1. Introduction

The early runic material is especially interesting as it preserves what has traditionally been known as Proto-Norse (Urnordisch), the only early Germanic dialect where the vowels produced before glides under Sievers’ Law are attested in their original forms. Gothic and the later dialects already feature so much phonological development as to obscure the underlying alternations of -j- ~ -ij- and -w- ~ -uw- that are expected to occur under Sievers’ Law. As Eduard Sievers (Reference Sievers1878:129) himself put it, projecting alternations such as those seen in Gothic harjis ‘army’ (< + harja-) and hairdeis ‘shepherd’ (< + herdija-) back to Proto-Indo-European, the underlying segment is realized as a “consonant nach kurzer, vocal nach langer silbe.”Footnote 1 Any violations of Sievers’ Law would be expected to be particularly clear in early runic inscriptions.

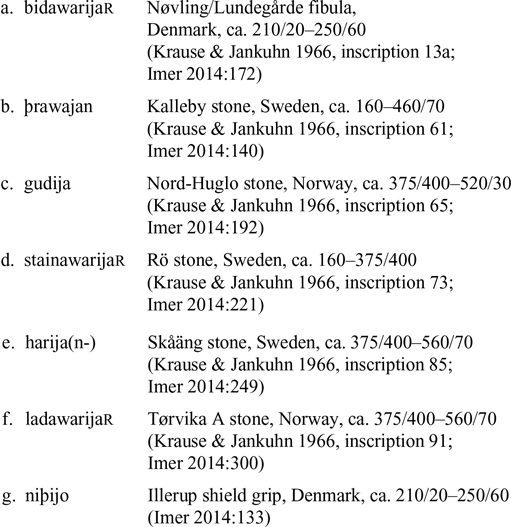

Several instances of spellings in older runic inscriptions are widely considered to represent exceptions to Sievers’ Law. Elmer Antonsen (Reference Antonsen1975:17) argued that there were seven exceptions, Otto Springer (Reference Springer1975) allowed five, Martin Syrett (Reference Syrett1994:184–187) recognized six or possibly seven “best examples,” Marc Pierce (Reference Pierce2002:158) seven, and Michael Schulte (Reference Schulte2018:77–81) at least five. Antonsen (Reference Antonsen1975:17) included the Gallehus inscription’s <holtijar> (Krause & Jankuhn Reference Krause and Jankuhn1966, inscription 43; Imer Reference Imer2014:88) in his list, whereas Pierce (Reference Pierce2002:149) takes the Vimose plane’s <talijo> (Krause & Jankuhn Reference Krause and Jankuhn1966, inscription 25; Imer Reference Imer2014:324) and the Stenstad stone’s <igijon> (Krause & Jankuhn Reference Krause and Jankuhn1966, inscription 81; Imer Reference Imer2014:263) to represent exceptions to Sievers’ Law. However, Antonsen’s inclusion of <holtijar> has been widely rejected, and <talijo> and <igijon> have usually been explained as unexpected spellings for tal(g)ijō ‘wood plane’ and I(n)gijōn ‘Ingijo’s’, respectively. It is also notable that since the publication of the key works by Krause & Jankuhn (Reference Krause and Jankuhn1966) and Antonsen (Reference Antonsen1975) a significant number of early runic texts have been discovered that preserve forms in which Sievers’ Law clearly applies; yet only one example has been proposed (by Syrett) to be an addition to the lists of possible exceptions adduced since the 1970s. Syrett’s (Reference Syrett1994:185) examples taken from Krause & Jankuhn (Reference Krause and Jankuhn1966) appear in 1a–f and his possible, more recently discovered example is 1g. The rune transcribed by scholars such as Syrett as <r> originally signified Germanic +/z/, but it is not clear when the rhotacism took place.

(1)

It is the form that appears on the Skåäng stone, rendered as <harija(n-)> by Syrett, that has proved the most important in the literature as it was the first of the early runic inscriptions to be analyzed as featuring an exception to Sievers’ Law (von Grienberger Reference Grienberger1906:110). The other examples were isolated subsequent to the widespread acceptance of a violation in Sievers’ Law occurring in the Skåäng inscription.

Yet the treatments of the inscriptions given in Syrett’s list often seem to suffer from what Lena Peterson (Reference Peterson and Düwel1998:573) has criticized as a form of canonicity. Canonicity is a notion originally associated with Biblical interpretation; it occurs when a particular written work, interpretation or approach is claimed to be established by appeal to tradition. Rather than looking at early runic texts through critical eyes—or even in terms of the development of the older historiography—interpretations recorded in Wolfgang Krause’s 1966 edition of the older inscriptions are often repeated in runological scholarship without first being subject to a full review in light of more recent developments in the scholarly literature.Footnote 2 Invoking tradition as authority is usually seen to be a different intellectual approach from appeals to rationality (compare Max Weber’s Reference Weber1922:12 four ideal types of social action: instrumental rational, value rational, affective, and traditional).

