1. The Adnominal Genitive in German

The adnominal genitive is one of a number of syntactic devices to express a possessive relationship between two noun phrases in German. It can be used either in prenominal or in postnominal position:

(1)

In prenominal position the genitival noun phrase occupies the position of the determiner. The postnominal variant is considered the unmarked form in modern German, whereas the prenominal form is stylistically marked and used predominantly for proper nouns.

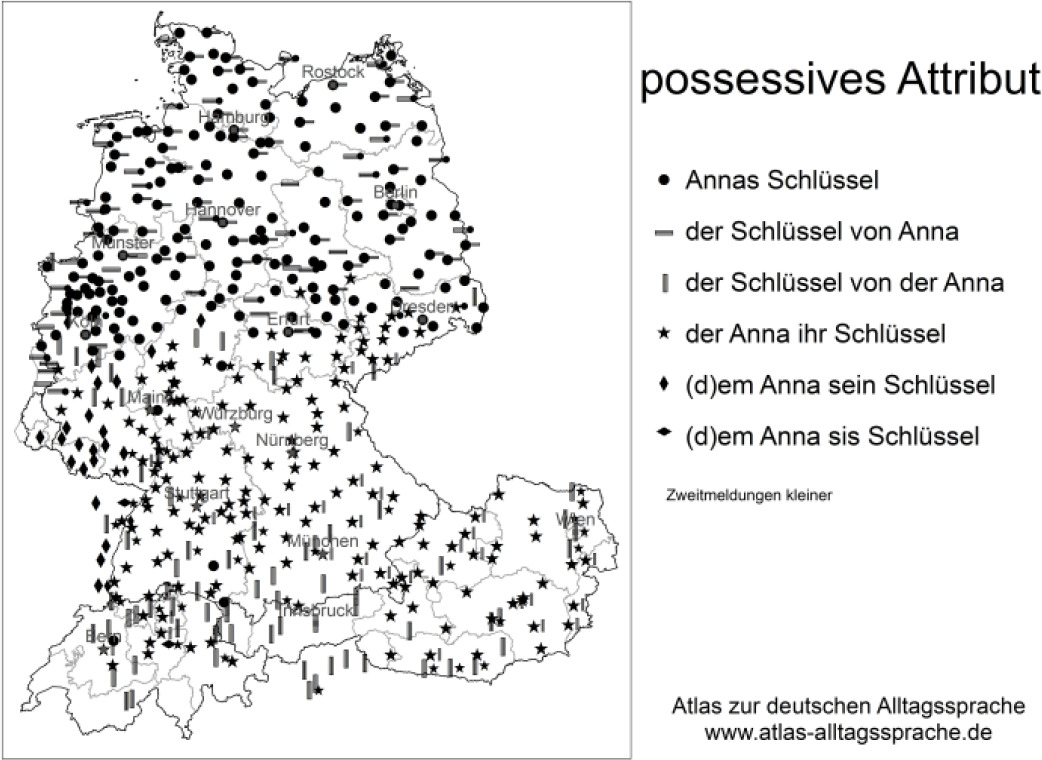

The adnominal genitive today is found predominantly in formal standard German; in informal spoken language, only certain forms of the adnominal genitive are used in some regions: “Except for a few set expressions, the genitive is now restricted in the standard language to rather more formal registers; in German dialects it survives only in a few idioms” (Barbour & Stevenson Reference Barbour and Stevenson1990:84). According to Fleischer & Schallert (Reference Fleischer and Schallert2011:94), the adnominal genitive has been completely replaced by other constructions in the German dialects. It is, however, used in varieties of colloquial German that are based on written German (see Dal Reference Dal2014:25–26). Hence, while the adnominal genitive is widely used in formal standard German and obsolete in German dialects, there is some variation across the diaglossic standard/dialect continuum (see Auer 2005 for different standard/dialect constellations in Europe). While the usage patterns of the adnominal genitive in different registers and regions is not documented in great detail, limited insights into the distribution of some of its forms can be gleaned from individual studies. For instance, the Atlas zur deutschen Alltagssprache (AdA; Atlas of colloquial German), which documents everyday usage of spoken German elicited through online surveys, indicates that the prenominal genitive of personal names is used in northern Germany (see figure 1), but not in other parts of the German-speaking area.Footnote 1 Information about types of genitival constructions other than Annas Schlüssel ‘Anna’s key’ and the six variants to render this in colloquial German, however, is not documented in the AdA.Footnote 2

Figure 1. Forms of the possessive attribute in everyday German.Footnote 3

Dal’s (Reference Dal2014:25–26) observation that only colloquial German “auf der Schriftsprache fußend” [based on written German] uses the adnominal genitive appears to hold true also in a geographical sense: The area where the genitive is used according to figure 1 is largely congruent with the traditional Low German area (although extending somewhat further south). This is the area where today’s colloquial High German variety has ultimately derived from a reoralized variety of written High German that was later dubbed Nieder-Hochdeutsch ‘Low High German’ (see Wells Reference Wells1985:304, 469) and became the model for standard German pronunciation (see Schmid Reference Schmid2017:112). It seems plausible that a syntactic feature such as the adnominal genitive might also have found its way into northern spoken language following the model of written High German. Alternatively, the presence of the adnominal genitive in northern German could be a consequence of a Low German substrate effect, assuming that Low German had retained the adnominal genitive longer than High German dialects.Footnote 4 Generally, the genitive is only found sporadically in recent spoken Low German dialects (see Kasper Reference Kasper2017:303); again, it is unclear whether these instances are remnants of the original (West-) Germanic genitive or a result of standard German influence (see Kasper Reference Kasper2017:306 for Westphalian in Hesse).

Since Behaghel Reference Behaghel1923–1932, I:489–480, and as recently as Fleischer & Schallert Reference Fleischer and Schallert2011:84–87, several statements have been made in the literature regarding those areas where remnants of the genitive can be found, but overall only fossilized forms of the genitive have survived until the most recent times. One exception is the presence of the prenominal genitive of personal names in northern Germany, which, as discussed above, might well be a secondary development resulting from standard German influence on the northern spoken varieties rather than a continuation of the original (West-)Germanic genitive, if it is counted as a true genitive at all (see figure 2). Since the adnominal genitive is largely absent from modern spoken German but attested in historical written sources of (West-)Germanic languages in general, it must have been lost in spoken language at some point. Behaghel (Reference Behaghel1923–1932, IV:189) notes that with the beginning of the early modern period, the genitive as a case started to disappear from spoken German and dates its loss to the 15th century (Behaghel Reference Behaghel1923–1932, I:479–483) on grounds of examples “der Unsicherheit seines Gebrauchs” [of the insecurity of its usage] as well as certain developments in personal names. A more reliable dating of genitive loss that goes beyond such indirect indicators is almost impossible because it is not reflected directly in written sources. Despite its age and conjectural nature, Behaghel’s dating of the loss of the genitive has been neither refined nor disproved since then and is therefore to be taken as the current state of research.

