1 Introduction

Townsend (Reference Townsend1976) deduced that the energy-containing motions in the logarithmic region of wall-bounded turbulent flows can be understood as a linear superposition of self-similar eddies that are attached to the wall. The size of each eddy is proportional to the distance from the wall (![]() $y$). Townsend’s attached-eddy hypothesis predicts the turbulence statistics of the logarithmic region in terms of such structures, i.e. the logarithmic variation in the wall-parallel components of the Reynolds stresses. A typical feature of turbulent boundary layers (TBLs) subjected to adverse pressure gradients (APGs) is the enhancement in the large-scale energy above the logarithmic region. A strong outer peak is observed in the streamwise Reynolds stress, which results from long-wavelength motions in the energy spectra (Harun et al. Reference Harun, Monty, Mathis and Marusic2013; Kitsios et al. Reference Kitsios, Sekimoto, Atkinson, Sillero, Borrell, Gungor, Jiménez and Soria2017; Lee Reference Lee2017; Yoon, Hwang & Sung Reference Yoon, Hwang and Sung2018). The large-scale motions (LSMs) with sizes of

$y$). Townsend’s attached-eddy hypothesis predicts the turbulence statistics of the logarithmic region in terms of such structures, i.e. the logarithmic variation in the wall-parallel components of the Reynolds stresses. A typical feature of turbulent boundary layers (TBLs) subjected to adverse pressure gradients (APGs) is the enhancement in the large-scale energy above the logarithmic region. A strong outer peak is observed in the streamwise Reynolds stress, which results from long-wavelength motions in the energy spectra (Harun et al. Reference Harun, Monty, Mathis and Marusic2013; Kitsios et al. Reference Kitsios, Sekimoto, Atkinson, Sillero, Borrell, Gungor, Jiménez and Soria2017; Lee Reference Lee2017; Yoon, Hwang & Sung Reference Yoon, Hwang and Sung2018). The large-scale motions (LSMs) with sizes of ![]() $O(\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF})$ in the logarithmic region, where

$O(\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF})$ in the logarithmic region, where ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$ is the 99 % boundary layer thickness, influence the small-scale motions through amplitude modulation (Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007b; Bernardini & Pirozzoli Reference Bernardini and Pirozzoli2011; Agostini & Leschziner Reference Agostini and Leschziner2014; Hwang et al. Reference Hwang, Lee, Sung and Zaki2016b) and their footprints extend into the near-wall region (Hoyas & Jiménez Reference Hoyas and Jiménez2006; Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007a). Recently, Hwang & Sung (Reference Hwang and Sung2018) reported that the wall-attached structures of the streamwise velocity fluctuations (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$ is the 99 % boundary layer thickness, influence the small-scale motions through amplitude modulation (Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007b; Bernardini & Pirozzoli Reference Bernardini and Pirozzoli2011; Agostini & Leschziner Reference Agostini and Leschziner2014; Hwang et al. Reference Hwang, Lee, Sung and Zaki2016b) and their footprints extend into the near-wall region (Hoyas & Jiménez Reference Hoyas and Jiménez2006; Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007a). Recently, Hwang & Sung (Reference Hwang and Sung2018) reported that the wall-attached structures of the streamwise velocity fluctuations (![]() $u$) are self-similar and contribute to the presence of the logarithmic layer in a TBL of zero pressure gradient (ZPG). Therefore, research is required into the application of Townsend’s attached-eddy hypothesis to APG TBLs, particularly through analysis of the wall-attached

$u$) are self-similar and contribute to the presence of the logarithmic layer in a TBL of zero pressure gradient (ZPG). Therefore, research is required into the application of Townsend’s attached-eddy hypothesis to APG TBLs, particularly through analysis of the wall-attached ![]() $u$ structures in order to predict the influence on the turbulence statistics of strengthened LSMs. Although many studies of the turbulence statistics of APG TBLs have been performed, sufficient attention has not been paid to wall-attached structures despite their importance.

$u$ structures in order to predict the influence on the turbulence statistics of strengthened LSMs. Although many studies of the turbulence statistics of APG TBLs have been performed, sufficient attention has not been paid to wall-attached structures despite their importance.

The concept of attached eddies originates in the research of Townsend (Reference Townsend1976), who proposed a double-cone vortex model for the energy-containing motions with sizes that are proportional to ![]() $y$, i.e. those that are attached to the wall. The wall-attached structures are self-similar and are superimposed by eddies of various sizes with a constant characteristic velocity. In the logarithmic region, the Reynolds normal stresses can be characterized in the terms of Townsend’s attached-eddy hypothesis as follows:

$y$, i.e. those that are attached to the wall. The wall-attached structures are self-similar and are superimposed by eddies of various sizes with a constant characteristic velocity. In the logarithmic region, the Reynolds normal stresses can be characterized in the terms of Townsend’s attached-eddy hypothesis as follows:

In the last two decades, several studies of high-Reynolds-number wall-bounded turbulent flows (![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}>O(10^{4})$) have been performed owing to improvements in experimental equipment and computational power;

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}>O(10^{4})$) have been performed owing to improvements in experimental equipment and computational power; ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}$ is the friction Reynolds number (

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}$ is the friction Reynolds number (![]() $=u_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}$, where

$=u_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}$, where ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}$ is the kinematic viscosity). The influence of wall-attached structures is enhanced as the Reynolds number increases. For instance, logarithmic behaviour in

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}$ is the kinematic viscosity). The influence of wall-attached structures is enhanced as the Reynolds number increases. For instance, logarithmic behaviour in ![]() $\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$ has been observed in ZPG TBLs with

$\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$ has been observed in ZPG TBLs with ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=O(10^{4})$ (Hutchins et al. Reference Hutchins, Nickels, Marusic and Chong2009; Vallikivi, Hultmark & Smits Reference Vallikivi, Hultmark and Smits2015; Baidya et al. Reference Baidya, Philip, Hutchins, Monty and Marusic2017; Samie et al. Reference Samie, Marusic, Hutchins, Fu, Fan, Hultmark and Smits2018), an atmospheric surface layer with

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=O(10^{4})$ (Hutchins et al. Reference Hutchins, Nickels, Marusic and Chong2009; Vallikivi, Hultmark & Smits Reference Vallikivi, Hultmark and Smits2015; Baidya et al. Reference Baidya, Philip, Hutchins, Monty and Marusic2017; Samie et al. Reference Samie, Marusic, Hutchins, Fu, Fan, Hultmark and Smits2018), an atmospheric surface layer with ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=O(10^{6})$ (Hutchins et al. Reference Hutchins, Chauhan, Marusic, Monty and Klewicki2012), turbulent pipe flows with

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=O(10^{6})$ (Hutchins et al. Reference Hutchins, Chauhan, Marusic, Monty and Klewicki2012), turbulent pipe flows with ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=O(10^{4}{-}10^{5})$ (Hultmark et al. Reference Hultmark, Vallikivi, Bailey and Smits2012; Örlü et al. Reference Örlü, Fiorini, Segalini, Bellani, Talamelli and Alfredsson2017) and a turbulent channel flow with

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=O(10^{4}{-}10^{5})$ (Hultmark et al. Reference Hultmark, Vallikivi, Bailey and Smits2012; Örlü et al. Reference Örlü, Fiorini, Segalini, Bellani, Talamelli and Alfredsson2017) and a turbulent channel flow with ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=5200$ (Lee & Moser Reference Lee and Moser2015). The

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=5200$ (Lee & Moser Reference Lee and Moser2015). The ![]() $k_{x}^{-1}$ regions in the pre-multiplied energy spectra of

$k_{x}^{-1}$ regions in the pre-multiplied energy spectra of ![]() $u$ have been reported in ZPG TBLs with

$u$ have been reported in ZPG TBLs with ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=14\,000$ (Nickels et al. Reference Nickels, Marusic, Hafez and Chong2005), a turbulent channel flow with

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=14\,000$ (Nickels et al. Reference Nickels, Marusic, Hafez and Chong2005), a turbulent channel flow with ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=5200$ (Lee & Moser Reference Lee and Moser2015) and a turbulent pipe flow with

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=5200$ (Lee & Moser Reference Lee and Moser2015) and a turbulent pipe flow with ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=3008$ (Ahn et al. Reference Ahn, Lee, Lee, Kang and Sung2015). In addition, the

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=3008$ (Ahn et al. Reference Ahn, Lee, Lee, Kang and Sung2015). In addition, the ![]() $k_{z}^{-1}$ regions (where

$k_{z}^{-1}$ regions (where ![]() $k_{z}$ is the spanwise wavenumber) have been observed in ZPG TBLs with

$k_{z}$ is the spanwise wavenumber) have been observed in ZPG TBLs with ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=4000$ (Pirozzoli & Bernardini Reference Pirozzoli and Bernardini2013) and in turbulent channel and pipe flows (Ahn et al. Reference Ahn, Lee, Lee, Kang and Sung2015; Lee & Moser Reference Lee and Moser2015; Han et al. Reference Han, Hwang, Yoon, Ahn and Sung2019). A plateau in the pre-multiplied energy spectrum is not a necessary condition for logarithmic behaviour, since coherent motions contribute over a broad range of wavenumbers (Nickels & Marusic Reference Nickels and Marusic2001). Hwang (Reference Hwang2015) found that the spanwise wavelength (

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=4000$ (Pirozzoli & Bernardini Reference Pirozzoli and Bernardini2013) and in turbulent channel and pipe flows (Ahn et al. Reference Ahn, Lee, Lee, Kang and Sung2015; Lee & Moser Reference Lee and Moser2015; Han et al. Reference Han, Hwang, Yoon, Ahn and Sung2019). A plateau in the pre-multiplied energy spectrum is not a necessary condition for logarithmic behaviour, since coherent motions contribute over a broad range of wavenumbers (Nickels & Marusic Reference Nickels and Marusic2001). Hwang (Reference Hwang2015) found that the spanwise wavelength (![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}_{z}=2\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}/k_{z}$) of self-similar energy-containing motions is proportional to

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}_{z}=2\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}/k_{z}$) of self-similar energy-containing motions is proportional to ![]() $y$, which were isolated from the results of a filtered and over-damped large-eddy simulation (Hwang & Cossu Reference Hwang and Cossu2010; Hwang Reference Hwang2013). Hellström, Marusic & Smits (Reference Hellström, Marusic and Smits2016) showed that the azimuthal wavenumbers of energetic motions are inversely proportional to their wall-normal length scales by performing a proper orthogonal decomposition of results for pipe flows.

