1. INTRODUCTION

This analysis focuses on language change led by young people in Paris, which can be compared with that described in other European cities, notably London. The data for it were collected for the Multicultural London English/Multicultural Paris French project,Footnote 1 other results of which are reported in this volume. As well as grammar, the project investigated discourse/pragmatic innovations, phonological developments, attitudes to the features observed, and compared developments in young people's speech in the two capital cities. By analysing a variety of features, of which the in situ questions are one, we aimed to establish whether a new variety which is shared by young people of different origins – i.e. a multiethnolect – is emerging in Paris, as it has for example in London and other Northern European capitals. Due to socio-demographic and other differences between the two cities, the youth varieties studied appear to take a divergent course (Hornsby and Jones, Reference Hornsby, Jones, Jones and Hornsby2013). This paper focuses on a grammatical structure found in the colloquial French of young people in the banlieues of Paris, using both a qualitative and quantitative approach. We hope this will contribute to a better understanding of language change in complex urban environments, paying particular attention to the role of bilingual speakers who belong to major communities of immigrant origin.

Contrary to the dictates of le bon usage (Sanders, Reference Sanders1993), some speakers use a structure in which the question word is placed at the end of embedded (or indirect) questions. This is found principally following savoir as the main verb, but also with other verbs of cognition such as connaître, comprendre, voir, oublier.

(1) Tu sais on l'appelle comment?

(2) Je sais même pas c'est où.

(3) On comprend direct c'est quel personage.

While the use of in situ indirect questions is one of the most striking grammatical features found in our Paris corpus, other grammatical features which we observed included:

a) Variations in relative clauses, e.g. que instead of dont (e.g. la fille que vous parlez); while far from being an innovation as such (Guiraud, Reference Guiraud1966), it remains unacceptable in bon usage and constitutes a possible simplification consistent with other features discussed here.

b) Changes of category: e.g. the vernacular adjective ‘de ouf’ (from ‘de fou’ = crazy, extreme) used as an adverb (e.g. on est sociable de ouf). Other changes in the form of adverbs may be ascribed to a similar category change, or simply to shortening (normal, direct).

c) Simplification of plurals in –AL (e.g. normals, spécials).

d) Alteration of word order (e.g. juste on s'est battu, toujours il essaie, obligé tu le fais, les populaires garçons).

Some of these features have been around for some years (e.g. (a) and (c), mentioned in Gadet (Reference Gadet1992). Several of them can also be compared with features found in London (Cheshire et al., Reference Cheshire, Kerswill, Fox and Torgersen2011). They are typical of situations where speakers of different mother tongues interact, and a widely accepted explanation is that they are based on simplifications introduced by the first generation of migrants, for whom, in this case, French or English were second languages (Mufwene, Reference Mufwene2008). Almost all the features mentioned above, as well as the specific one considered here, as we will explain below, could be seen as simplifying grammatical changes, typical of high-contact areas (Trudgill, Reference Trudgill, Guy, Feagin, Schiffrin and Baugh1996). As Milroy (Reference Milroy1987) pointed out, network structures which characterise big cities are particularly conducive to change; these developments typically arise in the speech of young people of immigrant origin and then spread to other speakers. But although it is possible that more innovations arise in Paris than elsewhere in France, changes affecting the grammar remain exceptional even in the capital (Gadet, 2007). Consequently, studies of French urban youth vernaculars have tended to concentrate instead on lexical and phonological change (e.g. Jamin, Reference Jamin2005; Fagyal, Reference Fagyal2010; Billiez et al., 2013). The consensus so far is that there is little evidence of new-dialect formation extending to the grammar (Hornsby and Jones, Reference Hornsby, Jones, Jones and Hornsby2013).

The in situ embedded question form stands out in relation to much more numerous lexical and phonological features which are seen as typical of banlieue youths. In terms of lexis, there is evidence of the continuing creation of new verlanFootnote 2 terms (Lepoutre, 2001),Footnote 3 of lexical items which have entered French from the ‘langues d'origine’ including numerous Arabic and Romani words (see http://www.dictionnairedelazone.fr); and of new terms of address, such as ‘frère’, characteristic of multicultural youths. This contrasts with the situation for French more generally, where a major source of change is the borrowing of words from English, often with a shift in meaning or grammatical recategorisation.Footnote 4 Syntactic change based on influence from English is also limited.Footnote 5 There were however some instances in our data where speakers used an English verb without conjugating it, e.g. Je l'ai follow sur Twitter. This also applied to some verbs of English origin which have been assimilated for some time (e.g. je l'ai boycott) or verlanised (e.g. je l'ai ken = niqué, in the sense of battu).

Regarding phonological features, as in other European capitals, young people's speech shows evidence of simplification, levelling, and re-allocation of existing patterns (Fagyal, Reference Fagyal2010). The majority of these processes are not specifically associated with young people of immigrant origin and can be found in long-standing ‘Franco-French’ vernaculars as well (Fagyal, Reference Fagyal2004; Armstrong and Jamin, Reference Armstrong, Jamin and Salhi2002). One of the questions we will discuss is whether the grammatical feature studied here also has such antecedents rather than being an innovation in the strict sense. The embedded question structure is discussed in more detail in Section 2, but first here are two extracts from our data which illustrate the structure in the context of longer utterances:

(4) SAM:Footnote 6 moi par exemple si je me marie avec une chrétienne par exemple elle comparé à moi sa mère c'est une chrétienne son père c'est un musulman tu sais elle faisait quoi la mère? elle donnait du porc en scred à son enfant.

‘For example if I get married with a Christian for example she compared with me her mother she's a Christian her father is a Muslim you know she did what the mother? (lit.) She was giving pork in secret to her child’.

