When it comes to their craft, historians are paradoxically prone to amnesia. The new ‘world’ history was born in the 1960s, the brainchild of William McNeill and his Rise of the West, and institutionalized in the 1980s with the founding of the World History Association and the Journal of World History. It defined itself by emphasizing a double break: from national history, on the one hand, and from the old ‘universal’ history of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, on the other.Footnote 1 Then came ‘global’ history, the distinctive product of the globalization process triggered in the 1990s by the fall of the Soviet Union.Footnote 2 This linear genealogy, however, has come under scrutiny. The distinction between world and global history has been repeatedly downplayed, while some have suggested that today’s global history may go back to the nineteenth century, or even as far as the sixteenth.Footnote 3

Among the works usually given short shrift in streamlined genealogies of world /global history is the UNESCO History of mankind. Initiated in the early 1950s and published in six volumes between 1963 and 1976, this massive collective venture was the work of the International Commission for a History of the Scientific and Cultural Development of Mankind, and of the several hundred collaborators from all over the world whose output it coordinated. It has, until recently, either been ignored altogether or been scoffed at as a doomed enterprise of politically correct history.Footnote 4 In the first issue of the Journal of World History, published in 1990, Gilbert Allardyce included Louis Gottschalk’s experience editing the fourth volume of the History of mankind in his genealogy of world history. He concluded, however, that the UNESCO project, too profoundly embedded in the idea of promoting ‘international understanding’, was basically ‘cant’ – a counter-model to be avoided.Footnote 5 This negative image has already been partly modified by Poul Duedahl, who considers the UNESCO project to be less relevant for its ‘concrete achievement’ than for the ‘process’ it laid bare. It is this process, he argues, that was ‘groundbreaking … as the first trial of nationalism and Eurocentrism after World War II’ and the ‘starting point of the postwar trend of writing global history’.Footnote 6

To raise interest in the History of mankind while the volumes were being written, the Commission had decided upon the publication of a scholarly journal, which was also to serve as a kind of testing ground. The first issue, published in July 1953, ‘under the auspices and with the financial assistance of UNESCO’, bore a triple title: Cahiers d’Histoire Mondiale / Journal of World History / Cuadernos de Historia Mundial. It was placed under the editorship of the celebrated Lucien Febvre. As the co-founder in 1929 of the Annales journal, Febvre ruled the French historical establishment from his position at the Collège de France, and was involved with UNESCO at an early stage. Over the years, an impressive list of important historians contributed articles: among others, Bernard Lewis, Marshall G. S. Hodgson, Robert R. Palmer, Pierre Chaunu, Charles Gibson, Shelomo D. Goitein, and Sidney W. Mintz. In spite of these prestigious names, the first Journal of World History, which is mentioned only in passing in recent literature on the UNESCO project, has until now attracted little scholarly attention.

This article therefore advocates a shift in focus, from the History of mankind to the Cahiers d’Histoire Mondiale.Footnote 7 Although the two ventures were, as we shall see, intimately related, one may wonder whether the medium of the scholarly journal was not more suited to world history as an intellectual project. Marshall Hodgson, for one, confessed that the paragraphs he had contributed to volume 4 of the History of mankind had had ‘to conform to a general outline which had unavoidably been drawn up from the perspective of local Western history’. By contrast, he felt that he had been more at liberty in the columns of the Cahiers to ‘fully embody’ his approach, placing Islam at the centre of world history. Publishing in the Cahiers also offered him the chance to ‘make some suggestions for the general historian’.Footnote 8

A scholarly journal may be likened to what the sociologist Bruno Latour calls a ‘black box’, namely something familiar that produces an ‘output’, but whose inner workings we do not see. As professional historians, we all read journals, and some of us even participate in their production. Yet there is surprisingly little literature on how their functioning may decisively shape the production of historical knowledge. This may be due to the fact that historiography is studied mainly as historiographic content, through the lens of intellectual history. It might also be because many significant journals of the past are still alive today, their archives unreleased.

The Cahiers was not a typical journal, embedded as it was in the UNESCO machine. Yet, this is precisely why it is now possible, thanks to the rich material in the UNESCO archives, to peep into what Lucien Febvre called his ‘kitchen’, the rather messy cook-room of world history. This insider’s view is further facilitated by the private papers of the French economic historian François Crouzet. Initially Febvre’s assistant, Crouzet took charge of the editorship, along with the Swiss historian Guy S. Métraux (the brother of the famed anthropologist and UNESCO stalwart Alfred Métraux), upon Febvre’s death in 1956.Footnote 9 Together, these documents afford the rare opportunity of peering over the shoulders of the editors of the Cahiers as they struggled to carve out a place for themselves amid the power struggles within the editorial committee; as they circulated the material and produced the journal on a daily basis; as they adjusted to the shifting global politics of the Cold War and the first wave of decolonization; and as they defended its existence and tried to ‘enrol allies’ for the world history paradigm among academia and the wider public the world over. Thus, one gets a feeling of history in the making, of world history not only as an intellectual project but as a practice.

The end product of this activity was the fourteen volumes, comprising a total of 625 articles, published from 1953 to 1972. To try to make sense of this huge amount of material and ascertain whether the journal was successful in its aim of diversifying its authorship and content beyond a Eurocentric perspective, two databases were created. The first lists the 550 authors of the articles, focusing on their institutional affiliation. The second tabulates the articles themselves, by tagging their content according to place, time, theme, and methodology. A series of key articles were also read and studied in detail.

The picture that emerges from this combination of distant and close reading is twofold. On the one hand, it shows that the editors’ persistent efforts to overcome Eurocentrism, as they worked with a dual definition of world history both as the result of worldwide collaboration and as a comprehensive history of the world, met with a somewhat mitigated success. On the other, it will demonstrate that the distinctive contribution of the editors of the Cahiers was a reflexive understanding of the journal as both a forum where the very definition of world history was an object of debate, and a laboratory that experimented with new forms of relational history. Indeed, beyond the recovery of a lost genealogical moment, this article ultimately contends that today’s epistemological discussion on the nature of global history can benefit from the reflection offered by this forgotten experiment. Despite all that separates the international humanism still steeped in the dregs of empire that gave birth to UNESCO and the postcolonial world of 2019, what the world history of the 1950s and 1960s and the global history of today have in common is the project of ‘going beyond the West and the rest divide’ (to quote from the Journal of Global History’s mission statement), and the problem of devising the means to realize it.Footnote 10

The struggle for autonomy

In the first issue of the Cahiers d’Histoire Mondiale, in a brief ‘foreword’, Febvre, as the editor, introduced the new journal. ‘History is not war,’ he wrote, ‘a series of intrigues and criminal tricks, aggressions and furies of devastation, cynical campaigns of pillage and conquest conducted by Kings, Emperors, Dictators, men of prey leading bloody armies to the spoils.’Footnote 11 Rather, he proclaimed that history ‘is peace’. The rejection of political history as a sequence of events fashioned by great men, central to the Annales agenda as it had been defined by Febvre along with Marc Bloch in the early 1930s, acquired a new meaning in the context of the UNESCO project. Since nationalist history had led to the carnage of two world wars, a new history was needed, one whose mission was to foster peace between nations, one that would consider them all, ‘great’ or ‘small’, ‘as so many participants in a great common enterprise …, all taking away from one another, or giving or borrowing, their achievements – returning them sooner or later, modified, transformed, perfected, no longer particular but universal’.Footnote 12

