1. Introduction

This article presents some new results exploring the fine-grained patterns of syntactic variation found in the endangered Gallo-Romance languages spoken in France. It presents another application of the methodology of the SyMiLa project (https://blogs.univ-tlse2.fr/symila/), one of whose aims is to exploit understudied syntactic data in the Atlas Linguistique de la France (ALF) (Edmont and Gilliéron, Reference Edmont and Gilliéron1910) for the construction of formal linguistic theory (see Dagnac, Reference Dagnac2018, for a description of this research program). The main proposal in this article is that data from the ALF can shed light on detailed morpho-syntactic properties of sentential negation in the Oïl dialects spoken in the North East of France, which have not yet been described.

In modern spoken French (for example, in the Parisian dialect), sentential negation is typically expressed using a negative adverb pas which can optionally co-occur with a preverbal particle ne (1).

(1)

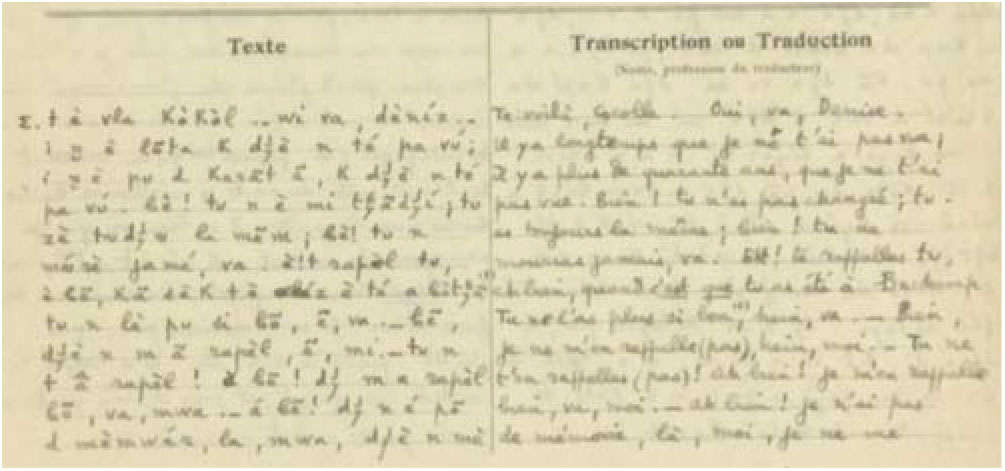

Given that negation systems vary significantly across the Oïl dialects,Footnote 1 we would like to know how the negation systems of the dialects spoken in the North East of France (along the border of France and Belgium) fit into this picture. As with most of the Oïl dialects, there has been very little study of the highly endangered languages spoken in this area, particularly of their morpho-syntactic patterns (although see Remacle, Reference Remacle1952; Tuaillon, Reference Tuaillon1975; Dagnac, Reference Dagnac2018). Some of the best data that we have for this area come from Brunot and Bruneau (Reference Brunot and Bruneau1912) and their 166 recordings of the patois spoken in the Ardennes mountains, which were made in June–July 1912 in the context of the Archives de la parole project. This study was the first French dialectological study to use both the phonograph and the automobile, and it produced both audio recordings (available at https://gallica.bnf.fr/html/und/enregistrements-sonores/archives-de-la-parole-ferdinand-brunot-1911-1914) and phonetic and French transcriptions such as the one shown in Figure 1 (available at https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k128002m).

Figure 1: Transcriptions of Fâcheuses aventures avec douaniers et garde-forestiers, collected by Brunot and Bruneau (Reference Brunot and Bruneau1912). Source: gallica.bnf.fr

The speaker in Figure 1 tells a story about how she was smuggling goods across the Belgian border and was stopped by customs guards. In the course of this short passage, she uses negative sentences with four realizations of sentential negation, shown in (2). (2-a) is the French model with ne…pas; (2-b) shows negation being expressed with the secondary negative adverb mie; in (2-c), the secondary negation is pont; and (2-d) shows no secondary negation at all in the phonetic transcription of the dialect (note that pas appears in parentheses in the French translation).