(5) AIM: qui ont (.) par exemple sur Facebook et tout ils ont des milliers d'amis mille cent amis jusqu'à (.) genre on peut aller jusqu'à quatre mille amis de toute façon à un moment Facebook il bloque parce qu'on peut plus avoir xxx [= rire] (..) des amis que tellement je sais plus c'était combien.

‘Who have (.) for example on Facebook and all they have thousands of friends a thousand a hundred friends up to (.) like you can go up to four thousand friends in any case at a (certain) moment Facebook gets stuck because you can't have (laughter) any more friends it was so many I don't know it was how many (lit.)’.

Other examples from the data, with où, qui, quoi, combien and quel/quelle include:

(6) Je sais pas il est où.

(7) Il savait pas c'était qui.

(8) Tu me dis pas c'est quoi.

(9) Je sais pas c'était combien.

(10) Je sais pas ils ont quel âge.

(11) Je sais plus c'est quelle place.

In Section 2 we describe the structure in more detail and comment on the place of this grammatical development within the type of language change we are considering here. In Section 3 we review some of the literature available regarding this type of structure in French and consider its possible sources. Section 4 details our methodology. The results of our analysis are described in Section 5, where we highlight the parameters of the use of this structure by young Parisian speakers. The discussion in Section 6 considers further the possible role of the factors discussed, including contact effects, language ideology, the relaxation of norms in multilingual friendship groups, covert prestige and tendencies towards topicalisation and focus affecting language change.

2. THE STRUCTURE

2.1 Question formation in context

Word order in direct questions has been widely studied in French (Coveney, Reference Coveney1996; Reference Coveney1997; 2002; Reference Coveney2011; 2012; Deprez et al., Reference Déprez, Syrett and Kawahara2013; Larrivée, Reference Larrivée2014) and in this context the use of in situ question words has a long history (Ayres-Bennett, Reference Ayres-Bennett2004: 50–58; Adli, Reference Adli2013). In particular, in colloquial questions, verb-pronoun inversion is scarcely found except in set phrases like ‘pouvez-vous me passer le sel?’, and instead the declarative order is preserved (pourquoi il vient?).

A common and equally colloquial alternative involves highlighting the question-word by placing it at the end:

- il vient pourquoi?Footnote 7 (Goosse, Reference Goosse, Antoine and Cerquiglini2000: 117; Quillard, Reference Quillard2001)

Embedded questions have not been the subject of research to nearly the same extent (though see Lefeuvre and Rossi-Gensane Reference Lefeuvre and Rossi-Gensane2017). Also, as Andersen and Hansen point out, in casual speech the dividing line between embedded and non-embedded questions is not always clear, owing to pauses and false starts (2000: 148).

2.2 Embedded questions

The traditional order in an embedded question has the question-word before the pronoun and verb, regardless of register or modality:

- Je sais pas combien c'était.

This contrasts with the ‘new’ variant, which involves placing the question-word after the verb:

- Je sais pas c'était combien.

This structure is identified as a grammatical change typical of urban youth in Gadet (Reference Gadet, Ammon, Dittmar, Mattheie and Trudgill2006: 1790), although data on its use is not provided. As we shall see, in other corpora collected in metropolitan France it can scarcely be found.

2.3 Questions with ‘What. .?’

a) Direct questions

‘What. .?’ questions differ from other wh- questions in French. Whereas other question-words (qui, quand) are the same both in questions and in statements, ‘what’ questions involve the question word qu'est-ce que or que instead of quoi. However contrast the more standard ‘Qu'est-ce que c'est?’ with informal (or emphatic) ‘C'est quoi?’.

The latter type of in situ question, described for example by Larrivée (Reference Larrivée2014), was most likely pragmatically marked to begin with, but its use has now progressed to being characteristic of the colloquial register (by contrast, the English equivalent ‘It's what?’ is only found as an echo question). As Larrivée points out, if you postulate that there is a pragmatic significance, then you need to explain what this could be; the most obvious one here is the highlighting of the last word in the sentence, which puts the focus emphatically on the object of the enquiry. Quillard (Reference Quillard2001) has argued that sociolinguistic (e.g. register-related) and pragmatic explanations interact and should be jointly investigated.

b) Indirect questions

In (conventional) indirect questions, ce que replaces the question word qu'est-ce que/ que:

- Je sais ce que c'est.

‘I know what it is’

In a number of varieties including regional French, vernacular and so-called ‘français populaire’,Footnote 8 the question word is left unchanged in embedded questions (Blanche-Benveniste, Reference Blanche-Benveniste1997):

- Je sais qu'est-ce que c'est.

‘I know what it is’

The qu'est-ce que form is stigmatised both in speech and in writing and is corrected by schoolteachers. However, this form has existed for a considerable amount of time, notably in non-European varieties such as Canadian French (Sankoff, Kemp and Cedergren, Reference Sankoff, Kemp, Cedergren, Shuy and Firsching1976; Kemp, Reference Kemp and Thibault1979) and regional varieties in France, e.g. in Picardie (Pooley, Reference Pooley1996). We excluded the qu'est-ce que type from our quantitative analysis, a) because it did not clearly fit in with the pre- and post-verb distinction which was our focus; its analysis is further complicated by the positional allomorphy of quoi and qu'est-ce que; and b) because there were hardly any tokens of this form in our corpus. Instead, we will be considering a third possible variant where the question word quoi is in situ (je sais c'est quoi).

2.2 Word order rules in French

Changes in word order are more unusual than some other types of language change and require complex explanations. Their exact path is often difficult to retrace (Posner, Reference Posner1997: 348). In French, word order was codified in the Early Modern Period, the undoing of Latin/vernacular diglossia having been completed early for French (Lodge, Reference Lodge1993). Changes in inversion rules have a particularly long and complex history (Posner, Reference Posner1997: 356–369). In modern French, topicalisation, dislocation, clefting and focus-marking sometimes mean that elements can be moved around, depending on a variety of operative factors. Non-inversion after fronted WH-question words is very common in colloquial usage (‘Quelle heure il est?’ instead of ‘Quelle heure est-il?’). It cannot be explained by topicalisation or focus-marking but rather by the cognitive ease of leaving the pronoun-verb order unchanged in questions. As such the in situ structure considered here could be considered a form of levelling between direct and indirect questions. But when non-inversion occurs in WH-in situ (direct) questions, such as ‘Tu as fait quoi?’ ‘Tu as acheté combien?’ – also very common in colloquial speech – focus-marking is also a possible motivation.