A sense of canonicity seems particularly evident in the manner in which the Skåäng inscription has been treated. Where the runic inscription <harja> appears on the 2nd-century Vimose comb (Krause & Jankuhn Reference Krause and Jankuhn1966, inscription 26; Imer Reference Imer2014:325), the Skåäng inscription has long been held to preserve an unexpected variant <harija>. Epigraph-ically, the text on the Vimose comb is quite clear, but it is not often admitted that the older runic Skåäng inscription is problematic and not just because of the unetymological palatal vowel that seems to appear before the glide in the reflex of the Proto-Germanic onomastic theme + harja- ‘army’. The Skåäng stone also preserves a star-like character, a second allograph of the older j-rune, that has often been taken to separate its older runic text into two parts.

Sievers had been a key figure in the Neogrammarian movement, a school that emerged in historical linguistics during the formative period in the study of the older runic texts. Beginning in the 1860s, scholars such as Ludvig Wimmer and especially Sophus Bugge first applied formal linguistic techniques to their studies of the early runic inscriptions. By the 1870s, however, the Neogrammarians had come to see their analytical approach as comparable to those found in the physical sciences (Christy Reference Christy1983). This confidence in their linguistic method has since become especially associated with the assertion by Hermann Osthoff and Karl Brugmann (1878:xiii) of a principle of uniformity: “Aller lautwandel, so weit er mechanisch vor sich geht, vollzieht nach ausnahmslosen gesetzen.”Footnote 3 Matthew Chen (Reference Chen1972) argued that this view was “glib” and “unfounded,” and given demonstrations of the influence of other factors in phonological change, most linguists today accept that the Neogrammarian principle of uniform sound change cannot be accepted uncritically (de Oliviera 1991, Campbell Reference Campbell, Durie and Ross1996). However, the Neogrammarian principle of uniformity is characterized by Bill Labov (Reference Labov1972:100) as “the chief methodological principle of historical linguistics,” and it seems a fair methodological principle in turn to accept that exceptions to the Neogrammarian principle of exceptionless sound change should not be readily accepted in interpretations of the remains of only fragmentarily attested languages.

Theodor von Grienberger (Reference Grienberger1906:110) was the first to overtly excuse the failure of Sievers’ Law to apply properly in the Skåäng inscription, observing that the “correct” spelling <harja> was preserved on the Vimose comb. Regular Sievers’ Law distributions are well attested in runic inscriptions otherwise, but unexpected developments comparable to the Skåäng inscription’s <harija> are allowed in interpretations presented by Krause and Antonsen of several other relatively late older futhark texts. The Neogrammarian principle of exceptionless sound laws seems particularly important in considerations of Sievers’ Law, however. Recently, Andrew Byrd (Reference Byrd, Stephanie, Craig Melchert and Vine2010, Reference Byrd2015:183–207) has summarized the comparative evidence in agreement with Sievers: In Indic and Germanic, “some semblance” of Sievers’ Law is productive, whereas in other Indo-European dialects it is “moribund and has been lexicalized” or is not detectable at all. The Gallehus inscription’s <holtijar> shows Sievers’ Law applying to a term that had a short root in Indo-European (holt- ‘wood’ < + hult- < + kl̥d-; compare Greek κλάδος ‘branch, shoot, twig’), but that after the syllabification of + l̥ had become a long base—evidence that Sievers’ Law remained productive in Germanic. Byrd argues that Sievers’ Law should be seen not as a sound change, but as a postlexical rule still active in early Germanic. As he points out, postlexical rules “tend to be exceptionless” and, in keeping with Don Ringe’s (Reference Ringe2017:133) characterization of Sievers’ Law in Proto-Germanic, should not be expected to brook variation of the type proposed to appear in the early runic evidence.

Rather than accept that violations of Sievers’ Law are attested in older runic texts, an approach more in keeping with linguistic principle is to question whether or not forms such as the unexpected Skåäng sequence have been interpreted correctly. The older runic Skåäng inscription shows signs of being a transitional text, dating to the period when the older runic tradition had begun to show signs of instability and a series of characteristic differences from earlier practice are attested (Barnes Reference Barnes and Düwel1998). These include, most prominently, the development of a new use for the older j-rune in a process that is difficult to explain solely from a phonological perspective. Like the fate of the older j-rune, the interpretation of the older runic Skåäng inscription and other runic finds proposed to feature irregular realizations of Sievers’ Law are problematic and may reflect flawed analysis.

In order to set out the issues more fully, a broader consideration of the historiography regarding the Skåäng runestone is presented in the next section followed by an assessment of how the proposed exceptions to Sievers’ Law have otherwise been explained. All of the apparent exceptions to Sievers’ Law are re-examined to see whether other interpretations are possible—to critically assess the likelihood of each of the interpretations that have been employed to argue for further exceptions to Sievers’ Law. After this critical reappraisal, the appearance of both forms of the older j-rune in the Skåäng inscription are assessed in the third section in terms of the broader development of the runic alphabet during the transitional runic period. The empirical bases of the claimed exceptions to Sievers’ Law are much weaker than is often admitted in the historiography.