(2)

(2) shows that, in contrast to Parisian French, where all the negations would be expressed by ne…pas or just pas, sentential negation in North Eastern dialects is both complex and involves variation. This variation give rise to a number of questions for a couple of different areas of Romance linguistics: First, from the perspective of formal syntactic typology, we would like to know which syntactic structures should be associated with (2-a)–(2-d) and to what extent those structures coincide with those found in other Romance languages/dialects. Second, from the perspective of language variation and change, we would like to know which linguistic and/or social factors condition the use of these different structures; in other words, what makes a speaker choose to use one of the structures in (2) over the others?

When we are studying languages with a robust number of speakers, we usually go about answering these questions by doing an in-depth grammaticality or felicity judgement study with speakers that have the relevant grammatical systems and/or looking at the distribution of these forms in a large sociolinguistically annotated corpus. Unfortunately, these avenues of inquiry are not possible for the variety currently under study. The Gallo-Romance languages are highly endangered and access to native speakers is currently very limited, particularly in the North of France. Furthermore, as far as I am aware, there are practically no usable corpora of naturalistic speech from this area; even Brunot and Bruneau (Reference Brunot and Bruneau1912)’s set of recordings is not very large and, at the time of writing, it is not easily downloadable or transcribed. This article argues that we can address these methodological challenges and provide at least partial answers to our syntactic and variation questions through data that is ‘hidden’ in the Atlas Linguistique de la France (Edmont and Gilliéron, Reference Edmont and Gilliéron1910). This article therefore provides further evidence of the potential of the ALF to contribute to research in formal syntax and language variation and change, and therefore of the importance of the SyMiLa project.

This article is laid out as follows: in section 2, I discuss the potential of treating the ALF as an oral corpus and the challenges associated with doing so. Then in section 3, I give a quantitative study of secondary negations in North Eastern dialects. I first present some areal properties of the negation systems, and then zoom in on a case study of the variable syntax of negation in a variety spoken in and around the Lorraine region. Finally, section 4 concludes with a discussion of the perspectives for this line of research for future discoveries concerning the syntactic patterns of the endangered and extinct Gallo-Romance dialects and languages.

2. The ALF as an oral corpus

From 1897–1901, Edmond Edmont, under the supervision of Jules Gilliéron, travelled around France interviewing dialect speakers. Edmont asked speakers in 639 locations all over France (and parts of Belgium, Switzerland and Italy) to translate thousands of French words into their local dialects (see Brun-Trigaud et al., Reference Brun-Trigaud, Le Dû and Le Berre2005, for more about the ALF). The translations, transcribed in Rousselot-Gilliéron phonetic notation, are represented on maps where the translations are geographically situated at the location of the speaker(s) on the map. The entire atlas is available for browsing at http://ligtdcge.imag.fr/cartodialect4/.

Edmont presented the speakers with a word or a sentence, which we will call a stimulus, and then recorded the response. Rather than trying to painstakingly get the translation that corresponded most closely to the French sentence, Edmont recorded what the speaker produced in the moment, what he calls, “l’inspiration, l’expression première de l’interrogé, une traduction de premier jet” (Notice de l’ALF, p.7). The ALF is most famous for its maps of individual lexical items, and, indeed, the vast majority of the dialectological work using this atlas focuses on lexical patterns and phonological patterns observed from pronunciations of lexical items (see, for example, Eckert, Reference Eckert1985, Temple, Reference Temple2000; Brun-Trigaud et al., Reference Brun-Trigaud, Le Dû and Le Berre2005; Goebl, Reference Goebl2003, among many others). However, Edmont also asked speakers to translate 181 full sentences. Thus, as observed by Dagnac (Reference Dagnac2018), these 181 sentences hold great potential for syntactic data.

Of course, only a small portion of these 181 sentential stimuli are negative: 22 to be exact. These French stimuli are shown in Table 1, along with the maps on which the French negative expressions occur. Since it is not feasible to display whole translated sentences for 639 points on a single map, many of the 181 sentences were cut up into smaller expressions that were the topic of their own maps. In the context of the SyMiLa project, the full 181 sentential stimuli were reconstructed by Guylaine Brun-Trigaud, who was a collaborator on this project (see http://symila.univ-tlse2.fr/alf).

