1. Introduction.

This article presents the results from an exploratory study of the theory of pluricentricity of German, with a focus on the written lexicon. Specifically, I investigate whether, and to what extent, the concept of coexisting standard varieties of German can be validated by the perceptions of nonlinguist native speakers from Austria (N=115) and Germany (N=104).

Linguists argue that the German language on the European continent is pluricentric. According to this model, there are three independent standard varieties of German, each associated with a different national center: German Standard German (henceforth GSG), with Germany; Austrian Standard German (henceforth ASG), with Austria; and Swiss Standard German (henceforth SSG), with Switzerland (Wiesinger 1988, Clyne 1992, Ammon 1995).Footnote 1 The Variantenwörterbuch des Deutschen [Dictionary of Variants of the German Language] (henceforth VWB) provides the following definition of the term:

Von einer plurizentrischen Sprache spricht man dann, wenn diese in mehr als einem Land als nationale oder regionale Amtssprache in Ge-brauch ist und wenn sich dadurch standardsprachliche Unterschiede herausgebildet haben (pp. xxxi–xxxii; emphasis, JP).

[One can speak of a pluricentric language if it is used in more than one country as a national or regional official language, and if differences in the standard register of this language have arisen as a result.]

Thus, I regard the question of whether a language has more than one manifestation of a standard register (as opposed to nonstandard regional variation) as central to the idea of pluricentricity. However, without empirical support, the idea remains a theory, put forth by linguists as a quasi “linguistic edict.” My study was constructed to explore the validity of this “edict.”

Following a recent trend of scholarship on ASG and SSG, I examined individual judgments of Austrians and Germans regarding the “standardness” of the Austrian and German written standard, as represented by 18 lexical items of each.Footnote 2 Using data obtained through questionnaires, in which 219 native speakers of German in Austria and Germany rated the standardness of the lexical items, I provide convincing empirical evidence for the validity of the pluricentric model—specifically, a “dual standardness awareness” among Austrians—which up to now has largely been theoretically postulated.Footnote 3

The empirical approach and methodology of my study were inspired in particular by the work of Preston (1989) in the field of perceptual dialectology. In the 1980s, Dennis Preston became interested in the attitudes and perceptions that nonlinguists have regarding language.Footnote 4 Seeking patterns to these attitudes and perceptions, Preston drew from methodology used in the field of cultural geography (especially Gould & White 1974). One such method was to present subjects with a map of the United States and to ask them to label the different regions of speech. In this way, Preston established the terminology that nonlinguists used and asked subjects to rate regional varieties of their native language along a differential scale, where the poles of this scale were labeled with evaluative characteristics such as “friendly” and “unfriendly,” or “correct” and “incorrect.”

Through his studies of nonlinguist perceptions, presented in Preston (1989:113–131) and elaborated on in Niedzielksi & Preston (2000:63–77), Preston concluded that the two most common associative characteristics harbored by nonlinguists were “pleasantness” and “correctness,” a finding similarly presented in Ryan, Giles, & Sebastian 1982 in the field of social psychology.Footnote 5 My study adopted the bi-polar differential scale method, as used by Preston, to determine patterns behind the attitudes and perceptions of nonlinguists regarding regional linguistic variation. For my assessment component I adopted the evaluative term “standardness” (Standardsprachlichkeit) from Ryan, Giles, & Sebastian 1982.

The present article discusses how individual native speakers of German in Austria and Germany rated the standardness of 36 lexical items designated—by dictionaries of the Austrian and German standard varieties—as representing either the Austrian or German written standard lexicon. A questionnaire served as the basis for gathering quantitative data. All 36 lexical items were presented in written form, randomized, and rated by participants on a Likert scale. Analyses consider participant characteristics (nationality, age, level of education, travel to and from Austria and Germany, and experience in linguistics), and characteristics of the lexical items (Austrian or German affiliation).Footnote 6

Section 2 of this article offers a short discussion of the ASG lexicon. Section 3 deals with methodology. Section 4 presents the quantitative results from the questionnaire in a two-part data set analysis: (i) exploring variation in responses within the German and Austrian data sets combined, and (ii) comparing responses in the German data set with those in the Austrian data set. Section 5 is a discussion of the two-part data set analysis. Section 6 discusses methodological limitations. Finally, in section 7, I bring together the major points of my study, addressing its larger significance for the field of sociolinguistics.