$y$, which were isolated from the results of a filtered and over-damped large-eddy simulation (Hwang & Cossu Reference Hwang and Cossu2010; Hwang Reference Hwang2013). Hellström, Marusic & Smits (Reference Hellström, Marusic and Smits2016) showed that the azimuthal wavenumbers of energetic motions are inversely proportional to their wall-normal length scales by performing a proper orthogonal decomposition of results for pipe flows.

Several models of such systems have been created by extending the model of Perry & Chong (Reference Perry and Chong1982) (Perry & Li Reference Perry and Li1990; Marusic, Uddin & Perry Reference Marusic, Uddin and Perry1997; Marusic Reference Marusic2001; Marusic & Kunkel Reference Marusic and Kunkel2003). Perry, Henbest & Chong (Reference Perry, Henbest and Chong1986) modified the inverse power law in the population density of attached eddies by increasing the weighting for those with ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$-height to accurately predict the velocity defect law and the energy distribution in the low-wavenumber region. Despite this modification for large scales (Perry et al. Reference Perry, Henbest and Chong1986), a significant difference arises between the experimental data and the model prediction for APG TBLs, especially for the Reynolds stresses in the outer region (Perry, Li & Marusic Reference Perry, Li and Marusic1988). In later research, several weighting functions have been employed to compensate for the velocity scales (Perry et al. Reference Perry, Li and Marusic1988) and to recover the geometrical similarity of eddies (Perry, Li & Marusic Reference Perry, Li and Marusic1991). Perry, Marusic & Li (Reference Perry, Marusic and Li1994) developed an analytical expression, based on the logarithmic law of the wall and the law of the wake (Coles Reference Coles1956), for the Reynolds shear stress

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$-height to accurately predict the velocity defect law and the energy distribution in the low-wavenumber region. Despite this modification for large scales (Perry et al. Reference Perry, Henbest and Chong1986), a significant difference arises between the experimental data and the model prediction for APG TBLs, especially for the Reynolds stresses in the outer region (Perry, Li & Marusic Reference Perry, Li and Marusic1988). In later research, several weighting functions have been employed to compensate for the velocity scales (Perry et al. Reference Perry, Li and Marusic1988) and to recover the geometrical similarity of eddies (Perry, Li & Marusic Reference Perry, Li and Marusic1991). Perry, Marusic & Li (Reference Perry, Marusic and Li1994) developed an analytical expression, based on the logarithmic law of the wall and the law of the wake (Coles Reference Coles1956), for the Reynolds shear stress ![]() $(\langle -uv\rangle )$ in APG TBLs by utilizing one eddy shape to formulate the relationship between

$(\langle -uv\rangle )$ in APG TBLs by utilizing one eddy shape to formulate the relationship between ![]() $\langle -uv\rangle$ and the mean defect velocity. Perry & Marusic (Reference Perry and Marusic1995) recognized that another eddy with a different shape is needed to describe Reynolds stresses in APG TBLs; the wall–wake attached-eddy model was proposed, comprised of wall-attached eddies (type A), larger detached eddies of size

$\langle -uv\rangle$ and the mean defect velocity. Perry & Marusic (Reference Perry and Marusic1995) recognized that another eddy with a different shape is needed to describe Reynolds stresses in APG TBLs; the wall–wake attached-eddy model was proposed, comprised of wall-attached eddies (type A), larger detached eddies of size ![]() $O(\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF})$ (type B) and smaller detached eddies including Kolmogorov scales (type C). Type B eddies with sizes that scale with their height mainly arise in the outer region and are modelled by trial and error. Perry, Marusic & Jones (Reference Perry, Marusic and Jones2002) extended the work of Perry et al. (Reference Perry, Marusic and Li1994) by including general non-equilibrium APG TBLs in the wall–wake attached-eddy model (Marusic & Perry Reference Marusic and Perry1995; Perry & Marusic Reference Perry and Marusic1995). A study of large scales in the outer region proposed a new approach to the analysis of larger detached structures (Smits, McKeon & Marusic Reference Smits, McKeon and Marusic2011). Details of the attached-eddy model are summarized in Marusic & Monty (Reference Marusic and Monty2019). Hwang & Sung (Reference Hwang and Sung2018) concluded that the wall-attached

$O(\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF})$ (type B) and smaller detached eddies including Kolmogorov scales (type C). Type B eddies with sizes that scale with their height mainly arise in the outer region and are modelled by trial and error. Perry, Marusic & Jones (Reference Perry, Marusic and Jones2002) extended the work of Perry et al. (Reference Perry, Marusic and Li1994) by including general non-equilibrium APG TBLs in the wall–wake attached-eddy model (Marusic & Perry Reference Marusic and Perry1995; Perry & Marusic Reference Perry and Marusic1995). A study of large scales in the outer region proposed a new approach to the analysis of larger detached structures (Smits, McKeon & Marusic Reference Smits, McKeon and Marusic2011). Details of the attached-eddy model are summarized in Marusic & Monty (Reference Marusic and Monty2019). Hwang & Sung (Reference Hwang and Sung2018) concluded that the wall-attached ![]() $u$ structures have an inverse power-law distribution and that there is an outer peak in their population density, which confirms that additional weighting is required for large scales as conjectured by Perry et al. (Reference Perry, Henbest and Chong1986). Hence, it is necessary to decompose coherent

$u$ structures have an inverse power-law distribution and that there is an outer peak in their population density, which confirms that additional weighting is required for large scales as conjectured by Perry et al. (Reference Perry, Henbest and Chong1986). Hence, it is necessary to decompose coherent ![]() $u$ structures from the perspective of attached-eddy models in order to understand the multiscale nature of wall turbulence.

$u$ structures from the perspective of attached-eddy models in order to understand the multiscale nature of wall turbulence.

Recently, increased attention has been paid to the coherent structures in APG TBLs. Hairpin packets are more inclined further from the wall (Lee & Sung Reference Lee and Sung2009; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Lee, Lee and Sung2010) and the inclination angle increases with increases in the strength of the APG (Lee Reference Lee2017). In the outer region, the lengths of the long ![]() $u$ streaks with size

$u$ streaks with size ![]() $O(\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF})$ decrease, and the widths of negative-

$O(\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF})$ decrease, and the widths of negative-![]() $u$ structures increase (Lee & Sung Reference Lee and Sung2009; Lee Reference Lee2017). It was difficult in the early studies to discriminate whether coherent structures are attached to the wall or detached. To overcome this limitation, intense coherent structures were extracted from instantaneous flow fields of isotropic turbulence (Moisy & Jiménez Reference Moisy and Jiménez2004), homogeneous shear turbulence (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Lozano-Durán, Sekimoto and Jiménez2017), ZPG TBLs (Sillero Reference Sillero2014; Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2018), turbulent channel flows (Del Álamo et al. Reference Del Álamo, Jiménez, Zandonade and Moser2006; Lozano-Durán, Flores & Jiménez Reference Lozano-Durán, Flores and Jiménez2012; Lozano-Durán & Jiménez Reference Lozano-Durán and Jiménez2014; Osawa & Jiménez Reference Osawa and Jiménez2018) and turbulent pipe flows (Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2019). The identified structures can be classified as wall-attached or wall-detached on the basis of their minimum distance from the wall. These wall-attached structures are self-similar and make dominant contributions to the turbulence statistics in the logarithmic region. Subsequently, Maciel, Gungor & Simens (Reference Maciel, Gungor and Simens2017a,Reference Maciel, Simens and Gungorb) analysed the individual clusters in non-equilibrium APG TBLs by identifying ejections and sweeps. The self-similar wall-attached ejections and sweeps in APG TBLs carry 30 %–45 % of

