1. Introduction

Rayleigh–Taylor (Rayleigh Reference Rayleigh1882; Taylor Reference Taylor1950), Richtmyer–Meshkov (Richtmyer Reference Richtmyer1960; Meshkov Reference Meshkov1969) and Kelvin–Helmholtz (KH) (Helmholtz Reference Helmholtz1868; Kelvin Reference Kelvin1871) instabilities are crucial in a wide range of natural phenomena and engineering applications, such as supernova explosion (Burrows Reference Burrows2000), inertial confinement fusion (Thomas & Kares Reference Thomas and Kares2012) and so on. In practical flows, these instabilities frequently interact with each other and cause mixing between different materials, and accurate prediction of mixing is of great significance for understanding natural phenomena and optimizing engineering applications. Three primary methodologies are utilized to numerically predict the evolution of mixing: direct numerical simulation (DNS), large eddy simulation (LES), and Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) simulation. Specifically, RANS is widely applied in engineering owing to its high computational efficiency. Its accuracy, however, can be limited, considering that the form and amplitude of the initial perturbations might vary significantly in different scenarios. In the present study, we develop a novel RANS model for mixing problems caused by interfacial instabilities, aiming at a efficient numerical tool that is able to predict different types and stages of mixing flows in a universal framework.

1.1. Three stages of mixing evolution

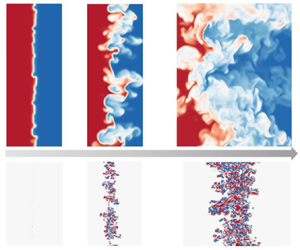

Unsteady mixing evolution typically progresses through three distinct stages: instability development, mixing transition and turbulent mixing. Taking the Rayleigh–Taylor (RT) mixing evolution as an example, for each stage figure 1 displays the corresponding density (upper) and vorticity (lower) fields, to reflect the characteristics of different stages.

Figure 1. Diagram of the three stages of RT mixing evolution. For each stage, the upper and lower images give the corresponding density and vorticity fields, respectively.

In the first stage, the amplitude of the perturbation remains small, featuring a negligible vorticity amplitude and a narrow mixing region. Thus the instability development during this stage is characterized as linear or weakly nonlinear, and analytical theoretical models have been proposed accordingly for single-mode perturbations (Layzer Reference Layzer1955; Mikaelian Reference Mikaelian1998; Goncharov Reference Goncharov2002; Liu, Zhang & Xiao Reference Liu, Zhang and Xiao2022; Zhang & Guo Reference Zhang and Guo2022; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Wu-Wang, Zhang and Xiao2023). Furthermore, for multi-mode cases, these analytical models are also applicable to depict the interfacial evolution, as the perturbed modes grow mostly independently (Rollin & Andrews Reference Rollin and Andrews2013; Canfield et al. Reference Canfield, Denissen, Francois, Gore, Rauenzahn, Reisner and Shkoller2020). In this stage, the linearly growing perturbations dominate the evolution, until the amplitude of the interfacial perturbation becomes comparable to the dominant wavelength.

As the flow progresses to the stage of mixing transition, the interfacial structures start to break into smaller scales, and multiscale behaviour appears due to the coupling and competition between different modes (Zhang & Ni Reference Zhang and Ni2023). Accordingly, the width of the mixing region and the perturbation amplitudes rapidly increase, leading to a pronounced shear effect and a significant increase in vorticity. Notably, for this stage, as shown in figure 1, the vorticity distribution exhibits remarkable inhomogeneity. High- and zero-vorticity regions distribute intermittently near the edges of the mixing region, as marked by the black box. In Richtmyer–Meshkov (RM) flows, where mixing rapidly develops under the impact of shock waves, the inhomogeneous vorticity distribution persists due to the influence of various complex waves, also suggesting the significance of the intermittency. Therefore, the mixing transition stage is characterized by strong nonlinearity, remarkable intermittency and local spatio-temporal dependency, which are intractable for existing analytical models. Attempting to track the development of multiple modes, the modal model has been proposed by Rollin & Andrews (Reference Rollin and Andrews2013) and Canfield et al. (Reference Canfield, Denissen, Francois, Gore, Rauenzahn, Reisner and Shkoller2020), combining Haan's mode coupling equations (Haan Reference Haan1991) and Goncharov's interface evolution model (Goncharov Reference Goncharov2002). Nevertheless, this method's applicability to the strongly nonlinear dynamics in the late mixing transition remains questionable, especially for multi-mode cases with complex mode interactions. Therefore, there is a pressing need to develop applicable methodologies for predicting the mixing transition.

Subsequently, the flow evolves into the turbulent mixing stage, corresponding to the well-mixed state of Dimotakis (Reference Dimotakis2000). In this stage, intense turbulent fluctuations further enhance the shear effect, resulting in a larger amplitude and distribution area of vorticity. Mixing at this stage displays self-similarity and deterministic statistical laws, making it suitable for RANS modelling (Dimonte & Tipton Reference Dimonte and Tipton2006; Kokkinakis et al. Reference Kokkinakis, Drikakis, Youngs and Williams2015; Kokkinakis, Drikakis & Youngs Reference Kokkinakis, Drikakis and Youngs2019; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, He, Xie, Xiao and Tian2020; Xiao, Zhang & Tian Reference Xiao, Zhang and Tian2021; Xie, Zhao & Zhang Reference Xie, Zhao and Zhang2023).

It should be noted that the aforementioned three stages are not always discernible in practical applications. For RT flows, when the amplitudes of initial perturbations or the imposed acceleration are significant, mixing occurs rapidly, rendering the linear and transition stages negligible. Similarly, for RM flows, if the perturbation amplitudes or the incident shock wave Mach number are large, the first two stages can be difficult to observe. However, in many scenarios, the transition effect from a laminar to turbulent state is remarkable, and failing to capture the transition onset can cause significant deviations for numerical predictions. For instance, for the reshocked RM mixing flow where shock waves repeatedly impact the mixing region, Haines, Grinstein & Schwarzkopf (Reference Haines, Grinstein and Schwarzkopf2013) implemented a RANS experiment, where the turbulence model was switched on at different moments to model the effect of transition onset. Based on their observation, it is required to manually switch on the turbulence model at the reshocked moment, so that the RANS calculation can provide satisfactory results compared with implicit LES (ILES). This suggests that a model which is able to automatically detect the transition onset is desired for RANS prediction of mixing transition flows.

1.2. Challenges for RANS prediction of mixing transition flows

Although methodologies have been suggested for the stages of instability development and turbulent mixing, the intermediate mixing transition stage remains a formidable challenge for modelling endeavours due to the profoundly nonlinear behaviours of the perturbed modes. Existing RANS mixing models cannot be directly applied to the mixing transition stage due to their inherent limitation. Specifically, these models are grounded in the assumption of a homogeneous and fully developed turbulent mixing, which does not align with the characteristics of the transition stage. As evidenced by the high-fidelity (HiFi) numerical simulation analysis conducted by Livescu et al. (Reference Livescu, Ristorcelli, Gore, Dean, Cabot and Cook2009) and Morgan & Greenough (Reference Morgan and Greenough2015), the commonly used eddy viscosity closure and gradient diffusion approximation (GDA) within these existing RANS mixing models fall short in accurately describing the mixing transition. Furthermore, the distribution of the vorticity field depicted in figure 1 reveals a substantial intermittency during the transition stage, which has not been reflected by existing RANS models.

Despite the inherent difficulties for transition modelling, efforts have been made to improve the accuracy of RANS predictions for specific mixing transition flows. Firstly, artificially switching on the turbulence model when transition occurs is considered as one possible way to improve RANS results for mixing transition (Haines et al. Reference Haines, Grinstein and Schwarzkopf2013). However, this method deeply depends on the transition criteria. Various methods have been proposed to identify the transition onset. With observations for a series of steady flows, Dimotakis (Reference Dimotakis2000) proposed a transition threshold based on the outer-scale Reynolds number approximately at ![]() $Re=1\sim 2\times 10^4$, which is derived from the emergence of an inertial range signifying the occurrence of transition. Zhou, Robey & Buckingham (Reference Zhou, Robey and Buckingham2003) extended Dimotakis's criterion to the unsteady mixing problem by introducing an additional temporal-associated length scale. Subsequently, Zhou (Reference Zhou2007) further extended the transient criterion of mixing transition and proposed a minimum turbulent state with

$Re=1\sim 2\times 10^4$, which is derived from the emergence of an inertial range signifying the occurrence of transition. Zhou, Robey & Buckingham (Reference Zhou, Robey and Buckingham2003) extended Dimotakis's criterion to the unsteady mixing problem by introducing an additional temporal-associated length scale. Subsequently, Zhou (Reference Zhou2007) further extended the transient criterion of mixing transition and proposed a minimum turbulent state with ![]() $Re=1.6\times 10^5$, ensuring a sufficiently extended inertial range. It is noteworthy that the identification of the inertial range in these criteria can only be obtained based on a posteriori analysis of the energy spectrum, which cannot be used for real-time predictions. Recently, Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Song, Ma, Ma, Wang and Wang2022) proposed a transition criterion based on the mixing mass, enabling the identification of both the onset and cessation of transition. Nevertheless, global quantities like the mixing mass and the outer-scale Reynolds number fail to capture the local characteristics of transition, which are not compatible for practical RANS predictions.

