1. Introduction.

Among the most conspicuous developments in linguistics over the past few years have been a renewed interest in a contrastive approach to languages (see, among others, König & Gast 2009) and an increased awareness of third-language acquisition, an area of research with obvious significance from the perspectives of both theory and teaching (see, among others, Cenoz et al. 2001 and Sanz & Lado 2008). While multilingualism is the norm rather than the exception in present-day Europe, substantial research has yet to be carried out on the acquisition of additional, post-L2 foreign languages, especially as far as pronunciation is concerned (Mehlhorn 2007:1745). However, a detailed contrastive study of learners’ second language (henceforth L2) with their third language (L3) may provide insights into what features can be positively transferred from their L2 into the L3. Mehlhorn (2007) argues that learners often concentrate on pronunciation for the first time when learning their first foreign language, and that the awareness of certain pronunciation features raised during L2 acquisition should be used in the classroom during L3 instruction. For instance, if L1 German speakers have learned that glottal stops should be avoided in Russian (their L2), they should be able to use this awareness when learning an L3 which also lacks glottal stops (Mehlhorn, 2007:1747–1748).

Our aim in the present paper is to demonstrate the multifaceted significance of contrastive linguistics with respect to a particular aspect of phonetics, namely, the voicing contrast in Dutch plosives. As shown in section 2 below, the voicing system of Dutch differs from the voicing systems of English and German in a number of ways. Most notably, it lacks aspirated plosives (see, among others, Flege & Eeftink 1987, Lisker & Abramson 1964, Simon 2009). These differences provide the starting point of our study and lead us to formulate research questions with respect to second (and third) language acquisition (see section 2). The remainder of the paper then investigates the manifestation of these differences in the interlanguage of Dutch-speaking learners of English and German, and the implications of our observations for both theory and practice. Our data are derived from an elicitation task in which two groups of participants were asked to read out word lists in all three languages. The method is described in section 3, followed by a discussion of the results in section 4. We finish with a summary and prospects for further research in section 5.

2. The Voicing Contrast in Dutch, German, and English.

2.1. Voicing Languages and Aspirating Languages.

Dutch, English, and German all have a contrast between voiceless plosives (namely, /p, t, k/) and voiced plosives (namely, /b, d/ in all three languages and also /ɡ/ in English and German). The languages differ, however, as to how this contrast is realized phonetically. Whereas word-initial voiceless plosives in English and German are aspirated, they are unaspirated in Dutch. Word-initial voiced plosives in English and German are usually realized without vocal fold vibration and are thus phonetically voiceless.

This is not the case in Dutch, where (phonologically) voiced plosives are produced with PREVOICING, that is, with vocal fold vibration preceding the release of the plosive. Languages that have this contrast between voiceless aspirated and phonetically voiceless plosives are often called ASPIRATING LANGUAGES. Moreover, since the sounds in question differ in terms of energy and lip tension rather than vocal fold vibration, the terms FORTIS and LENIS instead of “voiced” and “voiceless”, respectively, are often used with regard to these languages. Most Germanic languages, including the standard varieties of English and German, belong to this group, as do several Turkic languages (Jansen 2004:41).

Languages that have a contrast between voiceless, unaspirated plosives and phonetically voiced plosives with prevoicing are called VOICING LANGUAGES. Most Romance and Slavic languages, the Baltic languages and Hungarian belong to this group, as do a few Germanic languages or varieties such as Dutch and Afrikaans (Jansen 2004). Table 1 presents a schematic overview of the phonetic realization of plosives in each type of language.

Table 1. Voicing contrast in voicing and aspirating languages.