2. The ASG Lexicon.

Before addressing lexical aspects of ASG, including a discussion of the principal lexical codex for ASG, the Österreichisches Wörterbuch [Austrian Dictionary] (henceforth ÖWB), a short discussion of key terms must be included. This article regularly employs the expressions variety, standardness and/or standard language, national variety, and national variant. It is thus important to clarify their meaning.Footnote 7 The explanations below apply to the terms as I use them henceforth.

My understanding of the term variety follows Chambers et al. 2002, where it is broadly interpreted as any manifestation of externally or internally rule-governed human language, ranging from dialect to standard. As for standardness and/or standard language, I adopt the view put forth in Milroy & Milroy 1991 that the concept of standardness is largely ideological in nature. However, when a certain variety of a language acquires a more prestigious perception, this variety can be standardized by external authoritative sources, such as model speakers, prescriptive texts, and polities.

For reasons that have still not been clarified by its authors, the ÖWB does not employ the term national variety in connection with the standard variety of German in Austria. Rather, it employs the term regional standard:

Unter regionalem Standard versteht man sprachliche Ausprägungen, die zwar der Standardsprache angehören, aber in der Verbreitung begrenzt sind, entweder nach Staatsgrenzen (Österreich, Schweiz, Deutschland) oder nach meist größeren Sprachregionen (z.B. Nord-deutschland, Ostösterreich, Westösterreich, Bayern) (p. 737).

[Under a regional standard is meant those linguistic manifestations which belong to the standard language, but which are limited in their distribution, either according to national boundaries (Austria, Switzerland, Germany) or according to mostly larger dialectal regions (for example, North Germany, East Austria, West Austria, Bavaria).]

I accept this notion that ASG can be considered a regional standard. However, I would like to go beyond this broad “regional” or “areal” classification and argue in line with Clyne 1992, 1995 and Ammon 1995 that ASG is a regional standard specific to a nation state. It is thus a national variety. Furthermore, this term encompasses only those national variants, or (phonological, lexical, or grammatical) linguistic items, which have been codified. This idea that a national variety includes the sum of all national variants is also in line with Ammon 1995. When he uses the term national variety, he means all codified grammatical, phonological, and lexical “national variants” taken in total:

Nationale Varianten einer Sprache sind also im Rahmen der vor-liegenden Untersuchung so definiert, daß sie für die verschiedenen Nationen der betreffenden Sprachgemeinschaft gelten … Wenn ich also im weiteren von den nationalen Varietäten spreche, so meine ich damit nur Standardvarietäten, keine Nonstandardvarietäten (p. 69).

[Within the scope of the present study, national variants of a language are therefore defined as such, if they are valid for various nations of the relevant language community … Whenever I henceforth speak of national varieties, I thus mean by this only standard varieties, and not nonstandard varieties.]

Thus one can speak of an individual Austrian phonological, grammatical, or lexical variant. As mentioned above, my study examined the perceptions of 18 of the latter. However, by taking all of the codified Austrian lexical variants in sum, one can speak of an Austrian standard lexicon. Scholars have posited over 3,000 ASG words (Ammon 1995, Wiesinger 1995, Markhardt 1993, 2002).

Unlike the areas of phonology, morphology, syntax, and pragmatics, there is substantial scholarship dealing with the ASG lexicon. Wiesinger (1995) argues that there are six “Bezeichnungs- und Bedeutungs-gruppen” [categorization and semantic groups] that capture the nature of the ASG lexicon:

i) Upper German

ii) Common Bavarian

iii) Actual Austriacisms

iv) Inner-Austrian East-West division

v) Regional Expressions

vi) Common German Word

More specifically, scholars have discussed the criteria against which Austrian German lexical items should be judged as “reference work-worthy.” Moser (1995), Ebner (1995), Wiesinger (1995), Reiffenstein (1995), Scheuringer (1997), and Schrodt (1997) debate a number of questions.