$u$ structures increase (Lee & Sung Reference Lee and Sung2009; Lee Reference Lee2017). It was difficult in the early studies to discriminate whether coherent structures are attached to the wall or detached. To overcome this limitation, intense coherent structures were extracted from instantaneous flow fields of isotropic turbulence (Moisy & Jiménez Reference Moisy and Jiménez2004), homogeneous shear turbulence (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Lozano-Durán, Sekimoto and Jiménez2017), ZPG TBLs (Sillero Reference Sillero2014; Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2018), turbulent channel flows (Del Álamo et al. Reference Del Álamo, Jiménez, Zandonade and Moser2006; Lozano-Durán, Flores & Jiménez Reference Lozano-Durán, Flores and Jiménez2012; Lozano-Durán & Jiménez Reference Lozano-Durán and Jiménez2014; Osawa & Jiménez Reference Osawa and Jiménez2018) and turbulent pipe flows (Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2019). The identified structures can be classified as wall-attached or wall-detached on the basis of their minimum distance from the wall. These wall-attached structures are self-similar and make dominant contributions to the turbulence statistics in the logarithmic region. Subsequently, Maciel, Gungor & Simens (Reference Maciel, Gungor and Simens2017a,Reference Maciel, Simens and Gungorb) analysed the individual clusters in non-equilibrium APG TBLs by identifying ejections and sweeps. The self-similar wall-attached ejections and sweeps in APG TBLs carry 30 %–45 % of ![]() $\langle -uv\rangle$ in the region

$\langle -uv\rangle$ in the region ![]() $y/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}=0.2{-}0.8$, which is larger than the contribution (25 %–40 %) for ZPG TBLs. The self-similar wall-detached ejections and sweeps mainly arise in the outer region, and their contribution to

$y/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}=0.2{-}0.8$, which is larger than the contribution (25 %–40 %) for ZPG TBLs. The self-similar wall-detached ejections and sweeps mainly arise in the outer region, and their contribution to ![]() $\langle -uv\rangle$ increases as the strength of the APG increases. Since self-similar structures in APG TBLs play a major role in their energy-containing motions, especially in the outer region, it is essential to analyse the coherent

$\langle -uv\rangle$ increases as the strength of the APG increases. Since self-similar structures in APG TBLs play a major role in their energy-containing motions, especially in the outer region, it is essential to analyse the coherent ![]() $u$ structures in APG TBLs by decomposing them in the terms defined by attached-eddy models.

$u$ structures in APG TBLs by decomposing them in the terms defined by attached-eddy models.

The objective of the present study is to explore the three-dimensional (3-D) ![]() $u$ clusters by decomposing them in the view of Townsend’s attached-eddy hypothesis. To this end, direct numerical simulation (DNS) data for APG and ZPG TBLs with

$u$ clusters by decomposing them in the view of Townsend’s attached-eddy hypothesis. To this end, direct numerical simulation (DNS) data for APG and ZPG TBLs with ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}\approx 800$ are used. The procedures for the identification of

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}\approx 800$ are used. The procedures for the identification of ![]() $u$ clusters are described in § 2. The identified structures are classified into attached self-similar (type A, wall scales), attached non-self-similar (type B, outer scales) and detached structures (viscous scales) according to their height (

$u$ clusters are described in § 2. The identified structures are classified into attached self-similar (type A, wall scales), attached non-self-similar (type B, outer scales) and detached structures (viscous scales) according to their height (![]() $l_{y}$). In § 3, we scrutinize the properties of type A and type B structures, which are both physically attached to the wall. The population densities of type A structures are inversely proportional to their height, and they are geometrically self-similar in APG and ZPG TBLs. Type B structures contribute to the presence of the outer peak located at

$l_{y}$). In § 3, we scrutinize the properties of type A and type B structures, which are both physically attached to the wall. The population densities of type A structures are inversely proportional to their height, and they are geometrically self-similar in APG and ZPG TBLs. Type B structures contribute to the presence of the outer peak located at ![]() $l_{y}=O(\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF})$ in the population density and are non-self-similar with

$l_{y}=O(\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF})$ in the population density and are non-self-similar with ![]() $l_{y}$. Type A structures are universal irrespective of the pressure gradient, whereas type B structures make dominant contributions to the outer large scales and are strengthened by the APG. In § 4, we explore the size distributions of the detached

$l_{y}$. Type A structures are universal irrespective of the pressure gradient, whereas type B structures make dominant contributions to the outer large scales and are strengthened by the APG. In § 4, we explore the size distributions of the detached ![]() $u$ structures, which can be classified as short or tall based on

$u$ structures, which can be classified as short or tall based on ![]() $l_{y}$. The former structures are non-self-similar, and the latter are isotropic and geometrically self-similar. Finally, we present our conclusions in § 5.

$l_{y}$. The former structures are non-self-similar, and the latter are isotropic and geometrically self-similar. Finally, we present our conclusions in § 5.

2 Numerical details

In the present study, the DNS dataset for an APG TBL (Yoon et al. Reference Yoon, Hwang and Sung2018) is used. The continuity equation and the Navier–Stokes equations for incompressible flows are discretized in this DNS by using the fractional step method (Park & Sung Reference Park and Sung1995; Kim, Baek & Sung Reference Kim, Baek and Sung2002; Kim, Huang & Sung Reference Kim, Huang and Sung2010). The computational domain sizes are ![]() $1834\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{0}\times 100\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{0}\times 130\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{0}$ in the streamwise (

$1834\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{0}\times 100\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{0}\times 130\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{0}$ in the streamwise (![]() $x$), wall-normal (

$x$), wall-normal (![]() $y$) and spanwise (

$y$) and spanwise (![]() $z$) directions, respectively. Here,

$z$) directions, respectively. Here, ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{0}$ is the inlet boundary layer thickness. The number of grids is 10 497 (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{0}$ is the inlet boundary layer thickness. The number of grids is 10 497 (![]() $x$)

$x$) ![]() $\times$ 541 (

$\times$ 541 (![]() $y$)

$y$) ![]() $\times$ 1025 (

$\times$ 1025 (![]() $z$). The power-law distribution of the free-stream velocity

$z$). The power-law distribution of the free-stream velocity ![]() $U_{\infty }=U_{0}(1-x/200\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{0})^{-0.2}$ is imposed on the Neumann boundary condition through the continuity

$U_{\infty }=U_{0}(1-x/200\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{0})^{-0.2}$ is imposed on the Neumann boundary condition through the continuity ![]() $(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\overset{{\sim}}{v}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}y=-\unicode[STIX]{x2202}U_{\infty }/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x)$ for an equilibrium layer (Townsend Reference Townsend1961; Mellor & Gibson Reference Mellor and Gibson1966). Here,

$(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\overset{{\sim}}{v}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}y=-\unicode[STIX]{x2202}U_{\infty }/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x)$ for an equilibrium layer (Townsend Reference Townsend1961; Mellor & Gibson Reference Mellor and Gibson1966). Here, ![]() $U_{0}$ is the inlet free-stream velocity and

$U_{0}$ is the inlet free-stream velocity and ![]() $\overset{{\sim}}{v}$ is the wall-normal component of raw velocities. For comparison, the DNS dataset for a ZPG TBL (Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2017) is also analysed. Details of the numerical procedure and the boundary conditions can be found in Yoon et al. (Reference Yoon, Hwang and Sung2018). The computational domain is summarized in table 1.

$\overset{{\sim}}{v}$ is the wall-normal component of raw velocities. For comparison, the DNS dataset for a ZPG TBL (Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2017) is also analysed. Details of the numerical procedure and the boundary conditions can be found in Yoon et al. (Reference Yoon, Hwang and Sung2018). The computational domain is summarized in table 1.

Table 1. Parameters of the computational domain. Parameters ![]() $L_{i}$ and

$L_{i}$ and ![]() $N_{i}$ are the domain size and the number of grids in each direction, respectively;

$N_{i}$ are the domain size and the number of grids in each direction, respectively; ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x0394}x^{+}$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x0394}x^{+}$, ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x0394}y^{+}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x0394}y^{+}$ and ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x0394}z^{+}$ are the grid resolutions in the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise directions, respectively; and

$\unicode[STIX]{x0394}z^{+}$ are the grid resolutions in the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise directions, respectively; and ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x0394}y_{min}^{+}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x0394}y_{min}^{+}$ and ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x0394}y_{100}^{+}$ represent the resolutions of the 1st and 100th wall-normal grid from the wall, respectively. The inner-normalized resolutions were obtained at

$\unicode[STIX]{x0394}y_{100}^{+}$ represent the resolutions of the 1st and 100th wall-normal grid from the wall, respectively. The inner-normalized resolutions were obtained at ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=775$ and

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=775$ and ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=825$ for the APG and ZPG TBLs, respectively.

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=825$ for the APG and ZPG TBLs, respectively.