The writing of a ‘history of mankind’ stressing scientific and cultural interchange was first suggested by Joseph Needham to the first director-general of the newly founded UNESCO, Julian S. Huxley, in March 1946. The project was approved by the General Conference in 1947, but conceiving a workable plan proved difficult.Footnote 13 In May 1948, Huxley presented his plan, which Febvre considered Eurocentric and evolutionist. One year later, he produced a counter-plan, which stressed exchanges and borrowings between peoples.Footnote 14 The ‘academic cockfight between Huxley and Febvre’ continued for some time,Footnote 15 until December 1950, when Ralph E. Turner took the first meeting of the new International Commission for the Writing of the History of the Scientific and Cultural Development of Mankind in Paris by storm. A professor at Yale, Turner had demonstrated his aptitude for world history with his imposing two-volume The great cultural traditions, a sweeping synthesis on the ancient civilizations from ancient Greece to the Far East published in 1941, which a reviewer had compared favourably to the works of Spengler and Toynbee for information and scope.Footnote 16 Not only did Turner manage to impose a compromise solution for the History of mankind plan, but he was also appointed chairman of the editorial committee. It was at this point that it was decided to create the Cahiers d’Histoire Mondiale. Its editorship was granted to Febvre as a kind of compensation, since his plan had not been adopted.Footnote 17 The journal was conceived as a testing ground for the History of mankind, its somewhat paradoxical mission being to allow the material to ‘ripen’ without delaying the volumes’ publication.Footnote 18

Febvre’s ambiguous position, at once in and out, explains why he penned another intervention in this first issue, this time in the ‘Critiques et suggestions’ section, where he explained his ‘paradoxical’ role as editor. He wrote that ‘the editor of the Journal looks like a chef who is required to prepare meals, four great meals a year, as delicate, as well-composed, and at the same time as economical as possible, without having the say as to the buying of the food, nor even as to the menu’.Footnote 19 By this he meant that he was not able to commission articles, since that was the task of the author-editors of each volume of the History of mankind and of the members of the Commission. His job was simply, as he put it, to ‘arrange … rationally’ the material thus provided. Having been at the helm of the Annales for more than twenty years, Febvre was not satisfied with this subaltern position. He launched into a ten-page devastating and comprehensive criticism of the way in which the Cahiers functioned.Footnote 20 His dissatisfactions were numerous: the authors’ nationality, the financial situation, the length of the articles, and even their content, which he considered leant towards an ‘integral history of the world’, too political and too comprehensive, as opposed to a history more strictly focused on science and culture.

When Paulo Carneiro, the Brazilian president of the Commission, read Febvre’s text, he was surprised, to put it mildly. Although acknowledging that Febvre was right on a number of issues, he feared for the whole project’s credibility should internal struggles be vented to the public: ‘whatever happens in the kitchen is solely the “chef’s”, his aides’, and the host’s business’, he explained to Febvre, who was thus censored. ‘The editor’s role’ in its published version is a two-page watered-down text.Footnote 21 Febvre, who reacted relatively graciously at first,Footnote 22 had his revenge a few months later in the columns of the Annales, where he referred to the UNESCO project quite disparagingly. In a mischievous footnote, he distanced himself from the ‘[UNESCO] World history’ and let it be known that he had agreed to head the Cahiers in ‘quite peculiar circumstances’. He even went so far as to imply that the journal’s function was to provide material for ‘a valid Histoire du monde’, the subtle change of language suggesting a counter-project, which was in fact the ‘Destins du monde’ collection of books edited by himself and Fernand Braudel.Footnote 23