Again as regards direct questions, the flexibility within in situ questions has been described as ‘a unique empirical testing ground for an investigation of the factors governing variation among interrogatives within a language’ (Deprez et al., Reference Déprez, Syrett and Kawahara2013:5). Apparently equivalent surface forms are thought to have different implications regarding the presupposed context (Deprez et al., Reference Déprez, Syrett and Kawahara2013:5), e.g. the different ways of asking ‘Where are you going?’:

a) Où est-ce que tu vas?

b) Où vas-tu?

c) Où tu vas?

d) Tu vas où?

The distinctions in meaning between these are subtle and lengthy to explain. For example, as Deprez et al. (Reference Déprez, Syrett and Kawahara2013) point out, (d) above may be most natural when uttered in the course of a conversation about plans when a ‘going out’ event is clear from the context and the only information that remains unknown is the destination.

Apart from the question of information structure, discussion in the literature mainly addresses possible differences in the intonation contours associated with the different types of question (Cheng and Rooryk, Reference Cheng and Rooryk2000; Deprez et al., Reference Déprez, Syrett and Kawahara2013); and parameters of acquisition/use of the different forms by children, autistic subjects (Durlemann et al., Reference Durrleman, Marinis and Franck2016) or adult learners (Santiago et al. 2015). Certain clues as to the differences in meaning may be provided by intonation/prosodic contours. Unfortunately most of the literature on these issues does not address the case where the question is embedded within a subordinate clause. There is therefore a dearth of literature on the embedded structure, and such as there is often tends more towards the prescriptive than the descriptive. Defranq (Reference Defrancq, Andersen and Hansen2000: 136–137) for example, writing about ‘non-embedded’ indirect questions (‘sans enchâssement’), describes these throughout the article by the term ‘anomalies’. He quotes a suggestion by Blanche-Benveniste (Reference Blanche-Benveniste1997) that the use of ‘qu'est-ce que’ in embedded questions is due to a ‘refusal’ to use the ‘prescribed’ form ‘ce que’ – implying that speakers make a – sociolinguistically improbable – conscious binary choice between a ‘correct’ and an ‘incorrect’ alternative (2000: 134).

In the case of embedded questions, if sentences like d) were considered the default form, then we could simply assume that the order is being left unchanged when they are in a subordinate clause. The difficulty lies in identifying which is the default form – a concept which makes sense to linguists but whose relationship to the speakers’ thought processes is more problematic. Both in embedded and in direct contexts, focus-marking provides a plausible internal motivation for placing the question word at the end of the clause; but we need to have recourse to other factors and other types of analysis to explain why this form is not distributed evenly through the population.

3. MULTILINGUAL CITY CHANGE, CONTACT-BASED EXPLANATION OR INTERNAL CHANGE?

Next we will review the possible hypotheses which present themselves regarding the origins of the embedded in situ structure.

3.1 Multicultural city change

The first of these involves seeing it as a change typical of multicultural cities – even in the absence of a generalised multiethnolect. The common sources of change in multicultural cities such as London are summarised below.

a) Features which can be traced back to the L1 of the speakers’ parents (Sharma, Reference Sharma2011, Sharma and Sankaran, Reference Sharma and Sankaran2011).

b) Innovations picked up through communication in multiethnic friendship groups (Rampton, 1995/Reference Rampton2005; Pooley and Mostefai-Hampshire, Reference Pooley and Mostefai-Hampshire2012).

c) Simplifications typical of L2 speakers, which have long been thought to be common to other ‘reduced’ forms of natural language (Jakobson, Reference Jakobson1941).

d) The creation of new features from a multicultural ‘feature pool’ (Mufwene, Reference Mufwene2008) which then spread to so-called ‘monolingual’ varieties.

It is possible that more historically-based explanations, to do with the development of such features in French since the seventeenth century, are also relevant, but these are beyond the scope of the current article.

Cheshire et al. (Reference Cheshire, Kerswill, Fox and Torgersen2011) also point out that some features may be adopted precisely because they are foreign to the dominant language, and so represent a kind of linguistic rebellion. Once they are present in the ‘feature pool’ (Mufwene, Reference Mufwene2008), as Cheshire et al. (Reference Cheshire, Kerswill, Fox and Torgersen2011) also remark, we need to ask to what extent purely linguistic factors (e.g. frequency, regularity, transparency, salience) determine their spread or whether social factors and attitudes are more significant (Thomason, Reference Thomason2001: 77).

3.2 Contact-based explanation

From a cross-linguistic and diachronic perspective, Hopper and Traugott (Reference Hopper and Traugott2003: 63) observe that: ‘Of the factors involved in word order Footnote 9 change, by far the most important is language contact’. A contact-based explanation should therefore also be considered. Thomason and Kaufman (Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988) and Matras (Reference Matras2009) point to numerous cases where a minority pattern in language A becomes, over time, the majority pattern through contact with language B, where it is the dominant pattern. However, in this case, it is problematic to consider the new structure even as a minority pattern, at least in the context of Paris French. Point (a) above requires that the language origin of the structure be identified; but the most widely spoken immigrant varieties in this context, Maghrebi Arabic and Berber, do not, as far as we have been able to establish, provide an obvious model.Footnote 10 More indirect effects of contact – which does not always result in a direct calque from another language – are best discussed under other headings including the Feature Pool and simplification.