$Re=1.6\times 10^5$, ensuring a sufficiently extended inertial range. It is noteworthy that the identification of the inertial range in these criteria can only be obtained based on a posteriori analysis of the energy spectrum, which cannot be used for real-time predictions. Recently, Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Song, Ma, Ma, Wang and Wang2022) proposed a transition criterion based on the mixing mass, enabling the identification of both the onset and cessation of transition. Nevertheless, global quantities like the mixing mass and the outer-scale Reynolds number fail to capture the local characteristics of transition, which are not compatible for practical RANS predictions.

Secondly, introducing other methods like the modal models or LES is helpful for describing the early-stage interfacial evolution, which can then provide information for initialization of RANS models, thereby achieving predictions for mixing transition. For example, for reshocked RM mixing, Kokkinakis, Drikakis & Youngs (Reference Kokkinakis, Drikakis and Youngs2020) implemented a ILES to depict the interfacial evolution prior to the shock passing, and the ILES results were used to give the initial turbulent kinetic energy for the turbulence model. Rollin & Andrews (Reference Rollin and Andrews2013) adopted the modal model to track the evolution of the perturbed modes, and subsequently applied the modal model's results to initialize the spatial profiles of the physical variables in RANS calculations. Moreover, Braun & Gore (Reference Braun and Gore2020) constructed a zero-dimensional passive model to provide initial conditions for a RANS model. In these combined schemes, however, there exists a common issue that the switching moment between RANS and the other method (the modal model or LES) needs to be clearly specified a priori.

To summarize, a feasible engineering prediction scheme for mixing transition flows is demanded, particularly in the context of RANS modelling studies. The objective of the present study is to develop a novel RANS mixing transition model, which is expected to have the following features. Firstly, it should be based on a uniform RANS framework for easy usage, and does not rely on other methods. Secondly, it should be able to autonomously predict the onset of transition and to accurately describe the spatio-temporal evolution of the transition process. Thirdly, it should be robust for different stages of various types of mixing flows, including typical RT/RM transition flows, and turbulent mixing flows that rapidly develop into a fully turbulent state with a negligible transition process. In order to address these, the key contribution of the proposed model is to accurately incorporate an intermittency model in RANS calculations of mixing transition flows. Inspired by boundary layer transition models (Menter et al. Reference Menter, Langtry, Likki, Suzen, Huang and Völker2006; Wang & Fu Reference Wang and Fu2011; Li, Ju & Zhang Reference Li, Ju and Zhang2023; Rosafio et al. Reference Rosafio, Lopes, Salvadori, Lavagnoli, Be and Misul2023), we introduce the intermittent factor ![]() $\gamma$ and its transport equation, with

$\gamma$ and its transport equation, with ![]() $\gamma =0$ corresponding to a laminar state,

$\gamma =0$ corresponding to a laminar state, ![]() $\gamma =1$ indicating a turbulent state and the intermediate values reflecting the transitional state. The present model will be extensively validated, showing its robustness in different cases.

$\gamma =1$ indicating a turbulent state and the intermediate values reflecting the transitional state. The present model will be extensively validated, showing its robustness in different cases.

The paper is organized as follows. We provide a comprehensive documentation of the modelling process in § 2. Specifically, § 2.1 outlines the governing equations and the baseline model, while § 2.2 details the key modelling idea about the intermittent factor ![]() $\gamma$. Section 2.3 presents the validation of our strategy of introducing

$\gamma$. Section 2.3 presents the validation of our strategy of introducing ![]() $\gamma$ to RANS calculations, and § 2.4 discusses the construction of the transport equation for

$\gamma$ to RANS calculations, and § 2.4 discusses the construction of the transport equation for ![]() $\gamma$. In § 3, we conduct systematic validations and tests for the proposed model. This section includes the validation of the

$\gamma$. In § 3, we conduct systematic validations and tests for the proposed model. This section includes the validation of the ![]() $\gamma$ transport equation in § 3.1, sensitivity tests on model parameters in § 3.2 and an assessment of the accuracy and generalization performance of the present model in § 3.3. Finally, the key contributions of this study are summarized in § 4.

$\gamma$ transport equation in § 3.1, sensitivity tests on model parameters in § 3.2 and an assessment of the accuracy and generalization performance of the present model in § 3.3. Finally, the key contributions of this study are summarized in § 4.

2. Methodology

2.1. Governing equations and baseline model

For interfacial mixing problems, the multicomponent RANS equations are solved by considering molecular transport and thermodynamic coefficients. The transport equations for the mean density ![]() $\rho$, velocity

$\rho$, velocity ![]() $u_{i}$, total energy

$u_{i}$, total energy ![]() $E$ of the mixture and mass fraction

$E$ of the mixture and mass fraction ![]() $Y_{\alpha }$ of species

$Y_{\alpha }$ of species ![]() $\alpha$ are given as follows:

$\alpha$ are given as follows:

$$\begin{gather}\frac{\partial \bar{\rho }{{{\tilde{Y}_{\alpha}}}}}{\partial t}+\frac{\partial \bar{\rho }{{{\tilde{Y}_{\alpha}}}}{{{\tilde{u}}}_{j}}}{\partial {{x}_{j}}}=D_{Y}+\frac{\partial }{\partial {{x}_{j}}}\left(\bar{\rho}\bar{D}\frac{\partial\tilde{Y}_{\alpha}}{\partial x_{j}}\right). \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather}\frac{\partial \bar{\rho }{{{\tilde{Y}_{\alpha}}}}}{\partial t}+\frac{\partial \bar{\rho }{{{\tilde{Y}_{\alpha}}}}{{{\tilde{u}}}_{j}}}{\partial {{x}_{j}}}=D_{Y}+\frac{\partial }{\partial {{x}_{j}}}\left(\bar{\rho}\bar{D}\frac{\partial\tilde{Y}_{\alpha}}{\partial x_{j}}\right). \end{gather}$$

The overbar and tilde represent the Reynolds- and Favre-averaged fields, respectively. Moreover, subscripts ![]() $i,j=1,2,3$ denote the three spatial directions (

$i,j=1,2,3$ denote the three spatial directions (![]() $x,y,z$), and

$x,y,z$), and ![]() $t$ denotes time. Furthermore, the heat flux

$t$ denotes time. Furthermore, the heat flux ![]() $\bar {q}_{c}$, the interspecies diffusional heat flux

$\bar {q}_{c}$, the interspecies diffusional heat flux ![]() $\bar {q}_{d}$, and the viscous stress tensor

$\bar {q}_{d}$, and the viscous stress tensor ![]() $\bar {\sigma }_{ij}$ are given as

$\bar {\sigma }_{ij}$ are given as

Here, ![]() $\bar {\mu }$,

$\bar {\mu }$, ![]() $\bar {D}$,

$\bar {D}$, ![]() $\bar {\kappa }$,

$\bar {\kappa }$, ![]() $C_{p,\alpha }$ and

$C_{p,\alpha }$ and ![]() $g_{i}$ represent dynamic viscosity, mass diffusivity, thermal conductivity, constant-pressure specific heat of species

$g_{i}$ represent dynamic viscosity, mass diffusivity, thermal conductivity, constant-pressure specific heat of species ![]() $\alpha$ and gravitational acceleration in the

$\alpha$ and gravitational acceleration in the ![]() $i$ direction, respectively. In addition, the equation of state (EOS)

$i$ direction, respectively. In addition, the equation of state (EOS) ![]() $\bar {p}M=\bar {\rho }R\tilde {T}$ for the perfect gas is used, with

$\bar {p}M=\bar {\rho }R\tilde {T}$ for the perfect gas is used, with ![]() $M$ and

$M$ and ![]() $R$ denoting the molar mass and the gas constant, respectively. Note that the EOS for the mixture is calculated under the assumptions of iso-temperature (i.e.

$R$ denoting the molar mass and the gas constant, respectively. Note that the EOS for the mixture is calculated under the assumptions of iso-temperature (i.e. ![]() $T_1=T_2=\cdots =T_{\alpha }$) and partial pressure (i.e.

$T_1=T_2=\cdots =T_{\alpha }$) and partial pressure (i.e. ![]() $p=\sum {p}_{\alpha }$) and the fluid properties of the mixture are determined using a species-linearly weighted assumption (Livescu Reference Livescu2013).

$p=\sum {p}_{\alpha }$) and the fluid properties of the mixture are determined using a species-linearly weighted assumption (Livescu Reference Livescu2013).

