1. Introduction

Since friction drag in a turbulent flow is dominant in many industrial applications (Gad-el-Hak Reference Gad-el-Hak1994), turbulent friction drag reduction is of great importance for energy saving. To establish flow control methods for turbulent friction drag reduction in many practical situations, it is crucial to perform high-fidelity numerical simulations of controlled turbulent flows at reasonably high Reynolds numbers and find a scaling law applicable at practically high Reynolds numbers.

Flow control methods are classified into two categories: passive and active control methods. Although passive control methods, e.g. the use of riblets (Walsh Reference Walsh1983) and polymer additives (White & Mungal Reference White and Mungal2008) and bubble injection (Murai Reference Murai2014), have the advantage that their practical implementation is relatively easier, it is not always easy to put them into practice owing to the additional maintenance cost. On the other hand, although active control methods have the disadvantage that their implementation is more difficult owing to the requirement of a continuous energy input from an external system, their larger drag reduction effects encourage us to further investigate active control methods. In particular, predetermined control methods have a higher potential for drag reduction and the advantage of their easier implementation than feedback control methods, which have been widely investigated in terms of various approaches (Choi, Moin & Kim Reference Choi, Moin and Kim1994; Lee, Kim & Choi Reference Lee, Kim and Choi1998; Iwamoto, Suzuki & Kasagi Reference Iwamoto, Suzuki and Kasagi2002; Kim Reference Kim2003; Kim & Bewley Reference Kim and Bewley2007; Kasagi, Suzuki & Fukagata Reference Kasagi, Suzuki and Fukagata2009; Nakashima, Fukagata & Luhar Reference Nakashima, Fukagata and Luhar2017; Kawagoe et al. Reference Kawagoe, Nakashima, Luhar and Fukagata2019). Therefore, we can highly expect the practical use of predetermined control methods.

Among various predetermined control methods (e.g. Ricco, Skote & Leschziner Reference Ricco, Skote and Leschziner2021; Fukagata, Iwamoto & Hasegawa Reference Fukagata, Iwamoto and Hasegawa2024), streamwise travelling wave-like wall deformation is considered one of the most attractive control methods. Unlike streamwise travelling waves generated by blowing/suction (Min et al. Reference Min, Kang, Speyer and Kim2006; Lee, Min & Kim Reference Lee, Min and Kim2008; Lieu, Moarref & Jovanović Reference Lieu, Moarref and Jovanović2010; Moarref & Jovanović Reference Moarref and Jovanović2010; Mamori, Iwamoto & Murata Reference Mamori, Iwamoto and Murata2014; Koganezawa et al. Reference Koganezawa, Mitsuishi, Shimura, Iwamoto, Mamori and Murata2019; Ogino et al. Reference Ogino, Mamori, Fukushima, Fukudome and Yamamoto2019; Mamori et al. Reference Mamori, Fukudome, Ogino, Fukushima and Yamamoto2021), its implementation in industrial applications is expected to be relatively easier, as demonstrated by the experiment conducted by Suzuki et al. (Reference Suzuki, Shimura, Mitsuishi, Iwamoto and Murata2019), who used a rubber sheet driven by a single piezoelectric actuator. Nakanishi, Mamori & Fukagata (Reference Nakanishi, Mamori and Fukagata2012) investigated the control effect of a streamwise travelling wave generated by wall deformation in a low-Reynolds-number turbulent channel flow by direct numerical simulation (DNS). They achieved the relaminarization of the turbulent flow at a constant flow rate and bulk Reynolds number ![]() $Re_b = 5600$, which corresponds to friction Reynolds number

$Re_b = 5600$, which corresponds to friction Reynolds number ![]() $Re_\tau \simeq 180$ in an uncontrolled flow. Nabae, Kawai & Fukagata (Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020) revisited the same problem under a constant-pressure-gradient (CPG) condition at three different friction Reynolds numbers. Very recently, Albers, Shao & Schröder (Reference Albers, Shao and Schröder2024) have achieved a drag reduction of more than

$Re_\tau \simeq 180$ in an uncontrolled flow. Nabae, Kawai & Fukagata (Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020) revisited the same problem under a constant-pressure-gradient (CPG) condition at three different friction Reynolds numbers. Very recently, Albers, Shao & Schröder (Reference Albers, Shao and Schröder2024) have achieved a drag reduction of more than ![]() $50\,\%$ in a spatially developing compressible turbulent boundary layer flow using streamwise travelling wave-like wall deformation.

$50\,\%$ in a spatially developing compressible turbulent boundary layer flow using streamwise travelling wave-like wall deformation.

As a different control technique, a streamwise travelling wave of spanwise wall oscillation has been widely investigated (Ricco et al. Reference Ricco, Skote and Leschziner2021). Gatti & Quadrio (Reference Gatti and Quadrio2016) proposed a model for predicting the drag reduction rate at significantly high Reynolds numbers based on DNS results at low Reynolds numbers. Subsequently, for some specific parameter sets, the usefulness of this prediction model has been shown in recent studies (Marusic et al. Reference Marusic, Chandran, Rouhi, Fu, Wine, Holloway, Chung and Smits2021; Rouhi et al. Reference Rouhi, Fu, Chandran, Zampiron, Smits and Marusic2023) by conducting experiments up to ![]() $Re_\tau = 12\,800$ and large-eddy simulation (LES) up to

$Re_\tau = 12\,800$ and large-eddy simulation (LES) up to ![]() $Re_\tau = 4000$. In addition, Marusic et al. (Reference Marusic, Chandran, Rouhi, Fu, Wine, Holloway, Chung and Smits2021) proposed a new control strategy for drag reduction in a high-Reynolds-number turbulent flow. According to Marusic et al. (Reference Marusic, Chandran, Rouhi, Fu, Wine, Holloway, Chung and Smits2021), the contribution to the total wall shear stress from the large-eddy component increases as the Reynolds number increases: for example, the ratios of the large-eddy component to the total shear stress at

$Re_\tau = 4000$. In addition, Marusic et al. (Reference Marusic, Chandran, Rouhi, Fu, Wine, Holloway, Chung and Smits2021) proposed a new control strategy for drag reduction in a high-Reynolds-number turbulent flow. According to Marusic et al. (Reference Marusic, Chandran, Rouhi, Fu, Wine, Holloway, Chung and Smits2021), the contribution to the total wall shear stress from the large-eddy component increases as the Reynolds number increases: for example, the ratios of the large-eddy component to the total shear stress at ![]() $Re_\tau = 10^3$ and

$Re_\tau = 10^3$ and ![]() $10^5$ are about

$10^5$ are about ![]() $8\,\%$ and

$8\,\%$ and ![]() $30\,\%$, respectively. By targeting this large-eddy component, they achieved substantial drag reduction at

$30\,\%$, respectively. By targeting this large-eddy component, they achieved substantial drag reduction at ![]() $Re_\tau = 12\,800$ by using a streamwise travelling wave with an oscillation period of more than

$Re_\tau = 12\,800$ by using a streamwise travelling wave with an oscillation period of more than ![]() $350$ in wall-unit time, which corresponds to ‘large-eddy actuation’ defined in their paper.

$350$ in wall-unit time, which corresponds to ‘large-eddy actuation’ defined in their paper.

Unlike a travelling wave of spanwise wall oscillation, the drag reduction effect of a travelling wave generated by wall deformation has not been investigated even at moderately high Reynolds numbers ![]() $Re_\tau \geqslant 10^3$ by either experiments or high-fidelity numerical simulations. To predict the drag reduction rate by streamwise travelling wave-like wall deformation over a wide range of friction Reynolds numbers, Nabae et al. (Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020) proposed a semi-empirical formula for the mean velocity profile based on the scaling obtained by their DNS results. Their prediction implies that drag reduction rate of about 20 %–25 % was obtained even at practically high Reynolds numbers,

$Re_\tau \geqslant 10^3$ by either experiments or high-fidelity numerical simulations. To predict the drag reduction rate by streamwise travelling wave-like wall deformation over a wide range of friction Reynolds numbers, Nabae et al. (Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020) proposed a semi-empirical formula for the mean velocity profile based on the scaling obtained by their DNS results. Their prediction implies that drag reduction rate of about 20 %–25 % was obtained even at practically high Reynolds numbers, ![]() $Re_\tau \sim 10^5\unicode{x2013}10^6$. In this semi-empirical formula, the Kármán constant was assumed to be unchanged by the control: similar to the prediction model proposed by Gatti & Quadrio (Reference Gatti and Quadrio2016), only a vertical shift of the mean velocity profile in the logarithmic region was considered. Note that Gatti & Quadrio (Reference Gatti and Quadrio2016) considered control using a streamwise travelling wave of spanwise wall oscillation. One cannot directly compare the drag reduction effect in the case of wall deformation with that in the case of wall oscillation because the pressure drag as well as the friction drag should be considered in the case of wall deformation. Therefore, to validate the semi-empirical formula proposed by Nabae et al. (Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020) for practical large-scale turbulent flows, we should investigate the drag reduction effect in a high-Reynolds-number range where the logarithmic region in the mean velocity profile is clearly observed. According to a very classical estimation by Pope (Reference Pope2000), the logarithmic region is defined as

$Re_\tau \sim 10^5\unicode{x2013}10^6$. In this semi-empirical formula, the Kármán constant was assumed to be unchanged by the control: similar to the prediction model proposed by Gatti & Quadrio (Reference Gatti and Quadrio2016), only a vertical shift of the mean velocity profile in the logarithmic region was considered. Note that Gatti & Quadrio (Reference Gatti and Quadrio2016) considered control using a streamwise travelling wave of spanwise wall oscillation. One cannot directly compare the drag reduction effect in the case of wall deformation with that in the case of wall oscillation because the pressure drag as well as the friction drag should be considered in the case of wall deformation. Therefore, to validate the semi-empirical formula proposed by Nabae et al. (Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020) for practical large-scale turbulent flows, we should investigate the drag reduction effect in a high-Reynolds-number range where the logarithmic region in the mean velocity profile is clearly observed. According to a very classical estimation by Pope (Reference Pope2000), the logarithmic region is defined as ![]() $y^+ > 30$ and

$y^+ > 30$ and ![]() $y/\delta < 0.3$, where

$y/\delta < 0.3$, where ![]() $y$ is the distance from the wall and

$y$ is the distance from the wall and ![]() $\delta$ is the channel half-width. Therefore,

$\delta$ is the channel half-width. Therefore, ![]() $Re_\tau > 10^3$ is required to obtain the logarithmic region of one decade.

