0 INTRODUCTION

The acquisition of two languages by a child involves a progression through different stages before reaching the fluency of a balanced bilingual. The process of this acquisition includes not only the linguistic development but is also influenced by psychological, cognitive, neurological and social features (Becker, Reference Becker1997; Carlisle, Beeman, Davis and Spharim, Reference Carlisle, Beeman, Davis and Spharim1999; Cohen, Reference Cohen1980; Cromdal, Reference Cromdal1999; Döpke, Reference Döpke1992, 1997; Downes, Reference Downes1998; Fantini, Reference Fantini1985; Fortkamp, Reference Fortkamp1999; Genishi, Reference Genishi1999; Gumperz, Reference Gumperz1977, Reference Gumperz1982; McClure, Reference McClure and Saville-Troike1977; Myers-Scotton, Reference Myers-Scotton1993a; Romaine, Reference Romaine1994; Segalowitz and Lightbown, Reference Segalowitz and Lightbown1999). Bilingual child language development has been increasingly discussed and has been distinguished from adult bilingualism, based on a different level of language awareness and cognitive development (Barron-Hauwaert, Reference Barron-Hauwaert2004; Bauer, Hall and Kruth, Reference Bauer, Hall and Kruth2002; Comeau, Genesee and Lapaquette, Reference Comeau, Genesee and Lapaquette2003; Harding-Esch and Riley, Reference Harding-Esch and Riley2003; Lanvers, Reference Lanvers2001; Nicoladis and Genesee, Reference Nicoladis and Genesee1996.) One major process that individuals generally encounter during simultaneous acquisition of several languages is code-switching or code-mixing, an alternation of languages within the same discourse or speech act (Auer, Reference Auer1998; Genesee, Paradis and Crago, Reference Genesee, Paradis and Cargo2004; Grosjean, Reference Grosjean1982; Myers-Scotton and Ury, Reference Myers-Scotton and Ury1977). Genesee et al. (Reference Genesee, Paradis and Cargo2004: 91) defines it as the use of elements from two languages in the same utterance or in the same stretch of conversation’. These alternations are motivated by a number of factors, such as social, topical, situational and psychological factors, which are commonly found in most bilinguals’ speech, regardless of their age. Indeed, children's bilingual speech seems to follow similar influence of social, topical, situational or psychological factors (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Hall and Kruth2002; Genesee, Nicoladis and Paradis, Reference Genesee, Nicoladis and Paradis1995; Nicoladis and Genesee, Reference Nicoladis and Genesee1996, Reference Nicoladis and Genesee1997).

The present case-study examines the code-switching of a four-year-old English-French bilingual boy, and investigates some of the particular functions motivating his situational code-switching, in order to better comprehend his pragmatic choices. Code-switching, caused by pragmatic reasons, can be stimulated by situational changes (such as interlocutors, settings or topic shifts), or to emphasise, quote, protest, narrate, etc. (Genesee et al., Reference Genesee, Paradis and Cargo2004; Gumperz, Reference Gumperz1982; Gumperz and Hernandez-Chavez, Reference Gumperz, Hernandez-Chavez, Cazden, John and Hymes1972; McClure, Reference McClure and Saville-Troike1977; Yumoto, Reference Yumoto1996). This young boy is raised by an English-speaking mother speaking solely French to him, while being surrounded by English through his father, his extended family, daycare and the rest of the community. Romaine (Reference Romaine1995: 185) identifies the mother as a ‘non-native parent’, since the parent has the same native language as the dominant language of the community. However, one parent ‘always addresses the child in a language which is not his/her native language’. In this particular study, the term ‘code-switching’ will be defined according to Genesee et al. (Reference Genesee, Paradis and Cargo2004), as being a mix of elements from two languages within a conversation or within a sentence. The subject of this study frequently employed utterances in French and English within the same interactions. In addition to the need to better understand child language development, the environment makes this study significant and necessary, as both parents are native-speakers of the community dominant language (English) with one of the parents speaking only a second language (French) to the child (Döpke, Reference Döpke1992; Saunders, 1982); furthermore, this study suggests unusual functions for situational code-switching, as well as focuses on French, which is not a well-documented language in the field of code-switching.

This paper will first review the existing research dealing specifically with situational code-switching in children's speech. The methodology for the case-study will then be addressed, followed by the analysis and discussion of the data collected during the study.

1 EXISTING RESEARCH

Previous studies have shed a tremendous light on the research of child bilingualism and code-switching (Auer, Reference Auer1998; Barron-Hauwaert, Reference Barron-Hauwaert2004; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Hall and Kruth2002; Cook-Gumperz, Reference Cook-Gumperz1985; Döpke, Reference Döpke1992, 1997; Genesee et al., Reference Genesee, Paradis and Cargo2004; Genishi, Reference Genishi1977; Gumperz, Reference Gumperz1977, Reference Gumperz1982; Harding-Esch and Riley, Reference Harding-Esch and Riley2003; McClure, Reference McClure and Saville-Troike1977; Nicoladis and Genesee, Reference Nicoladis and Genesee1996, Reference Nicoladis and Genesee1997, Reference Nicoladis and Genesee1998; Yumoto, Reference Yumoto1996), but some questions remain to be answered in order to fully understand the linguistic selection of bilingual individuals, particularly regarding the situations that cause code-switching among bilingual children.

