1. Introduction

This study takes up the discussion on the emergence of the Modern German periphrastic future construction (henceforth: the werden future), which consists of the auxiliary werden followed by the main verb in the infinitival form. The aim of this paper is to disprove the hypothesis that the werden future developed out of werden + present participle in the 13th century (Weinhold Reference Weinhold1883, Bech Reference Bech1901, Behaghel Reference Behaghel1924, Kleiner Reference Kleiner1925, Erbert Reference Erbert1978, Betten Reference Betten1987, von Polenz Reference Polenz1991). I also discuss the grammatical-ization process that the werden + infinitive construction underwent during the Early New High German period and suggest that this process concluded around the 16th century. The data for this study come from two corpora: Referenzkorpus Mittelhochdeutsch (ReM; the Reference Corpus of Middle High German; Klein et al. Reference Klein, Wegera, Dipper and Wich-Reif2016) and Bonner Frühneuhochdeutschkorpus (FnhdC; the Bonner Corpus of Early New High German).

According to Diewald & Wischer Reference Diewald, Ilse, Diewald, Kahlas-Tarkka and Wischer2013:209, the verb werden “has displayed a high constructional variability” throughout the history of German, and “it has always been used simultaneously in a range of syntactic functions spanning from full verb via copula to auxiliary.” Duden reports that werden is one of the most frequent words in Modern German. In addition to being used in the periphrastic future construction discussed here, it is used in one of the passive forms, the so-called werden passive (werden + past participle). Furthermore, werden can also be found in combinations with a large variety of elements, such as nouns, adjectives, and present participles.

From the historical perspective, werden acquired the capacity of carrying out different syntactic functions throughout the process of “Desemantisierung” [desemantization] that took place in the later years of the Old High German period (9th–10th century) and culminated in the Early New High German period (roughly 14th–17th century; Kotin Reference Kotin2003:17). This process prompted the increase of the use of werden in the passive constructions with a constantly growing number of verbs that appeared in this periphrasis. The desemantization process is also directly involved in the emergence of werden plus an infinitive complement as a future marker (Diewald & Wischer Reference Diewald, Ilse, Diewald, Kahlas-Tarkka and Wischer2013:197).

While there is strong agreement on the emergence of other constructions with werden, such as the werden passive, the question of the origin of the werden future still remains unanswered (Diewald & Smirnova Reference Diewald and Elena2010, Fleischer & Schallert Reference Fleischer and Oliver2011). The scholarship on the werden future has indeed brought forth a number of very diverse and often conflicting hypotheses about its possible source. There is also very little agreement on the period during which this periphrasis emerged. Some scholars argue that it happened in the later years of the Middle High German period (roughly 11th–14th century), while others claim that this periphrasis existed as early as the 9th century (Kotin Reference Kotin2003:135, Diewald & Wischer Reference Diewald, Ilse, Diewald, Kahlas-Tarkka and Wischer2013:215).

In particular, the hypothesis examined here—that werden future (that is, werden + infinitive) developed out of werden + present participle—assumes a diachronic connection between the two periphrastic constructions: According to Bech (Reference Bech1901) and Kleiner (Reference Kleiner1925), in the 13th century, in the Alemannic dialect area the present participle underwent phonetic reduction whereby it lost its ending. As a result, speakers started confusing the present participle with the infinitive and from that point onward began to combine werden with the infinitive. However, as observed by Diewald & Smirnova (Reference Diewald and Elena2010:234), “there is dispute on the question of whether the infinitive complement of werden is an independent development or whether it should be seen as a result of the phonetic reduction of the present participle,” and “the exact details of this development are […] still a matter of dispute.”

In an attempt to resolve this dispute, this paper examines the relationship between the two periphrastic constructions from a diachronic perspective using a corpus analysis. The data from ReM suggest that i) werden + present participle was not the parent construction of werden + infinitive and ii) werden + infinitive was already in use in the 11th and 12th centuries; consequently, the werden future could not have developed out of the werden + present participle construction in the 13th century. At the same time, the data from FnhdC allow one to observe closer the grammaticalization path of this periphrasis.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the research on the combination of werden with present participles and infinitives. Section 3 covers the methodology, that is, the corpora used and the data collection process. The analysis and the discussion of the data are then provided in sections 4 and 5. Section 6 offers a summary of the main findings.

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Werden with Present Participles and the Werden Future

The werden periphrases with present participles, which were first attested in Old High German, have received little attention from the scholarly community compared to other periphrastic constructions, such as werden with past participles (the werden passive) and werden with infinitives (the werden future). The Old High German examples in 1 show werden combined with a present participle. Note that at this point werden is still a copula verb, which has a past and a present form, as in 1a and 1b, respectively.Footnote 1

-

(1)

According to Kotin (Reference Kotin2003:152), the present participle in Old High German had a strong “adjective-like nature” and indicated a long-lasting state. Therefore, present participles were most readily derived from durative verbs, that is, verbs whose semantics do not specify temporal boundaries. The function of werden + present participle was to mark the entering into a particular state or the beginning of an action. Thus, the meaning of ‘starting to speak’ in 1a and ‘starting to be silent’ in 1b is realized through the combination of werden and the present participle forms of the durative verbs speak and be silent.

