Are elected officials more responsive to men than women when they receive requests about government services? Women face discrimination in many realms of politics. Political parties are more responsive to the preferences of men (Homola Reference Homola2019), party leaders are more likely to recruit men (Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2013; Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2010; Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2010), and gender bias in voting still penalizes female candidates, even when outright prejudice is on the decline (Anzia and Berry Reference Anzia and Berry2011; Fulton Reference Fulton2012; Teele, Kalla, and Rosenbluth Reference Teele, Kalla and Rosenbluth2018). Does this discrimination extend to other aspects of politics, such as the interaction between elected officials and female constituents?

Perhaps counterintuitively, some considerations suggest that women may face a positive bias in their interaction with legislators. The reason could be that female representatives are more responsive to women. Indeed, women in office have been especially supportive of the interests and rights of women, often promoting women-related legislation (Bratton Reference Bratton2005; Franceschet and Piscopo Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008; O’Brien and Piscopo Reference O’Brien and Piscopo2019; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2006; Swers Reference Swers2002; Vega and Firestone Reference Vega and Firestone1995). Such a positive disposition may also manifest in greater responsiveness of female elected officials to women.

To shed light on the issue, this article investigates whether politicians discriminate on the basis of gender when they address constituents’ requests. In recent years, a growing number of studies have explored elected officials’ responsiveness to citizens, often adopting audit experiments. The vast majority of audit studies took place in the USA (Costa Reference Costa2017) and focused on racial bias (Butler and Brockman Reference Butler and Broockman2011; Butler and Crabtree Reference Butler and Crabtree2017; Einstein and Glick Reference Einstein and Glick2017; Grose Reference Grose2014; Mendez Reference Mendezn.d.; Mendez and Grose Reference Mendez and Grose2018). Some experiments explored socio-economic discrimination (Carnes and Holbein Reference Carnes and Holbein2019; Habel and Birch Reference Habel and Birch2019).Footnote 1

Work on gender bias is more limited. The few studies available have examined elected officials’ responsiveness to young men and women seeking political mentorship and found no bias (Golder, Crabtree, and Dhima Reference Golder, Crabtree and Dhima2019; Kalla, Rosenbluth, and Teele Reference Kalla, Rosenbluth and Teele2017) or a positive bias toward women (Dhima Reference Dhima2018; Rhinehart Reference Rhinehart2020). Another study assessed how officials’ gender influenced citizens’ engagement with their representatives (Costa and Schaffner Reference Costa and Schaffner2018). Previous work, however, has generally overlooked a core function of elected officials: their responsiveness to citizens seeking access to government services. Exploring how gender affects responsiveness is important to assess whether women and men are equally well-represented.

We investigate gender bias in legislators’ responsiveness with the first large-scale audit experiment conducted in 11 countries across two continents. We carried out the experiment with all sitting members of parliament (MPs) in five countries in Europe (France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, and the Netherlands) and six in Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Uruguay). Our selected countries vary with regard to electoral systems – which may influence legislators’ extrinsic motivations (Broockman Reference Broockman2013; de Vries, Dinas, and Solaz Reference de Vries, Dinas and Solazn.d.) – and the proportion of female MPs – which could shape the link between gender and responsiveness (Desposato and Norrander Reference Desposato and Norrander2009; Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2007).

In the experiment, a citizen alias whose gender is randomized to be either female or male sends an email to MPs inquiring about access to unemployment benefits (in Europe) or healthcare services (in Latin America). Across the two regions, we find that gender has a surprising effect on responsiveness. Legislators are overall significantly more likely to respond to women (+3% points), especially in Europe (+4.3% points). In Europe, this result is driven by the behavior of female legislators, who reply more often to women than men at a substantively meaningful rate (+8.4% points).

Our article offers significant contributions. The great majority of prior audit experiments took place in the USA, and the few non-American studies have usually been single-country experiments. No study has previously included such a large number of countries across two regions of the world. Thus, an important contribution of our article is that, by conducting similar experiments in multiple countries, it expands our knowledge of the effect of constituent gender on elected officials’ responsiveness in a wider variety of cultural, social, economic, and political contexts.

