1. Introduction.

The long-standing debate in historical English studies concerning the origins and development of the Modern English (ModE) progressive has to do largely with the fact that it has two putative sources. The first is the Old English (OE) construction built of the copular verb beon (or wesan) and the present active participle (pap). I refer to this as the beon + pap construction, an example of which is given in 1.1

As I discuss below, the OE syntagm in 1 is not really one construction but several different ones sharing the same syntactic form.

The other probable source is a locative construction, attested from Middle English (ME), made up of the copular verb, a locative preposition (usually on) and a substantivized form of the verb. I refer to this as the locative construction, an example of which is given in 2.2

While this paper focuses on preposition on + -ing (substantivizing suffix), it should be mentioned that other types of locative constructions are not unknown, including the use of prepositions such as in or at (Jespersen 1949) or substantive forms with locative prepositions of the OE on huntoþe type.

While formally these two constructions were distinct from one another (and from the ModE progressive), certain changes made them identical in the development of English. First, beginning at the end of Old English and continuing throughout Middle English, the older participial suffix -ende was replaced by -ing, a suffix that had derived abstract feminine nouns in Old English; for some varieties of English, this replacement was complete by the end of the ME period (see, for example, Lass 1992:145–146). Second, within the locative construction, steady phonological attrition of the prepositional element reduced it to an unstressed prefixal vowel, which was eventually lost by aphesis (Jespersen 1949). These changes are summarized in 3.

Some have argued that the progressive can be traced directly to beon + PAP in 1 (Curme 1913, Goedshe 1932, Mitchell 1985, Mossé 1938, Nickel 1966, Scheffer 1975), while fewer have linked the progressive directly or exclusively to the locative construction (Braaten 1967, Dal 1952, Jespersen 1949:168—although as Jespersen explains here, he changed his view over the years). In my view, the dispute is the result of scholars having attended too much either to form or to meaning in their reconstruction. Specifically, those who argue that the progressive developed from beon + PAP tend to focus primarily on the formal identity between the OE construction and the progressive, while those who posit a more direct development from the locative construction chiefly invoke semantics in support of that putative link.

My purpose in writing this paper is to present aspects of a refined theory of the development of the progressive in the history of English, providing a plausible reconstruction from both semantic and formal perspectives. I argue that a direct continuation from OE beon + PAP to the present-day English progressive is highly problematic from a semantic point of view. To build that argument, I give evidence of the broad semantic distribution of OE beon + PAP and then consider its putative semantic link to the progressive in light of current studies on the grammaticization of verbal aspect. As I show, such studies provide strong indication against a direct diachronic relationship between the two. However, as I also present here, the same studies are wholly consonant with a provenance of the progressive from the locative construction. Nevertheless, as scholars have known for a long time, textual evidence for the relationship between the progressive and the locative construction is slight given that the locative forms appear so rarely in historical texts. Therefore, in order to strengthen the plausibility of that link, I show how Early Modern English grammarians actively proscribed the locative construction and thus encouraged the aphesis outlined in 3 above. The investigation into the position of Early Modern English grammarians allows us to understand more clearly a few of the most difficult aspects of the history of the progressive: (i) why the beon + PAP construction appears to have continuous attestation throughout the history of English; (ii) why the locative forms occur so rarely in English texts; and (iii) how progressive meaning came to be so sharply defined in the copula + PAP form in the Early ModEng period.

2. OE beon + PAP and Its Status as a Source of the Progressive.

Nickel (1966), in his support of a direct provenance of the English progressive from the OE beon + PAP construction, claims that it had a clearly defined function in the OE verbal system, a claim I think rightly refuted as “exaggerated” by Mitchell (1976:277). In fact, beon + PAP is notoriously unsystematic in Old English, especially from a semantic point of view, and it is this semantic unsystematicity that makes it such an unlikely source for progressive meaning. The erratic semantic range of beon + PAP is due at least in part to the fact that it does not represent a single underlying construction. Sometimes it—along with syntactically similar constructions—is autochthonous, as listed in Nickel 1966:270ff. (see also Denison 1993):

At other times, however, it is invoked as a calque for certain verbal constructions in the struggle to maintain harmony in form and meaning between Old English and Latin. The tension between form and meaning is evident in Ælfric's Preface to Genesis (see Robinson 1973:469):

[…] and we durron na mare awritan on Englisc þonne þæt þæt Læaden hæfþ, ne þa endebirdnisse awendan buton þam anum þæt þæt Læden and þæt Englisc nabbaþ na ane wisan on þære spræce fadunge.

‘and we dare no more write in English than that which the Latin has, nor change the order except in the one instance that the Latin and the English do not have the same way in the speech order.”

(Mitchell & Robinson 1992:194, my translation)

Thus when possible, a translator was obliged to keep the Latin endebirdnisse ‘order’ in Old English and beon + PAP became well established in literary traditions as a means of preserving the form-meaning balance in certain contexts.

One such context, and one that is especially illustrative, is that of glossing, as in the Vespasian Psalter (VP) (Sweet 1966), where Anglo-Saxon scribes annotated the text by writing the OE forms directly above the Latin.3

In this paper, I present data from glosses because here the relationship between Latin and OE forms is perhaps the clearest. Obviously, the further one goes from the tight syntactic relationships evident in glosses into other translation contexts, the more difficult it is to assert why any instance of beon + PAP is being used. A typology of the Latinate beon + PAP reflex in Old English is beyond the scope of this paper.

In the Vespasian Psalter, for example, beon + PAP is a calque for the periphrastic forms of Latin deponent verbs, which carried passive mor-phosyntax but had active meaning. In the perfect system, such deponents were periphrastic, made up of the copula + past participle. This construction would normally express passive meaning for most verbs in Latin, and in those cases where it does, the glossator follows the same syntactic periphrasis for Old English, thus achieving formal and semantic harmony.

