Introduction

The effect of emotions on politics is a challenging topic due to the inherent complexity of emotions and of measuring them. Typically, scholars use some form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), a scale originally developed to measure generalized positive and negative affect (Watson, Clark, and Tellegen Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988) by loading all elements of a positive or negative affect onto a single factor. This provides strong correlations between all positive and negative emotions. The correlation between discrete negative emotions, such as fear, hostility, distress, and nervousness, allows us to posit the existence of a generalized negative affect (i.e., “feeling bad”) (Watson and Tellegen Reference Watson and Tellegen1985); unfortunately, the same strong correlations that make the PANAS effective at measuring general affect indicate that it does a poor job of discriminating between discrete emotions with similar affective direction (Watson, Clark, and Tellegen Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988).

However, as recent research on emotions has uncovered that two dimensions of negative affect, anger/aversion and anxiety/fear,Footnote 1 have distinct impacts on political behavior (Albertson and Gadarian Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015; Brader Reference Brader2005; Lerner and Keltner Reference Lerner and Keltner2000; Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000), we have a disconnect between measurement and theory. Now, PANAS is being asked to do things for which it was never intended (measuring multiple discrete emotions), and there is evidence that it is an imperfect tool for this new task (see Harmon-Jones, Bastian, and Harmon-Jones Reference Harmon-Jones, Bastian and Harmon-Jones2016).

While alternative measures of emotion have been developed (see Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2017), these typically occur in situations where one expects participants to either evince one specific discrete emotion. The real world, however, is not always so clean. Take the example of the 2008 global financial crisis. How do people respond emotionally to this event? One could easily imagine a certain personality type responding with fear (say, fear of losing their job), while another responds with anger toward those they perceive as responsible for the crisis. Others may feel a mix of these emotions. In these instances, it is important to consider a measure of emotions that distinguishes between anger and fear, which have distinct and often opposite behavioral and attitudinal consequences.

We argue that the structure of the PANAS (and other self-reported emotional scales) encourages survey takers to respond to questions regarding discrete emotions based on their general affect, obscuring differences in discrete emotions. To counteract this, we introduce a modified PANAS that uses a two-step process; this structure primes respondents to more accurately report their emotional state. We use two survey experiments to validate our new measure.

The positive and negative affect schedule

The PANAS is popular primarily because it has long been validated not only by the original creators (Watson, Clark, and Tellegen Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988), but across a variety of research projects designed to measure self-reported emotion (see Brader and Marcus Reference Brader and Marcus2014 for a discussion). Furthermore, it provides a clear and validated set of instructions, straightforward response options, and a multitude of emotional responses in both long and short forms (Watson and Clark Reference Watson and Clark1994).

As illustrated in Figure 1, respondents are given a set of instructions to rate how much they feel a variety of emotions at a given point in time, ranging from “very slightly or not at all” to “extremely” on a five-point scale, a format familiar to researchers and survey respondents alike.

Figure 1 Example of the PANAS.

Challenging the panas

Given the consistent correlations between different negative affective dimensions, both conceptually (Watson and Tellegen Reference Watson and Tellegen1985) and empirically (Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2017; Watson, Clark and Tellegen Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988), we believe that respondents’ arousal of one negative emotion pollutes measures of the others in the standard PANAS. In other words, when presented with a battery of emotions one by one, an angry respondent will report higher levels of anxiety as a manifestation of their general negative affect. This is problematic because it implies that the PANAS (and measures using a similar structure) will suffer from systematic measurement error. While a high correlation between two emotions can cause inflated variances and unstable estimates due to multicollinearity, measurement error of this type can cause even more serious problems by biasing estimates.

These errors and biases make it nearly impossible to correctly attribute associations or causal effects between political outcomes and specific emotions that share generalized negative or positive affect. This is a serious issue because while anger and fear are both considered “negative” or “unpleasant” emotions, they have distinct and often opposing causes and consequences. Anger is provoked when the threat is from a known, specific source, while anxiety is caused by a threat of uncertain source; anger leads to fight, while fear leads to flight (Marcus and MacKuen Reference Mackuen1993). Fear leads to thought, anger to action. Anxious individuals desire information and cognitive engagement, while enraged persons rely heavily on their existing predispositions (Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000).

In some instances, this distinction is not a problem and PANAS can be used. For example, numerous policy areas (e.g., immigration and climate change) can be presented in a way to evoke primarily a fear response (Albertson and Gadarian Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015). In experimental research, well-designed treatments can focus on evoking only anger or fear, and concerns about measurement of these emotions may be somewhat trivial.