Code-switching has been considered as pragmatically or socially motivated, not only among adult bilinguals, but also with children (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Hall and Kruth2002; Genesee, Nicoladis and Paradis, Reference Genesee, Nicoladis and Paradis1995; Nicoladis and Genesee, Reference Nicoladis and Genesee1996, Reference Nicoladis and Genesee1997). The theoretical background suggests several models to explain the language choice of bilingual individuals. According to Scotton and Ury (Reference Scotton and Ury1977), code-switching is stimulated by three main social arenas: identity, power and transaction, with the code sometimes based on the appropriateness of any of these situations. McConvell (Reference Heller1988) proposes a model, where the social arenas can overlap each other, as they might not be well defined in the speakers’ mind, and therefore can provoke a language switch at any given moment. The Markeness Model, suggested by Myers-Scotton (Reference Myers-Scotton1993b), also brings the idea that the social and psychological aspects of language switch might have a crucial influence on the language. For some bilingual speakers, the unmarked matrix is replaced by the marked language, in order to integrate or belong to a group. Another model, the language socialisation framework (Ochs & Schieffelin, Reference Ochs, Schieffelin, Fletcher and MacWhinney1995; Lanza, Reference Lanza, Cenoz and Genesse2001), attempts to explain the pragmatic and social decisions children are able to make with their two languages. Indeed, through an understanding of the social and cultural milieu, a child is able to create his or her identity within a community and within interactions. This sociolinguistic approach could therefore explain the use of situational code-switching among bilinguals, including children, since the use of code-switching may be caused by intentional decisions. This brief discussion shows that the underlying functions of code-switching are mostly socially and pragmatically motivated, and as Vygotski (Reference Vygotski1978) initially remarked, children (not specifically in a bilingual environment) can be influenced by similar processes to adults, since they adapt to others using ‘social speech’.

Nicoladis and Genesee (Reference Nicoladis and Genesee1997: 265) claim that situation code-switching is a natural process for young bilingual children, partially based on pragmatic differentiation and understanding of the world around them. They state that ‘when they learn language, children learn the ways of expressing themselves and communicating with others that are characteristics of the social situations that are typical and important in their families and communities’. Genesee et al. (Reference Genesee, Paradis and Cargo2004) explain children's code-switching through pragmatic reasons as well. Emphasising, quoting, protesting, narrating and expressing themselves emotionally are possible stimulations for switching from one language to another. Children are aware of the environment they are in or the interlocutors they are with, and will consequently use the appropriate language. This type of code-switching has been qualified as situational code-switching, as it is stimulated by the situation, more specifically, by the interlocutor, the setting and the topic shift surrounding the bilingual speaker (Gumperz & Hernandez-Chavez, Reference Gumperz, Hernandez-Chavez, Cazden, John and Hymes1972; McClure, Reference McClure and Saville-Troike1977; Titone, Reference Titone1987; Yumoto, Reference Yumoto1996). Heller (Reference Heller1988) asserts that situational code-switching is rooted in distinct groups of activities that are socially separate and to which a specific language belongs. Genishi (Reference Genishi1977: 4) claims that in situational code-switching ‘the speaker's perception of the ongoing activity changes’. That is to say, the bilingual individual is aware of the situations surrounding him or her and can adapt to them with necessary language changes.

Based on observational studies, situational code-switching fulfills specific functions, such as quoting another speaker (quotation), specifying a particular addressee (addressee specification), clarifying a potential or apparent lack of understanding (clarification), elaborating (elaboration), emphasising a constituent within a sentence (focus), attracting and retaining the attention (attention, attraction or retention), marking a desired change in topic (topic shift), and interrupting a study with a rhetorical request or direct address to the audience (parenthesis or personalization versus objectivisation) (McClure, Reference McClure and Durán1981). Fantini (Reference Fantini1985: 59) also presents categories for code-switching based on social situations: exchange of information, intention of shocking, amusing, or surprising, underscoring, replicating, or emphasising. The forms code-switching can take are: ‘a) play; b) quoting, or citing a quotation; c) role play; d) story-telling; e) songs; f) jokes’. Titone (Reference Titone1987: 7–8) mentions that code-switching can occur for psychological reasons (‘endogenous factors’), as well as social/cultural reasons (‘exogenous factors’). He lists the exogenous factors as follows: tendency to adapt communicational forms to the interlocutor, ‘showing off’ for social consideration, change of context, the need to adhere to the authenticity of quotations, for the sake of emphasis, terminology needs, a two-level context (formal and familiar statements) and other miscellaneous factors. McClure's, Fantini's and Titone's categories overlap, supporting the observation that bilinguals display similar use of code-switching across age and socio-cultural contexts.