2. Background

The Skåäng runestone was first published in 1830 (Sjöberg Reference Sjöberg1822–1830:118, plate 59, figure 191), but it was not until 1867 that the older runic inscription that is preserved in the middle of the Iron Age monument was published by George Stephens (Reference Stephens1866–1901, vol. II:887–888). Stephens’ informant, Hans Hildebrand, had discovered that the runestone preserved two inscriptions, one in younger runes running in a band about the monument, with an earlier inscription preserved in the center of the inscribed face of the stone. Today, the runestone can be seen lying just off the road from Vagnhaärad to Gnesta in Södermanland, Sweden, and its older runic inscription is one of the many texts that at first seemed to fit Sir David M. Wilson’s dictum (in Page Reference Page1999:10) of interpretational overpopulation: For many years it seemed that there were as many interpretations of the older Skåäng inscription as there were interpreters willing to write on it.

The younger runic inscription is inscribed on a decorative ribbon as if to frame the older text and can be translated uncontroversially. Its perhaps 11th-century runic text runs from the lower right in counter-clockwise direction (Brate & Wessén 1924-1936, inscription 32):

(2)

By the 1920s, however, four main proposals had arisen regarding the proper interpretation of the older Skåäng inscription. Wimmer’s (Reference Wimmer1887:166) judgment was that the text preserved two names, Haringa and Leugar, separated by a symbol (accidently) similar to a younger runic <a> and terminated by another symbol that looked somewhat like a 7. Yet Bugge (Reference Bugge1892:19, 22) disagreed, taking Wimmer’s <a>-like sym-bol to be a letterform, reading it as part of the second name, that is, Aleugar. In 1924, Erik Brate (in Brate & Wessén 1924-1936, inscription 32) instead preferred to transcribe the contested star-like form as <j> suggesting that it stood for a North Germanic cognate of Gothic jah ‘and’, while in the same year Otto von Friesen (1924:127) supported von Grienberger’s (Reference Grienberger1906:110) proposal that a name unexpectedly spelled <harija> was recorded on the stone, although von Friesen preferred to take the star-like character as an irregular runic <n>, a genitive marker indicating a patronymic ‘Harija’s (son)’.

There has been no real debate over how to make out the Skåäng characters; the text clearly reads ᚺᚨᚱᛁᛃᚨᚼᛚᛖᚢᚷᚨᛉ7. Yet it was von Friesen’s 1924 study of forms of the older j-rune (previously interpreted as < ͡ng> or an “open” variant of <ŋ>) that convinced subsequent scholars that von Grienberger (Reference Grienberger1906:110) had been right to read the first name in the older Skåäng inscription as <harija> (rather than <hari͡nga>), a phonologically unexpected form given the name harja preserved on the Vimose comb. Von Friesen’s confirmation of von Grienberger’s reading was accepted by Krause (Reference Krause1937, inscription 65) and has since become a standard assumption. Antonsen (Reference Antonsen1975, inscription 73) adopted von Friesen’s interpretation, accepting a genitive reading <harijan> (with <n> a “reversed rune” corrected by the inscriber) where Krause had only accepted von Grienberger’s name <harija>. Krause did not know what to do with the apparent <a> that seemed to separate <harija> from <leugar>.

The final symbol on the Skåäng stone looks to be a punctuation mark, similar to a form known from classical epigraphy that Elvis Wingo (Reference Wingo1972) called a virgula ansata. Krause’s adoption of von Grienberger’s reading, however, is the one that appears in Lisbeth Imer’s (Reference Imer2014:249) catalogue of the older inscriptions. In his recent introduction to Proto-Norse, Schulte (Reference Schulte2018:80) also seems to accept Krause’s interpretation of the inscription as <harijaᚼleugar7>, noting that this reading violates Sievers’ Law, but accepting it as an exception. Sievers’ Law is one of the most widely studied phonological developments in Indo-European and Germanic, and it is universally acknowledged that a palatal vowel should not appear in a form with a short root such as <harja>. Despite the significant growth in the number of older inscriptions now known, however, no new apparent exceptions have come to light since the 1970s except for a dubious case adduced by Syrett.

