Ashvaghosha, an eminent Buddhist sage and scholar of the Kushan era (first to third centuries CE), is considered one of the first Indian playwrights. Prior to becoming a playwright, he had left his birthplace in central India and taken up residence in the north-western part of India, in a region then known as Gandhara that, in present-day terms, extends from northern Pakistan to eastern Afghanistan. He wrote in Sanskrit rather than in one of India’s vernacular languages, and his dramatic themes were explicitly Buddhist. At the time of his arrival in Gandhara, the rulers of this region were no longer home-grown Indian. In fact, Gandhara had become a core area of the Kushan empire, which was founded and ruled by Central Asians. Thus it was that this highly cosmopolitan empire became a major centre for the development of Indian drama. During the time of Ashvaghosha, when Indian drama was packed with Buddhist themes, in the same Gandharan region a new style of Buddhist sculptural art emerged. Both the new drama and the new style of sculptural art soon became powerful methods for propagating Buddhist ideas all the way from India to Central Asia and China. One may ask what was it about Gandhara that inspired Buddhists living within the Kushan kingdom to create both a new style of sculptural art and the altogether new dramatic performances to express their devotion. Although the Hellenistic characteristics of Gandharan Buddhist art have long been recognized as such, Hellenistic influence on Sanskrit drama is not so apparent. Thus this study will trace the spread of Greek drama, along with other Dionysian traditions, to Gandhara and explore the impact that it had on Buddhist art and drama, as well as the nature of the relationship between these two forms of Buddhist cultural expression.

The coming of Dionysus to India

In the latter part of the fourth century BCE, when Alexander of Macedonia began his departure from his easternmost conquests and boated down the Indus River toward the Arabian Sea, he left behind him, throughout all the Hellenistic kingdoms, numerous Greek garrison cities named Alexandria, many of which continued to flourish as economic and cultural centres long after his demise. On the eastern edge of the Hellenistic conquests, Bactria (in present-day Afghanistan) became the only kingdom to successfully declare its independence from the Seleucid empire, which took over control of Alexander’s conquests in Iran and Afghanistan after his death. Although rejecting Seleucid political control, Bactria nevertheless developed into a powerful base for the establishment and spread of Hellenistic culture, extending its territory and its influence all the way to north-western India. As did many of the Hellenistic cities of that time, those in the east maintained most of the notable features of a Greek polis. One could usually find a Greek-style palace, which functioned both as the residence of the king and as the centre for administration; a gymnasium that provided both physical and intellectual education; an agora, which was both a marketplace and a place of social gathering; and temples for the patron deity of the city and for other deities from Greece, Iran, and India, which were lined up along a colonnade of Corinthian columns. Last, but not least, perhaps the most significant marker of these cities was the theatre, which was usually associated with a temple dedicated to the Greek god Dionysus.

In Afghanistan, near the village of Ai Khanoum, archaeologists discovered the ruins of a Hellenistic city dating back to the time of Hellenistic Bactria. The name of this Greek city during its prime is still a matter of speculation. The archaeological site, which lies on the southern bank of the Amu Darya (known to the Greeks as the Oxus and at present marking the boundary between Afghanistan and Tajikistan), has all the traits of a Greek polis. Here, French archaeologists found a theatre with a stage and several rows of seats, among many other ruined edifices. According to Paul Bernard, the excavator of the site, in the theatre ‘35 tiers fan out over a semicircular area with a radius of 42 meters’, indicating that such a structure could have accommodated an audience of 6,000 people.Footnote 1 Also, among the architectural remains is a stone piece, from a water fountain, that closely resembles a mask used in Greek comedy (the water flowed out of the mask’s mouth). The finding of this image (Figure 1) suggests that the civic theatre was indeed used to stage dramas, probably comedies.

Figure 1. Mouth of a water fountain in the shape of a comic mask, Ai Khanoum. Paul Bernard, DAFA.

During the second century BCE, nomadic tribes, including the Parthians, Sakas, and Yuezhi in succession, overran Bactria, and one or more of them overthrew the Greek regimes there. The details of these events are not certain.Footnote 2 The Greek city at Ai Khanoum most probably ceased to be Greek around 145 BCE, the year that Eucratides, its last Greek king, issued the kingdom’s last coin.Footnote 3 The coming of the nomads did not, however, seriously disturb the well-rooted Hellenistic culture there. It seems that the nomads soon became accustomed to ruling a sedentary society and enjoyed its urban culture. Hellenistic architectural features (including Corinthian columns) survived in the region, under now-sedentarized nomadic rulers for many centuries.

The nomads not only settled in Bactria but also proceeded from there to India. The Guishuang tribe, one of the five tribes of the Yuezhi confederation, eventually reunified the confederation, giving its name to the Kushan kingdom that subsequently emerged. Around the middle of the first century CE, the Kushans crossed the mountains known as the Hindu Kush and entered India. By this time, their rulers had been settled in Bactria for more than 150 years, had become familiar with its multicultural environment, and had become competent managers of agricultural lands. In addition, by that time they ruled an empire that stretched across Central Asia from China’s frontier to the borders of north-western India. After entering India, they established a new capital at Mathura – a city on the Yamuna, a tributary of the Ganges River – which gave them easy access to the north Indian plain.

By this time, the Kushans were exceedingly cosmopolitan. In Kapisa (modern Begram), on the cool highlands of what is now Afghanistan, archaeologists have discovered a treasury full of exotic goods, brought there from all directions by traders and envoys. The abundant treasures suggest that this was a royal storage house of the Kushan rulers. Among the Western items from this Kushan palace is a bronze theatre mask of the Greek god Dionysus, or one of his followers, the head covered by grape-laden vines: in Greek mythology, Dionysus was closely associated with the origins of both theatre and wine. Unfortunately, damage to the archaeological site at Begram is extensive, and the few surviving architectural remains do not include any trace of a theatre.Footnote 4 Nevertheless, that this theatre mask was still considered to be a treasure several hundred years after the defeat of the region’s Hellenistic political powers suggests a continuing regard for Dionysian festivities and drama in this locale.

