“Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field right now. Out! He’s fired. He’s fired!’” – Donald Trump, September 23, 2017

On August 14, 2016, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick bucked tradition by remaining seated on the bench, rather than standing, for the national anthem during a pre-season football game. Once the media started covering this, Kaepernick, who is multi-racial and identifies as Black, announced that he remained seated during the anthem to protest police brutality against African-Americans. Over the ensuing weeks and months, Kaepernick’s protest evolved, and numerous other players joined with him in the anthem protests. By the start of the next season, Kaepernick was no longer employed by an National Football League (NFL) team, but the protests continued, attracting significant media attention and both support and opposition from the public and political elites. Anthem protesters were certainly interested in drawing attention to causes they viewed as important, but did so in a civil, non-disruptive way. However, their actions attracted vitriol from certain members of society, culminating with a harsh rebuke from the President.

Early in the 2017 NFL season, President Donald Trump made the above comments at a political rally in Alabama, drawing nationwide attention. Trump’s rhetoric, calling those protesting the anthem a “son of a bitch,” shows not only opposition to players protesting the anthem, but also dehumanizes these players by comparing them to dogs. That week, New York Giants wide receiver Odell Beckham Jr. pantomimed a dog in a touchdown celebration,Footnote 1 signifying that Trump’s dehumanizing message was heard loud and clear by NFL players.

Dehumanizing language that compares humans to animals – referred to by psychologists as “animalistic dehumanization” – serves to deny human status towards groups that are dehumanized by denying traits that are considered uniquely human – traits like reason, critical thinking, and emotions (Haslam Reference Haslam2006; Leyens et al. Reference Leyens, Paladino, Rodriguez-Torres, Vaes, Demoulin, Rodriguez-Perez and Gaunt2000). Originally, dehumanization was seen as a way to deny humanity to groups to justify violence against these groups (Kelman Reference Kelman1973), but has since been shown to cause punitive attitudes towards a variety of groups, such as immigrants (Utych Reference Utych2018), African-Americans (Goff et al. Reference Goff, Eberhardt, Williams and Jackson2008), terrorists (Waytz and Epley Reference Waytz and Epley2012), and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender + individuals (Fasoli et al. Reference Fasoli, Paladino, Carnaghi, Jetten, Bastian and Bain2016).

As a group, athletes, and especially Black athletes, have been traditionally dehumanized (see Coombs and Cassilo Reference Coombs and Cassilo2017). This language, even if it has generally positive connotations in sport, can serve to make individuals think of Black athletes as something less than human. By using dehumanizing language against NFL anthem protesters, nearly all of whom are Black, Trump may be able to create negative and punitive attitudes towards these protesters among White Americans, above and beyond what he could do by using language that is simply negative towards the protesters.

Is the use of dehumanizing language more effective than simply negative language at getting citizens to disapprove of anthem protests? As a group, athletes are frequently dehumanized (Hoberman Reference Hoberman1992), which may make additional dehumanization difficult. I examine how dehumanization of a national anthem protester influences individual attitudes about the protests. Using original experimental data, I present individuals with information about a famous athlete joining the anthem protests. When doing this, I vary the race of the athlete (White vs. Black) and vary the language used to describe the athlete (dehumanizing vs. non-dehumanizing). I find that dehumanization does lead to more negative attitudes towards anthem protests, among White Americans, but only when the dehumanized athlete is Black. When the dehumanized player is White, there is no effect of dehumanization on attitudes towards anthem protesters. This suggests that dehumanization only operates, in the context of the anthem protest, against racial out-groups, which has troubling implications for how humanity can be denied to racial and ethnic minorities.

Dehumanization, politics, race, and sports

Dehumanization allows individuals to justify discrimination and prejudice towards out-groups (Bandura 1999). Dehumanization operates by comparing human beings to non-human entities – this can serve to deny individuals uniquely human traits such as cognition, affect, and behavior (Tipler and Ruscher Reference Tipler and Ruscher2014). When an individual or group is dehumanized, people see them as less capable of understanding that they are being treated poorly, making them more likely to prefer a harsh punishment of dehumanized individuals for some transgression (Bandura, Underwood, and Fromson Reference Bandura, Underwood and Fromson1975). Dehumanization is powerful – it is not simply language that makes one feel negatively towards a group, but it denies that group important elements of what makes them human.