The implications of our findings are also significant. While the observational literature on gender and politics has shown a link between the descriptive and the substantive representation of women, experimental studies on gender bias in legislator responsiveness have generally reported null effects. In contrast, we found that women receive more replies because of the higher responsiveness from female legislators, at least in Europe. Consistently with earlier observational findings, this implies that more women in office would lead to a higher quality of representation for women. Increasing the number of female legislators is therefore crucial at a time when women still constitute less than 50% of members of parliament in all but four countries in the world.Footnote 2

Elected officials and responsiveness to citizens

Providing help to citizens with problems that arise in their daily life, especially during hard times, is an important aspect of representation. In her seminal work, Pitkin defined political representation as “acting in the interest of the represented, in a manner responsive to them” (Reference Pitkin1967, 209). One strategy to study responsiveness is to record whether representatives reply to correspondence from citizens.

Most audit experiments have been conducted in the USA and explored racial bias. They found that black residents receive fewer responses than their white counterparts (Butler and Brockman Reference Butler and Broockman2011; Butler and Crabtree Reference Butler and Crabtree2017; but see Einstein and Glick Reference Einstein and Glick2017). Latinos, too, are less likely than whites to obtain an answer (Mendez and Grose Reference Mendez and Grose2018; White, Nathan, and Faller Reference White, Nathan and Faller2015), especially if they are undocumented (Mendez Reference Mendezn.d.). In contrast, constituents’ social class does not seem to drive discrimination (Carnes and Holbein Reference Carnes and Holbein2019).

The few studies outside the USA have usually been single-country experiments and have shown mixed results. While McClendon (Reference McClendon2016) and Distelhorst and Hou (Reference Distelhorst and Hou2014) reveal that racial and ethnic discrimination are common among local officials in South Africa and China, Grose (Reference Grose2015) find little evidence of such bias in Germany. There is also some evidence on class bias in the UK (Habel and Birch Reference Habel and Birch2019). Two comparative audit studies in Europe highlight the importance of intrinsic motivations and the lack of nationalistic bias in elected officials’ responses (Butler, de Vries, and Solaz Reference Butler, De Vries and Solaz2019; de Vries, Dinas and Solaz Reference de Vries, Dinas and Solazn.d.).

Work on gender bias is limited and generally focused on political mentorship. Two studies found no bias in elected officials’ responses to young men and women seeking political advice in the USA (Kalla, Rosenbluth, and Teele Reference Kalla, Rosenbluth and Teele2017) and New Zealand (Golder, Crabtree, and Dhima Reference Golder, Crabtree and Dhima2019). Two other studies – conducted in Canada and the USA – actually found that elected officials respond more to women than men interested in running for office (Dhima Reference Dhima2018; Rhinehart Reference Rhinehart2020). Another study found no discrimination from bureaucrats toward men and women inquiring about public housing (Einstein and Glick Reference Einstein and Glick2017).

Little is known, however, on whether gender bias exists in elected officials’ responses to constituents seeking access to government services, which is a core function of an elected official. We therefore investigate whether legislators discriminate against women or men when answering requests for government assistance and whether they are more responsive to citizens of their own gender.

On the one hand, women face discrimination in many sectors of politics. Such discrimination may also extend to the interaction between women and elected officials, which may lead to fewer responses to women seeking help. On the other hand, elected officials concerned about re-election may adopt strategic calculations (Canon Reference Canon1999; Grose Reference Grose2011) and reply to constituents regardless of the constituent’s gender. For example, because of extrinsic motivations, white members of Congress in the USA are more likely to respond to welfare requests from black citizens living in their district than to black citizens outside their district (Broockman Reference Broockman2013).

Still another possibility is that women seeking government help actually receive more responses. This could happen if female legislators showed greater responsiveness to women. We know that female legislators exhibit higher responsiveness in general (Thomsen and Sanders Reference Thomsen and Sanders2019). And we also know that minority legislators often care about advancing the interests of their own group, which helps explain the connection between descriptive and substantive representation (Burden Reference Burden2007). With regard to responsiveness, for instance, in the USA black legislators – who are guided by an intrinsic motivation to foster the interests of black citizens – respond at a similar rate to black citizens living inside or outside their district (Broockman Reference Broockman2013).