The Kushan empire commanded a strategic position in Eurasian trade and benefited greatly from flourishing commerce on the Silk Road between China and the Arabian Sea. The treasures in the Kushans’ summer palace demonstrate their far-flung commercial ties. Among the items from the Mediterranean is a large crystal vase with a carving on its side of Poseidon, the Greek god of the sea, standing on a tower.Footnote 5 The tower obviously represents the lighthouse that stood at the mouth of the Nile River, overlooking the port of Alexandria, a building that was well known in the ancient world. During the first centuries CE, when the Kushan kings or merchants working under their protection were collecting such beautiful things from all directions, Roman traders, mostly Greek-speaking Egyptians, reached the coast of India by way of the Red Sea and the Arabian Sea. The goods they took home, including Chinese silks, were portaged from the Red Sea to the Nile, and then taken northward, going downstream on the river to the Mediterranean port of Alexandria, where the Roman empire collected tariffs from traders coming back from the east. The vase described above, and some of the glassware in the Kushan treasury at Kapisa, came from Alexandria. Thus, within the lands that became the territory of the Kushan empire, the Hellenistic cultural presence first established by the expedition of Alexander was reinforced, beginning in the first century CE, by overseas commercial ties between the Mediterranean and Gandhara.

Like citizens of Hellenistic cities around the Mediterranean, residents in cities of the most eastern domains of the Hellenistic world maintained the whole package of Greek cultural life. They participated in the physical exercises and intellectual studies available at the city’s gymnasium, worshipped various deities in their temples, and gathered at the theatre to celebrate Dionysian festivals and to watch plays. Except where the climate discouraged it, viticulture – the agricultural process of raising grapes and producing grape wine – was one of the most important economic activities in all the Hellenistic areas. Viniculture – the rituals, etiquette, containers, vessels, and other objects associated with wine drinking – was always present in their cities. Even in those areas where grape vines did not flourish, cities with Hellenistic traditions managed to obtain wine for their Dionysian festivals. Indeed, in Central Asia, it had been the successors of Alexander who had promoted both viticulture and viniculture. After Alexander’s death, when the Seleucids and the Bactrian Greek regimes gained control of Sogdiana, Ferghana (both of which are in modern Uzbekistan), and Gandhara, viticulture and viniculture developed into well-established enterprises, accompanied by a distinctly Hellenistic culture. When the archaeologist Paul Bernard located a Greek garrison at the site of Afrasiab near Samarkand – a major city in ancient Sogdiana, now in southern Uzbekistan – he discovered that the soldiers there had drunk their wine from Greek-style vessels. He also found a krater, a flat-bottomed jar used to serve wine, that, curiously, had two ear-shaped handles like those on amphorae.Footnote 6 The krater also had an interesting non-Greek feature: a human bust carved on the jar’s side is not a Greek deity but apparently a Persian prince.Footnote 7 It should come as no surprise that such a non-Greek feature decorated a Hellenistic vessel found at a location so far east of Greece. Alexander left behind at secured garrison sites soldiers who were not necessarily of Greek origin. Many of them were recruited after his expedition had already reached locations far from his homeland. After he departed from a garrisoned site to carry on his conquests elsewhere, the soldiers who were left behind to hold the region soon realized that they would never be able to return to their homes, and so they married local women and became participants in the local culture. Thus, in those areas where elements of the Dionysian festivities survived, many of the decorative designs on the various vessels associated with wine-drinking displayed non-Greek features.

Even after Greek political power faded from Sogdiana and the Ferghana valley, viticulture remained a major agricultural endeavour in those regions. When the Chinese envoy Zhang Qian visited the Ferghana valley during the latter part of the second century BCE, he called the region Dawan, the name of one of the Central Asian peoples. He noted that viticulture was flourishing, though he did not mention Greek power in that region. According to Zhang Qian, wealthy people there owned tens of thousands of jars of wine, were skilled in the technology of preserving it, and were thus able to keep it for decades.Footnote 8

One cannot assume, however, that a region where viticulture had developed was necessarily Hellenized. Only if the region also yields evidence of the ritual drinking vessels associated with Greek viniculture, as well as evidence of a Dionysian tradition, is it clearly a place where Hellenistic traditions were relevant. For example, in Ferghana there was viticulture but no Hellenistic viniculture consisting of a distinctive ritual apparatus developed in association with wine-drinking. On the other hand, in Sogdiana, south of Ferghana, Hellenistic viticulture and viniculture were both practised. In the latter part of the second century BCE, the Hellenistic powers established during the time of Alexander had recently been defeated by expanding and migrating Central Asian steppe powers, and it would not be until the end of the second century BCE that one of these powers, the Yuezhi-Kushan, would begin to incorporate into their own culture the Hellenistic elements of what had recently been the Greek kingdom of Bactria, including, among other things, its long-standing viticulture and viniculture.

However, after the Kushans had crossed the Hindu Kush in the first century CE and established control over not only Gandhara but also other Indian lands as far south as Mathura, they often found themselves in places where the climate suited neither viticulture nor the preservation of the quality of imported wine. Nevertheless, many of these places were not without Greek wine prior to the Kushan expansion into India. The residents of some of these more southern cities had become enthusiastic consumers of grape wine and had maintained a Greek-style viniculture ever since the time of Alexander. In Sirkap, a residential area of Taxila, now in Pakistan, the archaeologist John Marshall found that many of the flat-bottomed kraters with the amphorae-like ear-shaped handles were in use long before the arrival of the Yuezhi nomads in Bactria.Footnote 9 In addition, he found locally manufactured small amphorae. This makes it clear that at least some Gandharans, were they descendants of fourth century BCE Greeks or Hellenized local peoples or both, apparently maintained their taste for and their supply of grape wine and ritual vessels associated with it for many centuries after the death of Alexander.