Empirical results show evidence that children code-switch based on situational changes. A few decades ago, Foster-Meloni (Reference Foster-Meloni1978) presented a case-study where a bilingual child (6;5 to 8;0), raised under the one person-one language principle had acquired Italian (through the father and the community language) and English (through the mother). The researcher observed that the child code-switched according to the situation, the topic or the setting. The contexts in which he switched to Italian were on school, swimming lessons, peer conversation, occupations and other unclassified topics. In a longitudinal study, Saunders (Reference Saunders1988) observed his own three children (from birth through teenage years) learning English and German in an English-speaking community (Australia) and recorded their speech and the patterns of their code-switching for 13 years. Their language switches were influenced by the parent with whom they were interacting, the activity taking place (e.g. role play), the context, and the portion of speech the children were recalling. Lanza (Reference Lanza1992) studied a two-year-old Norwegian and English bilingual child, also raised with the one person-one language strategy. Data were collected over a period of 7 months (from age 2;0 to 2;7) through audio-taped interactions between the parents and the child, diary notes from the mother, interviews and observations from the author. Lanza found that the age of her participant was not a factor in the occurrence of code-switching, as the young child showed clear sensitivity within the contexts she was in. Her code-switching was situational as she was able to differentiate between her parents and their own dominant languages (i.e., father with Norwegian and mother with English). In Lanvers (Reference Lanvers2001), the speech of two young bilingual children (1;6 to 2;11) was analysed in order to observe the instances of switching, in a grammatical and pragmatic context. Lanvers found that despite their young age, the children made use of single-word code-switching to emphasise, appeal, quote or switch topics. This study supports the awareness that young bilingual children have of the social role of code-switching. Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Hall and Kruth2002) observed in a study of a bilingual child that play activities could be a factor for code-switching. They studied the speech of a German-English bilingual child (2;0 to 3;0), as she was interacting with adults in the context of play. In most play situations, she used mostly the language of the interlocutors. Yet, in the case where she was directing the play, English was chosen significantly more often. This result shows that she had developed pragmatic competence and was able to distinguish between interlocutors and leadership of play. Comeau et al. (Reference Comeau, Genesee and Lapaquette2003), through a study of six French-English bilingual children (average age 2;4) in a preschool context, examined a significant change in the rate of children's code-switching based on the interlocutors’ amount of mixing. As the previously discussed research has shown, these results indicated that children are sensitive to their interlocutors’ speech and that interlocutors have an influence on their own language choice.

Despite empirical studies and lists of factors that trigger code-switching, Winford (Reference Winford2003) mentions that the present taxonomies do not account for all code-switches. Genesee et al. (Reference Genesee, Paradis and Cargo2004: 102) have also noted: ‘BCM [bilingual code-mixing] has multiple explanations, and more than one can apply to the same situation or conversation. In other words, no single explanation accounts for all BCM’. Indeed, even though the functions justifying situational code-switching are relatively numerous, some data in the present study cannot be explained. Therefore, the intent of this study is to better understand the role behind the use of two languages and to provide more data on situational code-switching by expanding the categorisation in the case of a young English-French bilingual. The following research questions arise and will guide the content of this paper: Can a child raised by a non-native parent produce situational code-switching triggered by topic changes? Are there new topics or roles to add to the previous literature that trigger a young English-French bilingual child to code-switch?

2 METHODOLOGY

Raising a child bilingually in a monolingual society with only one parent speaking the second language is a challenging task for a parent and his or her child. Saunders (Reference Saunders1988) reported a similar situation, with his three children being raised as English-German bilinguals in an English-speaking community (Australia). This case-study explores this very situation over a period of three months, with a non-native speaker of French teaching French to her child. The community surrounding the child and the mother was all English-speaking, as this study took place in the state of Indiana, United States. It is important to mention that the researcher received access to the participants through the mother of the child.

To better understand the context of this reality, it is important to first introduce the child and the interlocutors that were involved, the settings where the study took place, and to explain how the data was collected.

2.1 Participants

2.1.1 The child

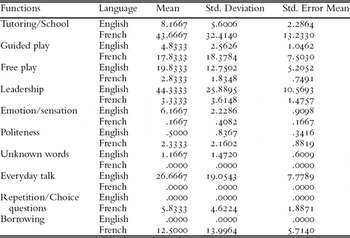

The child, called Benjamin for the purpose of this study, is American (born of two American parents in the United Stated) and was an only child at the time of this study. Interested in her own child's linguistic behaviour, the mother, who was the professor of the researcher, happily agreed to let her child participate in this study. Benjamin was observed between the age of 4;1 and 4;4. Since birth (more precisely, in utero), his mother only spoke French to him as she and her husband had chosen to raise him with two languages in order to make him more aware of others and give him more opportunities for his future. According to the parents and his tutor, he was lexically and syntactically more advanced in spoken English due to a greater exposure to the language. Indeed, he lived in the United States, went to daycare where he interacted in English with other children, and his extended family was all English-speaking. Yet his listening proficiency was fully developed in both English and French. No Mean Length of Utterance was calculated to support this claim; however, as seen later on, the amount of English predominantly occupied Benjamin's everyday speech. Most of his natural speech, in situations not created by other, occurred in English. Nicoladis and Genesee (Reference Nicoladis and Genesee1997) mention that in most cases of bilingual children, there is a dominant language. Because both his parents worked, Benjamin attended daycare during the day, making English the principal language of his environment. The opportunities he had to speak and hear French were with his mother (at home in the morning, in the evening and on weekends) and with a private tutor (one hour per week). The summer prior to this study, Benjamin had also spent a few weeks in a French-speaking daycare centre in Québec, which increased significantly his production of French according to his tutor and mother. The claim of his dominance of English is supported by the data collected for this study. Indeed from the data collected from specific situations where he was encouraged to speak French, 56.9% of Benjamin's utterances were still in English (Table 1). In an everyday context, with his mother and the tutor, he would speak 100% of the time in English (Table 1). However, it is important to note that all videos, except for a few minutes during breakfast and baking time, were centred on learning French, which was not representative of Benjamin's everyday life, since he was only 4. During those learning periods, he was strongly encouraged, by reminders, to speak French. Most other times, English was the language of choice. This fact supports his parents’ and tutor's claim that English was his overall dominant language.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Benjamin's French and English utterances