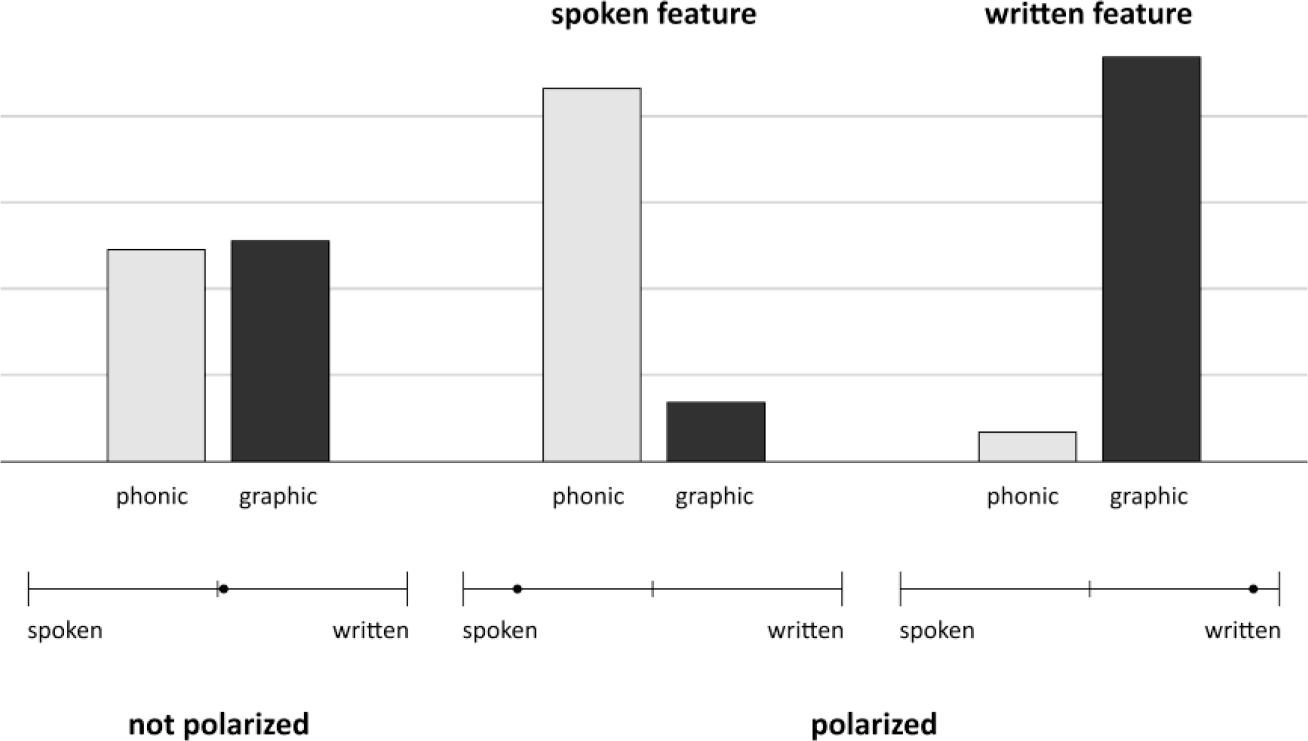

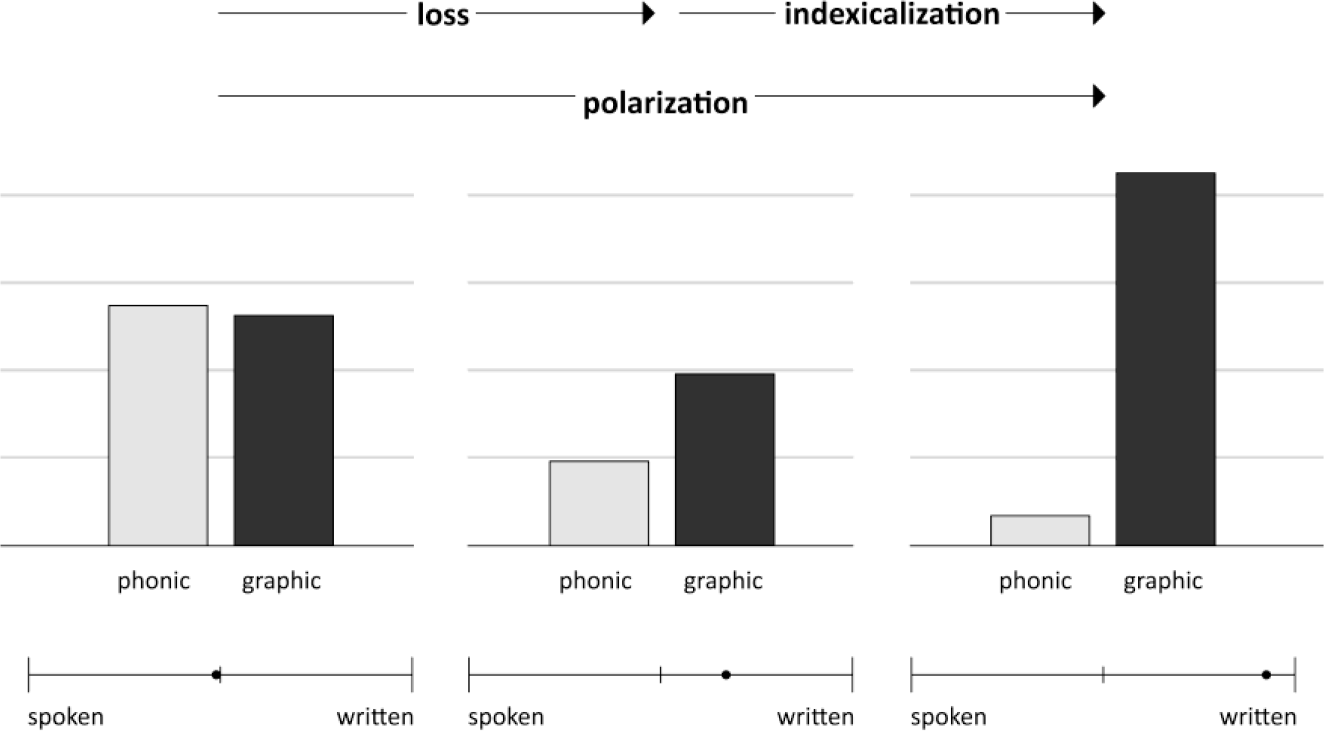

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of nonpolarized versus polarized and spoken versus written features.

While the adnominal genitive has largely disappeared in spoken German, it is very much alive in written standard German. Indeed, it has been characterized as a marker of standard language: “The genitive case is common only in formal standard German, and its presence in a sentence can mark that sentence out as formal and standard” (Barbour & Stevenson Reference Barbour and Stevenson1990:161). As Weiß (Reference Weiß2004:663) points out, “there is a clear motive behind its use by German writers.” This differential development in spoken and written German is difficult to analyze historically because of the lack of any spoken sources (see Fleischer & Schallert Reference Fleischer and Schallert2011:27), even though conceptually oral sources have the potential to yield some indirect insights (see Auer et al. Reference Auer, Peersman, Pickl, Rutten and Vosters2015:7).