Again, it is important to recall that in the case of deponents, the form appeared passive but its meaning was active. This tension is resolved consistently in the Vespasian Psalter by glossing the perfect periphrasis of deponents with beon + PAP. In other words, the Latin past participle of the deponent, which was active in meaning, is rendered by the PAP in Old English, an example of which is given in 5.4

This treatment of Latin deponents is not limited to English; similar examples are found in other Germanic languages, as in the example of copula + PAP in the Old High German Isidor (cited in Grimm 1898:5).

See also below for more on the cross-Germanic similarities of the OE situation.

Here the OE calque clearly indicates the concentration on form over meaning. Note that in 5 the copula is in the present in both Latin and Old English. The Latin present copula + past participle, both in the passive and deponent uses, signaled a perfective or past meaning, and so the use of the present copula in Old English is an imitation of the Latin form. However, in such contexts in the Vespasian Psalter, the OE auxiliary occurs only about half of the time with the present of beon and the other half with the past, as in 6.

In cases such as 6, the glossator is likely attempting to capture not only the form of the periphrastic deponent, but also something of its past time semantics. The variable use of the present and past copula in the OE gloss underscores the struggle as to whether form or meaning was more important.

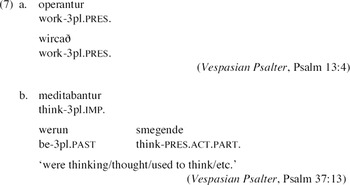

Another aspect of beon + PAP in glossing that illustrates its unsystematic use is its variable employment among deponent verbs. While the perfect periphrases of deponents are always calqued with beon + PAP, synthetic deponent forms are variably treated, sometimes rendered with a synthetic OE form, as in 7a, and sometimes with beon + PAP, as in 7b.

Although, as I discuss below, there is an association between imperfectivity and beon + PAP, that association does not seem to be the only motivation for its use in the Vespasian Psalter. In other places in the text, beon + PAP appears for other synthetic deponent tense/aspect forms, as for instance in VP 34:27 where bið smegende ‘were thinking’ glosses the Latin deponent future meditabitur ‘will think’. In this case, the futurity of the Latin synthetic form is captured with bið, but the periphrasis is likely due to its association with Latin deponency since no nondeponent Latin futures are glossed with beon + PAP in the Vespasian Psalter.

Given that periphrastic deponents are consistently treated with beon + PAP and that synthetic deponents are variably treated, one might be tempted to infer a growing association with deponency more generally (Scheffer 1975, Wülfing 1901, among others). However, such a relationship never obtains categorical status in Old English (see also Jespersen 1949:166). In fact, beon + PAP is not an obligatory reflex for any Latin construction in OE writing.

Thus, Mitchell (1985) is dismissive of the Latin connection since he finds instances of beon + PAP that do not appear in translation, and, according to him, most of the relevant Latin constructions that could be translated as beon + PAP are not. However, these objections, even if true, do not preclude Latin influence since the relationship between Latin and Old English was dialectic and therefore a categorical relationship between specific forms in the two languages is not expected.6

However, it may be that the Latinate construction became confused with some of the autochthonous constructions listed in 4, although the confusion would have been largely formal since it is generally agreed that such autochthonous constructions were not verbal (Mitchell 1976, Traugott 1992). Conversely, it is clear that certain instances of Latinate beon + PAP were verbal, as shown by substitutions in which do replaces both the auxiliary beon and the PAP. This is presumably possible because both the auxiliary and the PAP make up the VP (see also Traugott 1992 and Visser 1963):

Evidence of confusion between the nomen agentis form and the participle comes from cases where the same passage translated from Latin appears alternately with participial -ende and the nominal -end in variant manuscripts. Apparently, this confusion increases toward the close of the OE period (Nickel 1966:3–4). For the account developed here, the autochthonous - allochthonous debate is largely irrelevant since neither source is a suitable candidate for later progressive meaning. However, even if there is confusion, I think we are best to consider it a literary confusion since it is difficult to accept a scenario in which a foreign literary form would have influenced the spoken language at a time when most speakers were not literate.

I believe that the dismissal of allochthonous influence in these literary texts is a reflection of what Stein (2005:197) refers to as “the present mainstream stance […] to give default preference to endogenous explanations.”

By “relevant historical construction,” I mean any syntagm of the copula + PAP formula, including the related -end nominal constructions. For Middle English, copula + PAP in -ing are included, although a few -end(e)/-and participles continue into later English as indicated earlier.

In terms of distribution across genre, it is historical and religious texts, areas that were especially affected by Latin models, that show the greatest numbers of beon + PAP tokens. It is to be noted that the genre of history here is represented largely by Bede's Ecclesiastical History and so it too can be considered as having been influenced by Latin and the practices of religious writing/translation. Thus, the data in table 1 support the position that beon + PAP had become associated with certain types of writing, particularly those constructed in the religious context of a Latinate literacy (Rigg 1996:72). Of course, formal imitation, particularly in the translation of religious texts, is a phenomenon not limited to Old English (see Platter & White 1926 on the imitative nature of Latin syntax based on Greek religious models), and such imitation can sustain highly foreign constructions for a very long time. For instance, even into modern times the performance of religiosity often involves use of archaic or even non-English forms in spontaneous prayer based on knowledge of Early ModEng translations of the bible, such as we beseech unto thee (see, for instance, Joseph 1987:71).

As the variable employment of beon + PAP in the Vespasian Psalter suggested, the periphrasis was not semantically fixed in Old English, and since its use was arguably more a matter of Latinate writing convention, its grammatical domain was not well circumscribed. Certainly it was not limited to progressive aspect (Traugott 1972, 1992); it appeared in several aspectual contexts, although it tended to fall mostly under general imperfectivity (Scheffer 1975), which is a situation viewed as unbounded in that it can be progressive, iterative, habitual, gnomic, etc. (Comrie 1976, Bybee et al. 1994).9

Progressive: situation is on-going at reference time

Iterative: action is repeated on at least one occasion

Habitual: situation is customary or repeated on several occasions

Gnomic: same as habitual but predicated of nonreferential or generic subjects Studies have also shown that these sub-meanings of imperfectivity are diachronically prior to it in so far as imperfective forms grow out of these more specific meanings (Bybee et al. 1994, Bybee & Dahl 1989, Comrie 1976, and see below).