Equations (2.1)–(2.4) are deduced based on the concept of ensemble averaging, which results in the unclosed terms including the Reynolds stress ![]() $\tau _{ij}$, the turbulent diffusion of the total energy

$\tau _{ij}$, the turbulent diffusion of the total energy ![]() $D_{E}=-\partial (\bar {\rho }\widetilde {{u}_{j}''e''}+\overline {pu_{j}''})/\partial x_{j}$, the turbulent diffusion of the turbulent kinetic energy (TKE,

$D_{E}=-\partial (\bar {\rho }\widetilde {{u}_{j}''e''}+\overline {pu_{j}''})/\partial x_{j}$, the turbulent diffusion of the turbulent kinetic energy (TKE, ![]() $\tilde {K}$)

$\tilde {K}$) ![]() $D_{K}=-\partial (\bar {\rho }\widetilde {{u}_{i}''{u}_{i}''{u}_{j}''}/2)/\partial x_{j}$ and the turbulent diffusion of the mass fraction

$D_{K}=-\partial (\bar {\rho }\widetilde {{u}_{i}''{u}_{i}''{u}_{j}''}/2)/\partial x_{j}$ and the turbulent diffusion of the mass fraction ![]() $D_{Y}=-\partial (\bar {\rho }\widetilde {u_{j}''{Y_{\alpha }}''})/\partial x_{j}$, respectively, the double prime here denoting Favre fluctuation. In previous studies, numerous turbulent mixing models have been proposed to model these unclosed terms, which mostly focus on fully developed turbulence. Taking the well-developed K-L model as an example, the turbulent transport terms are modelled by the GDA

$D_{Y}=-\partial (\bar {\rho }\widetilde {u_{j}''{Y_{\alpha }}''})/\partial x_{j}$, respectively, the double prime here denoting Favre fluctuation. In previous studies, numerous turbulent mixing models have been proposed to model these unclosed terms, which mostly focus on fully developed turbulence. Taking the well-developed K-L model as an example, the turbulent transport terms are modelled by the GDA

where ![]() $f$ denotes an arbitrary physical variable and

$f$ denotes an arbitrary physical variable and ![]() $N_{f}$ is the corresponding model coefficient. Thus, the turbulent diffusion terms are respectively modelled as

$N_{f}$ is the corresponding model coefficient. Thus, the turbulent diffusion terms are respectively modelled as

$$\begin{gather} {D}_{E}=\frac{\partial}{\partial x_{j}}\left(\frac{\mu_{t}}{N_{h}}\frac{\partial \tilde{h}}{\partial x_{j}}\right ), \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather} {D}_{E}=\frac{\partial}{\partial x_{j}}\left(\frac{\mu_{t}}{N_{h}}\frac{\partial \tilde{h}}{\partial x_{j}}\right ), \end{gather}$$ $$\begin{gather}{D}_{K}=\frac{\partial}{\partial x_{j}}\left(\frac{\mu_{t}}{N_{K}}\frac{\partial \tilde{K}}{\partial x_{j}}\right ), \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather}{D}_{K}=\frac{\partial}{\partial x_{j}}\left(\frac{\mu_{t}}{N_{K}}\frac{\partial \tilde{K}}{\partial x_{j}}\right ), \end{gather}$$ $$\begin{gather}{D}_{Y}= \frac{\partial}{\partial x_{j}}\left(\frac{\mu_{t}}{N_{Y}}\frac{\partial \tilde{Y}}{\partial x_{j}}\right), \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather}{D}_{Y}= \frac{\partial}{\partial x_{j}}\left(\frac{\mu_{t}}{N_{Y}}\frac{\partial \tilde{Y}}{\partial x_{j}}\right), \end{gather}$$

where ![]() $h$ represents enthalpy. Importantly, the turbulent viscosity

$h$ represents enthalpy. Importantly, the turbulent viscosity ![]() $\mu _{t}$ is described by the TKE

$\mu _{t}$ is described by the TKE ![]() $\tilde {K}$ and the turbulent length scale

$\tilde {K}$ and the turbulent length scale ![]() $\tilde {L}$

$\tilde {L}$

where ![]() $C_{\mu }$ is a model coefficient. With the classical Boussinesq eddy viscosity hypothesis, the Reynolds stress is modelled as

$C_{\mu }$ is a model coefficient. With the classical Boussinesq eddy viscosity hypothesis, the Reynolds stress is modelled as

where ![]() $C_{P}$ is a model coefficient.

$C_{P}$ is a model coefficient.

Additionally, the transport equations of the TKE and ![]() $\tilde {L}$ are

$\tilde {L}$ are

$$\begin{gather} \frac{\partial \bar{\rho }\tilde{K}}{\partial t}+\frac{\partial \bar{\rho }{{{\tilde{u}}}_{j}}\tilde{K}}{\partial {{x}_{j}}}={-}{{{\tau }}_{ij}}\frac{\partial {{{\tilde{u}}}_{i}}}{\partial {{x}_{j}}}+\frac{\partial }{\partial {{x}_{j}}}\left(\frac{{{\mu }_{t}}}{{{N}_{K}}}\frac{\partial \tilde{K}}{\partial {{x}_{j}}}\right)+{{S}_{Kf}}-D_{r}, \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather} \frac{\partial \bar{\rho }\tilde{K}}{\partial t}+\frac{\partial \bar{\rho }{{{\tilde{u}}}_{j}}\tilde{K}}{\partial {{x}_{j}}}={-}{{{\tau }}_{ij}}\frac{\partial {{{\tilde{u}}}_{i}}}{\partial {{x}_{j}}}+\frac{\partial }{\partial {{x}_{j}}}\left(\frac{{{\mu }_{t}}}{{{N}_{K}}}\frac{\partial \tilde{K}}{\partial {{x}_{j}}}\right)+{{S}_{Kf}}-D_{r}, \end{gather}$$ $$\begin{gather}\frac{\partial \bar{\rho }\tilde{L}}{\partial t}+\frac{\partial \bar{\rho }{{{\tilde{u}}}_{j}}\tilde{L}}{\partial {{x}_{j}}}=\frac{\partial }{\partial {{x}_{j}}}\left(\frac{{{\mu }_{t}}}{{{N}_{L}}}\frac{\partial \tilde{L}}{\partial {{x}_{j}}}\right)+{{C}_{L}}\bar{\rho }\sqrt{2\tilde{K}}+{{C}_{C}}\bar{\rho }\tilde{L}\frac{\partial {{{\tilde{u}}}_{j}}}{\partial {{x}_{j}}}. \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather}\frac{\partial \bar{\rho }\tilde{L}}{\partial t}+\frac{\partial \bar{\rho }{{{\tilde{u}}}_{j}}\tilde{L}}{\partial {{x}_{j}}}=\frac{\partial }{\partial {{x}_{j}}}\left(\frac{{{\mu }_{t}}}{{{N}_{L}}}\frac{\partial \tilde{L}}{\partial {{x}_{j}}}\right)+{{C}_{L}}\bar{\rho }\sqrt{2\tilde{K}}+{{C}_{C}}\bar{\rho }\tilde{L}\frac{\partial {{{\tilde{u}}}_{j}}}{\partial {{x}_{j}}}. \end{gather}$$

Here, the right-hand side terms of (2.14) represent the shear production, turbulent diffusion, buoyancy production ![]() ${{S}_{Kf}}$ and drag

${{S}_{Kf}}$ and drag ![]() $D_{r}={{C}_{D}}\bar {\rho }{{( \sqrt {2\tilde {K}})}^{3}}/{\tilde {L}}$, respectively. The right-hand side terms of (2.15) include the turbulent diffusion, production and compression, successively. In particular, the buoyancy production term

$D_{r}={{C}_{D}}\bar {\rho }{{( \sqrt {2\tilde {K}})}^{3}}/{\tilde {L}}$, respectively. The right-hand side terms of (2.15) include the turbulent diffusion, production and compression, successively. In particular, the buoyancy production term ![]() ${{S}_{Kf}}$ is given based on the formation proposed by Kokkinakis et al. (Reference Kokkinakis, Drikakis, Youngs and Williams2015) as

${{S}_{Kf}}$ is given based on the formation proposed by Kokkinakis et al. (Reference Kokkinakis, Drikakis, Youngs and Williams2015) as

More details about the K-L model can be found in Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, He, Xie, Xiao and Tian2020).

The K-L model presented in this section is used as the baseline model hereafter, and the baseline-standard model coefficients following Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, He, Xie, Xiao and Tian2020) are listed in table 1. Developed for fully developed turbulence, the baseline K-L model is not suitable for the mixing transition stage. The next section will introduce the general idea of constructing the mixing transition model based on the baseline model.

Table 1. The baseline-standard model coefficients of the K-L model.

2.2. Introducing the intermittent factor to the mixing transition model

In the transition process, the mixing flow undergoes dramatic variations from laminar to turbulent states, exhibiting significant intermittency and local spatio-temporal dependence. Specifically, turbulent and non-turbulent regions are intermittently distributed in the mixing region shown in figure 1. This intermittent nature of transition has not been considered in existing RANS mixing models, and this might cause unsatisfactory results. Inspired by boundary layer transition modelling in aerospace engineering, we introduce the intermittent factor ![]() $\gamma$ to mixing flows in the present study, in order to capture the intermittent characteristics in RANS mixing transition models.

$\gamma$ to mixing flows in the present study, in order to capture the intermittent characteristics in RANS mixing transition models.

For transitional flows, the concept of the intermittent factor is usually considered as the possibility of the local flow being turbulent or not. The quantification of ![]() $\gamma$, however, can be non-trivial, particularly due to the difficulty of distinguishing turbulent and non-turbulent regions in unsteady mixing flows. Similar to the definition applied in free jets (Gauding et al. Reference Gauding, Bode, Brahami, Varea and Danaila2021), we use the enstrophy

$\gamma$, however, can be non-trivial, particularly due to the difficulty of distinguishing turbulent and non-turbulent regions in unsteady mixing flows. Similar to the definition applied in free jets (Gauding et al. Reference Gauding, Bode, Brahami, Varea and Danaila2021), we use the enstrophy ![]() $\omega ^2$ for the quantification of

$\omega ^2$ for the quantification of ![]() $\gamma$ in the present study. Firstly, an indicator function is specified as

$\gamma$ in the present study. Firstly, an indicator function is specified as

where ![]() $F$ is the Heaviside function. Moreover,

$F$ is the Heaviside function. Moreover, ![]() $\omega ^2_0$ is a threshold value that is widely accepted in free shear flows to define the interface of turbulent and non-turbulent regions (Holzner et al. Reference Holzner, Liberzon, Nikitin, Luthi, Kinzelbach and Tsinober2008; da Silva et al. Reference da Silva, Hunt, Eames and Westerweel2014; Silva, Zecchetto & Da Silva Reference Silva, Zecchetto and Da Silva2018; Watanabe, Da Silva & Nagata Reference Watanabe, Da Silva and Nagata2019), and the value of