Table 1. Negative stimuli in the Atlas Linguistique de la France

With 22 negative stimuli and 639 points, there could be, in principle, up to 14,058 negative productions in the ALF. In reality, there are significantly fewer negative translations. This is because a fair number of stimuli, such as Personne ne me croit, Je n’ai pas osé le lui dire and N’aie pas peur are not translated by all speakers. Additionally, some stimuli are not translated as negative by some speakers. For example, this is the case of Elle n’est plus entière ‘She/it was no longer whole’, which was translated as elle est cassée ‘she/it was broken’ by speaker 133 (Courcelles-sur-Blaise).

3. Secondary negations in North Eastern France

Because this area of France is particularly understudied, in this article, I will focus on what the negative stimuli in the ALF can tell us about the form and distribution of secondary negations in North Eastern France and bordering Belgium and Switzerland. In particular, we will look at the negative productions at points numbered 1–199, which cover French territory in Lorraine Romane, Champagne, Bourgogne and Alsace. This dataset is composed of data from 150 points and contains 2989 negative productions. The ALF points covered in this study are shown on the map in Figure 2, which was created using the software QGIS (QGIS Development Team, 2015).

Figure 2: Area covered by the present study (points 1–150)

Figure 3 shows a representation of the entire dataset according to the shape of the secondary negation. It was created by overlaying transparent symbols representing the secondary negations in the 22 negative stimuli, or as many as were translated at the particular point. Thus, very dark consistent shapes indicate very little variation in the data at those points.

Figure 3: Forms of secondary negation(s) in entire dataset (points 1–150)

From this map, we can see that there is a large amount of variation both within a single geographical area and across geographical areas, and that different secondary negations are clustered in different areas. For example, although the French form pas appears smattered throughout the whole dataset, undoubtedly due to the fact that the French stimuli feature pas, pas is the dominant variant in the southern part of the area, well represented in the centre of France and the west of Switzerland. The marker point and its variant pont (see Dagnac, Reference Dagnac2018) are also found across the territory. The South East also features some forms like pe and the reduced form p. The dominant variant in Belgium is nen, and large portions of the North Eastern French part of the relevant area favour mie.

Unfortunately, a corpus of dialect translations is not ideal for doing either formal morpho-syntax or sociolinguistics (see Cornips, Reference Cornips, Barbiers, Cornips and van der Kleij2002; Baiwir and Renders, Reference Baiwir and Renders2013, for more discussion). Corpus linguistics has not traditionally been the preferred methodology for most theoretical syntacticians, since the lack of judgements of ungrammaticality is problematic for precisely identifying which set of expressions of the language should be analysed. Likewise, the complex syntactic structures that often interest syntacticians tend to be rare in natural speech; therefore, in order to get enough data to study syntax, we often have to pool data from different speakers in the corpus, which could be problematic if these different speakers have different internal grammars (Barbiers, Reference Barbiers2009). In the ALF, speakers of different dialects from different regions clearly have different grammars, so the question of how to meaningfully group speakers together to study them arises. In order to address these challenges, I propose to group together speakers who behave the same way with respect to the grammatical phenomenon that is being studied. In this case, we will group together speakers whose grammars coincide in the expression of negation. More specifically, I will present a detailed case study of grammars of speakers who use only mie as secondary negationsFootnote 2 . The ALF points with mie-only speakers are shown in the map in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Points where the sole negation is mie

Dialect atlases are also challenging sources of data for sociolinguistic analysis. First, rather than the collection of naturalistic speech, the ALF corpus was obtained through translation tasks. Therefore, we expect to see a repetition effect, i.e. the standard construction will be translated literally into the local dialect (Cornips, Reference Cornips, Barbiers, Cornips and van der Kleij2002). Second, although the Notice of the ALF provides some social information about the speakers consulted at each point, much of this information is opaque. For example, some points in the ALF represent data from multiple speakers with different sociolinguistic profiles: point 132 (Poissons, Haute-Marne), for instance, represents translations from a 72-year-old vieillard and his 25-year-old seamstress grand-daughter, people who have very different sociolinguistic profiles (Chambers and Trudgill, Reference Chambers and Trudgill1998). Likewise, some of the information, such as occupation, is incomplete for some speakers. In order to address these challenges, I propose to analyse only data produced by single speakers, for whom we have age, gender and geographical location information. From the dataset above, this corresponds to points associated with 122 single speakers yielding 2434 negative productions. Furthermore, we will take the repetition effect into account when interpreting the data. In particular, since all the stimuli are in Parisian French, the repetition effect should render the translations closer to French. In other words, in the ALF data, we should find:

1. Higher rate of ne preservation than in naturalistic speech.

2. Higher rate of pas use (vs mie) than in naturalistic speech.

3. Higher rate of use of secondary negations than in naturalistic speech.

Since we do have recordings by Brunot and Bruneau (Reference Brunot and Bruneau1912) it should be possible to check how the ALF lines up with the language in them, if these recordings ever become more accessible for detailed research.