Old English did not have obligatory categories for any of these more specific imperfective expressions. Instead, the simple tenses covered both perfective and imperfective domains, although more specific aspects within the domain of perfectivity were emerging in the habban/beon + past participle periphrasis (Carey 1994, Smith 2001).

The data in table 2, taken from the same database discussed above (the texts for which are given in the appendix), show the diachronic perseverance of the semantic overlap exemplified in 8. In that database, each of the forms was coded for aspectual meaning as perfective, habitual, progressive, iterative, etc. Tokens were considered to encode progressive meaning when they indicated actions that are on-going at a specific reference time (see, for example, Comrie 1976), sometimes, but not always, with an accompanying adverbial.

Thus, an instance like that in 9 was coded as progressive since seocende and smeagende report on activities that occur during the time the subject, ic, was at the church, which was a point in the past. Note too that the activities of seocende and smeagende are unbounded; we do not know when they begin or end, only that they were on-going at the point established in the past.

Beon + PAP in 10, however, was not coded as progressive since in this case the action of the verb ehtende is understood to have been one describing an action that began and ended several times over an extended period, not on-going at a specific point in the narration (see also Klaeber 1950:134). In other words, it is read as iterative and was so coded.12

In a sample of five ModE translations, I found that wæs ehtende is never treated as a progressive (Alexander 2001, Donaldson 2002, Hieatt 1967, Liuzza 2000). In one, it is rendered with an adverbial -ing participle (Sullivan & Murphy 2004). Whether one accepts the specific iterative meaning or not, I think the non-progressive/other imperfective reading is clear enough and certainly supported by the treatment in translation.

By separating the tokens into two groups, progressive and other imperfective (the few perfective instances are excluded in table 2), we see that progressive meaning does not become robustly associated with beon + PAP until the Early ModE period, although after the OE period it is more correct to speak of copula + PAP, since it may well be that some of the instances are aphetic locatives, that is, the locative construction after the loss of the initial locative element. From 1500 onward, progressive meaning becomes fixed within the form while other imperfective meanings dwindle.

Since imperfectivity in Old English was generally expressed through the simple present and past, table 2 shows that there was overlap in the semantic domains of the simple tenses and beon + PAP in Old English (see also Traugott 1992 and the discussion of glossing above). I have suggested that the overlap is due to the fact that verbal uses of beon + PAP (see again note 6) entered into the language via Latinity and a literacy based on Latin models, although again certain uses may well have been confused with morphosyntactically similar native constructions involving a PAP or a formally related nominal in -end. Furthermore, there is no evidence that the construction as a whole was becoming more systematic in Old English or even into Middle English (Fischer 1992).

Thus, the introduction and continued use of a verbal beon + PAP is not unlike the situation in Dutch where the uses of a copula + PAP construction entered into the literary language, probably based also on Latin models, and is still used in modern times.13

The continuation of a literary copula + PAP and its relationship to Latin in Middle English is discussed in Mustanoja 1960:585. As Mustanoja points out, the practice of translating Latin constructions with copula + PAP was much less common in the ME period, which is reflected in the overall diminished frequency of the form from Old to Middle English.

3. Development of Progressive Meaning and OE beon + PAP.

The semantically broad use of OE beon + PAP (and its continued ME uses), whether they were autochthonous or borrowed or both, is the greatest problem with linking them to the ModE progressive, which occurs in a much more limited semantic space within the imperfective domain. Because of the formal confusion between autochthonous and allochthonous instances of beon + PAP and between the continued ME reflexes of beon + PAP and the locative construction with a weakened or elided prepositional element, English internal data are exceedingly vague as to the development of the progressive. For this reason, I suggest that taking a step back, so to speak, and looking at the way progressive meaning develops in the languages of the world can shed light on this most frustrating of philological problems.

Grammaticization, defined as the study of the development of grammatical material in language, was a major preoccupation of 19th and early 20th century linguists and philologists. However, with the heavy focus on synchrony in American structuralism and generative schools, grammaticization did not receive much attention again until the 1980s (although see Benveniste 1966, Kuryłowicz 1965), at which time studies in grammaticization tended to be carried out in conjunction with the search for language universals and types (Bybee 1985, Bybee & Dahl 1989, Dahl 1985). Due to the availability of computer database software and the proliferation of a greater number of descriptions of the languages of the world, such studies were able to show well-defined patterns of grammatical development from very broad, statistically rigorous cross-linguistic samplings.

One of the most influential studies in this area, conducted by Joan Bybee and her colleagues and reported on in Bybee, Perkins & Pagliuca 1994, tested specific hypotheses concerning the grammaticization of tense and aspect forms on a stratified probability sample of 76 languages, proportionally representative of every language phylum. Bybee et al. examined the cross-linguistic development of progressive meaning and the forms used to realize that meaning.

While it may be somewhat controversial to invoke typological data to argue for or against a particular language-specific development, I believe such information can be heuristically useful. It is certainly true that all languages undergo unique external historical events that lead to language-specific changes; however, the cognitive apparatus that stores and organizes language is not unique to specific groups of humans, and therefore we find that many internal changes are similar across languages. These cognitive forces of change may have to do with other functions of the mind (for example, memory) or with issues of language use, such as frequency of use, semantic generality, etc. (Bybee 2001, Newmeyer 2003). In fact, Bybee et al. demonstrate the very strong similarities in terms of the ways that tense and aspect, including progressive, develop across languages.