The apparent violation of Sievers’ Law is the feature that has drawn the most attention to the older runic Skåäng inscription. Ènver Makaev (Reference Makaev1965:85–86) argued that unexpected spellings such as <harija> were merely an orthographic issue, while Springer (Reference Springer1975:176–177) suggested that they reflected the loss of the contrast of -j- and -ij- after North Germanic syncopation and stood (somehow) for phonetic nonsyllabics. Antonsen (Reference Antonsen1975:17) argued that “we must be dealing with a morpho-phonemic phenomenon in which the original phonological rule is still visible, but not productive,” and Schulte (Reference Schulte2018:81) similarly speaks of a “Fossilisierung” of Sievers’ Law variants, pointing to the difference in age of the attestation of <harja> (ca. 160) and <harija> (ca. 375/400–560/570) as a sign of morphological development of the -jan-stems. Krause (Reference Krause1937, inscription 65) merely claimed that runic inscribers treated Sievers’ Law vowels inconsistently: “Die Schreibungen -ja- und -ija- wechseln in den urnordischen Inschriften willkürlich … Ein altes Lautgesetz, wie man früher annahm, liegt diesen Schreibungen nicht zugrunde.”Footnote 4 He specifically pointed to the spelling <stainawarijar> on the stone from Rö, presuming that the onomastic element <-warijar> (also attested on the fibula from Nøvling and one of the stones from Tørvika) represented an expected +-warjaz ‘defense’.

The main argument for accepting that <-warijar> represents +-warjaz is the name <ladawarijar> attested on the Tørvika A stone, which Antonsen (Reference Antonsen1975, inscription 32) agreed should be connected to Old High German lantweri ‘levée en masse’, literally ‘land defense’. Syrett (Reference Syrett1994:186) suggested that the unexpected vocalizations represented epenthetic vowels, but three geographically and chronologically diverse attestations of the spelling <-warijar> can scarcely be explained as due to orthographic errors or epenthesis. Schulte (Reference Schulte2018:79) instead follows Springer (Reference Springer1975:173), who argued that the unexpected vocalism arose from analogy with longer forms such as Gothic ragineis ‘advisor, counselor’ (not + raginjis). Yet similar spellings do not occur in early runic forms such as <swabaharjar> on the Rö stone (which also features <stainawarijar>), so such an explanation seems quite ad hoc (cf. Springer’s assertion that <swabaharjar> may have been subject to analogy with + harjaz but that <stainawarijar> was not equally influenced correspondingly by + warjaz). As Eric Harding (Reference Harding1937:52–53) and Alfred Bammesberger (Reference Bammesberger2008) have argued, however, <-warijar> can be interpreted more regularly as featuring a root cognate to Old Norse vár ‘oath’, Old English wǣr ‘true’, and Old High German wār ‘true’ (< + wēraz; compare Latin vērus ‘true’) and hence to accord with Sievers’ Law (compare Förstemann Reference Förstemann1900:1531–1532). It was the interpretation of <-warijar> accepted by Krause and Antonsen that seems to have been irregular, not the runic spellings.

Another widely accepted example of a violation of Sievers’ Law appears on the Nord-Huglo stone, now conserved in the University Museum of Bergen. Originally proposed by Magnus Olsen (Reference Olsen1911:10) to feature a name Guðinga, von Friesen (1924:123–124) corrected this interpretation, taking Olsen’s reading <͡ng> as <j>, with the erstwhile name becoming an irregularly spelled cognate of Gothic gudja ‘priest’. Old Norse preserves a different construction, goði, for ‘priest’ that seems to continue an earlier + guda(n), much as the etymologically related feminine gyðja ‘priestess’ (also ‘goddess’, with gyðja < + gudjō(n); compare Old English gyden ‘goddess’ < + gudinjō(n)) is constructed differently in North than in West Germanic. However, <gudija> could also be taken to represent Gu(n)þija with a <d> for expected +<þ>, much as occurs in the phonetic orthography <hadulaikaz> (for Haþulaikaz) that is preserved on the Kjølevik memorial (Krause & Jankuhn Reference Krause and Jankuhn1966, inscription 75, Imer Reference Imer2014:147). There is some evidence for a Verner’s Law variant + gundi- attested onomastically (Schaffner Reference Schaffner2001:458), but the Noleby inscription (Krause & Jankuhn Reference Krause and Jankuhn1966, inscription 67) similarly preserves a form <raginakudo> that seems to be reflected in Old Norse as reginkunnr (< + raginakunþaz), and hypocoristic forms of names feature-ing the onomastic theme + gunþi-, + gunþijō- ‘fight’ are attested in 30 or so younger runestone texts as Gunni (Peterson Reference Peterson2007:92).