First, they consider to what extent a word's transnational geographic distribution should matter. Can a word that is also valid in Bavarian colloquial speech really be called an Austriacism, or are the only real Austriacisms those terms exclusive to Austria? Second, they ask to what extent geographic distribution of words within Austria should matter. That is, should a word such as Fleischhauer ‘butcher’ be posited as the standard Austrian lexeme even though it is not valid in Tyrol or Salzburg, where the variant Fleischhacker is predominately used? They continue with a debate over the extent to which the ASG lexicon should include words and expressions from colloquial and dialectal registers. On the one hand, a number of scholars argue against what they view as a degradation of a prestige variety (Wiesinger 1980). On the other hand, as the controversial 35th edition of the ÖWB showed in 1979, there are linguists in Austria who feel that such variants should be “raised” through codification to the status of the standard (Clyne 1995). While linguists continue to debate these matters, an ASG lexicon has, nevertheless, emerged within the last sixty years, primarily in the form of the VWB, Ebner's Wie sagt man in Österreich? [How do you say this in Austria?] and, above all, the ÖWB.

First published in 1951, the ÖWB was billed as “[e]in Wörterbuch der guten, richtigen deutschen Gemeinsprache” [a dictionary of the good, correct German common language] with a focus on the “österreichischen Besonderheiten” [Austrian characteristics], while including “zahlreiche allgemein verwendete Wörter der österreichischen Umgangssprache und der österreichischen Mundarten” [many generally used words of Austrian colloquial speech and Austrian dialect] (Reiffenstein 1995:158). Since its first publication, there have been 41 state-subsidized editions, which leading scholars have consistently scrutinized.

The controversial 35th edition is a good example. Published in 1979 as “newly conceptualized” (ÖWB 1979:9), it quickly became the focus of a debate concerning the status of ASG, language planning, language politics, and issues of national identity.Footnote 8 It was more than a third larger than its predecessor, containing a 33% increase in total lemmas (Reiffenstein 1995:159). However, scholars noted that many of the newly included lemmas contained no markings designating register or region. Wiesinger (1980) undertook an empirical investigation of select lexical decisions that the (at the time, still anonymous) authors of the 35th edition had made. In a survey of 87 stylistically unmarked words, conducted among 171 Austrian university students, Wiesinger's study revealed that the students considered these items as nonstandard in the written form, though acceptable in colloquial speech. The dictionary, he argued, represented an unsystematic, unmarked mixing of regionalisms and registers. Consequently, Wiesinger interpreted the 35th edition as a product of language politics, rather than linguistic inquiry; it did not, he argued, accurately reflect sociolinguistic realities in Austria.

Consequently, some Austrian scholars described the 35th edition of the ÖWB as “separatist” and “standardizing” (Dressler & Wodak 1982). Since “[i]t no longer concealed Austrian distinctiveness but rather accentuated it,” scholars sided with Wiesinger, regarding the codex as a sign of government-sponsored language planning (Clyne 1988:336). It thus generated a lively discussion—both in the public and among scholars—on the form and status of the Austrian national variety. These conver-sations, and especially the criticism, were reflected in the 36th edition, released in 1985: “[It] retreated from some of the planning reforms of its predecessor” (Clyne 1988:339). This edition sought a balance in its choice of entries and stylistic designations: It continued to express the Sonderprägung [distinct nature] of the Austrian variety, while striving to satisfy its linguistically more conservative critics. The authors of subsequent editions, including the most current (41st), have maintained this conservative approach.Footnote 9

3. Methodology.

In the present section, I address methodology: I discuss participants, the construction of the questionnaire, the type of data, and the process of data collection and analyses.

3.1. Participants.

My study includes a nearly even number of Austrians (N=115) and Germans (N=104). Almost all Austrians are from East Austria (N= 112).Footnote 10 The Germans were evenly distributed between Northern Germany (N=30), Central Germany (N=39) and Southern Germany (N=41).Footnote 11 Regarding age, there is a concentration of 20–40 year olds (N=129), with the remaining age groups (10–20 and 40–60) evenly represented. Frequency of travel is evenly spread out, though there are fewer respondents who travel very frequently between Austria and Germany, that is, “more than once a month” or “more than three times a year” (N=20) than respondents who travel “almost never” or “never” between the nations (N=73). Next, a 53% (N=116) majority of respondents reports either currently attending or having completed an education at the post-secondary level. Finally, the participants' background in linguistics is less evenly distributed. The majority of participants reported either having “once learned something about linguistics in school” (N=59), “never having learned about linguistics at school and not interested in the topic” (N=67), or “not knowing what linguistics is” (N=23). In general, the participants in my study are nonlinguists under 40 years old, who do not frequently travel between Austria and Germany, and who are rather well educated.