This discrepancy between speech and writing, however, is not always reflected explicitly in accounts of the overall development of the adnominal genitive in German, which can lead to seemingly contradictory portrayals of events. Fleischer & Schallert (Reference Fleischer and Schallert2011:99) state that despite the adnominal genitive’s stability in standard German, the genitive “insgesamt” [on the whole] has been disappearing continuously throughout the history of German, and Dal (Reference Dal2014:26) declares that the frequency of the adnominal genitive plummeted in New High German.Footnote 5 Conversely, Reichmann (Reference Reichmann, Berthele, Christen, Germann and Hove2003:47) asserts an “Ausbau” [expansion] of the adnominal genitive from the 16th century onward (see also von Polenz 2013:262). In New High German, according to Ágel (Reference Ágel, Besch, Betten, Reichmann and Sonderegger2000:1889), the usage of the adnominal genitive in written New High German increased rather than decreased. Admoni (Reference Admoni1987), Scott (Reference Scott2014), and Niehaus (Reference Niehaus2016) find an increase in the use of the adnominal genitive in New High German data (literary prose and newspapers) peaking in the 19th century (see Niehaus Reference Niehaus2016:192). This points to a development in written language that is almost opposite to that in spoken language. Scott (Reference Scott2014:311–326) also draws a more nuanced general picture in which the adnominal genitive was on the decline until the 15th century, after which codification and prescription halted and even reversed its disappearance.Footnote 6 This would explain both its persistence in written language and its status as a feature of formal standard language. However, this reversal appears to have started before the advent of codification; prescription, therefore, cannot have been the only reason for the preservation of the genitive (see Scott Reference Scott2014:315–316; see section 4 for a discussion of this problem).

Both the disappearance from spoken German and the persistence or expansion in written German are nontrivial facts that need to be accounted for. According to Fleischer & Schallert (Reference Fleischer and Schallert2011:100), standard German is atypical in having retained the genitive, which is as much in need of explanation as the loss of the genitive in dialects. While there has been research into the question of genitive loss (Behaghel 1923:479–480, van der Elst 1984, Donhauser Reference Donhauser1998), even though no conclusive explanation has been reached (see Fleischer & Schallert Reference Fleischer and Schallert2011:99), the question of genitive maintenance has only been tackled recently (Scott Reference Scott2014). Apart from Admoni Reference Admoni1987, Scott Reference Scott2014, and Niehaus Reference Niehaus2016, studies of the genitive in German have typically focused on word order rather than frequency of usage (for instance, Carr Reference Carr1933, Ebert Reference Ebert1988, Demske Reference Demske2001, Solling Reference Solling2011, Pickl 2019b; see note 4 for Low German). Tükör (Reference Tükör2008:87) reports absolute numbers from a corpus of Early New High German charters from Lower Austria, but they are difficult to interpret because the text sizes are not stated. A consistent investigation of the development of genitive usage in written sources over time, with a particular focus on the time of its loss in spoken language and the centuries leading up to and following it, is therefore called for.

The structure of this article is as follows: In section 2, I discuss the theoretical approach, introducing the core concept of polarization, before explaining the choice of genre for the study (section 2.2), and describing its design and structure (section 2.3). The analysis of the data and its results are presented in section 3. Section 4 presents an attempt at an interpretation of the findings and their implications. In section 5, the conclusion, a summary of the outcome of this study is given as well as a brief outlook.

2. Approach and Data

2.1. Written and Spoken Language

Because the distinction between written and spoken language is crucial for the purposes of this study, I briefly discuss these two concepts and how they are used in this article. Ever since Koch & Oesterreicher Reference Koch and Oesterreicher1985, it has been clear that a distinction has to be made between phonic and graphic medium on the one hand, and spoken and written styles (that is, diaphasic varieties) on the other.Footnote 7 While the two styles are strongly associated with the respective medium, both can be realized in either of them. Written and spoken varieties are primarily characterized by certain linguistic features that can be traced back to the prototypical conditions of production and reception in the respective medium, and, secondarily, by features that have historically become associated with speech or writing. One can thus distinguish between primary (or universal) written/spoken features and secondary (or historically contingent) written/spoken features (see Hennig Reference Hennig2009:36–37, Koch & Oesterreicher 2012:454). The written and spoken styles are prototypically associated with the graphic and phonic medium, respectively. However, in contrast to “graphic” and “phonic”, “written” and “spoken” do not form a binary opposition; rather they are situated along a continuum that goes from, following Koch & Oesterreicher’s 2012 terminology, “language of immediacy” (the spoken variety) at one end to “language of distance” (the written variety) at the other. The transition between these two styles is gradual (much like the transition between varieties in geographical space, see Pickl 2016), with the two ends of the continuum representing the most clear-cut cases. Speakers/writers can shift between them for stylistic effect and produce mixed utterances or texts that exhibit features of both styles. At any point along the continuum, each style can be represented in either graphic or phonic medium and display varying combinations of written and spoken features. In other words, both media are permeable for the features of either style. This entails that some, especially secondary, features associated with the spoken style can be found in the graphic medium and vice versa.

I use the term polarization to describe a stark difference between language usage in different contexts (in this case, in speech and writing) as well as the process leading to it.Footnote 8 One can further distinguish between micro-polarization (figure 2) and macro-polarization (figure 3). The former concerns individual features that show a marked preference for one of two contexts (in this case, the two media). The latter describes a situation or development where two varieties are associated with two different contexts because a large number of features has become micro-polarized between these contexts.Footnote 9 In both cases, while the association of polarized features or varieties with the respective media can be very strong, they are not restricted to that medium but occur in either medium and be used for stylistic effect. In this sense, the adnominal genitive is a feature that is (micro-)polarized between speech and writing, while the varietal spectrum of modern German is (macro-) polarized because such a large number of features are polarized that they form sets of co-occurring variants in both media, and spoken and written varieties or styles can be distinguished.

Figure 3. Schematic diagram of nonpolarized versus polarized variation.

In figure 2, the bars represent the frequency of usage of (non-)polarized features in the phonic and graphic media. The dots in both figures stand for individual linguistic features and indicate their degree of polarization between spoken and written language. In polarized variation, spoken and written styles or varieties can be distinguished.

2.2. A Corpus of Sermons

Sermons have been chosen as the empirical basis for this study because they appear particularly well suited for a diachronic analysis of genitive usage. While they are by no means representative of the entirety of the German language of any particular time, they have certain advantages that set them apart from other sources and allow for an effective analysis while keeping the corpus size manageable.