In situations where researchers are interested in measuring only generalized affect, the intercorrelations of emotions in the PANAS become a virtue of the scale, rather than a drawback. Since the scale has also been validated for measuring a particular discrete emotion (Watson and Clark Reference Watson and Clark1994), scholars with carefully designed experiments that evoke only a single discrete emotion should find that the PANAS measures perform quite well.

However, in many situations, people do not uniformly feel only anger or anxiety. In these circumstances, which emotion is aroused most will depend on both circumstances and the personality and cognitive appraisals made by individuals – some individuals may respond to a situation with fear, while others respond with anger (Lerner and Keltner Reference Lerner and Keltner2000). These feelings may coexist simultaneously within an individual, who may identify one guilty party (triggering anger) while simultaneously maintaining a generalized sense of uncertain threat (i.e., anxiety) (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Deschenes and Dugas2016). In situations where the most likely emotional response is not clear-cut, we need accurate measurements of these emotions to determine how situations influence emotions, and therefore attitudes and behaviors.

Take the response to terrorist attacks – in the immediate aftermath, individuals may become anxious about the possibility of another attack while also feeling angry that the attack occurred. In addition, individuals can feel a generalized negative affect, distinct from these discrete emotions. If individuals are simply asked the standard PANAS battery, they may have a hard time accurately reporting levels of anger and anxiety in response to this real-world event. While many studies have come up with careful and thoughtful ways to isolate the distinct effects of anger and anxiety in response to this threat (see Huddy and Feldman Reference Huddy and Feldman2011 for a review), it remains difficult to examine how these emotions may operate simultaneously.

This leads to a trade-off that scholars may be loath to make. They can isolate the effects of anger and anxiety individually by designing carefully crafted experiments to evoke only a particular emotion and gain high levels of internal validity, but this can mean missing out on the complicated interplay between these two emotions in response to real-world crises. While there are important theoretical reasons for isolating distinct emotional responses, the political world is not always so clean, and we believe there is added value in the study of more realistic, and less clear-cut, experimental treatments where multiple emotions may be evoked at once. We argue that incautious application of the PANAS for discrete emotional measurement has resulted in biased measures, inflated variances, and unstable estimates when used in associational analysis (e.g., linear regression).

In addition, there are several other methodological concerns with measuring emotions via self-reports, chief among them the concept of “straightlining,” which occurs when individuals give an identical (or nearly identical) response to all questions within a set of responses (Herzog and Bachman Reference Herzog and Bachman1981). Individuals may engage in responses to optimize their efficiency in completing a survey, choosing answers that they find satisfactory, rather than the most precise and honest answer (Krosnick Reference Krosnick1991). Key for our purposes, straightlining can lead to increased correlations between items within a battery and suppress key differences between each concept (Yan Reference Yan and Lavrakas2008).

While straightlining may not occur in emotional inventories at the same level it may in attitudinal inventories where individuals may feel they are giving the same opinion to multiple different questions, the issue of generalized negative affect may cause this problem. Since the PANAS was originally developed to measure generalized affect (Watson, Clark, and Tellegen Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988), it is possible that, in a simple response task, generalized affect could overwhelm more subtle emotions and lead to straightlining behavior. This generalized negative affect may not happen in all cases, especially when treatments are designed to evoke a particular emotional response. However, this may be especially likely in situations where emotional response is less predictable, such as in response to real-world events. In that case, individuals may feel generally bad but struggle to attribute that to a particular emotion, which could increase straightlining behavior in emotional responses.

While one could exclude all respondents who answer the same for each emotional response to avoid the straightlining problem, this solution leads to several other issues. First, researchers are unable to distinguish between someone who genuinely feels high levels of both anger and fear, and someone engaging in straightlining. Furthermore, in experiments, this would amount to conditioning on a post-treatment variable, which can bias estimates of effects (Montgomery, Nyhan, and Torres Reference Montgomery, Nyhan and Torres2018). This becomes especially problematic in a control group, where no emotion is intended to be induced. Is an individual who experiences no anger or anxiety in a control group evidence of straightlining, or evidence that the control was effective in not inducing emotions? Given the response structure of typical self-reported emotions questions, straightlining may indeed be an important problem, and one with no obvious solution.