However, Ledegen's recent work suggests a possible origin in other varieties of French. In a study of French as spoken in the French Creole (or ‘semi-Creole’)-speaking territory of Réunion, near Mauritius, Ledegen found in her 2007 corpus the in situ structure to be as common as the pre-verb form (and incidentally much more common than the type with ‘qu'est-ce que’). It was most frequent among the young, and was not considered marked. Ledegen describes it as a feature of “grammaire première”– i.e. the grammar acquired by all speakers of the language, independent of education (Blanche-Benveniste, Reference Blanche-Benveniste1990) – which is later ‘evacuated’ by the learning of a second grammar at school (2007: 22). In a later study based on SMS data (2011), which casts further light on the processes involved, Ledegen notes the increasing tendency for young people in Réunion to mix French and Creole, and for Creole syntax, based on juxtaposition rather than explicit subordination, to merge with vernacular French grammar to the point where it can no longer be identified as ‘interference’ from Creole, though it may still be labelled thus by schoolteachers and purists (2011: 104).

Could it therefore be the case that speakers from Réunion based in Paris were responsible for the introduction of this variant? Unfortunately from the point of view of testing this hypothesis, the Réunnionais do not figure in the official statistics on immigration because Réunion is an ‘overseas department of France’, so we do not know how numerous they are in the relevant banlieues. From the figures which are available, we can deduce that Réunionnais are not particularly numerous: just over 100,000 in France overall, of whom 70% live in the Southern part (Abdouni and Fabre, Reference Abdouni and Fabre2012), leaving at most 30,000 in Paris. There are therefore too few Réunionnais to assert that this was a significant influence, though the feature may indeed have been present in the feature pool. Significantly, Ledegen (Reference Ledegen2016) invokes further French-speaking contexts where the in situ structure is common; these include Quebec (Lefebvre and Maisonneuve, 1982; see also Plunkett, Reference Plunkett, Alexandrovna and Amandova2001), New Caledonia and Belgium; others have also confirmed that it is attested in Québec French (Wim Remysen, p.c). These multiple sources lead Ledegen to invoke the lesser influence of the Metropolitan standard on French spoken outside France, along with general tendencies in the language to adopt a fixed word order and parallels between direct and indirect structures.

3.3 Internal change

Since these overseas varieties are unlikely to come into direct contact with banlieue French in Paris, a straightforward contact-based explanation is improbable. On the other hand, the fact that the structure is present in several colloquial varieties spoken outside France does not exclude more an internal motivation.Footnote 11

Thus a more modulated hypothesis is that both in Réunion and among our subjects, the contact situation encourages speakers to prioritise a word order that fits in with communicative pressures; this is more likely to occur when pressure to conform to prestige norms is weakened. As suggested above, a pragmatic motivation for the structure would be that putting the question word at the end of the sentence follows a trend in spoken language to highlight the most important information by placing it either in initial or in final position (Miller and Weinert, Reference Miller and Weinert1998: 195–196). Such pragmatic significance may of course weaken over time (Harris, Reference Harris1984). As mentioned, as regards simplification or levelling, it is cognitively easier to maintain the same word order in embedded questions as in colloquial direct ones (‘il a fait quoi ? – je sais pas il a fait quoi’). This is the explanation favoured by Lefeuvre and Rossi-Gensane (Reference Lefeuvre and Rossi-Gensane2017) in an extensive review of forms which embedded questions can take in France, including the in situ structure.

These various explanations need not be exclusive: the interaction between internal and external pressures is complex and may be cumulative. For example, Wiese (2013) has shown that in the speech of young people in Berlin, what appear to be broadly speaking contact phenomena, such as grammatical simplifications typical of second language speakers, dovetail with internal change in that they cover new meanings or distinguish new sociolects.

Prosodic factors also play a significant part in our understanding of how the structure arises. If there is evidence of a hesitation or pause between the main clause and the embedded one, this could imply that the embedded clause is not directly dependent on the main one, as in: ‘je ne sais pas. . . . . .il a dit quoi ?’ in which case ‘il a dit quoi ?’ would just be a ‘normal’ colloquial question. However, in this case, careful listening to all the relevant examples revealed no noticeable break between the clauses. There was also no rising intonation in the second part to suggest that a direct question was being asked, which would have been the case if there was a pause between the two clauses.

4. METHODOLOGY

In order to understand the distribution and spread of the in situ structure in Paris, we set out to identify the types of speakers most implicated in using it, as a way of pinpointing who are the innovators and the adopters of the new variants. All indirect questions (both pre- and post-verb variants) in the data were tagged and coded for linguistic and social factors likely to affect the use of this feature. We then focused on looking at how the new variant was distributed, using the most informative factors: age, gender, ethnicity and network score, to which we added the speakers’ degree of bilingualism. This involved classifying young people according to the ethnicity of their friendship group, i.e. the extent to which their friends are from different language backgrounds to their own (see Cheshire et al., 2008).

Age

• Group 1 (10–14 years)

• Group 2 (15–16 years)

• Group 3 (17–19 years)

Ethnicity

• Group 1 (both parents French)

• Group 2 (mixed heritage; parents of different ethnic origins)

• Group 3 (parents of immigrant origin, same ethnicity)

Diversity of friendship network

• Network score 1 = all friends same ethnicity as self

• Network score 2 = up to 20% of friends a different ethnicity from self

• Network score 3 = up to 40% of friends a different ethnicity from self

• Network score 4 = up to 60% of friends a different ethnicity from self

• Network score 5 = up to 80% of friends a different ethnicity from self

Self-assessed degree of bilingualism / languages spoken at home

• Group 1: Monolingual French

• Group 2: Passive bilinguals

• Group 3: Active bilinguals

Tables (1)–(3) outline the distribution of speakers retained for this study.