$Re_\tau > 10^3$ is required to obtain the logarithmic region of one decade.

As a useful high-fidelity numerical simulation technique, LES has been extensively utilized for the investigation of a turbulent flow at high Reynolds numbers. Since the pioneering study by Smagorinsky (Reference Smagorinsky1963), various subgrid-scale (SGS) models for LES have been proposed thus far (Meneveau & Katz Reference Meneveau and Katz2000; Moser, Haering & Yalla Reference Moser, Haering and Yalla2021). The Smagorinsky model (Smagorinsky Reference Smagorinsky1963) and wall-adapting local eddy-viscosity (WALE) model (Nicoud & Ducros Reference Nicoud and Ducros1999) are relatively simple eddy-viscosity models; thus, their implementation is easy and the required CPU time is small. However, the model constants used to determine model parameters, e.g. the Smagorinsky constant ![]() $C_s$ (described in § 2), depend on flow fields: for example,

$C_s$ (described in § 2), depend on flow fields: for example, ![]() $C_s = 0.2$ for homogeneous turbulence and

$C_s = 0.2$ for homogeneous turbulence and ![]() $C_s = 0.1$ for turbulent channel flows. To solve this problem, the dynamic Smagorinsky model (DSM) (Germano et al. Reference Germano, Piomelli, Moin and Cabot1991; Lilly Reference Lilly1992) has been proposed. In the DSM, we can dynamically determine model parameters without any empirical model constants. However, the local determination of model parameters produces positive and negative model parameters, leading to numerical instabilities due to the negative viscosity. To remove the negative viscosity, the calculation of parameters in the DSM requires the averaging procedure in homogeneous directions of turbulent flows. Although this averaging procedure leads to numerical stability, more CPU time is required. In addition, under complex boundary conditions due to the flow control, e.g. wall deformation, the averaging procedure in the homogeneous directions is not reasonable. The validation of SGS models has been examined mainly in terms of uncontrolled canonical flows such as channel and boundary-layer flows. Although there are some LES studies on controlled flows (e.g. Chang, Collis & Ramakrishnan Reference Chang, Collis and Ramakrishnan2002), a detailed assessment of SGS models for controlled flows has not yet been realized.

$C_s = 0.1$ for turbulent channel flows. To solve this problem, the dynamic Smagorinsky model (DSM) (Germano et al. Reference Germano, Piomelli, Moin and Cabot1991; Lilly Reference Lilly1992) has been proposed. In the DSM, we can dynamically determine model parameters without any empirical model constants. However, the local determination of model parameters produces positive and negative model parameters, leading to numerical instabilities due to the negative viscosity. To remove the negative viscosity, the calculation of parameters in the DSM requires the averaging procedure in homogeneous directions of turbulent flows. Although this averaging procedure leads to numerical stability, more CPU time is required. In addition, under complex boundary conditions due to the flow control, e.g. wall deformation, the averaging procedure in the homogeneous directions is not reasonable. The validation of SGS models has been examined mainly in terms of uncontrolled canonical flows such as channel and boundary-layer flows. Although there are some LES studies on controlled flows (e.g. Chang, Collis & Ramakrishnan Reference Chang, Collis and Ramakrishnan2002), a detailed assessment of SGS models for controlled flows has not yet been realized.

On the basis of the above-mentioned background, the main objective of our present study is to investigate the drag reduction effect of streamwise travelling wave-like wall deformation in a turbulent channel flow at high Reynolds numbers of the order of ![]() $Re_\tau \sim 10^3$ by using LES. First, we assess SGS models for the LES of a turbulent channel flow controlled using the streamwise travelling wave generated by wall deformation at low to moderate Reynolds numbers, i.e.

$Re_\tau \sim 10^3$ by using LES. First, we assess SGS models for the LES of a turbulent channel flow controlled using the streamwise travelling wave generated by wall deformation at low to moderate Reynolds numbers, i.e. ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ and

$Re_\tau = 360$ and ![]() $720$. Subsequently, we investigate the drag reduction effect of streamwise travelling wave-like wall deformation at higher Reynolds numbers, i.e.

$720$. Subsequently, we investigate the drag reduction effect of streamwise travelling wave-like wall deformation at higher Reynolds numbers, i.e. ![]() $Re_\tau = 1080$,

$Re_\tau = 1080$, ![]() $2160$ and

$2160$ and ![]() $3240$.

$3240$.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The numerical methods for the present LES and DNS are summarized in § 2. In § 3, we discuss the behaviour of several SGS models in a turbulent channel flow controlled using the streamwise travelling wave generated by wall deformation at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ and

$Re_\tau = 360$ and ![]() $720$, and we compare it with the DNS results (Nabae et al. Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020). In addition, we discuss the turbulent structures that are important for assessing the reproduction of the controlled flow. In § 4, we investigate the drag reduction effect of this control in high-Reynolds-number turbulent channel flows, i.e.

$720$, and we compare it with the DNS results (Nabae et al. Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020). In addition, we discuss the turbulent structures that are important for assessing the reproduction of the controlled flow. In § 4, we investigate the drag reduction effect of this control in high-Reynolds-number turbulent channel flows, i.e. ![]() $Re_\tau = 1080$,

$Re_\tau = 1080$, ![]() $2160$ and

$2160$ and ![]() $3240$. Finally, we conclude the present study in § 5.

$3240$. Finally, we conclude the present study in § 5.

2. Numerical methods

2.1. Governing equation

The governing equations for LES are the filtered incompressible continuity and Navier–Stokes equations:

where ![]() $u_i~( i=1,2,3 )$ and

$u_i~( i=1,2,3 )$ and ![]() $p$ denote the filtered velocity components and pressure, respectively, and

$p$ denote the filtered velocity components and pressure, respectively, and ![]() $\tau _{ij}$ is the SGS stress, which must be modelled to close the equations. The details of

$\tau _{ij}$ is the SGS stress, which must be modelled to close the equations. The details of ![]() $\tau _{ij}$ are described later. All variables are made dimensionless by the fluid density

$\tau _{ij}$ are described later. All variables are made dimensionless by the fluid density ![]() $\rho ^*$, the friction velocity

$\rho ^*$, the friction velocity ![]() $u_\tau ^*$ and the channel half-width

$u_\tau ^*$ and the channel half-width ![]() $\delta ^*$, where the superscript * denotes dimensional quantities. The friction Reynolds number is defined as

$\delta ^*$, where the superscript * denotes dimensional quantities. The friction Reynolds number is defined as ![]() $Re_\tau = u_\tau ^* \delta ^* / \nu ^*$, where

$Re_\tau = u_\tau ^* \delta ^* / \nu ^*$, where ![]() $\nu ^*$ is the kinematic viscosity. The fourth term on the right-hand side of (2.2) representing the mean pressure gradient is

$\nu ^*$ is the kinematic viscosity. The fourth term on the right-hand side of (2.2) representing the mean pressure gradient is ![]() $- ( {\rm d}P/{\rm d}\kern0.7pt x_1 ) = 1$. Hereafter, for convenience,

$- ( {\rm d}P/{\rm d}\kern0.7pt x_1 ) = 1$. Hereafter, for convenience, ![]() $(x_1,x_2,x_3)$ and

$(x_1,x_2,x_3)$ and ![]() $(u_1,u_2,u_3)$ are interchangeably denoted by

$(u_1,u_2,u_3)$ are interchangeably denoted by ![]() $(x,y,z)$ and

$(x,y,z)$ and ![]() $(u,v,w)$, respectively.

$(u,v,w)$, respectively.

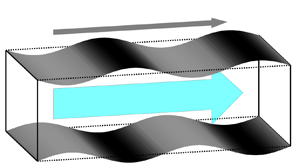

Figure 1 shows a schematic of a turbulent channel flow with streamwise travelling wave-like wall deformation. To compute the continuous deforming wall accurately, we utilize the coordinate transformation proposed by Kang & Choi (Reference Kang and Choi2000):

where ![]() $\xi _1$,

$\xi _1$, ![]() $\xi _2$ and

$\xi _2$ and ![]() $\xi _3$ are the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise directions in computational space, respectively, and

$\xi _3$ are the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise directions in computational space, respectively, and ![]() $\eta = ( \eta _u - \eta _d ) / 2$ with

$\eta = ( \eta _u - \eta _d ) / 2$ with ![]() $\eta _u$ and

$\eta _u$ and ![]() $\eta _d$ denoting the displacements of the upper and lower walls, respectively. Similarly to previous studies (Nakanishi et al. Reference Nakanishi, Mamori and Fukagata2012; Nabae et al. Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020; Nabae & Fukagata Reference Nabae and Fukagata2021), we apply the spanwise-uniform streamwise travelling wave; thus,

$\eta _d$ denoting the displacements of the upper and lower walls, respectively. Similarly to previous studies (Nakanishi et al. Reference Nakanishi, Mamori and Fukagata2012; Nabae et al. Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020; Nabae & Fukagata Reference Nabae and Fukagata2021), we apply the spanwise-uniform streamwise travelling wave; thus, ![]() $\eta _d$ and

$\eta _d$ and ![]() $\eta _u$ are defined as

$\eta _u$ are defined as

For the surface motion, we consider the varicose mode, in which the upper and lower walls are moved in phase with the opposite sign. The control parameters used to determine the surface motion are the velocity amplitude ![]() $a$, the streamwise wavenumber

$a$, the streamwise wavenumber ![]() $k$ and the phase speed

$k$ and the phase speed ![]() $c$. In this study, the combination of these control parameters is set to

$c$. In this study, the combination of these control parameters is set to ![]() $( a^+,k^+,c^+ ) = ( 10,0.022,30 )$, which is the maximum drag reduction case in the paper by Nabae et al. (Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020). Hereafter, a superscript ‘

$( a^+,k^+,c^+ ) = ( 10,0.022,30 )$, which is the maximum drag reduction case in the paper by Nabae et al. (Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020). Hereafter, a superscript ‘![]() $+$’ denotes wall units.