One of the most important similarities in the development of grammatical categories has to do with what happens to a given form over time in terms of generality of meaning. Of the several grammaticization paths that Bybee et al. investigate, it is clear that semantic development regularly proceeds from more specific (often lexical or constructional) to more general meaning. Thus, it appears to be common enough that expressions for more specific areas within imperfectivity, such as progressivity, can expand their domain and thus give rise to imperfective forms. For instance, Comrie (1976:38–40) notes that in some languages, progressive forms have spread beyond pure progressive meaning and have taken on general present tense uses, an important development of which is the spread to include habitual meaning (see also Bybee et al. 1994:141, and below). For instance, in the related languages Irish, Welsh, and Scots Gaelic, the various stages of this extension in etymologically-related progressive forms are evident. In Irish, the form has a specific progressive meaning, ta sé ag dul ‘he is going’, whereas the Welsh cognate construction has both progressive and general, habitual meaning. For dynamic verbs, and even some stative verbs, this progressive in Welsh has extended to cover habitual meaning so that y mae ef yn mynd means ‘he goes’ or ‘he is going’. For stative verbs in Welsh, the form takes a habitual interpretation: y mae ef yn hoffi coffi ‘he likes coffee’. Finally, the same form in Scots Gaelic represents both meanings so that e a’ dol means both ‘he goes’ and’ he is going’, presumably depending on context. This change has also occurred in a number of other languages, including Yoruba and Turkish (Bybee & Dahl 1989:82).

Since this tendency in the semantic development of tense/aspect forms is very strong, the limiting of a verb form with so broad a semantic distribution as OE beon + PAP with its many imperfective (and even perfective) uses into a considerably more restricted progressive is highly suspect. Indeed, as I stated above, I believe the impetus to do so reflects an emphasis on formal identity, with less attention being paid to the semantic likelihood of such a development.14

Obviously, there is an explicit claim of unidirectionality here, which should not be taken in the strong sense. The issue of unidirectionality has been widely debated (see Campbell 2001 and the papers therein, as well as Traugott 2001). In fact, it is clear that there are indeed certain cases of reversal of the unidirectionality hypothesis on the formal level of development, particularly in terms of limiting scope and bondedness (Traugott 1995). However, in terms of the proposed specific → general path of semantic development, the trend is much more regular (see also Traugott & Dasher 2002). Furthermore, to my knowledge, there is no case where a broad imperfective category has been shown to develop progressive meaning in the way proposed for beon + PAP → progressive.

4. Progressive Meaning and the English Locative Construction.

As Bybee et al. (1994:135) point out, the attractiveness of linking the ModE progressive directly to the locative construction is strong, given that in their study the most ubiquitous source for progressivity is locativity. Of the 53 progressives in their sample of 76 languages, 23 have clear locative sources. Another seven have expressions involving movement such as come or go as their source, which can be thought of as dynamic locatives since they place the agent in a location, albeit moving around (Bybee et al. 1994:134).

The relationship between locativity and progressivity is apparent. If an agent is located at a specific place engaged in some activity, then it is a matter of profiling the activity rather than the place that leads to progressivity, the prototypical meaning of which given in Bybee et al. (1994:136) involves:

- (1) an agent

- (2) located spatially

- (3) in the midst of

- (4) an activity

- (5) at reference time

Indeed, when we consider early instances of the locative construction (and even present-day dialectal use of that construction with overt marking) the meaning aligns with this prototype, as in 2 (repeated here as 11 for convenience), where the meaning is primarily about the whereabouts of the king.

In later uses of the locative construction, both with a reduced prepositional element and after the prepositional element is no longer apparent, we see a shift away from locative meaning toward a focus on the activity. For instance, 12a is interpretable as being about either the location or the activity, while 12b is clearly about the activity.

The role of locativity as a source for progressive meaning is further suggested by the fact that it is still often an appropriate answer to questions about location, as in example 13 from Bybee et al. (1994:133, citing personal communication with Dwight Bolinger).

Ebert (2000:649) disagrees with the locative retention hypothesis here, claiming that the appropriateness of the answer is due to the assumption of “taking a bath” as limited to a specific place. However, in other cases where the location is not so fixed, the progressive is often used in a similar way, as in the exchange in 14, which does not seem like an egregious mismatch of question and information for many discourse situations.

In fact, the relationship between locativity and progressivity is not unique to English among Germanic languages. Ebert (2000) catalogs the sources for progressive meaning among Germanic languages and finds that locativity is the most frequent source, as in the German and Dutch examples in 15a,b.15

Theories about the progressive have also sought from time to time to uncover foreign influences from languages like Celtic and French. However, given the dearth of lexical influence from Celtic in English, I find assertions that that the locative and progressive have their sources in substratal retention or superstratal influence difficult to sustain, particularly in light of what similar case studies have shown regarding the ordering of lexical and grammatical borrowings (Thomason & Kaufman 1988). In fact, given the ubiquity of locative expressions in Germanic and even in Old English (on huntoþe, etc.), I see no appeal to calling in Celtic foreign influence in this area of the grammar (see Fischer 1992 on the unlikelihood of foreign influence).

These Germanic verbal locatives, however, have had a less than positive reception by normative grammarians. In German, for instance, the construction in 15a is relegated to “colloquial use” (see, for example, Drosdowski 1984), and it is not appropriate in the written Standard. What is particularly interesting is that the English locative suffered similar proscriptions, and these proscriptions are central to understanding the relationship between the English locative and the later progressive, particularly in terms of its formal similarity to the older beon + PAP.