2.1.2 The interlocutors

Besides his time at the daycare centre, three interlocutors had a relevant role in Benjamin's speech: his father, his mother and the tutor. His father (Kevin) is American and a native speaker of English. He was a science teacher in a local high school. His proficiency in French was at a novice-low level and he seldom used it, though he encouraged Benjamin to speak French with his tutor:

(1) ‘I speak mostly English with him. Uh, once in a while, I'll throw words out in French or short little phrases and a question’.

(2) Benjamin: Hi!

Kevin: En français, oui? [In French, yes?]

Benjamin's mother (Beth) is also American and a native speaker of English. Her first language is English but because of her professional background and her near-native knowledge of French, she had decided to raise Benjamin with French in order to increase his future opportunities and to introduce him to a global understanding of cultural diversity.

Benjamin's tutor, referred to as Marie, taught him French in an educational, yet relaxed atmosphere in his home one hour per week. The tutor is a French native and had been tutoring Benjamin for about two years prior to the study. Furthering Benjamin's French input and when in need of babysitters, Benjamin's parents only hired French-speaking babysitters, which included the tutor and the researcher.

2.1.3 The participant observer

I, a French native, was involved, not only in the data collection, but also in the interactions with Benjamin during the tutoring sessions with Marie. The initial goal for my presence was to collect data; however, Benjamin included me in several of his discussions and games.

2.2 Settings

The data for this study were mostly collected in the home of Benjamin, and more particularly in the living room and kitchen. Some of the observations (not videotaped) were done at the daycare centre that Benjamin attended five days a week, in order to verify his parents’ claim that Benjamin did not use French when interacting with his classmates and teachers.

2.3 Data collection

The data was drawn from recorded observations (video-recordings and notes) and interviews collected over a period of about 3 months (age: 4;1 to 4;4). In most similar studies, researchers use recorded observations, interviews, and parents’ journal entries to record data. In this particular study, since the goal was not to analyse the child's speech over a period of time, but rather to observe the code-switching habits in particular situations, recorded observations and interviews were the chosen instruments. Observations in different settings and with different interlocutors were conducted, and interviews of the parents and the French tutor were collected to fully understand the child's language choice.

Ten hours and twenty minutes of data were collected, paralleled with field notes (15 typed pages). The observations took place at different settings and with different interlocutors (Table 2). The majority of the observations (seven hours) were done at the home of Benjamin's family, which was the most relevant setting, as it represented his true bilingual environment. Among those seven hours, two were with Benjamin and his mother only (the mother installed the camera that recorded them), of which one hour was during breakfast, with learning and playing opportunities; while the other hour was during a baking, learning and homework period. The five remaining hours were among Benjamin, Marie and the researcher (the researcher took care of the camera) during tutoring sessions. Non-video-taped observations (3 hours 20 minutes) were done at the daycare centre in order to observe his behaviur in a different linguistic environment and testify that his sole language was English. In addition, to better understand the subject's use of his two languages and to get personal opinions and anecdotes, Benjamin's parents and Marie were interviewed for approximately 30 to 40 minutes each. The interviews occurred prior to the observation of Benjamin and were semi-structured: a set of questions had been planned in advance, yet many of the questions during the interviews were based on the preceding answers of the participants. This data was audio-recorded, transcribed and later put in parallel with the notes, observations and data analysis of the study in order to complement the researcher's examination.