$+$’ denotes wall units.

Figure 1. Schematic of a turbulent channel flow with streamwise travelling wave-like wall deformation.

As a result of this coordinate transformation, the filtered continuity and Navier–Stokes equations in the boundary-fitted coordinates of (2.3a–c) are respectively expressed as

where ![]() $S_c$ and

$S_c$ and ![]() $S_i$ are the source terms due to the coordinate transformation:

$S_i$ are the source terms due to the coordinate transformation:

\begin{align} S_i &={-}\psi_t \frac{\partial u_i}{\partial \xi_2} - \varphi^\prime_j \frac{\partial \left( u_i u_j \right)}{\partial \xi_2} - \varphi^\prime_i \frac{\partial p}{\partial \xi_2} \nonumber\\ &\quad +\frac{1}{ \textit{Re}_\tau } \left \{ 2\varphi^\prime_j \frac{\partial^2 u_i}{\partial \xi_j \partial \xi_2} + \varphi^\prime_j \varphi^\prime_j \frac{\partial^2 u_i}{\partial \xi_2 \partial \xi_2} + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial \left( \varphi^\prime_j \varphi^\prime_j \right)}{\partial \xi_2} \frac{\partial u_i}{\partial \xi_2} + \frac{\partial \varphi^\prime_j}{\partial \xi_j} \frac{\partial u_i}{\partial \xi_2} \right \}, \end{align}

\begin{align} S_i &={-}\psi_t \frac{\partial u_i}{\partial \xi_2} - \varphi^\prime_j \frac{\partial \left( u_i u_j \right)}{\partial \xi_2} - \varphi^\prime_i \frac{\partial p}{\partial \xi_2} \nonumber\\ &\quad +\frac{1}{ \textit{Re}_\tau } \left \{ 2\varphi^\prime_j \frac{\partial^2 u_i}{\partial \xi_j \partial \xi_2} + \varphi^\prime_j \varphi^\prime_j \frac{\partial^2 u_i}{\partial \xi_2 \partial \xi_2} + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial \left( \varphi^\prime_j \varphi^\prime_j \right)}{\partial \xi_2} \frac{\partial u_i}{\partial \xi_2} + \frac{\partial \varphi^\prime_j}{\partial \xi_j} \frac{\partial u_i}{\partial \xi_2} \right \}, \end{align}with

and

\begin{equation} \varphi_j = \left \{\begin{array}{@{}ll@{}} \displaystyle{ -\dfrac{1}{1+\eta} \left( \dfrac{\partial \eta_d}{\partial \xi_j} + \xi_2 \dfrac{\partial \eta}{\partial \xi_j} \right) } & {\rm for}\ j=1,3, \\ \displaystyle{ \dfrac{1}{1+\eta} } & {\rm for}\ j=2. \end{array}\right. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \varphi_j = \left \{\begin{array}{@{}ll@{}} \displaystyle{ -\dfrac{1}{1+\eta} \left( \dfrac{\partial \eta_d}{\partial \xi_j} + \xi_2 \dfrac{\partial \eta}{\partial \xi_j} \right) } & {\rm for}\ j=1,3, \\ \displaystyle{ \dfrac{1}{1+\eta} } & {\rm for}\ j=2. \end{array}\right. \end{equation}In addition, the SGS terms are transformed as follows:

\begin{align} T_i &= \frac{\partial \tau_{ij}}{\partial x_j} \nonumber\\ &= \frac{\partial \tau_{ij}}{\partial \xi_k} \frac{\partial \xi_k}{\partial x_j} \nonumber\\ &= \left \{\begin{array}{@{}ll@{}} \displaystyle{ \dfrac{\partial \tau_{ij}}{\partial \xi_j} - \dfrac{\partial \tau_{ij}}{\partial \xi_2} \dfrac{1}{1+\eta} \left( \dfrac{\partial \eta_d}{\partial \xi_j} + \xi_2 \dfrac{\partial \eta}{\partial \xi_j} \right) } & {\rm for}\ j=1,3, \\ \displaystyle{ \dfrac{\partial \tau_{ij}}{\partial \xi_j} \dfrac{1}{1+\eta} } & {\rm for}\ j=2. \end{array} \right. \end{align}

\begin{align} T_i &= \frac{\partial \tau_{ij}}{\partial x_j} \nonumber\\ &= \frac{\partial \tau_{ij}}{\partial \xi_k} \frac{\partial \xi_k}{\partial x_j} \nonumber\\ &= \left \{\begin{array}{@{}ll@{}} \displaystyle{ \dfrac{\partial \tau_{ij}}{\partial \xi_j} - \dfrac{\partial \tau_{ij}}{\partial \xi_2} \dfrac{1}{1+\eta} \left( \dfrac{\partial \eta_d}{\partial \xi_j} + \xi_2 \dfrac{\partial \eta}{\partial \xi_j} \right) } & {\rm for}\ j=1,3, \\ \displaystyle{ \dfrac{\partial \tau_{ij}}{\partial \xi_j} \dfrac{1}{1+\eta} } & {\rm for}\ j=2. \end{array} \right. \end{align} The periodic boundary conditions are applied in the streamwise ![]() $( \xi _1 )$ and spanwise

$( \xi _1 )$ and spanwise ![]() $( \xi _3 )$ directions. When considering the coordinate transformation associated with the wall deformation, the no-slip velocity boundary conditions on the upper and lower walls lead to

$( \xi _3 )$ directions. When considering the coordinate transformation associated with the wall deformation, the no-slip velocity boundary conditions on the upper and lower walls lead to

\begin{equation} \left \{\begin{array}{@{}ll@{}} u_1 = u_3 = 0,~u_2 = \displaystyle{ \dfrac{\partial \eta_u}{\partial t} } ={-}a \cos \left \{ k \left( \xi_1 - ct \right) \right \} & {\rm (upper~wall),} \\[10pt] u_1 = u_3 = 0,~u_2 = \displaystyle{ \dfrac{\partial \eta_d}{\partial t} } = a \cos \left \{ k \left( \xi_1 - ct \right) \right \} & {\rm (lower~wall).} \end{array} \right. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left \{\begin{array}{@{}ll@{}} u_1 = u_3 = 0,~u_2 = \displaystyle{ \dfrac{\partial \eta_u}{\partial t} } ={-}a \cos \left \{ k \left( \xi_1 - ct \right) \right \} & {\rm (upper~wall),} \\[10pt] u_1 = u_3 = 0,~u_2 = \displaystyle{ \dfrac{\partial \eta_d}{\partial t} } = a \cos \left \{ k \left( \xi_1 - ct \right) \right \} & {\rm (lower~wall).} \end{array} \right. \end{equation}2.2. Subgrid-scale models

In the present LES, ![]() $\tau _{ij}$ is modelled on the basis of the eddy-viscosity assumption as

$\tau _{ij}$ is modelled on the basis of the eddy-viscosity assumption as

where ![]() $\nu _t$ denotes the SGS eddy viscosity and

$\nu _t$ denotes the SGS eddy viscosity and ![]() $s_{ij}$ is the strain-rate tensor, i.e.

$s_{ij}$ is the strain-rate tensor, i.e. ![]() $s_{ij} = ( \partial u_j / \partial x_i + \partial u_i / \partial x_j ) / 2$. The SGS eddy viscosity

$s_{ij} = ( \partial u_j / \partial x_i + \partial u_i / \partial x_j ) / 2$. The SGS eddy viscosity ![]() $\nu _t$ should be modelled in LES. However, in an incompressible flow,

$\nu _t$ should be modelled in LES. However, in an incompressible flow, ![]() $\tau _{kk}$ does not need to be modelled because it is solved with pressure as

$\tau _{kk}$ does not need to be modelled because it is solved with pressure as ![]() $p + \tau _{kk} / 3$. The SGS models used in this study are summarized below.

$p + \tau _{kk} / 3$. The SGS models used in this study are summarized below.

2.2.1. Smagorinsky model

The Smagorinsky model (Smagorinsky Reference Smagorinsky1963) is the most classical SGS model expressed as

where ![]() $S^2 = s_{ij} s_{ij}$ and the Smagorinsky constant

$S^2 = s_{ij} s_{ij}$ and the Smagorinsky constant ![]() $C_s$ is set to

$C_s$ is set to ![]() $0.1$ for turbulent channel flows (Pope Reference Pope2000). The filter width

$0.1$ for turbulent channel flows (Pope Reference Pope2000). The filter width ![]() $\bar {\varDelta }$ is given by the geometric mean, i.e.