After the departure of Alexander down the Indus River, Gandhara was under Indian rule, at least part of the time. In the fourth century BCE, the Mauryan empire had risen on the lower Ganges plain and expanded from there, becoming neighbour with the Seleucid empire. After a battle between the two powers, the Mauryan empire successfully established its hegemony over both Gandhara and Kandahar, another Alexandria, located in southern Afghanistan. In a diplomatic agreement that followed the war, the Indian empire agreed that the Hellenized cities could maintain their local autonomy and continue to use the Greek language, even for official business.Footnote 10 When Ashoka, a Mauryan king who ruled during the third century BCE, had his edicts carved on rocks and pillars all over India, those carved in the Hellenized regions of the north-west were in both Greek and Aramaic, the official language of the Parthian empire in Iran. In addition to speaking Greek, residents of these cities tried to maintain a Greek lifestyle. Unfortunately, because of the limited number of archaeological excavations in these areas and the great damage to the sites, they have not contributed much to our knowledge of Hellenistic life. None, for example, are as well preserved as the site at Ai Khanoum, where, before recent destruction and looting, the remains of an entire city were still available for study.

One of the strongest pieces of evidence for the persistence of Greek culture in what was India is the presence of elegant drinking vessels. India had long had a tradition of making alcoholic beverages from food grains, but the people using those elegant goblets and serving cups probably preferred grape wine. According to the Arthashastra, a thesis on political theory written by Kautalya for the Mauryan rulers, a special kind of wine known as madhu was imported from a region that he called ‘Kapisayana’, which was north of the Hindu Kush.Footnote 11 Kautalya did not provide the exact location of Kapisayana, but the name clearly indicates that it was in or near Kapisa (modern Begram), in the highlands of Afghanistan. Madhu was both sweet and imported, and thus, among the elites who could afford it, it was more in demand than local Indian alcohol. As previously mentioned, Kapisa was also the locale where the Kushans eventually built their summer palace some two hundred years after the demise of both the Greek kingdom in Bactria and Mauryan power in India.

As John Marshall put it, it was only ‘by the time of the Parthians’ that large imported amphorae appeared in Gandhara.Footnote 12 In other words, it was only after Central Asian nomads – Parthians, Sakas, or Kushans – had occupied parts of Gandhara that large, Greek-style, imported wine vessels came into use. They are numerous in archaeological sites, as are many smaller drinking vessels, such as tall, footed goblets made of silver, glass, and ceramics.

Once the wine was transported across the Hindu Kush to the south, preserving its quality would have been a major challenge, thus making viniculture more difficult in these locations than in Bactria and Sogdiana. One problem was the difficulty of growing grapes in places where heat, humidity, or monsoon rains would limit harvests. A second problem was that even imported wine would soon degenerate into vinegar without refrigeration in the hot climate. To prevent wine from degenerating, one needs to add sulphur to stop further fermenting, as modern wine-makers do. Another alternative is to distil the wine, a process that condenses it and, at the same time, increases the concentration of ethanol (the alcoholic content) to the point that it deactivates the yeast. This technique is also common in modern wine-making countries.

The archaeological record clearly indicates that the distillation process was used to preserve wine in some of the Hellenized cities of Gandhara. Although it is generally accepted that distillation was invented by the Arabs to condense perfumes some time around the eleventh century CE, scholars of ancient India do not seem to have even asked the question of how Indians from the Kushan period preserved their wine. In 1951, when Marshall discovered several unusually shaped ceramic jars at Taxila and reconstructed these vessels as part of a distillation apparatus, few people paid attention.Footnote 13 The big, round-bellied jars, stained with soot and burn marks, seem to have served as the first container of the unprocessed wine. A fire lit under the container heated the wine until it evaporated and flowed through a tube into another jar, which collected the vapour. The receiving jar, seated in cold water, condensed the vapour, turning it back into wine.

Marshall’s strong evidence for distillation in India had been in his book and in museums for decades without attracting much attention from scholars until another archaeologist, F. R. Allchin, discovered many more such utensils at Shaikhan Dheri, the site of the Kushan city Pushkalavati, near modern Peshawar, in Pakistan.Footnote 14 At the site of a Buddhist shrine, Allchin found a few soot-stained jars, water basins to cool the vapour, and numerous condensers that received and stored the distilled wine. Although the jars and basins would have made a modest number of distillation sets, there were more than one hundred condensers lined up in a 350-square-metre space.Footnote 15 All these condensers, from both Shaikhan Dheri and Taxila, have a standard size of about 7.5 litres, which, Allchin speculates, was intended to be one-fifth of the capacity of an Attic amphora of 39 litres, a typical vessel for transporting Greek-exported wine.Footnote 16 Two more receivers for distillation, similar to those from Shaikhan Deri, have also been found at the archaeological site of Bir-kot-ghwandai in the Swat valley of northern Pakistan. They have been dated by Pierfrancesco Callieri to the first or second century CE, and one of the two examples has a Kushan tamgha on it.Footnote 17 The archaeological evidence is corroborated by a passage of the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya, a Buddhist monastic code, possibly redacted in Gandhara during the Kushan period, which discusses grapes, wine, and distillation. When the Buddha was travelling in the north-west along with a retinue of monks, a yaksha offered them grapes. The monks did not know such fruits, and thus the Buddha explained them: ‘These are fruits from the northern region. They are called grapes. One can eat them after having purified them with fire.’ Apparently, after the Buddha and his monks ate some of the grapes, and there were some left, he added: ‘The grapes should be pressed to extract the juice, and then the fluid should be heated and removed from the fire before it is completely cooked … To store the syrup and serve it to the samgha out of the proper time, one should heat the juice until it is completely cooked’.Footnote 18

It is now clear that this kind of distilled wine was produced and consumed in the region of Gandhara from the second century BCE to the fourth century CE.Footnote 19 Also at the Buddhist shrine of Shaikhan Dheri, Allchin discovered that local Kushan authorities licensed the distillers and stamped the Kushan royal tamgha on one side of the condensers.Footnote 20 The wine was then sold in the same container that had collected the vapour and condensed it, once it had been filled and sealed with a stopper.Footnote 21 It thus appears that the wine-distilling business was supervised and taxed by the Kushan government, and therefore the princes from the Central Asian steppe were engaged in the business of Dionysus.