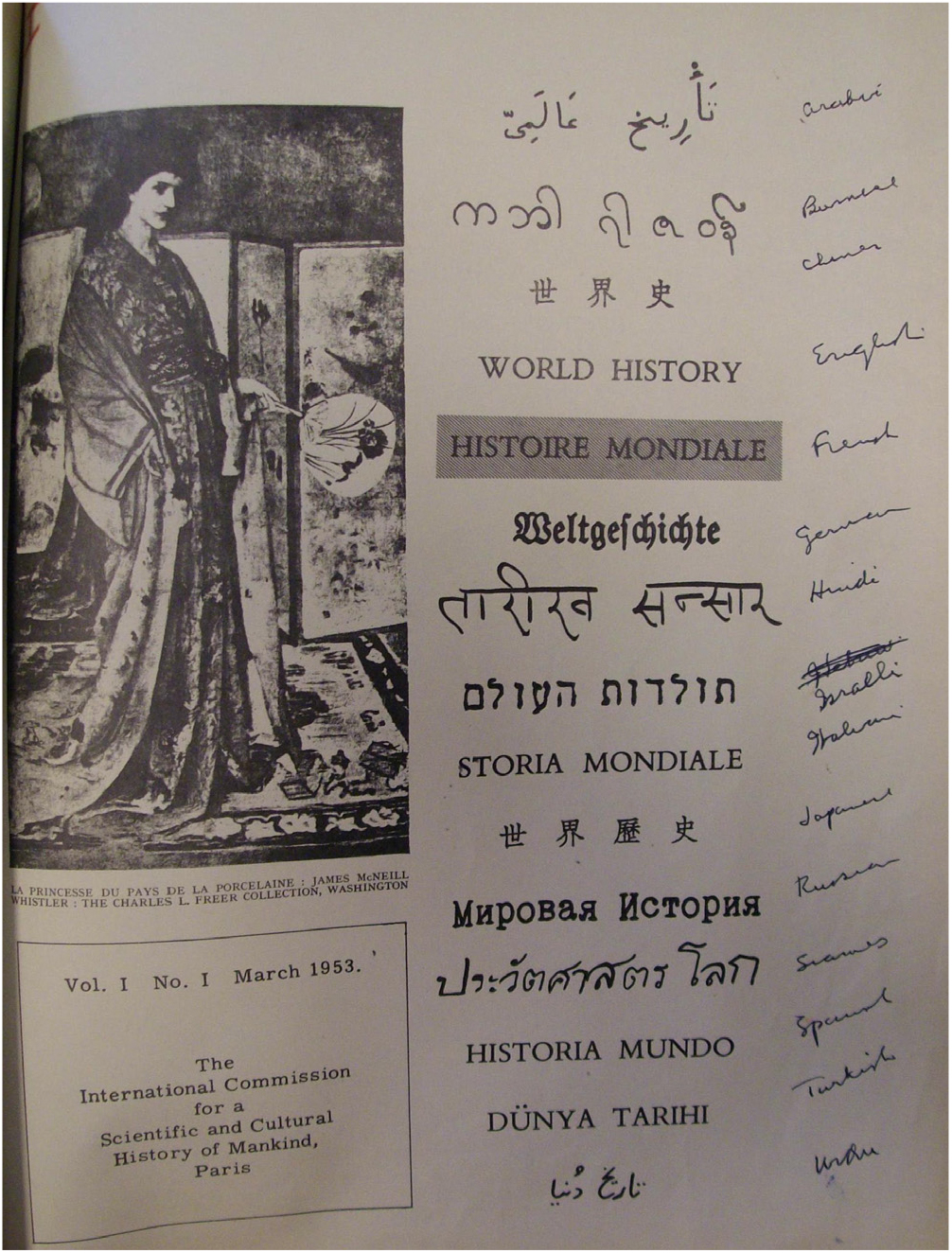

Febvre’s outburst was, in fact, the ultimate manifestation of the tensions that had plagued the whole project from the outset. The first serious bone of contention emerged in 1952, concerning the choice of a title for the new journal. Initially, presumably on Febvre’s suggestion, this had been projected as Historia Mundi. Turner, however, though saluting the choice of Latin as an ‘obvious effort to side-step present cultural nationalisms’, strongly voiced his disapproval: ‘this is the 20th century. Latin is no longer a living scholarly language in the West, and it never was such in the rest of the world. A Latin title will be completely meaningless in Islamic, Hindi, Buddist [sic], and other Asian culture areas.’Footnote 24 The solution he proposed instead was a graphic one: World History in fifteen languages (English included) in alphabetical order, from Arabic to Urdu, with a picture on the side – Whistler’s The princess from the land of porcelain (see Figure 1).Footnote 25 Rejecting Latin universalism as outdated and fundamentally Eurocentric, Turner advocated a new kind of universalism, based on the equivalency of cultures and mediated through translation. This was in spite of the fact that the picture he chose played upon exoticism to advertise the journal (and, through it, the History of mankind) to a larger public of American ‘private scholars’, ‘school teachers’, and ‘lay readers’.Footnote 26 Indeed, the question of language also entailed the issue of the intended audience of the journal, and it is probably because he conceived of its identity as scholarly that Febvre had last-minute qualms, even after the trilingual compromise solution had prevailed, scribbling a design with Orbis Historicus as a ‘proper’ overarching title (see Figure 2).Footnote 27

Figure 1. (Colour online) Cahiers d’Histoire Mondiale, title page project by Ralph Turner, n.d. Source: UNESCO archives, SCHM 50. © UNESCO.

Figure 2. (Colour online) Lucien Febvre, ‘Note pour M. Laurent’, 1953. Source: François Crouzet private papers, Paris.

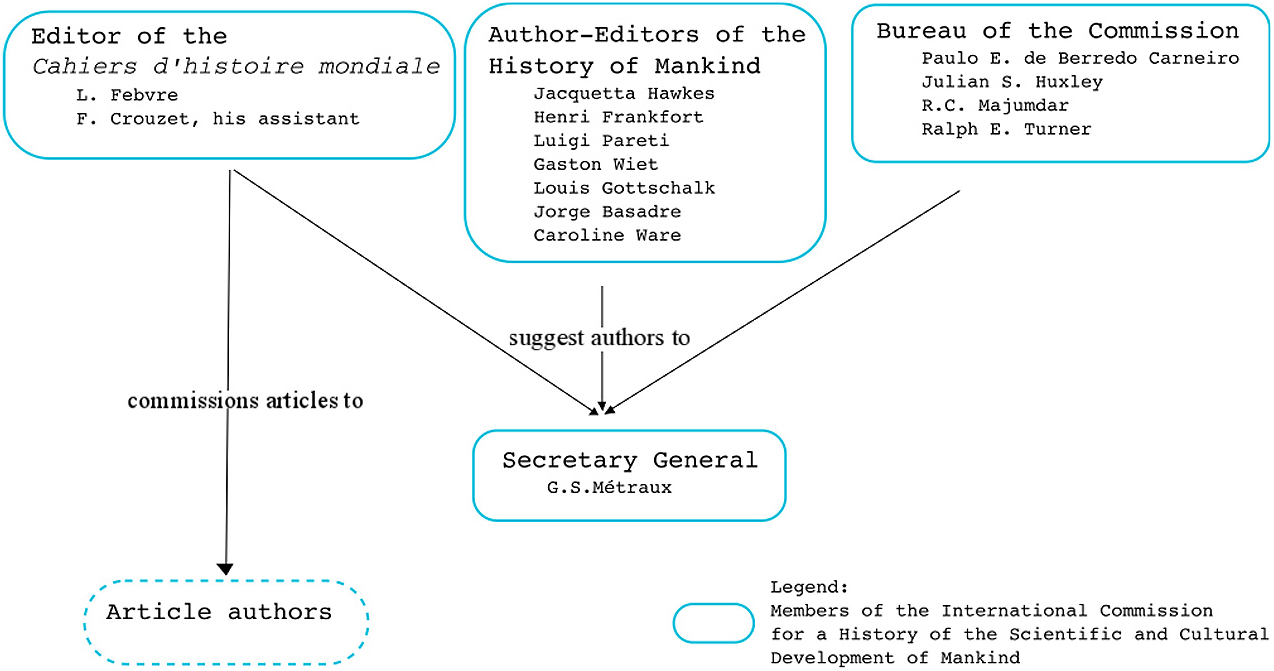

Institutionally, in the initial procedure as established in July 1952, Turner, the chairman of the editorial committee, occupied a central position, assisted by the secretary general, Guy S. Métraux, a Swiss former graduate student from Yale (see Figure 3). In this arrangement, Febvre’s role as editor of the Cahiers was marginal, limited to suggestions, which had to be cleared, like all the others, by Turner. Nevertheless, as early as December of that same year, he took it upon himself to commission fourteen articles from various leading scholars, such as André Piganiol, Pierre Chaunu, Alexandre Koyré, Carlo Cipolla, and Claude Lévi-Strauss, who, in his view, were to ‘resoundingly’ represent the perspectives of the French historical school. The aim of this manoeuvre, which he considered his patriotic duty, was to counterbalance the over-representation of ‘Anglo-Saxon scholars’.Footnote 28 He had profited from being on home soil, whereas Turner, ‘notre Ralph international’ as Febvre dubbed him, had been busy touring the world on a Rockefeller Foundation project.Footnote 29 Yet, by June 1953, Turner, by secretly instructing American authors not to hand in their papers, was jeopardizing the production of the journal.Footnote 30 In December, putting forward the project’s budgetary problems and the need to concentrate solely on the History of mankind, he went as far as to call for the end of the publication of the Cahiers altogether.Footnote 31

Figure 3. (Colour online) Process of commissioning articles in 1952. Source: UNESCO SCHM 1, ‘Procedure for clearing contributions to the Journal of World History’, 22 July 1952.