2.2. The Realization of the Voicing Contrast: Issues and Figures.

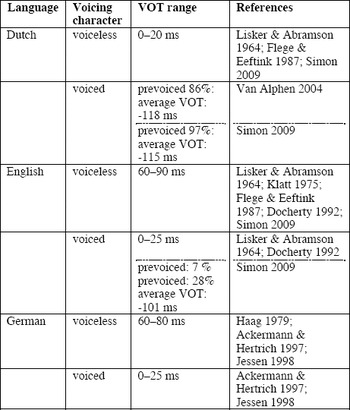

Lisker & Abramson (1964) were the first to categorize languages typologically according to the time that elapses between the release of a plosive and the beginning (the “onset”) of vocal fold vibration required for any subsequent sonorant consonant or vowel. They termed this lag Voice Onset Time (henceforth VOT). Whereas voiceless aspirated plosives are produced with long VOT (hence “long lag” VOT), voiceless unaspirated plosives are realized with “short lag” VOT. Phonologically voiced plosives realized without prevoicing (such as English and German /b, d, ɡ/) also display short lag VOT. Voiced plosives realized with prevoicing have a negative VOT, since the vocal folds start vibrating before the release of the plosive, which is equated with zero (table 2 presents a survey of VOTs in Dutch, English and German, with references). Given that stimuli and speakers differed between the studies in question, the third column only gives a rough indication of the range of VOT obtained across the three languages.

As table 2 shows, the voicing contrast in plosives is realized very differently in Dutch compared with English and German. Whereas voice-less plosives have a long VOT between 60 and 90 ms in English and German, VOT in Dutch is in the short-lag range, roughly between 0 and 25 ms. Voiced plosives in Dutch are usually realized with a negative VOT between -120 and -110 ms. Van Alphen (2004) conducted a perception experiment, in which participants were asked to identify initial plosives with or without prevoicing. The results of the experiment revealed that almost all tokens realized with prevoicing were identified as matched by the participants. By contrast, the participants identified the majority of tokens without prevoicing as voiceless, suggesting (also in contrast to Nooteboom 1974) that prevoicing is an important perceptual cue to the voice character of Dutch plosives.

In aspirating languages, there is often a certain amount of variation with respect to the realization of word-initial /b, d, ɡ/. Whereas some speakers produce prevoicing, the majority of native speakers of English and German realize word-initial plosives in the short-lag range, with VOTs between 0 and 25 ms. The differences in the VOT values in voiced and voiceless plosives in Dutch, on the one hand, and English and German, on the other hand, have consequences for L2 acquisition. L1 speakers of Dutch acquiring English and/or German as an L2 need to realize the familiar phonological contrast between voiceless and voiced plosives differently at the phonetic level when speaking these two foreign languages.Footnote 1

Table 2. VOT values in Dutch, English, and German.

2.3. Research Questions.

The present study addresses two main research questions. First, how do L1 speakers of Dutch realize the voicing contrast in their German “interlanguage” (that is, L2 system)? In other words, to what extent do they learn to produce voiceless plosives with longer VOTs (and hence to aspirate them) and voiced plosives without prevoicing? Simon (2009) studied the voice contrast in the L2 English interlanguage of L1 Dutch speakers with a high proficiency in English and found that these advanced learners had learnt to produce aspiration in English (that is, realized voiceless plosives with long-lag VOT), but they transferred prevoiced plosives from Dutch into English. These participants’ English interlanguage thus displayed a mixed system contrasting the prevoiced plosives of a voicing language (Dutch) with the aspirated plosives of an aspirating language (English).

Two factors were suggested as an explanation for this mixed system: the greater acoustic salience of aspiration compared with prevoicing, and the fact that the participants had been participating in a pronunciation course that included explicit instruction on the production of aspiration but not on the lack of prevoicing in English. In our present study, we aim to investigate which type of system is found in the L2 German of L1 Dutch speakers who learned German as their second foreign language after English. Studies in L3 acquisition (see Jessner 2006) have shown that both the L1 and the L2 may influence any subsequent L3 acquisition. One might expect participants who are learning German as L3 to transfer their L1 Dutch system to German, that is, to produce voiceless plosives with short-lag VOT and voiced plosives with prevoicing. However, it is equally plausible that participants have a single system in both foreign languages and hence use a mixed system in German, too, with prevoiced and aspirated plosives.