3.2. Data Gathering Procedure.

Data were collected via email, through a network of friends and personal contacts, in the form of a questionnaire. The goal of this questionnaire was to present individual participants with written tokens of the Austrian and German national varieties, and to elicit judgments regarding the standardness of the tokens. A Cronbach alpha of .872 served as an index of the quantitative reliability of the questionnaire, computed by scale (standardness) and national variety items (total number of ASG and GSG items).

As mentioned above, the first part of the questionnaire elicited personal information in multiple-choice format on the respondent's nationality (that is, in which country they reported to have grown up), age, frequency of travel between Austria and Germany, current or last educational level, and experience in linguistics. The second section of the questionnaire presented the participant with 18 ASG and 18 GSG lexical variants, and 7 distracter items, for a total of 43 tokens. Participants were asked to rate the words on a scale of standardness with options between 1=umgangsprachlich/nicht standardsprachlich [colloquial/not standard]) and 4=standardsprachlich [standard]. If the participant was not familiar with the word, they were asked to rate it as 5 “Das Wort ist mir unbekannt” [I'm not familiar with the word].

3.3. Token Selection.

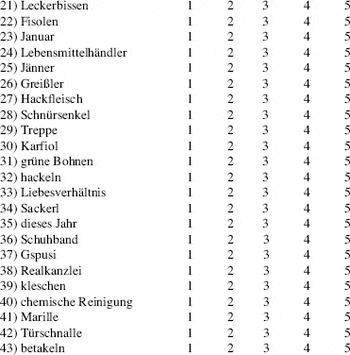

All ASG items were selected on the basis of three criteria. First, they were not marked (in terms of regional or register usage) in their chief lexical national codex.Footnote 12 Second, they were noted in the scholarship as an Austriacism. Third, they were not low-frequency or special technical terms.Footnote 13 The GSG items were selected on the basis of the first and third criteria.Footnote 14 Separate distracter items (N=14), designed to veil from participants the study's scholarly goal, were selected for both the Austrian and German groups. These items were marked as “umgang-sprachlich” [colloquial] in their corresponding national lexical codex. Table 1 below provides a list of the tokens.

Table 1. List of tokens.Footnote 17

Finally, I would point out that the number of tokens selected for the present study, though adequate for the statistical analyses run on the data, represents a small percentage of the total number of ASG lexical items posited by scholars.Footnote 15 I do not claim that these 18 items are representative of the entire ASG lexicon. While the number of tokens is sufficient here, for the purposes of an exploratory endeavor, subsequent studies should include a larger corpus for evaluation.Footnote 16

3.4. Data Analysis.

I used the statistical analysis software SPSS to tabulate and analyze responses on the quantitative questionnaire. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were used. While the specific analytic methods together with the presentation of results are explained in section 4 below, table 2 provides a list of the inferential statistical analyses used, a brief description of each analysis, and an example of how I applied it to my data.

Table 2. Inferential statistical analyses.

4. Presentation of Results

I now present the results from the questionnaire, divided into two analytic sets: an exploration of variation within the full data set (that is, German and Austrian ratings combined) and a comparison of national data sets (that is, German nationals and Austrian nationals). Each analytic set pertains to a specific research question that will be used as a basis for discussion in section 5.

4.1. Variation Within the German and Austrian Data Sets.

This analytic set addresses the following research question (henceforth RQ1): How much do the rater background variables of nationality, age, mobility, level of education, and experience in linguistics contribute to variation in ratings of written ASG and GSG lexical items, respectively, in terms of standardness? The motivation behind RQ1 is to explore the basis of the pluricentric argument for the German language. With the pluricentric model as a base, the expectation was that the variable of nationality (that is, German or Austrian) would contribute most to variation in ratings of the standardness of ASG and GSG lexical items. The remaining variables, whether taken individually or together, would have a less significant effect on participants' answers. Should this be the case, it would support the thesis of dual standard varieties of German, in this case—a German Standard German and an Austrian Standard German.