In Middle High German, the meaning and function of this periphrasis remained unchanged (Kotin Reference Kotin2003:163). In Early New High German, however, the periphrasis with durative verbs gradually vanished. Kotin (Reference Kotin2003:165) links this phenomenon to the simultaneous disappearance of another similar periphrasis: the combination of sîn ‘to be’ and present participles. This construction indicated nonmutative and nonterminative actions, conveying a meaning that was close to the semantics of the main verb in its finite form: habund bist ‘you are having’ versus hâst ‘you have’ or redened war ‘you were speaking’ versus redetest ‘you spoke’. According to Kotin (Reference Kotin2003:166), it is exactly this redundancy in meaning that caused the decline of this periphrasis, which also prompted the disappearance of the constructions of werden + present participle.Footnote 2

Hypotheses on the emergence of the werden future from the periphrases of werden with present participles were formulated first at the beginning of the 20th century (Bech Reference Bech1901, Kleiner Reference Kleiner1925) and supported later on by numerous scholars (Weinhold Reference Weinhold1883, Behaghel Reference Behaghel1924, Erbert 1978, Betten Reference Betten1987, von Polenz Reference Polenz1991). According to these scholars, the periphrasis of werden + infinitive originated from the combination of werden and the present participle. The loss of the ending of the present participle neutralized the difference with the infinitive, and as a result, the infinitive started appearing alongside the present participle in combi-nations with werden. At this point, werden and the infinitive were used as independent verbs, but afterwards the werden + infinitive sequence underwent grammaticalization, and speakers began to use this combi-nation to indicate future events. Meanwhile, the werden + present participle construction disappeared. This process started allegedly in the 13th century in the Low German area, reaching the High German speaking areas shortly thereafter.

Kleiner’s (1925) claim diverges a little from this position. She argues that the periphrases with werden + infinitive originated instead in the Alemannic dialect. These werden + infinitive periphrastic constructions are then the result of the analogy (and “confusion”) between the combinations with the present participle and the dative infinitive, which, in this dialect, was often used without the inflectional ending -de.Footnote 3

2.2. Analogy: Werden Like Modal Verbs

Many scholars have looked at the German modal verbs as the source for the emergence of the werden future: It has been suggested that the werden future emerged by analogy with modal + infinitive constructions. The first account of this type is by Bogner (Reference Bogner1989). He arrives at this conclusion by analyzing the occurrences of werden + infinitive in the FnhdC and by comparing the instances he finds with those of wollen ‘will’, sollen ‘shall’, and müssen ‘must’. Bogner also looks at when these verbs, werden included, were used with temporal or modal readings. He observes that the number of occurrences of werden + infinitive with a temporal reading was around 50 in the first two centuries of the Early New High German period, but that it increased to over 200 two centuries later, especially in the Upper Saxon dialect area. At the same time, the use of the modal verbs with temporal readings significantly declined (Bogner Reference Bogner1989:77). Bogner (Reference Bogner1989) bases his claim only on the instances in Early New High German and identifies the modal verbs with future readings as the model for the werden + infinitive periphrastic construction.

Like Bogner (Reference Bogner1989), Schmid (Reference Schmid2000) considers the modal verb + infinitive construction as the analogical model for the emergence of the werden future. He analyzes a large number of texts from the Upper, Middle, and Low German dialect areas written between the 12th and 15th century and claims that the combination of werden and infinitives is the outcome of linguistic contamination by constructions with the modal verbs. Schmid (Reference Schmid2000) defines contamination as the process by which two semantically related constructions are slowly perceived as being equal and, consequently, start to be used in the same way. Schmid bases his claim on the instances of modal verbs combined with werden that he finds throughout the corpus. He argues that the communicative intent was to collocate the narration in the future (Schmid Reference Schmid2000:13).

Like Bogner (Reference Bogner1989) and Schmid (Reference Schmid2000), Harm (Reference Harm2001:300) also suggests that the emergence of the werden future was the outcome of the analogical association with the modal verbs that had a future reading. According to him, the replacement of present participles with infinitives was triggered by the frequent use of modal verbs with a future reading. Moreover, the werden passive (werden + past participle) in the present tense often had a future or ingressive reading, which further contributed to the perception of werden as the main carrier of the future meaning (Harm Reference Harm2001:304).

It should be noted that in addition to analogy the aspectual semantics of werden are considered a factor. Fritz (Reference Fritz, Frizt and Gloning1997:83) claims that apart from the analogy with the modal verbs, the emergence of the werden future was also influenced by the perfective semantics of the verb werden. He shares the assumptions of Valentin (Reference Valentin1987) about the existence of an aspectual opposition between uuerdan and sîn in Old High German. Fritz claims that, when used alone as the lexical verb meaning ‘become’, werden referred to completed actions and established the temporal frame in which the event in question took place. The feature Grenzbezogenheit [relatedness to a boundary] was central to the semantics of this verb in its earliest occurrences. Between Notker’s time and the beginning of the Middle High German period, werden loses part of its semantics. Consequently, the werden passive starts to behave like the modern Vorgangspassiv [the process passive], acquiring the ability to also describe slow or gradual changes, while werden alone loses part of its perfectivity. According to Fritz (Reference Fritz, Frizt and Gloning1997:88), this process of desemantization comes to an end in Early New High German, when speakers start using werden + infinitive with a future and not aspectual meaning, by analogy with the modal verbs.

2.3. Analogy

Some scholars have argued that the werden future developed from werden + infinitive by analogy with the combination of werden and the infinitival forms of stantan ‘stand’ or biginnan ‘begin’. In his analysis of werden + infinitive, Kotin (Reference Kotin2003) also considers instances from the later years of the Old High German period, when the preterite tense form of werden + infinitive had the function of marking the beginning of an action in the past.Footnote 4 According to Kotin (Reference Kotin2003), this construction was modeled after the Old High German construction with werden followed by stantan ‘stand’ and a similar construction with duginnan ‘begin’ in Gothic. These constructions were used to mark the moment in which an action began.

In Middle High German, werden + infinitive starts to appear in the present tense, with a similar status to that of werden + past participle: At the time, werden + past participle could be considered a bi-verbal construction with both elements still having a relatively large degree of autonomy. In this stage, werden + infinitive in the present tense competed with modal verb constructions, since they could also convey a future-related meaning (Kotin Reference Kotin2003:167). In Middle High German, werden continues to lose its mutative reading—the process that started already in Old High German and was, according to Kotin, one of the prerequisites for its grammaticalization as a future auxiliary (Kotin Reference Kotin2003:172). At the end of the 15th century, Kotin reports relevant changes in the verbal system: The periphrasis with werden in any tense plus present participle and werden in the past tense (preterite or perfect) plus infinitive slowly disappeared. Werden in the present tense plus infinitive becomes the only construction used to express future-related meanings. At the same time, verbs such as sollen and wollen begin to be used only as modal verbs. In Early New High German, werden in the present tense plus infinitive completes its grammaticalization process and makes its way into language use as a periphrastic future construction, or the werden future (Kotin Reference Kotin2003:202).