The publication of the Polish scholar Oscar Halecki’s article ‘The place of Christendom in the history of mankind’ took place at the climax of the power struggle between Turner and Febvre.Footnote 32 The article, which put forward Christendom as a valid unit of analysis in world history, was obviously aimed at countering the very bad image of the UNESCO project in Catholic circles, especially in regard to Turner, who had been dismissed from the University of Pittsburgh in 1934 for his vocal anti-religious views.Footnote 33 Commissioned by Gottschalk, ‘The place of Christendom’ had been backed and validated for publication by Turner, but Febvre did not approve.Footnote 34 There was officially nothing that the latter could do, and, in spite of his best efforts, the article was published in issue number 4. This did not prevent Febvre from trying to insert a footnote where he outlined the ‘normal procedure’ for commissioning articles, (wrongly) attributing their commission to Turner, and making it clear that he did not have any responsibility for its publication (see Figure 4). As with ‘The editor’s role’, this ‘ambiguous footnote’ was not published as such, since Métraux deemed it inadvisable (see Figure 5).Footnote 35

Figure 4. (Colour online) Proofs of Oscar Halecki’s article annotated in the hand of Lucien Febvre. Source: François Crouzet private papers, Paris.

Figure 5. The footnote as it was actually published.

While the Halecki article episode seems to point to Febvre’s marginalization, Turner had by then already lost his grip on the journal. Métraux, backed by Carneiro, had managed to preserve its existence.Footnote 36 The revised statutes from February 1954 (see Figure 6) had enshrined the fact that Febvre was ‘fully responsible’ for the journal, and that he could ‘commission material [that he felt] would make the Journal more readable’.Footnote 37 After a long struggle, Febvre, by carving for himself a true editorship, had finally managed to give to the journal an autonomous existence, both editorial and scientific. He expressed his overall satisfaction in a preface for the first issue of 1956. A few minor problems excepted (moving from the kitchen to the bathroom, he feared the journal might overflow with articles like a ‘bathtub’), the challenge of ‘the first ever attempt at a journal of World History’ had been met.Footnote 38 This, nevertheless, was to be his last contribution to the enterprise, since he died a few months later. From then on, the editorship remained vacant and Crouzet (his title was secrétaire de rédaction) and Métraux stepped in as de facto editors, inaugurating a less conflict-ridden phase in the journal’s history (Métraux would later describe their relationship as ‘cloudless’).Footnote 39

Figure 6. (Colour online) Process of commissioning of articles in 1954. Source: Report by Carneiro and Statutes of the International Commission, CHM, 2, 1, 1954, pp. 225–44.

Soon, with the completion of the History of mankind looming, the pair had to think about reinventing the Cahiers. In 1957, Carneiro consulted the International Committee of Historical Sciences to ask if it would be willing to take charge of the journal. The committee’s president, Federico Chabod, declined, arguing that the Cahiers had accomplished its task. With nothing specific to offer, they would only be one more journal of ‘general history’.Footnote 40 This was not the opinion of François Crouzet, who, in a memo drafted in 1958, defended the Cahiers’ existence by reference to the journal’s ‘true nature’. As he saw it, the Cahiers was the ‘only proper journal of world history’ (‘la seule revue d’histoire vraiment mondiale’), and doubly so: because of the international nature of its authorship (unlike other journals, which had a ‘clear Western orientation’), and because of its contents, dealing as it did with a variety of epochs and world regions in each issue.Footnote 41 In order to keep the journal alive, Crouzet envisioned a ‘new’ formula. It would become a kind of world history forum featuring regular national historiographical updates by historians from different countries. The main innovation would be the special issues around what he called ‘big problems of world history such as the relation between East and West, the Renaissance, the diffusion of Buddhism and Islam, the Industrial Revolution, the contemporary evolution of sciences, arts, culture, etc.’.Footnote 42

This plan won the day, inaugurating a second phase in the history of the journal. In the following years, Métraux devoted a great deal of energy to the ‘new series’. From 1958 to 1970, eleven ‘special issues’ were published. Some of them focused on a geographical region envisioned from a specific point of view (‘Cultural history of India’ (1960), ‘Latin America in the twentieth century’ (1964)), pointing to a different kind of world history, one made from national building blocks and more akin to area studies. Other issues maintained a global perspective, exploring themes pertaining to world culture, such as ‘Encyclopaedias and civilization’ (1966) or ‘Essays on international cooperation’ (1966). Specific marketing strategies were put into place for each special issue. The ‘Science in an American context’ issue (1965), for example, was a ‘personal project’ of Métraux, who drew on his Yale networks to put it together.Footnote 43 He thought of it as a way to expand what seemed to him an underdeveloped field of study, but also as a way of broadening the journal’s audience in the US. Sold at a reduced price and as if it were a book, the issue was ultimately aimed at American undergraduates.Footnote 44 The Cahiers was to soldier on until 1972, when it transitioned into Cultures, with Métraux still at the helm.

The difficult business of world history

The problem of autonomy was also a financial one. Support for Cahiers was included in the global budget of the Commission, which had been initially set at approximately US$70,000 a year.Footnote 45 At the outset, the Commission had contracted with the Paris-based Librairie des Méridiens to publish the journal. After a few months’ collaboration, Métraux complained bitterly about the publisher, noting that ‘his prices are too high, his organization for distribution is non-existent, his vision is narrow’.Footnote 46 The main problem, in fact, was the contract, which stipulated that the Commission was bound to cover any losses that the publisher might incur, which amounted to more or less US$5,000 a year.Footnote 47 By the end of 1954, faced with the prospect of discontinuing the publication, Métraux advocated a change of publisher.Footnote 48 Tapping into his Swiss connections, he proposed a Neuchâtel-based publishing house, La Baconnière. The new arrangement was to reduce the financial burden for the Commission by transferring the cost to the publisher, whose responsibility it was to fend for itself and boost the sales.Footnote 49 The contribution of the Commission was now reduced to paying US$1,500 for 250 subscriptions out of a total print run of 1,000 copies.

Compared to a ‘normal’ scientific journal, the Cahiers, as a UNESCO-financed journal aiming at a global reach, had to face specific constraints and come up with a specific business model. One of the distinguishing features of the Cahiers was that authors were paid for their contributions.Footnote 50 The rate was at first fixed at US$10 per 600 words, before being brought down to US$10 per 1,000 words. Fees to authors represented a sizeable share of the overall budget. For the year 1955, for example, ‘articles for the JWH’ amounted to US$10,154 out of a total budget of US$73,154, much more than the initially budgeted US$2,000.Footnote 51 Another particularity was the cost of linguistic diversity, a crucial part of the project. In the draft budget for 1954, translations had been budgeted on a lavish scale by Charles Morazé.Footnote 52 Abstracts were produced for each article in German, Russian, and Arabic. However, owing in part to the cost, they were scrapped as early as the fourth issue. Even restricted to three languages, the multilingual nature of the journal also entailed delays and costs, because it required different accent marks and frequent mixing of fonts.Footnote 53 It did not simplify matters that the sheer scale of the international collaboration translated into a huge amount of material (each volume was 1,000 pages long).