To contextualize the relative contribution of nationality to variation in standardness ratings, four additional independent variables relating to the raters' background (age, mobility, level of education, and experience in linguistics) were included in a step-wise regression analysis, and variation was assessed relative to two dependent variables: standardness ratings of GSG and ASG lexical items, respectively. Standardness was measured on a 4-point scale, where a rating of 1 equaled the label “colloquial/not standard” and a rating of 4 corresponded to the label “standard.” Results are displayed in tables 3 and 4.

Table 3. Contribution of rater background variables to variation in ratings on all ASG items for standardness.Footnote 18

Table 4. Contribution of rater background variables to variation in ratings on all GSG items for standardness.Footnote 19

Looking at the variation within the entire data set for ratings of standardness, it is clear that over half of the variation in the ratings of the ASG items was attributable to the variable of nationality alone. For the GSG items, the variable of nationality also showed itself to be the greatest contributor to the variation. Nevertheless, the smaller percent-wise contribution of this variable in ratings of GSG items, as compared with ratings of ASG items, indicates that although nationality was the strongest predictor variable for both GSG and ASG items, it mattered more for the ASG items.

4.2. Comparing National Data Sets (Germans and Austrians).

For the second of the analytic sets I pose the following research question (henceforth RQ2): Do German and Austrian respondents rate written ASG and GSG lexical items, respectively, significantly differently in terms of standardness? The purpose for RQ2 was to follow up on the results for RQ1, which showed that nationality indeed mattered greatly, particularly for the ASG items. Analyses now turn to an explicit comparison of Austrian and German nationals' responses. Specifically, I explored whether and to what extent Austrian and German nationals find their own standard variety or the other standard variety more or less standard. This question is of particular importance for my inquiry because, if the Austrians do indeed rate the ASG words as “standard,” this would provide empirical evidence for an Austrian standard variety and, therefore, the pluricentricity of the German language.

Tables 5 and 6 below display the mean ratings assigned by German and Austrian nationals to ASG and GSG items, respectively, regarding standardness. Results of statistical means comparisons (independent t-tests) between the two national data sets are also given. Independent t-tests pertaining to RQ2 relied on (a) one independent variable (whether a German or an Austrian national), and (b) two dependent variables (a set of Austrian and a set of German Standard German lexical items). Using the Bonferonni Method to account for multiple family-wise comparisons (in this case, two) the alpha level was held to p<.025.

Table 5. Comparison of standardness ratings of ASG items by German and Austrian nationals.

Table 6. Comparison of standardness ratings of GSG itemsby German and Austrian nationals.

Tables 5 and 6 show that, for the ASG items, the Austrians' mean significantly outscored that of the Germans. Conversely, for the GSG items, the German respondents scored a significantly higher mean than the Austrians, although both groups' means are higher than the means for the ASG items. Finally, it appears that the Austrians rated both the ASG and GSG items as “standard,” while the Germans rated only the latter as such.

5. Discussion of the Results.

For the postulation of German as a pluricentric language, the results presented in section 4 reveal an initial empirical basis that extends beyond entries in a dictionary, attestations in the media, or personal views of linguists, that is, the perceptions of Austrian nonlinguist native speakers of German. Moreover, these findings justify, and indicate a need for, further empirical inquiry with more lexical tokens and a larger, more diverse pool of participants.

Let us return to the research questions. First, how much do the rater background variables of nationality, age, mobility, level of education, and experience in linguistics contribute to variation in ratings of written ASG and GSG lexical items, respectively, in terms of standardness? The results presented in section 4.1 show that rater nationality—as determined by which nation, Austria or Germany, the subject reported to have grown up in—matters most in informing their perceptions of the standardness of select ASG and GSG words. Respondent variables such as age, the amount of travel between Austria and Germany, level of education, and experience in linguistics also contribute but to a much lesser degree.