The main drawback with this explanation is that the form <ungandir>, unexpectedly for a runic inscription, indicates a nasal before a homorganic obstruent in -gand-. However, the onomastic theme + gunþi-, + gunþijō- ‘fight’ is quite common in Germanic (Förstemann 1901:693–713) and taking the Nord-Huglo form <gudija> as a masculine name would be more expected syntactically as it is irregular for functional titles to precede given names in North Germanic (for example, Snorri goði Þorgrímsson and Arnkell goði Þórólfsson; see Mees Reference Mees2018). As Olsen (Reference Olsen1911:16–19) first suggested, <ungandir> looks to be an adjectival cognomen formed from a privative + Ungandijaz (compare Old Norse gandr ‘magic’), but despite the literal meaning of <ungandir>, its formal analysis only seems to underline the impression that <gudija> is an anthroponym (presumably of the Chunradus qui et Chuono ‘Chunrad also known as Chuono’ type). Krause’s association of <ungandir> with the Danish royal name Ongendus has not been generally accepted, with a (linguistic) connection of Ongendus to Old English Ongenþeow normally considered more likely (Frank Reference Frank, Beck, Geuenich and Steuer2002). Gandr appears to have been a kind of weather magic (Heide Reference Heide2006), and it is more exciting to find a pagan priest mentioned on a runic monument than just a name. However, Krause was renowned for favoring magico-religious interpretations over mundane explanations, and from a linguistic perspective it is preferable not to accept an interpretation that suggests that the inscriber of the Nord-Huglo monument did not know how to write in a manner that accorded with Sievers’ Law or the usual syntax that applied in old Germanic naming. Applying Bammesberger’s Neogrammarian approach to the few instances where Krause thought that Sievers’ Law was violated by early runic inscribers would mean that interpreting <gudija> as the name Gu(n)þija should be preferred.

A further example of a form claimed by Krause (and Antonsen) to feature an irregular realization of Sievers’ Law is the sequence <þrawijan> attested on the Kalleby stone. Krause followed von Friesen (1924:129–133) in connecting the Kalleby text <þrawijan> with the Old Norse verb þreyja ‘to feel for, to yearn after, to wait patiently’ (< + þraujan-). Yet Koivulehto (Reference Koivulehto1981:347) connects Finnish raavas ‘robust, strong’ and rahvas ‘commoners, people’ with Old High German drouwan, -en ‘to grow (up)’ as if they continue + þrawwaz, and Lloyd et al. (Reference Lloyd, Rosemarie and Springer1998:795) reconstruct drouwan as a continuation of Proto-Germanic + þraww-. Old High German drouwan and the Finnish forms suggest that <þrawijan> is best understood as a genitive patronymic Þraw(w)ijan ‘Þrawwija’s (son)’.

Finally, Syrett’s claim that the Illerup form <niþijo>, inscribed on a silver shield grip found in the votive bog in 1983, could represent another exception to Sievers’ Law depends on the vowel of the root <niþ-> being short. As Schulte (Reference Schulte2018:92) recognizes, however, Old Norse niðr ‘relative’ and Gothic niþjis ‘kinsman’ are not the only possible cognates of <niþijo>. The Illerup form can also be compared to Old Norse níð ‘libel, defamation’, Old English nīþ ‘envy’, Gothic neiþ ‘hate, malice’, and the verbal root + ninþ- attested in Old High German ginindan ‘to dare’. If anything, the ending <-ijo> might better be taken as evidence that a connection with Old Norse niðr ‘relative’ and Gothic niþjis ‘kinsman’ is to be eschewed, not as evidence of another possible exception to Sievers’ Law.

3. North Germanic Glide Loss and the Skåäng Inscription

Adopting a similar Neogrammarian approach to interpreting the older runic Skåäng inscription requires another kind of analysis. The simplest manner in which to explain a linguistically regular early North Germanic spelling <harija> is to interpret it as an agentive form of Old Norse hār, Old English hǣr, Old Saxon hēr, Old High German hār ‘hair’ (< + hēra-). However, as Springer (Reference Springer1975:176) has argued, this approach seems to be vitiated by how common names formed with the element + harja- are in Germanic. Yet the Skåäng stone is remarkable not just for preserving both a younger and older runic inscription; the older text is also notable for its featuring both the s-like (ᛃ) and star (ᚼ) forms of the older <j>—or <a>, if the runestone is recent enough to postdate North Germanic glide loss. Imer (Reference Imer2014:249) dates the older Skåäng inscription to ca. 375/400–560/570 (that is, the Migration Period) on account of the form of the <e> and the rune taken by Krause as a <j>, so it may well date to the period after North Germanic glide loss.