Another work that considers analogy to be responsible for the emergence of werden as a future auxiliary is Krämer Reference Krämer2005. In her discussion of the emergence of the werden future, she distinguishes between the grammaticalization of werden + infinitive with a future reading and werden + infinitive with a modal reading. The first process started with the combination of werden and the present participle in which werden behaved as a copula verb. Although these claims are similar to those made by Bech (Reference Bech1901), Krämer’s reasons for this development are significantly different. According to Krämer (Reference Krämer2005), the grammatical-ization of werden + infinitive with a future reading occurs in two steps. During the first step, the infinitive replaces the present participle through analogical association with the Old High German biginnan ‘begin’ + infinitive construction. Such analogy was motivated by the two constructions sharing a clear ingressive reading. At the beginning of this process, werden + present participle and werden + infinitive coexist, and in both constructions werden still behaves as a copula. In the second step, the periphrasis with the infinitive is reanalyzed, and werden acquires its status as an auxiliary for the expression of future tense. Once the future construction is fully established, the modal reading arises. At the same time, the combination of werden plus present participle completely disappears (Krämer Reference Krämer2005:92). Krämer summarizes the development of werden as follows:

-

(2)

The most recent account to date on the werden future is by Diewald & Wischer (2013). In this study, the authors compare the future auxiliary “candidates” in Old English and Old High German. Other than werdan, Old High German candidates included verbs such as wellan ‘want’ and sculan ‘should’. These latter verbs occurred frequently and were very often used with future implications; yet they were never suitable candidates for such a role because of their semantic components that involved volition or obligation. Conversely, werdan could grammaticalize into a future auxiliary because of its dominant ingressive meaning, which made it compatible with predicates of any kind. Additionally, Diewald & Wischer (2013:209) point out the following:

[T]hroughout the history of German, werden has displayed a high constructional variability. It has always been used simultaneously in a range of syntactic functions spanning from full verb via copula to auxiliary.

Diewald & Wischer (Reference Diewald, Ilse, Diewald, Kahlas-Tarkka and Wischer2013:215) also report some instances of werden in the present tense combined with an infinitive from the Gospel Harmony by Otfrid, contradicting in part what is claimed by Kotin (Reference Kotin2003:135), who stated that such a combination in Old High German could appear only with werden in the past tense.

2.4. The Werden Future as a Product of Language Contact

Other scholars depart from the aforementioned hypotheses, arguing that the werden future constructions in German emerged as a result of language contact. Leiss (Reference Leiss1985:295) identifies instances of language contact between German and Czech during the so-called Ostkolonisierung [east colonization] between the 12th and 14th centuries as the main source for the werden future. Specifically, the construction with budo ‘be’ plus infinitive, which was used in Czech to indicate forthcoming events, functioned as the model for the formation of the werden future in German. Leiss bases her hypothesis on two different factors. First, the Czech construction, she argues, was older than its German counterpart with werden. Second, werden + infinitive originated in the eastern Middle German dialect, which was spoken in an area close to where Czech was spoken. As a result, several episodes of language contact between Czech and German triggered the formation of the werden future, based on the budo plus infinitive combination.Footnote 5

Diewald & Habermann (Reference Diewald, Mechthild, Leuschner, Mortelmans and De Groodt2005) also offer an account on the emergence of the werden future and suggest that “werden erst durch den Sprachkontakt mit dem Lateinischen zur systematischen Futurmarkierung des Deutschen wurde” [werden became the systematic future marker in German first through contact with Latin] (p. 241). According to Diewald & Habermann (2005), this construction evolved between the later years of the Middle High German period and the beginning of the Early New High German period. Although they acknowledge the existence of werden + infinitive in Old High German, they identify the time frame between the 14th and the 16th centuries as the relevant stage in which this structure gained its status as future tense marker. They identify two steps in the grammaticalization process of this construction. The first one is characterized by a succession of internal linguistic phenomena such as analogy. Diewald & Habermann (Reference Diewald, Mechthild, Leuschner, Mortelmans and De Groodt2005:245) define this first step as a process that “involves attraction of extant forms to already existing structures, hence generalization.” Citing Bybee et al. Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994, they point out that periphrastic future constructions normally emerge from deontic modals. For example, lexemes that express desire, wish or obligation are traditionally recognized sources for the development of future tense forms. In contrast, the emergence of a periphrastic future from a lexeme with perfective semantics, such as werden, is very rare (Diewald & Habermann Reference Diewald, Mechthild, Leuschner, Mortelmans and De Groodt2005:278).

Nonetheless, the authors list different factors that contributed to the emergence of werden as an auxiliary with a future temporal reference. First, the intrinsic semantics of werden itself made it a suitable candidate for this purpose. Second, werden frequently appeared in different types of constructions, showing a large “konstruktionelle Variabilität” [constructional variability]. Third, werden + infinitive could strengthen its future meaning through the analogical integration of these constructions into the small group of ingressive verbs. However, these factors alone do not suffice to fully explain the spread of werden + infinitive as a future marker. According to Diewald & Habermann (2005:239), it was language contact with Latin that played a key role in the emergence of the werden future.

To summarize, this overview of the scholarship on the werden future has highlighted the large variety of theories and hypotheses on both the meaning and the origins of this construction that have been put forward by the scientific community. Yet despite this amount of research, there is still little agreement around the emergence of the werden future and, consequently, the question about its origins still remains unanswered today (Fleischer & Schallert 2011). To resolve the uncertainty around this construction, I conducted a diachronic corpus linguistic analysis of werden + present participle and werden + infinitive—the two constructions that could have potentially lead to the emergence of the werden future. The goal of the analysis is to re-examine the hypothesis according to which the werden future emerged from the werden + present participle construction in the 13th century (Bech Reference Bech1901, Kleiner Reference Kleiner1925). In the next section, I discuss the methodology used to collect and analyze the data.