Table 1. Distribution of speakers across age and gender

Table 2. Ethnic origin of speakers’ parents

Table 3. Distribution of speakers across the type of friendship network

Lastly, for completeness, various relevant grammatical factors were also examined, although as we will see, the only notable factor in the results was length of the embedded question:

• Variant: 1- pre-verb, 2- post-verb / in situ (application value)

• Clause type: Q-in situ with quoi (je sais c'est quoi), C- pre-verb ce que (je sais ce que c'est), I-in situ question word other than quoi (je sais il est où), O- pre-verb question word other than quoi (je sais où il est)

• Question word quoi/ce que, qui, où, combien, comment, quel/quelle, pourquoi

• Grammatical Person: both main and subordinate clause

• Tense: both main and subordinate clause

• Polarity: negative/affirmative

• Matrix verb: savoir, voir, chercher, comprendre, connaître, demander, dire, entendre, expliquer, faire, indiquer, oublier, regarder, se souvenir.

• Length of embedded question in syllables,

e.g. Je sais pas c'est quoi: 2 syllables; Je sais plus comment il s'appelait: 6 syllables

5. RESULTS

5.1 Embedded structures in MPF

Table (4.1) and (4.2) show the distribution of the in situ (post-verb) variant in our corpus. Types A and B represent the traditional way of constructing embedded questions.Footnote 13 The qu'est-ce que structure which was excluded, as explained above, only provided seven tokens, so removing these brings the total number of tokens down to 159.

Table 4.1. Pre-verb forms

Table 4.2. Post-verb (in situ) forms

The most striking finding overall is the much higher number of tokens of the in situ variant than in other French corpora (see below). Second, Table 5 shows that the use of the in situ variant is strongly linked with the degree of bilingualism of the speaker. Active bilinguals use it 57% of the time, whereas monolingual French speakers use it only 7.9% of the time.

Table 5. Distribution of variants across languages spoken at home

χ2 = 29.4576, p-value = < 0.00001.

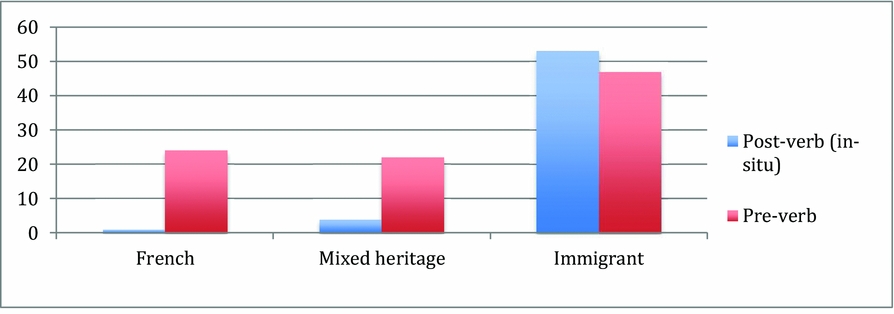

A similar picture is found with respect to ethnicity. Table 6 shows that the use of the in situ variant varies considerably according to ethnicity, with Group 3, whose parents are both of immigrant origin and of the same ethnicity, using it 53% of the time, whereas Group 1 (French parents) used it only 7% of the time.

Table 6. Distribution of variants across ethnic origin

χ2 = 28.2527, p-value = < 0.00001.

5.1.1 Gender

Table 7 shows males use the in situ variant twice as often as females. This fits in with the attested pattern whereby change which incorporates more vernacular variants is spearheaded by men. Women, it has been argued, tend to favour supralocal norms – though not necessarily standard ones: they favour standard forms in stable variation and innovative ones when change is in progress (‘The Gender Paradox’, see Trudgill, Reference Trudgill1972; Labov, Reference Labov1990). In this respect Paris is no different from many other cities where sociolinguistic change has been studied.

Table 7. Distribution of variants across gender

χ2 = 12.7017, p-value = .000365.

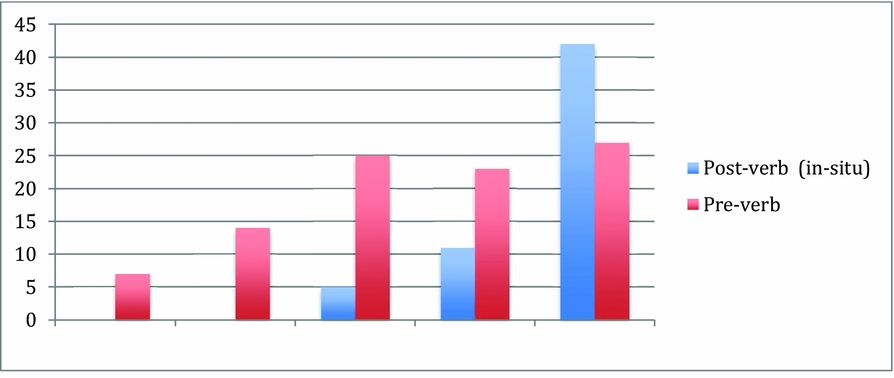

5.1.2 Network

Table 8 shows the relevance of having a multi-ethnic friendship group for the use of this new variant. In column 5 we see that speakers whose networks are made up of 80% of people with a different ethnicity to themselves use the in situ variant 60% of the time, whereas it is not present at all in Groups 1 and 2 where speakers’ friends are all (or almost all) of the same ethnicity as themselves. All but one of these is of local French origin (as defined by their parents’ origin), except for one in Group 2 who was half-Malgache.

Table 8. Distribution of variants across network score

χ2 = 34.662, p-value = < 0.00001.