5. Reconciling Form and Meaning.

Thus far, I have attempted to establish a reconstruction for the semantics of the progressive. In so doing, I have been skeptical of a development from the OE construction and have instead offered support for the position that the locative construction is a much more plausible source for progressive meaning. Some who have tried to defend a more direct link between the two constructions have changed their minds in light of the internal evidence, which seems to suggest continuous use of the OE beon + PAP throughout the history of English. An illustrative comment of defeat comes from Otto Jespersen who, after taking a strong position on the locative reconstruction in his first edition of Growth and Structure in 1901, retracted his original statement:

the modern English expanded tenses [that is, progressive] are in some vague way a continuation of the old combinations of the auxiliary verb and the participle in -ende; but after this ending had been changed into -inge and had thus become identical with that of the verbal substantive, an amalgamation took place of this construction and the combination be + on + the sb [substantive], in which on had become a and was then dropped […]”

(Jespersen 1949:169, emphasis mine)

Instead, he opts for a dual source account for the “increasing frequency of the construction” and “the much greater precision with which [it] is used in modern times” (p. 169). In fact, no few scholars on the history of English have come to a similar conclusion (for example, Elsness 1994, Fischer 1992, Hatcher 1951, Traugott 1972, Visser 1963), and this has become the dominate thinking in current theorizing on the origins of the progressive, even being offered in widely used introductory texts on the history of English (such as Baugh & Cable 2002).16

Specifically, Baugh & Cable (2002:292) put forward the notion that the locative construction was “a chief factor” in the growth of the “progressive forms.” However, they apparently view these “progressive forms,” that is copula + PAP instances, as dating from the OE period and thus espouse a dual source, quite in keeping with the Jespersen quote given above. Their calling the older English instances of beon + PAP “progressive forms” is a confusion of form and meaning. This confusion makes it difficult to understand how the relevant historical forms and the meanings they come to signal coincide.

To return to the data in table 2, we have seen the frequency of the copula + PAP syntagm in Middle and Early Modern English. The data from the table also show that before 1500 the frequency of copula + PAP with progressive meaning and the frequency of copula + PAP with other imperfective meanings is about equal, although in the period from 1150–1250 other imperfective meanings occur more often. After 1500, however, occurrences of copula + PAP are nearly always progressive. In other words, it is from 1500 that progressive meaning becomes situated more stably in the copula + PAP form (see also Fischer 1992 and Strang 1982). It is important to bear in mind that historical tokens after the OE period simply appear as copula + PAP. As stated earlier, there is no way of knowing whether a specific instance of copula + PAP represents an aphetic locative (such as an instance of a- + -ing after the loss of the initial unstressed vowel) or a literary continuation of the older beon + PAP (as in Dutch). What I propose is that the dearth of locative construction tokens in written English (only 14 from the 2.5 million-word database studied here) vis-á-vis ubiquitous occurrence in spoken, nonstandard varieties of present-day English (see, for example, Wolfram & Schilling-Estes 2005) belies language proscription. Normative practices are also suggested by the rather fast regularization and conventionalization of progressive meaning in the copula + PAP instances in Modern English.

In order to investigate the role of Early ModEng normative practices involving copula + PAP, I carried out a survey of 35 randomly selected, early grammars of English spanning the years 1530–1797, that is, spanning the Early ModEng period. First, it is important to note that about half of the grammars—the earliest ones—make no mention of the copula + PAP or the locative construction at all, and neither form is mentioned until the 18th century in the sample I consulted. Rissanen (1999:216), however, cites Cooper (1685), who was the first to mention a copula + PAP form. Cooper then is rare among the early grammars and inclusion of the form in grammatical treatments of English really belongs to the later ModE period. I take this to be indicative of the fact that the grammarians of the time were more concerned with making the English tense-aspect system look as much like that of a classical language as possible, and of course in normative grammars it is not uncommon to find simple denial of “inconvenient” or recently emerged structures. When the locative construction is discussed, its treatment is consistent, thus suggesting that its use had become conventionalized some time earlier in normative practices.

Of the 35 sample grammars, only four make any explicit mention of the locative construction, at the same time proscribing it, as the passage in 16 shows.

Statements like that in 16 actively relegate the locative to non-written usage (“familiar discourse”) and, again, this had likely been the practice for some time (compare am-locatives in German). This position is supported by pronouncements, such as 17.

From its first uses, the locative construction could signal both active and passive meanings, as the cited instances in this example show. Two important, and somewhat interrelated points, are to be made. First, beon + PAP did not have passive uses, and therefore when we find passive uses of bare copula + PAP (for example, “the new coach was building,” Austen 1980:173), they are to be taken as instances of the aphetic locative. Second, the proscription of the locative element is not limited to only the passive uses of the locative construction, as is clear from examples like that in 19 (see below). Then, if the prescription of aphesis was successful with passive uses, we should expect that it was also successful with active uses.

Here the form is not merely dismissed from written English (“in familiar conversation”), but the locative element is proscribed (“it ought to be omitted”). Thus, grammar practice following Ussher's edict would have resulted in a coalescence of the two historical sources, at least formally, since it would have encouraged use of the aphetic locative.

Already it is clear that there was a practice of suppressing the locative form among grammarians of the period. However, it may have been that their acceptance of aphetic forms was due to familiarity with the historically well-documented copula + PAP, qua literary continuation of the OE beon + PAP construction. If so, then it is quite interesting that the beon + PAP construction may be said to have played a role as a formal model in the development of the present-day progressive. In 18, for instance, we find that the prefixal vowel is again proscribed and deemed inelegant.

However, Buchanan calls the locative element “redundant” and “superfluous,” a clear indication that he is aware of the occurrence of an alternate form without the locative element. In other words, he is prescribing the aphetic locative at the expense of the construction with an overt locative marker. The question is to what degree his and other grammarians’ views were informed by knowledge of the bare copula + PAP qua literary continuation of the beon + PAP construction in historical literary English.

It is well known that historical occurrence was very often invoked as authority in the prescriptions of the early grammarians. As Bartsch (1987:238–239; quoted in Stein 1994:7) indicates, the selection of a given variety for the Standard will often be “a variety [which has] a history of literature with ‘great’ authors.” Since the bare copula + PAP appears often enough in English before the 19th century, grammarians like Buchanan would certainly have known this as they were familiar with authors such as Chaucer, a ME source in which bare copula + PAP occurs rather frequently (and uncharacteristically for ME writers). The quote in 19 from Greenwood supports the idea that the preference for the aphetic form may have been due to familiarity with the historically continued uses of beon + PAP.