3. Methodology: The Corpora and Data Selection

This section discusses the methodology of data selection and extraction. The data consist of the instances of werden + present participle and werden + infinitive found in a total of 51 texts from Middle and Early New High German. The results are presented and discussed separately for Middle High German and Early New High German in sections 4 and 5, respectively. The texts from which I have collected the data come from two different annotated online corpora: Referenzkorpus Mittelhochdeutsch (ReM; the Reference Corpus of Middle High German) and Bonner Frühneuhochdeutschkorpus (FnhdC; the Bonner Corpus of Early New High German).

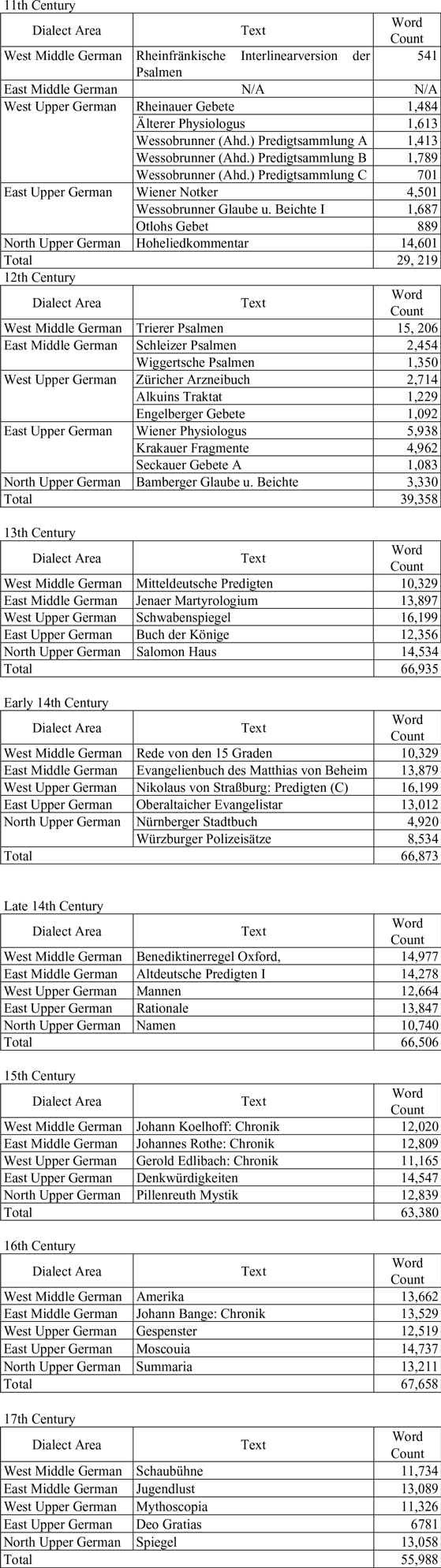

ReM consists of three different subcorpora: Kölner Korpus hessisch-thüringischer Texte (the Cologne Corpus of Hessian-Thuringian Texts), Bonner Korpus mitteldeutscher Texte (the Bonn Corpus of Middle German Texts), and Bochumer Mittelhochdeutschkorpus (BoMiKo; the Bochum Middle High German Corpus). For the Middle High German portion of this study, a total of 30 texts from ReM were selected that cover the entire Middle High German period (the second half of the 11th–early 14th century) and five different dialectal areas (West Middle German, East Middle German, West Upper German, East Upper German, and North Upper German), which cover a vast geographical area. I selected an average number of two texts for each century and dialect. The selected writings comprise mostly religious and legal texts, which allows this project to concentrate on texts with similar topics and exclude poetry. The total word count for Middle High German is 202,385.

For the Early New High German portion of this study, 20 texts from FnhdC were selected that cover the period from the late 14th century to the 17th century. The selection encompasses religious as well as legal prose texts, together with other text types. Like the selection for the Middle High German portion of the study, the selected Early New High German texts come from five different dialect areas: West Middle German, East Middle German, West Upper German, East Upper German, and North Upper German. The total number of words for Early New High German is 253,559. The raw and normalized frequencies of werden and the elements with which it is combined are discussed at the end of the section. The list of texts can be found in Appendix.

For the purposes of this study, two different databases were created—for Middle High German and for Early New High German—and all the instances of werden found in the selected texts were assigned accordingly. The two databases contain all the tokens of [werden + infinitives] and [werden + present participle].

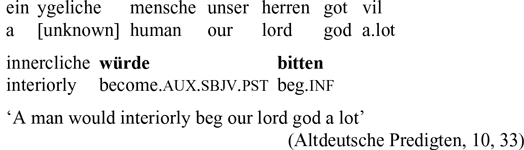

The data also show the tenses in which werden was used (present, preterite, or past perfect) independently of the mood (indicative or subjunctive). The data are presented in detailed charts and then discussed. The analysis did not include sentences with werden in which the annotations of one of the elements were missing, as shown in example 3. The missing annotation for the words that are not translated are displayed as [!] in ReM and as “unbekannt” [unknown] in FnhdC.

-

(3)

In such examples, it is impossible to determine whether werden is combined with an infinitive, a past participle or a noun, and so they are not included in the data. In the next section, I offer a detailed account of the attestations of the verb werden found in the Middle High German and Early New High German corpora.