The second research question in the present investigation is related to the effects of pronunciation instruction: to what extent does a pronunciation course influence the realization of a fine-tuned phonetic phenomenon like VOT? Earlier studies have shown that focused phonetic training can improve perception and production of non-native contrasts considerably. For instance, Reis et al. (2008) found that perception training for eleven L1 speakers of Brazilian Portuguese (a voicing language, just like Dutch) had a positive effect on both perception and production of the voice contrast in English. Bradlow et al. (1996) and Hattori & Iverson (2008) investigated the acquisition of the contrast between /r/ and /l/ in English by L1 speakers of Japanese and also found that a series of phonetic training sessions positively influenced their participants’ production of voice contrast.

In the present study, we aim to examine the effects of a general pronunciation course, rather than focused phonetic training, on the production of fine phonetic differences between the L1 and the L2 or L3. We investigate these differences by comparing the performance of two groups of L1 Dutch speakers in an elicitation task. One group had been studying English and German at an advanced level and had participated in a general pronunciation course in both foreign languages. The other group had been studying both languages to a much lesser extent beyond A-levels (high-school) and had not been given any explicit pronunciation instruction in either language.

3. Method.

3.1. Participants.

There were two groups of participants in this study. Each group consisted of ten second-year-students attending two different post-secondary Dutch-speaking institutions in Flanders. They were native speakers of Dutch, aged between 18 and 27 (median: 19). All participants started studying the foreign languages in secondary school, in the same order: first English, then German.Footnote 2 The participants were also balanced for gender, with half of the participants male and the other half female in each group.Footnote 3

The first group of participants (henceforth called the “trained” group) had been studying English and German towards a Bachelor of Arts degree in Applied Linguistics. This group had received thorough practical training in both foreign languages as well as in their L1, Dutch. As part of formal pronunciation training, the term “aspiration” had been explained to them, and they practiced aspiration in English and German. By contrast, the students’ attention had not been explicitly drawn to the absence of prevoicing in English, and the term “prevoicing” had not been used in the pronunciation classes.

The other, “untrained” group had been pursuing a Bachelor of Arts degree in Journalism. Although this degree requires English and German as foreign languages, languages are altogether marginal in the study program, and no formal pronunciation training is provided.

In order to assure the homogeneity of the groups in terms of participants’ linguistic background and meta-linguistic competence, we devised a questionnaire to enquire about participants’ knowledge of languages, their contacts with the foreign languages in question, their phonetic training, and so on. Participants were also asked whether they could define the phenomenon of aspiration. The answers to this question revealed that, out of the ten students in the “trained” group, nine were able to define the term “aspiration” more or less precisely, whereas no-one in the “untrained” was able to do so (see also 5.2.)

In addition to these non-native participants, we put together a control group consisting of native speakers of German in order to complement the results of earlier studies on VOT in German. Although we did use previously published studies on VOT as our main points of reference (see table 2), ten L1 speakers of German were recorded while carrying out the same reading task as the non-native participants.Footnote 4

3.2. Stimuli.

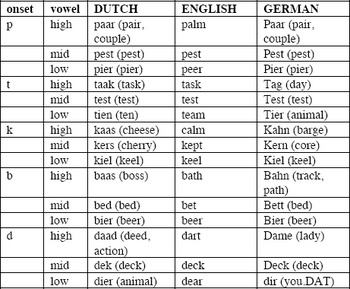

The target stimuli consisted of 15 existing words in Dutch, English, and German. All stimuli were monosyllabic and had a CV(C)C structure, with the sole exception of bisyllabic German Dame ‘lady’ (there being no German /d/V(C)C words, in which the V is a long /a:/).Footnote 5 Stimuli were controlled for place of articulation (bilabial and alveolar) of the onset consonant and height of the subsequent vowel. The voiced velar plosive [ɡ] was not included because it does not occur as a phoneme in Dutch (except in loan words in certain varieties). Each reading list (in each of the three languages) thus consisted of 15 monosyllabic targets with five different plosives in the onset, namely, voiceless [p, t, k] and voiced [b, d], followed by a low, mid, and high vowel. Table 3 lists the selected target stimuli from each language by onset consonant and vowel height.