The domain of interest (DoI) is ![]() $10\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}(x)\times 1.7\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}(y)\times 3\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}(z)$. Figure 1(a) shows the skin friction coefficient

$10\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}(x)\times 1.7\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}(y)\times 3\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}(z)$. Figure 1(a) shows the skin friction coefficient ![]() $(C_{f}=2u_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}^{2}/U_{\infty }^{2})$ and 3-D iso-surface of

$(C_{f}=2u_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}^{2}/U_{\infty }^{2})$ and 3-D iso-surface of ![]() $u$, where the colour contour indicates the DoI. The friction Reynolds numbers for the APG and ZPG TBLs are

$u$, where the colour contour indicates the DoI. The friction Reynolds numbers for the APG and ZPG TBLs are ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=775$ and 825, respectively, and the equivalent momentum-thickness Reynolds numbers are

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=775$ and 825, respectively, and the equivalent momentum-thickness Reynolds numbers are ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D703}}=4860$ and 2457, respectively (figure 1b). The variations in

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D703}}=4860$ and 2457, respectively (figure 1b). The variations in ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$ and momentum thickness

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$ and momentum thickness ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D703}$ are shown in figure 1(c). The defect shape factor,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D703}$ are shown in figure 1(c). The defect shape factor, ![]() $G\equiv \unicode[STIX]{x1D6E5}^{-1}\int _{0}^{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}}(U_{\infty }-\overline{U})^{2}u_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}^{-2}\,\text{d}y$, and the non-dimensional pressure gradient parameter,

$G\equiv \unicode[STIX]{x1D6E5}^{-1}\int _{0}^{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}}(U_{\infty }-\overline{U})^{2}u_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}^{-2}\,\text{d}y$, and the non-dimensional pressure gradient parameter, ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}\equiv \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}^{\ast }\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{w}^{-1}(\text{d}p/\text{d}x)=-\unicode[STIX]{x0394}u_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}^{-1}(\text{d}U_{\infty }/\text{d}x)$ (Clauser Reference Clauser1954), are almost constant (figure 1d). Here,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}\equiv \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}^{\ast }\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{w}^{-1}(\text{d}p/\text{d}x)=-\unicode[STIX]{x0394}u_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}^{-1}(\text{d}U_{\infty }/\text{d}x)$ (Clauser Reference Clauser1954), are almost constant (figure 1d). Here, ![]() $\overline{U}(y)$ is the streamwise mean velocity,

$\overline{U}(y)$ is the streamwise mean velocity, ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{w}$ is the wall shear stress,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{w}$ is the wall shear stress, ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}^{\text{*}}$ is the displacement thickness

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}^{\text{*}}$ is the displacement thickness ![]() $(\equiv \int _{0}^{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}}(U_{\infty }-\overline{U})U_{\infty }^{-1}\,\text{d}y)$ and

$(\equiv \int _{0}^{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}}(U_{\infty }-\overline{U})U_{\infty }^{-1}\,\text{d}y)$ and ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6E5}$ is the Rotta–Clauser length scale

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6E5}$ is the Rotta–Clauser length scale ![]() $(\equiv \int _{0}^{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}}(U_{\infty }-\overline{U})u_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}^{-1}\,\text{d}y)$. Note that

$(\equiv \int _{0}^{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}}(U_{\infty }-\overline{U})u_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}^{-1}\,\text{d}y)$. Note that ![]() $u_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}$ and

$u_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}$ and ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$ are chosen at the centre of the DoI. The characteristics of the DoI are listed in table 2.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$ are chosen at the centre of the DoI. The characteristics of the DoI are listed in table 2.

Figure 1. (a) Skin friction coefficient (![]() $\text{C}_{f}$) and 3-D iso-surface of

$\text{C}_{f}$) and 3-D iso-surface of ![]() $u$. The red line and the coloured contours indicate the DoI. (b) Momentum thickness Reynolds number (

$u$. The red line and the coloured contours indicate the DoI. (b) Momentum thickness Reynolds number (![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D703}}$) and friction Reynolds number (

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D703}}$) and friction Reynolds number (![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}$). (c) Momentum thickness (

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}$). (c) Momentum thickness (![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D703}$) and boundary layer thickness (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D703}$) and boundary layer thickness (![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$). (d) Defect shape factor (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$). (d) Defect shape factor (![]() $G$) and non-dimensional pressure gradient parameter (

$G$) and non-dimensional pressure gradient parameter (![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$). The points in (b) and (c) are representative of the DoI.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$). The points in (b) and (c) are representative of the DoI.

Table 2. The characteristics of the DoI. The numbers in parentheses indicate the values at the centre of the DoI (the points in figure 1b,c). Parameters ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{x}$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{x}$, ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{y}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{y}$ and ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{z}$ are the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise extents of the DoI, respectively.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{z}$ are the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise extents of the DoI, respectively.

2.1 Detection of the turbulent/non-turbulent interface

The turbulent/non-turbulent interface (TNTI) that demarcates the turbulent and non-turbulent regions can be defined based on kinetic energy criteria (Chauhan et al. Reference Chauhan, Philip, De Silva, Hutchins and Marusic2014). The purpose of this section is to introduce the contamination of velocity fluctuations by using the Reynolds decomposition near the TNTI. The accurate prediction of the TNTI is important for extracting wall-attached clusters in the outer region. The wall-normal height of the TNTI ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}(x,z,t)$ is varied depending on the boundary layer thickness

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}(x,z,t)$ is varied depending on the boundary layer thickness ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}(x)$. As a result, the structures of velocity fluctuations are contaminated near the TNTI (Kwon, Hutchins & Monty Reference Kwon, Hutchins and Monty2016). In particular, both large and small scales near the TNTI are significantly amplified in the APG TBL. The raw streamwise velocities (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}(x)$. As a result, the structures of velocity fluctuations are contaminated near the TNTI (Kwon, Hutchins & Monty Reference Kwon, Hutchins and Monty2016). In particular, both large and small scales near the TNTI are significantly amplified in the APG TBL. The raw streamwise velocities (![]() $\tilde{u}$) normalized by

$\tilde{u}$) normalized by ![]() $U_{\infty }$ are displayed in figure 2(ai), where the white line is the contour

$U_{\infty }$ are displayed in figure 2(ai), where the white line is the contour ![]() $\tilde{u} /U_{\infty }=0.95$. Figure 2(aii) shows the logarithm of the local kinetic energy (k) obtained from all velocity fluctuations in the reference frame moving with

$\tilde{u} /U_{\infty }=0.95$. Figure 2(aii) shows the logarithm of the local kinetic energy (k) obtained from all velocity fluctuations in the reference frame moving with ![]() $U_{\infty }$ over

$U_{\infty }$ over ![]() $3\times 3\times 3$ grids, and the black line in figure 2(aii) indicates the threshold value of

$3\times 3\times 3$ grids, and the black line in figure 2(aii) indicates the threshold value of ![]() $k$ chosen at

$k$ chosen at ![]() $k_{threshold}=0.2$, which corresponds closely to the line

$k_{threshold}=0.2$, which corresponds closely to the line ![]() $\tilde{u} /U_{\infty }=0.95$. The red line in figure 2(aiii) shows the TNTI determined from the black

$\tilde{u} /U_{\infty }=0.95$. The red line in figure 2(aiii) shows the TNTI determined from the black ![]() $k_{threshold}$ line. The mean height of the TNTI is

$k_{threshold}$ line. The mean height of the TNTI is ![]() $\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}\rangle =0.9\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$, which is slightly higher than that of a ZPG TBL

$\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}\rangle =0.9\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$, which is slightly higher than that of a ZPG TBL ![]() $(\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}\rangle =0.88\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF})$ (Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2018). The probability density function (PDF) of the TNTI (

$(\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}\rangle =0.88\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF})$ (Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2018). The probability density function (PDF) of the TNTI (![]() $P_{TNTI}$) and the intermittency (

$P_{TNTI}$) and the intermittency (![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FE}$) are shown in figure 2(b). Figure 2(c) shows magnified views of the rectangular box in figure 2(aiii) and thus illustrates how the TNTI is determined. In figure 2(c), the blue lines connect the points of the

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FE}$) are shown in figure 2(b). Figure 2(c) shows magnified views of the rectangular box in figure 2(aiii) and thus illustrates how the TNTI is determined. In figure 2(c), the blue lines connect the points of the ![]() $k_{threshold}$ grid including the turbulent region (

$k_{threshold}$ grid including the turbulent region (![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{T}$), and the green lines indicate the non-turbulent region (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{T}$), and the green lines indicate the non-turbulent region (![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{NT}$). Finally, to eliminate the turbulence drops in

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{NT}$). Finally, to eliminate the turbulence drops in ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{T}$ and the bubbles in

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{T}$ and the bubbles in ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{NT}$, we define the TNTI as the union

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{NT}$, we define the TNTI as the union ![]() $(\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{T}\cap \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{NT})$ (Borrell & Jiménez Reference Borrell and Jiménez2016; Yang, Hwang & Sung Reference Yang, Hwang and Sung2019).

$(\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{T}\cap \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{NT})$ (Borrell & Jiménez Reference Borrell and Jiménez2016; Yang, Hwang & Sung Reference Yang, Hwang and Sung2019).