Table 2. Description of the recorded and non-recorded sessions

2.4 Data analysis

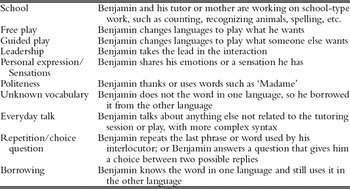

Seven hours of video-recordings of Benjamin at home were transcribed in their entirety by the researcher in order to examine each of Benjamin's language switches. The observations at the daycare centre were only supported by field notes, since the only language present was English, completed by the fact that the researcher did not seek authorisation from the parents of the children in Benjamin's class. In all the transcripts, the goals and the roles of Benjamin's interjections were identified following categories of previous research (Fantini, Reference Fantini1985; McClure, Reference McClure and Durán1981; Titone, Reference Titone1987). However, after studying the transcripts, the list was not complete enough, as some of Benjamin's speech could not be comprised in any of the categories. Therefore, additional or more focused categories had to be used in order to classify the data more appropriately: tutoring/school (Benjamin and his tutor or mother were working on school-type work, such as counting, recognising animals, spelling, etc.), free play (Benjamin changed languages to play what he wanted), guided play (Benjamin changed languages to play what someone else wanted), leadership (Benjamin took the lead in the interaction), personal expression/sensation (Benjamin shared his emotions or a sensation he had), politeness (Benjamin thanked or used words such as ‘Madame’), unknown vocabulary (Benjamin did not know the word in one language, so he borrowed it from the other language), everyday talk (Benjamin talked about anything else not related to the tutoring session or play, with more complex syntax), repetition/choice question (Benjamin repeated the last phrase or word used by his interlocutor; or Benjamin answered a question that gives him a choice between two possible replies) and borrowing (Benjamin knew the word in one language and still used it in the other language) (Table 3). To determine the categories, a close analysis of the thematic reoccurrences guided the choice in using existing categories, or in creating new ones that were more appropriate to the situations. For example, since Benjamin was mostly in an educational setting, a category concerning tutoring or school had to be created, since many actions were based on that vocabulary. The emotional and polite aspects of Benjamin's speech were not represented in the literature, therefore those categories had to also be added.

Table 3. List of Benjamin's code-switching functions

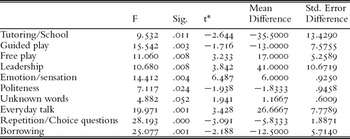

To strengthen the qualitative observations, the data was also quantitatively analysed, by counting each one of Benjamin's English and French episodes and comparing them through a statistical analysis. Table 1 gives the descriptive statistics, while Table 4 presents the results of an Independent T-test (alpha set at 0.05), allowing for stronger supporting evidence for the cases mentioned in this study. The T-Test was chosen to compare the significance of French and English use within each category. The results will be discussed along with the qualitative analyses in the next section.

Table 4. Independent samples test of Benjamin's French and English utterances

*Note: when t-value is positive, English provided for a greater number of utterances, while when t-value is negative, French provided for a greater number of utterances.

The field notes taken at the daycare centre and during the tutoring sessions provided additional support, with comments taken on the spot for a spontaneous understanding of Benjamin's recorded speech. They consisted of two columns: the left column contained the descriptions of events during the tutoring sessions, while the right one paralleled those descriptions by commenting and spontaneously reacting to what was observed. The field notes were subsequently compared with the transcript and analyses of the recordings.

As a note to the upcoming transcriptions, the following symbols were used to represent the discourse: [ ] for translation, ( ) for additional description of the situation, and N/A for incomprehensible. This study is clearly a small-scale study with only one subject involved in the analysis over a three-month period. This makes generalisation of the results limited, yet still valuable, as they can bring more evidence for understanding code-switching and language development among bilingual children, specifically in the situation of a non-native parent raising her child bilingually. Benjamin's bilingual environment is quite unusual, as only a few studies have examined it; furthermore, the angle of this study is very specific to functions of situational code-switching.

3 ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

Situational code-switching is defined as a shift of languages within the same speech exchange stimulated by the interlocutor, the setting or the topic shift surrounding the bilingual speaker (Gumperz & Hernandez-Chavez, Reference Gumperz, Hernandez-Chavez, Cazden, John and Hymes1972; McClure, Reference McClure and Saville-Troike1977; Titone, Reference Titone1987; Yumoto, Reference Yumoto1996). In this particular study, definite characteristics of situational code-switching were utilised by the bilingual child. Benjamin would change language depending on the person he was with, his location and the topic of his conversation. However, the focus of this paper is to primarily explore the functions of topic shift and roles; therefore the remainder of this article will analyse this particular variable in Benjamin's speech, which supported previous research as well as brought new perspectives to the use of code-switching.

3.1 Research question 1

The first question asked: can a child raised by a non-native parent produce situational code-switching triggered by specific topic change? Throughout the data, it was clear that Benjamin produced situational code-switching according to topic changes. Indeed, many previously-mentioned categories were observed in Benjamin's speech (Table 4). The categories of my data set illustrate some of characteristics previously mentioned by research, such as play and role play. Titone (Reference Titone1987) listed ‘showing off’ to explain social consideration or a change of contexts to emphasise. Fantini (Reference Fantini1985: 59) also presents categories for code-switching based on social situations: to exchange information, to shock, amuse, or surprise, to underscore, replicate, or emphasise. The forms code-switching can take are: ‘a) play; b) quoting, or citing a quotation; c) role play; d) story-telling; e) songs; f) jokes’. For Benjamin, English would be the language of choice when playing or pretending to be someone else (such as a pilot). Table 4 shows that English is significantly more frequent than French in the free play context (p = 0.008). The amount of English or French was also influenced by who was leading the play. When the tutor led the play, the use of French became significant (p = 0.003); while, when Benjamin was leading the game, his English took predominance. Cook-Gumperz (Reference Cook-Gumperz1985: 341) states that: ‘Children's games are arenas where children themselves are in charge of setting the pace and flow of their own communications. Games, particularly fantasy and pretend games, are social projects where children are spontaneously involved in self-organised settings and where speech is a naturally occurring part of the context’. These findings support other studies of bilingual children (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Hall and Kruth2002; Saunders, Reference Saunders1988), which showed that the person who was directing the play was the trigger for the language choice of the children.