As regards age, the highest users of the newer in situ variant are the youngest speakers. This seems likely to indicate a change in progress,Footnote 14 especially since the form appears to be so rare in adult speech (Branca et al., Reference Branca-Rosoff, Fleury, Lefeuvre and Pires2009). The structure scarcely arises in other corpora collected in France, as reported by Ledegen (Reference Ledegen2016: 95): ‘B. Defranq (Reference Defrancq, Andersen and Hansen2000) n'en atteste aucun exemple sur le corpus de 500 000 mots de CorpAix du GARS. Nous n'en trouvons aucun exemple non plus dans Le français ordinaire (Gadet, Reference Gadet1989) ou Le français populaire (1992); seulement une mention dans une étude des pratiques linguistiques des jeunes de la banlieue parisienne (Conein et Gadet, Reference Conein, Gadet, Androutsopoulos and Schotz1998)’. There were also very sparse instances in the Phonologie du français contemporain corpus (http://www.projet-pfc.net/), of which some were from Quebec speakers.

5.2 Multivariate analysis

5.2.1 Methodology and coding

Considering syntactic features as variables is a controversial issue within variationist sociolinguistics. In this case, however, there were two clear alternative forms for indirect questions: a) indirect questions with canonical order where the question word is placed pre-verb (e.g. je sais ce que c'est, je vois qui c'est), and b) indirect questions where the question word is placed in situ / post-verb (e.g. je sais c'est quoi, je vois c'est qui). Variable phenomena of this type have commonly been examined using logistic regression analyses in order to assess the weight of different social and linguistic factors on the use of a given variant (Labov, 1972, 1980; Guy, 1993: 237; Tagliamonte and D'Arcy, 2004; Cheshire et al., Reference Cheshire, Kerswill, Fox and Torgersen2011; Fox, 2012; Pichler and Levey, 2011). We therefore analysed our data using mixed-effect logistic regression in Rbrul (Johnson 2009).

As mentioned above, the factors considered were:

• Degree of bilingualism (1- monolingual, 2- passive bilingual, 3- active bilingual)

• Ethnicity (1- French / 2- Mixed heritage / 3- Both parents born outside France)

• Diversity of friendship network: 1 to 5 (5 most ethnically diverse)

• Gender

• Age (analysed as a continuous variable)

• Linguistic factors, as listed above

5.2.2 Analysis

In order to decide which factors should be included in the multivariate analysis, it is necessary to establish whether they are independent of one another. Cross-tabulations showed that the degree of bilingualism and ethnicity were highly correlated (i.e. active bilinguals were likely to come from immigrant families); therefore only ethnicity was included as a relevant factor. Further cross-tabulations showed that friendship network and ethnicity were also correlated, as we saw in a previous table, adapted in the graphs below.

Figure 1. Three types of embedded question in Reunion (adapted from Ledegen Reference Ledegen, Abécassis and Ledegen2007: 8)

Figures 2 and 3 show that the speakers of immigrant descent (group 3) are the most frequent users of the in situ variant, and similarly, the higher the network score, the more likely it is that the speakers will use the in situ variant (i.e. speakers with network score 5 are the most frequent users). To avoid interaction, the factors of ethnicity and network score were analysed in two separate runs of logistic regression.

Figure 2. Distribution of variants across ethnic origin

Figure 3. Distribution of variants across friendship network (from (1) – least diverse to (5) – most diverse)

Table 9. Distribution of variants across age

χ2 = 18.3955, p-value = .000101.

To further highlight the correlation of ethnicity and network score, Table 10 lists the most frequent users of the in situ form in a descending order (speakers who used 3 or more tokens, i.e. more than the overall mean of all users = 2.23). Of these speakers, two, Aissata and Gabin, who were both speakers with very diverse networks and bilingual parents, were categorical users of the in situ form in all the embedded questions which they produced.

Table 10. Most frequent users of the in situ formFootnote 15

Table 11 shows the results of the multivariate analysis of embedded questions, with the in situ form as application value.

Table 11. Contribution of factors to the probability of use of the in-situ variant

As we see, the in situ variant is strongly favoured by speakers from immigrant backgrounds. Since their parents are of the same ethnic origin and both born outside France, these speakers are also more likely to be exposed to foreign languages at home. This reinforces the hypothesis in Section 3, (a) that the use of this form is related to – if not solely caused by – contact with learner varieties spoken by their parents, whether or not it is ascribable to actual interference from the parents’ mother tongue. This is independent from the fact that at least in direct questions, the in situ form has been around for hundreds of years in certain varieties of French.

The second most important factor contributing to the likelihood of use of the in situ form is gender. The in situ form is favoured by male and disfavoured by female speakers. The in situ form is, in fact, the only variable that displays significant gender differences in the quantitative analyses of the MPF corpus. It is important to note that if we compare grammatical with discourse-pragmatic innovations (see Secova, Reference Secova2017 for general extenders and Cheshire and Secova, this volume, for quotatives), we find that they do not pattern in the same way. While innovative discourse features overall are used more often by female speakers, gender was not significant for individual variants. Information about the complexity of gender differences in the use of youth varieties is now beginning to emerge (Nortier, Reference Nortier2017). Some women in this study, while they are involved in changes affecting widespread discourse features, appear to avoid overtly stigmatised grammatical variants such as the in situ questions. However, the in situ form is popular with the most multicultural youths of both genders. This finding is borne out by the study of young people's linguistic attitudes carried out in a highly multicultural suburban secondary school in a northern banlieue of Paris (Secova, Gardner-Chloros and Atangana, this volume). In this, pupils were asked to comment on various alternative forms illustrating linguistic variation, including je sais ce que c'est and je sais c'est quoi. The pupils’ reaction to instances of the pre-verb form was negative; they dismissed it as being “too French”, and claimed that they did not use it (despite evidence to the contrary here). The in situ form, on the other hand, was described as quicker and easier to say (‘ça passe mieux’).

The friendship network, which was analysed separately from ethnicity, was also significant. As pointed out earlier, the higher the network score, the more likely it is that the speaker will use the in situ variant (the log-odds of +1.091 represent a positive relationship, with a 75% greater likelihood that a speaker with a more diverse network will use the in situ form).