Greenwood claims that the a- is “set before the Participle,” perhaps an indication that he views the bare form as basic in some sense and the locative form as derived. Perhaps, too, he saw this as a historical derivation, as his use of “Saxon” suggests. Thus, Greenwood seems to be invoking historical uses of bare copula + PAP as justification for his proscription of the locative element, uses he would have been familiar with from older English texts. Strong evidence for a historical appeal to beon + PAP and its later English continuation) is lacking, however, and we may never know to what degree the older construction influenced the Early Modern English grammarians’ tastes.

Nevertheless, it is clear that these grammarians were successful in their proscriptions given the nearly complete eradication of the locative progressives in the Standard and given the stigmatized position of the locative in Modern English (see also Nehls 1974).18

Having been born into and raised in a speech community where prefixal a-participles are used, I am well aware of the effects of register, genre, and education on the frequency of the form. Among older members, who also tend to be less educated in the Standard, prefixal participles are extremely frequent in very familiar discourse, whereas among younger speakers, especially those who are still in school or are in regular contact with speakers outside of their own speech community, the form is essentially absent.

The progressive has continued to develop in Modern English since the 18th century; for instance, its use with stative verbs of emotion or mental state, as in I am loving it! While much more research on this phenomenon is called for, such uses, I think, are best viewed not as grammaticization per se, but pragmaticiza-tion, that is, the use of the construction to strengthen a speaker's subjective positioning in discourse construction, a typical and expected development of later stages of grammaticization (Traugott 1989).

6. Conclusion.

I hope to have strengthened the plausibility of a more direct link between the locative construction and the progressive by invoking the strong universal relationship between locativity and progressivity. While these arguments cannot definitively prove that link for English, I believe they do encourage us to reconsider that position more seriously as we build our theories on the development of the English progressive. After all, theories about the structural development of English should accord with what we know to have happened or be happening in the languages of the world. Any theory that involves a counter claim to the strongly supported patterns of narrow to broad semantic trends in the development of tense and aspect, as do reconstructions of the type beon + PAP → progressive, carries a greater onus to show why and how such an irregular development could happen in terms of a linguistically plausible theory. To date, however, such explanation has not been forthcoming.

Nevertheless, we do need to be careful about dismissing beon + PAP too quickly or altogether because, even though its numbers dwindle considerably at the close of the OE period, the construction continues to appear in Middle English, where its semantic content is still quite broad and, as I have suggested, represents a literary continuation of the OE construction in a way not unlike that in other Germanic languages, such as Dutch. Many researchers working on the history of the progressive who have been sensitive to form and meaning have suggested some sort of amalgamation of the continued uses of the copula + PAP and the locative construction. In this paper, I have provided an explanation for a formal merger as having been encouraged by normative grammar practices in the Early Modern period. Still, the evidence in toto is weighted more strongly in favor of a reconstruction of the ModEng progressive out of the locative construction, with beon + PAP and its continued ME uses providing, perhaps, a formal model that informed Early ModE prescriptive practice.

APPENDIX

The following references are the sources (editions) of the texts used to collect all instances of copula + PAP (including copula + nominal -end in Old English), the coding for which is discussed in section 2. The sampling procedure for these texts largely follows that of the diachronic portion of the Helsinki Corpus:

http://khnt.hit.uib.no/icame/manuals/hc/index.htm

and from the Corpus of Early English Correspondence:

http://khnt.hit.uib.no/icame/manuals/ceecs/index.htm.

Additionally, for this study the entire texts of Beowulf, Layamon, The Arte of English Poesie, the Poems of Robert Henryson, Havelock the Dane, King Horn, the Scholemaster, Essays (Francis Bacon), and Paradise Lost were included, since those texts comprised the pilot collection phase of the study before the Helsinki Corpus was available to me.

Primary Sources

Old English

Assman, Bruno. 1964. Anglesächsische Homilien and Heiligenleben. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftlische Buchgesellschaft.

Birch, Walter de Gray (ed.). 1964. Cartularum Saxonicum: A collection of charters relating to Anglo-Saxon history, vol. 2. London: Johnson Reprint Company.

Cox, Robert S. (ed.). 1972. The Old English dicts of Cato. Anglia 90.1–42.

Crawford, Samuel J. (ed.). 1966. Byrhtferth's manual, vol. 1. (Early English Text Society 177). London: Oxford University Press.

Crawford, Samuel J. (ed.). 1922. The Old English version of the Heptateuch. Reprinted in 1969 with additions by N. R. Ker. (Early English Text Society 160). London: Oxford University Press.

Cross, James E. & Thomas D. Hill (eds.). 1982. The prose Solomon and Saturn and Adrian and Ritheus. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Dickins, Bruce & Alan S. C. Ross. 1959. The dream of the rood. London: Methuen.

Dobbie, Elliot Van Kirk. 1942. The Anglo-Saxon minor poems. (The Anglo-Saxon poetic records VI). New York: Columbia University Press.

Fehr, Bernard (ed.). 1966. Die Hirtenbriefe Ælfrics (with a supplement by Peter Clemoes). Darmstadt: Wissenshaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Harmer, Florence E. (ed.). 1914. Select English historical documents of the ninth and tenth centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Klaeber, Friedrich (ed.). 1950. Beowulf and the fight at Finnsburg. Lexington, MA: D. C Heath & Company.

Krapp, George P. 1931. The Anglo-Saxon poetic records, vol. 1. London: George Routledge & Sons.

Libermann, Felix (ed.). 1903. Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen, vol. 1. Halle: Max Niemeyer.

Miller, Thomas. 1959. The Old English version of Bede's ecclestiastical history of the English people. (Early English Texts Society 95, 96). London: Oxford University Press.

Morris, Richard (ed.). 1873. The Old English homilies of the twelfth century, second series (Early English Text Society 53). London: Oxford University Press.

Pope, John. C. (ed.). 1981. Seven Old English poems. 2nd edn. New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Robertson, Agnes J. (ed.). 1956. Anglo-Saxon charters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Skeat, Walter W. (ed.). 1871–1887. The Holy Gospel in Anglo-Saxon, Northumbrian and Mercian versions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sweet, Henry (ed.). 1958. King Alfred's West-Saxon version of the Gregory's pastoral care, 2 vols. (Early English Text Society 45, 50). London: Oxford University Press.