Dehumanization is not a new phenomenon. During World War II, Nazi Germany frequently dehumanized Jewish people as vermin or disease, and the United States dehumanized the Japanese as apes, which created a moral justification for extreme violence against these groups (Dower Reference Dower1986; Russell Reference Russell1996). This type of dehumanization occurred quite blatantly, typically through propaganda posters. More recently, dehumanization has been studied in more subtle ways. Immigrants are often dehumanized as a contagion (Cisneros Reference Cisneros2008; Esses, Medianu, and Lawson Reference Esses, Stelian and Lawson2013), while ape-like language is often used to describe African-Americans accused of murder (Goff et al. Reference Goff, Eberhardt, Williams and Jackson2008).

When dehumanizing language is used, there are often serious attitudinal consequences. Dehumanization predicts support for the use of torture against those accused of terrorism (Waytz and Epley Reference Waytz and Epley2012). Dehumanizing language also predicts more restrictive immigration policies, caused by increased responses of anger and disgust towards immigrants (Utych Reference Utych2018), and those higher in disgust sensitivity exhibit greater negative attitudes towards immigrants (Costello and Hodson Reference Costello and Hodson2007). Dehumanization also leads to a decrease in empathy towards groups that are dehumanized (Costello and Hodson Reference Costello and Hodson2010; Stevenson et al. Reference Stevenson, Malik, Totton and Reeves2015). Dehumanization can also lead to implicit biases towards groups, which are often quite difficult to counteract (Mekawi et al. Reference Mekawi, Konrad and Hunter2016).

Certain groups are easier to dehumanize than others. When groups are socially distant, they are easier to dehumanize (Waytz and Epley Reference Waytz and Epley2012). As groups become more different from an individual, those groups are more readily dehumanized (Leyens et al. Reference Leyens, Paladino, Rodriguez-Torres, Vaes, Demoulin, Rodriguez-Perez and Gaunt2000). There is a correlation between viewing those from other social groups as subhuman, and preferences for punitive action against these groups (Kteily et al. Reference Kteily, Bruneau, Waytz and Cotterill2015). Citizens are also more prone to dehumanize members of the out-party, rather than co-partisans (Cassese Reference Cassese2019; Martherus et al. Reference Martherus, Martinez, Piff and Theodoridis2019). In general, as a group becomes less like an individual, that individual should be more willing to dehumanize that group, and accept dehumanizing messages about that group.

While most instances of dehumanization are inherently negative, athletes are often dehumanized in ways that serve to praise their abilities, while denying them their human traits. Athletes are frequently dehumanized by discussing their value in pure statistical or monetary terms (Grano Reference Grano2014; Hoberman Reference Hoberman1992). Black athletes, as a group, are frequently treated as commodities, rather than as human beings (Griffin Reference Griffin2012). Athletes are frequently described as “beasts,” which, while positive towards their athletic ability, is dehumanizing (Beasley, Miller, and Cokley Reference Beasley, Miller, Cokley, Moore and Lewis2014).

Black athletes, especially, are likely to be dehumanized, even when those athletes are among the elite in their sport (Hyland Reference Hyland2014). Athletes are described as “assets,” suggesting their incredible value to their teams, or “beasts,” otherworldly creatures who achieve feats that few humans can. Black athletes are frequently interpreted as less intelligent, and more aggressive and arrogant, than White athletes (Brown Reference Brown, Hawkins, Carter-Francique and Cooper2017). The media typically focuses coverage of Black athletes on their physical, rather than intellectual, traits (Carrington Reference Carrington2010), while White athletes are often praised for uniquely human traits, such as their work ethic and intelligence (Eastman and Billings Reference Eastman and Billings2001). Indeed, even the mascots of sporting teams are often racially insensitive towards marginalized groups in society (Conley and Hawkins Reference Conley and Hawkins2015). Amateur prospects are literally measured, with team executives and fans fawning over their size, strength, agility, and speed. While generally positive towards the athletes, these evaluations tend to limit their humanity – Jeffrey Lane notes that “Black [athletes] become … something other than human beings” in the context of how they are evaluated in sports (Reference Lane2007, p. 66).