Table 3. Target stimuli.

In addition to the 15 targets per language, five false stimuli were selected in order to distract the participants’ attention from the purpose of the reading task. The distractions were CV(C)C words with a fricative or sonorant consonant in the onset rather than a plosive. Examples are moed ‘courage’, Mond ‘moon’, moon and lief ‘sweet, nice’, lieb ‘sweet, nice’, leaf. The complete lists of 20 stimuli were then randomized per language so as to assure that no patterns could be discerned. In this way we obtained three lists of the same 20 stimuli per language, each time in a different order.

3.3. Procedure.

The participants first performed the reading tasks in their native language (Dutch, L1), then in their first foreign language (English, L2) and finally in their second foreign language (German, L3). The stimuli were presented to the participants on a laptop computer screen as Power Point slides. They were asked to read the words aloud at a comfortable pace. The microphone was placed on a stand a few centimeters from their mouths, and the sound files were saved on the computer. The participants were not informed about the specific aim of the study, so that they would not pay special attention to the production of the initial plosives.

Each interview consisted of two parts for each language. After some brief initial instructions, the participants were asked to read out a short text in the language of the following reading task so as to activate the language in question and put the participants in “monolingual” rather than “bilingual” mode (Johnson & Wilson 2002). The text selected for this purpose (a brief essay on semiotics) was originally in German, translated into English and Dutch for the purpose of our study. Then the word lists were presented with one word appearing on a slide, with a new word appearing every three seconds. In this way, each participant was successively shown one text and three word lists of 20 stimuli. (The L1 German control group was only asked to read the word lists for their L1.) Each interview was initially conducted in Dutch, with the interviewer switching to English and then German in due course.Footnote 6 After the interviews, the participants were asked to fill in the questionnaire and sign a consent form regarding the use of their recordings for scientific purposes.

Following the interviews, the VOT of each plosive was analyzed by means of the speech analysis package Praat (Boersma & Weenink 2008), that is, the VOT was measured per stimulus and entered into an Excel file. The measurements were carried out by two phonetically trained native speakers of Dutch, who had excellent command of both English and German. Prevoicing was measured from the moment when vocal fold vibration became visible in the oscillogram and/or in the spectrogram, up to the release phase of the plosive. Positive VOTs were measured from the release of intra-oral air for the production of the plosive up to the beginning of vocal fold vibration for the subsequent vowel, as seen in the oscillogram or the spectrogram when the second formant appeared.

4. Results.

4.1. Voiceless Plosives.

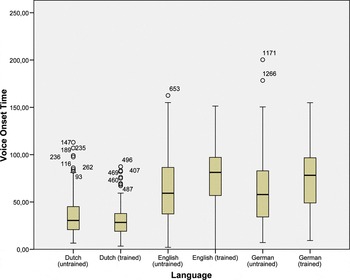

Figure 1 shows the VOT values of the voiceless plosives as produced in Dutch, English, and German by two groups of participants—the trained group and the untrained group.Footnote 7 A Friedman test (the non-parametric alternative to a one-way repeated measures ANOVA) reveals a significant difference in VOT in all three languages (L1 Dutch, L2 English, L3 German), both for the untrained participants (χ2 (2, n=269)=193,435, p<.005) and for the trained participants (χ2 (2, n =257)=314.45, p<.005).

Figure 1. Boxplots of VOT values for voiceless plosives.

The median values reveal a considerable difference in VOT between Dutch on the one hand and English and German on the other (see table 4).