Dionysus in Buddhist art at Gandhara

At the beginning of the Common Era, when the Kushan kings took control of Gandhara and Buddhism emerged there as a major force, viniculture and Dionysian traditions were still present in the region, as shown by images linked to the cult of the god Dionysus that were frequently incorporated into Buddhist sculpture. The impulse for the creation of Buddhist visual narratives in the region probably came from the world of theatre and thus may be linked to the Dionysian tradition. In particular, the radically new way in which Gandharan art presented the Buddha’s life, as a sequence of prototypical events, may have been inspired by representational modes used in dramatic performances.

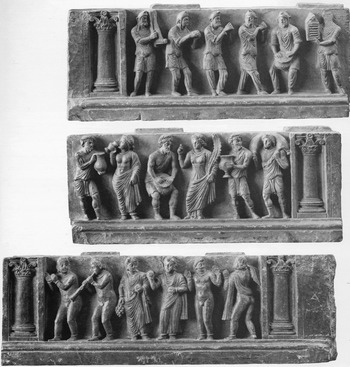

Dionysus, a multifaceted god associated with nature, fertility, wine, music, and theatre, was one of the oldest and most revered deities of the ancient Greek world. Rituals celebrating Dionysus often involved transgressing the boundaries of commonly accepted behaviours. Intoxication, music-making, and dance were practised by his divine and human followers alike. Gandharan images making clear reference to the Western god Dionysus and his rituals are recurrent in the Buddhist sculpture of the pre-Kushan and Kushan period; and that sculpture displays a unique blend of South Asian and Western forms. Some Gandharan examples are a toilet tray (Figure 2),Footnote 22 a Dionysian terracotta head (Figure 3),Footnote 23 and reliefs depicting drinking and dancing (Figure 4).Footnote 24

Figure 2. Toilet Tray from Gandhara. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, acc. no. 1987.142.40.

Figure 3. Image of Dionysus, or possibly Silenus, from Gandhara. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, acc. no. 1979.507.2.

Figure 4. Stair risers from a Gandharan stupa. Cleveland Museum of Art, acc. nos. 30.238–30.330.

Many Gandharan toilet trays show figures apparently linked to the Dionysian tradition (Figure 2). These stone dishes are found in great numbers at the pre-Kushan urban site of Sirkap in Taxila. The lack of wear in the compartments of such dishes seems to indicate that they were not used for cosmetics; scholars have suggested that they were employed for offerings, ritual drinking, or libations.Footnote 25 They are decorated with a variety of figural types, both Indic and non-Indic, and many include images that allude to wine-drinking and intoxication.Footnote 26 The diffusion of Dionysian themes around the beginning of the Common Era among the urbanites of Gandhara, who were strongly Hellenized and had a predilection for Western things, should not surprise us. What is remarkable is that Dionysian elements grew stronger as the Kushans, originally from Central Asia, took control of Gandhara and Buddhism became the dominant inspiration for artistic production.

A terracotta head (Figure 3) dating to the fourth century CE is emblematic of the enduring Dionysian presence in the region. It should be noted that this classical-looking image, possibly representing Silenus, the faithful teacher and companion of Dionysus, was made many centuries after Gandhara’s first encounter with Hellenistic culture. This suggests that the Dionysian tradition, whether assimilated into indigenous Indic cults or existing in its own right, had a long-lasting popularity in the region and became truly local. Further, this Dionysian image was undoubtedly displayed at a Buddhist site. It was probably placed in a shrine flanking the main Buddha image, in a context similar to the one illustrated by the now destroyed chapel V2 at Tepe Shotor in Hadda, in Afghanistan.Footnote 27 The placement of this sculpture in a Buddhist milieu would confirm that Dionysian aspects were systematically incorporated into the Buddhist culture of Gandhara.

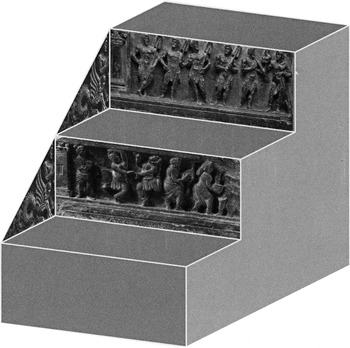

The popularity of Dionysian elements in Gandharan Buddhism is apparent in art produced well before the fourth century CE. Stupas enshrining the sacred relics of the Buddha were decorated with unmistakably Dionysian images as early as the first century CE. Drinking, music-making, and dance were the most recurrent themes depicted on the stair risers leading onto the high plinths of these monuments (Figure 4); devotees would have viewed the images as they ascended to approach the sacred dome (Figure 5). The stair risers appear to be the main figural decorations on early stupas, yet they rarely depict images of the Buddha and his life. Most frequently they portray a row of individuals dressed in different fashions (South Asian, Parthian, or Graeco-Roman) who are engaged in drinking wine, playing music, dancing, and offering flowers. These celebratory scenes are always framed on either side by columns with Corinthian capitals, and the diverse ethnicities of the dancers, musicians, and donors were probably intended to appeal to the multicultural nature of the Gandharan audience.

Figure 5. Drawing showing placement of stair risers. After Kurt Behrendt, The art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007.

The scenes represented in the stair risers illustrated here are unmistakably related to bacchanalia. That ‘hedonistic’ activities such as drinking and dancing were given a prominent position in the decoration of relic-enshrining monuments poses a great dilemma as to the meaning of such scenes within the Buddhist Weltanschauung. What could be the role of these practices in a religion that eschews irrational behaviour and attachment to ephemeral pleasures? Note that the so-called bacchanalian scenes are not represented on the stupa itself but on the steps leading to its base; they do not belong to the world of the Buddha but work as a preamble to it. The Buddha is not represented in these sculptures: bacchanalian scenes are never mixed in with the schist reliefs depicting his life. It appears that images of libations, dancing, and music-making did not relate to the world of the Buddha but rather to that of the devotees.