3.1 Areal properties

Before diving into the detailed study of mie grammars, we should take a moment to observe some grammatical properties of the whole area. First, as shown in Table 2, we see that, in this part of France, the use of a secondary negation is almost excluded when the sentence contains a negative indefinite.

Table 2. Negative concord in the ALF (North East)

In other words, negative concord is limited to a couple of examples of pas…ni…ni ‘neither…nor’, shown in Figure 5, and a few examples of pa me Footnote 3 ‘no more’. These results therefore suggest that negative concord is not a robust grammatical phenomenon in north-eastern Gallo-Romance dialects, or at least not as robust as it is on Occitan territory (see Dagnac, Reference Dagnac2018).

Figure 5: Submap of Je ne pouvais ni avancer ni reculer (map 0901)

Another source of variation in postverbal negation markers is the sentence with the de indefinite: Dans ce pays, il n’y a pas de source ‘In this land, there are no springs.’ As shown in Figure 6, the marker point is favoured across most of the territory, even in areas where the principal marker is mie. This result is perhaps not particularly surprising, given that many studies of Old/Middle French (Parisian dialect) have suggested that point was favoured in partitive constructions (Marchello-Nizia, Reference Marchello-Nizia1979; Martineau, Reference Martineau, Kawaguchi, Durand and Minegishi2009), and Bruneau (Reference Bruneau1949), and Remacle (Reference Remacle1952) reports that Wallon point is limited to partitive constructions. Although il n’y a pas de source is not technically a partitive construction, it is possible that its association with the de phrase causes it to favour the more quantificational point (see also Pollock, Reference Pollock1989, for a version of this claim for French).

We can oppose the map of the de phrase sentence (Figure 6) with one of all the other sentences, shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6: Secondary negations in Dans ce pays, il n’y a pas de source (map 0089)

Figure 7: Secondary negations in sentences without the de phrase

Some speakers in this area of the ALF have the same form for both sentential negation and de phrase quantification: for example, the speaker at point 3 uses pas for all negative sentences. Likewise, speaker 191 uses nen for everything, and speaker 169 does the same thing with point. Some speakers with variable systems use one of the variants for the de phrase sentence: for example, 109 varies between pas and point for sentential negation, while using point for the de phrase sentence. Finally, many speakers have a form that is distinct from any secondary negation for the de phrase sentence: The speaker at point 1 uses pas in other negative sentences, but point in the de phrase sentence; 77 uses mie for negative sentences and point for de phrase; 49 varies between mie and pas, but uses point with the negative de phrase; and 50 uses pas for negative sentences, but mie with the de phrase. This suggests that the structure of negation in the sentence with the de phrase distinct from other occurrences of secondary negation in the corpus. Because it behaves differently from other negative sentences in the corpus, we exclude the stimulus with the de phrase from our case study on mie grammars.

3.2 Case study: mie grammars

In the last portion of this article, we will take a closer ‘vertical’ look at one more or less cohesive group of speakers: those who only use mie. There are 19 speakers like this in our ALF subcorpus. They are four women and 15 men, with ages ranging from 20–70. One speaker is from Belgium, two are from Champagne, one is from Alsace and the remainder (15) are from Lorraine (recall Figure 4). Speakers in this area are almost categorical users of the preverbal ne (only 7/281 omissions), which suggests that ne still has negative semantics in this dialect (see Godard, Reference Godard, Corblin and de Swart2004). I therefore propose that, similar to Italian non, it occupies a negative phrase between CP and TP which, following Zanuttini (Reference Zanuttini1997), I call NegP1.