Even when designed to praise, positive dehumanization denies important human traits to individuals, which can serve to deny them their humanity, and have important negative consequences. These seemingly positive stereotypes can imply negative connotations – saying a Black athlete is athletically gifted may suggest that the athlete does not have to work hard, employing the stereotype of Black people as lazy (McCarthy and Jones Reference McCarthy and Jones1997). In the context of the workplace, positive dehumanization causes individuals to view employees as better workers, but evaluate them more negatively on personal characteristics, like friendliness and warmth (Utych and Fowler Reference Utych and Fowler2020). National Collegiate Athletic Association sports medical staff members perceive Black athletes as having a higher tolerance for pain than White athletes (Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Sophie, Ivonne, Fredendall, Kanter and Rubenstein2018), perhaps due to the casual dehumanization of Black athletes. It is clear that dehumanization, even when used in a positive light, still denies humanity towards dehumanized individuals, and has important negative consequences.

This dehumanization of Black athletes connects to broader implications in American politics. One of the clearest and most long-standing group divisions in American politics is based on race – specifically, between White and Black Americans. Dehumanizing language used against Black athletes, and Black people in general, can help to fuel this divide. Even when dehumanizing language is used positively, it tends to compare Black athletes to animals, a common dehumanizing connection for Black people throughout history (see Goff et al. Reference Goff, Eberhardt, Williams and Jackson2008). While sports, and the anthem protests, are an important issue where racial divides should be prevalent, reactions to these protests can relate to long-standing racial divisions in American politics.

Racial attitudes predict a host of political attitudes (Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996), and have increasingly done so since the election of Barack Obama as president (Kinder and Dale-Riddle Reference Kinder and Dale-Riddle2012; Tesler Reference Tesler2016). Traditionally, White people view policies that benefit Black people as those that will also harm White people (Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996). During the Obama presidency, racial attitudes were shown to predict changes in seemingly race-neutral policies (Lundberg et al. Reference Lundberg, Payne, Josh and Krosnick2017), suggesting that race plays an even larger role in politics today. Racial identity becomes salient and political when those in a group perceive threats from out-groups (Huddy Reference Huddy, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013). Given that the anthem protests were undertaken in order to protest police violence against Black Americans, typically perpetrated by White police officers, this issue seems primed to divide White and Black Americans into groups on opposite sides of the issue.

Responses of the public towards the anthem protests do seem to divide along racial lines. Black Americans are more supportive of all types of anthem protest, and are less supportive of punishments for those who protest the national anthem (Intravia, Piquero, and Piquero Reference Intravia, Piquero and Piquero2018). Individual differences, such as propensity to make attributions to prejudice, and adherence to masculine honor beliefs, predict increased negative attitudes towards Black players who protest the national anthem (Stratmoen, Lawless, and Saucier Reference Stratmoen, Lawless and Saucier2019). This racial divide extends to other areas of sports, as non-White people were considerably more likely than White people to view Atlanta Falcons’ quarterback Michael Vick’s 2007 punishment for dog fighting as too harsh (Piquero et al. Reference Piquero, Nicole Leeper, Marc, Thomas, Jason and Barnes2011). Even when Black athletes, such as LeBron James, are seen as reasonable and intelligent voices on social issues, they are often criticized by the media (Coombs and Cassilo Reference Coombs and Cassilo2017). Due to stereotyping of Black athletes, they are often reprimanded by the public for advocating for political causes (Kaufman Reference Kaufman2008). Importantly, however, there is evidence to suggest that Colin Kaepernick’s protests were able to mobilize Black Americans to participate in politics at higher levels (Towler, Crawford, and Bennett Reference Towler, Crawford and Bennett2019). This suggests that how individuals view Black people in the world of sports is similar to the divide between Black people and White people in society at large.

Existing work shows that minority groups are more likely to be dehumanized than majority groups, and that this divide is especially prevalent among race. In athletics, dehumanizing language is frequently used against Black athletes, but not as commonly referring to White athletes. There is also a racial divide among the public – Black citizens tend to view Black athletes, especially activist Black athletes, more favorably than White citizens. By using the case of the NFL’s national anthem protests, I am able to connect these literatures by examining how race and dehumanization intersect. I predict that dehumanizing Black athletes will be effective at causing fans of the NFL to be less supportive of national anthem protests by players, but dehumanizing a White athlete will not have this effect.

