“Democracy must be something more than two wolves and a sheep voting on what to have for dinner.” –James Bovard (Reference Bovard1995).

In many contemporary societies, citizens and legislators use majority-rule voting to make a variety of collective decisions including choosing the president, allocating the budget, and passing laws with referendums. Voting gives citizens a say in the government and this personal involvement can increase the government’s perceived legitimacy (Esaiasson, Gilljam, and Persson, Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2012). Voting can also help rectify long-standing injustices in society by giving voice and power to marginalized groups (Acemoglu and Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012). However, voting does not always promote the common good, because a majority could make choices that disproportionally harm a minority (Sen, Reference Sen1977; Tullock, Reference Tullock1959). In recent times, the hazards of voting have been widely lamented after a series of controversial votes including the Brexit referendum and the increasing electoral success of authoritarian leaders (Norris and Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2018).

Here, we investigate the psychology of majority-rule voting: When do people think a group should use voting to make a collective decision and when is voting inappropriate? Specifically, we examine whether people think voting is less appropriate when the group includes a minority of individuals who have more at stake in the decision than those in the majority. We use scenario methods to pose participants with dilemmas in which individuals with conflicting preferences need to make a collective choice. Participants judge whether the group should decide by voting, consensus, unilateral leadership, or chance, and they rate the appropriateness of each decision rule. Across experimental conditions, we manipulate whether the group contains a minority with stronger preferences than those in the majority. We use these methods to probe people’s intuitions about voting in five countries with diverse cultures and political institutions.

People’s judgments about voting are likely to vary across cultures. Some countries like the USA have a strong ethos espousing the merits of voting which is continually reinforced beginning in early childhood. In other countries, citizens are not culturally encouraged to admire voting institutions which may play little or no role in their government (Hug and Tsebelis, Reference Hug and Tsebelis2002). Hence, we would expect people in more democratic countries to be more enthusiastic about voting as a procedure for collective choice.

At the same time, people’s judgments about voting might be shaped by an underlying psychology of group decisions that spans cultures. Across all human cultures, people live and work in groups and they frequently have to make collective decisions when individuals disagree. It is likely that the human mind includes psychological abilities for managing these collective choices, such as an ability to make quick, intuitive judgments about how a group should make a decision, and the abilities to learn and invent new rules for collective choice such as different forms of voting or leadership. These basic psychological abilities comprise a kind of intuitive political theory that shapes how people manage collective decisions (DeScioli and Bokemper, Reference DeScioli and Bokemper2019). This idea builds on an interdisciplinary literature in cognitive science about how people use intuitive theories to think, learn, and innovate in multiple domains of experience including language, mathematics, tools, relationships, and economics (reviewed in Boyer and Petersen, Reference Boyer and Petersen2012; Carey and Gelman, Reference Carey and Gelman2014).

Intuitions about the mischiefs of faction

We investigate whether people across multiple cultures exhibit a kind of Madisonian intuition that voting is less appropriate when it could harm a vulnerable minority. By a vulnerable minority, we mean a numerical minority of individuals who have more at stake in a collective decision than the majority and therefore could be disproportionately harmed by majority rule. A key insight from Madison and modern theories of social choice is that voting can do more harm than good when the majority chooses a policy that imposes disproportionate costs on a vulnerable minority (Sen Reference Sen1977; Tullock Reference Tullock1959). This problem was expressed in Madison’s (Reference Madison and Dawson1787) concerns about the “mischiefs of faction” and Mill’s (Reference Mill1869) “tyranny of the majority.” Recent research, too, examines the potential harms of voting such as when referendums threaten civil rights or ethnic minorities (Bochsler and Hug, Reference Bochsler and Hug2015; Gamble, Reference Gamble1997; Haider-Markel, Querze, and Lindaman, Reference Haider-Markel, Querze and Lindaman2007; Hajnal, Gerber, and Louch, Reference Hajnal, Gerber and Louch2002).