The images of dancing and drinking on the steps leading onto the stupa were viewed before the actual worship of the relics took place; they highlighted the inception of devotion and marked the passage from secular to sacred. Thus it seems that Gandharan stair risers may have functioned in the same ways as gates and enclosures did at the major pre-Kushan stupas in India. Earlier stupa gates (toranas) in north India were typically embellished with non-Buddhist imagery referring explicitly to nature, abundance, and fertility. They are decorated with yakshas (nature deities), flowers, and purnaghatas (vases of plenty). The same notions of auspiciousness and good beginnings seem to be at the core of the ‘threshold’ iconography of Gandharan Dionysian stair risers, where wine-drinking and dancing refer to abundance and nature. In fact, scholars have suggested that the Dionysian tradition in the north-west was incorporated into the traditionally Indic yaksha cult of nature deities.Footnote 28

The drinkers, musicians, and dancers in Gandharan stair risers are depicted as if in a parade, one following the other, without any overarching narrative framework. It is hard to say whether the scenes represented real celebrations performed by Gandharan Buddhists.Footnote 29 Certainly wine-drinking played an important role in the Buddhist culture of the north-west, and the Buddha supposedly legitimated this practice in the Mulasarvastivada vinaya.Footnote 30 Grapes and wine plants are also represented in Buddhist narrative friezes,Footnote 31 such as the ones excavated from the site of Saidu Sharif in Swat, in Pakistan.Footnote 32 The grapes and vines carved in these schist reliefs are so realistically represented that it is clear that the Buddhists from Gandhara had first-hand knowledge of grapes and their products (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Narrative schist relief from Saidu Sharif, Swat (Gandhara). Museo Nazionale di Arte Orientale, Rome, inv. MNAOR 4152, MAI S 704, deposito IsIAO.

In the relief from Saidu Sharif illustrated here, the vine is not included in the depiction of the Buddha’s life on the lower register but rather appears on the upper register, between two offering scenes linked to the world of Gandharan devotees.Footnote 33 The scene where the vine is represented informs us of the context in which grapes and wine were used in the region. Four figures in this relief are associated with the grapes and vines: the central character is clearly someone of importance, perhaps a royal figure, sitting on a throne with footstool, framed on either side by two figures. He is the recipient of a goat, an animal associated in the Greek world with Dionysus and generally sacrificed to the god, while the attendant on the right holds a cup, perhaps filled with wine. It is possible that we see illustrated here a type of Dionysian ritual involving the offering of a goat and the drinking of wine. This ceremonial scene must have been recognizable to the local Buddhist audience: given the nature of the characters portrayed, it was probably associated with the princely circles of Gandhara.Footnote 34

If some types of Dionysian rituals were practised by the Gandharan elite, then the images of libations, music-making, and dancing represented on stair risers of main Gandharan stupas cannot be explained as simply precursors of the Indic practice of bhakti, a ritual worship well developed in later Hindu traditions that included devotional performances of dance, music, and other activities to reach a sense of unity with the divine. The many wine-drinking figures on Gandharan stair risers wearing Western costumes and carrying vessels such as amphorae and kraters clearly point to re-visitations of Graeco-Roman traditions in this area.

In fact the Greek and Hellenistic worlds offer clues to understanding the Gandharan bacchanalian scenes: the views portrayed on the stair risers are reminiscent of processions that took place in the major Greek cities in conjunction with the various celebrations dedicated to the god Dionysus, celebrations that involved intoxication, wine, and dancing. In particular, such rituals were enacted before dramatic performances in the spring dedicated to the god Dionysus, supposedly the creator of music and drama. Pompai (processions) would regularly occur during the first day of the Anthesteria, the spring festival that took place at the time when the wine produced the previous year was ready for consumption and that celebrated the regeneration of life and nature.Footnote 35 The festivities unfolded through several days, leading to a final dramatic contest: during the second day, the sound of a trumpet would initiate a drinking competition, where wine was consumed from a specific type of cup called choes Footnote 36 and the winner was rewarded with a full wineskin.Footnote 37 Such festivals, celebrated in Greece, were introduced by Alexander the Great to the eastern provinces of the Hellenistic world and were continued there by his successors.Footnote 38 In the Gandharan stair risers now in the Cleveland Museum of Art (Figure 4), we find the key iconographic elements that refer to such Dionysian celebrations: a trumpet player, grapes, wine cups, a wineskin, music-making, and dancing.

All the major Dionysian festivals in Greece – such as the Anthestheria, the Lenaia, the Dionysia Megala celebrated in Athens, and the rural Dionysia Kat’Agrous – culminated with dramatic performances. In the larger Hellenistic world, these dramatic competitions became essential ingredients of the social life of the polis.Footnote 39 Theatre and performances have been historically linked to Dionysus’ cult: much like intoxication, drama creates an alternative mental dimension that does not follow the conventional parameters of reality. Given that theatre was a major component of Dionysian identity, one wonders whether a connection between Dionysian rituals and drama existed in the Gandharan context as well.

Unfortunately, little is known about ancient theatre in the region. Much has been written on the genesis of drama in India and its relationship with Greek theatre,Footnote 40 despite the fact that little evidence survives to quantify the extent of this relationship. Nonetheless, it is clear that the two major dramatic traditions, the Greek and the Indian, had some points of contact in antiquity. For instance, a very intriguing passage from the Bibliotheke (a compendium of Greek mythology from the Hellenistic period) tells us that the god Dionysus organized the first musical recitals after his return from a two-year expedition in India.Footnote 41 Arrian, in his Indika, says that the god Dionysus, having conquered India, introduced into the region specific types of music made with drums and cymbals, and a dance known in Greece as the Satyr dance or Kordax.Footnote 42 Since so many elements of this Western culture appear to have taken root in Gandhara, one would expect that the classical dramatic tradition also reached the north-western regions of the subcontinent along with the Dionysian rituals.