Vleeskruyer, Rudolf (ed.). 1953. The life of St. Chad: An Old English homily. Amsterdam: North Holland.

Whitelock, Dorothy (ed.). 1930. Anglo-Saxon wills. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Whitelock, Dorothy. 1967. Sweet's Anglo-Saxon reader in prose and verse, revised by Dorothy Whitlock. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Middle English

Atkins, John W. H. (ed.). 1922. The owl and the nightingale (edited with introduction, texts notes, translation, and glossary). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/mideng.browse.html (5 June 2007).

Beadle, Richard (ed.). 1982. The York plays. London: Edward Arnold.

Bennet, Jack A. W. & Geoffrey V. Smithers. 1968. Early Middle English verse and prose. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Blake, Norman F. (ed.). 1970. The history of Reynard The Fox, translated from the Dutch original by William Caxton. (Early English Text Society 263). London: Oxford University Press.

Brook, George L. & Roy F. Leslie (eds.). 1963, 1978. Layamon, edited from British Museum Ms. Cotton Caligula AIX. and British Museum Ms. Cotton Otho C.XIII. (Early English Text Society 250, 277). London & New York: Oxford University Press.

Bülbring, Karl D. 1891. The earliest complete English prose psalter. (Early English Text Society 97). London: Oxford University Press.

Chambers, Raymond W. & Marjorie Daunt. 1967. A book of London English 1384–1425. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Chaucer, Geoffrey (d. 1400). The Canterbury Tales. [General Prologue, The Knight's Tale, The Miller's Tale, The Wife of Bath's Tale (First 705 lines)]. http://etext.virginia.edu/mideng.browse.html (5 June 2007).

D'Ardenne, Simonne T.R.O. (ed.). 1977. The Kathrine Group, edited from the MS. Bodley 34. Biblioteque de la faculte de philosophie et letters de l'universite de Liege, CCXV. Paris: Societe D'Edition “Les Belles Lettres.”

Davis, Norman. 1971. Paston letters and papers of the fifteenth century. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Dawson's of Pall Mall. 1963. The Statutes of the Realm printed by Command of His Majesty King George the Third in pursuance of an address of the House of Commons of Great Britain, vol. 2.

Dickins, Bruce (ed.). 1938. Sawles Ward: An early Middle English homily. (Leeds School of English Language Texts and Monographs 3). University of Leeds. http://etext.virginia.edu/mideng.browse.html (5 June 2007).

Dickins, Bruce & Richard M. Wilson (eds.). 1956. Early Middle English texts. London: Bowes & Bowes.

Fisher, John H., Malcolm Richardson & Jane L. Fisher (eds.). 1984. An anthology of chancery English. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press.

Fjorshall, Josiah & Frederic Madden (eds.). 1850. The New Testament in English according to the version by John Wycliffe about A.D. 1380 and revised John Purvey about A.D. 1388. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Francis, Winthrop Nelson (ed.). 1942. A fourteenth century English translation of the Somme le Roi of Lorens D'Orleans. (Early Engish Text Society 217). London: EETS.

Gairdner, James (ed.). 1876. The historical collections of a citizen of London in the fifteenth century. No. 17. Westminster: The Camden Society.

Hall, Joseph (ed.). 1963. Selections from Early Middle English 1130–1250, part 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Henryson, Robert. 1906–1914. The poems of Robert Henryson (printed for the Scottish Text Society). Edinburgh & London: W. Blackwood & Sons. http://etext.virginia.edu/mideng.browse.html (5 June 2007).

Herzman, Ronald B., Graham Drake & Eve Salisbury (eds.). 1999. Havelock the Dane. (Originally published in Four Romances of English). http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/tmsmenu.htm (5 June 2007).

Herzman, Ronald B., Graham Drake & Eve Salisbury (eds.). 1999. King Horn. (Originally published in Four Romances of English). http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/tmsmenu.htm (5 June 2007).

Hudson, Anne. 1983. English Wycliffite sermons, vol. 1. Oxford: Clarendon.

Kerønen, Jukka, Terttu Nevalainen & Arja Nurmi (eds.). 1996. Letters from the Marchall correspondence. Public Records Office, SC. 1.

Morris, Richard (ed.). 1863. The pricke of conscience. Berlin: A. Asher & Co.

Morris, Richard (ed.). 1873. The Old English homilies of the twelfth century, second series (Early English Text Society 53). London: Oxford University Press.

Ogden, Margaret S. (ed.). 1971. The cyrurgie of Guy de Chauliac (Early English Text Society 265). London: Oxford University Press.

Pollard, Alfred W. (ed.). 1903. Le morte d'Arthur: Sir Thomas Malory's book of King Arthur and of his noble knights of the Round Table. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd. http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/ (5 June 2007).

Price, Derek J. 1955. The Equatorie of the Planetis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ross, Woodburn O. (ed.). 1940. Middle English sermons (Early English Text Society 209). London: Oxford University Press.

Shores, David L. 1971. A descriptive syntax of the Peterborough Chronicle from 1122–1154. The Hague: Mouton.

Stapleton, Thomas (ed.). 1839. A series of letters, chiefly domestick, written in the reigns of Edward IV, Richard III, Henry VII, and Henry VIII. (Camden First Series 4). London: J.B. Nicols & Son.

Svinhufvud, Anne C. 1978. A late Middle English treatise on horses. (Stockholm Studies in English 47). Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksell International.

Tolkien, John R. R. (ed.). 1962. Ancrene Wisse (Early English Text Society 249). London: Oxford University Press.

Wright, William A. (ed.). 1887. The metrical chronicle of Robert of Gloucester, part II. London: Rolls Series 86.

Early Modern English

Alston, Robin C. (ed.). 1969. A new discovery of the old art of teaching schoole. Menston: The Scholar Press Limited.