The issues discussed here are both methodological and theoretical. We do not offer, and likely cannot offer, a solution to the theoretical problems with generalized negative affect. The correlations between anger and fear are generally nontrivial (see Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2017), and a dimension of negative affect is theoretically predicted (Watson and Tellegen Reference Watson and Tellegen1985). However, we believe theoretical issues are not the only issues with disentangling anger and fear. Numerous scholars have created experimental treatments that encourage greater responses of anger and fear (see Brader and Marcus Reference Brader and Marcus2014), and given that these are conceptually different emotions, the correlations between the two should logically be lower than they are using the traditional PANAS. The PANAS provides a simple task for respondents to report emotion, but that simple task may encourage straightlining behavior or simply fail to encourage respondents to think deeply and precisely about their emotional states, leading them to respond to questions based on general affect rather than the arousal of specific, discrete emotions. To this end, we offer a (partial) solution to the measurement problems the PANAS poses.

Solutions to problems with the PANAS

Several approaches have been developed to overcome these issues. One solution to the problem is to use measures that are not self-reported. These measures include autonomic nervous system measures, brain activity (measured with electroencephalograms or functional magnetic resonance imaging), vocal traits, and facial muscle movement (see Mauss and Robinson Reference Mauss and Robinson2009). These measures tend to perform well but have serious drawbacks for researchers. They require both hardware and software to perform, limiting their use to a laboratory setting. For researchers who wish to generalize their work to a larger population, or measure emotions within surveys or survey experiments, and for researchers on limited budgets, these solutions are not feasible. Furthermore, physiological measures may not totally capture the true experience of emotions. Individuals often regulate their emotional responses, and physiological response tendencies often occur prior to any conscious emotional responses (Gross Reference Gross1998). Given that we are particularly interested in negative emotions, which individuals tend to take steps to decrease (Gross Reference Gross2009), physiological response may not totally capture the true conscious experience of emotions.

Measuring emotions in surveys is an important methodological tool for researchers, since even in experiments designed to invoke certain emotions we need to ensure that the correct emotions were indeed activated, and there are many scenarios where laboratory testing is not feasible. Promisingly, research suggests that self-reported emotions at the time of the emotion are considerably more reliable than reflective self-reports (Robinson and Clore Reference Robinson and Clore2002). As self-reports remain a viable, and perhaps the only, measure for most researchers, it is not surprising that others have crafted alternatives to the PANAS.

The Discrete Emotions Questionnaire (DEQ) provides a seven, rather than five, point response scale and provides a larger set of emotional responses with words more easily understood by lay persons (Harmon-Jones, Bastian, and Harmon-Jones Reference Harmon-Jones, Bastian and Harmon-Jones2016). While the DEQ works to better identify discrete emotional responses than the PANAS, it was validated and tested with studies used to evoke only one particular discrete emotion at a time and retains moderately strong correlations between negative affective elements (Harmon-Jones, Bastian, and Harmon-Jones Reference Harmon-Jones, Bastian and Harmon-Jones2016). An alternative measure of self-reported emotion within political science – using sliders instead of radio button responses to the standard PANAS questions – has proven to be more reliable (Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2017). This format exhibits strong construct validity, showing that measures of anxiety and aversion predict what we expect them to. This effort also reduces the correlation between aversion and anxiety from .74 to .61, but the correlation of the two measures remains high (Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2017). The Geneva Emotional Wheel (GEW) provides perhaps the most similar methodological approach to our own, providing respondents a wheel of emotions, varying on both valence and level of control, where they rate the intensity of each emotion (Scheer Reference Scheer2005). The GEW can add cognitive complexity, since it is a relatively unfamiliar task, but it remains a single-step task, where both presence and intensity of emotions are rated simultaneously. Additionally, due to the structure of the wheel, similar emotions tend to be grouped together (Scheer Reference Scheer2005), perhaps increasing the likelihood of straightlining behavior. These have been valuable advances for researchers across a host of areas, especially those trying to measure particular discrete emotions in ways that reduce measurement error. Yet, they do not directly address the issue of straightlining nor of systematic measurement error due to the contamination of discrete emotional responses by general negative affect.

A new approach: the PANAS-M

Although all of these approaches have merit, none explicitly confronts the issue of straightlining. In addition, all use the same sequential rating of emotions tactics that the PANAS uses and therefore are subject to the issue of contamination we mentioned earlier. To deal with these specific issues, we propose a two-step survey response task, which we refer to as the PANAS, modified (PANAS-M). For this scale, participants first must pick any emotions from a list that they are currently feeling. At this stage, respondents simply select if they feel the emotion or not; there is no measure of severity. Any emotion not selected is coded at 0, the lowest level of the scale. Once respondents have selected a set of emotions, they are asked to rate the intensity of all the selected emotions, one at a time, on a scale of 1–5, as with the standard PANAS.Footnote 2 The initial decision task of the PANAS-M is presented in Figure 2. After answering this question, participants then rate the intensity of each emotion one at a time, presented in random order.

Figure 2 Example of the PANAS-M.