Achieving a worldwide distribution was the very raison d’être of the journal. ‘If the international collaboration in the History is to be faithfully maintained, the wide distribution of the Journal becomes fundamental’, wrote Métraux to one of the 111 corresponding members who were supposed to spread the word and push for subscriptions in their respective countries.Footnote 54 Nevertheless, as diagnosed by a Canadian scholar, ‘the distribution of UNESCO publications through ordinary commercial book channels, on this continent, is slight – indeed almost non-existent’.Footnote 55 The hope for a worldwide commercial distribution therefore rested on La Baconnière, whose international network of correspondents was one of its assets in Métraux’s eyes.Footnote 56 Many efforts were made over the years to make the journal appealing to a wider readership. Advertising campaigns stressed its international uniqueness, the ‘originality’ of its approach, and the ‘newness’ of its ‘international scientific collaboration formula’.Footnote 57 In 1959, six photographs were printed for the first time and, according to Métraux, the innovation boosted sales during the holiday season.Footnote 58

These efforts were moderately successful at best. Setting aside the UNESCO contingent, which amounted to approximately 250, the number of subscriptions rose progressively, from 332 for the first volume (1954) to a maximum of 726 for the tenth (see Figure 7). Only in 1968 did the total number of subscribers exceed the 1,000 mark, but still the publisher complained that the Cahiers did not earn him any money.Footnote 59 To put this figure into perspective, one might consider that a well-established journal such as the American Historical Review had 10,000 member subscriptions in 1960. While apparently international in scope, with more than fifty countries receiving copies of the journal, diffusion of the Cahiers was not, in fact, evenly spread out. In many countries, the number of subscriptions was minimal, between one and ten, most of them coming from UNESCO members and correspondents. Only in the US (360), France (67), and Germany (43) was the journal somewhat widely commercialized, though even here it was libraries that accounted for the majority of subscribers.Footnote 60 In France, for example, fifty libraries – for the most part university libraries, but also a handful of municipal or museum libraries – hold at least a few of issues of the journal (thirty hold a complete set).Footnote 61

Figure 7. (Colour online) Evolution of the number of subscribers to the Cahiers d’Histoire Mondiale, 1954–1968. Source: UNESCO, SCHM 53, La Baconnière file.

The West and the rest?

‘France, 1; Italy, 1; England, 2; USA, 1; Peru, 1; India, 1: namely, Europe, 4; USA, 2 (Chairman included); South-America, 1; Asia, 1.’Footnote 62 In his aforementioned devastating but censored rant, keeping score of the nationality of the History of mankind author-editors, Lucien Febvre had warned against the overwhelming domination of the West: ‘there can be, and there are, historians both qualified and well known, outside countries of Western culture’. According to him, internationalization was not enough. In fact, he distinguished between two kinds of internationalization. The first was purely bibliographical: ‘the Belgian, Swedish or Portuguese editor of a “World History” launched in Brussels, Stockholm or Coimbra can afford, for a work of national interest, to solicit contributions solely from fellow nationals. Providing they are abreast of the international literature in their field.’ But this would not do in the case of the History of mankind, which was not localized in any sense. In what was probably the strongest echo of the contemporary context of decolonization in the whole dossier, Febvre powerfully upheld the necessity to go beyond Western authorship:

non-European or non-American members [of a world full of defiance] are haunted by the feeling, often justified, that they are being overlooked, even despised, by the bearers of a culture they claim, forcefully and rightfully so, is not the only one entitled (even though its titles are great) to the collective gratefulness of humankind – [authors of an institution such as UNESCO] cannot reinforce so many indefensible prejudices and biases.Footnote 63

Ultimately then, this was a question of numbers. Overall, from 1953 to 1972, 550 authors contributed 625 articles to the journal (62 authors penned two articles or more). An approximation of the authors’ origin is their institutional affiliation, which is systematically recorded in the summaries (see Table 1). Overall, the West’s domination is indeed massive (even though it pales in comparison with masculine domination, since only 23 authors out of the 550 were women), with a little less than two-thirds of authors based in western Europe and North America. The Eastern bloc totals approximately 15%, while the ‘rest’ accounts for the remaining 20%.

Overall, two countries stand out: the US (18.6%) and France (15.3%), together making up one-third of the contributors. Regarding authors based in the US, a rough count by nationality drawing on outside data widely available in directories, obituaries, and library catalogues reveals that, out of the 102 authors in question, only 70 were US nationals at the time of publication – a sign of the attraction of US institutions during and after the Second World War. The prominence of French historians, to the point of hegemony in the first issues, although on the wane in the long run, was obviously the result of Febvre’s involvement.

Table 1. Country of origin of contributors to the Cahiers d’Histoire Mondiale, according to claimed institutional affiliation

Note: Sixty authors put forward two or more affiliations. In their cases, the first is counted as primary, in order to avoid over-representing countries where double affiliation was the norm (Italian historians, for instance, very often claimed the Accademia dei Lincei as their second institution). Of the sixty authors who claimed a double affiliation, the majority (thirty-seven) were attached to two institutions in the same country. The slight drawback of this method is that we ‘lose’ the few cases where an author put forward a transnational double affiliation. Magnus Mörner, for instance, presented himself as ‘Institute of Ibero-American Studies, Stockholm; Visiting Professor of History, University of California, Los Angeles, California’.

Source: Cahiers d’Histoire Mondiale, 1953–1972, summaries.

Other countries in the West that were well represented included Italy (5.8%), the UK (5.0%) and Spain (4.6%). West German historians’ participation, on the other hand, was marginal, with only 2.2%. This was a reflection of the German historiographical landscape during the post-war years, still conservative and national in outlook, as few exiled historians came back, and denazification in the profession was only minimal.Footnote 64 Most spectacularly, Werner Conze, an ex-member of the Nazi Party and deeply involved in the Ostforschung and its scholarly justification of the Third Reich’s expansion towards the East, contributed an article in 1953 on ‘peasant emancipation’ in eastern Europe.Footnote 65

The main non-Western provider of contributors was by far the USSR, which made it to third place with 10.7%. In fact, Soviet scholars started participating only from 1956 onwards, after the USSR had joined UNESCO in 1954, as a consequence of Khrushchev’s Thaw. Many, such as B. M. Kedrov or A. A. Zvorykin, had been marginalized under the Stalinist regime. An ex-professor of the history of technology at the Institute of Mining of Moscow State University, the latter was victim to the purges of the late 1930s, and was expelled from the party, before clawing his way back up the ladder.Footnote 66 One of the editors of the Soviet encyclopedia, he was named vice-president of the International Commission in 1956. With nine articles, he turned out to be by far the most prolific contributor to the journal. Although Febvre, in his last editorial, expressed his satisfaction at the prospect of the Soviets’ participation, he also voiced his concern that the journal might be flooded by Soviet material.Footnote 67 Indeed, in early 1956, Métraux had warned that the Soviets already had around thirty articles ready for publication, and that this might upset the whole equilibrium of the journal.Footnote 68 The solution devised was to collect the articles in a special issue, which was published in 1958, as well as another in 1970.Footnote 69 Although numerous, the contributions of Soviet scholars were in effect confined.