Study 1 – Dehumanization and anthem protests with real NFL players

Participants were recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (mturk) in May 2018.Footnote 2 Participants were paid 50 cents for participating in a survey on public opinion and the NFL that took roughly 4–5 minutes to complete. RecruitmentFootnote 3 indicated that participants must consider themselves a fan of the NFL to participate in the study.Footnote 4 A total of 1,167 individuals participated in this study, among whom 878 identified as White.Footnote 5 Since NFL fans were recruited, the participants were highly male (62.64%). Of the White sample, participants ranged in age from 18 to 80, with a mean age of about 37. Roughly 51% of the sample identified as Democrats, 38% Republican, and 11% independents. About 57% of the sample had a bachelor’s degree or higher. While this sample is younger, more Democratic, and more educated than the U.S. population at large, mturk samples have been shown to compare favorably to nationally representative samples in conducting political science research (Clifford, Jewell, and Waggoner Reference Clifford, Jewell and Waggoner2015).Footnote 6 In fact, the liberal nature of this participant pool may make this a harder test, as conservatives tend to be much less supportive of the national anthem protests (Intravia, Piquero, and Piquero Reference Intravia, Piquero and Piquero2018).

In the study, participants were asked a series of demographic questions, and then randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups. In these groups, individuals read a fictional news story about an NFL player announcing they would protest the national anthem during the upcoming 2018 NFL season. The raceFootnote 7 of the player was varied between Black (Dallas Cowboys quarterback Dak Prescott) and White (Oakland Raiders quarterback Derek Carr).Footnote 8 Additionally, the language used in the article to describe the player varied between dehumanizing and non-dehumanizing. The full treatment textFootnote 9 is presented below.

[Oakland Raiders/Dallas Cowboys] quarterback [Derek Carr/Dak Prescott] has recently announced that he will join other players in protesting police violence by kneeling for the national anthem during the 2018 NFL season. [Carr/Prescott], who is [White/Black], is the highest profile player to date who has announced he will join the protests. “I appreciate the other players who have taken action to protest police brutality, and I have decided to join with them next season by kneeling during the national anthem. We haven’t seen any change yet, and I want to be an example to everyone out there that peaceful protest can change society,” [Carr/Prescott] said in a statement released this morning.

[Carr/Prescott]’s announcement has not been received warmly. [California/Texas] Representative Josh Evans denounced [Carr/Prescott]’s decision. “If I was the team [owner/executive], I’d be furious. This [rat/jerk] thinks this is good for the team? This disrespect of our flag and military needs to be [exterminated/stopped]. The league is [eradicating cancers/getting rid of players] like this, and I hope this [animal/guy] is next.”

An anonymous teammate disagrees with [Carr/Prescott]’s stance, but doesn’t think that will affect performance on the field. “I don’t agree with what he’s doing, but [Derek/Dak] is a [beast/great player]. He might be an activist off the field, but on the field, he’s a [monster/football player]. He’s an [asset/leader] for our team – his [athleticism/intelligence] is going to help us win games.”

This treatment allows me to isolate the effects of both race and dehumanization on attitudes towards anthem protests. Carr and Prescott were chosen since, while Carr is White and Prescott is Black, they play the same position, and are rated similarly in terms of their ability as quarterbacks,Footnote 10 and neither had taken a public stance on the anthem protests at the time of the study.Footnote 11 The dehumanizing language covers a variety of types of dehumanization, which is sometimes negative (calling the player a rat or cancer) and sometimes positive (calling the player an asset or beast). A focus on athletes also allows for dehumanization that is not wholly negative, as athletes are frequently dehumanized as “beasts” or “assets” in ways that have a positive connotation.

After the treatment, participants were asked questions about their attitudes towards anthem protests. Participants were asked to agree or disagree with the following statements on a seven-point scale, where higher values indicate stronger agreement – “I support NFL players protesting police brutality by kneeling or raising a fist during the national anthem,” “The NFL should punish players who refuse to stand for the national anthem,” and “NFL players who protest the national anthem are disrespecting the American military.”