Figure 2. (a) Iso-surfaces of (i) the streamwise velocity (![]() $\tilde{u}$), (ii) the local kinetic energy (k) and (iii) the TNTI in the

$\tilde{u}$), (ii) the local kinetic energy (k) and (iii) the TNTI in the ![]() $x$–

$x$–![]() $y$ plane. The black lines in (i) and (ii) indicate 0.95

$y$ plane. The black lines in (i) and (ii) indicate 0.95![]() $U_{\infty }$ and

$U_{\infty }$ and ![]() $k_{threshold}$ (

$k_{threshold}$ (![]() $=0.2$), and the red and black lines in (iii) and (c) are the TNTI and

$=0.2$), and the red and black lines in (iii) and (c) are the TNTI and ![]() $k_{threshold}$, respectively. (b) Intermittency (

$k_{threshold}$, respectively. (b) Intermittency (![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FE}$) and PDF of

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FE}$) and PDF of ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}$. (c) Enlarged views of the rectangular box in (aiii).

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}$. (c) Enlarged views of the rectangular box in (aiii).

All raw velocities (![]() $\tilde{u} _{i}$) are conditionally averaged with respect to the wall-normal height of the TNTI (

$\tilde{u} _{i}$) are conditionally averaged with respect to the wall-normal height of the TNTI (![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}$);

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}$); ![]() $\overset{{\sim}}{U}_{i}(y,\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI})$ (

$\overset{{\sim}}{U}_{i}(y,\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI})$ (![]() $=\langle \overset{{\sim}}{u}_{i}(\boldsymbol{x},t)|\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}(x,z,t)\rangle$) is the mean velocity as a function of

$=\langle \overset{{\sim}}{u}_{i}(\boldsymbol{x},t)|\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}(x,z,t)\rangle$) is the mean velocity as a function of ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}$ (Kwon et al. Reference Kwon, Hutchins and Monty2016). The mean velocity from the Reynolds decomposition is denoted as

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}$ (Kwon et al. Reference Kwon, Hutchins and Monty2016). The mean velocity from the Reynolds decomposition is denoted as ![]() $\overline{U}_{i}(y)$ (

$\overline{U}_{i}(y)$ (![]() $=\langle \overset{{\sim}}{u}_{i}(\boldsymbol{x},t)\rangle$). The velocity fluctuations can be defined in terms of

$=\langle \overset{{\sim}}{u}_{i}(\boldsymbol{x},t)\rangle$). The velocity fluctuations can be defined in terms of ![]() $\overset{{\sim}}{U}_{i}$ as

$\overset{{\sim}}{U}_{i}$ as ![]() $u_{i}(\boldsymbol{x},t,\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI})$ (

$u_{i}(\boldsymbol{x},t,\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI})$ (![]() $=\overset{{\sim}}{u}_{i}(\boldsymbol{x},t)-\overset{{\sim}}{U}_{i}(y,\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI})$) and from the Reynolds decomposition as

$=\overset{{\sim}}{u}_{i}(\boldsymbol{x},t)-\overset{{\sim}}{U}_{i}(y,\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI})$) and from the Reynolds decomposition as ![]() $u_{i}^{\prime }(\boldsymbol{x},t)$ (

$u_{i}^{\prime }(\boldsymbol{x},t)$ (![]() $=\overset{{\sim}}{u}_{i}(\boldsymbol{x},t)-\overline{U}_{i}(y)$). Note that Jiménez et al. (Reference Jiménez, Hoyas, Simens and Mizuno2010) obtained the TNTI based on enstrophy criteria. We found that the wall-attached structures remain qualitatively unchanged regardless of the detection method used. Figure 3(a) shows

$=\overset{{\sim}}{u}_{i}(\boldsymbol{x},t)-\overline{U}_{i}(y)$). Note that Jiménez et al. (Reference Jiménez, Hoyas, Simens and Mizuno2010) obtained the TNTI based on enstrophy criteria. We found that the wall-attached structures remain qualitatively unchanged regardless of the detection method used. Figure 3(a) shows ![]() $\overset{{\sim}}{U}$ and

$\overset{{\sim}}{U}$ and ![]() $\overline{U}$, where the profiles of

$\overline{U}$, where the profiles of ![]() $\overset{{\sim}}{U}$ diverge beyond

$\overset{{\sim}}{U}$ diverge beyond ![]() $y/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}=0.05$ and the magnitude of

$y/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}=0.05$ and the magnitude of ![]() $\overset{{\sim}}{U}$ at

$\overset{{\sim}}{U}$ at ![]() $y/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}=0.5$ decreases with increases in

$y/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}=0.5$ decreases with increases in ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}$. The streamwise Reynolds stress

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}$. The streamwise Reynolds stress ![]() $\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$ is calculated from

$\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$ is calculated from ![]() $u$ as shown in figure 3(b), where the two profiles of

$u$ as shown in figure 3(b), where the two profiles of ![]() $\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$ and

$\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$ and ![]() $\langle u^{\prime }u^{\prime }\rangle ^{+}$ coincide except near the boundary edge; the wall-normal locations of the outer peaks are independent of the pressure gradient. To highlight the discrepancy between

$\langle u^{\prime }u^{\prime }\rangle ^{+}$ coincide except near the boundary edge; the wall-normal locations of the outer peaks are independent of the pressure gradient. To highlight the discrepancy between ![]() $u$ and

$u$ and ![]() $u^{\prime }$, the instantaneous velocities of

$u^{\prime }$, the instantaneous velocities of ![]() $u$ (figure 3c) and

$u$ (figure 3c) and ![]() $u^{\prime }$ (figure 3d) are illustrated. The red and blue contours indicate positive and negative fluctuations, respectively. The solid line near

$u^{\prime }$ (figure 3d) are illustrated. The red and blue contours indicate positive and negative fluctuations, respectively. The solid line near ![]() $y$ =

$y$ = ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$ is a line contour of

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$ is a line contour of ![]() $k_{threshold}$. The magnitudes of the positive- and negative-

$k_{threshold}$. The magnitudes of the positive- and negative-![]() $u^{\prime }$ strengthen when

$u^{\prime }$ strengthen when ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}$ is lower than

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}$ is lower than ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$ (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$ (![]() $x/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$

$x/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$![]() ${\approx}$ 2 and 7.5) and higher than

${\approx}$ 2 and 7.5) and higher than ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$ (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$ (![]() $x/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$

$x/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$![]() ${\approx}$ 3.5 and 10), respectively.

${\approx}$ 3.5 and 10), respectively.

Figure 3. (a) Mean velocity ![]() $\overline{U}(y)$ and conditional mean velocity

$\overline{U}(y)$ and conditional mean velocity ![]() $\overset{{\sim}}{U}(y,\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI})$. (b) Profiles of

$\overset{{\sim}}{U}(y,\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI})$. (b) Profiles of ![]() $\langle u^{\prime }u^{\prime }\rangle ^{+}$ and

$\langle u^{\prime }u^{\prime }\rangle ^{+}$ and ![]() $\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$. Iso-surfaces of (c)

$\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$. Iso-surfaces of (c) ![]() $u$ and (d)

$u$ and (d) ![]() $u^{\prime }$. The black line indicates

$u^{\prime }$. The black line indicates ![]() $k_{threshold}$, and the red and blue contours indicate positive and negative fluctuations, respectively.

$k_{threshold}$, and the red and blue contours indicate positive and negative fluctuations, respectively.

2.2 Identification of coherent structures

The coherent structures of ![]() $u$ are defined as groups of connected points of

$u$ are defined as groups of connected points of ![]() $u(\boldsymbol{x},t)>\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}u_{rms}(y,\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI})$ and

$u(\boldsymbol{x},t)>\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}u_{rms}(y,\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI})$ and ![]() $u(\boldsymbol{x},t)<-\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}u_{rms}(y,\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI})$ in instantaneous flow fields, where

$u(\boldsymbol{x},t)<-\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}u_{rms}(y,\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI})$ in instantaneous flow fields, where ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$ is the threshold and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$ is the threshold and ![]() $u_{rms}$ is the root mean square of

$u_{rms}$ is the root mean square of ![]() $u$ as a function of

$u$ as a function of ![]() $y$ and

$y$ and ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}$. Note that the results shown in the present study are not sensitive to the variation of

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{TNTI}$. Note that the results shown in the present study are not sensitive to the variation of ![]() $k$ in the vicinity of

$k$ in the vicinity of ![]() $k_{threshold}$, because we extracted the intense turbulence motions (Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2018). To detect each

$k_{threshold}$, because we extracted the intense turbulence motions (Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2018). To detect each ![]() $u$ cluster, we use the connectivity of neighbouring six-orthogonal grids at a given node in Cartesian coordinates (Moisy & Jiménez Reference Moisy and Jiménez2004; Del Álamo et al. Reference Del Álamo, Jiménez, Zandonade and Moser2006; Lozano-Durán et al. Reference Lozano-Durán, Flores and Jiménez2012; Lozano-Durán & Jiménez Reference Lozano-Durán and Jiménez2014; Sillero Reference Sillero2014; Dong et al. Reference Dong, Lozano-Durán, Sekimoto and Jiménez2017; Maciel et al. Reference Maciel, Gungor and Simens2017a,Reference Maciel, Simens and Gungorb; Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2018; Osawa & Jiménez Reference Osawa and Jiménez2018; Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2019). By using this method (Moisy & Jiménez Reference Moisy and Jiménez2004), we can obtain the spatial information for individual