$\omega ^2_0$ is a threshold value that is widely accepted in free shear flows to define the interface of turbulent and non-turbulent regions (Holzner et al. Reference Holzner, Liberzon, Nikitin, Luthi, Kinzelbach and Tsinober2008; da Silva et al. Reference da Silva, Hunt, Eames and Westerweel2014; Silva, Zecchetto & Da Silva Reference Silva, Zecchetto and Da Silva2018; Watanabe, Da Silva & Nagata Reference Watanabe, Da Silva and Nagata2019), and the value of ![]() $\omega ^2_0$ can be obtained from the probability density function (PDF) of the enstrophy distribution (see Gauding et al. Reference Gauding, Bode, Brahami, Varea and Danaila2021). Determination of the

$\omega ^2_0$ can be obtained from the probability density function (PDF) of the enstrophy distribution (see Gauding et al. Reference Gauding, Bode, Brahami, Varea and Danaila2021). Determination of the ![]() $\omega ^2_0$ mainly includes 3 steps, which are introduced briefly as follows and the detailed contents will be published elsewhere. Firstly, plot the PDF of enstrophy distribution. Specially, the local enstrophy is normalized by

$\omega ^2_0$ mainly includes 3 steps, which are introduced briefly as follows and the detailed contents will be published elsewhere. Firstly, plot the PDF of enstrophy distribution. Specially, the local enstrophy is normalized by ![]() $\hat {\omega }$,

$\hat {\omega }$,

\begin{equation} \hat{\omega}=\frac{\displaystyle\int\langle \omega^2\rangle^2\, {{\rm d}\kern0.07em x}}{\displaystyle\int\langle\omega^2\rangle\, {\rm d}\kern0.07em x}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \hat{\omega}=\frac{\displaystyle\int\langle \omega^2\rangle^2\, {{\rm d}\kern0.07em x}}{\displaystyle\int\langle\omega^2\rangle\, {\rm d}\kern0.07em x}, \end{equation}

here, ![]() $\langle \rangle$ represents averaging in the homogeneous

$\langle \rangle$ represents averaging in the homogeneous ![]() $y$–

$y$–![]() $z$ plane perpendicular to the mixing development direction

$z$ plane perpendicular to the mixing development direction ![]() $x$. The PDF of the enstrophy distribution exhibits two peaks, one representing the non-turbulent region, and the other representing the turbulent region. Secondly, find a possible enstrophy value to define the interface separating the non-turbulent and turbulent regions. Thirdly, determine the threshold by calculating the structure function for two points in space. By repeating the abovementioned steps at different moments, we can get the corresponding enstrophy threshold, which is different for different moments.

$x$. The PDF of the enstrophy distribution exhibits two peaks, one representing the non-turbulent region, and the other representing the turbulent region. Secondly, find a possible enstrophy value to define the interface separating the non-turbulent and turbulent regions. Thirdly, determine the threshold by calculating the structure function for two points in space. By repeating the abovementioned steps at different moments, we can get the corresponding enstrophy threshold, which is different for different moments.

Thereafter, the intermittent factor ![]() $\gamma (x,t)$ is obtained by

$\gamma (x,t)$ is obtained by

Note that the definition here indicates that ![]() $\gamma$ varies from

$\gamma$ varies from ![]() $0$ to

$0$ to ![]() $1$. Moreover, based on the analysis for the HiFi

$1$. Moreover, based on the analysis for the HiFi ![]() $\gamma$ profiles, it is noted that the spatial profiles of the late-time intermittent factor collapse together, exhibiting a self-similar characteristic.

$\gamma$ profiles, it is noted that the spatial profiles of the late-time intermittent factor collapse together, exhibiting a self-similar characteristic.

With the intermittent factor ![]() $\gamma$, we now reformulate the turbulence models used for RANS calculation of mixing flows. In particular, the turbulent viscosity in the Reynolds stress closure is the key term to be considered here. Given that the widely used baseline closure in (2.12) is designed for fully developed turbulence, violating the real physics of the transition process, the turbulent viscosity closure requires further modification to capture the intermittent nature of the transition process. Therefore, introducing the intermittent factor

$\gamma$, we now reformulate the turbulence models used for RANS calculation of mixing flows. In particular, the turbulent viscosity in the Reynolds stress closure is the key term to be considered here. Given that the widely used baseline closure in (2.12) is designed for fully developed turbulence, violating the real physics of the transition process, the turbulent viscosity closure requires further modification to capture the intermittent nature of the transition process. Therefore, introducing the intermittent factor ![]() $\gamma$, the turbulent viscosity

$\gamma$, the turbulent viscosity ![]() $\mu _{t}$ is replaced with an effective eddy viscosity

$\mu _{t}$ is replaced with an effective eddy viscosity ![]() $\mu _{eff}$, which is written as

$\mu _{eff}$, which is written as

Here, ![]() $\mu _{nt}$ (‘nt’ means non-turbulent) involves a complex influence of different instability modes. For example, in boundary layer transition modelling (Wang & Fu Reference Wang and Fu2011),

$\mu _{nt}$ (‘nt’ means non-turbulent) involves a complex influence of different instability modes. For example, in boundary layer transition modelling (Wang & Fu Reference Wang and Fu2011), ![]() $\mu _{nt}$ involves the information of the first and second modes, cross-flow mode and so on. However, for interfacial mixing flows, the existing studies do not cover this aspect, thus

$\mu _{nt}$ involves the information of the first and second modes, cross-flow mode and so on. However, for interfacial mixing flows, the existing studies do not cover this aspect, thus ![]() $\mu _{nt}$ is left for future study. Consequently,

$\mu _{nt}$ is left for future study. Consequently, ![]() $\tau _{ij}$ can be reformulated as

$\tau _{ij}$ can be reformulated as

Accordingly, in the turbulent diffusion term modelled by the GDA, ![]() $\mu _{t}$ is also replaced by

$\mu _{t}$ is also replaced by ![]() $\mu _{new}$ in the new transition model.

$\mu _{new}$ in the new transition model.

Equation (2.21) indicates that, when ![]() $\gamma$ is very small, the model provides a negligible Reynolds stress, indicating a non-turbulent state. As

$\gamma$ is very small, the model provides a negligible Reynolds stress, indicating a non-turbulent state. As ![]() $\gamma$ gradually increases,

$\gamma$ gradually increases, ![]() $\mu _{new}$ grows and ultimately recovers to the original

$\mu _{new}$ grows and ultimately recovers to the original ![]() $\mu _t$ when

$\mu _t$ when ![]() $\gamma =1$, correspondingly, the closure of the Reynolds stress back to (2.13). Particularly,

$\gamma =1$, correspondingly, the closure of the Reynolds stress back to (2.13). Particularly, ![]() $\gamma$ is expected to quantify the intermittency, providing a reasonable way to model the growth of turbulent fluctuations in the mixing transition stage.

$\gamma$ is expected to quantify the intermittency, providing a reasonable way to model the growth of turbulent fluctuations in the mixing transition stage.

2.3. Validation of introducing intermittent factor to RANS prediction

In order to validate the strategy of introducing ![]() $\gamma$ to RANS modelling, a three-dimensional (3-D) HiFi simulation of RT mixing with the Atwood number

$\gamma$ to RANS modelling, a three-dimensional (3-D) HiFi simulation of RT mixing with the Atwood number ![]() $A_t=(\rho _1-\rho _2)/(\rho _1+\rho _2)=0.5$,

$A_t=(\rho _1-\rho _2)/(\rho _1+\rho _2)=0.5$, ![]() $\rho _1$ and

$\rho _1$ and ![]() $\rho _2$ representing the densities of the heavy and light fluids respectively, has been performed to extract the distributions of the intermittent factor

$\rho _2$ representing the densities of the heavy and light fluids respectively, has been performed to extract the distributions of the intermittent factor ![]() $\gamma$. Subsequently, the

$\gamma$. Subsequently, the ![]() $\gamma _{HiFi}$ extracted from the HiFi simulation is directly incorporated into the new formulation in (2.21) to conduct a RANS calculation. With this numerical experiment, we attempt to answer the following question. Given accurate quantification of

$\gamma _{HiFi}$ extracted from the HiFi simulation is directly incorporated into the new formulation in (2.21) to conduct a RANS calculation. With this numerical experiment, we attempt to answer the following question. Given accurate quantification of ![]() $\gamma$, is the new formulation in (2.21) able to predict the transition process in RANS calculations?

$\gamma$, is the new formulation in (2.21) able to predict the transition process in RANS calculations?

In the 3-D HiFi simulation, the mass fraction ![]() $\tilde {Y}$ is initialized to follow an error function profile in the

$\tilde {Y}$ is initialized to follow an error function profile in the ![]() $x$ direction, i.e.

$x$ direction, i.e.

where ![]() $\xi (y,z)$ represents the random perturbation imposed at the initial interface, and

$\xi (y,z)$ represents the random perturbation imposed at the initial interface, and ![]() $H_0=0.0008$ cm is the pseudo-interface thickness. The profile (2.22) results in an initial diffusive mixing layer lying across 4 grid points with the width of

$H_0=0.0008$ cm is the pseudo-interface thickness. The profile (2.22) results in an initial diffusive mixing layer lying across 4 grid points with the width of ![]() $0.025$ cm, which characterizes the initial perturbation amplitude and is reflected by setting the initial value of the turbulent length scale

$0.025$ cm, which characterizes the initial perturbation amplitude and is reflected by setting the initial value of the turbulent length scale ![]() $\tilde {L}_0$ in RANS calculation, as listed in table 2. More details about the configuration of the HiFi simulation are documented in Appendix A.