Table 4. Median VOT values for voiceless plosives (in ms).

At first sight, the median values of English and German in table 4 appear to be quite similar. However, post-hoc Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests reveal that the difference in VOT between English and German, though small (r=.1) by Cohen's (1988) criteria (.1=small effect, .3=medium effect, .5=large effect), is in fact statistically significant for the untrained participants (z=-2.022, p=.043<.05). The difference between English and German VOT values for trained participants, by contrast, is not significant (z=-1.754, p=.079>.05). The trained participants’ median value for German (78.2 ms) is almost the same as the German control group's median VOT, which is 77.1 ms.

Comparing trained with untrained participants, we see that the trained participants produced higher VOT values in both English and German. In English, the median VOT value in the trained group is 22.1 ms higher than in the untrained group, while in German, the difference is 20.3 ms. As expected, the median values for Dutch are similar in both groups (30.5 ms in the untrained and 28.4 ms in the trained group). Mann-Whitney U tests reveal that the difference in VOT values between trained and untrained participants is significant in English (U=26242, z=-5.272, p<.001) and in German (U=27218, z=-4.910, p<.001).Footnote 8

4.2. Voiced Plosives.

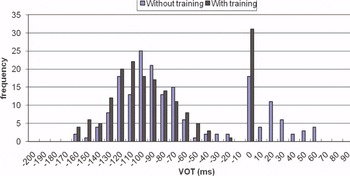

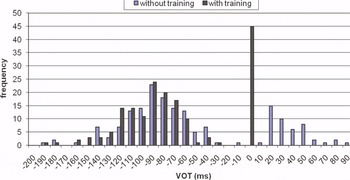

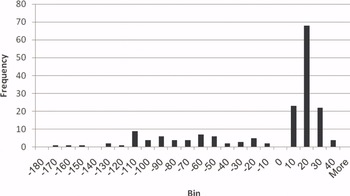

Results for the voiced plosives are given per language in the histograms in figures 2 to 4. These figures reveal that the VOT values for voiced plosives show a bimodal distribution in all three languages: whereas some plosives are produced with prevoicing (with VOT values roughly between -190 and ‑10), others are in the short-lag VOT region, with a peak between 0 and 10 ms. The histograms therefore look similar in the three languages and different from the values recorded by the native-speaker control groups in English and German. Figure 5 is a histogram with the VOT values of four L1 speakers of German.

Figure 2. Histogram of VOT values in voiced plosives in L1 Dutch.

Figure 3. Histogram of VOT values in voiced plosives in L2 English.

Figure 4. Histogram of VOT values in voiced plosives in L3 German.

Figure 5. Histogram of VOT values of voiced plosives in L1 German.

Although the L1 German speakers produced a number of tokens with prevoicing, the majority of their plosives (117 out of 175 tokens, that is, 66.9%) were within the “short-lag” VOT region.

We now compare the percentage of prevoiced tokens produced by the trained and untrained participants in the three languages. Table 5 presents the proportion of prevoiced plosives in Dutch, English, and German by the two groups.

Table 5. Frequency of prevoiced tokens in L1 Dutch, L2 English, and L3 German.

Whereas Friedman tests revealed significant differences in VOT values between the three languages, both in the untrained group (χ2 (2, n=173)= 35.496, p=.001) and in the trained group (χ2 (2, n=169)=12.744, p=.002 <.005), table 5 shows that the percentage of plosives produced with negative VOT is very similar in all three languages. The results of non-directional z-tests (with a critical value of 1.96 for a 5% significance level) revealed that the differences between the untrained and the trained group did not reach significance (Dutch: z=1.748<1.96, English: z= 0.692<1.96, German: z=0.212<1.96). In other words, trained and untrained participants did not significantly differ in the extent to which they produced prevoicing in any of the three languages under investigation.