The greater responsiveness of female legislators to women would be consistent with findings from the observational literature on gender and politics, which has shown a link between descriptive and substantive representation. The election of female legislators has promoted women’s rights, women-friendly policies, and women political participation in the USA (Carroll Reference Carroll2001; Swers Reference Swers2002), Europe (Diaz Reference Diaz2005; Greene and O’Brien Reference Greene and O’Brien2016) and Latin America (Desposato and Norrander Reference Desposato and Norrander2009; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2010). If female legislators are intrinsically motivated to promote women’s interests, they should be especially responsive to women, regardless of electoral considerations.

Experimental design

We developed a comparative audit experiment to test these alternative hypotheses. We conducted experiments with MPs in 11 countries in Europe (France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, and the Netherlands) and Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Mexico, and Uruguay). We collected the list of MPs and their email addresses on the website of each country’s parliament and we wrote to all sitting MPs, for a total of 3,685 emails. A citizen alias contacted MPs via email, sending messages on the central days of the week (Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday).Footnote 3

The email asked for help with access to unemployment benefits (in Europe) and healthcare services (in Latin America). We formulated comparable requests on two issues that are especially relevant in the two regions. In Europe, whereas unemployment benefits remain a concern to many, access to healthcare services is widespread. In contrast, Latin American citizens still face limitations to healthcare access.Footnote 4 The messages were short, written in the language of each country, and composed of simple sentences to increase the requests’ credibility.

Message in European countries:

Dear Mr./Ms. XXX,

My name is FirstName LastName. I lost my job and I don’t know what to do. What should I do to get unemployment benefits? No one will tell me where to go.

Thank you,

FirstName LastName

Message in Latin American countries:

Dear Mr./Ms. XXX,

My name is FirstName LastName. Last year, I was diagnosed with kidney failure, I don’t have insurance and don’t know what to do. How can I access free treatment? I hope you can help me. Thank you very much.

Sincerely,

FirstName LastName

We adopted a randomized block design, in which the treatment consisted of randomly varying the gender of the alias sending the message within each country. To do this, in each country we randomized the sender’s first name, selecting a common name whose gender could be easily identified. We also chose popular last names, which have no regional connotation and are the same for men and women in each country.Footnote 5

We focus on whether MPs reply or not to the emails requesting help, and we recorded replies received within 2 months of the date when the email was sent. The binary dependent variable equals 1 for MPs who replied and 0 for those who did not. Because we are interested in whether MPs provide information to citizens, we assign 1 only to “real replies.” We consider “real replies” messages that contain information addressing the question, while we assign 0 to responses that ask for the sender’s location of residence without offering any help. Therefore, replies that do not provide any information, automatic replies, and lack of replies are all coded as 0 (see McClendon Reference McClendon2016; Butler Reference Butler2014 for a similar approach).Footnote 6

Ethical considerations

There are some ethical concerns that we seriously considered before conducting our study. First, to minimize the burden placed on MPs, we ensured that the costs associated with responding to our messages would be relatively low for MPs. We earnestly followed the advice from the literature (Butler and Broockman Reference Butler and Broockman2011; Broockman Reference Broockman2013; Druckman, Leeper, and Mullnix Reference Druckman, Leeper, Mullinix, Shane, Saalfeld and Strøm2014; Grose Reference Grose2014; McClendon Reference McClendon2012). Our messages were short, concise, and easy for MPs to answer. Most answers to our messages would include a few words of advice and a link to a website or the name of a governmental institution. We found that this was actually the case among the replies we received.

Second, our experiment involved deception regarding the identity of the sender, since our goal was to assess the different behavior of MPs to male versus female constituents. However, our study was not in violation of any laws in our countries of study. Moreover, our study was granted an exemption (category 3: elected officials) by the Office of Human Research Ethics, part of the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.Footnote 7

Third, we were aware of the concern of many scholars about the risk of limiting the pool of legislators through recurrent field experiments on the same sample (Grose Reference Grose2014; Naurin and Öhberg Reference Naurin and Öhberg2019). To our knowledge, our experiment was one of the first of its kind to be conducted with the sample of MPs we used in all our countries in Latin America and in most of our European countries.