$\tilde {L}_0$ in RANS calculation, as listed in table 2. More details about the configuration of the HiFi simulation are documented in Appendix A.

Table 2. List of the calculated cases. The ‘perturbation type’ represents whether the initial perturbations of the experiments and 3-D simulations corresponding to these cases only include short waves or also include long waves.

With the aid of ![]() $\gamma _{HiFi}$, we implement the corresponding 1-D RANS calculation for this 3-D case. The baseline-standard model coefficients listed in table 1 are used here. We focus on the temporal evolution of total mixing width, which is considered as the most important statistical quantity for engineering applications, and is calculated based on the straightforward species-truncated definition, i.e.

$\gamma _{HiFi}$, we implement the corresponding 1-D RANS calculation for this 3-D case. The baseline-standard model coefficients listed in table 1 are used here. We focus on the temporal evolution of total mixing width, which is considered as the most important statistical quantity for engineering applications, and is calculated based on the straightforward species-truncated definition, i.e.

where ![]() $x|_{\psi =0.99}$ and

$x|_{\psi =0.99}$ and ![]() $x|_{\psi =0.01}$ represent the locations of the heavy fluid with Favre-averaged volume fractions of 0.99 and 0.01. Figure 2 indicates that the baseline model consistently overpredicts the evolution of the mixing width, exhibiting a quadratic curve throughout its progression. By contrast, due to the introduction of the intermittent factor

$x|_{\psi =0.01}$ represent the locations of the heavy fluid with Favre-averaged volume fractions of 0.99 and 0.01. Figure 2 indicates that the baseline model consistently overpredicts the evolution of the mixing width, exhibiting a quadratic curve throughout its progression. By contrast, due to the introduction of the intermittent factor ![]() $\gamma _{HiFi}$, the predictive accuracy is significantly improved. In particular, the instability and transition stages of mixing evolution are well described, aligning with HiFi results. This numerical experiment provides a clear evidence that the strategy of introducing

$\gamma _{HiFi}$, the predictive accuracy is significantly improved. In particular, the instability and transition stages of mixing evolution are well described, aligning with HiFi results. This numerical experiment provides a clear evidence that the strategy of introducing ![]() $\gamma$ as in (2.21) is effective for RANS calculations of mixing transition flows.

$\gamma$ as in (2.21) is effective for RANS calculations of mixing transition flows.

Figure 2. Predictions for temporal evolution of the truncated mixing width for the HiFi RT simulation.

2.4. Transport equation of the intermittent factor for mixing flows

In practical RANS calculations, we usually do not have precursor HiFi data for the ![]() $\gamma$ distribution. Therefore, in order to consider the effect of intermittency in RANS, it is necessary to build a model for depicting the spatio-temporal evolution of the intermittent factor. In this section, a transport equation for

$\gamma$ distribution. Therefore, in order to consider the effect of intermittency in RANS, it is necessary to build a model for depicting the spatio-temporal evolution of the intermittent factor. In this section, a transport equation for ![]() $\gamma$ is constructed.

$\gamma$ is constructed.

Following the framework of constructing the boundary layer transition models based on the intermittent factor (Menter, Esch & Kubacki Reference Menter, Esch and Kubacki2002; Wang & Fu Reference Wang and Fu2011), we present the ![]() $\gamma$ transport equation as follows:

$\gamma$ transport equation as follows:

where ![]() $P_{\gamma }$ and

$P_{\gamma }$ and ![]() $\epsilon _{\gamma }$ represent the product and dissipation terms, respectively, and

$\epsilon _{\gamma }$ represent the product and dissipation terms, respectively, and ![]() $N_{\gamma }$ is a model coefficient. As the mixing flow eventually evolves to a fully developed turbulent state, the new formulation (2.21) should ultimately approach the original formation (2.13). Correspondingly,

$N_{\gamma }$ is a model coefficient. As the mixing flow eventually evolves to a fully developed turbulent state, the new formulation (2.21) should ultimately approach the original formation (2.13). Correspondingly, ![]() $\gamma$ should grow to 1 and subsequently fluctuate around 1 due to the fluctuating nature of turbulence. Accordingly, we introduce

$\gamma$ should grow to 1 and subsequently fluctuate around 1 due to the fluctuating nature of turbulence. Accordingly, we introduce ![]() $\epsilon _{\gamma }=\gamma P_{\gamma }$, which ensures that

$\epsilon _{\gamma }=\gamma P_{\gamma }$, which ensures that ![]() $P_{\gamma }-\epsilon _{\gamma }$ provides a positive net increment during transition, and then tends to

$P_{\gamma }-\epsilon _{\gamma }$ provides a positive net increment during transition, and then tends to ![]() $0$ for the fully developed turbulence.

$0$ for the fully developed turbulence.

The production of the intermittent factor ![]() $P_{\gamma }$ is thus the key term to be closed for the transition model, which is expected to feature two functions, i.e. identifying the onset of transition and depicting the evolution of

$P_{\gamma }$ is thus the key term to be closed for the transition model, which is expected to feature two functions, i.e. identifying the onset of transition and depicting the evolution of ![]() $\gamma$ during the transitional process. It is formulated as

$\gamma$ during the transitional process. It is formulated as

where ![]() $F_{onset}$ serves as a transition switch, and

$F_{onset}$ serves as a transition switch, and ![]() $G_{r}$ describes the growth of

$G_{r}$ describes the growth of ![]() $\gamma$.

$\gamma$.

Here, ![]() $F_{onset}$ is expressed as

$F_{onset}$ is expressed as

where ![]() $\nu$ represents the molecular kinematic viscosity of the mixture,

$\nu$ represents the molecular kinematic viscosity of the mixture, ![]() $Re_{t}$ is the local turbulent Reynolds number and

$Re_{t}$ is the local turbulent Reynolds number and ![]() $Re_{tra}$ is a pre-defined key transition threshold value. Based on the formulation proposed here,

$Re_{tra}$ is a pre-defined key transition threshold value. Based on the formulation proposed here, ![]() $F_{onset}$ is expected to have the following features. Firstly,

$F_{onset}$ is expected to have the following features. Firstly, ![]() $Re_{t}$ is calculated using

$Re_{t}$ is calculated using ![]() $\tilde {K}$ and

$\tilde {K}$ and ![]() $\tilde {L}$ obtained from the corresponding transport equations (2.14) and (2.15), which characterize the spatial-temporal distribution of the local turbulent state. It is noted that the distribution of

$\tilde {L}$ obtained from the corresponding transport equations (2.14) and (2.15), which characterize the spatial-temporal distribution of the local turbulent state. It is noted that the distribution of ![]() $Re_{t}$ is obviously affected by the initial conditions for the turbulence models in RANS calculations, so that

$Re_{t}$ is obviously affected by the initial conditions for the turbulence models in RANS calculations, so that ![]() $F_{onset}$ here can reflect the sensitivity of the transition models to initial perturbations. Secondly, the transition model is activated when

$F_{onset}$ here can reflect the sensitivity of the transition models to initial perturbations. Secondly, the transition model is activated when ![]() $Re_{t}>Re_{tra}$, with the threshold value

$Re_{t}>Re_{tra}$, with the threshold value ![]() $Re_{tra}=10$ set based on the DNS data from Livescu, Wei & Brady (Reference Livescu, Wei and Brady2021). Thirdly, with the

$Re_{tra}=10$ set based on the DNS data from Livescu, Wei & Brady (Reference Livescu, Wei and Brady2021). Thirdly, with the ![]() $exp$ function, the local value of

$exp$ function, the local value of ![]() $F_{onset}$ rapidly grows to

$F_{onset}$ rapidly grows to ![]() $1$ once transition occurs.

$1$ once transition occurs.

The function ![]() $G _{r}$ dominates the evolution of the intermittent factor

$G _{r}$ dominates the evolution of the intermittent factor ![]() $\gamma$, and is given as

$\gamma$, and is given as

\begin{align}

G_{r}&=C_{1}\sqrt{\gamma}\left\{ \underbrace{ (1-\gamma)

\left[\bar{\rho}\sqrt{2\tilde{S}_{ij}\tilde{S}_{ij}}+C_{2}\sqrt{\max

\left(0,-\frac{\partial \bar{\rho}}{\partial x_k}

\frac{\partial \bar{p}}{\partial

x_k}\right)}\right]}_{\mathit{mean\ field}}\right.\nonumber\\

&\quad +\left.\underbrace{

\left(\gamma S_{Kf}-{{{\tau }}_{ij}}\frac{\partial

{{{\tilde{u}}}_{i}}}{\partial

{{x}_{j}}}\right)/\tilde{K}}_{\mathit{turbulent\

fluctuating\ field}} \right\},

\end{align}

\begin{align}

G_{r}&=C_{1}\sqrt{\gamma}\left\{ \underbrace{ (1-\gamma)

\left[\bar{\rho}\sqrt{2\tilde{S}_{ij}\tilde{S}_{ij}}+C_{2}\sqrt{\max

\left(0,-\frac{\partial \bar{\rho}}{\partial x_k}

\frac{\partial \bar{p}}{\partial

x_k}\right)}\right]}_{\mathit{mean\ field}}\right.\nonumber\\

&\quad +\left.\underbrace{

\left(\gamma S_{Kf}-{{{\tau }}_{ij}}\frac{\partial

{{{\tilde{u}}}_{i}}}{\partial

{{x}_{j}}}\right)/\tilde{K}}_{\mathit{turbulent\

fluctuating\ field}} \right\},

\end{align}

where ![]() $C_{1}$ and

$C_{1}$ and ![]() $C_{2}$ are model coefficients. The function

$C_{2}$ are model coefficients. The function ![]() $G_r$ superimposes the mean field and the turbulent fluctuating field, both of which consist of buoyancy and shear effects. They synergistically decide the spatio-temporal evolution of the intermittent factor