$\bar {\varDelta }$ is given by the geometric mean, i.e. ![]() $\bar {\varDelta } = ( \Delta \xi _1 \Delta \xi _2 \Delta \xi _3 )^{1/3}$, where

$\bar {\varDelta } = ( \Delta \xi _1 \Delta \xi _2 \Delta \xi _3 )^{1/3}$, where ![]() $\Delta \xi _i$ is the grid spacing in the

$\Delta \xi _i$ is the grid spacing in the ![]() $i$th direction. The near-wall damping function

$i$th direction. The near-wall damping function ![]() $f_v$ is introduced to decrease the excessive SGS stress in the region near the wall. In this study, we consider the damping function used by Hwang & Cossu (Reference Hwang and Cossu2010):

$f_v$ is introduced to decrease the excessive SGS stress in the region near the wall. In this study, we consider the damping function used by Hwang & Cossu (Reference Hwang and Cossu2010):

\begin{equation} f_v = 1-\exp \left[ - \left( \frac{y_d^+}{A^+} \right)^3 \right], \end{equation}

\begin{equation} f_v = 1-\exp \left[ - \left( \frac{y_d^+}{A^+} \right)^3 \right], \end{equation}

where ![]() $y_d$ is the distance from the wall in computational space and

$y_d$ is the distance from the wall in computational space and ![]() $A^+ = 25$. In general, the classical van Driest damping function, i.e.

$A^+ = 25$. In general, the classical van Driest damping function, i.e. ![]() $f_v = [ 1-\exp ( -y_d^+ / A^+ ) ]^2$, has been widely used as a damping function. However, according to our preliminary test in a sufficiently high-grid-resolution case (HR case, explained later), the Smagorinsky model using (2.16) predicts the drag reduction rate in DNS better than that predicted using the classical van Driest damping function (see Appendix A for details). Therefore, in this study, we utilize (2.16) as a damping function.

$f_v = [ 1-\exp ( -y_d^+ / A^+ ) ]^2$, has been widely used as a damping function. However, according to our preliminary test in a sufficiently high-grid-resolution case (HR case, explained later), the Smagorinsky model using (2.16) predicts the drag reduction rate in DNS better than that predicted using the classical van Driest damping function (see Appendix A for details). Therefore, in this study, we utilize (2.16) as a damping function.

2.2.2. The WALE model

The WALE model (Nicoud & Ducros Reference Nicoud and Ducros1999) is based on the square of the velocity gradient tensor, and the SGS eddy viscosity is modelled as

\begin{equation} \nu_t = f_v \left( C_w \bar{\varDelta} \right)^2 \frac{ \left( s_{ij}^d s_{ij}^d \right)^{3/2} }{ \left( s_{ij} s_{ij} \right)^{5/2} + \left( s_{ij}^d s_{ij}^d \right)^{5/4} }. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \nu_t = f_v \left( C_w \bar{\varDelta} \right)^2 \frac{ \left( s_{ij}^d s_{ij}^d \right)^{3/2} }{ \left( s_{ij} s_{ij} \right)^{5/2} + \left( s_{ij}^d s_{ij}^d \right)^{5/4} }. \end{equation}

The square of the traceless symmetric part of the velocity gradient tensor, ![]() $s_{ij}^d s_{ij}^d$, is computed as

$s_{ij}^d s_{ij}^d$, is computed as

with ![]() $\varOmega ^2 = \omega _{ij} \omega _{ij}$ and

$\varOmega ^2 = \omega _{ij} \omega _{ij}$ and ![]() $IV_{S \varOmega } = s_{ik} s_{kj} \omega _{jl} \omega _{li}$, where

$IV_{S \varOmega } = s_{ik} s_{kj} \omega _{jl} \omega _{li}$, where ![]() $\omega _{ij}$ is the rotation tensor, i.e.

$\omega _{ij}$ is the rotation tensor, i.e. ![]() $\omega _{ij} = ( \partial u_j / \partial x_i - \partial u_i / \partial x_j ) / 2$. The constant

$\omega _{ij} = ( \partial u_j / \partial x_i - \partial u_i / \partial x_j ) / 2$. The constant ![]() $C_w$ is set to

$C_w$ is set to ![]() $0.5$. Here, we introduce an additional damping function

$0.5$. Here, we introduce an additional damping function ![]() $f_v$ of (2.16) to the WALE model because the original WALE model where

$f_v$ of (2.16) to the WALE model because the original WALE model where ![]() $f_v = 1$ does not reproduce the decrease in eddy viscosity in the near-wall region when considering the travelling wave generated by wall deformation (see Appendices A and B).

$f_v = 1$ does not reproduce the decrease in eddy viscosity in the near-wall region when considering the travelling wave generated by wall deformation (see Appendices A and B).

2.3. Numerical schemes and conditions

The LES code in this study is based on the DNS code for an uncontrolled turbulent channel flow developed in previous studies (Fukagata, Kasagi & Koumoutsakos Reference Fukagata, Kasagi and Koumoutsakos2006; Nabae & Fukagata Reference Nabae and Fukagata2024) and that used by Nabae et al. (Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020), who performed the DNS of a turbulent channel flow controlled using the spanwise-uniform travelling wave generated by wall deformation under the CPG condition. The governing equations are spatially discretized using the energy-conserving fourth-order finite-difference scheme (Morinishi et al. Reference Morinishi, Lund, Vasilyev and Moin1998) in the streamwise and spanwise directions and the second-order finite-difference scheme in the wall-normal direction on the staggered grid system. For time integration, we utilize the low-storage, third-order Runge–Kutta/Crank–Nicolson scheme (Spalart, Moser & Rogers Reference Spalart, Moser and Rogers1991) with the high-order SMAC-like velocity–pressure coupling scheme (Dukowicz & Dvinsky Reference Dukowicz and Dvinsky1992). The pressure Poisson equation is solved by a two-dimensional fast Fourier transform in the streamwise and spanwise directions and using the tridiagonal matrix algorithm in the wall-normal direction.

Similarly to Nabae et al. (Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020), all simulations in this study are performed under CPG conditions because the near-wall scaling is of great importance for predicting the drag reduction rate by the modelling of the mean velocity profile. We consider five different friction Reynolds numbers, i.e. ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$,

$Re_\tau = 360$, ![]() $720$,

$720$, ![]() $1080$,

$1080$, ![]() $2160$ and

$2160$ and ![]() $3240$. The computational conditions are shown in table 1, where

$3240$. The computational conditions are shown in table 1, where ![]() $L_i$ and

$L_i$ and ![]() $N_i$ denote the length of the computational domain and the number of grid points, respectively, in the

$N_i$ denote the length of the computational domain and the number of grid points, respectively, in the ![]() $i$th direction. In table 1, ‘no model’ represents the simulations without using any SGS models.

$i$th direction. In table 1, ‘no model’ represents the simulations without using any SGS models.

Table 1. Computational conditions in all cases.

All simulations at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ are classified into four different categories on the basis of grid resolution and domain size: the ZHR, XHR, HR and HR-SD cases. Cases ZHR and XHR represent higher grid resolutions in the

$Re_\tau = 360$ are classified into four different categories on the basis of grid resolution and domain size: the ZHR, XHR, HR and HR-SD cases. Cases ZHR and XHR represent higher grid resolutions in the ![]() $z$ and

$z$ and ![]() $x$ directions, respectively: in the ZHR case,

$x$ directions, respectively: in the ZHR case, ![]() $( \Delta x^+,\Delta z^+ ) = ( 35.3,17.7 )$; in the XHR case,

$( \Delta x^+,\Delta z^+ ) = ( 35.3,17.7 )$; in the XHR case, ![]() $( \Delta x^+,\Delta z^+ ) = ( 23.6,23.6 )$. Case HR represents higher grid resolution in both the

$( \Delta x^+,\Delta z^+ ) = ( 23.6,23.6 )$. Case HR represents higher grid resolution in both the ![]() $x$ and

$x$ and ![]() $z$ directions, i.e.

$z$ directions, i.e. ![]() $( \Delta x^+,\Delta z^+ ) = ( 23.6,17.7 )$. The numbers of grid points in the streamwise direction per wave,

$( \Delta x^+,\Delta z^+ ) = ( 23.6,17.7 )$. The numbers of grid points in the streamwise direction per wave, ![]() $N_w$, are

$N_w$, are ![]() $N_w = 8$,

$N_w = 8$, ![]() $12$ and

$12$ and ![]() $12$ in the ZHR, XHR and HR cases, respectively, whereas

$12$ in the ZHR, XHR and HR cases, respectively, whereas ![]() $N_w = 32$ in DNS (Nabae et al. Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020). In addition, the computational domain in the ZHR, XHR and HR cases is

$N_w = 32$ in DNS (Nabae et al. Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020). In addition, the computational domain in the ZHR, XHR and HR cases is ![]() $( L_x,L_y,L_z ) = ( 2{\rm \pi},2,{\rm \pi} )$, whereas in the HR-SD case it is

$( L_x,L_y,L_z ) = ( 2{\rm \pi},2,{\rm \pi} )$, whereas in the HR-SD case it is ![]() $( L_x,L_y,L_z ) = ( {\rm \pi},2,0.5{\rm \pi} )$. At

$( L_x,L_y,L_z ) = ( {\rm \pi},2,0.5{\rm \pi} )$. At ![]() $Re_\tau = 720$, we perform the simulations in the HR and HR-SD cases. At higher Reynolds numbers, i.e.

$Re_\tau = 720$, we perform the simulations in the HR and HR-SD cases. At higher Reynolds numbers, i.e. ![]() $Re_\tau = 1080$,

$Re_\tau = 1080$, ![]() $2160$ and

$2160$ and ![]() $3240$, we perform only one simulation in the HR-SD case at each friction Reynolds number.

$3240$, we perform only one simulation in the HR-SD case at each friction Reynolds number.