Theatres in the Hellenistic world

There are many references to Dionysian elements and wine in Gandharan art and culture under the Kushans; however, very little evidence survives on the diffusion of the theatre and drama that were so intimately a part of that tradition. We know that, in Hellenistic times, associations of Dionysian technitai (actors), generally attached to a city, travelled widely to perform at important festivals.Footnote 43 In the homeland of Dionysus, the cult of the god as celebrated with wine-drinking and the Athenian theatre were integrally related. Indeed, the thespian performances on the stage had their roots in the choral performances of the Dionysian festival. During the classical period, citizens, including the philosophers, came to the theatre to explore serious questions regarding ethics, the universe, and life on this earth. Using material from ancient Greek mythology, playwrights of the tragedies brought tears to the eyes of the audience. Playwrights in Greece also took on the politics of their polis in comedies, and thus, by participating in the audience response, citizens had an opportunity to express their own attitudes about their political leaders. Both tragedy and comedy thus became an integral part of the Greek cultural tradition and the life of the polis. Comedy, in particular, was based on local affairs, so much so that non-residents often could not understand the jokes.

Therefore, when the whole package of Hellenistic life migrated to more westward Mediterranean areas and eastwards all the way to Afghanistan, could the theatre – not only its architecture but also the performances – have become an integral part of cultural life within the Greek cities established in distant lands? Could the audience of bilingual or multilingual citizens – people who could use Greek when dealing with officials but used local languages when dealing with daily life – understand the nuances of Greek tragedy and comedy?

During the first century CE, many Greek style theatres appeared in Eurasia. The Roman conquest of the entire Mediterranean region, including the Hellenistic north-east, led to the spread of Hellenistic culture further west. In Roman towns, amphitheatres more characteristic of Roman culture continued to be used for sports, but the semicircular, traditional Greek-style theatres remained the stage for dramatic performances. However, in Hellenistic cities, especially under the Pax Romana (first to third centuries CE), the theatre was no longer the civic centre, and actors and playwrights were no longer local. Dramatic performances became professional activities carried out by groups of artists. ‘Dionysiac technitai’ (performing artists) belonged to organizations that took Dionysus as their divine patron and the Hellenistic kings as their secular patrons. This new type of organization first appeared in Athens and then spread to other Hellenized cities, especially those in Ptolemaic Egypt and the Pergamene kingdom, in the north-eastern part of present-day Turkey, east of the Sea of Marmara, and even to more eastern areas controlled by the Seleucids.Footnote 44

During roughly the same period, theatres as emblems of Greek culture invariably appeared in Hellenistic cities all the way from the Mediterranean to the southern bank of the Amu (or the Oxus, as the Greeks called it). Even though there is a lack of evidence of theatrical activities in the Hellenistic cities of Seleucid Iran, due in large part to a lack of archaeological surveys and excavations in that region, the site of Ai Khanoum located further east, is a positive indicator for the presence of Greek theatres in Seleucid territories. This site, which was clearly a major city in Bactria having Hellenistic urban institutions, was also once a territory of the Seleucid empire. Furthermore, the water fountain found at Ai Khanoum, with its basis in a Greek comedy mask, is a strong indication that drama, or at least comedy, was performed there.

For many decades, the voice that has prevailed on Hellenistic theatres located far from the Mediterranean sphere has been that of Michael Ivanovich Rostovtzeff. This famous scholar, who was born in Russia in 1870 and retired from Yale University in 1944, was the leader of the excavation of the caravan city of Dura-Europos. He always doubted that any Greek-style drama was performed in the theatres of Hellenistic caravan cities in Jordan and Syria. There are, indeed, theatre-like structures in several Syrian towns: Palmyra was such a city. However, ‘with a unique constitution, tribal organization, and an all-pervading religious enthusiasm, the presence of a theatre in which the tragedies of Euripides and the comedies of Menander would be played rather than the drama improvised for the court of the Parthian king’ was unthinkable for Rosztovzeff.Footnote 45 In other words, Hellenistic culture could not possible have infiltrated the Arabic culture of Palmyra.

Since Rostovtzeff completed his survey of the caravan cities of the Roman Middle East, which was published in 1932, many more excavations, as well as new research, have indicated that he probably underestimated the impact of the Greek dramatic tradition not only on the peoples of western Asia but even on peoples who lived at the distant edges of the Hellenistic cultural domain. When he was writing his book Caravan cities, for example, Rostovtzeff simply could not believe an excavator’s report of a Greek-style theatre in Palmyra, even though many of the inscriptions gathered from the site indicated that the local people during Roman times had used Greek for official and commercial purposes. The local Aramaic dialect, on the other hand, was still used for ordinary conversations and the transactions of daily life. Now, as one can see through a bird’s-eye view of the excavations at Palmyra, a genuine Greek theatre is located right next to the colonnaded main street. As the most important Roman trading depot in Asia, Palmyra was actually more cosmopolitan than scholars could possibly have realized in the 1930s. Excavations in the necropolis have revealed goods from all over Eurasia, including silk textiles from China and cashmere woollens from Kashmir. Thus one might wonder if the sophisticated trading communities staged and watched dramas in the theatre. Could they use their own language to perform? Could they adopt other topics than those derived from Greek mythology and the life of the Greek polis? Just as many of the temples in Hellenistic cities housed deities from places other than Mount Olympus, the residents in Hellenistic cities, Greeks or locals, could very well have staged dramas – local or foreign in origin – whose themes were related to issues in their own lives.