Another common topic shift that reoccurred throughout the videos was tutoring/school. Once a week, Benjamin was taught to read and write in French by Marie who gave him a large amount of French input. He knew that French was the targeted language, as Marie was there to teach French. With his mother, he also did regular ‘homework’ in French to reinforce his learning. To explain this situation, Fantini (Reference Fantini1985) can be referenced for his mention of ‘role play’: the child imagines a mental situation of playing a role. For Benjamin, he put himself in the role of a French student. Therefore, his use of French became more frequent than in other situations, specifically when related to school activities at home, such as reading/saying letters, counting, recognising colours and animals. Table 4 supports this claim as it can be seen that French was significantly more frequent (p = 0.011) when the topic was schoolwork. This statement supports the previous literature (Fantini, Reference Fantini1985; Foster-Meloni, Reference Foster-Meloni1978), which points out the impact of a particular topic triggering one language over the other.

Benjamin also preferred English over French (p = 0.001) when he needed to talk about everyday life topics, such as his parents, his daycare activities, his friends, events that took place previously, toys, etc. The fact that Benjamin was raised by a non-native speaker of French, speaking French to him, does not seem to differentiate his behaviour from other bilingual children. He was aware of discussion topics and was able to link them with a specific language. He manipulated the situations with the languages he decided to use. Two other common changes that trigger a switch in the language are 1) leadership and 2) expression of emotions and sensations. These triggers are rarely mentioned in the literature and need deeper observations, such as those addressed in the second research question.

3.2 Research question 2

The second question asked: Are there new topics or roles to add to the previous literature that trigger a young English-French bilingual child to code-switch? With the data gathered, two more functions of code-switching emerged in Benjamin's speech: leadership and emotions/sensations.

3.2.1 Leadership

Leadership, in this context, is operationalised as the action of a person initiating a new situation or taking over the current situation. In this particular case, it also involves a linguistic shift from the part of the bilingual child, whenever he takes the lead of the situation. From the data, it is clear that Benjamin became or intended on becoming the leader of the situation, and he did so by using English. As Table 4 clearly shows, English is the language of choice for proclaiming that he was the person in charge (p = 0.008). Indeed, occasionally he readjusted the tutoring or teaching focus into a situation he decided upon. However, both his parents pointed out that on occasion, when he was alone, French was the language of choice. This could give even more support to the hypothesis that English was used for leadership. On his own, he did not need to employ any strategies of leadership to direct interactions. However, when he was with someone else who spoke French to him, he needed to show his presence by leading in the language of his choice: English. The following examples (3–10) clearly exemplify the case of code-switching for taking leadership and making his own decisions.

(3) Benjamin's mother is giving pieces of cereal, and Benjamin has to count them along with his mother. Beforehand, he decides on what needs to be done.

Beth: Tu vas compter avec moi? [You are going to count with me?]

Benjamin: Oui. [Yes]

Beth: Tu comptes? Je te donne huit. [You count? I give you eight of them]

Benjamin: Okay, but first, we need to spread them out.

(4) A little later, after breakfast is over, Benjamin and his mother decide whether to play chess. While deciding who will have which colour, Benjamin switches language to make sure he gets the colour he wants.

Beth: Tu joues aux échecs maintenant? C'est ça? [Do you want to play chess now? Is that it?]

Benjamin: We play échec. (pause) I am going to pick this one and you stay on the white.

Beth: Tu es le blanc et moi je suis le noir? [You are the white one and I am the black one ?]

Benjamin: No, I am the black and you are the red.

Beth: Oh, on joue aux dames maintenant. [Oh, we play checkers now.]

Benjamin: Yep, on joue aux dames. [Yep, we play checkers.]

(5) Benjamin and his mother are drawing their family. While describing what they are drawing, Benjamin switches to English to mention clearly what he will do.

Beth: Fais la tête, fais le corps, fais les jambes, fais les bras. [Do the head, do the body, do the legs, do the arms.]

Benjamin: Les yeux. [The eyes.]

Beth: Les yeux. [The eyes.]

Benjamin: I'll choose blue for the eyes.

(6) They are still drawing the family, and Benjamin does not want a specific crayon, and therefore, to control the situation, he uses English.

Beth: De quelle couleur sont tes cheveux? [What is the color of your hair ?]

Benjamin: Grises. [Gray.]

Beth: Tiens, tu peux utiliser le noir si tu veux. [Here, you can use the black one if you want.]

Benjamin: Nan, gris. [No, gray.]

Beth: Non, mais tu sais, pour faire gris, tu fais comme ça. Tu vois gris, c'est juste un peu de noir. Tiens, je vais faire les yeux de Papa. Laisse-moi faire les yeux de Papa. Voilà, tiens. [Non, but you know, to make gray, you can do like this. You see gray, it is just a little bit of black. Here, I will do Dad's eyes. Let me do Dad's eyes. Here, take it.]