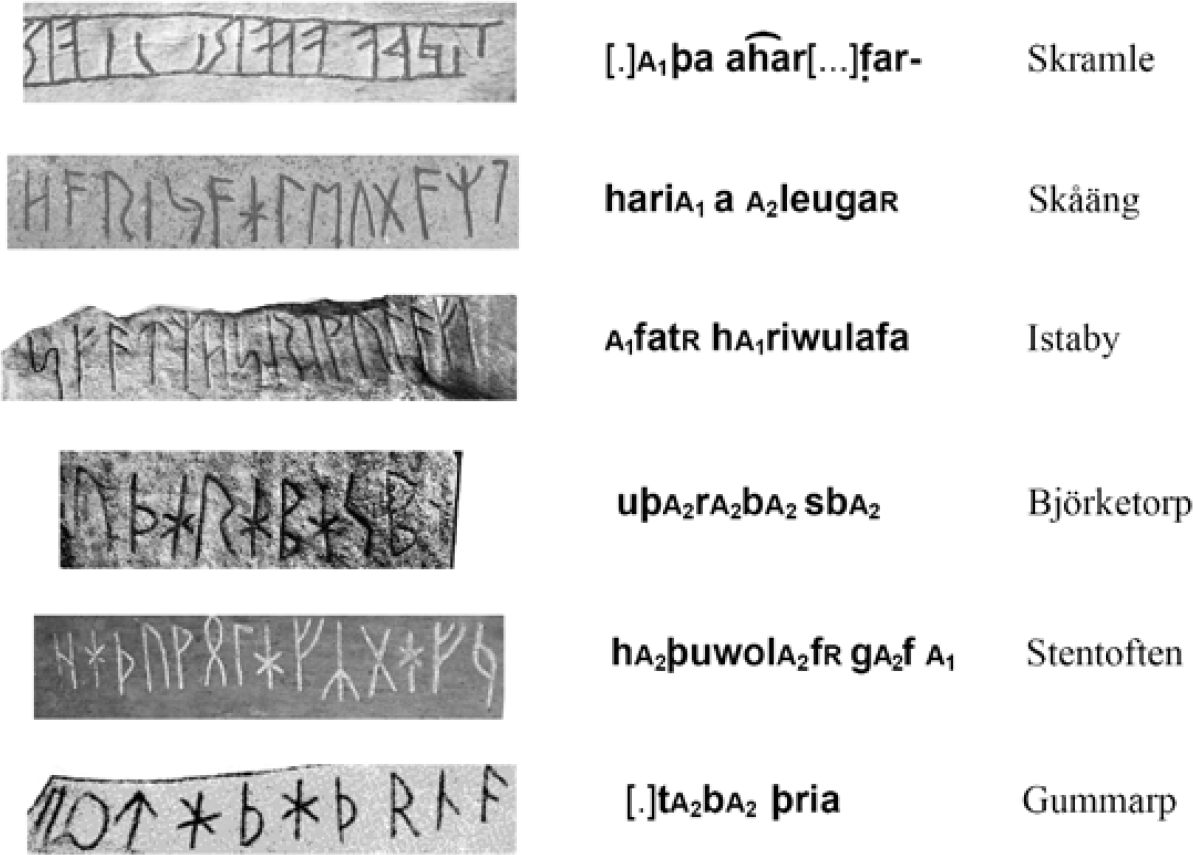

The s-like allograph (ᛃ) is a development of the older j-rune. The star-like allograph of the j-rune (ᚼ) was explained by Derolez (Reference Derolez1987) to have arisen from a ligature of <g> (ᚷ) and <i> (ᛁ) after the palatalization of /g/ (to [j]) before /i/ occurred in the coastal dialects of West Germanic and early Danish; it later came to represent /h/ in the younger futhark after the s-like allograph ᛃ came to represent oral ā̆. However, it is generally thought that the loss of the glide in the rune name + jāra led both allographs of the j-rune to initially become a-runes, a development traditionally seen to be clearest in the inscriptions that form the Blekinge group (Krause & Jankuhn Reference Krause and Jankuhn1966, nos. 95–98). Hence the transitional Istaby stone (tentatively dated to ca. 520/530–560/570 by Imer Reference Imer2014:138) features an s-like form of <a> (ᛃ) and the Björketorp memorial (from ca. 520/530–700 according to Imer Reference Imer2014:17) features use of the star-like <a> (ᚼ), both to represent vowels rather than glides. The star-like allograph of the older j-rune is also employed in the name <hḷahahaukr> (< + Hlaha-habukaz ‘Laughing-hawk’) on the Vallentuna gaming piece, dated by Carbon 14 analysis to ca. 615/655 +/- 85 years (Gustavson Reference Gustavson and Sjosvard1989, Imer Reference Imer2014:313).

The only exception to this development among the Blekinge group has long been supposed to be the Stentoften monument (dated to ca. 520/530–700 by Imer Reference Imer2014:264), where the s-like allograph of the older j-rune was transliterated by Krause as <j>, while the star-like allograph is generally accepted to be an <a>. This phonologically anachronistic distinction is faithfully repeated by Schulte (Reference Schulte2018:99), but it is not required if the s-like allograph is to be taken as a runic ideograph. The idea that ideographic uses of runes attested in medieval manuscripts can be projected back onto the older texts is controversial (Mees Reference Mees2011) as is the notion of “archaicizing” spellings (Antonsen Reference Antonsen2002:296-314). However, it makes no difference to the sacral-kingship interpretation of the Stentoften inscription whether or not the ᛃ is thought to represent a phonologically archaic reference to the older rune name + jāra or its j-less reflection + āra—the assumed phonological archaism is both unmotivated and unnecessary.