A discovery from Petra, another caravan city, further demonstrates that the theatres of the Hellenistic caravan cities were real theatres of drama. Working in a sandstone valley between the Red Sea’s Gulf of Aqaba and the Dead Sea, Nabataean Arabs had carved the city’s architectural structures, including a theatre, out of the rock. Most residents, as in Palmyra, were not Greeks, though Greek inscriptions were more prevalent here than in Palmyra.Footnote 46 As in other Hellenized cities, the shrines in Petra housed Greek deities as well as Middle Eastern ones. The most prominent monuments were two obelisks representing their own patron deities, the Sun God and Moon Goddess, which were located on the highest peak, at a place where animal sacrifices were performed.Footnote 47 Meanwhile, Petra boasted all the major institutions of a Hellenistic city, including a huge theatre that could have seated up to 10,000 spectators, about one-third of the city’s population.Footnote 48 Could the Nabataean residents appreciate Greek drama? Despite Rostovtzeff’s lack of confidence in their ability to have appreciated any kind of drama, much less Greek drama, there is good evidence that they did. A high-relief bust of a woman holding a mask has been found in Petra. This woman was definitely an actor, and the sculpture could have been a representation of the Muse Melpomene, the goddess of tragedy.Footnote 49 Thus there is no doubt now that drama of some variety was known to a large theatre audience.

Dionysian worship and Dionysian art did not die out under Roman rule. Rome’s imperial expansion actually re-emphasized the tradition in regions that had once been Hellenized. The site of Zeugma is a good example. It actually consisted of two cities, Seleucia and Apamea, which faced each other across the Euphrates, just inside the bounds of what is now Turkey. Established by the Seleucids, its name can be loosely translated as ‘twin cities’. After Roman expansion into the area, Zeugma became a highly strategic base for holding the Roman position and protecting the commercial centre of Antioch. In the 1990s, archaeologists working at Zeugma discovered a large mosaic pavement in a villa, dated to the late second or early third century CE, which depicts the wedding of Dionysus and Ariadne and includes scenes of wine-drinking and a Dionysian choral performance.Footnote 50 Owing to its strategic position on the Euphrates, the Roman Empire had stationed large garrisons in Zeugma, and the villa where this mosaic was created could have belonged to one of the military commanders or even the governor. Historical documents also indicate that Zeugma hosted large groups of entertainers, including mimes, and sent these troupes to other garrison towns on the Euphrates, such as Dura-Europos.Footnote 51 Thus it is clear that it was not only the kings of the Hellenistic period who acted as patrons for Dionysian art and performances. Their Roman successors appear to have assumed a similar role, at least in their garrison towns.

In Bactria and Gandhara, traces of Dionysian dramatic performances are ubiquitous. As previously mentioned, Ai-Khanoum was a Greek city, and most of the inscriptions discovered there are in Greek. In this setting, there is little doubt that drama was performed in the city’s theatre. Even after waves of nomadic people settled in the region, most people still spoke Greek, although it was not their first language. We have seen that viticulture developed into a mature agriculture in Bactria, Sogdiana, and Ferghana, and wine-drinking and viniculture even crossed the Hindu Kush mountains to Gandhara. In Kapisa, the bronze mask of Dionysus or an old satyr also testifies to the presence of Dionysian art at the Kushan cultural circle. Ashvaghosha, probably the first Indian playwright, certainly wrote his dramas for the stage, and thus some of the first plays performed in India were no doubt Buddhist in theme. The only thing missing in Gandhara is archaeological evidence of a theatre. However, a structure possibly identifiable as a theatre associated with a Buddhist monastery has been discovered at Nagarjunakonda, in the northern part of the Deccan in central India. This theatre is not semicircular like those in the Hellenized cities, but the acoustic effect is good and archaeologists have concluded that it was used for dramatic performances.Footnote 52

Drama and Buddhist art in Gandhara

Despite the evidence discussed above, no theatre structure has been found in the ancient region of Gandhara. However the lack of such archaeological remains in the north-west of the Indian subcontinent does not imply the absence of drama. Temporary structures were probably used for performances, and a back curtain would have been used to define the stage and to indicate the context of the scenes performed, much as described in the Natyasastra. In this Sanskrit canonical source on theatre, the scene backdrop is called yavanika, a word that unmistakably links theatre to yavanas, the Indian appellation given to people of Western, Greek origin.Footnote 53 In the Western dramatic tradition, curtains were originally used to hide the paraskenia (projecting wings of the scene) temporarily. In Hellenistic comedy, a cloth in the background was also conventionally used to suggest that the action took place in interiorsFootnote 54 The use of the backdrop curtain continued in Roman theatre as illustrated by images representing actors performing comedy (Figure 7).Footnote 55

Figure 7. Roman relief depicting actors performing comedy, from Pompeii. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

A beautiful silver cup made in classical vein, probably from first-century CE Gandhara (Figures 8 and 9),Footnote 56 suggests that such conventions were not unknown in north-west India. While the event represented on this vessel is hard to identify, it is unquestionably related to theatrical performances: two emblematic items are the curtain and the mask that was always worn by Greco-Roman actors. Another similar cup fragment from Gandhara, depicting Eros harvesting grapes, a dramatic mask, and a krater for mixing wine,Footnote 57 indicates that themes related to classical theatre appealed to the Gandharan taste, and that the Dionysian connection between wine and drama was well understood in the region.

Figure 8. Silver cup from Gandhara. Private Collection.

Figure 9. Drawing of silver cup from Gandhara in Figure 8 by Marianne Cox.

Curtains and Dionysian themes also appear together on a fragment of a Gandharan schist vessel (Figure 10): here, the curtain functions as a backdrop for two female figures flanking a male character. The female figure on the left, who holds a cup towards the central character, is depicted with a scarf flying overhead: this particular iconographic trait is often found in Roman art in connection with Dionysian characters or with the god himself.Footnote 58 The presence of a dancing figure to the left of the scene described above, suggested by the depiction of a foot and a leg in motion, leaves no doubt about the Dionysian nature of the scene represented. Curtains referencing conventions proper to theatrical performances are also represented, along with images of intoxication and wine, on the enclosure of a Buddhist stupa of Sanghol in Punjab dating to the Kushan period.Footnote 59

Figure 10. Fragment of schist vessel from Gandhara, Metropolitan Museum of Art, acc. no. 1989.18.6.