In order to investigate the syntax of the secondary negation mie, we will take advantage of the observation by researchers using the cartographic approach (Cinque, Reference Cinque1996, Reference Cinque1999; Zanuttini, Reference Zanuttini1997, among others) that we can use ordering with respect to adverbs to diagnose the syntactic position of secondary negation markers. Research in this tradition has shown that there exist rigid ordering relations between adverbs within the languages of the Romance family. For example, as discussed in (Zanuttini, Reference Zanuttini1997: 64), the Italian adverb già ‘already’ obligatorily precedes the adverb piu ‘no more’ (3-a), and, when we look at the neighbouring Romance language French, we see exactly the same ordering between the cognates déjà and plus (3-b).

(3)

Using adverb ordering as a diagnostic, Cinque and Zanuttini argue in favour of the existence of a syntactic position for a higher postverbal negation, which Zanuttini (Reference Zanuttini1997) calls NegP2. This position is occupied by negative expressions that precede già/déjà or ancora/encore ‘yet’ and their cognates. As shown in (4)–(6), this class includes Italian mica, Piedmontese pa and French pas.

(4)

(5)

(6)

Zanuttini (Reference Zanuttini1997) argues in favour of a second postverbal negation position, which she calls NegP3, which is occupied by expressions that follow già/déjà or ancora/encore and their cognates. As shown in (7), this class includes Piedmontese nen, among other elements.

(7)

The ALF contains one stimulus with French encore: Mais l’avoine n’est pas encore mûre. Additionally, speaker 154 gives a translation of mais il ne vaut pas le mien using the adverb kor. Therefore, in our corpus, we have 20 productions with negation and the adverb (en)cor(e). The position of mie with respect to the adverb in these productions in shown in Table 3, and the relevant region of the map for this sentence is shown in Figure 8.

Table 3. Position of mie in sentences with (en)core

Figure 8: Partial submap from the ALF of -m (en)core mie (map 0899)

Although non-clitic mie largely follows (en)core, suggesting it is in NegP3 position, what is most striking in Table 3 and Figure 8 is the frequent encliticization of mie. This pattern has been observed in the Atlas Linguistique de la Champagne et de la Brie (ALCB) (Bourcelot, Reference Bourcelot1966), where it is described as follows: mie becomes a reduced clitic -m when the finite verb ends in a vowel. We know that -m forms a cluster with the finite verb because it is not separated from it by any expression in our data, and it even appears higher than the class of highest postverbal adverbs, which include donc ‘so’ (Cinque, Reference Cinque1996; Zanuttini, Reference Zanuttini1997). This can be seen in map 1409, which translates the relevant part of Tu ne vois donc pas que tu es aussi vieux que moi ‘So don’t you see that you are as old as I am’. As shown in Figure 9, enclitic mie precedes donc; whereas, the non-cliticized version follows it.

Figure 9: Partial submap from the ALF of vois donc pas (map 1409)

Although it is described as obligatory in the ALCB, encliticization appears to be optional in the ALF, as shown by two productions by speaker 154, both in the context of ako ‘yet’ (8).

(8)

Contrary to what is reported in the ALCB, not only is encliticization optional, but speakers also vary in their rates of cliticization. Table 4 shows that some speakers never cliticize; whereas, for some, the rate of cliticization is as high as 73%Footnote 4 .

Table 4. Rate of cliticization for mie only speakers in the ALF

Given that, as shown in Table 3, when mie is not cliticized, it mostly follows (en)core, I propose that it is located in the NegP2 position, following Zanuttini, although, for speaker 154, it may vary with the NegP3 position. Thus, the dominant syntactic structure for sentential negation is shown in (9), with mie raising to T in encliticization.

(9)

3.2.1 Mie drop

Although all the speakers in the ALF use secondary negation at least some of the time, mie can optionally be omitted, as shown in the examples in (10) from speaker 173.

(10)

Examples of variation in the omission (or ‘drop’) of mie are shown in Figure 10, where speakers 86 and 78 preserve the mie, but speakers 68 and 87 drop it in the translation of the stimulus on ne peut pas dormir.