$G_r$ superimposes the mean field and the turbulent fluctuating field, both of which consist of buoyancy and shear effects. They synergistically decide the spatio-temporal evolution of the intermittent factor ![]() $\gamma$. Specifically, the mean field includes the amplitude of the mean shear strain rate and the baroclinic term that represents the mean buoyancy effect, which is then multiplied by

$\gamma$. Specifically, the mean field includes the amplitude of the mean shear strain rate and the baroclinic term that represents the mean buoyancy effect, which is then multiplied by ![]() $(1-\gamma )$ according to the definition of the intermittency, while the turbulent fluctuating field includes the turbulent shear and buoyancy terms. It is noted that the baroclinic term promotes the development of instability when it is negative; otherwise, it does not contribute to the flow evolution. Therefore, the form

$(1-\gamma )$ according to the definition of the intermittency, while the turbulent fluctuating field includes the turbulent shear and buoyancy terms. It is noted that the baroclinic term promotes the development of instability when it is negative; otherwise, it does not contribute to the flow evolution. Therefore, the form ![]() $\max (0,-({\partial \bar {\rho }}/{\partial x_k}) ({\partial \bar {p}}/{\partial x_k}))$ is used here, and the square root is used to ensure dimensional consistency. For the mean field, the mean buoyancy term is multiplied by

$\max (0,-({\partial \bar {\rho }}/{\partial x_k}) ({\partial \bar {p}}/{\partial x_k}))$ is used here, and the square root is used to ensure dimensional consistency. For the mean field, the mean buoyancy term is multiplied by ![]() $C_2$, which is used to adjust the weight between the mean shear and mean buoyancy effects during the mixing transition process. Note that for the interfacial mixing problems considered here, the KH effect represented by the mean shear dominates the transition, hence

$C_2$, which is used to adjust the weight between the mean shear and mean buoyancy effects during the mixing transition process. Note that for the interfacial mixing problems considered here, the KH effect represented by the mean shear dominates the transition, hence ![]() $C_2$ is set to a small value (

$C_2$ is set to a small value (![]() $C_2=0.015$) to ensure this. Furthermore, since the closure for the turbulent buoyancy production term

$C_2=0.015$) to ensure this. Furthermore, since the closure for the turbulent buoyancy production term ![]() $S_{Kf}$ is designed for the fully developed turbulent state, it is multiplied by

$S_{Kf}$ is designed for the fully developed turbulent state, it is multiplied by ![]() $\gamma$ to ensure a reasonable description for the mixing transition process. Note that the Reynolds stress

$\gamma$ to ensure a reasonable description for the mixing transition process. Note that the Reynolds stress ![]() $\tau _{ij}$ has included the intermittent factor because of the closure (2.21). The variable

$\tau _{ij}$ has included the intermittent factor because of the closure (2.21). The variable ![]() $\tilde {K}$ in the denominator ensures dimensional consistency. In addition, based on the analysis for HiFi simulation of RT mixing transition flow, it is also noted that, once transition occurs,

$\tilde {K}$ in the denominator ensures dimensional consistency. In addition, based on the analysis for HiFi simulation of RT mixing transition flow, it is also noted that, once transition occurs, ![]() $\gamma$ will rapidly increase to 1 with a steep growth rate, which is achieved by introducing the overall coefficient

$\gamma$ will rapidly increase to 1 with a steep growth rate, which is achieved by introducing the overall coefficient ![]() $C_1\sqrt {\gamma }$.

$C_1\sqrt {\gamma }$.

The main mechanism dominating the ![]() $\gamma$ evolution is different at different stages during the mixing evolution process, which is verified in figure 3. Here, we plot the temporal evolution of the ratio between the mean field and the sum of the two fields integrated along the

$\gamma$ evolution is different at different stages during the mixing evolution process, which is verified in figure 3. Here, we plot the temporal evolution of the ratio between the mean field and the sum of the two fields integrated along the ![]() $x$ direction, i.e. the mixing development direction. Figure 3 indicates that the mean flow dominates the early-time evolution and triggers the transition onset. When the fluctuating field gradually becomes prominent, the turbulent flow dominates the

$x$ direction, i.e. the mixing development direction. Figure 3 indicates that the mean flow dominates the early-time evolution and triggers the transition onset. When the fluctuating field gradually becomes prominent, the turbulent flow dominates the ![]() $\gamma$ evolution.

$\gamma$ evolution.

Figure 3. Temporal evolution of the ratio between the mean field and the sum of the two fields integrated along the mixing development direction ![]() $x$.

$x$.

To conclude, each part of the product term ![]() $P_{\gamma }$ has its specific function, and it is expected that, under their synergy, mixing transition flows can be accurately predicted.

$P_{\gamma }$ has its specific function, and it is expected that, under their synergy, mixing transition flows can be accurately predicted.

3. Model validation

3.1. Validation of the transport equation for the intermittent factor

To validate whether the proposed ![]() $\gamma$ transport equation (2.24) can accurately describe the spatio-temporal evolution of the intermittent factor, we perform a RANS calculation for the HiFi case, based on the (2.24).

$\gamma$ transport equation (2.24) can accurately describe the spatio-temporal evolution of the intermittent factor, we perform a RANS calculation for the HiFi case, based on the (2.24).

Here, the used model coefficients are different from the baseline-standard values listed in table 1. The reason is explained as follows. The baseline-standard values are from Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, He, Xie, Xiao and Tian2020), which proposes a methodology to theoretically derive the constraint relations among the model coefficients of the K-L model. By inputting several known variables into those relations, such as ![]() $\alpha _b$ (the bubble growth rate in RT mixing),

$\alpha _b$ (the bubble growth rate in RT mixing), ![]() $\theta _b$ (the power exponent of bubble growth in RM mixing),

$\theta _b$ (the power exponent of bubble growth in RM mixing), ![]() $\alpha _{KH}$ (the growth rate of KH mixing) and so on, the specific model coefficient values can be obtained immediately. Moreover, once we substitute the obtained model coefficients into RANS equations to calculate RT/RM/KH mixing problems, RANS predictions can give the corresponding self-similar growth rate.

$\alpha _{KH}$ (the growth rate of KH mixing) and so on, the specific model coefficient values can be obtained immediately. Moreover, once we substitute the obtained model coefficients into RANS equations to calculate RT/RM/KH mixing problems, RANS predictions can give the corresponding self-similar growth rate.

For RT mixing flows, ![]() $\alpha _b$ is the key parameter to decide the late-time self-similar scaling. However, the value of

$\alpha _b$ is the key parameter to decide the late-time self-similar scaling. However, the value of ![]() $\alpha _b$ is not a universal constant and sensitively depends on the initial perturbations. Reliable numerical simulations (Youngs Reference Youngs2013) indicate that

$\alpha _b$ is not a universal constant and sensitively depends on the initial perturbations. Reliable numerical simulations (Youngs Reference Youngs2013) indicate that ![]() $\alpha _b$ varies in the range of

$\alpha _b$ varies in the range of ![]() $0.025\sim 0.12$ when different initial perturbations are adopted, particularly

$0.025\sim 0.12$ when different initial perturbations are adopted, particularly ![]() $\alpha _b \sim 0.025$ if the initial perturbations have only short waves (Cabot & Cook Reference Cabot and Cook2006; Livescu et al. Reference Livescu, Wei and Brady2021), with

$\alpha _b \sim 0.025$ if the initial perturbations have only short waves (Cabot & Cook Reference Cabot and Cook2006; Livescu et al. Reference Livescu, Wei and Brady2021), with ![]() $\alpha _b$ exhibiting a relatively larger value if the initial perturbations include long waves. In addition,

$\alpha _b$ exhibiting a relatively larger value if the initial perturbations include long waves. In addition, ![]() $\alpha _b$ is approximatively 0.05 for natural perturbations, as the linear electric motor (LEM) experiment.

$\alpha _b$ is approximatively 0.05 for natural perturbations, as the linear electric motor (LEM) experiment.

However, it is fairly well known that the ability of RANS models to characterize initial perturbations is quite limited and they cannot really capture the differences between initial perturbations’ modes. To enable RANS predictions to reproduce those different self-similar growth rates, the methodology proposed in Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, He, Xie, Xiao and Tian2020) implicitly considers the influence of initial perturbations and inserts the self-similar growth rates into the determination process of the model coefficients, so that the obtained model coefficients can reproduce the corresponding self-similar scaling.

In Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, He, Xie, Xiao and Tian2020), the targeted flow is the LEM experiment, thus the model coefficients, i.e. the values listed in table 1, are set to produce ![]() $\alpha _b \sim 0.05$. However, for the present HiFi RT case, the late-time quadratic growth rate

$\alpha _b \sim 0.05$. However, for the present HiFi RT case, the late-time quadratic growth rate ![]() $\alpha _b$ is approximately 0.04 by the formula

$\alpha _b$ is approximately 0.04 by the formula ![]() $\alpha _b=(dh_b/dt)^2/(4A_tgh_b)$,

$\alpha _b=(dh_b/dt)^2/(4A_tgh_b)$, ![]() $h_b$ representing the bubble width. Therefore, for the present case we set the corresponding model coefficients listed in ‘long wave’ of table 3 to reproduce

$h_b$ representing the bubble width. Therefore, for the present case we set the corresponding model coefficients listed in ‘long wave’ of table 3 to reproduce ![]() $\alpha _b\sim 0.04$. Moreover, the baseline model also uses the same coefficients to produce the same late-time growth rate.