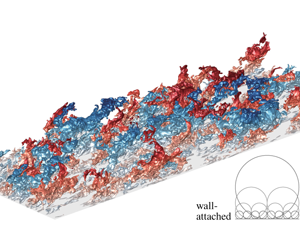

$u$ cluster, we use the connectivity of neighbouring six-orthogonal grids at a given node in Cartesian coordinates (Moisy & Jiménez Reference Moisy and Jiménez2004; Del Álamo et al. Reference Del Álamo, Jiménez, Zandonade and Moser2006; Lozano-Durán et al. Reference Lozano-Durán, Flores and Jiménez2012; Lozano-Durán & Jiménez Reference Lozano-Durán and Jiménez2014; Sillero Reference Sillero2014; Dong et al. Reference Dong, Lozano-Durán, Sekimoto and Jiménez2017; Maciel et al. Reference Maciel, Gungor and Simens2017a,Reference Maciel, Simens and Gungorb; Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2018; Osawa & Jiménez Reference Osawa and Jiménez2018; Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2019). By using this method (Moisy & Jiménez Reference Moisy and Jiménez2004), we can obtain the spatial information for individual ![]() $u$ clusters. Figure 4 shows iso-surfaces of

$u$ clusters. Figure 4 shows iso-surfaces of ![]() $u$ in an instantaneous flow field of the APG TBL. Positive-

$u$ in an instantaneous flow field of the APG TBL. Positive-![]() $u$ (high speed;

$u$ (high speed; ![]() $u>\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}u_{rms}$) and negative-

$u>\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}u_{rms}$) and negative-![]() $u$ (low speed;

$u$ (low speed; ![]() $u<-\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}u_{rms}$) clusters are represented by red and blue, respectively, and wall-normal locations are illustrated by colour depths. The two insets show samples of the attached and detached

$u<-\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}u_{rms}$) clusters are represented by red and blue, respectively, and wall-normal locations are illustrated by colour depths. The two insets show samples of the attached and detached ![]() $u$ structures. The length scales of an individual cluster are defined as the dimensions of the box circumscribing the object, i.e.

$u$ structures. The length scales of an individual cluster are defined as the dimensions of the box circumscribing the object, i.e. ![]() $l_{x}$,

$l_{x}$, ![]() $l_{y}$ and

$l_{y}$ and ![]() $l_{z}$ are its streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise lengths, respectively. The wall-normal height (

$l_{z}$ are its streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise lengths, respectively. The wall-normal height (![]() $l_{y}$) of clusters is defined as

$l_{y}$) of clusters is defined as ![]() $l_{y}=y_{max}-y_{min}$, which are the maximum and minimum distances from the wall.

$l_{y}=y_{max}-y_{min}$, which are the maximum and minimum distances from the wall.

Figure 4. The 3-D iso-surfaces of ![]() $u$ in the APG TBL. The left- and right-hand insets show samples of the attached and detached

$u$ in the APG TBL. The left- and right-hand insets show samples of the attached and detached ![]() $u$ structures, respectively.

$u$ structures, respectively.

Figure 5. (a) Percolation diagram for the detected ![]() $u$ clusters. The variations with

$u$ clusters. The variations with ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$ in the total volume (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$ in the total volume (![]() $V$) and the total number (

$V$) and the total number (![]() $N$) of clusters. (b) The number of

$N$) of clusters. (b) The number of ![]() $u$ clusters per unit wall-parallel area (

$u$ clusters per unit wall-parallel area (![]() $n^{\ast }$) with respect to

$n^{\ast }$) with respect to ![]() $y_{min}$ and

$y_{min}$ and ![]() $y_{max}$.

$y_{max}$.

The percolation diagram for the identified ![]() $u$ clusters in figure 5(a) enables the choice of

$u$ clusters in figure 5(a) enables the choice of ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$. The percolation theory describes the statistics of the contiguous nodes in a randomly distributed system. The total number (N) and total volume (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$. The percolation theory describes the statistics of the contiguous nodes in a randomly distributed system. The total number (N) and total volume (![]() $V$) at a particular

$V$) at a particular ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$ are normalized by the maximum

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$ are normalized by the maximum ![]() $N$ (

$N$ (![]() $N_{max}$) and

$N_{max}$) and ![]() $V$ (

$V$ (![]() $V_{max}$) over

$V_{max}$) over ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$, respectively, which are the sum of the corresponding clusters for negative and positive fluctuations. The normalized volume (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$, respectively, which are the sum of the corresponding clusters for negative and positive fluctuations. The normalized volume (![]() $V/V_{max}$) increases with decreases in

$V/V_{max}$) increases with decreases in ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$, and in particular it significantly changes in the range

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$, and in particular it significantly changes in the range ![]() $1.2<\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}<1.7$, which indicates the occurrence of the percolation crisis. Within this region, the number ratio (

$1.2<\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}<1.7$, which indicates the occurrence of the percolation crisis. Within this region, the number ratio (![]() $N/N_{max}$) shows a peak at

$N/N_{max}$) shows a peak at ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}=1.5$. As

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}=1.5$. As ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$ decreases, new clusters arise or some of the previously identified clusters become connected. The trade-off between the two effects leads to the presence of a peak in the variation in

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$ decreases, new clusters arise or some of the previously identified clusters become connected. The trade-off between the two effects leads to the presence of a peak in the variation in ![]() $N/N_{max}$; the former behaviour is dominant for

$N/N_{max}$; the former behaviour is dominant for ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}>1.5$ and vice versa. In addition, the variations in

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}>1.5$ and vice versa. In addition, the variations in ![]() $V/V_{max}$ and

$V/V_{max}$ and ![]() $N/N_{max}$ in the APG and ZPG TBLs coincide, indicating that the percolation behaviour of the

$N/N_{max}$ in the APG and ZPG TBLs coincide, indicating that the percolation behaviour of the ![]() $u$ clusters is independent of the pressure gradient. In the present study, we select

$u$ clusters is independent of the pressure gradient. In the present study, we select ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}=1.5$ based on the percolation transition.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}=1.5$ based on the percolation transition.

Figure 5(b) shows the number of ![]() $u$ clusters per unit wall-parallel area (

$u$ clusters per unit wall-parallel area (![]() $A_{xz}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{x}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{z}$) as a function of

$A_{xz}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{x}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{z}$) as a function of ![]() $y_{min}$ and

$y_{min}$ and ![]() $y_{max}$, which are the minimum and maximum distances from the wall:

$y_{max}$, which are the minimum and maximum distances from the wall:

where ![]() $n$ is the number of identified

$n$ is the number of identified ![]() $u$ clusters and

$u$ clusters and ![]() $m$ is the number of instantaneous flow fields used to detect

$m$ is the number of instantaneous flow fields used to detect ![]() $u$ clusters (

$u$ clusters (![]() $m=2758$ for the APG TBL and 2100 for the ZPG TBL). Here, the colour and line contours of

$m=2758$ for the APG TBL and 2100 for the ZPG TBL). Here, the colour and line contours of ![]() $n^{\ast }$ are for the APG and ZPG TBLs, respectively. Only the

$n^{\ast }$ are for the APG and ZPG TBLs, respectively. Only the ![]() $u$ clusters with volumes larger than

$u$ clusters with volumes larger than ![]() $30^{3}$ wall units are analysed (Del Álamo et al. Reference Del Álamo, Jiménez, Zandonade and Moser2006). The

$30^{3}$ wall units are analysed (Del Álamo et al. Reference Del Álamo, Jiménez, Zandonade and Moser2006). The ![]() $u$ structures are divided into two groups: those are observed at

$u$ structures are divided into two groups: those are observed at ![]() $y_{min}^{+}\approx 0$ and

$y_{min}^{+}\approx 0$ and ![]() $y_{min}^{+}>0$, i.e. the wall-attached and wall-detached structures, respectively. Following the research of Hwang & Sung (Reference Hwang and Sung2018) and Hwang & Sung (Reference Hwang and Sung2019), we defined the wall-attached objects as those with

$y_{min}^{+}>0$, i.e. the wall-attached and wall-detached structures, respectively. Following the research of Hwang & Sung (Reference Hwang and Sung2018) and Hwang & Sung (Reference Hwang and Sung2019), we defined the wall-attached objects as those with ![]() $y_{min}^{+}\approx 0$; i.e. those structures that are physically attached to the wall. Note that Townsend’s attached-eddy hypothesis does not suppose that attached eddies are physically anchored to the wall because attached eddies are assumed to be inviscid. Of course, the present study could define the attached structures as those structures with

$y_{min}^{+}\approx 0$; i.e. those structures that are physically attached to the wall. Note that Townsend’s attached-eddy hypothesis does not suppose that attached eddies are physically anchored to the wall because attached eddies are assumed to be inviscid. Of course, the present study could define the attached structures as those structures with ![]() $y_{min}$ below the viscous sublayer (

$y_{min}$ below the viscous sublayer (![]() $y^{+}=5$) but for 80 % of such structures

$y^{+}=5$) but for 80 % of such structures ![]() $y_{min}^{+}\approx 0$. In addition, 94 % of the tall structures (

$y_{min}^{+}\approx 0$. In addition, 94 % of the tall structures (![]() $l_{y}^{+}=y_{max}^{+}-y_{min}^{+}>100$ and

$l_{y}^{+}=y_{max}^{+}-y_{min}^{+}>100$ and ![]() $y_{min}^{+}<5$) examined in the present work are based on

$y_{min}^{+}<5$) examined in the present work are based on ![]() $y_{min}^{+}\approx 0$, which indicates that the results of the present study are not affected by the use of this criterion.