First, sermons in German are attested from very early on (9th century) and are among the earliest sources of German prose. They have a relatively broad and constant history of transmission—with a transmission gap from the mid-9th to the mid-11th century, which affects virtually all text types—with no major changes as a genre, even though changes in style, transmission type (as in draft versus recorded speech) etc. could occur.Footnote 10 This makes sermons suitable for the diachronic investigation of long-term developments. Most other genres are not long-lived enough to reflect linguistic change over such a long time.Footnote 11

Second, historical sermons are written texts with a particular relation to oral communication. The characteristic communicative setting of sermons is that of an oral address, which written sermons emulate in three ways:

(i) by projecting the use of linguistic devices of an orally transmitted sermon in a draft or manuscript intended for recital (making such examples “speech-purposed”, in the terminology of Culpeper & Kytö Reference Culpeper and Kytö2010:17–18);

(ii) by recording and thus reproducing linguistic features of an orally rendered sermon (which makes such examples “speech-based”); or

(iii) by imitating characteristics of oral sermons in texts that are produced for being read rather than listened to and are not intended for—nor based on—an oral performance in its typical setting (so-called Lesepredigten ‘reading sermons’, which are merely “speech-like”).

According to Kohnen (2010:539), the exact relationship between a written sermon and its oral rendering (and whether it was performed at all) is often unclear:

While we may assume that most sermons were actually preached or intended to be preached at some occasion, we do not know whether the texts that have come down to us reflect the version performed in front of a congregation or whether they were edited later to form a more elaborate and literate piece. Thus, sermons are typically situated between orality and literacy.

Irrespective of which of the three possibilities outlined above applies in a particular case, the text in question is likely to be characterized by both spoken and written features. Mertens (Reference Mertens1992:41) lists a number of linguistic characteristics that give medieval sermons the semblance of an oral speech, and Wetzel & Flückiger (2010:16) declare that oral markers are a constitutive characteristic of the genre—even in the case of reading sermons.Footnote 12

Historical sermons as sources for linguistic study can be character-ized as texts in the graphic medium shaped by conditions that lead to both written and oral features. On the one hand, they are susceptible to factors typical for the written pole such as extensive planning and the form of a monologue (see Biber & Conrad Reference Biber and Conrad2009:144, Koch & Oesterreicher 2012:450) and their propensity for what Kohnen (2010:528) refers to as “elaborate exposition.” On the other hand, sermons reproduce or imitate face-to-face communication (real or imagined) and often show emotional involvement (see Koch & Oesterreicher 2012:450). The language of sermons is therefore neither typically spoken nor typically oral; rather, sermons exhibit a mix of features of spoken and written styles, which is subject to many different factors and may thus change over time.

2.3. Corpus Design and Structure

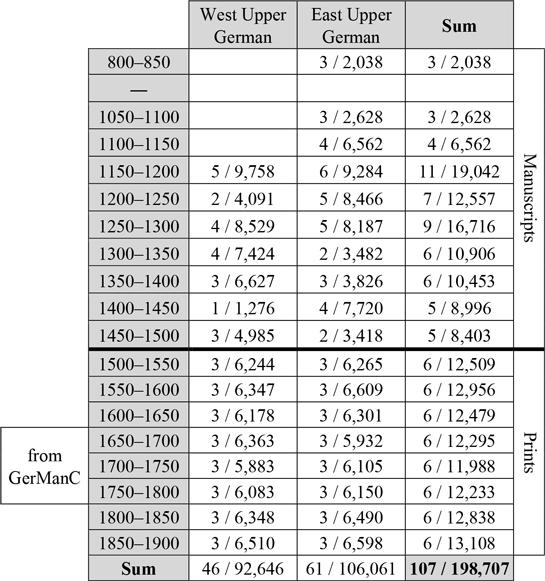

The corpus for this study consists of German sermons from the Upper German dialect area dated between 800 and 1900.Footnote 13 The corpus design follows the structure of the German Manchester Corpus (GerManC), which contains texts of multiple genres from all major regions, covers the time from 1650 to 1800 and is balanced with regard to region and time periods. With respect to the years 1650–1800, the corpus used in this study is identical with the Upper German sermons portion of GerManC. The corpus size and structure are displayed in table 1. The total size of the corpus is 204,780 words. Not counting passages in Latin, it comprises 198,707 words.

Table 1. Corpus size and structure (number of texts/word count without Latin passages).

Like GerManC, the corpus is divided into time periods of 50 years. Between 800 and 1500, each 50-year period is represented by up to eleven extracts of about 2,000 words each (depending on availability), taken from manuscripts from the West and East Upper German dialect areas.Footnote 14 Up to 1150, all the texts in the corpus are from East Upper German because no West Upper German texts are available, and for the time between 850 and 1050 there are no texts at all as a result of the transmission gap. From 1500 onward, the corpus consists of printed sermons. For each 50-year time period, six texts were selected (three for West and East), and extracts of about 2,000 words from each text were added to the corpus.Footnote 15

3. Analysis and Results

In order to assess the usage of the adnominal genitive in the sermon corpus on a general level, the frequency of its use across time is analyzed by counting all instances of adnominal genitives. This includes cases of discontinuous constructions (see Näf Reference Näf1979:246, Reichmann & Wegera Reference Reichmann and Wegera1993:335) where the genitive is clearly attributive (as in Als nůn die zyt erfüllet ist des goͤtlichen radtschlags ‘now that the time of the divine plan is fulfilled’; West Upper German 1522). Partitive genitives and fixed expressions were not included, in line with most other studies on the adnominal genitive (for example, Carr Reference Carr1933, Kopf Reference Kopf2018b). Adnominal genitives in structures where two or more adnominal genitives are concatenated recursively were counted individually.