Benjamin: I don't need it anymore.

(7) During an activity on animal recognition, Benjamin is instructing Marie to choose the big animals first, then the small ones.

Benjamin: Où est le chat? [Where is the cat?]

Marie: Le chat, il est ici. [The cat, it is here.]

Benjamin: Voilà! [Here it is!]

Marie: Okay, moi, je fais les petits animaux, ou c'est toi? [Okay, I do the small animals, or is it you?]

Benjamin: Me. Où est le chien? [Where is the dog?]

Marie: Ici. [Here.]

Benjamin: No, we are doing the little ones.

(8) The sun is shining in Benjamin's face so Marie offers to pull the shade down. Benjamin tells her not to do anything.

Marie: Est-ce que le soleil te dérange, Benjamin? [Does the sun bother you, Benjamin?]

Benjamin: Yeah!

Marie: Tu veux que je descende le store ou tu vas demander à Papa? [Do you want me to bring the blind down or will you ask Dad ?]

Benjamin: Don't do anything!

Marie: D'accord. [Okay.] Benjamin goes and gets his sunglasses

Benjamin: Comme ça! [Like this!]

(9) While working on a writing exercise, Benjamin changes the action.

Marie: Ok, maintenant, tu dois faire le ‘l’. Très bon! [Okay, now you need to do the ‘l’. Very good !]

Benjamin: Oh, d'accord, j'ai tout fait. [Oh, okay, I did everything.]

Marie: Qu'est-ce que tu fais? Allez, il reste à écrire un mot. [What are you doing? Come on, there is still a word to write.]

Benjamin: Let me see this! Benjamin is using a marker on a white board

Marie: Est-ce que c'est sec? [Is it dry?]

Benjamin: Oui, c'est très sec. [Yes, it is very dry.]

Marie: C'est très sec. Tu as besoin de tes lunettes maintenant? [It is very dry. Do you need your glasses now?]

Benjamin: I need something! He runs off the table to go grab his sunglasses.

(10) During another instance of writing exercise, Benjamin wants to do something else and attempts to change the course of the current action.

Marie: On doit écrire ‘le mouton’ et ‘la vache’. Où est-ce qu'ils sont ‘le mouton’ et ‘la vache’? [We need to write ‘the sheep’ and ‘the cow’. Where are the ‘sheep’ and ‘the cow’?]

Benjamin: We're going to do that and we're going to do that!

Marie: Mais non, pas encore! Regarde ici. Il faut écrire ‘le mouton’ et ‘la vache’. [No, not yet. Look here. You need to write ‘the sheep’ and ‘the cow’.]

Benjamin: La vache. [The cow.]

The examples show that each time Benjamin decided something or wanted to shift the direction of the interaction – as if to say ‘you were the leader, but now I am’ – English seemed to become the language of choice. The final sentence of example 11 clearly states his intent of leading.

(11) Benjamin, the tutor and the researcher are playing planes. Benjamin is giving directions.

Marie: Quoi? Les tickets? (French pronunciation of the word ‘tickets’) [What? The tickets?]

Benjamin: Yeah.

Marie: Voilà. [Here it is.]

Benjamin: This is in the . . .NA I am the boss!

As with the role of free versus guided play, this hypothesis can partially explain why the rate of English is much higher than French. Indeed, in both cases, the child was the one leading, either choosing the game or the activity to do, and consequently, deciding on the language. Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Hall and Kruth2002) had also discovered that a young bilingual child was able to distinguish between the leaders’ roles in a play context. In this present study, it also involves leadership in a school/tutoring context. Cook-Gumperz (Reference Cook-Gumperz1985) claims that children want to be in control of the situations they are in, and that their linguistic choice is influenced by that attitude. The pragmatic reason then becomes evident since the child manipulates the languages in order to manipulate the situation. This factor of leadership, specifically in a school or tutoring context, is a unique claim, as it has not been noted in this particular context of bilingualism. The social implications are important: a bilingual child appears to be able to choose one language over another in order to manipulate a new situation or redirect a discussion; he appears to be aware of possible social power contained in one of his language. The dynamic of the interaction can be changed just with a shift of language. This can also reflect the dominant language of the bilingual child, as they might require less effort taking the lead in the language in which they feel the most proficient.

3.2.2 Emotions/Sensations

This section offers another category that has rarely been noticed in the literature: the expression of emotion or sensation. For Benjamin, this factor seemed to trigger the dominance of one language over the other. Fantini (Reference Fantini1985) says that a child can code-switch in a ‘self-expression or private speech’. Benjamin's speech also showed examples of this, particularly based on emotions. Furthermore, Table 4 shows statistical significance in the preference of English over French (p = 0.004) when Benjamin had a need to express himself or share his emotions. In examples 12–15, Benjamin exclusively used English when he needed to communicate a deeper or more personal matter, even though the previous interactions with Marie were in French.

(12) Marie, Benjamin and the researcher are interacting. The researcher gives a marker to Benjamin. At the same time, Benjamin's father comes in the room to bring a cup of coffee to Marie. Benjamin reacts to the smell of the coffee.

Marie: Tu lui as dit merci? [Did you say thank you?]