4. Middle High German: The Origins of the Werden Future

4.1. Results

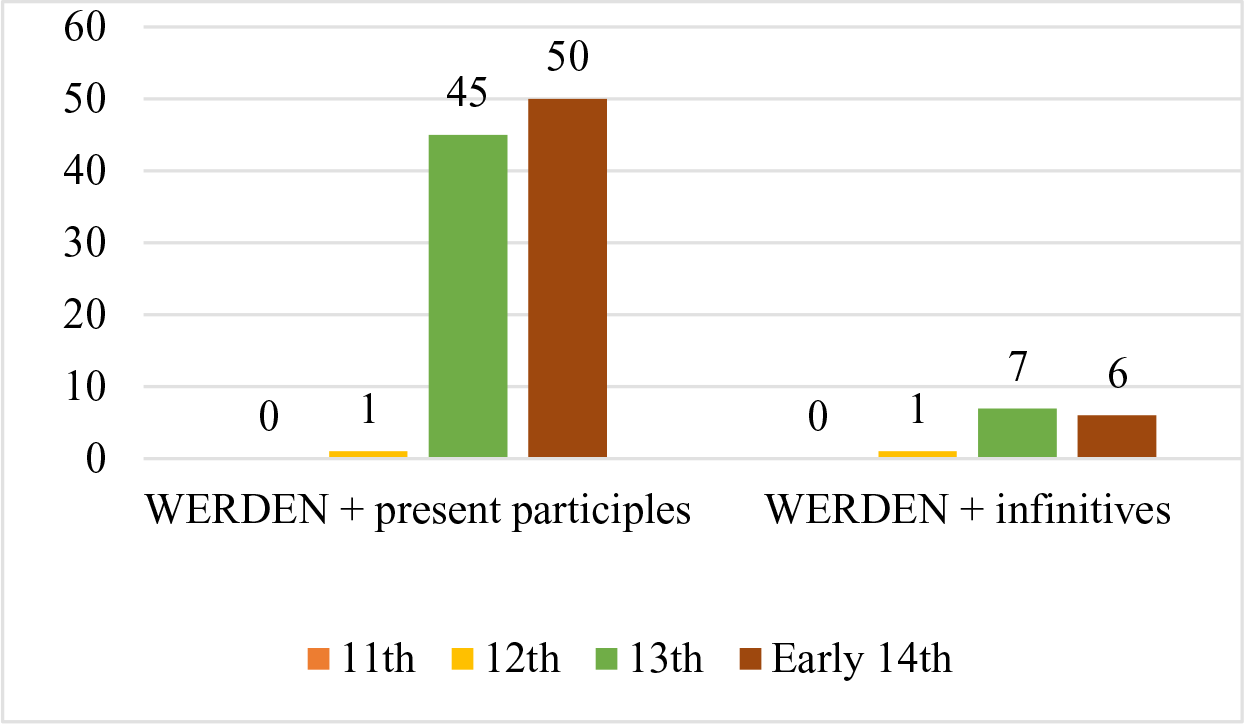

A total of 110 instances of werden with present participles and werden with infinitives were analyzed. Figure 1 shows the raw and normalized (per 10,000 words) frequencies of the instances of werden in Middle High German.

Figure 1. Raw and normalized frequencies of the instances of werden with present participles and infinitives.

The majority of the instances of werden occurred with present participles, with a total of 96 occurrences. Of these instances, 48 were in the present tense, 47 in the preterite, and 1 in the present perfect. There was a total of 14 instances with infinitives, and in all of them werden was used in the present tense. The ability of werden to appear in different tense forms is discussed in more detail in section 5.

Figures 2 and 3 show the raw and normalized frequencies of the distribution of the instances of werden for each century.

Figure 2. Raw frequency per century of the instances of werden with present participles and infinitives.

Figure 3. Normalized frequency per century of the instances of werden with present participles and infinitives.

Many instances of werden with present participles date from the early 14th century, followed by the 13th and the 12th centuries. The number of instances of werden with infinitives is almost the same in the 13th and early 14th centuries.

The texts used in this study yielded only one instance of werden + infinitive from the 12th century and no instances of werden with either infinitive or present participle from the 11th century. Note, however, that I had only a few texts to work with from the 11th century, which might explain the absence of werden + infinitive in my data. As discussed in the literature review, werden + infinitive was attested as early as the Old High German period (Kotin Reference Kotin2003, Krämer Reference Krämer2005, Diewald & Wischer Reference Diewald, Ilse, Diewald, Kahlas-Tarkka and Wischer2013), which makes me believe that the construction was already in use in the 11th and 12th centuries.

4.2. Discussion

While no instances of werden with either present participles or infinites were found in the 11th century, the texts from the 12th to the early 14th century all contained attestations of both these periphrases. In the 12th century, werden was found once in combination with a present participle, as in 4a, and once with a verb in the infinitive form, as in 4b. Note that in these examples, werden already functions as an auxiliary.

-

(4)

Note also the difference in the aspectual interpretation between 4a and 4b, which stems from the aspectual properties of the present participle and the infinitive, as discussed in section 2.1. Unlike the present participle, the infinitive is more “verb-like” in nature: It does not require the event in question to be long-lasting or to have temporal boundaries, and could be easily derived from any type of verb, not only from durative verbs. This is exemplified in 4b: Warn is not a durative verb, and the combination of werden and the infinitive is most naturally interpreted as referring to a future event.

The examples in 4 are thus extremely interesting when considered in relation to the question about the time and the source from which the German werden future emerged. First, werden + present participle and werden + infinitive are both found in Old High German (Diewald & Wischer 2013) and in the first two centuries of Middle High German. The coexistence of these constructions during this period suggests that the combination with the present participle was probably not the source of the development of the werden future, which allegedly took place in the 13th century. Second, the aspectual properties of infinitival verbs make werden + infinitive a more likely candidate for a periphrastic future construction: In 4b, werden can position the time of the action in the future, so one can say that the meaning expressed here resembles the future as it is known today.

The two constructions continue to coexist well into the Middle High German period. In the texts from the 13th century, there are several instances of werden combined with present participles, as in 5a, and with infinitives, as in 5b.

-

(5)

The examples in 5 also show that the same verbs could occur with werden as present participles and infinitives—the verb sehen ‘see’ in this case. More specifically, in the attestations with present participles, werden combined with atelic verbs, that is, verbs that do not specify temporal boundaries, such as sehen ‘see’, hören ‘hear’, wundern ‘wonder’, sprechen ‘speak’, weinen ‘cry’, herrschen ‘rule’, and streiten ‘fight’ (see Schumacher Reference Schumacher2005:151 and references there). A comparison with the instances of werden and verbs in their infinitival forms reveals a similar distribution: Among the verbs found in the infinitival form, there are verbs such as sehen ‘see’ and führen ‘lead’. One exception is the telic verb vahende ‘catch’, as in 5b.