The distinction between a prenominal genitive construction and a compound is not always clear (see Reichmann & Wegera Reference Reichmann and Wegera1993:338). Kopf (Reference Kopf2018b:110–170) provides a thorough discussion of how (and to what extent) the two can be distinguished. The distinction is particularly difficult during the time of the emergence of so-called uneigentliche ‘improper’ compounds (a type of compound formed through reanalysis of prenominal genitives), when orthographical practice was not consistent.Footnote 16 Improper compounds contain a linking element that is often not distinguishable from genitival inflection. Because this is a process of grammaticalization, the uncertainty is to an extent intrinsic, but the ambiguous cases are, in fact, rather limited. They may be divided into three types (see also Reichmann & Wegera Reference Reichmann and Wegera1993:338–339) attested in the corpus: First, there are cases such as (bei) der stadt pforte ‘(near) the city gate’ (Ebert Reference Ebert1986:93), where the reference of the article is unclear. Such instances are rare in the corpus; they were disregarded as ambiguous (Kopf’s Reference Kopf2018b:76 “bridge constructions”). Second, there are cases without any article or determiner, such as (von) wîbes lîb ‘from woman’s womb’ (West Upper German 1450–1500). These cases were not treated as genitive constructions because the first element is arguably not a full noun phrase with its own reference (see Kopf’s Reference Kopf2018b criterion of specificity).Footnote 17 Third, there are cases in which the article agrees with the head noun, such as daz engels gesange ‘the song of angels’ (West Upper German 1250–1300). These cases were discarded as compounds, too, because the genitive does not constitute a full noun phrase. Cases where the genitive is a one-word noun phrase, such as personal names or Gott ‘God’, which is used without an article, as in den adams ual ‘Adam’s downfall’ (West Upper German 1150–1200) or daz gotes wort ‘the word of God’ (East Upper German 1300–1350), were counted as genitive constructions. Instances with names are extremely rare, but instances with the lexeme Gott were quite frequent long before the emergence of improper compounds. Paul (Reference Paul2007:330) argues that in Middle High German these cases should be analyzed as genitive constructions; Ebert (Reference Ebert1986:93) and Reichmann & Wegera (Reference Reichmann and Wegera1993:338–339) imply the same for Early New High German. For this study, only cases where the two nouns were spelled as separate words were counted (see Kopf Reference Kopf2018b:151–155 for a discussion of the spelling criterion), which is a mere heuristic but leads to a cut-off point around 1500, roughly when improper compounds emerged (see Ágel Reference Ágel, Besch, Betten, Reichmann and Sonderegger2000:1859).

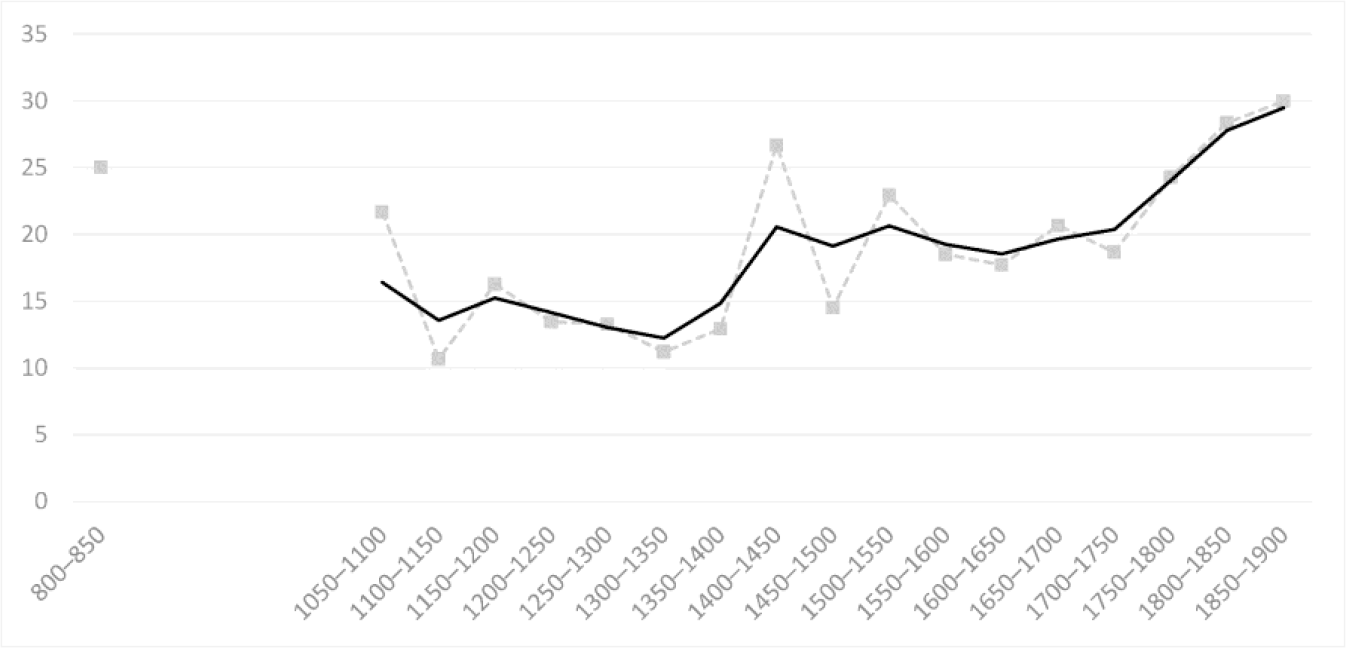

Because the text sizes in the individual time periods are not uniform, especially for the manuscript subcorpus, the frequency of adnominal genitives per 1,000 words is considered. The black dots in figure 5 represent the values for individual texts, and the grey squares connected by a dotted line indicate the weighted average for each time period (that is, the total number of occurrences per 1,000 tokens across texts).

Figure 4. Adnominal genitives per 1,000 tokens per text (black dots) and per time period (dotted line) (N=3755).

While there is a degree of dispersion among the texts, which reflects the variation within the individual timespans, the development of the average indicates that there are some overarching tendencies. Although the average is affected by some statistical fluctuations, they are not necessarily meaningful and can be regarded as noise. In order to identify overall trends and counterbalance fluctuations, the data were subjected to temporal kernel density estimation, which leads to a smoothing effect. This procedure helps stabilize numbers across time and compensate for statistical noise. Temporal kernel density estimation is, in effect, a temporally weighted implementation of a moving average, which is a common tool for smoothing patchy data along time (Blaxter Reference Blaxter2015, Lameli Reference Lameli2018). Kernel density estimation is a popular method for stabilizing scarce or unsystematic data in order to assess trends in the underlying population better. It is typically used spatially in dialectology (see Pickl et al. Reference Pickl, Spettl, Pröll, Elspaß, König and Schmidt2014, Pröll et al. Reference Pröll, Pickl, Spettl, Schmidt, Spodarev, Elspaß, König, Kehrein, Lameli and Rabanus2015:175–180), but it can also be applied in diachronic studies (for example, Blaxter Reference Blaxter2017:106–107). In kernel density estimation, the individual data points are distributed across all other data points in such a way that closer data points have a larger weight in relation to each other than data points that are further apart. This weighting is defined by a so-called kernel function. In this case, the Gaussian distribution was used as kernel function and was further weighted by the individual sample sizes. The resulting smoothing effect depends on the so-called bandwidth h, which determines the distribution’s standard deviation, that is, how far it is spread out in time—a higher bandwidth results in a stronger smoothing effect. For this application, a bandwidth of 50 years was chosen, which leads to a gentle but effective smoothing. In figure 5, the (dotted) data line indicating the underlying raw average from figure 4 for reference is complemented by a (solid) trend line, which is the result of temporal density estimation.

Figure 5. Adnominal genitives per 1,000 tokens across time (N=3755, h=50y).