The most prominent finding of the present study is the answer to the second research question, namely, do German and Austrian respondents rate written ASG and GSG lexical items, respectively, significantly differently in terms of standardness? As illustrated in the results given in section 4.2, the answer is yes. More importantly, however, the Austrians do, in fact, perceive the 18 ASG lexical variants as standard when asked to rate them in the context of “when writing a school essay.”Footnote 20 That the Germans regard the ASG items as colloquial or nonstandard, and their own national variants as standard, is expected.

These findings challenge Muhr's (1982:307) suggestion that Austrians generally regard their own national lexical variants as nonstandard:

Bezüglich des Sprachverhaltens der Österreicher wäre weiters noch festzustellen, dass die Österreicher auf ihre Sprache nicht besonders viel halten und sie meistens als minderwertig ansehen. Diese Behauptung entspringt meiner Alltagserfahrung und jener meiner Kol-legen und Bekannten, mit denen ich mich über dieses Problem unterhalten habe.

[Regarding the language behavior of the Austrians, it is further to be noted that the Austrians do not value very highly their language, and that they mostly regard it as inferior. This claim is derived from my daily experiences and those of my colleagues and acquaintances, with whom I have spoken about this problem.]

The results from this study also contradict Martin (2000:109), who writes:

There is a tendency, on the part of both Germans and Austrians, to consider ASG as a variety of lower status than GSG, and in particular to regard Austrianisms as being regional variants (…) rather than national variants.

Both of these conclusions are offered without supporting empirical evidence. The Austrians in this study, contrary to what is suggested in Martin 2000 and Muhr 1982, identified the 18 ASG items as standard.Footnote 21

Furthermore, the results indicate a perceptual duality of standardness for the Austrians: They regarded both the GSG and ASG words on the questionnaire as “standard.” Recall from section 1 that the chief requirement for describing a language as “pluricentric” is the existence of more than one manifestation of standard register in that language. In this sense, one can speak of the Austrians themselves, with their dual standard language ideology, as a de facto representation of German pluricentricity.Footnote 22

Coming back to the original motivation for my research—examining whether, and to what extent, native speakers' perceptions validate the pluricentricity argument—the findings given here do, in fact, provide preliminary support for the argument, but only to the extent that the present study represents an exploratory examination of the matter. An expanded survey, which the findings presented here justify, will allow for a more conclusive measurement of extent.

6. Limitations.

Before ending with a discussion of the conclusions and implications of the present exploratory study, it is necessary to point out the few limitations associated with it. These are primarily methodological, such as the search for a fitting evaluative term for the standardness scale, the presentation of the participants and tokens as representative of larger populations (Austrian or German) and language varieties (that is, ASG or GSG), and the focus on the lexicon and on the written form of language.

The labeling of the standardness scale presented a special problem. This scale was to reveal associations between different lexical items and different registers. Labels 1 and 4 were to represent the top and bottom registers, respectively. Moreover, the labels had to be comprehensible to nonlinguists and evoke comparable, if not identical, meanings in all respondents.

Prior to constructing the questionnaire, I asked ten native speakers from different regions of Germany and Austria which common expressions they would use to describe “the written form of German that is regarded as the most correct” as used, for example, “when composing a school essay.”Footnote 23 The terms they suggested were Hochdeutsch [High German] and Standardsprache [standard language]. I also asked what term they would use to express the opposite of Standardsprache. All informants suggested the term Umgangssprache [colloquial language], and a few respondents additionally mentioned Dialekt [dialect] and Mundart [dialect]. The term Hochdeutsch contains the word deutsch [German] and might, therefore, superficially influence attitudinal responses. I opted for the more neutral-sounding adjective standardsprachlich to label the top of the scale. The adjective umgangssprachlich was chosen to designate the bottom of the scale due to its association with register variation. The alternative adjectives dialektal and mund-artlich could be construed as connoting regional variation and were, therefore, considered inappropriate for this study. In general, subsequent questionnaires would be enhanced by exemplifying and/or paraphrasing the labels standardsprachlich and umgangssprachlich in order to better clarify their semantics to respondents. Footnote 24

Regarding population and token representativity, I would reiterate that the present study is an exploratory investigation, serving, among other purposes, to probe the viability of further research on native speaker perceptions of the Austrian and German standard varieties. I, therefore, worked with a smaller, less diverse participant pool and fewer lexical tokens.Footnote 25 A follow-up investigation targeting a larger, more diverse population and offering more lexical items for evaluation will allow for more conclusive results and, consequently, verify the findings presented here.