The most significant demographic results therefore show the structure to be mainly used by speakers of immigrant descent, with an ethnically diverse friendship network, and to be favoured by males; these findings are discussed further below.

Of the grammatical factors which were investigated, the only significant one was the length of the subordinate clause in syllables (e.g. two syllables in je sais pas c'est qui). The longer the subordinate clause, the less likely it is that the in situ form would be used.Footnote 17 In other words, this variant is preferred with short clauses, such as c'est quoi, c'est qui or c'est où. Converting log-odds into percentages, the in situ variant is 25% less likely to occur with longer subordinate clauses. This may be linked to linguistic economy and cognitive processing in spontaneous speech, where there is a tendency towards shortening and simplification; the shorter phrases are also more likely to become entrenched as fixed phrases, owing to their frequency. Nevertheless, if the structure continues to spread, one could expect it to be used increasingly with subordinate clauses of any length.

The following instances from the data show some longer phrases following the question word.

12) lui tu sais on l'appelle comment ? (.) l'homme sans talent [= name] (.) aucun talent rien.

13) tu sais ça me rappelle quoi de grailler Footnote 18 comme ça ?

14) il a redoublé la sixième et t'sais il avait combien en sixième ? (.) il avait douze [= laughter].

15) par exemple moi j'ai ramené (.) t(u) sais j'ai ramené combien de mots là-bas ?

Although there is a dearth of data from people from different social backgrounds and areas in the Paris region, we compared our results with the Corpus de Français Parlé Parisien (CFPP), collected mainly in more central areas of the city and involving generally older, more middle-class speakers (Branca-Rosoff et al., Reference Blanche-Benveniste, Antoine and Cerquiglini2000). In the light of the patterns reported above, it is not surprising to find that in the CFPP corpus there were only two instances of this structure, both used by male speakers of Moroccan origin (Branca and Lefeuvre, Reference Branca-Rosoff, Lefeuvre, Avanzi, Béguelin and Diémoz2016). Similarly, Branca et al. (Reference Branca, Lefeuvre and Rossi-Gensane2015) note that in the Enquêtes Sociolinguistiques à Orléans (ESLO corpus, collected between 1968–1974 and from 2008) there were only three examples of the in situ form (eslo.huma-num.fr) though it is worth pointing out that this shows the form has a presence outside Paris. The authors further note that this form is still marginal in France, but its recent spread may be attributed to both grammatical motivations (alignment of direct and indirect in situ questions and a tendency towards parataxis) and social factors (the influence of peripheral / contact varieties on French in France due to recent immigration). The lack of instances found in such corpora is probably connected to the fact that their data does not focus on the varieties where this structure is likely to be found.

6. DISCUSSION: SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES

The majority of features held to be characteristic of urban youth vernaculars in Paris are either lexical (e.g. verlan) or phonological (e.g. pharyngeal r). The use of in situ question words in embedded or indirect questions is therefore exceptional – though not unique – in that it is a potentially wide-ranging change concerning grammar and word order, which has been reported in other French-speaking contexts but so far has been scarcely present in corpora collected in France (except in Strasbourg – see below). This variant represents a stigmatised departure from the variety of French promulgated at school and in other public fora. In the light of innovations found in other large cities, however, the emergence of in situ question words in embedded contexts as such is not surprising. As in other cities with high levels of immigration described in the literature, the young people studied in Paris acquired French from speakers who spoke many different languages, including both learner varieties of French and varieties such as Algerian French or Creole.

In this article, we are anxious to distinguish the origins of the structure from its spread and significance. We have seen that the structure's origins are likely to lie in a combination of internal and external motives, as has been observed with similar developments elsewhere (Wiese, Reference Wiese2009). Internal motivations include the pragmatic one of highlighting the question word by placing it at the end of the sentence, and the cognitively simpler mechanism of keeping the order of direct questions the same in embedded ones. It might also represent a case of functional levelling between older form of in situ questions (qu'est-ce que for ce que) and newer post-verbal structures (je vois c'est quoi): in both cases the direct question is ‘transplanted’ into an embedded one – though the low rate of use of the qu'est-ce que variant in our corpus does not lend any support to this hypothesis.

The alternative, contact-based explanation relies on the fact that the structure has (a) been attested – albeit rarely so far – in other vernacular varieties of French and (b) is common in at least one creole variety, spoken by immigrants from Réunion in Paris. We were unable to assert a creole origin for this form in Paris, first, because there were too few creole speakers in our sample, and second, because the heaviest users were young men of North-African origin. However the innovators and the heaviest users need not be one and the same. The most striking results concern the use of this stigmatised form by young highly networked North-African males, which we connect to the fact that the image and identity associated with Arabic speakers is tough and virile (Armstrong and Jamin, Reference Armstrong, Jamin and Salhi2002; Pooley and Mostefai-Hampshire, Reference Pooley and Mostefai-Hampshire2012). This is regardless of the low rate of transmission of Maghrebi Arabic as such.Footnote 19 The dense multiplex ties in the cités reinforce the strategic use of forms which may be frowned on by the establishment. There is now emerging evidence from elsewhere in France of similarly marginalised young people using the in situ construction as the default option, without showing any awareness of its negative social, educational or ethnic connotations (Marchessou, this volume). Taken together, these factors tip the balance less towards the influence of contact or of learner varieties, and more to an internal change, common to many ethnicities; this was also the case for various features studied in London.

We should also ask why this grammatical change in the Paris context is (a) exceptional, and (b) apparently absent from the speech of young people with fewer multi-ethnic contacts. How is it that this stigmatised feature, which affects the highly totemic grammar of French, has pierced through in the absence of a more widespread multiethnolect as found in London and the other European capitals, and remains specific to certain types of speaker?