While Brate represented the Skåäng inscription as <hari͡nga j leugar>, it is clear that its letterforms could equally be transliterated either as <harijajleugar> or <hariaaaleugar>—or if the allographs ᛃ (<a1>) and ᚼ (<a2>) are distinguished by the age of their first attestation, perhaps rather <haria1aa2leugar>. Following Krause’s anachronistic reading of the s-like allograph on the Stentoften inscription, a trans-literation <harijaa2leugar> might be allowed, but from a Neo-grammarian perspective, the choice should presumably depend on whether or not the inscription pre- or postdates glide loss and the operation of Sievers’ Law. Bugge took the second name to be <a2leugar>, which could represent a similar construction to the form <alaif̣ụ> that has often been thought to appear on the presumably 6th-century By memorial, and Krause took <alaif̣ụ> to be A(n)laiƀu < + Anulaibu, the transitional runic equivalent of the younger Skåäng inscription’s Ólo˛f (Krause & Jankuhn Reference Krause and Jankuhn1966, inscription 71; Imer Reference Imer2014:28). Under this reading, the star allograph <a2 > would represent a nasalized vowel, the reverse of what becomes the standard distinction between <a2> and <a> in later transitional inscriptions. As Syrett (Reference Syrett1994:113) points out, however, syncopation of the stem vowel in putative + Anu- is not paralleled elsewhere in the By inscription, so a form prefixed by an ‘on, upon’ might be preferred in <a2leugar> (compare Gothic liuga ‘marriage’ and Old High German urliugi ‘war’).

If the second name is to be read <a2leugar>, the first seems most regularly to be taken as <haria1 >, with the s-like allograph <a1> repre-senting a different distinction. On the Istaby stone, <a1 > represents /a/, while <a> indicates an epenthetic vowel, presumably /ə/, and the accusative singular ending < +-an. In <haria1 >, a distinction seems to be made between stressed /a/ and the unstressed n-stem nominative singular ending that is argued by Nedoma (Reference Nedoma2005) to be -æ < +-ēn in early runic. Ringe (Reference Ringe2017:307, note 29) rejects Nedoma’s interpretation, however, maintaining (with Lid Reference Lid1952 and Syrett Reference Syrett1994:134–152) that the Old Norse n-stem nominative singular marker -i is analogical (from the heavy jan-stems) rather than inherited. Given the use of <a> to represent an epenthetic vowel on the Istaby memorial and the appearance of the syncopated spelling <ha2ri-> on the Stentoften stone, there is also the possibility that <a1 > represented a reduced vowel /ə/ in <haria1 >. Brate explained the unexpected star allograph <a2 > as a reflex of Gothic jah ‘and’, but after glide loss the inherited conjugation (compare Old English ge, Old Saxon ja, and Old High German ja ‘and’ < Indo-European + i̯o-k u̯ e) was presumably reflected in North Germanic as a before it was lost altogether and replaced by auk, ok ‘also, and’ (Willson Reference Willson2017:528–529). The older Skåäng inscription might reasonably be taken to read <haria1 a a2leugar>, Harjə a A(n)leugar (compare the younger inscription’s <skanmals auk×olauf>).

This analysis of the older Skåäng inscription seems to be supported by the difficult text on the Skramle stone, discovered in 1993 during the excavation of a high medieval site in Värmland. The inscription is damaged, but with the aid of laser scanning it is read by Gustavson & Swantesson (Reference Gustavson and Swantesson2011:311–316) as <[.]jþa a͡har[…]f̣arkano>. The sequence /jþa/ seems phonotactically unlikely in an early North Germanic text, so the s-like rune on the Skramle stone seems better read as <a1 >. Although the initial sequence appears too fragmentary for it to be restored, /aþa/ and /əþa/ are the expected phonotactic sequences rather than /jþa/ in early North Germanic. The Skramle inscription appears to preserve the s-like old j-rune (<a1 >), being employed for a vowel in what Gustavson and Swantesson judge by the shape of the letterforms to be a 7th-century inscription that also evidently features the older a-rune <a> representing both oral and nasal ā̆. The Skramle and older Skåäng inscriptions seem to reflect an early stage in the transition to the younger runic alphabet.