Benjamin: Merci! [Thank you!]

Researcher: De rien! [You're welcome!]

Benjamin: Comment ça s'efface? [How do you erase it?]

Researcher: Il faut avoir une éponge ou il faut avoir un sopalin. [You need to have a sponge or you need a paper towel]

Benjamin: Ah. . .

Marie: Allez, écris ton nom et après on va écrire ‘w’ et ‘x’. Comment ça s'écrit ton nom? Moi, je me rappelle plus comment on écrit ton nom. [Go on, write your name, and then, we will write ‘w’ and ‘x’. How do your write your name? I don't remember how to write your name.]

Benjamin: You know?

Marie: Non, comment? [No, how?]

Benjamin: That coffee smells good!

(13) During a tutoring session with Marie, Benjamin has big toy toothbrushes he plays with and Marie brushes his hair. He really likes the feeling on his hair.

Marie: Voilà, comme ça. C'est très bien. [Here, like this. It is very good.]

Benjamin: Nan, comme ça, comme ça. [No, like this, like this.]

Marie: Comment? Comme ça? Ah, comme ça. Voilà. [How? Like this? Ah, like this. Here.]

Benjamin: Ah, that feels good!

(14) During a recognition activity, Marie and Benjamin work on animal names. Benjamin expresses his preference.

Marie: Alors, quel animal est-ce que tu vas colorier? Le canard? La chèvre? Le chien? Le chat? Ou le coq? [So, what animal will you color? The duck? The goat? The dog? The cat? Or the rooster?]

Benjamin: Le chat. [The cat.]

Marie: Le chat? Quelle couleur? [The cat? What color?]

Benjamin: It is my favourite.

(15) In this example, Benjamin is preparing some cupcakes with this mother. He is tasting the dry mix just poured into a bowl. He is eating and enjoying the small raspberries.

Benjamin: It tastes good, Mommy!

Beth: Qu'est-ce que c'est? [What is it ?]

Benjamin: These are good.

Beth: Qu'est-ce que c'est? [What is it ?]

Benjamin: Framboises. [Raspberries.]

These examples clearly illustrate the preferred language of his emotions or sensations. It is probable that since English had become his dominant language, Benjamin felt more comfortable and more satisfied expressing himself in it. The logical language of personal expression should be the language with which an individual is the most comfortable and, more likely, most proficient. Benjamin confirmed that English is the language with which he could communicate the deeper parts of his being. Most bilinguals or speakers of several languages will not argue that in most cases, emotions and sensations are best expressed in the dominant language. In Harding-Esch and Riley (Reference Harding-Esch and Riley2003), the mother of a child says that even though her husband and she are Turkish, English became the language for most communications with the child. Yet, she is still inclined to use Turkish in emotional situations, such as anger or haste. Genesee et al. (Reference Genesee, Paradis and Cargo2004) mentioned that a need to express oneself could cause language change. Benjamin's speech brings more support to this idea, and furthers it by presenting concrete examples of not only emotional expressions, but of physical sensations as well.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This study discussed the situational code-switching occurring within a young bilingual child's discourse, more specifically the factors of topic and roles in conversation. Two research questions were considered: Can a child raised by a non-native parent produce situational code-switching triggered by specific topic changes? Are there new topics or roles to add to the previous literature that trigger a young English-French bilingual child to code-switch? Supported by qualitative and quantitative data analyses, the answer to both questions is ‘yes’, as Benjamin showed clear evidence of situational code-switching when he initiated a change of topic. He was clearly aware of the appropriate language to use based on the topic of the situation. Being raised by a non-native speaker of French, Benjamin was still able to reach a recognised level of bilingualism and ease with his two languages, and followed the frequent practice of bilinguals. The social factor of leadership does not seem to concretely appear in empirical research, except in play activities (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Hall and Kruth2002); yet it was obvious that Benjamin was motivated by it in his language choice. In addition, there has been very little consideration of the expression of sensations and feelings in past studies. The personal and intimate connections one might have with a language might be a strong motivation for choosing one language over another. Benjamin showed his comprehension of the roles a language can have. When he decided to change the context of a situation or when he needed to share personal emotions, his preferred language was English. The social arenas of identity, power and transaction (Scotton & Ury, Reference Scotton and Ury1977) can explain Benjamin's attitude, as they were reflected in his language choice. He needed to develop his identity and the language he used helped him acquire more ‘power’ when he wanted to lead a situation or gave him importance in an interaction (or transaction). Language socialisation allows the individual, in this case Benjamin, to find a place and identity in his community (i.e., his home) (Ochs & Schieffelin, Reference Ochs, Schieffelin, Fletcher and MacWhinney1995).

As Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Hall and Kruth2002) noted, the understanding of bilingual children's communicative skills needs to be explored in greater depth; this present article furthered the knowledge of the factors stimulating the language choice of a child. It is clear that more research is needed to support the hypotheses presented in this study, and to verify if the categories employed in this study can indeed be applied to other children in a similar environment or in a one person-one language environment. Because behaviours can often be unpredictable, additional factors causing code-switching might be discovered, and should be reported to enable bilingual speakers a better understanding of their language choice.