2.4. Drag reduction rate

We define the drag reduction rate ![]() $R_D$ as

$R_D$ as

where ![]() $C_D$ and

$C_D$ and ![]() $C_{D,{NC}}$ represent the drag coefficients in the controlled and uncontrolled cases, respectively. In the controlled case,

$C_{D,{NC}}$ represent the drag coefficients in the controlled and uncontrolled cases, respectively. In the controlled case, ![]() $C_D$ can be computed as

$C_D$ can be computed as ![]() $C_D = 2 / {U_b^+}^2$, where

$C_D = 2 / {U_b^+}^2$, where ![]() $U_b^+$ is the resultant bulk-mean velocity. In this study, we perform LES under CPG conditions, so that the bulk-mean velocity is changed by the control. Therefore,

$U_b^+$ is the resultant bulk-mean velocity. In this study, we perform LES under CPG conditions, so that the bulk-mean velocity is changed by the control. Therefore, ![]() $C_{D,{NC}}$ at the resultant bulk Reynolds number of each controlled case is computed as

$C_{D,{NC}}$ at the resultant bulk Reynolds number of each controlled case is computed as

\begin{equation} C_{D,{NC}} = \frac{2}{{U_{b,{NC}}^+}^2}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} C_{D,{NC}} = \frac{2}{{U_{b,{NC}}^+}^2}, \end{equation}

where ![]() $U_{b,{NC}}^+$ denotes the bulk-mean velocity of the uncontrolled flow, which can be predicted using the approximation equation (Nabae et al. Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020):

$U_{b,{NC}}^+$ denotes the bulk-mean velocity of the uncontrolled flow, which can be predicted using the approximation equation (Nabae et al. Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020):

The bulk Reynolds number ![]() $Re_b$ can be calculated as

$Re_b$ can be calculated as ![]() $Re_b = 2U_b^* \delta ^* / \nu ^* = 2U_b^+ \textit {Re}_\tau$. Note that the accuracy of (2.21) has been confirmed in our previous studies (Nabae et al. Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020; Nabae & Fukagata Reference Nabae and Fukagata2021, Reference Nabae and Fukagata2022).

$Re_b = 2U_b^* \delta ^* / \nu ^* = 2U_b^+ \textit {Re}_\tau$. Note that the accuracy of (2.21) has been confirmed in our previous studies (Nabae et al. Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020; Nabae & Fukagata Reference Nabae and Fukagata2021, Reference Nabae and Fukagata2022).

3. Assessment of SGS models at low to moderate Reynolds numbers

3.1. Turbulence statistics

In the present problem setting, the periodic component generated by the travelling wave is included in the statistics. To distinguish the periodic component from the turbulent component, the three-component decomposition (Hussain & Reynolds Reference Hussain and Reynolds1970), i.e.

is utilized. Here, ![]() $f$ is an arbitrary function and

$f$ is an arbitrary function and ![]() $\phi _x$ is the phase of the wave in the streamwise direction defined as

$\phi _x$ is the phase of the wave in the streamwise direction defined as ![]() $2 n {\rm \pi}+ \phi _x = k ( x - ct )$, where

$2 n {\rm \pi}+ \phi _x = k ( x - ct )$, where ![]() $n$ is an integer and

$n$ is an integer and ![]() $0 \leqslant \phi _x < 2{\rm \pi}$. The overbar represents the mean component averaged in the streamwise

$0 \leqslant \phi _x < 2{\rm \pi}$. The overbar represents the mean component averaged in the streamwise ![]() $( x )$ and spanwise

$( x )$ and spanwise ![]() $( z )$ directions and time. The tilde represents the periodic component, i.e.

$( z )$ directions and time. The tilde represents the periodic component, i.e.

where ![]() $\langle\, f \rangle (\phi _x,y )$ is the phase-averaged quantity. In addition, the double prime represents the turbulent component. The total fluctuation components correspond to the summation of the periodic and turbulent components, i.e.

$\langle\, f \rangle (\phi _x,y )$ is the phase-averaged quantity. In addition, the double prime represents the turbulent component. The total fluctuation components correspond to the summation of the periodic and turbulent components, i.e.

When there is no periodic component in the uncontrolled case, ![]() $f^\prime ( x,y,z,t ) = f^{\prime \prime } ( x,y,z,t )$. The phase-averaged and mean components in (3.2) are calculated as

$f^\prime ( x,y,z,t ) = f^{\prime \prime } ( x,y,z,t )$. The phase-averaged and mean components in (3.2) are calculated as

$$\begin{gather} \langle\, f \rangle \left(\phi_x,y \right) = \frac{1}{N_{\phi_x}} \sum_{ x \in N_{\phi_x} } \left[ \frac{1}{L_3 T} \int_0^{L_3} \int_0^T f \left( x,y,z,t \right) {\rm d}t\,{\rm d}z \right], \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather} \langle\, f \rangle \left(\phi_x,y \right) = \frac{1}{N_{\phi_x}} \sum_{ x \in N_{\phi_x} } \left[ \frac{1}{L_3 T} \int_0^{L_3} \int_0^T f \left( x,y,z,t \right) {\rm d}t\,{\rm d}z \right], \end{gather}$$

where ![]() $N_{\phi _x} = k L_x / (2{\rm \pi} )$ is the number of streamwise locations belonging to the same phase.

$N_{\phi _x} = k L_x / (2{\rm \pi} )$ is the number of streamwise locations belonging to the same phase.

In the uncontrolled case, the present LES can well reproduce the mean velocity profile at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ and

$Re_\tau = 360$ and ![]() $720$ regardless of SGS model and grid resolution. However, focusing on controlled cases with lower grid resolutions, i.e. ZHR and XHR cases, LES fails to reproduce the mean velocity profile obtained by DNS, leading to a relatively large difference between the drag reduction rate in LES and in DNS. Thus, for LES, the grid resolution in the ZHR and XHR cases is not sufficient for predicting the turbulence statistics in the controlled case (see Appendix B for details).

$720$ regardless of SGS model and grid resolution. However, focusing on controlled cases with lower grid resolutions, i.e. ZHR and XHR cases, LES fails to reproduce the mean velocity profile obtained by DNS, leading to a relatively large difference between the drag reduction rate in LES and in DNS. Thus, for LES, the grid resolution in the ZHR and XHR cases is not sufficient for predicting the turbulence statistics in the controlled case (see Appendix B for details).

On the basis of the assessment results in the ZHR and XHR cases, we further assess the SGS models in the controlled flows at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ by using a finer grid resolution, i.e. the HR case. To reproduce a reasonable decay of SGS eddy viscosity in the controlled case, we apply the damping function of (2.16) to not only the Smagorinsky model but also the WALE model. Furthermore, to investigate the Reynolds number dependence, we assess the SGS models in the controlled flows at a higher Reynolds number, i.e.

$Re_\tau = 360$ by using a finer grid resolution, i.e. the HR case. To reproduce a reasonable decay of SGS eddy viscosity in the controlled case, we apply the damping function of (2.16) to not only the Smagorinsky model but also the WALE model. Furthermore, to investigate the Reynolds number dependence, we assess the SGS models in the controlled flows at a higher Reynolds number, i.e. ![]() $Re_\tau = 720$. Figures 2 and 3 show the turbulence statistics of the controlled flows in the HR case at

$Re_\tau = 720$. Figures 2 and 3 show the turbulence statistics of the controlled flows in the HR case at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ and

$Re_\tau = 360$ and ![]() $720$, where figure 3 shows the profiles obtained using the WALE model with the damping function compared with those obtained by DNS. The drag reduction rate

$720$, where figure 3 shows the profiles obtained using the WALE model with the damping function compared with those obtained by DNS. The drag reduction rate ![]() $R_D$ in each case is shown in table 2. Note that ‘error’ in tables 2–5 is calculated as

$R_D$ in each case is shown in table 2. Note that ‘error’ in tables 2–5 is calculated as ![]() $R_{D,{LES}} - R_{D,{DNS}}$, where

$R_{D,{LES}} - R_{D,{DNS}}$, where ![]() $R_{D,{LES}}$ and

$R_{D,{LES}}$ and ![]() $R_{D,{DNS}}$ denote the drag reduction rates obtained by LES and DNS, respectively. Regardless of the friction Reynolds numbers, the Smagorinsky and WALE models can reproduce well the mean velocity profile obtained by DNS, such that the difference between the drag reduction rate in LES and that in DNS is very small. In the Smagorinsky and WALE models, i.e. S1HR360, W1HR360, S1HR720 and W1HR720, we find that the errors of the bulk-mean velocity in the uncontrolled and controlled cases are within

$R_{D,{DNS}}$ denote the drag reduction rates obtained by LES and DNS, respectively. Regardless of the friction Reynolds numbers, the Smagorinsky and WALE models can reproduce well the mean velocity profile obtained by DNS, such that the difference between the drag reduction rate in LES and that in DNS is very small. In the Smagorinsky and WALE models, i.e. S1HR360, W1HR360, S1HR720 and W1HR720, we find that the errors of the bulk-mean velocity in the uncontrolled and controlled cases are within ![]() $2\,\%$. In the case of no model, the mean velocity profile shifts downward in the buffer and logarithmic regions, leading to an underestimation of the drag reduction rate. Focusing on the turbulent root mean square (r.m.s.) of velocity fluctuations and turbulent Reynolds shear stress (RSS) in DNS, the control decreases

$2\,\%$. In the case of no model, the mean velocity profile shifts downward in the buffer and logarithmic regions, leading to an underestimation of the drag reduction rate. Focusing on the turbulent root mean square (r.m.s.) of velocity fluctuations and turbulent Reynolds shear stress (RSS) in DNS, the control decreases ![]() $u^{\prime \prime }_{rms}$ in the entire region of the channel, whereas

$u^{\prime \prime }_{rms}$ in the entire region of the channel, whereas ![]() $v^{\prime \prime }_{rms}$ and

$v^{\prime \prime }_{rms}$ and ![]() $w^{\prime \prime }_{rms}$ in the region near the wall are nearly unchanged or slightly increased compared with the uncontrolled case. In addition, the turbulent RSS significantly decreases in the region of

$w^{\prime \prime }_{rms}$ in the region near the wall are nearly unchanged or slightly increased compared with the uncontrolled case. In addition, the turbulent RSS significantly decreases in the region of ![]() $\xi _2^+ < 100$. The LES in the HR case can qualitatively well reproduce these trends. In summary, in turbulent channel flow with a complex time-dependent wall, it is of great importance to model the SGS shear stress in the region near the wall and to apply a relatively high grid resolution. For the present control method,

$\xi _2^+ < 100$. The LES in the HR case can qualitatively well reproduce these trends. In summary, in turbulent channel flow with a complex time-dependent wall, it is of great importance to model the SGS shear stress in the region near the wall and to apply a relatively high grid resolution. For the present control method, ![]() $12$ grid points per wave of wall deformation are required in the streamwise direction. In addition,

$12$ grid points per wave of wall deformation are required in the streamwise direction. In addition, ![]() $\Delta z^+ < 20$ is required in the spanwise direction similarly to the uncontrolled case (see e.g. Cimarelli & De Angelis Reference Cimarelli and De Angelis2012).