Case selection

We include cases from Europe and Latin America. Since electoral systems may affect MPs’ extrinsic motivations to reply, within each region we selected countries with majoritarian (France and Chile), open-list proportional representation (PR) (Ireland, Netherlands, Colombia, and Brazil), and closed-list PR (Italy, Argentina, and Uruguay) systems. Germany and Mexico have a mixed electoral system, electing part of the legislature through majoritarian first-past-the-post and the other via closed-list PR. Further, within each region and for each electoral system, we selected a pair of countries with higher and lower percentages of female legislators in the lower house of parliament. Therefore, we have five European countries and six Latin American countries.

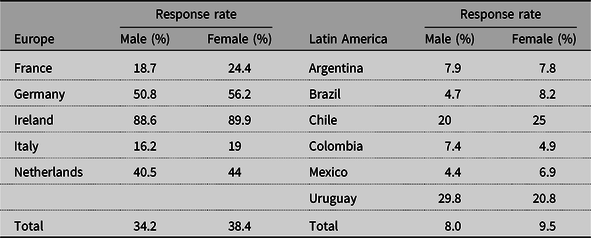

Table 1 reports the general response rate. Variation across countries is large, with the response rate ranging from 5.7% in Mexico to 89.2% in Ireland. The rates are generally higher in Europe, although two Latin American countries – Uruguay and Chile – produced rates greater than the ones observed in France and Italy. Readers should be careful about making comparisons between countries since MPs’ status and expected duties vary across cases. These differences, however, do not interfere with the experimental treatment because both male and female aliases within countries are exposed to the same conditions.

Table 1 Cases and Overall Response Rate

NOTES: France and Chile have majoritarian systems. Netherlands, Colombia, and Brazil use open-list PR; Ireland uses a PR single transferable vote. Italy, Argentina, and Uruguay use closed-list PR. Germany and Mexico have a mixed electoral system. Germany elects 299 MPs through majoritarian first-past-the-post and the remaining (roughly) through a closed-list PR system; Mexico elects 300 MPs through majoritarian first-past-the-post and 200 members through closed-list PR.

Results

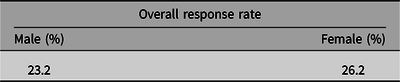

Overall, women receive significantly more replies than men. The general response rate is 26.2% for women and 23.2% for men (p-value = 0.03).Footnote 8 This finding is quite surprising if one considers previous null results in the literature (Butler Reference Butler2014; Kalla, Rosenbluth, and Teele Reference Kalla, Rosenbluth and Teele2017) and the fact that women face discrimination in many aspects of politics.Footnote 9

Evaluating response rates across regions (Table 3), we find that women received more replies in Europe, where the impact of gender is consistent across countries. In Latin America, in contrast, women received more replies only in Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. Overall, the largest differences in response rate to female versus male citizens emerge in France (5.7% points), Germany (5.4% points), and Chile (5% points).

Table 2 Overall MPs Response Rate to Female and Male Citizens

Table 3 MPs Response Rate to Female and Male Citizens across Countries

NOTES: The total number of emails sent within each country was 3,685. France: 561; Germany: 630 (majoritarian: 287; PR: 343); Netherlands: 149; Ireland: 158; Italy: 630; Mexico: 458 (majoritarian: 280; PR: 178); Chile: 120; Colombia: 115; Brazil: 514; Argentina: 255; Uruguay: 95.