Figure 10: Partial submap from the ALF of on ne peut pas (map 1083)

Given that mie can sometimes appear as a clitic, it is tempting to attribute ‘mie drop’ solely to the weak phonological status of this clitic -m. While it is probable that the clitic’s reduced phonological status plays a role in its deletion, an argument that the phenomenon also has a syntactic aspect comes from the fact that the mie drop process is, in fact, syntactically restricted in the ALF. In particular, much like the infrequent occurrences of sentences with bare ne in French (Muller, Reference Muller1991; Godard, Reference Godard, Corblin and de Swart2004), the absence of the secondary negation is limited to utterances composed of a modal verb such as pouvoir or savoir when it selects an infinitive, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Mie drop in mie-only grammars

The optionality of mie drop and its syntactic restriction raises questions about its source (is it structural or social?) and its nature (why do we find this syntactic restriction?). In order to contribute to answering these questions, I ran statistical analyses to determine whether factors related to syntactic structure (like the mie encliticization rate in Table 4) and social factors (speaker age and gender in the ALF Notice, and their administrative location) condition the presence or absence of mie. More specifically, I built generalized linear mixed effects models in R (R Core Team, 2016) with a logit function, using the lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2016), with the ALF point (N = 19) as a random effect and age (continuous), gender (m/f), location (Lorraine/Alsace, Champagne-Ardennes or Belgium) and mie cliticization rate as fixed effects. The linguistic factor (cliticization) and the three social factors (age, gender and location) were the only sociolinguistic factors available, given the sparseness of the data. The Notice sometimes provides more social information, such as profession, but this is not given for all speakers in the sample. The results of the statistical analyses (fixed effects) are shown in Table 6. We can see from this table that none of the social factors were significant.

Table 6. Results of statistical analyses (fixed effects). Intercept: Female speaker from Belgium

The main result from Table 6 is that the higher the rate of mie cliticization across all sentences, the less likely speakers will pronounce mie in biclausal sentences. In other words, the more likely a speaker is to cliticize mie onto the finite verb, the more likely they will simply omit it with an infinitive (11). The relationship between mie cliticization and mie drop is shown in Table 7.

(11)

Table 7. Relation between mie cliticization and drop

Why do we find speakers who favour mie encliticization also favour mie drop? Since mie drop is limited to a very particular syntactic context (modal verbs selecting infinitival constructions), a reasonable hypothesis is that there is something about the structure of the embedded non-finite clause that is blocking mie cliticization onto the upper finite verb. Sadly the data from the ALF is still very limited, and, given the highly endangered status of the language, it will be very difficult to test different syntactic hypotheses in great detail. Nevertheless, I believe that a possible line of analysis lies in the relationship between the omission of the secondary negation and the phenomenon of clitic climbing. As shown in Figure 11, in contrast to regions covered by the ALF, clitic climbing in infinitival constructions is not generally blocked in North Eastern France: in the sentence Il faut les y mener deux fois par jours ‘One must bring them there two times per day’, the order is always faut les rather than les faut, which is an order attested in the centre of France.

Figure 11: Submap of Il faut les y (mener deux fois par jour) (map 0535)

Thus a possible hypothesis for the relationship between mie cliticization and mie drop would be the following: in biclausal sentences, mie can be generated either in the higher or in lower clause. If it is generated in the lower clause and cliticization does not apply, then mie surfaces in the lower clause. If, however, it is generated in the lower clause and cliticization applies, then, because of the ban on clitic climbing, mie is simply unpronounced. This being said, this hypothesis is certainly not the only one possible; indeed, as mentioned above, secondary negation pas can sometime drop with modal verbs in dialects that do not have negative enclitization. However, investigating this question further would require new fieldwork studies with the remaining dialect speakers, so I leave it to future work.

4. Conclusion

In this article, I argued that ‘hidden’ syntactic data from the Atlas Linguistique de la France can be used to investigate the syntactic structure of negation in endangered North Eastern Gallo-Romance dialects. I argued that, for speakers who only use mie, this expression is generated as a lower postverbal negation marker, similar to Piedmontese nen, although for some speakers, it may be variably generated as a higher postverbal negation marker (like Piedmontese pa). In this way, the structure of negation in North Eastern French Gallo-Romance dialects shows important similarities to the structure of negation to closely-related Italian dialects like Piedmontese. Finally, statistical analyses of quantitative patterns of mie cliticization and mie drop suggest that there is a relation between these two processes, although pinning down exactly what this relationship is would require deeper work with native speaker consultants. Nevertheless, given that the ALF data has revealed a number of complex qualitative and quantitative grammatical patterns, I believe it could be used in future studies to identify empirical phenomena that merit further study and to diagnose grammatical relationships between these phenomena. I therefore conclude, following Dagnac (Reference Dagnac2018), that it is an invaluable tool for the study of the syntax of endangered Romance languages of France.