We test the hypothesis that across cultures people understand the problem of vulnerable minorities. The Madisonian hypothesis stems from a rich literature in psychology about how the human mind represents other people’s preferences. For example, by 24 months, children start to represent other people’s preferences as distinct from their own, such as understanding that an adult prefers broccoli over crackers even if the child prefers crackers (Repacholi and Gopnik, Reference Repacholi and Gopnik1997; Ruffman, Aitken, Wilson, Puri, and Taumoepeau, Reference Ruffman, Aitken, Wilson, Puri and Taumoepeau2018). A few years later, children gain the ability to represent the strengths of different people’s preferences, to compare preferences across individuals, and to use these comparisons to make social decisions such as whether to share toys or how to divide snacks (Pietraszewski and Shaw, Reference Pietraszewski and Shaw2015; Schmidt, Svetlova, Johe, and Tomasello, Reference Schmidt, Svetlova, Johe and Tomasello2016). By adulthood, people use these cognitive abilities to make tradeoffs between different individuals’ preferences, which guides our decisions to cooperate, share, compete, punish, and many other social behaviors (for reviews, see Balliet, Parks, and Joireman, Reference Balliet, Parks and Joireman2009; Charness and Rabin, Reference Charness and Rabin2002; Petersen, Sell, Tooby, and Cosmides, Reference Petersen, Sell, Tooby and Cosmides2012), in addition to regulating social emotions such as compassion, gratitude, anger, and forgiveness (Delton, Petersen, DeScioli, and Robertson, Reference Delton, Petersen, DeScioli and Robertson2018; Delton and Robertson, Reference Delton and Robertson2016; Sell, Tooby, and Cosmides, Reference Sell, Tooby and Cosmides2009). Like most psychological abilities, humans understand preferences intuitively, meaning that we grasp them effortlessly, automatically, and unconsciously, without requiring conscious reasoning (though intuitions may become conscious). (For a review of the primacy of intuitions in social and moral psychology, see Haidt, Reference Haidt2012 chapter 3.)

Hence, it is clear that people’s minds routinely represent other individuals’ preferences and compare the relative magnitudes of preferences to inform a variety of social behaviors. However, it is less clear whether people use this information to decide if voting is appropriate for a given group decision. In principle, people could support voting simply because it is a local convention, or because they believe it is always efficient, or they believe it is inherently fair, or for a variety of other reasons that do not depend on the strengths of individuals’ preferences. If so, then people’s support for voting will be relatively insensitive to whether a minority of individuals are more affected by the decision than others.

Alternatively, the same basic representations of preferences that guide many everyday social behaviors might also shape people’s support for voting. Thus, we hypothesize that like Madison, people across cultures recognize when a numerical minority has stronger preferences, intuitively grasp that voting could harm the minority, and thus diminish their support for voting in response. Instead, people will seek alternatives that protect minorities such as requiring a unanimous consensus. Importantly, people could benefit by avoiding harmful voting not only when they are in the minority themselves but also when they are members of a majority who could otherwise become entangled in costly conflict with a spurned minority.

Previous research found that participants in the USA judged that voting was less appropriate when the group included a vulnerable minority (DeScioli and Bokemper, Reference DeScioli and Bokemper2019). Moreover, this work builds on a broader literature in political science finding that people weigh minority interests when judging the legitimacy of voting. For example, participants judged that voting was less legitimate when it diminished women’s rights compared to protecting them, and the decision was even less legitimate when women were not adequately represented among the voters (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo, Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019). Similarly, both black and white participants judged a vote that favored white citizens to be less legitimate when fewer black citizens were among the voters (Hayes and Hibbing, Reference Hayes and Hibbing2017). Related, another line of work examines the advantages of consensus over voting. For instance, one study found that women participated more in deliberation when the group decided by consensus compared to majority rule (Karpowitz, Mendelberg, and Shaker, Reference Karpowitz, Mendelberg and Shaker2012). Another study found that participants shared money more equally in an economic game when the players had to reach a consensus (Sulkin and Simon, Reference Sulkin and Simon2001). Overall, these previous findings suggest that people – at least in the USA – weigh minority interests and group composition when judging voting.

Of course, participants in the USA might be more likely to show this pattern. From a young age, Americans learn in school about civil rights, checks and balances, and the ideas of founders such as Madison. Moreover, living in a diverse, polarized country, Americans often see debates about vulnerable minorities and which rules are most appropriate for different collective decisions. On the other hand, if Madisonian judgments stem from our basic social abilities to weigh others’ preferences, then they are likely to occur across multiple cultures.