$\alpha _b\sim 0.04$. Moreover, the baseline model also uses the same coefficients to produce the same late-time growth rate.

Table 3. The used model coefficients of the present model for all the calculated cases. Here, the ‘short (long) wave’ represents the perturbation type of the cases listed in table 2. The baseline and the present models adopt the same model coefficients.

The initial values of the turbulence model variables are set as follows. The initial ![]() $\tilde {L}_0$ is set to match the initial mixing layer width in the 3-D HiFi simulations, while the initial TKE

$\tilde {L}_0$ is set to match the initial mixing layer width in the 3-D HiFi simulations, while the initial TKE ![]() $\tilde {K}_0$, which does not have a physical determination method, is given a small value to ensure a correct implementation of the RANS simulation (Dimonte & Tipton Reference Dimonte and Tipton2006; Morán-López & Schilling Reference Morán-López and Schilling2013; Denissen et al. Reference Denissen, Rollin, Reisner and Andrews2014; Kokkinakis et al. Reference Kokkinakis, Drikakis and Youngs2019; Xiao, Zhang & Tian Reference Xiao, Zhang and Tian2020; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, He, Xie, Xiao and Tian2020). The initial intermittent factor

$\tilde {K}_0$, which does not have a physical determination method, is given a small value to ensure a correct implementation of the RANS simulation (Dimonte & Tipton Reference Dimonte and Tipton2006; Morán-López & Schilling Reference Morán-López and Schilling2013; Denissen et al. Reference Denissen, Rollin, Reisner and Andrews2014; Kokkinakis et al. Reference Kokkinakis, Drikakis and Youngs2019; Xiao, Zhang & Tian Reference Xiao, Zhang and Tian2020; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, He, Xie, Xiao and Tian2020). The initial intermittent factor ![]() $\gamma _0$ is set to a small value of

$\gamma _0$ is set to a small value of ![]() $1\times 10^{-16}$ near the interface to enable the successful activation of the RANS model, while in other regions

$1\times 10^{-16}$ near the interface to enable the successful activation of the RANS model, while in other regions ![]() $\gamma _0$ is set to 0.

$\gamma _0$ is set to 0.

Figure 4 shows the temporal evolution of the truncated mixing width ![]() $H$. The good agreement between the present model and the HiFi results demonstrates that the introduction of the

$H$. The good agreement between the present model and the HiFi results demonstrates that the introduction of the ![]() $\gamma$ transport equation (2.24) can effectively improve the RANS predictions for this mixing transition. In addition, it is clear that the baseline model and the present transition model give the same growth rate as the flow evolves to turbulence, because they use the same model coefficients to achieve the same late-time self-similar rate. However, due to the fact that the baseline model is constructed under the assumption of fully developed turbulence, it always gives a quadratic evolution, even for the instability and transition stages. In the inset the temporal evolution of the maximum value

$\gamma$ transport equation (2.24) can effectively improve the RANS predictions for this mixing transition. In addition, it is clear that the baseline model and the present transition model give the same growth rate as the flow evolves to turbulence, because they use the same model coefficients to achieve the same late-time self-similar rate. However, due to the fact that the baseline model is constructed under the assumption of fully developed turbulence, it always gives a quadratic evolution, even for the instability and transition stages. In the inset the temporal evolution of the maximum value ![]() $\gamma _{max}$ of the intermittent factor is shown and reasonably agrees with the HiFi results. This suggests that the

$\gamma _{max}$ of the intermittent factor is shown and reasonably agrees with the HiFi results. This suggests that the ![]() $\gamma$ transport equation is able to capture the evolution of the intermittent factor in this case. Specifically,

$\gamma$ transport equation is able to capture the evolution of the intermittent factor in this case. Specifically, ![]() $\gamma _{max}$ remains zero in the initial stage of mixing evolution, implying a poorly mixed and non-turbulent state before approximately

$\gamma _{max}$ remains zero in the initial stage of mixing evolution, implying a poorly mixed and non-turbulent state before approximately ![]() $t=1.3$ s, and then exhibits a remarkable inflection point at

$t=1.3$ s, and then exhibits a remarkable inflection point at ![]() $t=1.3$ s, signifying the onset of transition. Thereafter,

$t=1.3$ s, signifying the onset of transition. Thereafter, ![]() $\gamma _{max}$ rapidly approaches

$\gamma _{max}$ rapidly approaches ![]() $1$. These variations agree well with our expectations to a mixing transition model. Moreover, figure 4 shows that the sudden increases of

$1$. These variations agree well with our expectations to a mixing transition model. Moreover, figure 4 shows that the sudden increases of ![]() $H$ and

$H$ and ![]() $\gamma _{max}$ both occur at approximately

$\gamma _{max}$ both occur at approximately ![]() $t=1.3$ s, suggesting that the

$t=1.3$ s, suggesting that the ![]() $\gamma$ transport equation (2.24) has been closely coupled with the underlying model, successfully triggering the transition onset.

$\gamma$ transport equation (2.24) has been closely coupled with the underlying model, successfully triggering the transition onset.

Figure 4. Prediction for temporal evolutions of the truncated mixing width ![]() $H$, and the maximum value

$H$, and the maximum value ![]() $\gamma _{max}$ of the intermittent factor (inset).

$\gamma _{max}$ of the intermittent factor (inset).

In addition to the temporal evolution, the spatial profiles of the intermittent factor scaled by its maximum value are shown in figure 5. Overall, the ![]() $\gamma$ profiles predicted by the present transition model agree well with the HiFi results. This further indicates that the transport equation (2.24) is constructed reasonably and models the

$\gamma$ profiles predicted by the present transition model agree well with the HiFi results. This further indicates that the transport equation (2.24) is constructed reasonably and models the ![]() $\gamma$ evolution well.

$\gamma$ evolution well.

Figure 5. Spatial profiles of the intermittent factor scaled by its maximum value. (a–d) Correspond to ![]() $t=1.63$ s,

$t=1.63$ s, ![]() $t=2.65$ s,

$t=2.65$ s, ![]() $t=3.63$ s and

$t=3.63$ s and ![]() $t=4.56$ s, respectively.

$t=4.56$ s, respectively.

3.2. Sensitivity tests on model parameters

The present model additionally introduces 4 model coefficients, i.e. ![]() $N_\gamma$ in the diffusion term,

$N_\gamma$ in the diffusion term, ![]() $C_1$ and

$C_1$ and ![]() $C_2$ in the production term (2.27) and the transition threshold

$C_2$ in the production term (2.27) and the transition threshold ![]() $Re_{tra}$ in the transition switch function (2.26). The sensitivity of these coefficients is tested in this part. In addition, the influence of the initial

$Re_{tra}$ in the transition switch function (2.26). The sensitivity of these coefficients is tested in this part. In addition, the influence of the initial ![]() $\tilde {L}_0$ and

$\tilde {L}_0$ and ![]() $\tilde {K}_0$ on the prediction results of the present model is also verified.

$\tilde {K}_0$ on the prediction results of the present model is also verified.

3.2.1. Sensitivity tests on the model coefficients

Firstly, the sensitivity of ![]() $N_\gamma$ is checked. In general, the diffusion coefficient influences the shape of the spatial profile, thus the

$N_\gamma$ is checked. In general, the diffusion coefficient influences the shape of the spatial profile, thus the ![]() $\gamma$ profiles at

$\gamma$ profiles at ![]() $t=7$ s in figure 6(a) with different

$t=7$ s in figure 6(a) with different ![]() $N_\gamma$ are displayed. This indicates that

$N_\gamma$ are displayed. This indicates that ![]() $N_\gamma$ indeed influences the intermittent factor's diffusion behaviour such that a smaller

$N_\gamma$ indeed influences the intermittent factor's diffusion behaviour such that a smaller ![]() $N_\gamma$ leads to a more diffused spatial distribution, which is attributed to the fact that a smaller

$N_\gamma$ leads to a more diffused spatial distribution, which is attributed to the fact that a smaller ![]() $N_\gamma$ results in a larger diffusion term.

$N_\gamma$ results in a larger diffusion term.

Figure 6. (a) Spatial profiles of the scaled intermittent factor with different ![]() $N_\gamma$; (b) temporal evolutions of

$N_\gamma$; (b) temporal evolutions of ![]() $\gamma _{max}$ and the total mixing width with different

$\gamma _{max}$ and the total mixing width with different ![]() $Re_{tra}$; (c) temporal evolutions of

$Re_{tra}$; (c) temporal evolutions of ![]() $\gamma _{max}$ and the total mixing width with different

$\gamma _{max}$ and the total mixing width with different ![]() $C_{1}$; (d) temporal evolutions of

$C_{1}$; (d) temporal evolutions of ![]() $\gamma _{max}$ and the total mixing width with different

$\gamma _{max}$ and the total mixing width with different ![]() $C_2$; (e) temporal evolutions of

$C_2$; (e) temporal evolutions of ![]() $\gamma _{max}$ and the total mixing width with different

$\gamma _{max}$ and the total mixing width with different ![]() $\tilde {K}_0$; ( f) temporal evolutions of

$\tilde {K}_0$; ( f) temporal evolutions of ![]() $\gamma _{max}$ and the total mixing width with different

$\gamma _{max}$ and the total mixing width with different ![]() $\tilde {L}_0$.