The constructions with present participles and with infinitives found in the early 14th century have a similar distribution to the ones observed in the previous centuries. The periphrases with present participles conveyed the meaning of entering into the particular event or state expressed by the verb, as shown in 6. Note that the auxiliary in 6b is in the past tense, which becomes relevant in section 5, where I discuss the grammaticalization process.

-

(6)

The instances with infinitives found in the 14th century express a comparable meaning to the same type of constructions in Modern German, as shown in the examples in 7.

-

(7)

In the early 14th century, the verbs found in the present participle were both atelic, such as sehen ‘see’, beten ‘pray’, hassen ‘hate’, and achten ‘respect/pay attention to something’, and telic, such as kreuzigen ‘crucify’, verdammen ‘condemn’, and fangen ‘catch’. The verbs found in the infinitive were also both atelic, such as hassen ‘hate’ and lachen ‘laugh’, and telic, such as erkennen ‘recognize’ and kaufen ‘buy’:

-

(8)

This overlap between the types of verbs that could appear in werden + present participle and werden + infinitive in the early 14th century confirms the trends observed in the 12th and especially the 13th century. The question is why the two constructions coexisted in the language for such a long time. Kotin (Reference Kotin2003:162) refers to werden + present participle and werden + infinitive as “twin constructions” in the sense that they looked very similar but served different purposes. He argues that speakers chose one or the other depending on how they wished to describe the event in question. As discussed in the review of the literature, in Old and Middle High German, the present participle had a strong “adjective-like nature” and indicated a long-lasting event or state (Kotin Reference Kotin2003:152). Conversely, the infinitive was more “verb-like” than the present participle, and the combination of werden and the infinitive was similar to werden + past participle (the werden passive), in that the two elements clearly had a “verb-like nature” (Kotin Reference Kotin2003:160).

The different properties of the present participle and the infinitive determined the aspectual interpretation of each construction. Combined with werden, the present participle indicated the beginning of a particular event or entering into a particular state for an indefinite amount of time, independently of the type of its base verb—durative or resultative (Kotin Reference Kotin2003:152). Thus, werden + present participle always denoted temporally unbounded events regardless of whether or not the main verb was atelic or telic. In contrast, when infinitives combined with werden, the aspectual properties of their base verb mattered: As the infinitive did not impose any aspectual restrictions, durative verbs kept their temporal indefiniteness, whereas resultative verbs retained their telic aspectual features (Kotin Reference Kotin2003:152). Thus, werden + infinitive described either unbounded or bounded events, depending on the main verb. Based on this difference, Kotin (Reference Kotin2003) argues that werden with present participles and werden with infinitive verbs were not related through a parental relationship; they originated from different sources and coexisted in the language for a long time until the periphrasis with the present participle disappeared.

German speakers in the 12th– early 14th century seem to have been aware of the aspectual differences between werden + present participle and werden + infinitive. As claimed by Eve Clark, “when speakers choose an expression, they do so because they mean something that they wouldn’t mean by choosing an alternative expression” (Clark Reference Clark and MacWhinney1990:417). The occurrence of the same verbs in both werden constructions—with present participles and infinitives—as shown in 5 reveals that speakers were aware of the differences between these two periphrases.

To summarize, a total of 110 instances of werden with the present participles and the infinitive were found in the Middle High German corpus. The data from this period provided insightful information on the use of the werden constructions with present participles and infinitives, and shed light onto the possible origins of the Modern German werden future. In particular, the data suggest that, contrary to previous analyses (such as Bech Reference Bech1901 and Kleiner Reference Kleiner1925), werden + present participle was not the source from which the werden future emerged. First, both these periphrases were attested in Old High German (Kotin Reference Kotin2003). Second, the texts from the 12th century had attestations of these periphrases, suggesting that the combination of werden with infinitives was well established in this period or even earlier. Finally, in the texts from the 13th and early 14th century, these constructions were used with the same or similar types of verbs, and in analogous contexts. These findings seem to support the analyses of scholars such as Kotin (Reference Kotin2003), who claimed that werden + present participle and werden + infinitive were “twin constructions” rather than being genetically related by a parental relationship.

5. Early New High German: The Grammaticalization Path

Using corpus data from FnhdC, in this section I discuss further development of werden + present participle and werden + infinitive and address the grammaticalization process that the latter underwent during the Early New High German period. The data show that at the beginning of this period, werden in werden + infinitive could still appear in the past tense in the indicative mood (preterite and perfect). Later on, however, werden lost this ability as past tense became incompatible with the future meaning of the construction. The data also suggest that the grammaticalization process concluded around the 16th century.