In Gandhara, the odd combination of wine, Buddhism, and drama is explicated in a very subtle and profound way that goes beyond the simple depiction of bacchanalian scenes on stupa stair risers. It appears that, in the region, drama was instrumental in the creation of a new artistic language employed by the Buddhists. During the first and second centuries CE, Gandharan artists created a large body of narrative sculpture recounting the Buddha’s life story in a chronologically sequential manner, and in this context an anthropomorphic image of the Teacher emerged for the first time (Figure 11). To quote Maurizio Taddei, an eminent historian of Gandharan art, ‘The great diversity of the art of Gandhara in comparison with that of India proper does not consist in its being “narrative” rather than “symbolical”, but in the introduction of a type of narration that can be defined as “historical” and “linear”. This type of narration is absolutely original compared with Indian art.’Footnote 60 If we compare a Gandharan relief depicting a scene from the life of the Buddha with one carved in north India over a hundred years earlier, we will immediately understand the extent to which Gandharan views revolutionized the traditional way of narrating stories through images. The northern Indian relief offers a synchronic view of an event, where the before and after are by no means clear. In Gandhara, on the other hand, the actions unfold in a sequential manner, the protagonists are clearly indicated, and there is no spatial or chronological ambiguity. The Gandharan artists were concerned with representing the life of the Buddha as a closely knit plot. The series of reliefs depicting the various events were affixed on small stupas in the sacred areas in a precise order, beginning with birth-related scenes and ending with the nirvana and distribution of relics.Footnote 61

Figure 11. Narrative reliefs depicting the life of the Buddha from the Sikri Stupa, Lahore Museum.

Taddei observes that the visual repertoire of the Buddha’s life in Gandhara constitutes a complete life cycle, in which the sequence of individual episodes does not break the substantial unity of the story. In this region, the Buddha’s life becomes a spiritual biography, not a simple succession of actions, and Taddei remarks that the ‘earthly temporality of life … is intertwined with the temporality of myth: the pivotal moments of Buddha’s life … are placed in illo tempore, but also in a precise moment of a life that must serve as a model’.Footnote 62 In essence, the conceptual transformation that the life of the Buddha undergoes in Gandharan reliefs is comparable to the one that would take place in a dramatic adaptation of the narration. The parameters that Taddei uses to define the nature of the visual biography of the Buddha in Gandharan reliefs could also function well in the context of theatre. In any drama, the universality of the re-enactment is what triggers a sense of mimesis in the spectators and makes the performance successful.

There is an intrinsic link between Buddhist Gandharan narrative sculpture and theatre: each episode of the life of the Buddha carved on a relief becomes an individual scene of a dramatic piece. Pillars with capitals frame every scene, to define the stage for the action. The whole narrative cycle unfolds like a play on the sculpted panels. The reliefs portraying the Buddha’s life story are arranged around small stupas in chronological order, from the Teacher’s conception to his death and cremation, and, as the devotees walked clockwise around the stupa, the sequential viewing recreated a spatial and temporal progression proper to a theatrical performance.

In the Gandharan narratives the Buddha is, of course, the main actor. He is the protagonist of the events, and the secondary characters appear to be perfectly cast to highlight the moral of the story. The choreographies of the panels also reiterate the idea that the devotee is a spectator: in many stupa reliefs there are viewers looking at the unfolding of the feats from balconies and arcades. This is not to say that Gandharan reliefs represent actual Buddhist plays performed by local actors. What we are trying to argue is that there is a profound dramatic perception behind the creation of Gandharan narrative. The impulse for the genesis of a Buddhist life story that is so rigorously sequential, punctuated, and lacks the symbolic iconicity of Indian art may well come from the tradition of theatre. Ashvaghosha, one of the first known playwrights in the history of Sanskrit theatre, came from Gandhara and was probably affiliated with the court of the Kushan king Kanishka, precisely at the time when Gandharan Buddhist art experienced a tremendous growth.Footnote 63 It has been remarked that Ashvaghosa’s Buddhacarita is very different from other known biographies of the Buddha: in the Buddhacarita, for example, ‘the events are better organized, the tale is more closely knit and, above all, this work unlike the others, is an artistic whole’.Footnote 64 The same can be said for the portrayal of the life of the Buddha in Gandharan narrative sculpture, and it would be hard to imagine that these two traditions, germinating around the same time in Gandhara, developed independently of each other. This is not to say that the sculptures were modelled on the poetic text of the Buddha’s life composed by Ashvaghosha. Scholars have tried to find detailed correspondence between the sequence of events narrated in the Buddhacarita and the ones represented in Gandharan artworks but without success. What we would like to suggest instead is that both the narratives of the Buddha’s life – the poetic and the visual – are expressions of the same dramatic ethos that developed in Gandhara as a result of the long-established presence of Greco-Roman theatrical traditions and Dionysian culture that pervaded the arts of the Kushan period.

Concluding words

Drama may have been used in Gandhara as a popular and accessible medium to explicate the exemplary message of the Buddha to a culturally diverse population of devotees. If it is true that ‘Gandharan art was not the result of Buddhist expansion, but one of the means through which Buddhism expanded – a strong visual propaganda based on powerful economic support’,Footnote 65 then the adoption of drama as a means of expression for the new Buddhist ideology would make perfect sense, especially in a multicultural place, where both the Western dramatic tradition and the Indic one were established. Dionysian elements in Gandhara and their impact on the local artistic tradition have suggested a new venue for the genesis of Buddhist narrative sculpture in the region. The sculptural remains of Gandhara, if examined in parallel with Ashvaghosha’s plays, originally composed in the same region during the Kushan period, indicate that drama developed locally, in conjunction with a strong Dionysian tradition, may have triggered the creation of a poetic, sequential, and cohesive life story of the Buddha in the art of the north-west of India.