The answer is likely to be complex and may have to do with the fact that several converging influences come into play. Like other large metropolises, Paris is not homogeneous but includes both large-scale and smaller-scale environments which intersect in distinctive ways. Contrasting with the heavy ethnic mix found in central areas of London, e.g. in Hackney, Hornsby and Jones (Reference Hornsby, Jones, Jones and Hornsby2013) consider that the social isolation of the banlieues from the centre of Paris is one of the reasons why linguistic features do not percolate from one to the other. Change from below is thereby – almost literally – circumscribed. In more general terms, Hornsby and Jones argue that good transport communications between French cities far apart from one another have promoted the emergence of supra-national norms (Jamin et al., Reference Jamin, Trimaille and Gasquet-Cyrus2006). But in this particular instance, the fact that the same structure has now been found among similar speakers in Strasbourg (Marchessou, this volume) is more likely the result of internal developments arising in similar contexts.

In both cases, the speakers in the cités who do use the in situ form operate in an environment where they may in fact have limited awareness that their behaviour is in any sense transgressing norms (Armstrong and Jamin, Reference Armstrong, Jamin and Salhi2002). This does not contradict attitudinal findings mentioned above regarding speakers’ dislike of forms that were ‘too French’, because despite what has just been said, multicultural youths living in the cités do not constitute a homogeneous whole. In some speakers, the use of youth vernaculars does not exclude proficiency in a more prestigious variety of French (Armstrong and Pooley, Reference Armstrong and Pooley2010: 268), and linguistic behaviour changes quite radically in pupils who reach the age of 16–17 and decide to continue with the last two years of (non-compulsory) schooling (Lepoutre, Reference Lepoutre1997; 2001: 423 ff). Such pupils become markedly more conformist at a linguistic as well as at other levels, a phenomenon which has not, to our knowledge, been observed in other comparable cities, where Contemporary Urban Vernacular (CUV)-type varieties may persist as stylistic or register variants well into middle age (Rampton, Reference Rampton2011; Sharma, Reference Sharma2011). This finding should be read in the light of Bourdieu's (Reference Bourdieu1984) comments on linguistic, cultural and related economic forms of capital, and their transmission via the educational system. Although it has been broadly applied in many other contexts, it is worth remembering that this notion of capital was originally developed in the French context, where education and linguistic/cultural ideology are particularly closely entwined. The speakers who use the in situ questions most frequently are a sub-group within a (geographically and culturally isolated) sub-group of Parisian youth and therefore probably the least amenable to such pressures. This type of social, ideological and geographical splintering is less evident, for example, in London, but it does not necessarily preclude the form from emerging in other locations outside Paris.

CONCLUSIONS

As Coveney (Reference Coveney, Jones and Hornsby2013: 80) remarks, ‘despite a considerable research effort into grammatical variation in metropolitan French, much still remains unknown’. We know from studies of language change in other diverse multiethnic settings that situations like that we studied in Paris can be significant catalysts for language change (Nortier and Dorleijn, Reference Nortier, Dorleijn, Bakker and Matras2013); however the evidence is so far lacking for the development of a comparable CUV in Paris. Although many of the relevant circumstances leading to their emergence elsewhere pertain there as well – a high degree of immigration and groups of second generation youths living side by side – the development studied here appears to be a relatively isolated phenomenon which does not fit into a broader pattern of multiethnolectal change.

One could of course object, as Gadet and Hambye point out (Reference Gadet, Hambye and Nicolai2014: 186), that varieties identified as CUVs are difficult to pinpoint partly because they are not consistently defined: sometimes they are seen in ‘ethnic’ terms (Türkendeutsch, Wallasprog), sometimes in territorial or neighbourhood-based terms (Kiezdeutsch, Rinkebysprog), and sometimes, somewhat euphemistically, in terms of age (langage des jeunes). This inconsistency partly reflects the emergent nature of the phenomenon; our findings about in situ indirect question structures are not in themselves out of line with developments elsewhere in terms of their origins (which as we saw could be both internal and external), or their main users (highly networked young males with strong ethnic connections). Within the cités, relative isolation from the rest of the city is reinforced by the fact that ties within them are generally dense and multiplex and so likely to reinforce the use of urban vernaculars.

In terms of future research, the speech of multicultural youths has yet to be systematically compared with that of their less multicultural French peers (Armstrong and Pooley, Reference Armstrong and Pooley2010: 267 – though for an exception see Pooley and Mostefai-Hampshire, Reference Pooley and Mostefai-Hampshire2012). What is clear from our analysis is that there are sharp divisions in the profile of those who use the structure; several further explanations for this could be explored, including that the in situ form is a marker for a particular type of male speaker (of a particular age and ethnicity); that it is used as a form of rejection of mainstream norms; or even that it is not a change in progress but an example of stable variation in which the non-mainstream variant is particularly favoured (as one would expect) by males. So whether it is or is not symptomatic of a putative CUV in Paris must remain an open question.

The study of in situ question words in embedded questions is less developed than that observed in direct questions, but the appearance of the former in our data parallels the increase observed in the latter. This grammatical change can be found in several varieties of French outside France, so the fact that it appears to be confined to a rather specific group of speakers within Paris is intriguing. At the same time, Marchessou (this volume) shows that it can be found in similar settings elsewhere in France; it therefore remains to be seen whether its geographical spread will be matched by social diffusion. Second, from the linguist's point of view, direct in situ questions in French have already been widely written about and the extension of such patterns to embedded questions – if that is indeed what we are witnessing – could provide valuable evidence on the development of such patterns within the language. Lastly, an interesting comparison could be made with verlan, which also inverts the traditional order of things and, one may guess, in so doing signals a form of rebellion against that order. Verlan makes speech more impenetrable to outsiders, but the in situ structure on the other hand is cognitively transparent, and perhaps only sounds topsy-turvy to normative ears. It remains to be confirmed whether it actually signposts a rebellious identity, or whether it is a more fluid and less conscious symptom of language change.