5.1. Results

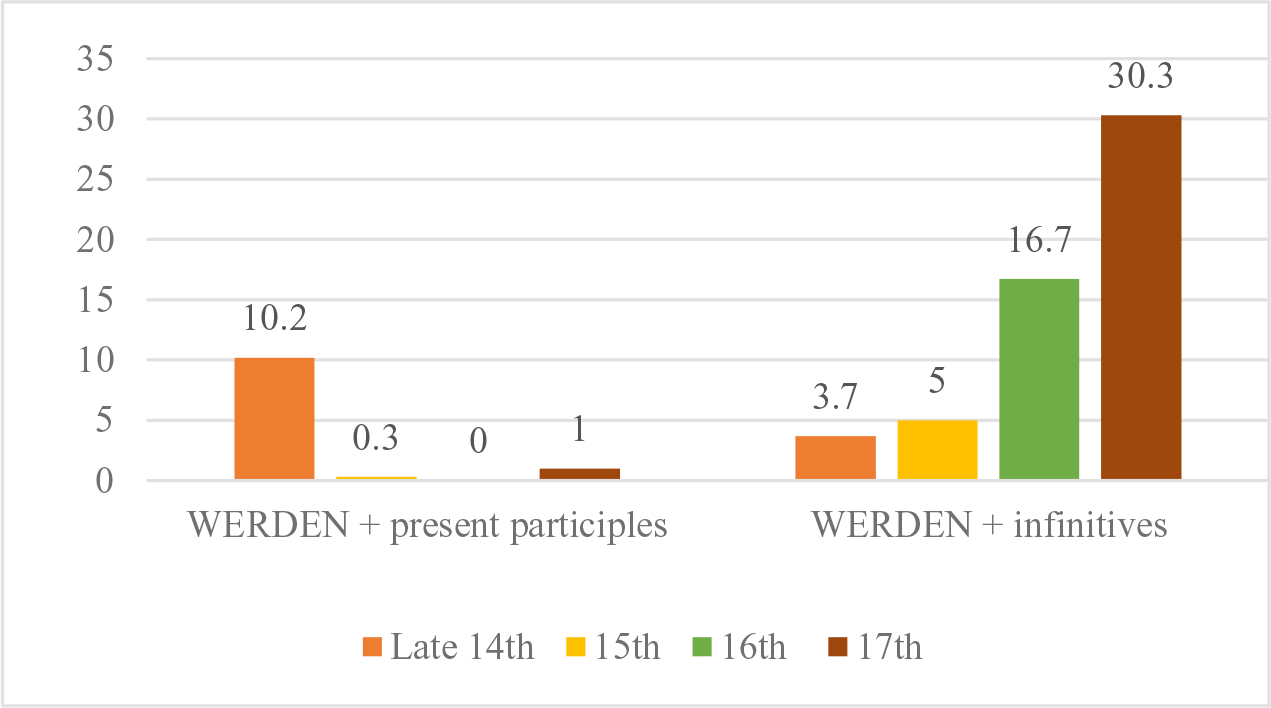

A total of 410 instances of werden with present participles and werden with infinitives from FnhdC were analyzed. shows the raw and normalized frequencies of the instances of werden in Early New High German.

Figure 4. Raw and normalized frequencies of the instances of werden with present participles and infinitives.

Contrary to what was found in Middle High German, in Early New High German the majority of the instances of werden were with infinitives, with a total of 339 occurrences. Note that of these instances, 269 had werden in the present tense, whereas 70 had werden in the preterite, which is a construction that not exist today. It is also during this period that werden + infinitive is attested for the first time in the subjunctive mood: Among the instances with werden in the present tense, 241 were in the indicative mood, while the remaining 28 were in the subjunctive mood. Among the instances with werden in the preterite, five were in the indicative mood, while the rest were in the subjunctive.

There was a total of 71 instances of werden + present participles, 45 with werden in the present tense, 25 in the preterite, and one in the present perfect. Figures 5 and 6 show the raw and normalized frequencies of the distribution of the instances of werden for each century. A significant portion of the instances of werden with infinitives was found in the last two centuries of the Early New High German period (that is, the 16th and 17th centuries). In contrast, the highest number of instances with present participles comes from the late 14th century, whereas in the following centuries the number of occurrences is extremely low. These results indicate that while werden + infinitive was on the rise, werden + present participle was gradually disappearing during the same period.

Figure 5. Raw frequency per century of the instances of werden with present participles and infinitives.

Figure 6. Normalized frequency per century of the instances of werden with present participles and infinitives.

5.2. Discussion

The data from FnhdC show that at the beginning of the Early New High German period, werden in both constructions could appear in past tense (preterite and present perfect). These observations show that at that point, werden was not yet a future auxiliary. The data from the second half of the 14th century still show a high number of werden + present participle constructions, even though their occurrence begins to decline later. The examples of werden + present participle in 9 show werden in present tense, whereas in 10 it appears in past tense.

-

(9)

-

(10)

The combination of werden with the present participle appears to have kept a meaning similar to the same type of constructions from the 13th and the first half of the 14th century.

As for werden + infinitive, the data contained a total of 25 instances of this construction, including three instances with werden in past tense, as in 12.

-

(11)

-

(12)

It should be mentioned that some data may potentially call into question the infinitival status of sehen in 12: In the same period, the sequence gelosen sehen appears in perfect constructions with haben, as in het gelosen sehen lit. ‘has calm seen’ (Mannen, 13,30). In Old and Middle High German, some verbs did not take the prefix ge- in the past participle, and so the form sehen in 12 could potentially be a past participle and not an infinitive. Note, however, that verbs without the prefix ge- in the past participle were telic and had perfective semantics, such as bringen ‘bring’ and finden ‘find’ (Kotin Reference Kotin2003:239). In contrast, sehen is an atelic verb, which denotes an ongoing state. Further, 12b also contains the second infinitive bevinden ‘find’, which is another complement of werden joined with sehen by und ‘and’.Footnote 6 Assuming that only elements of the same category may be conjoined by und, it is reasonable to conclude that sehen in this case appears in its infinitival form and that the entire construction therefore is an instance of werden (in the past tense) + infinitive.

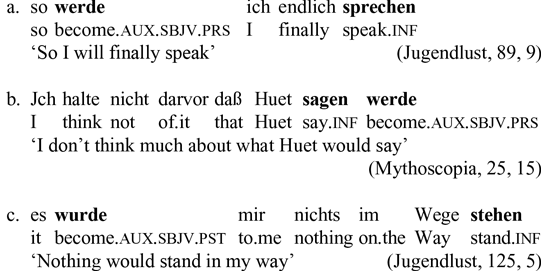

In the second half of the 14th century (that is, at the beginning of the Early New High German period), periphrases with werden in the subjunctive mood + infinitive were first attested (Smirnova Reference Smirnova2006:269). These constructions were used to express desire or to describe a hypothetical situation and appeared in subordinate clauses, with the main clause being in the past tense (Smirnova Reference Smirnova2006:271):

-

(13)

The texts from the 15th century begin to show a different distribution of the constructions with the present participle and the infinitive. Only two attestations of werden combined with the present participle were found. One of them is shown in 14.

-

(14)

In 14, the verb werden appears with two present participles that function as adjectives describing wreck ‘works’. This example shows that the present participle still keeps its adjective-like nature, which was observed in the examples found so far and which are preserved in Modern German.