Here, we use methods from previous research on Americans (DeScioli and Bokemper, Reference DeScioli and Bokemper2019) to examine judgments about voting in five different countries: Denmark, Hungary, India, Russia, and the USA (replicating the original). We adopt the common design that compares very different systems (Przeworski and Teune, Reference Przeworski and Teune1970). These five countries differ in numerous respects related to voting: type of political system, degree and longevity of democracy, party system, economic development, ethnic diversity, and the prominence of authoritarian leaders. Given this political diversity, we expect that participants’ support for voting will vary by country according to the cultural prominence of voting and democracy. However, our primary interest is whether people from diverse cultures judge that voting is less appropriate when there is a vulnerable minority in the group.

Method

We recruited participants at universities on campus, in classrooms, or by email (Denmark, Hungary, and Russia) and online with MTurk (USA, India). To present the same scenarios across different cultures, we worked with native speakers to translate the materials to the local language: Danish, Hungarian, and Russian (and English in India and the USA). We excluded participants who failed a simple comprehension question (n = 121; 15%), yielding a total sample of 690 participants.Footnote 1 Note, we used convenience samples (like most scientific experiments) which is appropriate because we aim to test hypotheses about participants with different political backgrounds, rather than to generalize about each country (also see Popper, Reference Popper1959, on the key difference between testing and generalizing). As expected, the samples are not representative of each country: participants are generally younger, more politically liberal, and more affluent than average (see online Appendix A).

Participants gave informed consent, read the instructions, and completed the survey on Qualtrics. Participants read three scenariosFootnote 2 about group decisions in a random order. In each scenario, a small group needs to make a collective decision even though they disagree. The scenarios depict common problems of social choice that could arise in everyday life: choosing a restaurant for dinner, choosing an activity for a day trip, and choosing how to divide the profits from selling a company. (We used three scenarios for variety, not to test for differences between scenarios.) Participants then judged whether the group should decide by voting, consensus, leadership, or chance.

As in previous research, we deliberately use scenarios about small groups and non-politicized issues in order to focus on participants’ basic judgments about voting in groups, for the moment holding aside a variety of political beliefs. Indeed, neutral scenarios may be especially useful for comparing judgments across cultures, because they help disentangle the psychology of group decisions from differences in contemporary politics across countries. This research strategy also leverages the idea that people’s understanding of national politics builds on their judgments about small groups in everyday life, such as judgments about sharing, cooperation, cheating, and leaders (Petersen and Aarøe, Reference Petersen and Aarøe2013).

Across between-subject conditions, we manipulated whether the group had a vulnerable minority – a smaller number of people with more at stake than the majority. In the vulnerable minority condition, participants read these three scenarios:

-

Dinner. A group of 10 people are deciding where to have a dinner event. Seven people want to have the event at a Japanese sushi restaurant. Three people cannot eat sushi because they have fish allergies and they want to have the event at an Italian restaurant instead. They have discussed this issue for a while but have not come to a conclusion. How should the group decide what to do?

-

Activity. A group of 10 people rented a boat and they are deciding where to go for a day trip. Seven people want to go down the river to a beach. Three people do not like the beach because they sunburn very easily, and they want to go up the river to a waterfall instead. They have discussed the issue for a while but have not come to a conclusion. How should the group decide what to do?

-

Company. A group of 10 people are selling their software company and deciding how to divide the profits. All 10 people contributed equal investments to start the company, but 3 of the people did all of the work creating and selling the software. The seven who invested without working think the profits should be divided equally. The three who did the work think they should receive a larger share of the profits. They have discussed the issue for a while but have not come to a conclusion. How should the group decide what to do?

In the control condition, participants read the same scenarios except they stated that “some” individuals preferred each option, without saying how many or indicating the magnitude of their preferences (online Appendix B). Thus, the control scenarios do not specify that there is a vulnerable minority, while the treatment scenarios add the two key ingredients for a vulnerable minority: there is a smaller number on one side of the disagreement and they have stronger preferences that make them vulnerable (allergies, sensitive skin, or greater work).

After each scenario, participants answered how the group should decide: voting, consensus, leadership, or chance (with brief descriptions of each, see online Appendix B). Participants also rated the appropriateness of each decision rule on a seven-point scale from very inappropriate to very appropriate (coded −3 to +3). Finally, participants answered demographic questions about their age, sex, and political ideology.