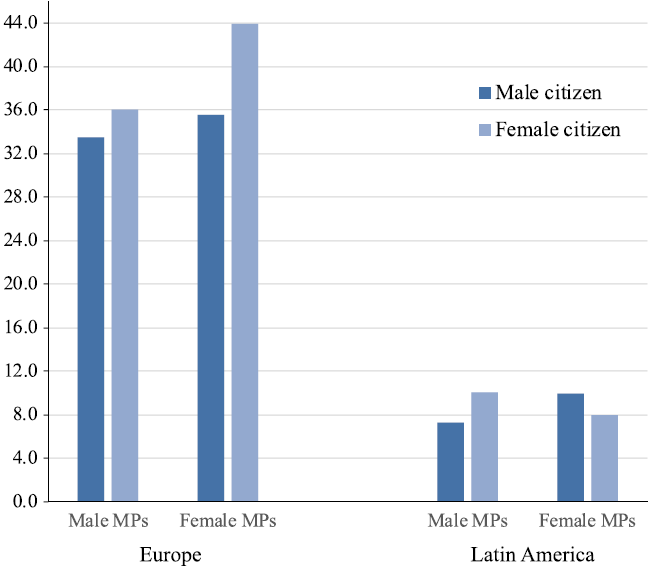

Why do women receive more responses? The answer lies in the greater responsiveness of female MPs to women. While both male and female MPs reply more to women, the difference in response rates, conditional on the constituent’s gender, is larger for female elected officials. 30.3% of female MPs replied to women, but only 25.8% replied to men (difference = 4.5% points; p-value = 0.10). In contrast, 24.5% of the male MPs replied to women, compared to 22% who replied to men (difference = 2.5% points; p-value = 0.13).Footnote 10

Further exploring regional variation, Figure 1 reveals that female MPs were more likely to reply to women than to men in Europe but not in Latin America. In Europe, the difference between the proportion of female MPs who replied to women (43.9%) and the proportion of those who replied to men (35.6%) is 8.4 % points (p-value = 0.03). In comparison, the response rate of male MPs to women is not statistically significantly different from their response rate to men (36% vs. 33.5%, p-value = 0.32). In Latin America, neither of these differences is statistically significant.

Figure 1 MPs response rate to female and male citizens conditional on MPs gender in Europe and Latin America.

NOTES: The only statistically significant difference is that between the proportion of female MPs who replied to women (43.9%) and the proportion of female MPs who replied to men (35.6%) in Europe; p-value = 0.03.

While our data do not allow us to test why our results are attenuated in Latin America, we can speculate that this is due to the fact that the connection between descriptive representation and substantive representation is still germinal in Latin American countries. Although women have achieved improved political inclusion in the region – mainly due to the implementation of gender quotas – they still struggle to achieve representation (Htun Reference Htun2016; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2018).

Conclusion

We conducted the first large-scale audit experiment in 11 countries across Europe and Latin America to evaluate gender bias in elected officials’ responsiveness to citizens seeking access to government services. We find that women are more likely to receive a reply than men (+3% points). This effect is stronger in Europe (+4.3% points). In Europe – but not in Latin America – this is due to the fact that female MPs replied more often to women (+8.4% points). Our findings differ from the results of previous audit studies on gender bias, which mostly focused on political mentorship and generally found null effects. This matters especially because the messages in our experiment concern issues that are highly relevant in each region and that crucially affect the well-being of individuals.

What should we make of the finding that female legislators exhibit positive bias toward women? In an ideal society where discrimination is absent, women and men should be equally well represented and benefit from similar responsiveness. However, women have for a long time been marginalized in politics and society. Previous observational work on gender and politics has highlighted the importance of descriptive representation to advance the substantive representation of women. Across countries, female legislators have promoted legislation advancing women’s rights and interests (O’Brien and Piscopo Reference O’Brien and Piscopo2019; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2006; Swers Reference Swers2002). Here we show that the presence of women in parliament bolsters another dimension of substantive representation, inasmuch as helping constituents access government services is a core function of elected officials. Having more women in parliament is therefore important not only because it improves public policy outcomes for women but also because it leads to higher responsiveness to women.

Our results meaningfully deviate from previous work on racial and ethnic minorities, which has found bias against minorities contacting public officials. Part of this difference could be explained by sheer numbers: women tend to be represented in parliament in greater absolute numbers than other marginalized groups. As a result, the greater responsiveness of female MPs toward women produces effects visible at the aggregate level. Women may also find allies more often than racial minorities, given the connection that most (male) MPs have with women in their lives. In this regard, work on LGBT rights suggests that the rapid increase in recent years in support for gay rights lies in personal connections with LGBT individuals, who are present in most families and across geographic and socio-economic contexts – something that usually does not happen for racial minorities (Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2017).

Our study is unique because of its geographical breadth spanning across Europe and Latin America. Most of the existing audit studies were conducted in the USA, and the vast majority of studies outside the USA were single-country experiments. The regional variation in our findings warns against taking for granted that results emerging in a specific country or region will travel to other countries. Although we find that female legislators are significantly more responsive to women in Europe, we do not find the same trend in Latin America. Future experimental work should therefore further consider the impact of different historical, institutional, and cultural contexts on the emergence of bias in the interaction between citizens and legislators.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2020.23