Because mainland China was no longer part of UNESCO after 1949, not a single Chinese scholar contributed. This was despite the fact that Chinese scholars had been very active in the formation of UNESCO, and that Needham had himself drawn inspiration for the whole History of mankind project from his study of the global impact of Chinese inventions.Footnote 70 Two significant providers, on the other hand, were Japan (5.5%) and India (4%). In both cases it appears as though the UNESCO project was infiltrated by a more nationalist brand of historians. Japanese contributors to the Cahiers do not belong to the Marxist historiography dominant during the post-war years. Contributing three articles, for example, was Masaaki Kosaka from Kyoto University, a philosopher belonging to the second generation of the Kyoto school, a group of Japanese thinkers who strove to integrate Western philosophy into the intellectual traditions of East Asia, especially Buddhism. Between 1941 and 1942, Kosaka had participated in a series of round-table discussions (known as the Chūōkōron discussions), which were published one year later under the title The world-historical standpoint and Japan. Although tainted by their association with Japanese militarism during the Second World War, these discussions articulated a vision of a multicultural world order that resonates, in hindsight, with the ideals of UNESCO.Footnote 71 As for Indian historians, they collaborated under the aegis of the Bengali historian R. C. Majumdar, vice-president of the International Commission from its beginning. A specialist of ancient India who had achieved a certain international recognition, Majumdar was in fact a proponent of a ‘communal’ vision of Indian history that emphasized the Hindu element. This is demonstrated by his editorship of the massive History of India then being produced at the instigation of the Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan.Footnote 72 Indeed, Indian contributions to the Cahiers reflect this bent, strongly focusing on ancient India, and belittling the Muslim component.Footnote 73

This general overview therefore presents an image of relative diversity, where the dominance of Western historiography is at least in part counterbalanced by the production of ‘non-European or non-American’ scholars. One should bear in mind, nevertheless, that there was nothing spontaneous about this. Rather, it was the result of a deliberate policy on the part of the editors, as a means to justify their very existence. The turn towards the special issues formula should be considered as such, as a way to boost under-represented historiographies and diversify authorship. The special issue ‘Cultural history of India’ (1960), which featured thirteen articles by eight Indian scholars, had been commissioned ‘at the request of the Bureau’Footnote 74 to showcase the ‘place of India and Indian scholars in our project’.Footnote 75 Revealingly, Crouzet had been quite anxious to have the issue published in time for the Paris General Conference of that year.Footnote 76 In the case of ‘Latin America in the twentieth century’ (1964), Métraux seized on the occasion of a congress held in Bordeaux to publish the papers presented there, most of them by Latin American scholars.Footnote 77 Apart from two early contributions in 1957 by Kofi A. Busia, the future prime minister of Ghana, and Pius Okigbo, the leading Nigerian economist, who was then a lecturer at Northwestern University, both on the issue of the development of West Africa in the face of Western colonization, the inclusion of African scholars (mainly from Tanzania, Ghana, Algeria, and Egypt) was a late development, from the early 1970s, as the UNESCO History of Africa project was taking shape.Footnote 78

After counting authors by origin, Lucien Febvre had, in the same breath, ‘draw[n] the subject matter map’. Although praising efforts to bring in the ‘Far East’, the ‘Ancient Classical East’, and the ‘Islamic world’, he pointed out that there were still many ‘gaping holes’. ‘What? Nothing on immense and secret Africa …. Nothing either on Polar societies …? Nothing on the vast Pacific world …? Nothing either on pre-Columbian civilizations and the many problems they pose? Unforgivable shortcomings.’Footnote 79 The ‘general subject index’ at the end of the last issue gives a first approximation of the overall subject matter. It is organized according to six main headings, of which only the fifth category, ‘Cultural history’, is broken down geographically by areas. The totals are the following: Asia 99, Europe 92, America 55, Middle East 46, Africa 35, Jewish People 22, Oceania 5. This surprisingly polycentric overview, with Europe coming second behind Asia, is nevertheless misleading, as each article only appears once in the index, and as articles in the ‘Economics, knowledge, science’ category are not assigned to a geographical space, thus massively underestimating the weight of Europe. Therefore, this emic count, although interesting in itself, is a distorted reflection of the geography of the journal.

However, coming up with a more accurate count is far from easy, for two reasons. First, a number of articles, whether synthetic or theoretical, are not localized.Footnote 80 Second, articles often deal with several world regions, thus making it problematic to assign them to only one. To try to overcome these two problems, we assigned each article to all the world regions on which its subject matter touches.Footnote 81 Consider Charles Verlinden’s article ‘Les origines coloniales de la civilisation Atlantique: antécédents et types de structure’.Footnote 82 In the general subject index, this article appears under the ‘European history and culture’ heading, thus missing its Atlantic dimension. In our method, the same article appears under four headings: ‘Western Europe’, ‘Africa’, ‘South America’, ‘North America’. When the articles are not localized, we decided not to take them into account.Footnote 83 Figure 8 reveals the density of links between world regions and how they interact with each other.

Figure 8. (Colour online) The world of the Cahiers d’Histoire Mondiale. Each circle represents a world region, its size in proportion to the weighted number of articles dealing with it. The lines represent the weighted number of articles dealing with linked world regions. Articles are weighted by the number of zones they touch upon in order not to over-represent articles dealing with two or more regions, as, without weighting, the more regions the more visual impact an article would have. This explains why Central and Eastern Europe’s circle (88 articles) appears to be similar to Asia’s (138), and why, conversely, Oceania’s is somewhat bigger than its 14 articles would suggest. Two types of links are possible – effective or simply cognitive – in the case of comparative history.

Once again, the West dominates, but not as much and not in the same way. North America appears to be marginal, both in weight and in connections. Thus the ‘West’ here equates mostly with western Europe, which polarizes the world by being significantly connected to all the other world regions, Asia primarily but also the Middle East and South America. Beyond this denser web of connections, the overall picture is relatively diverse. The only dense connections outside Europe are between Asia and the Middle East, and between Africa and South America.

This general overview reveals a somewhat polycentric historiographical world (although strongly polarized by Europe), but one must not lose sight of the asymmetries lurking behind. The first asymmetry concerns thematic subject matter, as is revealed by a systematic tagging of articles (by time period and historiographical field). The distribution of the ‘History of science’ tag, for example, is instructive. Almost one-third of the articles bearing the tag ‘North America’ also bear the tag ‘History of science’. For western Europe, the proportion falls to one-fifth, a little less for Asia (14%).Footnote 84 The remaining parts of the world are much further behind (7% for the Middle East). Conversely, the ‘History of religion’ tag is much more widespread for articles relating to the Middle East (24%) than for western Europe (11%) or North America (9%).