We first examine whether participants’ preference for voting varies across countries. We then test the Madisonian hypothesis that participants will reduce their support for voting when the group contains a vulnerable minority compared to the control scenario.

Results

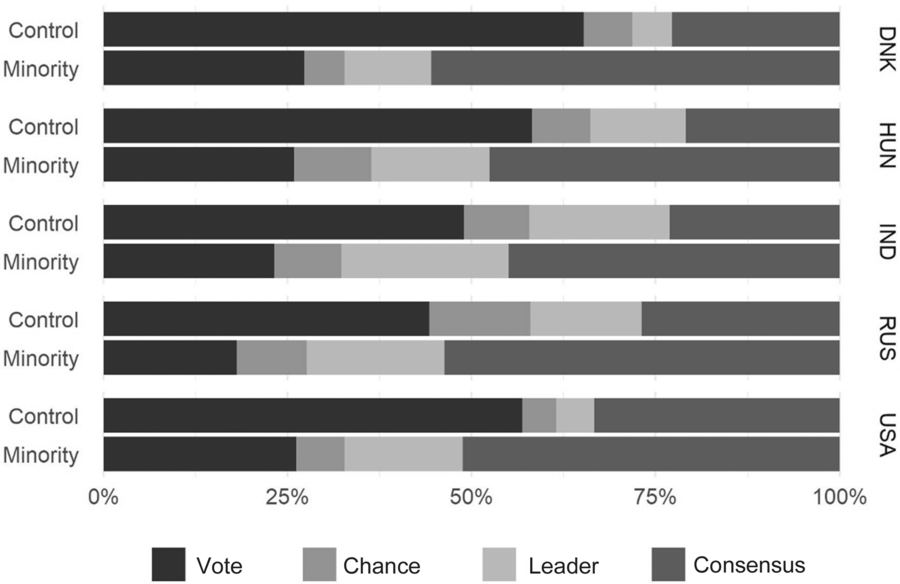

We combine the three scenarios to determine each participant’s percentage of choosing each decision rule. For instance, a participant who chose voting in two scenarios and consensus in the third is summarized as 67% voting, 33% consensus, and 0% for leadership and chance. We analyze the mean percentages across participants with simple statistical tests (ANOVAs and t-tests). Figure 1 shows participants’ choices by country.

Figure 1 Participants’ choices of decision rules by experimental condition (control or vulnerable minority) and country. The results show a high preference for voting (black bars aligned left) in the control condition, which was substantially diminished when a vulnerable minority was present in the group. Meanwhile, participants’ preference for consensus (darkest grey shade aligned right) tended to increase with the addition of a vulnerable minority.

We first examine preferences for voting in the control condition without a vulnerable minority. As expected, participants’ preferences for voting varied by culture, F(4,349) = 6.56, p < .001. The lowest support for voting is in Russia (M = 44%), which is the only non-democratic country in the study, and next is India (M = 49%), a new democracy. We find more support for voting in the USA (M = 57%) and Denmark (M = 65%), established democracies, and somewhat surprising, Hungary (M = 58%), a new and struggling democracy. This pattern broadly mirrors the levels of democracy in these countries (Freedom House’s Democracy scores, see online Appendix C). Broken down by scenario, participants from all five countries chose voting most often for the Dinner and Activity scenarios, while consensus was most frequent for the Company scenario (see online Appendix C).

Next, we turn to the main experimental prediction about vulnerable minorities. Participants’ preferences for voting (Figure 1) decrease when there is a vulnerable minority compared to the control condition. Aggregating across scenarios and countries, participants were significantly less likely to choose voting when there was a vulnerable minority (M = 23%) compared to the control condition (M = 54%), t(674) = 14.47, p < .001. Further, this treatment effect occurred in all five countries: Denmark, ΔM = −38%, t(125) = 6.33, p < .001; Hungary, ΔM = −32%, t(109) = 6.43, p < .001; India, ΔM = −26%, t(88) = 5.02, p < .001; Russia, ΔM = −26%, t(189) = 8.83, p < .001; and USA, ΔM = −31%, t(111) = 5.45, p < .001. Moreover, we find in a two-way ANOVA no significant interaction between country and the vulnerable minority treatment, F(4, 680) = 0.37, p = 0.32. Hence, we find support for the Madisonian hypothesis.