Generally, it can be seen that Fleischer & Schallert’s (Reference Fleischer and Schallert2011:94–100) picture of a decline of the adnominal genitive does not seem to apply here. Neither can Dal’s (Reference Dal2014:26) assertion that the adnominal genitive strongly declined in the New High German period be confirmed. Rather, the opposite seems to be the case: From 1050 onward, the general trend of the usage of the adnominal genitive is an upward one.Footnote 18 At least for sermons, there is no evidence of genitive loss; on the contrary, usage of the adnominal genitive increases, corroborating the assessments of Admoni Reference Admoni1987, Ágel Reference Ágel, Besch, Betten, Reichmann and Sonderegger2000, Reichmann Reference Reichmann, Berthele, Christen, Germann and Hove2003, von Polenz 2013, and Niehaus Reference Niehaus2016, all of which explicitly concern Schriftsprache [‘language of writing’].

Overall, three main stages of development can be discerned. Up until 1400, usage is fairly stable, showing only a slight decline, which might reflect a decreasing usage in spoken language, at around 13 instances per 1,000 tokens. From 1400, usage rises quite abruptly to about 20 per 1,000 tokens, at which point it becomes relatively stable again (not taking into account the pronounced swings in the raw data).Footnote 19 From 1750 onward, usage increases further, but this time gradually, and reaches almost 30 per 1,000 tokens by 1900.

Such a dramatic rise in the usage of the adnominal genitive as such must at least partly be associated with an adoption of new syntactic functions. What functions these were exactly is difficult to establish because adnominal genitives represent only one of a range of syntactic means to integrate constituents that can be expressed as noun phrases. This range not only includes the established Ersatzformen ‘surrogate forms’ (a term, which, questionably, implies that the genitive is some sort of default) associated primarily with spoken usage, such as the possessive dative or prepositional phrases with von (see Hartweg & Wegera Reference Hartweg and Wegera2005:174, Scott Reference Scott2014:44–47), but also less obviously related forms, such as adjectives, relative clauses, compound elements, etc. instead of nouns.Footnote 20 The exact trade-offs between the adnominal genitive and alternative means of expression are therefore hard to establish; they are, however, not central to the present study as it is not crucial which forms the genitive was in competition with.Footnote 21

A division into personal, nonpersonal, and proper nouns is often regarded as relevant for the position of the genitive relative to the noun (for example, Carr Reference Carr1933, Demske Reference Demske2001). Sometimes more detailed classifications are used, for example, by dividing nouns referring to nonhumans into abstract and concrete (see, among others, Ebert Reference Ebert1988). The relevance of these categories for the position of the adnominal genitive raises the question of whether they have an impact on its usage frequency as well. In order to explore the relevance of different types of nouns for genitive usage and its development over time, I use Silverstein’s (Reference Silverstein and Robert1976) animacy hierarchy, which distinguishes between proper, human, animate, and inanimate nouns, with a further distinction between abstract and concrete inanimate nouns added later (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Greville, Sebastian Fedden and Marriott2013, among others). Figures 6 and 7 show the frequency of usage for the individual categories (all animate genitives in the corpus refer to persons). It is noteworthy that the first, sudden increase in use is largely due to a rise in the number of genitives of inanimate abstract nouns, which on the whole account for 42% of all adnominal genitives. The stability of genitives of animate nouns during that time indicates that the prototypical relation of the genitive—that of possession—is not affected by this development; rather, the genitive is increasingly used to modify noun phrases with nouns referring to abstract concepts. The second, more gradual rise applies to both abstract and animate nouns, but not concrete and proper nouns. The changes in the frequency of genitives of proper nouns are also noteworthy (see Pickl 2019b for the relationship between type of proper noun and position of the adnominal genitive); their increased usage from 1400 onward may be indicative of genre change, with more personal names being used in the Reformation and the heyday of the Leichenpredigten ‘funeral sermons’.

Figure 6. Proper nouns (N=901), animate nouns (N=917) (h=50y).

Figure 7. Inanimate concrete nouns (N=247), inanimate abstract nouns (N=1,588) (h=50y).

As outlined in section 1, the adnominal genitive appears in two distinct syntactic variants: a prenominal one (as in der menschen suͤnd ‘the sin of humans’; East Upper German, 1557) and a postnominal one (as in vergebung der suͤnden ‘forgiveness of sins’; East Upper German, 1557). While there is variation between these two variants across the history of German, which is subject to a number of internal and external factors, the postnominal position has been the clear default since the 15th century at the latest (see Pickl 2019b). The frequency of use of pre- and postnominal genitives viewed separately (figure 8) shows that the increase in the use of the adnominal genitive after 1400 is exclusively due to postnominal forms, with the prenominal genitive even declining at the same time. The proportional shift toward postnominal forms (see, for instance, Ágel Reference Ágel, Besch, Betten, Reichmann and Sonderegger2000:1858, Nübling et al. Reference Nübling, Dammel, Duke and Szczepaniak2017:129–130), therefore, was mainly a result of their rise in absolute numbers rather than of the replacement of prenominal forms by postnominal ones.

Figure 8. Prenominal genitives (N=787), postnominal genitives (N=2968) (h=50y).

The postnominal genitive had some structural advantages over the prenominal form because it had fewer restrictions (see Pickl 2019b:193–194). Prenominal genitives cannot be used with an indefinite head noun; this restriction, however, does not apply to the postnominal genitive, which can be used with definite and indefinite head nouns. Moreover, prenominal genitives block the concatenation of genitives, that is, a prenominal genitive cannot be combined with another one; by contrast, there are no restrictions on the length of postnominal genitive chains, and examples with two or more genitives are found frequently (as in dieser Betrachtung deß hohen vnnd grossen Wercks Menschlicher erloͤsung ‘this consideration of the sublime and grand deed of human salvation’; East Upper German, 1663). The availability of the postnominal genitive, therefore, was a necessary prerequisite for the expansion of the adnominal genitive overall.

Between 1500 und 1700, there was a temporary revival of prenominal forms, which affected the numbers of postnominal forms negatively. This may be related to the rise of the improper compound (see the discussion above; Kopf Reference Kopf and Tanja Ackermann2018a, Reference Kopf2018b:218, 311), which took place during that time. As discussed above, this type of compound emerged as a result of the reanalysis of the closely related prenominal genitive construction (see Kopf Reference Kopf2018b:188–192). At the time there was a high degree of structural ambiguity between prenominal genitives and improper compounds (see Kopf Reference Kopf2018b:189–190), which was necessary for the reanalysis to take place.Footnote 22 This may have led to an increased use of prenominal genitive constructions in a state of syntactic insecurity. This state of structural ambiguity was resolved ca. 1700, when bridge constructions became rare and the distinction between improper compounds and prenominal genitives became clearer (see Kopf Reference Kopf2018b:400).

The variation between the East and West Upper German parts of the corpus is minimal (see Pickl 2019b:189-190 for areal differences regarding the position of the genitive). This indicates that these findings, even though restricted to the southern part of the German-speaking area, may be representative of a larger area.