Barnes (Reference Barnes2012:54–59) describes the different ways in which the transformations to the runic alphabet that occurred during the transitional period have been explained. The dominant explanation (after Liestøl Reference Liestøl1981a,b) ascribes the changes to reforms of the orthographic system after phonological developments (such as glide loss) had occurred in the associated runic letter names. Schulte (Reference Schulte2011) champions the influence of broader phonological (and systemic) developments, but it is not clear whether or not phonologically predicated explanations alone can account for the variation in the use of <a>, <a1 >, and <a2 > attested in the transitional inscriptions. As Lass (Reference Lass and Lieb1992:265) describes it, sound change usually occurs through “cumulative, directionally weighted variation”, but the different use of the old j-rune attested in the transitional inscriptions often appears to represent another kind of variation. The names of the old j-rune could have been represented synchronically for a time as both + jāra and + āra (perhaps in different sociolects), but the use of different allographs of the same grapheme in the contemporary and geographically proximate inscriptions of the Blekinge group does not appear to be phonologically motivated. Rather than accepting an irregularity owing to the presence of a linguistically archaic “residual form” (in the sense of Chen Reference Chen1972), inscriptions such as the Skramle text suggest a period of experimentation after the loss of initial j created a second a-rune (table 1). Using the new a-rune to distinguish oral from nasal vowels in a manner suggested by the later rune names óss ‘god’ (< + ansuz) and ár ‘year’ (< + jāra) seems to be a practice that was only adopted at a relatively late stage of the transitional period.

Table 1. The development of the a-runes after glide loss.

Two main allographs of the old j-rune were available; they appear to have been used at first in different manners by different inscribers until the regularized distribution between nasal and oral back vowels characteristic of younger runic texts became established. On the Istaby stone, <a1> varies with <a>, while the Björketorp memorial exclusively uses <A 2>, and the Stentoften inscription employs all three of the relevant letterforms (with Schulte taking <a> as representing a(n) and <a1 > as an ideograph on the Stentoften stone). The Skramle and older Skåäng inscriptions seem to indicate that the inherited <a> was first employed to represent oral ā̆, and that after glide loss, <a1> and <a2> were initially used only to indicate what were perceived to be variations of ā̆ before the usage distinguishing nasal and oral sounds known so well from younger inscriptions became established. The Istaby and Stentoften inscriptions subsequently appear to show a stage where the allographs of <a> had displaced <a> from its earlier role, with the new system fully established on the lost Gummarp stone (albeit with the star allograph <a2> employed where younger runic inscriptions come to exclusively employ <a1>; see figure 1.)

Figure 1. The use of the a-runes in the transitional inscriptions.

Instead of a gradual, phonologically driven process, the loss of the initial glide from the rune name + āra seems to have led at first to a period of relatively ad hoc employment of the two main allographic forms of the older j-rune. These relatively ad hoc usages could include the repre-sentation of epenthetic vowels until a new distribution became established, based more faithfully on the articulation of the two rune names, one of which preserved a nasalized vowel. Triggered by glide-loss, the subsequent developments reflected a readjustment of the runic spelling system, with a period of experimentation preceding the establishment of uniformity, rather than a cumulative analogical process.

4. Conclusion

Runology was transformed in the 1860s by a generation of scholars who for the first time assessed the older runic texts in light of the develop-ment of comparative philology. As figures such as Sievers further refined the comparative method, the sound laws established by the Neo-grammarians were used to cumulatively improve linguistic inter-pretations of older runic texts. Since the 1960s, however, investigations of the older inscriptions have often been captured by a sense of canonicity, as interpretations proffered in Krause’s corpus have come to have an undue weight on linguistic interpretations derived secondarily from his scholarship. This practice is particularly evident in the interpretation of the form that Krause read as <harija> on the Skåäng stone (that may equally be taken as <haria a>), to the point where it seems to have licensed runologists to produce a set of interpretations that do not accord with Sievers’ Law. Allowing exceptions to sound laws has become one of the more problematic practices to have developed since the late 19th century when methodologies established by figures such as Sievers were introduced to runic studies. Changes that reflect phono-logical developments, such as the reemployment of the older j-rune to represent a vowel, need not be bound by the same cumulative and regularizing dynamic. However, bending the Neogrammarian principle of linguistic uniformity to serve an overriding sense of historiographical tradition does not seem to be the most rational manner in which to further the progress of the discipline. If any bending is to occur, it is that the traditional interpretations of early runic texts preserved in the works of scholars such as Krause need to give way to well-established analytical principles such as phonological uniformity.

Yet the early runic texts remain an essential resource for the analysis of Germanic language history. They often preserve phonological and morphological evidence that is not preserved in Gothic, and the number of texts uncovered by archaeologists is constantly expanding—in a manner that contrasts with the testimony recorded in medieval manuscripts. Newly uncovered runic inscriptions allow linguists to revise and improve earlier theories of the development of the Germanic languages. The proper analysis of runic inscriptions remains of crucial importance for historical linguistics because the older epigraphic texts preserve key—and often unexpected—evidence for early Germanic language history. The exceptions to Sievers’ Law long allowed in the runological historiography are just one of several linguistic oddities accepted even in the most recent surveys of the early runic inscriptions. The uncritical sense of canonicity warned of by Peterson remains one of the main barriers to developing a more rigorous understanding of the early development of Germanic. As more and more epigraphic evidence is uncovered, however, longstanding shibboleths are increasingly revealed to be founded on outmoded assumptions, and a clearer picture is revealed of early Germanic grammar.