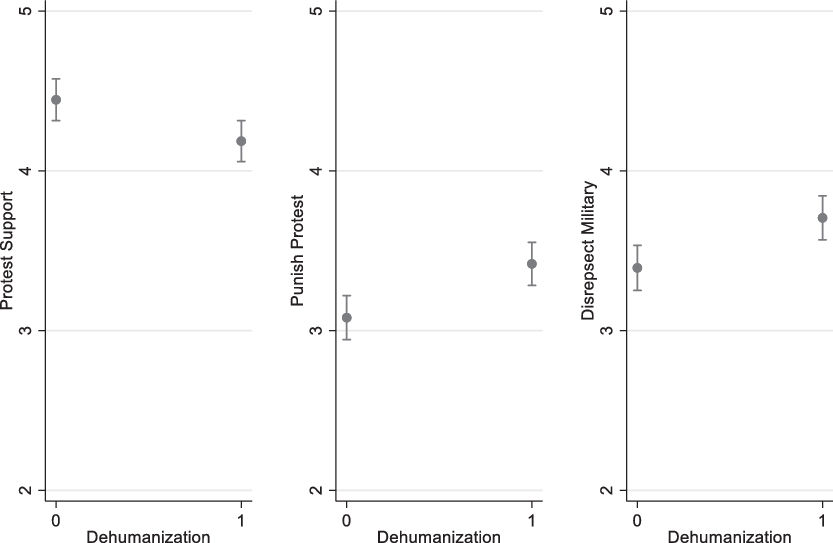

Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate how the dehumanization treatment influences attitudes towards anthem protesters.Footnote 12 When the dehumanized player is White, there is no statistical difference between the dehumanization and non-dehumanization groups on any of the three dependent variables. This suggests that dehumanization is significantly less effective for a player of one’s racial in-group.

Figure 1 Effect of Dehumanization – Derek Carr.

Figure 2 Effect of Dehumanization – Dak Prescott.

Dehumanization has a clear and consistent effect when the dehumanized player is Black. Those in the Prescott dehumanization group are marginally less supportive of anthem protests, more supportive of punishment for anthem protesters, and more likely to believe that anthem protesters are disrespecting the military. These effects are typically quite small, about 1/3 of a scale point on the seven-point scale for each variable, but this is similar in magnitude to previous effects of dehumanization on political attitudes (see Utych Reference Utych2018).

This suggests that dehumanization is effective at making people feel more negatively towards anthem protests, but only when the dehumanized individual is a member of a racial out-group, rather than a racial in-group.Footnote 13 When a dehumanized player is a member of one’s own racial in-group, effects are not distinguishable from zero, and occur in the opposite direction of expectations and effects for the player from a racial out-group.

This study, however, comes with some substantial limitations. By focusing only on NFL fans, individuals may have higher levels of information about the protests generally, or about the players involved.Footnote 14 In general, the focus on real players may introduce confounding factors into the analysis, based on the extent to which Carr and Prescott may be viewed differently in relation to the anthem protests.Footnote 15 Both Carr and Prescott came out against the anthem protests in the summer of 2018, after the study was conducted. Additionally, the negative comments about each player included statements from a fictional Congressman from their team’s home state. However, with a variation between Texas for Prescott and California for Carr, this may have inadvertently sent partisan cues about support for protests. The presence of both positive and negative dehumanization may also prove problematic – it is not clear that these types of dehumanization necessarily operate in the same way, which may introduce a confounding effect. To this end, I turn to an additional study where the sample allows any individual to participate, and players are fictional.

Study 2 – Dehumanization and anthem protests with fictional players

Participants were recruitedFootnote 16 from mturk in February 2019. Participants were paid 35 cents for participating in a survey on public opinion that took roughly 2 minutes to complete, on average. As with the previous study, only White participants were retained for analysis, providing a total of 759 respondents. Participants were 52.7% male, and ranged in age from 19 to 83, with an average age of about 41. Roughly 59.5% of the sample identified as Democrats, 31% Republican, and 9.5% independents. About 58% of the sample had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

In the study, participants were asked a series of demographic questions, and then randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups. In these groups, individuals read a fictional news story about a high school football player who began protesting the national anthem by kneeling during the current football season. The player’s race was varied primarily through their names, DeAndre Washington for the Black player, and Jacob Schmidt for the White player. Additionally, the language used in the article to describe the player varied between dehumanizing and non-dehumanizing, and the non-dehumanizing language was kept to be negative.Footnote 17 The full treatment textFootnote 18 is presented below.