Finally, it has been noted that the present study focuses on the written form of the ASG or GSG lexicon. That is, my questionnaire asked respondents to rate words printed on a page. It did not include a listening portion, where participants heard and then rated a set of spoken tokens, or a portion that asked participants to rate various syntactic or grammatical structures. This limitation should not be taken, however, to imply that the Austrian national variety is only a matter of writing, and of words; a number of studies have investigated and convincingly argued for phonological (Moosmüller 1991), morphosyntactic (Tatzenreiter 1988, Muhr 1995), and pragmatic (Muhr 1995) features of ASG.

7. Conclusions and Implications.

This final section serves to situate the present study within a larger context of research, namely, varying individual judgments of the standardness of two national varieties of the German language, an Austrian and a German written standard. Below I recap the motivation for, and central findings of my research in order to answer the following question: What does the present study mean for the field of linguistics, and in particular, for the scholarship on pluricentricity and national varieties?

Recall that the motivation for the present study is not to show, or argue, what ASG is, but rather to offer empirical evidence in support of the pluricentricity argument. As discussed in section 4 above, the conclusion is two-fold. First, the rater's nationality matters most in determining whether the speaker accepts a German or Austrian written standard, or both. Second, Austrians regard both the ASG and GSG items as standard; that is, their elicited perceptions suggest a duality of standardness.

For the scholarship on German pluricentricity, and national varieties in particular, the present study constitutes a new approach to exploring the topics, namely, to use questionnaires to gather empirical data on the perceptions and attitudes of nonlinguists towards these varieties. It is my hope that this new approach will challenge future scholars of socio-linguistics—in particular, those with an interest in empirical research of language use and/or perceptions—to find more precise ways to investigate their topics, and to improve on the methods used here. Moreover, I believe that my preliminary findings justify further, more extensive research on the Austrian national variety in particular. This will involve an empirical component that targets a broader population and includes a larger corpus of tokens for evaluation.Footnote 26 The driving question will be whether, and to what extent, the conclusions offered here are valid.

Finally, my study demonstrates the need of empirical data in testing previous conclusions within the scholarship that are based, for most part, on personal impressions and experience. An example from the present study includes empirical explorations of the arguments in Muhr 1982 and Martin 2000. The results presented here have challenged these arguments. I believe it is important to reexamine claims within the scholarship about the status of, and speaker attitudes toward, language. Language holds considerable significance for identity and culture. It is, therefore, crucial that the scientific sources on the topic reflect actual, existing perceptions of nonlinguist speakers.

APPENDIX

Document 1: Quantitative Questionnaire (Austrians)

Liebe Teilnehmerin, lieber Teilnehmer, Zunächst möchte ich mich sehr herzlich für Ihre Teilnahme an meinem Forschungsprojekt, das Teil meiner Doktorarbeit ist, bedanken. Die Teilnahme erfordert Ihre Beurteilung von 43 Wörtern. Ich schätze, dass das Ausfüllen des Fragebogens höchstens 15 Minuten in Anspruch nehmen wird. Ich möchte Sie darum bitten, Ihre jeweilige Antwort fett zu markieren, das Dokument neu zu speichern, und es als Anhang per Email an mich zu senden. Falls Sie das Dokument ausdrucken und per Hand ausfüllen möchten, können Sie es mir auch per Post zuschicken. Ich werde Ihnen daraufhin das Entgelt erstatten.