$\Delta z^+ < 20$ is required in the spanwise direction similarly to the uncontrolled case (see e.g. Cimarelli & De Angelis Reference Cimarelli and De Angelis2012).

Figure 2. Mean velocity profiles and turbulent RSS of the controlled flow in the HR case at (![]() $a$)

$a$) ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ and (

$Re_\tau = 360$ and (![]() $b$)

$b$) ![]() $Re_\tau = 720$: (i) mean velocity profile; (ii) RSS (grid scale + SGS, solid lines; SGS, dotted lines). In (ii), the grey line represents the profiles in the uncontrolled flow obtained by DNS.

$Re_\tau = 720$: (i) mean velocity profile; (ii) RSS (grid scale + SGS, solid lines; SGS, dotted lines). In (ii), the grey line represents the profiles in the uncontrolled flow obtained by DNS.

Figure 3. Turbulent r.m.s. velocity fluctuations of the controlled flows in the W1HR case at (![]() $a$)

$a$) ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ and (

$Re_\tau = 360$ and (![]() $b$)

$b$) ![]() $Re_\tau = 720$. Grey, DNS; green, WALE model with the damping function; dashed-dotted, uncontrolled; solid, controlled. To be easily viewable,

$Re_\tau = 720$. Grey, DNS; green, WALE model with the damping function; dashed-dotted, uncontrolled; solid, controlled. To be easily viewable, ![]() $2$ and

$2$ and ![]() $3$ are added to

$3$ are added to ![]() $v_{rms}$ and

$v_{rms}$ and ![]() $u_{rms}$, respectively.

$u_{rms}$, respectively.

Table 2. Drag reduction rate ![]() $R_D$ in the HR cases at

$R_D$ in the HR cases at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ and

$Re_\tau = 360$ and ![]() $720$.

$720$.

For further reduction in computational cost, we assess the SGS models in uncontrolled and controlled flows by using the smaller computational domain. As shown in figure 4, the difference between the turbulence statistics in the larger computational domain and in the smaller computational domain is very small, and the mean velocity profile in the smaller computational domain is in good agreement with that obtained by DNS. In addition, as summarized in table 3, the drag reduction rate in the smaller computational domain is in good agreement with not only that in the larger computational domain but also that obtained by DNS. Therefore, the smaller computational domain, i.e. ![]() $L_1 \times L_2 \times L_3 = {\rm \pi}\times 2 \times 0.5{\rm \pi}$, is sufficient for obtaining the drag reduction rate accurately; thus, we can perform the LES of controlled flows at a higher Reynolds number with a smaller numerical cost by using the smaller domain.

$L_1 \times L_2 \times L_3 = {\rm \pi}\times 2 \times 0.5{\rm \pi}$, is sufficient for obtaining the drag reduction rate accurately; thus, we can perform the LES of controlled flows at a higher Reynolds number with a smaller numerical cost by using the smaller domain.

Figure 4. Effect of computational domain on turbulence statistics of the (![]() $a$) uncontrolled and (

$a$) uncontrolled and (![]() $b$) controlled flows in the HR case at

$b$) controlled flows in the HR case at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ and

$Re_\tau = 360$ and ![]() $720$: (i) mean velocity profiles; (ii) RSS (grid scale + SGS, solid lines; SGS, dotted lines). To be easily viewable,

$720$: (i) mean velocity profiles; (ii) RSS (grid scale + SGS, solid lines; SGS, dotted lines). To be easily viewable, ![]() $15$ and

$15$ and ![]() $1$ are added to the mean velocity profile and RSS at

$1$ are added to the mean velocity profile and RSS at ![]() $Re_\tau = 720$, respectively.

$Re_\tau = 720$, respectively.

Table 3. Effect of the computational domain on the drag reduction rate ![]() $R_D$ at

$R_D$ at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ and

$Re_\tau = 360$ and ![]() $720$.

$720$.

3.2. Instantaneous flow structures

To assess the effects of the SGS model and grid resolution in the controlled flow in more detail, we investigate the instantaneous flow fields obtained by DNS and LES. Figures 5–8 show a comparison of the instantaneous streamwise and spanwise velocity fluctuations, ![]() $u^\prime$ and

$u^\prime$ and ![]() $w^\prime$, respectively, in the controlled flow at

$w^\prime$, respectively, in the controlled flow at ![]() $\xi _2^+ \approx 30$, which is around the peak of

$\xi _2^+ \approx 30$, which is around the peak of ![]() $\tau _{12}$ in the controlled case. In these figures, the black solid line represents the region where large-scale structures of

$\tau _{12}$ in the controlled case. In these figures, the black solid line represents the region where large-scale structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ exist. In addition, the black dashed line represents the region where many small-scale structures of

$u^\prime$ exist. In addition, the black dashed line represents the region where many small-scale structures of ![]() $w^\prime$ are generated, whereas the black dotted line represents the region where relatively large-scale structures are dominant. Hereafter, the regions represented by the black dashed and dotted lines are referred to as the active and quiescent regions, respectively.

$w^\prime$ are generated, whereas the black dotted line represents the region where relatively large-scale structures are dominant. Hereafter, the regions represented by the black dashed and dotted lines are referred to as the active and quiescent regions, respectively.

Figure 5 shows the effects of the SGS models on the instantaneous ![]() $u^\prime$ and

$u^\prime$ and ![]() $w^\prime$ in the controlled flow at

$w^\prime$ in the controlled flow at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ when the grid resolution in the HR case is applied. We compare the results obtained by DNS and those obtained using the Smagorinsky and WALE models with the damping function of (2.16). According to the DNS results shown in figure 5(i), we can observe the streamwise large-scale structures of

$Re_\tau = 360$ when the grid resolution in the HR case is applied. We compare the results obtained by DNS and those obtained using the Smagorinsky and WALE models with the damping function of (2.16). According to the DNS results shown in figure 5(i), we can observe the streamwise large-scale structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ (solid line region), whose length is more than twice the streamwise wavelength of the travelling wave, i.e. about

$u^\prime$ (solid line region), whose length is more than twice the streamwise wavelength of the travelling wave, i.e. about ![]() $600$ in wall units. In addition, many small-scale structures of

$600$ in wall units. In addition, many small-scale structures of ![]() $w^\prime$ are generated, and the active and quiescent regions of

$w^\prime$ are generated, and the active and quiescent regions of ![]() $w^\prime$ are formed simultaneously. That is, the travelling wave of wall deformation generates intermittent structures of

$w^\prime$ are formed simultaneously. That is, the travelling wave of wall deformation generates intermittent structures of ![]() $w^\prime$. The active regions of

$w^\prime$. The active regions of ![]() $w^\prime$ are formed in the areas where large-scale structures of

$w^\prime$ are formed in the areas where large-scale structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ exist, whereas the quiescent regions of

$u^\prime$ exist, whereas the quiescent regions of ![]() $w^\prime$ are formed in the areas where small-scale structures of

$w^\prime$ are formed in the areas where small-scale structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ whose length is comparable to the wavelength of the travelling wave are relatively dominant.

$u^\prime$ whose length is comparable to the wavelength of the travelling wave are relatively dominant.

Figure 5. Contours of instantaneous (![]() $a$)

$a$) ![]() $u^\prime$ and (

$u^\prime$ and (![]() $b$)

$b$) ![]() $w^\prime$ in the controlled flow at

$w^\prime$ in the controlled flow at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ when the grid resolution in the HR case is applied: (i) DNS; (ii) Smagorinsky model; (iii) WALE model with the damping function of (2.16). In (

$Re_\tau = 360$ when the grid resolution in the HR case is applied: (i) DNS; (ii) Smagorinsky model; (iii) WALE model with the damping function of (2.16). In (![]() $a$), the solid line denotes the streamwise large-scale structures of

$a$), the solid line denotes the streamwise large-scale structures of ![]() $u^\prime$. In (

$u^\prime$. In (![]() $b$), the dashed and dotted lines denote the active and quiescent regions of

$b$), the dashed and dotted lines denote the active and quiescent regions of ![]() $w^\prime$, respectively.

$w^\prime$, respectively.

In the case of using the Smagorinsky model (figure 5ii), the large-scale structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ and the small-scale structures of

$u^\prime$ and the small-scale structures of ![]() $w^\prime$ appear to be represented well, including the intermittent structures that are qualitatively similar to those obtained by DNS. In the case of using the WALE model, the large-scale structures of

$w^\prime$ appear to be represented well, including the intermittent structures that are qualitatively similar to those obtained by DNS. In the case of using the WALE model, the large-scale structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ and the small-scale structures of

$u^\prime$ and the small-scale structures of ![]() $w^\prime$ are fewer than those obtained using the Smagorinsky model. However, weak active and quiescent regions are present, such that we can observe weak intermittent structures of

$w^\prime$ are fewer than those obtained using the Smagorinsky model. However, weak active and quiescent regions are present, such that we can observe weak intermittent structures of ![]() $w^\prime$. These trends are observed in the case where the computational domain in the

$w^\prime$. These trends are observed in the case where the computational domain in the ![]() $x$ direction is doubled, i.e.

