owner, he said, but overseeing her care – another similarity to Diego’s case. Because her slave owner, a Spanish doctor, was nowhere to be found, the Council held Cabrera responsible for Felipa. Cabrera tried to skirt this argument (as did Morales) by arguing that there was no doubt that Felipa came from Portuguese China; the Chinese were ferocious and bellicose people who would not allow Europeans to intrude, which is why the Portuguese built so many fortresses in the area and captured so many Chinese as slaves of just war.Footnote 86 In May 1575 Felipa was declared free from bondage, and Caldera was ordered to remunerate her years of labour in wages. The case established a legal precedent determining that whoever had legal custody of a slave in the owner’s stead could be tried if the owner was not available.

The sentence rendered in Felipa’s lawsuit had important implications for Diego’s, but it also reveals that the standard argument that bellicose people from certain territories could be declared to be slaves of just war was now being used to categorize the people of China. This carte blanche logic about originating from a just war domain was also used in Diego’s case, but in a slightly different way. While Morales’ lawyer, Cristóbal Pérez, objected to Felipa’s case serving as a precedent, he also issued a new allegation that had never been raised before: that Diego was from the China of the Portuguese domains and that those Indios, because of their warlike nature and resistance to Christianity, were slaves, ‘like all the blacks from Cabo Verde, Guinea and other provinces who are brought as slaves to Portugal and then sold in Castile’.Footnote 87 Once again, we see an attempt to collapse (and connect) the bellicose peoples of diverse landscapes, where intermittent conflict not war was the norm, into a uniform ideal about legal subjugation and enslavement under Portuguese rule. Further, if the vassals of the king of Portugal had the right to maintain slaves from the provinces of China, it was the same for persons who sold or ceded them to someone else, even if they were ‘Castilians, Valencians, Aragonese, Italians, or from whatever nation the buyers come from’.Footnote 88 Pérez added that the Indios from the China of Portugal were very different in their gestures and language from the Indios of the other Indies, as was well known in Seville. If linguistic experts were called in (and there were Chinese to be found in Castile), he asserted, they would be able to pinpoint Diego’s place of origin. Above all, the case should not be reviewed in a Castilian court because Diego remained under the legal jurisdiction of the laws of Portugal.Footnote 89

This last effort to differentiate between Portuguese and Castilian Chinese and to argue that place of origin of the slave litigant held sway despite the imperial affiliation of the current master did not work. The Council of Indies pronounced a definitive sentence on 15 July 1575 stating that Diego had proven his case, and that Rodrigo Alonso should not abscond with the clothing he had given Diego to replace the salary that the court had determined his former master now owed him.

Conclusions

Diego’s case began in 1572, just seven years after the Spanish had established a foothold in the Philippines. By then the imperial frontier zones had expanded to the South China Sea and the western Pacific, making the question of the imperial identity of ‘Chinese’ slaves from mainland China and the Philippines more difficult to prove in the Spanish courts. However, Esteban and Rodrigo Cabrera and other Chinese slaves had been present in Seville at a much earlier date, pointing to a small traffic in human merchandise via the Portuguese from east to west. Esteban Cabrera may have travelled from Portugal to Mexico, although such instances were uncommon at that time. After 1565, when navigating the currents became easier, slaves from the Philippines and elsewhere, labelled as chinos, began arriving in Mexico, at first in small numbers and then in larger ones.Footnote 90

Whether the journeys that Diego’s witnesses described were fabricated or partially true, they linked time and space in new ways. Stories such as Diego’s reveal the scope of broader Atlantic and Pacific exchanges, which included not only spices, cloth, seeds, and plants but human beings usurped illegally from their homelands in significant numbers.Footnote 91 The four parts of the world were connected not only on maps, in discussions of political strategy, in calculations made by astrolabes, or by following the stars, but in the conversations and diasporic tales told by Indios who converged in Seville and Madrid and who told their circumscribed stories to court notaries.Footnote 92 Thus Juana de Castañeda, an India from Peru, could embed the story of her Atlantic crossing into Esteban Cabrera’s imaginary travels from Liampo to Nicaragua and beyond.

The braided tales told by deponents make sense because of what they tell us about how mobility informed processes of identification at a time when Portuguese and Castilians vassals were also constituting themselves in more bounded ways for strategic reasons. By linking so-called imperial sites, deponents concatenated diverse places such as China, Goa, Mozambique, Lisbon, and Seville into their tales of displacement, creating new spatial forms of knowledge. We see witnesses and litigants grappling with the geographic and cultural configurations of the globe in the bold assertions that many Portuguese Indios were slaves, that all bellicose peoples under Portuguese authority should be treated as captives of just war, or that the territories of East Asia belonged to the Portuguese. That the India Isabel García could claim that the people of Panama and China were one is far from outlandish.

To a greater or lesser extent, each deposition refracted the imaginary landscape that Diego had supposedly travelled. These interlaced narratives encompassed experiences of belonging and journeys embedded into an endless global Diego: a Chinese, but omnipresent Indio slave who had followed the charted courses of navigable seas. In the process, the deponents transformed the real and imagined notions of the broader world into an interconnected landscape with new circulations and disjunctions and comparative notions of imperial alterity. They also relied on circulating notions of imperial fixity and boundedness to constitute themselves as Indios.

Diego’s strategic identification as a Chinese Indio is illustrative of how Castilians and Portuguese subjects comprehended and made sense of the world. We see demonstrations of legal theatre as each deposition followed individual geographic pathways to determine the kind of Indio Diego was. Witnesses from different parts of the globe attempted to prove both intimate and reliable affiliations with the plaintiff or the defendant. Not only did they reveal their fantasies about Portuguese or Spanish landscapes, but they embedded their own diasporic tales of liminality and loss in Diego’s. Here we have the ultimate example of the Indio experience in Castile: an attempt to affix boundaries to a construct that was, in itself, a metaphor for how the larger, and rapidly changing globe was imagined and lived. ‘Indio’ had become a symbol for someone who was free, not enslaved, and someone from China, called chino under certain circumstances, would want to ascribe the fixed identity of Indio to him- or herself. Their identities as Indios were no longer spatially bound or culturally homogeneous, but rather trans-imperially present in the imaginations of those whose own ‘local’ experiences – in Liampo, Peru, Goa, Seville, or Mozambique – were mirrored in Diego’s. But the construct ‘Indio’ was also symptomatic of the tensions between imperial regimes’ desire to constitute and reify themselves as bounded entities, and of the global mobilities that informed those processes. Thus it is in the power to imagine Diego’s ‘lives’ that we see the realisms of the larger-scale temporal and spatial perspectives of Iberian colonialisms, more globally comprehensive than anything previously conceived.Footnote 93

Nancy E. van Deusen is Professor of History at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario. She is the author of three books, most recently Global Indios: the indigenous struggle for justice in sixteenth-century Spain (Duke University Press, 2015).