$y_{min}^{+}\approx 0$, which indicates that the results of the present study are not affected by the use of this criterion.

With the present criterion (i.e. ![]() $y_{min}^{+}\approx 0$), we can analyse the wall-normal variations of the turbulence statistics carried by these structures according to their height (

$y_{min}^{+}\approx 0$), we can analyse the wall-normal variations of the turbulence statistics carried by these structures according to their height (![]() $l_{y}$) without any interpolation since

$l_{y}$) without any interpolation since ![]() $l_{y}=y_{max}$. Moreover, we distinguish between the words ‘attached’ and ‘self-similar’ in contrast to several previous studies discussing the attached-eddy hypothesis because the clusters of

$l_{y}=y_{max}$. Moreover, we distinguish between the words ‘attached’ and ‘self-similar’ in contrast to several previous studies discussing the attached-eddy hypothesis because the clusters of ![]() $u$ can be decomposed into attached self-similar, attached non-self-similar, detached self-similar and detached non-self-similar motions. Here, ‘self-similar motions’ are defined as the clusters whose characteristic length scales are proportional to their height.

$u$ can be decomposed into attached self-similar, attached non-self-similar, detached self-similar and detached non-self-similar motions. Here, ‘self-similar motions’ are defined as the clusters whose characteristic length scales are proportional to their height.

For the attached structures ![]() $(y_{min}^{+}\approx 0)$,

$(y_{min}^{+}\approx 0)$, ![]() $y_{max}$ varies from the near-wall region to the outer region and in particular an outer peak emerges near

$y_{max}$ varies from the near-wall region to the outer region and in particular an outer peak emerges near ![]() $y_{max}^{+}=700$, which implies the dominance of very tall attached structures in the vicinity of the boundary edge. On the other hand, the detached

$y_{max}^{+}=700$, which implies the dominance of very tall attached structures in the vicinity of the boundary edge. On the other hand, the detached ![]() $u$ structures are distributed in a narrow band and are densely populated in the outer region (see § 4). A weak peak appears at

$u$ structures are distributed in a narrow band and are densely populated in the outer region (see § 4). A weak peak appears at ![]() $y_{min}^{+}\approx 7$ and

$y_{min}^{+}\approx 7$ and ![]() $y_{max}^{+}\approx 50$, but its strength is at least two orders of magnitude lower than that in the outer region. The structures in this region may be associated with debris from attached structures or objects that are evolving towards attached ones (Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2018). A further exploration of their temporal evolution is necessary, although beyond the scope of the present work.

$y_{max}^{+}\approx 50$, but its strength is at least two orders of magnitude lower than that in the outer region. The structures in this region may be associated with debris from attached structures or objects that are evolving towards attached ones (Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2018). A further exploration of their temporal evolution is necessary, although beyond the scope of the present work.

Figure 6 shows the 3-D iso-surfaces of the intense ![]() $u$ (

$u$ (![]() $|u|>1.5u_{rms}$) in the APG TBL. Through the identification of individual clusters, we can decompose

$|u|>1.5u_{rms}$) in the APG TBL. Through the identification of individual clusters, we can decompose ![]() $u$ fields into

$u$ fields into ![]() $u_{attached}$,

$u_{attached}$, ![]() $u_{detached}$ and

$u_{detached}$ and ![]() $u_{weak}$ (

$u_{weak}$ (![]() $|u|<1.5u_{rms}$). The blue and red contours indicate negative

$|u|<1.5u_{rms}$). The blue and red contours indicate negative ![]() $u$ and positive

$u$ and positive ![]() $u$, respectively. The intensity of the colour represents the wall-normal distance. As can be seen in this figure, the iso-surfaces of

$u$, respectively. The intensity of the colour represents the wall-normal distance. As can be seen in this figure, the iso-surfaces of ![]() $u_{attached}$ are significantly extended in the streamwise direction, and the negative and positive

$u_{attached}$ are significantly extended in the streamwise direction, and the negative and positive ![]() $u_{attached}$ are aligned side by side along the spanwise direction. On the other hand,

$u_{attached}$ are aligned side by side along the spanwise direction. On the other hand, ![]() $u_{detached}$ is much smaller than the large

$u_{detached}$ is much smaller than the large ![]() $u_{attached}$.

$u_{attached}$.

Figure 6. The 3-D iso-surfaces of ![]() $u$ (

$u$ (![]() $=u_{attached}+u_{detached}+u_{weak}$) in the APG TBL. Red and blue represent intense positive and negative

$=u_{attached}+u_{detached}+u_{weak}$) in the APG TBL. Red and blue represent intense positive and negative ![]() $u$, respectively.

$u$, respectively.

Figure 7. Profiles of (a) ![]() $\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$ and (b)

$\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$ and (b) ![]() $\langle uu\rangle _{attached}^{+}$ and

$\langle uu\rangle _{attached}^{+}$ and ![]() $\langle uu\rangle _{detached}^{+}$. Profiles of (c)

$\langle uu\rangle _{detached}^{+}$. Profiles of (c) ![]() $\langle -uv\rangle ^{+}$ and (d)

$\langle -uv\rangle ^{+}$ and (d) ![]() $\langle -uv\rangle _{attached}^{+}$ and

$\langle -uv\rangle _{attached}^{+}$ and ![]() $\langle -uv\rangle _{detached}^{+}$.

$\langle -uv\rangle _{detached}^{+}$.

Next, we examine the contributions of the attached and detached ![]() $u$ structures to

$u$ structures to ![]() $\langle uu\rangle$. Figure 7(a) shows the profiles of

$\langle uu\rangle$. Figure 7(a) shows the profiles of ![]() $\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$, where the magnitude of

$\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$, where the magnitude of ![]() $\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$ in the outer region is enhanced by the presence of a secondary peak near

$\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$ in the outer region is enhanced by the presence of a secondary peak near ![]() $y^{+}=240$ in the APG TBL (red line). The streamwise Reynolds stresses carried by the attached and detached

$y^{+}=240$ in the APG TBL (red line). The streamwise Reynolds stresses carried by the attached and detached ![]() $u$ structures are presented in figure 7(b) and are defined as

$u$ structures are presented in figure 7(b) and are defined as

where ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{attached}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{attached}$ and ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{detached}$ are the domains of all constituent points of attached and detached structures, respectively, and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}_{detached}$ are the domains of all constituent points of attached and detached structures, respectively, and ![]() $V_{DoI}$ (

$V_{DoI}$ (![]() $=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{x}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{y}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{z}$) is the volume of the DoI. The attached

$=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{x}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{y}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{z}$) is the volume of the DoI. The attached ![]() $u$ structures account for over half of

$u$ structures account for over half of ![]() $\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$, whereas the detached

$\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$, whereas the detached ![]() $u$ structures contribute to less than 13 % of

$u$ structures contribute to less than 13 % of ![]() $\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$. The remainder is responsible for weak turbulence. In addition, the shape of

$\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$. The remainder is responsible for weak turbulence. In addition, the shape of ![]() $\langle uu\rangle _{attached}^{+}$ is similar to that of

$\langle uu\rangle _{attached}^{+}$ is similar to that of ![]() $\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$. The wall-normal location of the inner peak of

$\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$. The wall-normal location of the inner peak of ![]() $\langle uu\rangle _{attached}^{+}$ is at

$\langle uu\rangle _{attached}^{+}$ is at ![]() $y^{+}$

$y^{+}$![]() ${\approx}$ 15, and the outer peak of

${\approx}$ 15, and the outer peak of ![]() $\langle uu\rangle _{attached}^{+}$ arises at

$\langle uu\rangle _{attached}^{+}$ arises at ![]() $y^{+}=210$. In contrast to

$y^{+}=210$. In contrast to ![]() $\langle uu\rangle _{attached}^{+}$, the profiles of

$\langle uu\rangle _{attached}^{+}$, the profiles of ![]() $\langle uu\rangle _{detached}^{+}$ in the APG and ZPG TBLs follow each other closely up to

$\langle uu\rangle _{detached}^{+}$ in the APG and ZPG TBLs follow each other closely up to ![]() $y^{+}=100$. At

$y^{+}=100$. At ![]() $y^{+}>100$, the magnitude of

$y^{+}>100$, the magnitude of ![]() $\langle uu\rangle _{detached}^{+}$ in the APG TBL is larger than that in the ZPG TBL, and there is an outer peak at

$\langle uu\rangle _{detached}^{+}$ in the APG TBL is larger than that in the ZPG TBL, and there is an outer peak at ![]() $y/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$ = 0.5. This result indicates that the detached structures within

$y/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$ = 0.5. This result indicates that the detached structures within ![]() $y^{+}<100$ are defect by the pressure gradient. Note that the present Reynolds number (

$y^{+}<100$ are defect by the pressure gradient. Note that the present Reynolds number (![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}\approx 800$) is low. As the Reynolds number increases further, it is expected that the contribution of the attached structures will increase, and thus the similarity of the structures will be maintained in a manner analogous to that observed in turbulent pipe flows with

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}\approx 800$) is low. As the Reynolds number increases further, it is expected that the contribution of the attached structures will increase, and thus the similarity of the structures will be maintained in a manner analogous to that observed in turbulent pipe flows with ![]() $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=930$ and 3008 (Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2019).