In contrast, the occurrence of werden combined with infinitives during the same period is much higher: Thirty-two attestations were found. Two examples are given in 15.

-

(15)

Note that at this point, the majority of the instances with werden in the past combined with the infinitive (19 in total) were in the subjunctive mood, with only two forms still in the indicative mood, as shown in 16. Eventually, werden could no longer appear in the preterite when combined with an infinitival form, which is a clear sign of its grammaticalization status.

-

(16)

Yet these two occurrences of the preterite werden + infinitive seem to suggest that by the 15th century, werden had not yet lost its mutative meaning that it had in Old and Middle High German. Werden was, indeed, still relatively autonomous at this stage, and, in the preterite, could be combined with verbs in their infinitive forms. In this case, this periphrasis had the capacity to convey the onset of a new state that was the result of previous actions (Smirnova Reference Smirnova2006:246). Expressing the fact that the subject has entered into the new state of burning in 16 seems to be the direct consequence of the previous action of falling. The use of the infinitive combined with werden in the preterite signals that the subject entered the new state in the past because the action causing this new state also took place in the past.

In the texts from the 16th century, no instances of werden with present participles were found, whereas there was a remarkable number of combinations of werden with verbs in the infinitive (113 in total). While all the forms in past tense (9 in total) were in the subjunctive mood, among those in the present (104 in total), 79 were in the indicative mood, as shown in 17.

-

(17)

The examples in 17 give some relevant information about the status of this periphrasis at that time. Example 17a shows that werden + infinitive is already very similar semantically to the werden future in Modern German. Example 17b, in which there are two forms of werden (one as an auxiliary and one as a copula verb), shows that this verb is probably losing part of its original meaning and autonomy. According to Bybee (Reference Bybee and Tomasello2003:7), with repetition, sequences of units that were previously independent come to be processed as a single unit. This repackaging has two consequences: First, the identity of the components is gradually lost, and second, the entire unit begins to reduce in form.

The increased frequency of the werden + infinitive construction that expresses future meaning is presumably influencing the way this combination is perceived in the language, namely, it is gradually reanalyzed as a single unit rather than a combination of two independent verbs. The direct consequence of this reanalysis is the gradual loss of the original autonomy and meaning that made it possible for the past tense form of werden to be used with infinitives; that is, werden has been undergoing the desemantization process (see Kotin Reference Kotin2003), which probably reaches its final stage in the 16th century.

Moving on to the 17th century, the data from this period show only one instance of werden in present perfect combined with a present participle in one afinite construction (Breitbarth Reference Breitbarth, Cornips and Doetjes2004, Reference Breitbarth2005), as shown in 18. The present perfect had also reached the final stage of its grammaticalization by this period (Concu Reference Concu2016).

-

(18)

Data from the 17th century contain the highest number of werden + infinitive constructions found so far (170 in total). The majority of instances of werden in the present tense were in the indicative mood, as shown in 19a, with only three instances being in the subjunctive mood, such as the one in 19b. In contrast, all the attestations of werden in the past tense were in the subjunctive, as shown in 19c. There were no instances of werden in the preterite indicative followed by an infinitive.

-

(19)

The occurrence of werden + infinitive in the past subjunctive on one hand, and the absence of instances of werden + infinitive in the past indicative on the other indicates that werden + infinitive has reached the end of its grammaticalization process as a future marker: It went from the old aspectual meaning to the new temporal one (Kotin Reference Kotin2003:169). Once this development is completed, the use of werden in the past indicative is incompatible with its newly acquired function of a future auxiliary. As a consequence, the combination of werden in the preterite and the infinitive slowly disappears from the language (Smirnova Reference Smirnova2006:261).

Werden + present participle had also almost disappeared by this time. No instances of this periphrasis were found in the previous century, and only one was found in the 17th century.

To summarize, a total of 410 forms of werden were analyzed in the texts from Early New High German. While the second half of the 14th century was the period with the larger number of attestations of werden with the present participle, the 17th century was the one with the highest number of combinations of werden with infinitives. The data selected from FnhdC contained instances of werden in the past tense with infinitives, and these occurrences suggest that this verb, at least until the end of the 14th century, had a relatively autonomous status, which was first observed in the Middle High German data. The 16th century had the very first attestation of two forms of the verb werden in the same predicate—the first one used as an auxiliary, and the second one as an infinitive. This instance provided some indication that the periphrastic werden future was on the grammaticalization path, and that its grammaticalization was probably reaching its final stage at that time.

6. Conclusion

The goal of this study was to track the historical development of the verb werden in Middle and Early New High German in order to explain the emergence of the werden future. This study has critically examined the hypothesis that the werden construction with infinitives derived from the combination of werden and the present participle in the 13th century (Weinhold Reference Weinhold1883, Bech Reference Bech1901, Behaghel Reference Behaghel1924, Kleiner Reference Kleiner1925, Erbert Reference Erbert1978, Betten Reference Betten1987, von Polenz Reference Polenz1991). Hence, I focused on the relationship between the constructions with werden and the present participle and werden and the infinitive in Middle and Early New High German. The diachronic corpus analysis carried out in this study showed that these constructions could be found in the same or similar communicative contexts as early as the 12th century. These findings suggest that these constructions were already well established in the language, probably even before the 12th century. These results rule out a possible parental relationship between these two constructions and provide support for Kotin’s (2003) position: Werden with the present participle and werden with the infinitive were “twin constructions.”

Furthermore, the analysis has also provided insight into the period in which the werden future emerged. The occurrences found in Middle High German implied that this construction emerged earlier than the 13th century, as scholars such as Diewald & Wischer (2013) have suggested. The instances found in Early New High German also offered insightful information on the grammaticalization process of this construction, indicating that it possibly culminated in the 16th century. In sum, the findings of this study have ruled out werden together with the present participle as the origin of werden future. The factors leading to the development of the latter construction still require further investigation (for example, by analogy with modal verbs, stantan and biginnan).

APPENDIX