4. Discussion

Scott (Reference Scott2014:315) describes a “resurgence” of the adnominal genitive in German (and Dutch) following the 15th century after a period of gradual decline; a similar pattern is found in the sermons data, with a slight gradual decrease in genitive usage up to 1400 and a sudden rise in the 15th century.Footnote 23 Scott (Reference Scott2014:315) argues that this resurgence “was affected by the codification of German and Dutch” and claims that “explicit prescription is an important factor in the preservation of case morphology in a language undergoing deflection.” He goes on to say, however, that “explicit codification and moves towards standardisation cannot have been the only reasons” (Scott Reference Scott2014:316) for this because the revival of the genitive predates the first grammars (Scott Reference Scott2014:315, 320, 329). The fact “that, even before standardisation was fully underway, the genitive was already part of the convention for formal written language” (Scott Reference Scott2014:224) is offered as an explanation; “it is, however, unclear why the genitive case […] was chosen over its competitors long before it had been specifically chosen as the prestige variant” (Scott Reference Scott2014: 329). In the following, I argue that the genitive’s association with formal written language before explicit standardization set in was a result of its demise in spoken language at a time when a distinct written variety was starting to form.

It is striking that the sharp rise in the use of the adnominal genitive in written language after 1400, which is even more distinct in the raw numbers, coincides with the time when, according to Behaghel, the genitive in spoken language was lost, which he dates to the 15th century (see section 1). It therefore has to be noted that, if Behaghel’s dating is correct, this sudden increase in the written sources happened roughly at the same time as the adnominal genitive disappeared from spoken language. This means, first, that this gain of about 50% is largely a written phenomenon, and second, that it is likely the two events are in some way connected. How can the loss of a feature in spoken language and its upsurge in written language at roughly the same time be reconciled? In the remainder of this section, I argue that this seemingly contradictory development can be explained best by using the model of polarization. As Barbour & Stevenson (Reference Barbour and Stevenson1990:161) have pointed out (see section 1), the genitive today can be considered a marker of formal standard German, which is closely related to written discourse. As such, it is a polarized, written feature. It seems likely that this is ultimately a consequence of its disappearance from spoken language in the 15th century, as I explain below.

When the genitive was lost in spoken language, texts written before the loss remained in use further on, and at least some new texts continued the written tradition, maintaining a style that was then associated with written texts through copying, the use of written formulas, and so on.Footnote 24 In addition, texts remained in use long after they had been written.

As a consequence, there was a time when the genitive was still found regularly in written texts but was already uncommon in spoken language. This contrast meant that the adnominal genitive appeared polarized: Up to then a feature found in spoken and written discourse with frequencies that were probably not very distinct from each other, it had now disappeared from the former but persisted in the latter. It thus became an indicator—or 1st-order indexical feature (according to Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003)—of writing. In addition, the loss of oral competence in using the genitive could have already led to the over-generalization of the genitive as a written feature because it was no longer rooted in oral probabilistic competence. In effect, the resulting over-application already boosted the use of the genitive.

As a result of this emerging contrast, the genitive became associated with written language, which in turn was associated with formality, especially through releases of the chanceries. Thus, by early modern times the genitive had become a feature not only of formal, elevated style (see Niehaus Reference Niehaus2016:182).Footnote 25 As such, the genitive could then re-enter spoken discourse as a marker of formal, or written-like language (first in such cases where speech was based on written language or imitated its style), which signaled its indexicalization.Footnote 26 Figure 9 illustrates that the decreased use of the genitive, with written language lagging behind spoken language, first led to a slightly polarized situation by 1400. The successive upswing in written language can be explained by the genitive’s indexicalization as a written marker and its new function as a stylistic device.

Figure 9. Sketch of the processes leading to the polarization of the adnominal genitive in German.

The availability or emergence of a contextual written-like style that can be realized in speaking or writing is fundamental for the genitive becoming a marker of that style (in the sense of Silverstein’s (Reference Silverstein2003) 2nd-order indexicality). Such a written-like style was indeed materializing around the time of the genitive’s upsurge, which is interpreted as an indicator of its indexicalization. This new stylistic variety emerged against the backdrop of increased literacy, a massive expansion of production, and a growing societal significance of written language in the 15th century (Erben Reference Erben1989:8, von Polenz Reference Andreas Gardt1995:145, Hennig Reference Hennig2009:41).Footnote 27 Its development was catalyzed by the availability of cheap paper instead of the more expensive parchment and accompanied by new sociopragmatic functions of written language and the formation of a distinct written style (Erben Reference Erben1989:8–9, 2004:1585; von Polenz 1995:44–45, 2000:114–116). The emergence of this new stylistic variety marks the beginning of the enregisterment of what would be later referred to as Schriftsprache ‘language of writing’—a variety of language with its own distinctive set of linguistic features that became the foundation for the development of the standard variety.Footnote 28

The emergence of a new written style led to an opposition between this new variety and an “oral style” (Zeman Reference Zeman and Antović2016) that continued previous spoken usage of language. While the written and spoken media are dichotomic, the written and spoken styles are polarized. Mattheier (Reference Mattheier1981:298) postulates polarizations in the late Middle Ages that had led to a diversified, vertically organized system (see discussion on p. 168) of varieties and their evaluations (“Sprachwertsystem” [‘language value system’]) by ca. 1400. The dichotomy between the two media, along with their respective universal features, is one of a number of dimensions of “situational characteristics” (Biber & Conrad Reference Biber and Conrad2009), “conditions of communication” (Koch & Oesterreicher 2012), or “discourse parameters” (Schneider 2013), that is, conditions of language production that have an impact on the form of language. These conditions form “a multi-dimensional space between two poles” (Koch & Oesterreicher 2012:447) and give rise to Koch & Oesterreicher’s (2012) prototypical poles of language of immediacy and language of distance, which, in literate societies, are associated with spoken and written language, respectively. As the distinction between spoken and written language became more and more pronounced, the respective styles became polarized along Koch & Oesterreicher’s scale between immediacy and distance, which led to the emergence of two distinct varieties at the two poles. In this incipient process of enregisterment, more and more features “become recognized (and regrouped) as belonging to distinct, differentially valorized semiotic registers” (Agha Reference Agha2007:81). In this case, the features are recognized as belonging to written language and spoken language, so that both varieties increasingly consist of secondary (historically contingent) markers in addition to primary (universal) markers of speech and writing. This leads to an increasing divergence and, finally, separation of spoken and written language. The new distinct written variety becomes observable in the 15th century (von Polenz 2000:114–115) and also manifested itself in genres that were hitherto meant for oral reproduction through reading aloud (von Polenz 2000:115).

This process facilitated the emergence and spread of reading sermons, which were intended to be read by the congregation rather than listened to, and which later were produced specifically for print. The sermons, as a result of this pragmatic switch from oral to written reception, underwent a shift toward the new written style, including the adnominal genitive as one of its features. The genitive was part of the initial formation of the written variety as it underwent incipient polarization between speech and writing at the time. Its polarization was then reinforced through its indexicalization as a marker of written German, a function the genitive performs to this day.