Durch das Ausfüllen des Fragebogens bestätigen Sie, dass Sie mit der Teilnahme einverstanden sind. Sollten Sie Fragen zu dieser Umfrage haben, wenden Sie sich bitte an mich (siehe untenstehende Kontaktadresse) oder per Email an ∗∗∗∗

Der institutionelle Kontrollrat für Sozialforschung (SS-IRB, Social and Behavioral Science Institutional Review Board) der Universität von Wisconsin-Madison hat diese Studie genehmigt. Wenn Sie Fragen zu Ihren Rechten als TeilnehmerIn an dieser Studie haben, wenden Sie sich bitte an Dekan Donna Jahnke. Sie ist unter der Nummer ∗∗∗∗ oder per Email unter der folgenden Adresse zu erreichen: ∗∗∗∗

TEIL I. Persönliche Angaben

A) Wo sind Sie aufgewachsen?

0. in München

1. nicht in München, aber in Bayern ∗Name des Wohnorts bitte angeben:

2. in einem Dorf/einer Stadt in Mitteldeutschland. ∗Name des Wohnorts bitte angeben:

3. in einem Dorf/einer Stadt in Norddeutschland. ∗Name des Wohnorts bitte angeben:

4. in Wien

5. nicht in Wien, aber in Ostösterreich ∗Name des Wohnorts bitte angeben:

6. nicht in Ostösterreich, aber in Österreich ∗Name des Wohnorts bitte angeben:

7. an keinem der genannten Orte ∗Name des Wohnorts bitte angeben:

8. an mehreren der genannten Orte ∗Name des Wohnorts bitte angeben:

B) Wie alt sind Sie?

0. 1-19

1. 20-29

2. 30-39

3. 40-49

4. 50-59

5. 60+

C) Wie oft kommen Sie im Durchschnitt nach Deutschland?

0. mehr als ein Mal im Monat

1. mehr als drei Mal im Jahr

2. ein Mal bis drei Mal im Jahr

3. alle zwei oder drei Jahre

4. alle fünf bis zehn Jahre

5. fast nie (d.h. sogar seltener als alle fünf bis zehn Jahre)

6. nie

D) Auf welchem Schultyp haben Sie einen Abschluss gemacht, oder, wenn Sie noch in Ausbildung sind, welchen Schultyp besuchen Sie im Moment?

0. Hauptschule

1. Realgymnasium oder humanistisches Gymnasium

2. Technisches, wirtschaftliches oder anders berufliches Gymnasium

3. Handels- Berufs- oder Hauswirtschaftsschule

4. Uni

5. Keinen der genannten Schultypen ∗Schultyp bitte angeben:

E) Welche Behauptung fasst Ihre Erfahrung mit der Sprachwissenschaft (Linguistik) am besten zusammen:

0. Ich studiere es als Hauptfach oder Nebenfach.

1. Ich habe an der Uni mehr als eine Vorlesung bzw. ein Seminar, das damit zu tun hatte, belegt. ∗Gegebenfalls Namen der Vorlesungen bzw. der Seminare angeben:

2. Ich habe an der Uni eine Vorlesung bzw. ein Seminar, das damit zu tun hatte, belegt. ∗Gegebenfalls Namen der Vorlesung bzw. des Seminars angeben:

3. Ich habe schon einmal in der Schule etwas über das Thema gelernt. ∗Gegebenenfalls Namen des Unterrichtsfaches angeben:

4. Das Thema ist in meinem Unterricht nie durchgenommen worden, aber ich habe schon darüber gelesen bzw. mit anderen darüber diskutiert.

5. Ich habe bisher keine (oder fast keine) unterrichtsbezogene Erfahrung damit gehabt, und das Thema interessiert mich nicht.

6. Ich weiß nicht, was die Sprachwissenschaft (Linguistik) ist.

TEIL II. Umfrage zur Bewertung von Wörtern

a) Beurteilen Sie die folgenden 43 Wörter (#1 bis #43) auf der folgenden Skala von 1 bis 4:

b) Wenn Sie ein Wort nicht kennen, markieren Sie 5 (٫Das Wort ist mir nicht bekannt').

∗Eine Bewertung von ٫3' bedeutet also, dass der Bewertende dieses Wort als ‘Richtung standardsprachlich’ empfindet.

⇒٫standardsprachlich' bedeutet, Sie würden das Wort z.B. in einem Schulaufsatz verwenden, wogegen ein als ٫umgangssprachlich' bezeichnetes Wort bedeutet, Sie würden es nicht in einem Schulaufsatz verwenden