The second type of asymmetry has to do with periodization (see Figure 9). Although the journal, in a general way, leaned strongly towards the modern period, different world regions present different patterns. The Middle East is thus reduced to the ‘Ancient classical East’, that is, a subject of ancient or medieval history, in stark contrast to the ‘Western’ pattern, where early modern and modern history dominate.

Figure 9. (Colour online) Articles appearing in Cahiers, by period and world region.

The third, and most glaring, type of asymmetry has to do with perspective. Who wrote about whom? The overall weight of Asia, for example, is mainly due to that of Indian and Japanese history, with respectively thirty-five and thirty-three articles, a direct consequence of the number of contributors from these two countries. On the other hand, China is the subject of only sixteen articles, all written by Western and Japanese orientalists. This ‘passive’ tendency is also obvious in the case of the Middle East, until the 1970s. The corollary is that authors from France and the United States did not limit themselves to their national histories, casting a wide net all over the world.

One of the most original features of the journal was its multilingual ambition, conceived as a means of diversifying the readership as well as the authorship. Yet the universal reach conjured up by Turner’s cover project never even remotely materialized. In the end, the journal was de facto bilingual, with 58.4% of articles in English and 37.8% in French. At first, the balance had been in favour of French, to the extent that Carneiro had to intervene to ask Febvre to include more articles in English.Footnote 85 This was due to the fact that, in the 1950s, French was still the language of international expression for scholars from Latin-language-speaking countries as well as from large parts of the Middle East and Africa. It was only from 1960 onwards that English became really dominant. From then on, the share of articles in French was somewhat artificially sustained by the translation of articles from other languages.Footnote 86 Spanish, the third official language, represented a paltry total of 3.8%. After only two articles in Spanish had been published in the first volume, out of a total of forty-six (compared to twenty-five in French and nineteen in English), Febvre was compelled to explain that this meagre showing was because of a dearth of submissions, ‘those for whom Spanish is the language of use preferring to write in English or French’.Footnote 87 As stated above, abstracts in German, Russian, and, beyond a purely Eurocentric perspective, Arabic, were systematically provided until the fourth issue. They were then scrapped, not only because of their cost, but also because of their poor quality. The first abstracts in Arabic were judged by the chief of the UNESCO translation section to be the work of ‘a North-African, or a Jesuit father, or an orientalist; certainly not a modern writer. The style has a “priestly” quality that makes it difficult to understand. It seems as though the translator has no contacts with exterior life whatsoever since he employs the language of a chronicler.’Footnote 88

World history as a forum for debate

The goal of the journal, as officially defined from the outset, was not only to provide material for the History of mankind. Its mission was also to ‘sift this material through the strict criticism of well-known and qualified scholars and specialists’ and to ‘enable erudite persons from all countries to participate in a debate’ on world history problems.Footnote 89 This role devoted to ‘debate’ on two levels (that of professional scholars and that of independent scholars) is a testament to Turner’s influence in the early stages. Significantly, in the first issue of the second volume, the ‘Suggestions’ section, aimed at fostering commentary on previous articles, was introduced as Turner’s very own preserve.Footnote 90 Indeed, Turner thought of ‘ideological differences’ as the engine of world history, ‘as an aspect of the integration of supra-national groups’ into a world community.Footnote 91 They were thus to be ‘studied not merely as obstacles to the development of world organisation but also as potential bases for such organisations’.Footnote 92 The writing of world history was to mirror this process and the journal was to serve as the vessel for the expression of conflicting views. Turner, for example, advocated the publishing of an article by Ashley Montagu on the ‘bio-social nature of man’, which had garnered widespread criticism inside the editorial committee, not so much because of its content (Montagu had drafted UNESCO’s anti-racist 1950 ‘Statement on race’), but because of its polemical and ‘vituperative’ tone against the ‘constitutionalist’ theories of the psychologist W. H. Sheldon.Footnote 93 ‘I think’, Turner wrote to Métraux, ‘it would be a great mistake if we should adopt a policy of publishing only these articles which we regard as non controversial.’Footnote 94 Thus, world history as he saw it was constructed out of a multiplicity of viewpoints. ‘By this device, the history will be, at once, both a coherent discussion of the human career and a record of different points of view towards an interpretation of either parts or all of it.’Footnote 95 This intellectual stance was also a commercial one. Indeed, for Turner, ‘scholarship [was] not enough’.Footnote 96 He was convinced that this controversial dimension could contribute to the ‘attractiveness’ of the journal as a product aimed at a wider public. This idea was taken up again a few years later by Métraux, who wanted to solicit readers and ask them for commentaries in view of what he considered the ‘open forum nature of the Cahiers’.Footnote 97 But Febvre balked at the suggestion, fearing that it would mean opening the door to ‘the nationalist and racist fancies of unread and unsympathetic ordinary people’.Footnote 98

The question was not only who could participate in the debate, but the nature of the articles capable of fostering it. This issue had been raised by Charles Morazé after the publication of the first issue. Morazé was disappointed that the articles had provoked very little reaction or criticism. This, according to him, was less due to their intrinsic qualities than to the fact that they were ill suited to the goal of the Cahiers, which was to ‘raise a widespread surge of interest in world history problems’. The challenge was that of generality – of striking a balance between specialized erudition and overly broad overviews. ‘The Cahiers should publish only already large syntheses – large but not too large nevertheless. Fifteen page universal histories will not amend for long erudite articles on small problems. What are the volume directors to make of them? How can our readers provide precise and to the point criticisms?’Footnote 99 For Morazé, rather than by the diversity of the authors’ origins or of subject matter, the UNESCO world history would be made truly global by the scrutiny to which its contents would be publicly subjected on a worldwide scale.

In practice, a section of the journal was specifically devoted to critical comments upon already published articles, usually followed by answers from their authors. Although a range of articles were discussed, the section was largely polarized by debates around Marxism, where Soviet scholars figured prominently. This was due to the fact that they had their own world history project under way, the massive Vsemirnaiia istoriia, edited by the Japanologist Y. M. Zhukov. Their contribution to the Cahiers therefore had a twofold purpose. The first was to promote their ‘World history’ and give it international recognition.Footnote 100 The second was to weigh in on the UNESCO project and try to influence it by defending their own vision of history. In recent years, Soviet participation in the writing of the History of mankind has received its fair share of scholarly attention.Footnote 101 The overall impression drawn from these studies is at best one of systematic obstructionism, at worst a kind of footnote Cold War of attrition between irreconcilable ideologies. However, focusing on the Cahiers somewhat modifies this perspective, as they were promoted as a kind of forum for historiographical dialogue between East and West.Footnote 102