Arber, Edward (ed.). 1869. Seven sermons before Edward VI, on each Friday in Lent, 1549. London: Murray & Son.

Ascham, Roger. 1570. The scholemaster. http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/modeng/modengA.browse.html (5 June 2007).

Bacon, Francis. 1996 [edition by Project Gutenburg]. Essays. http://www.promo.net/pg/ (5 June 2007).

Brett-Smith, Herbert F. B. (ed.). 1920. Gammer Gvrton's nedle. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/modeng/ (5 June 2007).

Bruce, John. 1844. Correspondence of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leycester, during his government of the Low Countries, in the years 1585 and 1586. (Camden First Series 27). London: J. B. Nicols & Son.

Bruce, John. 1968. Annals of the first four years of the reign of Queen Elizabeth. London: Camden Society.

Campagnac, Ernest T. (ed.). 1917. Ludus literarius or the grammar schoole. Liverpool & London: Constable & Co.

Coutts, Francis (ed.). 1907. The marriage ring. London & New York: John Lane.

Coverte, Robert. 1971. A true and almost incredible report of an Englishman. (The English Experience 302, facsimile). Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Ltd.

Darnell, William Nichols (ed.). 1831. The correspondence of Isaac Basire, D. D. Archdeacon of Northumberland and Prebendary of Durham, in the reigns of Charles I and Charles II with a memoir of his life. London: John Murray.

Dawson's of Pall Mall. 1963[1817]. The statutes of the realm printed by command of His Majesty King George the Third in pursuance of an address of the House of Commons of Great Britain, vol. 3.

De Beer, Esmond S. 1959. The diary of John Evelyn. London: Oxford University Press.

Donno, Elizabeth S. 1976. An Elizabethan in 1582: The diary of Richard Madox, fellow of all souls. London: Hakluyt Society.

Fabyan, Robert. 1516. The new chronicles of England and France. London: Pynson.

Farquhar, George. 1972. The beaux stratagem. Menston: The Scholar Press.

Furnivall, Frederick J. & Percy Furnivall (eds.). 1888. The anatomie of the bodie of man. (Early English Text Society 53). London: Oxford University Press.

Gardiner, Samuel Rawson (ed.). 1968. Letters to the council to Sir Thomas Lake, relating to the proceedings of Sir Edward Coke at Oatlands (Camden First Series 87). London: J. B. Nicols & Son.

Gifford, George. 1931. A handbook on witches and witchcraft: A dialogue concerning witches and witchcrafts. (Shakespeare Association Facsimiles 1, with an introduction by B. While). London: Humphrey Milford and Oxford University Press.

Griffin, Richard (ed.). 1842. The private correspondence of Jane Lady Cornwallis; 1613–1644. London: S. & J. Bently, Wilson & Fley.

Gunther, Robert T. 1968[1938]. Early science in Oxford, vol. 13: The life and work of Robert Hooke, part 5. London: Dawsons of Pall Mall.

Koekeritz, Helge (ed.). 1955. Mr. William Shakespeare's comedies, histories, and tragedies. London: Geoffrey Cumberlege, Oxford: Oxford University Press, and New Haven: Yale University Press.

Krapp, George P. (ed.). 1932. The works of John Milton, vol. 10. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lawlis, Merritt. E. (ed.). 1961. The novels of Thomas Deloney. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Loftie, William J. (ed.). 1884. Ye oldest diarie of Englysshe travell: Being the hitherto unpublished narrative of the pilgrimage of Sir Richard Torkington to Jerusalem in 1517. (The Vellum-Parchment Shilling Series of Miscellaneous Literature 6). London: Field and Tuer, Ye Leadenhalle Presse.

Macaulay, George C. (ed.). 1910. The chronicles of Froissart. New York: P. F. Collier & Son Company. http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/ (5 June 2007).

Marquis of Bristol (ed.). 1968. Five letters of King Charles II. Camden Miscellany 5. (Camden First Series 87). London: J. B. Nicols & Son.

Milton, John. 1991 [Project Gutenburg edition]. Paradise Lost. http://promo.net/ (5 June 2007).

Oesterly, Hermann (ed.). 1866. Shakespeare's jest book: A hundred mery talys, from the only perfect copy known. London: John Russell Smith.

Ornsby, George (ed.). 1868. The correspondence of John Cosin, D. D. Lord Bishop of Durham, part 1: Together with other papers illustrative of his life and times. (Publications of the London Surtees Society.) Durham, UK: Andrews & Co.

Pollard, Alfred W. (ed.). 1911. An exact reprint in Roman type, page for page of the authorized version published in the year 1611, with an introduction by A. W. Pollard. London: Henry Frowde.

Puttenham, George. 1968. The Arte of English Poesie. (Scholar Press facsimile of the first edition). Menston: Scholar Press.

Raine, James (ed.). 1843. The correspondence of Dr. Mathew Hutton, Archbishop of York: With a selection from the letters, etc. of Sir Timothy Hutton, Knt., his son; and Matthew Hutton, Esq., his grandson. (Publications of the Surtees Society 17.) London: J. B. Nicols & Son.

Rhys, Ernest (ed.). 1907. The Boke named the Governour. New York & London: J. M. Dent & Co.

Smith, Henry. 1975. Two sermons on “of usurie.” A preparative to mariage; of the lord's supper; of usurie. (The English Experience 762). Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum.

Stapleton, Thomas (ed.). 1839. A series of letters, chiefly domestick, written in the reigns of Edward IV, Richard III, Henry VII, and Henry VIII. (Camden First Series 4). London: J. B. Nicols & Son.

Thompson, Edward M. (ed.). 1965. The Camden miscellany, volume the eighth: Containing correspondence of the family of Haddock, 1657–1719. (Camden Society 31). New York: Johnson Reprint Corporation.

Thompson, Roger (ed.). 1976. Samuel Pepys’ “Penny merriments.” London: Constable & Company.

Wallis, Norbert H. (ed.). 1938. The New Testament translated by William Tyndale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.