Meanwhile, participants’ preferences for consensus increase with the addition of a vulnerable minority (Figure 1). In aggregate, participants were more likely to choose consensus when there was a vulnerable minority (M = 51%) than in the control condition (M = 25%), t(667) = 11.33, p < .001. Indeed, with a vulnerable minority, consensus became the most common choice. Again, this treatment effect occurred in all five countries: Denmark, ΔM = 33%, t(103) = 5.44, p < .001; Hungary, ΔM = 27%, t(93) = 5.08, p < .001; India, ΔM = 22%, t(111) = 4.04, p < .001; Russia, ΔM = 27%, t(205) = 7.52, p < .001; and USA, ΔM = 18%, t(112) = 3.06, p < .01. And, we find no significant interaction between country and the vulnerable minority treatment, F(4, 680) = 0.39, p = 0.33.

In online Appendix C, we report additional analyses broken down by scenario and country, and with multilevel models, further confirming that participants preferred voting less and consensus more when there was a vulnerable minority, supporting the Madisonian hypothesis.

Discussion

Overall, we find support for the Madisonian hypothesis that people diminish their preference for voting when the group contains a vulnerable minority. In general, participants from five diverse countries frequently chose voting as the best rule for resolving conflicting preferences. As expected, support for voting also varied across countries, approximately following the nation’s level of democracy. Among this variation, we also found a consistent theme across countries: Participants showed less support for voting when there was a vulnerable minority compared to the control condition. With a vulnerable minority, participants shifted their preference to consensus, which is revealing because consensus inherently protects minority interests. This pattern occurred in all five countries despite substantial differences in culture and political institutions.

Perhaps also noteworthy, relatively few participants chose leadership to resolve the group’s disagreement. Even in countries with more authoritarian leaders (Russia, Hungary), most participants generally favored voting and then switched to consensus when there was a vulnerable minority.

This experiment has a number of limitations that can be expanded upon in future research. For instance, participants did not have a personal stake in the conflicts, which would likely bias them toward whichever rule favors their interests (DeScioli, Massenkoff, Shaw, Petersen, and Kurzban, Reference DeScioli, Massenkoff, Shaw, Petersen and Kurzban2014). This could potentially override their Madisonian judgments causing them to favor voting when they are in the majority, even if it harms a vulnerable minority. At the same time, many people cooperate with others and so may sympathize with numerical minorities. Future research could extend the current methods to study participants’ decisions when they are among the majority, and also when people think a majority is more likely to defer to a vulnerable minority (prior to a disagreement).

We purposefully used interpersonal scenarios unconnected to current politics, which we regard as a crucial initial step. Future research can build on this foundation to address current political issues, such as whether referendums are appropriate to settle policy debates over health care, rent control, or immigration. We can also investigate how partisanship and ideology affect citizens’ Madisonian sympathies toward different minority groups in society. Finally, we used convenience samples from each country, including recruiting some participants at universities and some online. While the samples offer an appropriate test of hypotheses about vulnerable minorities, they are not well-suited for making strong generalizations about each country as a whole or differences between these countries. Future research can use representative samples to better characterize each country and to look more closely at variation within and between countries.

Mindful of these limitations, the current findings provide important initial insight into how people judge the legitimacy of voting as a rule for resolving disagreements in society. The results support the broader theory that people have distinct intuitions about how groups should make decisions in different situations (DeScioli and Bokemper Reference DeScioli and Bokemper2019). When these expectations are violated, people generally perceive the resulting decisions as less legitimate (Hibbing and Alford, Reference Hibbing and Alford2004). More specifically, like Madison and Mill, citizens might view voting as illegitimate when a minority could be considerably harmed by a vote. If so, these political intuitions could undermine the legitimacy of voting for deciding highly divisive issues with vulnerable minorities – such as the Brexit vote (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2016). To recall the opening quote, people appear to intuitively understand that voting does not always protect a minority of sheep from a majority of wolves, calling for discernment about the kinds of collective decisions for which voting is best suited.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Gábor Simonovits and the members of the Political Behavior Workshop at Aarhus University for helpful comments. We are indebted to Zsófia Papp, Anna Vancsó, Anna Csonka, Ekaterina Lytkina, Lyudmila Igumnova, and many others for their research assistance in Hungary and Russia. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2020.8