The most interesting sequence of articles, on the principles governing the writing of global history, was generated by Marshall Hodgson’s foundational article ‘Hemispheric interregional history as an approach to world history’.Footnote 103 In this piece, Hodgson advocated the necessity for the world historian to maintain a ‘world orientation’ when studying his objects. World history for him was a problem of perspective. Most decisively, he condemned Eurocentrism, what he called the ‘westward distortion’, deconstructing categories such as the ‘Orient’ or ‘Asia’, to promote instead an integrated study of the ‘Eastern Hemisphere’. Two years later, Zhukov reacted to this proposal. On the whole, he enthusiastically endorsed the ideas of his American colleague, especially his critique of Eurocentrism.Footnote 104 This was not mere rhetoric, as demonstrated by the fact that he had Hodgson’s article translated in Vestnik istorii mirovoi kul’tury (Herald of the history of world culture), the Soviet equivalent of the Cahiers.Footnote 105 However, this did not prevent Zhukov from taking issue with Hodgson’s analysis of Marxism. According to the latter, indeed, even ‘so great a historical analysis as the Marxist’ had been contaminated by the ‘pervasive effect of westward distortion’ and needed to ‘patch up’ its stadial theory, to take into account the global dimension of history.Footnote 106 For Hodgson, there was no ‘universal scheme into which all history will fit’.Footnote 107 This annoyed Zhukov, who considered Hodgson’s vision to be ‘nihilist’, and argued for the primacy of socioeconomic conditions as the organizing principle of world history.Footnote 108 Two years later, the Italian scholar Silvio Accame rekindled the debate. Although apparently endorsing the critique of Eurocentrism, he made the case for a ‘personalist’ history of the world driven by human rights, which adopts a Judaeo-Christian point of view.Footnote 109

Another interesting set of articles comprises the papers by Busia and Okigbo on West African history, together with their responses to comments by the Soviet scholar N. Gavrilov. Busia and Okigbo had used the impact of British and French colonialism on the history of twentieth-century West Africa as their framework, but Gavrilov criticized them for both overstressing this outside influence, as opposed to the endogenous dynamics of local society and capitalism, and presenting an unduly optimistic picture. Faced with this Marxist critique, it is revealing that both African historians advocated a nuanced position, stressing that colonialism had not been ‘in no way beneficial’.Footnote 110

An experiment in global history?

We have seen the efforts that went into widening the geographical and cultural scope of the journal and the somewhat mitigated success they met with. Beyond this worldwide juxtaposition of local histories, articles using the world as a framework for analysis and an object of inquiry were few. The titles of just 15 articles out of the 625 (2.4%) contain the word ‘world’ in one form or another, excluding localized or temporalized variations such as ‘monde arabe’ or ‘modern world’. This can seem meagre, and one could be forgiven for thinking that there is nothing much of interest here for today’s global historian.

However, a closer look reveals that a considerable number of articles, namely 146 (23% of the total), without covering the whole span of the globe, can be said to experiment with some form of what we might call ‘relational’ history, meaning that their frameworks transcend the clear-cut boundaries of monographical articles. These relational articles are either those whose title explicitly mentions two or more geographical entities, such as a city, country, or continent (including articles on comparative history), or, because titles are not always explicit, articles that clearly link phenomena beyond historiographical boundaries.Footnote 111 Some of these, whether transnational, comparative, trans-imperial, or connected, strongly echo many of today’s preoccupations in the field of global history, largely defined.Footnote 112 Others are not always free from the weight of the national, powerfully embedded in the institutional workings of UNESCO. Tellingly, one of the main keywords of this relational history is ‘contribution’. The articles bearing this term in the title all follow the same national and reifying logic, arguing how one country ‘contributed’ to the more general process of the history of humankind or how one cultural trend contributed to the make-up of one country.Footnote 113 Among other notable keywords, one may distinguish between one-way street concepts (‘impact’, ‘influence’, ‘diffusion’, or ‘spread’) and two-way street concepts (‘relations’, ‘interaction’, ‘influence réciproque’, or ‘osmose’).Footnote 114

The use of the latter set is striking. Their main purpose was to challenge a vision of Westernization operating in a vacuum to stress instead the agency of the ‘rest’. This idea is well encapsulated in the British anthropologist D. F. Pocock’s article on the ‘interaction’ between India and Britain in the nineteenth century and how Britain was in turn affected.Footnote 115 We may remark on the striking similarities between the argument of Masaaki Kosaka in an article on the ‘aggressive influence’ of the West on Tokugawa Japan and K. Little’s article on the ‘Western intrusion’ in African culture. Although both titles cast the West in a negative light as a destructive force impinging on non-Western societies, the conclusion of both essays is in fact more nuanced, in that they put forward a kind of socio-cultural co-production.Footnote 116 In the end, nevertheless, articles such as these are also a testimony to the sway held by the ‘West versus the rest’ dichotomy.

Conclusion

As shown by a recent exchange in the Journal of Global History, the genealogy of global history as a field is still far from clear.Footnote 117 When we started working on the Cahiers d’Histoire Mondiale it was surprising to what extent the journal was unknown, even to serious practitioners of global history.Footnote 118 Hopefully, this article will have contributed to recovering the forgotten world history moment of the 1950s, before area studies swept the scene. The question, nevertheless, remains: why did the Cahiers fall into oblivion? The rich archival material at our disposal afforded a rare opportunity to delve into the ‘kitchen’ of world history, and to understand it as practice. From this vantage point, it appears clearly that the Cahiers, compared to the typical scholarly journal, had to grapple with a fundamental heteronomy. A UNESCO-sponsored journal, it was first and foremost committed to the preparation of the History of mankind, and not to the furthering of a research agenda. Yet the editors did manage over the years to carve for it a share of autonomy. According to Latour, the proponent of a scientific fact or paradigm can hope to establish it only if he or she manages to enrol ‘others’: they are the ones who hold the key to its diffusion and durability.Footnote 119 This is probably then where the Cahiers failed: in enrolling historians and readers. Although 550 historians contributed articles, they did not become proponents of the world history paradigm. Even Febvre, its editor, did not promote the journal in France.Footnote 120 As for Japanese and Indian historians, they widened the geographic scope of the journal, but, through the highlighting of their countries’ contributions to world history, they were in fact promoting a nationalist agenda at home. Readers were also thin on the ground, in spite of the editors’ repeated efforts at commercial distribution.

Although its reach was restricted, the journal was significant nonetheless. The Cahiers was at once a laboratory which experimented with new forms of relational history, and a forum where the very nature of global history was discussed by scholars from around the world (mainly from the West, but also from the East and the South). As such, it is surely relevant to today’s historiographical debates. According to Richard Drayton and David Motadel, ‘the edited volume and the work of translation are the natural media of global history’.Footnote 121 The creators and editors of the Cahiers put their faith in the format of the scholarly journal. They believed in its potential for showcasing diversity (whether in authorship, subject matter, or language) and creating debate. Is this not still the case today?

Gabriela Goldin Marcovich is a doctoral candidate at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris. Her research centres on the Mexican Enlightenment and explores the relationship between urban social networks and intellectual production in the eighteenth century.

Rahul Markovits is associate professor (maître de conferences) in early modern history at the École normale supérieure in Paris. His research focuses on the circulation of people, texts, and culture on a transnational scale during the long eighteenth century. His first book, Civiliser l’Europe: politiques du théâtre français au XVIIIe siècle (2014) is due to be published in English by University of Virginia Press.