Central High School [Panthers/Cowboys] Quarterback [Jacob Schmidt/DeAndre Washington], the 3rd ranked recruit in the nation, according to rivals.com, has attracted attention recently for his actions off the field. Following the lead of NFL players, including Colin Kaepernick, [Schmidt/Washington], who is [White/Black], has begun kneeling during the national anthem this season. “NFL players are doing a lot to protest racial injustice, and I have decided to join with them this season by kneeling during the national anthem. I want to be an example to everyone out there that peaceful protest can change society,” [Schmidt/Washington] said in a statement released this morning.

[Schmidt/Washington]’s announcement has not been received warmly. An anonymous college coach, whose team considered recruiting [Jacob/DeAndre], denounced his decision. “If this [cancer/athlete] was on my team, I’d be furious! This [rat/jerk] thinks this is good for the team? It’s going to [infect/affect] the other players, for sure. This disrespect of our flag and military needs to be [exterminated/stopped]. Football is [eradicating cancers/getting rid of players] like this, and I hope this [animal/guy] is next.”

Post-treatment, participants were asked the same three questions from study 1 about the NFL anthem protests – whether they support the protests, whether the NFL should punish protesters, and whether protests disrespect the military. These again were asked on a seven-point scale, with higher values indicating stronger levels of agreement with each statement. Results of these analyses are presented in Figures 3 and 4.Footnote 19

Figure 3 Effect of Dehumanization – White Player.

Figure 4 Effect of Dehumanization – Black Player.

These results once again demonstrate a consistent effect of dehumanizing language when used against a Black player. When the hypothetical player is Black, those exposed to dehumanizing language are less supportive of the protests, more supportive of punishment for the protesters, and more likely to believe the protests disrespect the military. These results are mostly similar in magnitude to study 1, but slightly larger – about 1/2 of a scale point on the seven-point scale. When the dehumanized player is White, these differences do not emerge, and dehumanization does not predict attitudes towards anthem protests.

Taken together, these studies provide evidence that dehumanization of individuals is effective at influencing political attitudes,Footnote 20 but only when this dehumanization occurs against a member of a racial minority group, among White respondents.Footnote 21 These effects persist across both real and fictional individuals, and occur both when dehumanization has mixed positive and negative connotations, and when it only has negative connotations.

Summary and conclusion

I find that dehumanizing language is effective at getting White citizens to be less supportive of national anthem protests, but only when the target of the dehumanization is Black player. Those who read about a Black player joining the anthem protests are less likely to support the protests, and more likely to support punishment of players protesting and believe that protests disrespect the military, than those who are not. While these effects are generally somewhat small, they are similar or larger in magnitude than the direct effects of varying the race of the player who is protesting.

These effects do not persist when the dehumanized player is White, where effects are largely indistinguishable from zero, and are often signed in the opposite direction. This provides some compelling evidence that dehumanization of one’s own in-group operates differently than dehumanization of an out-group. This could be because dehumanization of majority groups is relatively uncommon, while it is significantly more common towards minority groups. It could also occur because individuals reject dehumanizing rhetoric targeted at groups they are a member of. Further research is needed to determine how dehumanization of one’s in-group, or of a majority group, operates.

This work has implications for the broad study of dehumanization in politics and society at large. I demonstrate that dehumanizing rhetoric has important implications for political attitudes, and that this rhetoric is only effective when targeted at a member of a minority group, who is also a racial out-group. Given that political rhetoric has become increasingly dehumanizing, it is important to understand its consequences, and to understand who can be dehumanized. This work also has implications for the study of race in politics, suggesting that dehumanizing rhetoric is especially powerful when used against racial minorities. While the anthem protests are certainly a racialized policy area, politics as a whole are becoming increasingly racialized (Tesler Reference Tesler2016), suggesting that these effects may persist across policy areas.