5. Discussion.

5.1. The Voicing Contrast in the Two Interlanguages.

The results for voiceless and voiced plosives showed that the L1 Dutch participants have a mixed system in German, with prevoiced /b, d/ and aspirated /p, t/. The voicing contrast in the German interlanguage of these participants (whether trained or untrained) is, thus, roughly the same as the voicing contrast in their English interlanguage. This is consistent with the findings of Simon 2009 for L2 English.

The question of how the mixed German system emerged is an interesting one. On the one hand, it may have arisen as a result of a transfer of prevoiced plosives from the learners’ native language, Dutch, into German, and the successful acquisition of German aspirated plosives. In that case, the participants may have been helped by the fact that they were familiar with aspirated, voiceless plosives, because they had previously learned English. Alternatively, participants may have transferred their entire L2 English system (different as it is from the English “target” system) to their L3, German. This interpretation is supported by the fact that the untrained participants, who have generally had little contact with spoken German, also aspirated voiceless plosives in German. This suggests positive transfer of aspiration from English, a language with which they come into much more close contact via the media.Footnote 9

Our results are consistent with the results of a study by Llama et al. (2007) on the production of VOT by two groups of L3 Spanish learners. One group had English as their L1 and French as their L2, while the other group had French as their L1 and English as their L2. For the L1 English group, both the L2 and the L3 had the same type of laryngeal contrast, that is, both French and Spanish are voicing languages which lack aspiration. Llama et al. (2007) found that these learners’ VOT production of voiceless stops was remarkably similar in their L2 and L3: While they aspirated more than 60% of the voiceless stops in both French and Spanish, they adjusted their VOTs in the direction of the target short-lag values. The authors, therefore, hypothesized that learners resorted to their L2 for the production of their L3. Since both French and Spanish lack aspiration, reduced VOTs in Spanish may be the result of positive transfer from the learners’ L2.

The second group of participants (L1 French speakers), however, provided the crucial piece of evidence for the authors’ hypothesis. For these participants, the laryngeal system in their L2 (English, an aspirating language) is different from that in their L3 (Spanish, a voicing language). Even though the target realizations of English and Spanish are different, the participants produced strikingly similar VOTs in both of their foreign languages. The authors, therefore, argue that “it is reasonable to consider that Group A [that is, L1 English speakers] also resorted to the L2 as a result of an L2 status effect and not because of the typological relationship between the L2 and L3” (Llama et al. 2008:321).

Since the L2 and L3 of the learners in the present study have the same laryngeal contrast, our results cannot provide decisive evidence for this hypothesis. However, the participants showed signs of the same mixed laryngeal system (containing prevoiced and long-lag stops) in their L2 (English) and their L3 (German), and our results are in line with the claim in Llama et al. 2008 that L2 transfer plays an important role in L3 acquisition. Since both Llama et al. 2008 and our own study deal with L3 acquisition of VOT, further research will be needed to investigate whether other features also tend to be transferred from the L2 to the L3.

5.2. Effects of Instruction.

The results revealed that the trained participants produced voiceless plosives with longer VOTs in both English and German than the untrained participants. This seems to suggest that general pronunciation training facilitates the acquisition of aspiration and is, therefore, indeed useful. At the same time, two provisos are in order.

First, we should not automatically assume that pronunciation training causes the longer VOTs produced by the trained participants. Factors such as the learner's motivation and aptitude are known to influence the L2 acquisition process (see, for instance, Major 2001 for an overview). Thus, it is possible that the higher motivation and greater aptitude of students who undertake the study of languages at a high level is partially responsible for the longer VOTs produced by the trained group (with or without focused pronunciation training). After all, a language-based degree course tends to attract students who are more motivated to master the pronunciation of a foreign language, and are more gifted in this respect. Moreover, nine out of the ten trained participants were able to define the term “aspiration”, demonstrating a metalinguistic understanding of this process, which distinguishes them from the untrained participants. The extent to which the production of aspiration is a consequence of this metalinguistic insight or of practical exercises (that is, implicit instruction) is an open question. While explicit instruction in English and German clearly contributes to the differences observed in the realization of voiceless plosives by both groups, it is likely not to be the only factor. In order to reduce the potential effect of differences in motivation and aptitude between speaker groups, future studies could use participants with similar educational backgrounds and incorporate the training sessions into the study.