$x$ direction is doubled, i.e. ![]() $L_x = 4{\rm \pi}$ (see Appendix D for details). Figure 6 shows the effect of the grid resolution on the instantaneous

$L_x = 4{\rm \pi}$ (see Appendix D for details). Figure 6 shows the effect of the grid resolution on the instantaneous ![]() $u^\prime$ and

$u^\prime$ and ![]() $w^\prime$ in the controlled flow at

$w^\prime$ in the controlled flow at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ when the Smagorinsky model is applied. In the XHR and ZHR cases, the streamwise large-scale structures of

$Re_\tau = 360$ when the Smagorinsky model is applied. In the XHR and ZHR cases, the streamwise large-scale structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ are not clear and the active region of

$u^\prime$ are not clear and the active region of ![]() $w^\prime$ is smaller than that in the HR case. By applying a sufficiently high grid resolution, i.e.

$w^\prime$ is smaller than that in the HR case. By applying a sufficiently high grid resolution, i.e. ![]() $( \Delta x^+,\Delta z^+ ) = ( 23.6,17.7 )$, we find that LES can clearly reproduce the streamwise large-scale structures of

$( \Delta x^+,\Delta z^+ ) = ( 23.6,17.7 )$, we find that LES can clearly reproduce the streamwise large-scale structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ and intermittent structures of

$u^\prime$ and intermittent structures of ![]() $w^\prime$.

$w^\prime$.

Figure 6. Contours of instantaneous (![]() $a$)

$a$) ![]() $u^\prime$ and (

$u^\prime$ and (![]() $b$)

$b$) ![]() $w^\prime$ in the controlled flow at

$w^\prime$ in the controlled flow at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ when the Smagorinsky model is applied: (i) XHR case; (ii) ZHR case. The meaning of each line is the same as that in figure 5.

$Re_\tau = 360$ when the Smagorinsky model is applied: (i) XHR case; (ii) ZHR case. The meaning of each line is the same as that in figure 5.

Figure 7 shows the Reynolds number effect on the instantaneous ![]() $u^\prime$ and

$u^\prime$ and ![]() $w^\prime$ in the controlled flow when the grid resolution in the HR case is applied. The instantaneous structures of

$w^\prime$ in the controlled flow when the grid resolution in the HR case is applied. The instantaneous structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ and

$u^\prime$ and ![]() $w^\prime$ at

$w^\prime$ at ![]() $Re_\tau = 720$ are qualitatively similar to those at

$Re_\tau = 720$ are qualitatively similar to those at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$. In addition, these trends at

$Re_\tau = 360$. In addition, these trends at ![]() $Re_\tau = 720$ are stronger than those at

$Re_\tau = 720$ are stronger than those at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$. The WALE model sufficiently reproduces the intermittent structures of

$Re_\tau = 360$. The WALE model sufficiently reproduces the intermittent structures of ![]() $w^\prime$ with increasing Reynolds number. Thus, the drag reduction rate obtained using the WALE model is in very good agreement with that obtained by DNS.

$w^\prime$ with increasing Reynolds number. Thus, the drag reduction rate obtained using the WALE model is in very good agreement with that obtained by DNS.

Figure 7. Contours of instantaneous (![]() $a$)

$a$) ![]() $u^\prime$ and (

$u^\prime$ and (![]() $b$)

$b$) ![]() $w^\prime$ in the controlled flow at

$w^\prime$ in the controlled flow at ![]() $Re_\tau = 720$ when the grid resolution in the HR case is applied: (i) DNS; (ii) Smagorinsky model; (iii) WALE model with the damping function of (2.16). The meaning of each line is the same as that in figure 5.

$Re_\tau = 720$ when the grid resolution in the HR case is applied: (i) DNS; (ii) Smagorinsky model; (iii) WALE model with the damping function of (2.16). The meaning of each line is the same as that in figure 5.

Figure 8 shows the effect of the computational domain on the instantaneous ![]() $u^\prime$ and

$u^\prime$ and ![]() $w^\prime$ in the controlled flow at

$w^\prime$ in the controlled flow at ![]() $Re_\tau = 720$. In the HR-SD (i.e. small domain) case as well, the streamwise large-scale structures of

$Re_\tau = 720$. In the HR-SD (i.e. small domain) case as well, the streamwise large-scale structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ and the intermittent structures of

$u^\prime$ and the intermittent structures of ![]() $w^\prime$ are reproduced. Therefore, the drag reduction rate in the HR-SD case is in good agreement with that obtained by DNS.

$w^\prime$ are reproduced. Therefore, the drag reduction rate in the HR-SD case is in good agreement with that obtained by DNS.

Figure 8. Contours of instantaneous (a,c) ![]() $u^\prime$ and (b,d)

$u^\prime$ and (b,d) ![]() $w^\prime$ in the controlled flow for the (a,b) S1HR-SD720 case and (c,d) W1HR-SD720 case. The meaning of each line is the same as that in figure 5.

$w^\prime$ in the controlled flow for the (a,b) S1HR-SD720 case and (c,d) W1HR-SD720 case. The meaning of each line is the same as that in figure 5.

Furthermore, we compare the instantaneous vortical structures identified by using the ![]() $Q$ criterion (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Wray and Moin1988) at

$Q$ criterion (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Wray and Moin1988) at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ in figure 9. The number of vortical structures in all LES is smaller than that in the DNS. This is a natural consequence because the small-scale vortices are coarse-grained in LES. In the cases with lower spatial resolutions, i.e. S1XHR and S1ZHR cases, the vortical structures are insufficiently reproduced in the entire region of the channel. In the cases with higher spatial resolutions, i.e. S1HR360 and W1HR360, the vortical structures in the region near the wall are reasonably reproduced as compared with S1XHR and S1ZHR cases. Even in the small-computational-domain cases, i.e. S1SD and W1SD cases, the LES can reasonably reproduce the vortical structures in the region near the wall because relatively high spatial resolutions are applied. We can observe a similar trend at

$Re_\tau = 360$ in figure 9. The number of vortical structures in all LES is smaller than that in the DNS. This is a natural consequence because the small-scale vortices are coarse-grained in LES. In the cases with lower spatial resolutions, i.e. S1XHR and S1ZHR cases, the vortical structures are insufficiently reproduced in the entire region of the channel. In the cases with higher spatial resolutions, i.e. S1HR360 and W1HR360, the vortical structures in the region near the wall are reasonably reproduced as compared with S1XHR and S1ZHR cases. Even in the small-computational-domain cases, i.e. S1SD and W1SD cases, the LES can reasonably reproduce the vortical structures in the region near the wall because relatively high spatial resolutions are applied. We can observe a similar trend at ![]() $Re_\tau = 720$ (not shown here).

$Re_\tau = 720$ (not shown here).

Figure 9. Instantaneous vortical structures identified by using the ![]() $Q$ criterion (Hunt, Wray & Moin Reference Hunt, Wray and Moin1988) at

$Q$ criterion (Hunt, Wray & Moin Reference Hunt, Wray and Moin1988) at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$: (

$Re_\tau = 360$: (![]() $a$) DNS360; (

$a$) DNS360; (![]() $b$) S1XHR360; (

$b$) S1XHR360; (![]() $c$) S1ZHR360; (

$c$) S1ZHR360; (![]() $d$) S1HR360; (

$d$) S1HR360; (![]() $e$) W1HR360; (

$e$) W1HR360; (![]() $\,f$) S1SD360; (

$\,f$) S1SD360; (![]() $g$) W1SD360. The threshold is

$g$) W1SD360. The threshold is ![]() $Q^+ = 0.03$. Panels (

$Q^+ = 0.03$. Panels (![]() $a$–

$a$–![]() $e$) show a quarter of the full domain, i.e.

$e$) show a quarter of the full domain, i.e. ![]() $0 \leqq x \leqq {\rm \pi}$ and

$0 \leqq x \leqq {\rm \pi}$ and ![]() $0 \leqq z \leqq 0.5{\rm \pi}$. Here, (

$0 \leqq z \leqq 0.5{\rm \pi}$. Here, (![]() $a$) is redrawn using the data of Nabae et al. (Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020).

$a$) is redrawn using the data of Nabae et al. (Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020).

In summary, the key to reproducing the controlled turbulent flow is the formation of the large-scale structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ and the intermittent structures of

$u^\prime$ and the intermittent structures of ![]() $w^\prime$. The present LES applying relatively high grid resolutions, i.e.

$w^\prime$. The present LES applying relatively high grid resolutions, i.e. ![]() $\Delta x^+ \leqq 23.6$ and

$\Delta x^+ \leqq 23.6$ and ![]() $\Delta z^+ \leqq 17.7$, is sufficient for reproducing these key structures. The comparison of the instantaneous flow field between DNS and LES shows that the large-scale structures of

$\Delta z^+ \leqq 17.7$, is sufficient for reproducing these key structures. The comparison of the instantaneous flow field between DNS and LES shows that the large-scale structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ and the intermittent structures of

$u^\prime$ and the intermittent structures of ![]() $w^\prime$ are of great importance for the physical mechanism of drag reduction. Furthermore, compared with DNS (Nabae et al. Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020), we achieve a significant decrease in the number of grid points: the total numbers of grid points in the HR (HR-SD) cases at

$w^\prime$ are of great importance for the physical mechanism of drag reduction. Furthermore, compared with DNS (Nabae et al. Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020), we achieve a significant decrease in the number of grid points: the total numbers of grid points in the HR (HR-SD) cases at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ and

$Re_\tau = 360$ and ![]() $720$ are about

$720$ are about ![]() $1/16~(1/64)$ and

$1/16~(1/64)$ and ![]() $1/32~(1/128)$ of those obtained by DNS, respectively. Since the Smagorinsky and WALE models with the damping function can reasonably predict the controlled turbulent flow even for the above-mentioned decreased number of grid points, these models are judged sufficient for investigating the drag reduction effect at higher Reynolds numbers. In this study, we utilize the WALE model with the damping function in § 4 because it provides a better prediction of the drag reduction rate obtained by DNS than the Smagorinsky model.