The divide between written and spoken language deepened further over time, leading to their dissociation (Reichmann Reference Reichmann, Berthele, Christen, Germann and Hove2003:43). This dissociation is reflected in a profound reorganization of language structure, variation and usage from a more horizontal to a more vertical orientation. Reichmann (Reference Reichmann1988, Reference Reichmann, Berthele, Christen, Germann and Hove2003) refers to this process as verticalization, a pervasive sociolinguistic reorganization in which “prinzipiell jede sprachliche Einheit” [practically every linguistic unit], including the adnominal genitive, underwent a sociolinguistic and stylistic reallocation and evaluation by the language users between the 15th and the 17th century (Reichmann Reference Reichmann1988:175).Footnote 29 The expansion of the adnominal genitive in written language was a result of this upheaval (Reichmann Reference Reichmann, Berthele, Christen, Germann and Hove2003:47) and went hand in hand with its becoming a marker of the variety referred to as Schriftsprache. Against this background, it is not surprising that the language of sermons was transformed by verticalization and by the inherent ideology of logic and correctness of Schriftsprache, which eventually also affected the oral rendition of sermons. As a consequence, grammatical correctness and logic could even supersede clarity as the guiding principle of written and oral language production (Knoop Reference Knoop and Oellers1988, Reichmann Reference Reichmann, Berthele, Christen, Germann and Hove2003:44–45).

The second, more gradual rise of the adnominal genitive in sermons happened after 1700 in the context of a profound and wide-reaching change in literacy and the increased significance of writing in society in the mid-18th century, which was determined by a number of factors (Knoop 1994:867–869, Hennig Reference Hennig2009:44–45). The 18th century as the Age of Enlightenment is often seen as pivotal for the development of literacy among the German population, and for a transformation of the role of writing in society and its relation to speaking (Knoop 1994:867–869). Printing production doubled, and newspapers and periodicals became more widespread. The 18th century saw the advent of compulsory schooling in most German-speaking territories and mass literacy among the majority of the rural population (Knoop 1994:878).

All of this had a tremendous impact on reading habits in quantitative (to an extent that concerns of Lesesucht ‘reading addiction’ were voiced) and qualitative terms (the reading practice shifted from a more social event, where most recipients would listen to one member of the group reading aloud, to a more solitary, quiet exercise). This transformation was dubbed Leserevolution ‘reading revolution’ by Engelsing (von Polenz 2013:37). The increase in the use of the genitive after 1700, which reaches its high point in the 19th century (Admoni Reference Admoni1987, Niehaus Reference Niehaus2016), can be seen as a manifestation of a more general, gradual deepening of the division between spoken and written language during that time (Admoni 1985:1538).Footnote 30

The incremental expansion of the adnominal genitive in writing as a result of polarization did not affect all types of adnominal genitives alike. Genitives of animate and inanimate concrete nouns do not appear to have changed a great deal in frequency over most of the investigation period. Inanimate abstract nouns, however, are clearly the type primarily affected by the upswing of the genitive on the whole: Of the genitive forms of all types of nouns, their trajectory shows most noticeably the pattern of a staggered expansion that can be observed for the adnominal genitive on the whole. Taking into account the large proportion of genitives of abstract nouns (42%), the polarization of the adnominal genitive and its indexicalization as a written feature were clearly borne by abstract nouns. This conclusion ties in with the finding that the postnominal form of the genitive shows largely the same behavior over time as adnominal genitives in general and those of abstract nouns in particular: Overall, they show the clearest and most consistent tendency toward postposition in the corpus (94% compared to 68% of the other types); in fact, abstract nouns make up 51% of all postnominal nouns in this corpus, but only 11% of all prenominal nouns. These proportions corroborate the hypothesis that it is abstract nouns—more specifically, the postnominal genitives of abstract nouns—that drive the expansion of the construction, while other types of nouns referring to entities with higher degrees of animacy are less central to the development. In sum, the polarization of the adnominal genitive is mainly due to the increased usage of postnominal genitives of abstract nouns, while animate and proper nouns only seem to follow this trend from ca. 1750 onward.

The central role of abstract nouns might stem form the fact that abstract genitives can be used to express a wide range of conceptual relations in a compact manner, as in die Vergebung unsrer Sünden ‘the forgiveness of our sins’ (West Upper German, 1792), an idea that would otherwise be expressed using other, usually more complex syntactical means. While the same is true for the genitives of other types of nouns, there are limits to how many genitives can be used in a given text if, for instance, the discourse contains no reference to humans. In other words, the upper threshold for genitives of proper, animate, and inanimate concrete nouns is more clearly defined than that of abstract concepts. The fact that more syntactic restrictions apply to prenominal genitives than to postnominal ones (Pickl 2019b) further explains why it was the postnominal form of the genitive of abstract nouns that was predominantly used as a marker of written language.

5. Conclusion

In written German found in sermons, the usage frequency of the adnominal genitive has on the whole increased considerably since medieval times. This is remarkable given the disappearance of this feature from spoken German in the Early Modern period. This divergent development, which may seem contradictory at first, can be understood in terms of polarization between written and spoken German. It occurred at a time when sociopragmatic factors led to the formation of a distinct written style, of which the genitive was a constitutive feature: Both the genitive and the varietal spectrum were polarized between spoken and written registers. As a result, the genitive became an indexical feature of written language and formal style. This development did not apply to all types of the genitive equally: Because of their semantic and syntactic properties, postnominal genitives of abstract nouns were particularly affected. The genitive was further boosted in the process of the verticalization of language variation, structure, and usage in German, which prepared it for its role as a feature of the nascent standard language. It became a feature of formal written German and was therefore predestined to become part of standard German once codification set in, and it gained even more prestige in the solidification of the German standard variety with the rise of an ideology of logical and grammatically correct language.

The usage of the adnominal genitive turns out to be indicative of pervasive sociopragmatic changes in the relation between spoken and written language in the history of German. These changes appear in the language of sermons as (abrupt or gradual) stylistic shifts, demonstrating how different styles shaped this genre at different points in time. As such, the findings contribute to von Polenz’ (2000:79–80) understanding of language history as “Sprachgeschichte als soziopragmatische Stilgeschichte” [language history as sociopragmatic stylistic history], which focuses on salient changes in the utilization of existing linguistic features rather than on changes in the abstract language system.

Pickl (forthcoming) shows for the 18th century that the tendencies observed in this study affected other genres as well. Further research will also have to establish whether the outlined trajectory of the adnominal genitive in German and the proposed explanations are applicable in other linguistic contexts. A closer investigation of the diachrony of other polarized features that are markers of written language today (in German and beyond) could help us better understand polarization, what typically triggers it, and its relation to indexicalization and enregisterment. While additional case studies have the potential to identify specific linguistic conditions that encourage micro-polarization, cross-feature and cross-linguistic investigations of polarization could ascertain societal preconditions leading to or inhibiting macro-polarization.