$\tilde {L}_0$.

The sensitivity test on ![]() $Re_{tra}$ is shown in figure 6(b), where the temporal evolutions of the maximum values of the intermittent factor and the total mixing width are plotted, indicating that

$Re_{tra}$ is shown in figure 6(b), where the temporal evolutions of the maximum values of the intermittent factor and the total mixing width are plotted, indicating that ![]() $Re_{tra}$ mainly impacts the transition onset, a larger

$Re_{tra}$ mainly impacts the transition onset, a larger ![]() $Re_{tra}$ causing a later transition.

$Re_{tra}$ causing a later transition.

Next, we test the sensitivity of ![]() $C_1$ and

$C_1$ and ![]() $C_2$. Figure 6(c,d) gives the temporal evolutions of the maximum values of the intermittent factor and the total mixing width with different

$C_2$. Figure 6(c,d) gives the temporal evolutions of the maximum values of the intermittent factor and the total mixing width with different ![]() $C_2$ and

$C_2$ and ![]() $C_1$. It indicates that

$C_1$. It indicates that ![]() $C_2$ significantly affects the transition moment, and a larger

$C_2$ significantly affects the transition moment, and a larger ![]() $C_2$ results in an earlier transition. This is attributed to the fact that a larger

$C_2$ results in an earlier transition. This is attributed to the fact that a larger ![]() $C_2$ results in a larger mean buoyancy term, corresponding to a stronger force to trigger the transition. The parameter

$C_2$ results in a larger mean buoyancy term, corresponding to a stronger force to trigger the transition. The parameter ![]() $C_1$ directly changes the amplitude of the production term of the

$C_1$ directly changes the amplitude of the production term of the ![]() $\gamma$ transport equation, thus a larger value results in a larger growth rate of the intermittent factor.

$\gamma$ transport equation, thus a larger value results in a larger growth rate of the intermittent factor.

In the present study, the values of ![]() $N_\gamma$,

$N_\gamma$, ![]() $C_1$ and

$C_1$ and ![]() $C_2$ are calibrated based on the HiFi RT case, while

$C_2$ are calibrated based on the HiFi RT case, while ![]() $Re_{tra}=10$ is determined based on the DNS data of Livescu et al. (Reference Livescu, Wei and Brady2021). These values are consistently used for all the cases in the present study.

$Re_{tra}=10$ is determined based on the DNS data of Livescu et al. (Reference Livescu, Wei and Brady2021). These values are consistently used for all the cases in the present study.

3.2.2. Sensitivity tests on the initial  $\tilde {L}_0$ and

$\tilde {L}_0$ and  $\tilde {K}_0$

$\tilde {K}_0$

For practical applications, achieving an accurate control for the transition onset is crucial, which has been considered in (2.26) of the ![]() $F_{onset}$. Specifically, the influence of the initial conditions

$F_{onset}$. Specifically, the influence of the initial conditions ![]() $\tilde {L}_0$ and

$\tilde {L}_0$ and ![]() $\tilde {K}_0$ on the transition onset are tested by two sets of RANS calculations. The first group maintains a fixed

$\tilde {K}_0$ on the transition onset are tested by two sets of RANS calculations. The first group maintains a fixed ![]() $\tilde {L}_0=0.025$ cm to match the initial mixing layer width in the HiFi simulation while varying

$\tilde {L}_0=0.025$ cm to match the initial mixing layer width in the HiFi simulation while varying ![]() $\tilde {K}_0$ from

$\tilde {K}_0$ from ![]() $2.5\times 10^{-8}$ to

$2.5\times 10^{-8}$ to ![]() $2.5\times 10^{-2}\ {\rm cm}^2\ {\rm s}^{-2}$. The second group keeps a fixed

$2.5\times 10^{-2}\ {\rm cm}^2\ {\rm s}^{-2}$. The second group keeps a fixed ![]() $\tilde {K}_0=2.5\times 10^{-6}\ {\rm cm}^2\ {\rm s}^{-2}$ and changes

$\tilde {K}_0=2.5\times 10^{-6}\ {\rm cm}^2\ {\rm s}^{-2}$ and changes ![]() $\tilde {L}_0$ from 0.01 to 0.05 cm. Figure 6(e, f) gives the temporal evolution of

$\tilde {L}_0$ from 0.01 to 0.05 cm. Figure 6(e, f) gives the temporal evolution of ![]() $\gamma _{max}$ and the mixing width

$\gamma _{max}$ and the mixing width ![]() $H$ for different initial conditions, revealing that both

$H$ for different initial conditions, revealing that both ![]() $\tilde {L}_0$ and

$\tilde {L}_0$ and ![]() $\tilde {K}_0$ indeed affect the onset of transition, and larger initial values lead to an earlier transition (Youngs Reference Youngs2013; Ni, Zeng & Zhang Reference Ni, Zeng and Zhang2023).

$\tilde {K}_0$ indeed affect the onset of transition, and larger initial values lead to an earlier transition (Youngs Reference Youngs2013; Ni, Zeng & Zhang Reference Ni, Zeng and Zhang2023).

However, note that the present model is more sensitive to variation of ![]() $\tilde {L}_0$, as a slight increment can significantly promote the transition. In comparison,

$\tilde {L}_0$, as a slight increment can significantly promote the transition. In comparison, ![]() $\tilde {K}_0$ differs by several orders of magnitude in these tests, while the deviation in figure 6(e) is not significant. Moreover, comparing the sensitivity of

$\tilde {K}_0$ differs by several orders of magnitude in these tests, while the deviation in figure 6(e) is not significant. Moreover, comparing the sensitivity of ![]() $Re_{tra}$ with that of the initial

$Re_{tra}$ with that of the initial ![]() $\tilde {L}_0$ and

$\tilde {L}_0$ and ![]() $\tilde {K}_0$, we can see that influence of the

$\tilde {K}_0$, we can see that influence of the ![]() $Re_{tra}$ is much weaker than

$Re_{tra}$ is much weaker than ![]() $\tilde {L}_0$ and stronger than

$\tilde {L}_0$ and stronger than ![]() $\tilde {K}_0$. This is attributed to the fact that

$\tilde {K}_0$. This is attributed to the fact that ![]() $Re_{tra}$ only affects the model's judgement for the local transition behaviour, while

$Re_{tra}$ only affects the model's judgement for the local transition behaviour, while ![]() $\tilde {L}_0$ is closely related to the initial perturbation amplitude and significantly influences the evolutionary velocity of mixing flows. A larger

$\tilde {L}_0$ is closely related to the initial perturbation amplitude and significantly influences the evolutionary velocity of mixing flows. A larger ![]() $\tilde {L}_{0}$ signifies a more significant initial perturbation, thereby promoting the mixing evolution. The insensitivity of the present model to

$\tilde {L}_{0}$ signifies a more significant initial perturbation, thereby promoting the mixing evolution. The insensitivity of the present model to ![]() $\tilde {K}_{0}$ is advantageous for users, as it mitigates uncertainties introduced by this parameter.

$\tilde {K}_{0}$ is advantageous for users, as it mitigates uncertainties introduced by this parameter.

It is noted that during the stage of ![]() $\gamma =0$ the growth rate of the mixing width is independent of the initial

$\gamma =0$ the growth rate of the mixing width is independent of the initial ![]() $\tilde {K}_{0}$ and

$\tilde {K}_{0}$ and ![]() $\tilde {L}_{0}$, which can be explained from the species equation (2.4), due to the fact that the mixing width is calculated based on the species variable. Here, we plot the budget of the right side of (2.4) at

$\tilde {L}_{0}$, which can be explained from the species equation (2.4), due to the fact that the mixing width is calculated based on the species variable. Here, we plot the budget of the right side of (2.4) at ![]() $t=0.2$ s and

$t=0.2$ s and ![]() $t=0.4$ s, as shown in figure 7. It shows that, during the early-time stage of mixing evolution, the turbulent diffusion term is much less than the molecular diffusion term, indicating that the molecular diffusion term dominates the evolution of the mixing width. Consequently, it is significant to consider the molecular effect for mixing transition flows. Figure 8 further plots the temporal evolution of the kinetic energy during the stage of

$t=0.4$ s, as shown in figure 7. It shows that, during the early-time stage of mixing evolution, the turbulent diffusion term is much less than the molecular diffusion term, indicating that the molecular diffusion term dominates the evolution of the mixing width. Consequently, it is significant to consider the molecular effect for mixing transition flows. Figure 8 further plots the temporal evolution of the kinetic energy during the stage of ![]() $\gamma =0$, and the total TKE and the total mean kinetic energy (MKE) are displayed. They are calculated based on the following formulas:

$\gamma =0$, and the total TKE and the total mean kinetic energy (MKE) are displayed. They are calculated based on the following formulas:

Figure 8 indicates that the TKE still grows even though ![]() $\gamma =0$, which is attributed to the fact that the isotropic part of the Reynolds stress is retained. Growth of the TKE reflects the physics that the laminar flow fields can have significant velocity fluctuations. By contrast, the MKE is quite small and can be ignored in this stage.

$\gamma =0$, which is attributed to the fact that the isotropic part of the Reynolds stress is retained. Growth of the TKE reflects the physics that the laminar flow fields can have significant velocity fluctuations. By contrast, the MKE is quite small and can be ignored in this stage.

Figure 7. Budget of the right side of the species equation (2.4). (a,b) Correspond to the moments of ![]() $t=0.2$ s and

$t=0.2$ s and ![]() $t=0.4$ s, respectively.

$t=0.4$ s, respectively.