$1/32~(1/128)$ of those obtained by DNS, respectively. Since the Smagorinsky and WALE models with the damping function can reasonably predict the controlled turbulent flow even for the above-mentioned decreased number of grid points, these models are judged sufficient for investigating the drag reduction effect at higher Reynolds numbers. In this study, we utilize the WALE model with the damping function in § 4 because it provides a better prediction of the drag reduction rate obtained by DNS than the Smagorinsky model.

4. Drag reduction effect at higher Reynolds numbers

On the basis of the results of assessment in § 3, we investigate the drag reduction effect of the streamwise travelling wave-like wall deformation in a turbulent channel flow at higher Reynolds numbers up to ![]() $Re_\tau = 3240$ by using the WALE model with the damping function of (2.16). Figure 10 shows the turbulence statistics in the controlled case compared with those in the uncontrolled case at

$Re_\tau = 3240$ by using the WALE model with the damping function of (2.16). Figure 10 shows the turbulence statistics in the controlled case compared with those in the uncontrolled case at ![]() $Re_\tau = 1080$,

$Re_\tau = 1080$, ![]() $2160$ and

$2160$ and ![]() $3240$. Note that the validation of the turbulence statistics in the uncontrolled flow at

$3240$. Note that the validation of the turbulence statistics in the uncontrolled flow at ![]() $Re_\tau = 1080\unicode{x2013}3240$ is shown in Appendix E. As shown in figure 10(i), in the viscous sublayer, the mean velocity profile in the controlled case is in good agreement with that in the uncontrolled case owing to the CPG condition, whereas in the buffer and logarithmic layers, it shifts upward owing to the wall deformation. Focusing on the turbulent r.m.s. of velocity fluctuations in figure 10(ii),

$Re_\tau = 1080\unicode{x2013}3240$ is shown in Appendix E. As shown in figure 10(i), in the viscous sublayer, the mean velocity profile in the controlled case is in good agreement with that in the uncontrolled case owing to the CPG condition, whereas in the buffer and logarithmic layers, it shifts upward owing to the wall deformation. Focusing on the turbulent r.m.s. of velocity fluctuations in figure 10(ii), ![]() $u^{\prime \prime }_{rms}$ is decreased in the entire region of the channel, whereas

$u^{\prime \prime }_{rms}$ is decreased in the entire region of the channel, whereas ![]() $v^{\prime \prime }_{rms}$ and

$v^{\prime \prime }_{rms}$ and ![]() $w^{\prime \prime }_{rms}$ in the region near the wall are nearly unchanged or slightly increased, compared with the uncontrolled case. As shown in figure 10(iii), the turbulent RSS for

$w^{\prime \prime }_{rms}$ in the region near the wall are nearly unchanged or slightly increased, compared with the uncontrolled case. As shown in figure 10(iii), the turbulent RSS for ![]() $\xi _2^+ < 100$ is significantly decreased regardless of the friction Reynolds number, leading to the large drag reduction effect. These trends of the turbulence statistics observed in figure 10 are qualitatively similar to those in the case of the lower Reynolds numbers, i.e.

$\xi _2^+ < 100$ is significantly decreased regardless of the friction Reynolds number, leading to the large drag reduction effect. These trends of the turbulence statistics observed in figure 10 are qualitatively similar to those in the case of the lower Reynolds numbers, i.e. ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ and

$Re_\tau = 360$ and ![]() $720$, as shown in figures 2 and 3.

$720$, as shown in figures 2 and 3.

Figure 10. Turbulence statistics in the uncontrolled (blue) and controlled (red) cases: (![]() $a$)

$a$) ![]() $Re_\tau = 1080$; (

$Re_\tau = 1080$; (![]() $b$)

$b$) ![]() $Re_\tau = 2160$; (

$Re_\tau = 2160$; (![]() $c$)

$c$) ![]() $Re_\tau = 3240$; (i) mean velocity profile; (ii) r.m.s. velocity fluctuations; (iii) RSS (grid scale + SGS, solid lines; SGS, dotted lines). To be easily viewable,

$Re_\tau = 3240$; (i) mean velocity profile; (ii) r.m.s. velocity fluctuations; (iii) RSS (grid scale + SGS, solid lines; SGS, dotted lines). To be easily viewable, ![]() $1.5$ and

$1.5$ and ![]() $2.5$ are added to

$2.5$ are added to ![]() $v_{rms}$ and

$v_{rms}$ and ![]() $u_{rms}$, respectively.

$u_{rms}$, respectively.

Figure 11 shows the instantaneous ![]() $u^\prime$ and

$u^\prime$ and ![]() $w^\prime$ in the controlled flow at

$w^\prime$ in the controlled flow at ![]() $Re_\tau = 1080$,

$Re_\tau = 1080$, ![]() $2160$ and

$2160$ and ![]() $3240$. Note that the meaning of each line is the same as that in figures 5–8. Even at high Reynolds numbers, structures obtained by LES are similar to those obtained by DNS at

$3240$. Note that the meaning of each line is the same as that in figures 5–8. Even at high Reynolds numbers, structures obtained by LES are similar to those obtained by DNS at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360$ and

$Re_\tau = 360$ and ![]() $720$. Namely, we can observe the streamwise large-scale structures of

$720$. Namely, we can observe the streamwise large-scale structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ (solid line region) and the intermittent structures of

$u^\prime$ (solid line region) and the intermittent structures of ![]() $w^\prime$ also in higher-Reynolds-number flow fields. In addition, the active regions of

$w^\prime$ also in higher-Reynolds-number flow fields. In addition, the active regions of ![]() $w^\prime$ (black dashed line region) are formed in the areas where the large-scale structures of

$w^\prime$ (black dashed line region) are formed in the areas where the large-scale structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ exist. Therefore, we infer that the high-Reynolds-number LES demonstrates the same physical mechanism of drag reduction as observed in the lower-Reynolds-number DNS. These structures are clearly observed in higher-Reynolds-number flow fields even though the small computational domain, i.e.

$u^\prime$ exist. Therefore, we infer that the high-Reynolds-number LES demonstrates the same physical mechanism of drag reduction as observed in the lower-Reynolds-number DNS. These structures are clearly observed in higher-Reynolds-number flow fields even though the small computational domain, i.e. ![]() $L_1 \times L_2 \times L_3 = {\rm \pi}\times 2 \times 0.5{\rm \pi}$, is applied. This is because the length of the computational domain normalized by friction velocity and kinematic viscosity increases as the friction Reynolds number increases. On the basis of the analysis of the instantaneous fields at low to high Reynolds numbers,

$L_1 \times L_2 \times L_3 = {\rm \pi}\times 2 \times 0.5{\rm \pi}$, is applied. This is because the length of the computational domain normalized by friction velocity and kinematic viscosity increases as the friction Reynolds number increases. On the basis of the analysis of the instantaneous fields at low to high Reynolds numbers, ![]() $Re_\tau = 360\unicode{x2013}3240$, it is implied that these key structures of

$Re_\tau = 360\unicode{x2013}3240$, it is implied that these key structures of ![]() $u^\prime$ and

$u^\prime$ and ![]() $w^\prime$ are universal in the drag-reducing flow controlled using the travelling wave-like wall deformation independent of the friction Reynolds number. In summary, the results of the turbulence statistics (figure 10) and the instantaneous flow fields (figure 11) well support the drag reduction mechanism at higher Reynolds numbers, which is basically the same as that at lower Reynolds numbers.

$w^\prime$ are universal in the drag-reducing flow controlled using the travelling wave-like wall deformation independent of the friction Reynolds number. In summary, the results of the turbulence statistics (figure 10) and the instantaneous flow fields (figure 11) well support the drag reduction mechanism at higher Reynolds numbers, which is basically the same as that at lower Reynolds numbers.

Figure 12 shows the mean velocity profiles and RSS in the controlled cases at ![]() $Re_\tau = 360\unicode{x2013}3240$, together with the mean velocity profile at

$Re_\tau = 360\unicode{x2013}3240$, together with the mean velocity profile at ![]() $Re_\tau = 3240$ modelled by the semi-empirical formula (Nabae et al. Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020) in figure 12(

$Re_\tau = 3240$ modelled by the semi-empirical formula (Nabae et al. Reference Nabae, Kawai and Fukagata2020) in figure 12(![]() $a$), i.e.

$a$), i.e.

where ![]() $\alpha$ is the weighting coefficient,

$\alpha$ is the weighting coefficient, ![]() $\gamma ( \xi _2^+ ) = 1 - \exp ( -\xi _2^+ / 25 )$ is the weighting function and

$\gamma ( \xi _2^+ ) = 1 - \exp ( -\xi _2^+ / 25 )$ is the weighting function and ![]() $\nu _t$ in (4.2) is the turbulent viscosity based on the paper by Reynolds & Tiederman (Reference Reynolds and Tiederman1967);

$\nu _t$ in (4.2) is the turbulent viscosity based on the paper by Reynolds & Tiederman (Reference Reynolds and Tiederman1967); ![]() $E ( \xi _2^+ )$ and

$E ( \xi _2^+ )$ and ![]() $U_c$ are utilized for the law of the wake by Krug, Philip & Marusic (Reference Krug, Philip and Marusic2017). As shown in figure 12(

$U_c$ are utilized for the law of the wake by Krug, Philip & Marusic (Reference Krug, Philip and Marusic2017). As shown in figure 12(![]() $a$), the mean velocity profiles in the controlled cases are found to be in reasonable agreement with those obtained using this model. A noteworthy observation is that the slope of the profiles in the logarithmic region decreases as the friction Reynolds number increases; thus, the difference between the mean velocity profile obtained by the present LES and that modelled by the semi-empirical formula of (4.1) is small at