The second proviso is that the untrained participants, too, produce significantly longer VOTs in voiceless plosives in English and German than in Dutch. In other words, the untrained participants also tended to aspirate. This confirms the hypothesis that aspiration is acoustically salient, and that the contrast between the unaspirated plosives of Dutch and the aspirated plosives of English and German is perceived and imitated even by untrained participants. Even without explicit training, L1 Dutch speakers seem to be able to learn aspiration in English and German. Note that English and German both have voiceless stops that have easily identifiable counterparts in the learners’ L1, Dutch. Therefore, these voiceless stops are classified as “similar” L2 phones (Flege 1987). In this light, this result may be surprising, as it has been demonstrated that learners tend to have difficulty with establishing new categories for or learning the articulations of similar phones. However, the fact remains that even our untrained participants were able to master the production of aspiration to some extent. Further research is clearly needed, for example, into the potential effects of naturalistic English input in everyday life. It is possible that this naturalistic input, provided to the learners through English media (such as films, which are subtitled rather than dubbed in Flanders), is sufficient for them to learn how to produce aspirated sounds, after all.

On the other hand, both groups realized voiced plosives with prevoicing, and thus in a non-target-like manner. This confirms the observation in Simon 2009 that it is hard to unlearn prevoicing. When speaking an aspirating language, L1 speakers of a voicing language will have difficulty producing voiced plosives in the “short-lag” region (see Simon 2010 on how early L2 acquisition differs). In addition, it should be kept in mind that, although the trained participants had been instructed on the production of aspiration in English voiceless stops, they had not received explicit instruction on the absence of prevoicing in English voiced stops. This asymmetry could be eliminated in future research by examining the stops produced by learners who had been trained on aspiration as well as prevoicing. These learners’ performance could then be compared with that of learners who had not received instruction on either aspiration or prevoicing.

6. Conclusion.

This study has shown that both trained and untrained participants transferred prevoicing from Dutch into English and German but acquired aspiration. Thus, they showed a “mixed” laryngeal system in both their L2 and their L3. Pronunciation training proved to have only a moderate effect, since even untrained participants produced voiceless stops in the target Voice Onset Time range.

An interesting perspective for further research could be historical. As far as the influence of language contact on the voicing system of Dutch and other (West) Germanic languages is concerned, the field of research is still wide open. Simon (to appear), for instance, links present-day acquisition studies to historical accounts of language contact between voicing and aspirating languages (see also Iverson & Salmons 2008), and presents two alternative hypotheses on the origin of the laryngeal systems in Germanic voicing languages. These hypotheses are based on two different types of transfer from a source language into a recipient language, which Van Coetsem (2008) termed “imposition” and “borrowing.” These types of transfer differ in whether the source or the recipient language speaker is the agent. Imposition occurs when the source language speaker is the agent, who transfers elements from the source language into the recipient language. According to one hypothesis, the Dutch voicing system emerged as the result of imposition from a Romance or Slavic language onto a Germanic language, that is, speakers of a Romance or Slavic language started to speak a Germanic language, but imposed their Romance/Slavic voice system onto the Germanic language. Borrowing, by contrast, takes place when the recipient language speaker is the agent, who transfers elements from the source language when using the recipient language. According to a second hypothesis, the Dutch voicing system is the result of borrowing from a Romance or Slavic language: Germanic speakers became bilingual with the Romance language and borrowed the voice system of the Romance language when speaking the Germanic language. Contrastive studies like ours can provide significant synchronic data for this kind of undertaking. The inclusion of other, non-Germanic languages is the next logical step.