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}}=930$ and 3008 (Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2019).

Figure 7(c) shows the profiles of ![]() $\langle -uv\rangle ^{+}$; a peak is located at

$\langle -uv\rangle ^{+}$; a peak is located at ![]() $y^{+}=280$ in the results for the APG TBL. We compute

$y^{+}=280$ in the results for the APG TBL. We compute ![]() $\langle -uv\rangle$ from the results for the attached

$\langle -uv\rangle$ from the results for the attached ![]() $(\langle -uv\rangle _{attached})$ and detached

$(\langle -uv\rangle _{attached})$ and detached ![]() $(\langle -uv\rangle _{detached})$ structures obtained from (2.2) and (2.3). The attached structures contribute over 40 % of

$(\langle -uv\rangle _{detached})$ structures obtained from (2.2) and (2.3). The attached structures contribute over 40 % of ![]() $\langle -uv\rangle ^{+}$, which is similar to a previous result for the wall-attached ejections and sweeps of APG TBLs (Maciel et al. Reference Maciel, Gungor and Simens2017a). In the present study, the identified wall-attached structures carry approximately half of

$\langle -uv\rangle ^{+}$, which is similar to a previous result for the wall-attached ejections and sweeps of APG TBLs (Maciel et al. Reference Maciel, Gungor and Simens2017a). In the present study, the identified wall-attached structures carry approximately half of ![]() $\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$ and

$\langle uu\rangle ^{+}$ and ![]() $\langle -uv\rangle ^{+}$, which indicates that they are the main energy-containing motions.

$\langle -uv\rangle ^{+}$, which indicates that they are the main energy-containing motions.

3 Wall-attached structures

In this section, we examine the identified attached structures by focusing on the eddy models proposed by Perry & Marusic (Reference Perry and Marusic1995), which distinguish three types of eddies. First, type A eddies are self-similar and the main energy-containing motions in the logarithmic region. In this sense, such eddies are universal structures in wall turbulence. Type B eddies are characterized by the boundary layer thickness and are responsible for the turbulence statistics in the outer region and at low-wavenumber energies. Perry & Marusic (Reference Perry and Marusic1995) employed the type B eddies to model the outer peak of the streamwise Reynolds stress in APG TBLs because the intensity predicted by only considering type A eddies does not agree with experimental results for the outer region. Type C eddies are associated with small-scale motions. Although Perry & Marusic (Reference Perry and Marusic1995) concluded that type B eddies are physically detached from the wall, recent studies have shown that very-large-scale motions (VLSMs) or superstructures (![]() ${>}O(3\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF})$) are related to type B eddies because these large-scale structures are characterized by the outer length scale (Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007b; Marusic & Monty Reference Marusic and Monty2019). However, the LSMs and VLSMs penetrate into the near-wall region and impose their footprints (Abe, Kawamura & Choi Reference Abe, Kawamura and Choi2004; Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007a; Hwang Reference Hwang2016; Hwang, Lee & Sung Reference Hwang, Lee and Sung2016a; Hwang et al. Reference Hwang, Lee, Sung and Zaki2016b; Yoon et al. Reference Yoon, Hwang, Lee, Sung and Kim2016; Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2017), which indicates that they can physically adhere to the wall. In spectral space, the energies carried by structures of types A, B and C are overlaid, and thus it is challenging to extract typical motion types from the energy spectrum (Marusic & Monty Reference Marusic and Monty2019). Very recently, Baars & Marusic (Reference Baars and Marusic2020a,Reference Baars and Marusicb) successfully decomposed several types of motions in wavenumber space using spectral coherence analysis. In the present study, we simply decomposed the identified turbulence motions according to their height and now present the statistical properties of each structure, which are superimposed on those of types A, B and C motions described by Perry and co-workers.

${>}O(3\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF})$) are related to type B eddies because these large-scale structures are characterized by the outer length scale (Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007b; Marusic & Monty Reference Marusic and Monty2019). However, the LSMs and VLSMs penetrate into the near-wall region and impose their footprints (Abe, Kawamura & Choi Reference Abe, Kawamura and Choi2004; Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007a; Hwang Reference Hwang2016; Hwang, Lee & Sung Reference Hwang, Lee and Sung2016a; Hwang et al. Reference Hwang, Lee, Sung and Zaki2016b; Yoon et al. Reference Yoon, Hwang, Lee, Sung and Kim2016; Hwang & Sung Reference Hwang and Sung2017), which indicates that they can physically adhere to the wall. In spectral space, the energies carried by structures of types A, B and C are overlaid, and thus it is challenging to extract typical motion types from the energy spectrum (Marusic & Monty Reference Marusic and Monty2019). Very recently, Baars & Marusic (Reference Baars and Marusic2020a,Reference Baars and Marusicb) successfully decomposed several types of motions in wavenumber space using spectral coherence analysis. In the present study, we simply decomposed the identified turbulence motions according to their height and now present the statistical properties of each structure, which are superimposed on those of types A, B and C motions described by Perry and co-workers.

Figure 8. (a) The variation in ![]() $n_{attached}^{\ast }$ with

$n_{attached}^{\ast }$ with ![]() $l_{y}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$. The inset shows an enlarged view of the region

$l_{y}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}$. The inset shows an enlarged view of the region ![]() $l_{y}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}=0.32{-}0.72$. (b) Pre-multiplied population density of wall-attached structures,

$l_{y}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}=0.32{-}0.72$. (b) Pre-multiplied population density of wall-attached structures, ![]() $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6EF}=(l_{y}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF})n_{attached}^{\ast }$.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6EF}=(l_{y}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF})n_{attached}^{\ast }$.

We examine the population density ![]() $(n_{attached}^{\ast })$ of attached

$(n_{attached}^{\ast })$ of attached ![]() $u$ structures with respect to

$u$ structures with respect to ![]() $l_{y}$. Here,

$l_{y}$. Here, ![]() $n_{attached}^{\ast }$ is defined as the number of attached

$n_{attached}^{\ast }$ is defined as the number of attached ![]() $u$ structures (

$u$ structures (![]() $n_{attached}$) per unit wall-parallel area with respect to

$n_{attached}$) per unit wall-parallel area with respect to ![]() $l_{y}$:

$l_{y}$:

where ![]() $n_{attached}$ is a function of

$n_{attached}$ is a function of ![]() $l_{y}$,

$l_{y}$, ![]() $m$ is the number of snapshots and

$m$ is the number of snapshots and ![]() $A_{xz}$ is the wall-parallel area of the DoI. For attached structures,

$A_{xz}$ is the wall-parallel area of the DoI. For attached structures, ![]() $l_{y}$ (

$l_{y}$ (![]() $=y_{max}$) scales with the distance from the wall due to

$=y_{max}$) scales with the distance from the wall due to ![]() $y_{min}\approx 0$ (figure 5b). Hwang & Sung (Reference Hwang and Sung2018) showed that the population density of attached

$y_{min}\approx 0$ (figure 5b). Hwang & Sung (Reference Hwang and Sung2018) showed that the population density of attached ![]() $u$ structures (

$u$ structures (![]() $0.3<l_{y}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}<0.6$) in a ZPG TBL is inversely proportional to

$0.3<l_{y}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}<0.6$) in a ZPG TBL is inversely proportional to ![]() $l_{y}$, reminiscent of the hierarchical length-scale distribution of attached eddies (Perry & Chong Reference Perry and Chong1982). Perry & Chong (Reference Perry and Chong1982) assumed that each hierarchy is geometrically similar and that all length scales double from one hierarchy to the next, leading to the inverse power-law distribution in PDFs. In addition, Hwang & Sung (Reference Hwang and Sung2018) observed a peak near the boundary layer edge (i.e. a relatively high occurrence of tall structures), which is consistent with the modification in the PDF of attached eddies proposed by Perry et al. (Reference Perry, Henbest and Chong1986). Figure 8(a) shows the distributions of

$l_{y}$, reminiscent of the hierarchical length-scale distribution of attached eddies (Perry & Chong Reference Perry and Chong1982). Perry & Chong (Reference Perry and Chong1982) assumed that each hierarchy is geometrically similar and that all length scales double from one hierarchy to the next, leading to the inverse power-law distribution in PDFs. In addition, Hwang & Sung (Reference Hwang and Sung2018) observed a peak near the boundary layer edge (i.e. a relatively high occurrence of tall structures), which is consistent with the modification in the PDF of attached eddies proposed by Perry et al. (Reference Perry, Henbest and Chong1986). Figure 8(a) shows the distributions of ![]() $n_{attached}^{\ast }$. For the APG TBL (red), there is a region for which

$n_{attached}^{\ast }$. For the APG TBL (red), there is a region for which ![]() $n_{attached}^{\ast }$ is inversely proportional to