Understanding dehumanizing rhetoric is important in all political climates, and perhaps especially the current one. Donald Trump’s language against racial and ethnic minorities is frequently dehumanizing, perhaps with a goal of encouraging support for punitive and harmful policies towards these groups. At its most extreme, dehumanization is a fundamental component of morally abhorrent events like mass genocides (see Dower Reference Dower1986), and citizens should be aware of the use of dehumanizing language, and the potential it has for harmful effects on the type of policies it may cause them to support. While dehumanization of professional athletes may not have these most extreme and damaging direct consequences, chronic dehumanization of marginalized groups in society could easily lead to support for policies that are otherwise morally unjustifiable.

Further work is needed to address how dehumanization operates against majority groups. Is dehumanization not effective against a White player because he is White, or because he is a member of the respondents’ racial in-group? Unfortunately, in the current studies, I do not have a large enough sample of African-Americans to make statistical inferences about how dehumanization influences their attitudes.Footnote 22 Further work, with a larger pool of Black respondents, could address how dehumanization of minority groups operates among minorities.

It is also unclear how dehumanization and partisanship may interact. While I find that Republicans and Democrats are both likely to report more negative attitudes towards dehumanized black players in Study 1, I find the effects are driven a bit more by Democrats in Study 2. This suggests that people are not simply dehumanizing people who take stances they disagree with, but that it is operating on some other plane. Importantly, the assumed partisanship of the player in each of these is likely to be Democratic, meaning I am unable to draw conclusions about how dehumanization, partisanship, and race interact with the current studies.

Additionally, it is important to consider the extent to which dehumanization, per se, is driving these results. One could argue that the dehumanization treatments here are more violent, or more negative, than the non-dehumanizing treatments. This is a fair point, and one that is difficult to address with treatment design – dehumanizing language is, by its very nature, often more negative than non-dehumanizing language. However, previous work shows that dehumanizing language predicts particular negative emotions, like anger and disgust, that simple negativity would not (Utych Reference Utych2018). Additionally, dehumanizing language causes individuals to deny dehumanized individuals human nature and human uniqueness traits (Utych and Fowler Reference Utych and Fowler2020), suggesting that dehumanization is the appropriate mechanism for at least part of these differences. Importantly, a treatment that is simply more negative should operate on White and Black individuals equally – that is, while dehumanization is a theory about how individuals feel towards out-groups, negativity should affect all groups in a similar way. This suggests, but does not unequivocally demonstrate, that dehumanization itself, rather than negativity, is driving these results.

However, this study suffers from a lack of available variables to test this mechanism, as standard measures of dehumanization were not included as a manipulation check. While work has shown that language treatments can cause dehumanization (Utych and Fowler Reference Utych and Fowler2020), this study is unable to examine that. However, existing research does show that White respondents are more likely to see non-White, compared to White, individuals as less than human (Kteily et al. Reference Kteily, Bruneau, Waytz and Cotterill2015), suggesting that dehumanizing language may serve to simply not dehumanize the White players, as it does for Black players. This is a compelling explanation for these results, and one that requires more empirical evidence to adjudicate.

As dehumanization becomes an increasingly relevant part of social and political life, it is important to understand its broad ranging consequences. When Donald Trump uses dehumanizing language to describe professional athletes protesting the national anthem (or, more recently, undocumented immigrants), there are real attitudinal consequences for the public, especially since dehumanized groups are so often racial or ethnic minorities. In the context of the anthem protests, while there was an initial backlash from those in the NFL to Trump’s dehumanizing comments, the NFL attempted to ban anthem protests in May 2018, and the amount of protests during the most recent season have been reduced to a small handful of players. Colin Kaepernick has not been employed by an NFL team since becoming a free agent after the 2016 season. While there are a lot of factors at play, many beyond dehumanizing language, in how the anthem protests and Kaepernick’s career have proceeded, an erosion of public support for his protests could make it easier for NFL team owners to refuse to sign him.

The use of dehumanizing language extends far beyond the NFL, and attitudes towards NFL players may as well. The dehumanization of Black athletes as animals (Lane Reference Lane2007) dovetails with the dehumanization of other Black Americans as animals, such as in the criminal justice system (Goff et al. Reference Goff, Eberhardt, Williams and Jackson2008). Black athletes are among the most well-known Black celebrities in America, and perhaps especially so among White Americans given their connection to sports. Since racial attitudes often have a spillover effect (Tesler Reference Tesler2016), it is likely that creating negative attitudes towards Black athletes can foster negative attitudes towards Black people in general, causing a further racial divide in American society.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2020.33