Our approach should lead to more accurate reports of discrete emotional responses in several ways. It should minimize straightlining by forcing respondents into different sets of response choices to measure their emotions.Footnote 3 More importantly, it should also serve to make the task more cognitively difficult. Forcing individuals to think in greater depth about a topic causes them to produce responses that are more complex (Barker and Hansen Reference Barker and Hansen2005; Zaller and Feldman Reference Zaller and Feldman1992). More effortful processing of information, as required by this two-step task, can lead to better decision-making (Petty and Cacioppo Reference Petty and Cacioppo1981) that is slower and more logical (Kahneman Reference Kahneman2011), which may give us higher quality, and more accurate, self-reports of emotion. A more effortful response task should cause individuals to make a more detailed reflection before providing a survey response (Forgas Reference Forgas1995). Finally, the structure of the new measure encourages respondents to think first and foremost of discrete emotions, rather than their level of emotional arousal. This should minimize the polluting effect of general negative affect when respondents do rate the severity of their feelings.

While the DEQ (Harmon-Jones, Bastian and Harmon-Jones Reference Harmon-Jones, Bastian and Harmon-Jones2016) provides advances over the original PANAS inventory, and a wider range of emotional responses, it retains a single-step process of reporting emotion. As such, the DEQ remains a relatively cognitively simple task. By providing a two-step emotional response task, we add cognitive difficulty to the task of reporting emotions. Our procedure is flexible and would allow for the valuable contributions of the DEQ, such as creating new emotional questions to evaluate different emotional responses, to be adapted to this measurement framework.

Evaluating the PANAS-M

To evaluate this new scale, we conducted two survey experiments using Mechanical Turk (MTurk). The sample showed demographic patterns typical of online panels (i.e., skewed male, liberal, educated, and young; see the Supplementary Material for details).

We split each sample into half, giving the first half the standard PANAS battery (PANAS-S). We gave the second half the two-step battery, the PANAS-M. We then used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) techniques to estimate factor scores for anger and fear for each respondent. In each sample, self-reported measures of anger and hostility loaded on a latent anger factor; self-reports of anxious and afraid loaded on a fear/anxiety factor; and self-reports of upset, disturbed, and distressed loaded on a negative affect factor. We included the latter to remove some of the polluting effect of generalized negative affect from the discrete emotions of interest. We estimated different CFAs,Footnote 4 with different predicted factor scores, for the following subsamples:

-

1. The pooled sample (including both PANAS versions) for each study

-

2. Those who got the PANAS standard version (PANAS-S)

-

3. Those who got our PANAS modified version (PANAS-M).

Figure 3 presents the correlations between anger and fear for each of these subsamples, with confidence intervals.

Figure 3 Correlations between Anger and Fear by Subpopulation.

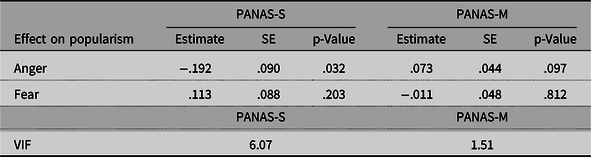

The results are unambiguous: the correlation between anger and fear was substantially reduced using the PANAS-M in both studies.Footnote 5 We see the practical influence of this on analytical results by conducting a simple regression analysis. We regressed a measure of a dimension of populism,Footnote 6 which might be called “popularism” (a belief in the inherent goodness and superior judgment of ordinary people over elites), on both anger and fear and then obtained the variance inflation factors (VIFs). Results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Variance Inflation Factors for Anger and Fear in Regression on Popularism by PANAS Version

Several aspects of this analysis bear commenting on. For one, the correlation between anger and fear for the PANAS-S has serious consequences for interpreting the results of analysis: the VIF for PANAS-S is far higher than the cutoff of 5 that many scholars view as problematic (Stine Reference Stine1995). The VIF for the PANAS-M variables, moreover, is much lower. The instability of the regression estimates’ signs is also a cause for serious concern. Theory predicts that popularism, which is an active, “doing” attitude involving challenging the elite to restore power to the people (to whom it rightfully belongs), should be more correlated with an aggressive, active emotion like anger than an enervating emotion like fear (redacted for anonymity). Here, anger shows a negative effect on popularism when using PANAS-S, contrary to theoretical expectations, but a positive effect (as theory would predict) for PANAS-M. Even the bivariate correlations between anger and fear were unstable; when measured using the PANAS-S, the correlations were both negative, while they were positive when using the PANAS-M, and signed differently when including both emotions in a regression.Footnote 7 This shows that the close correlation between anger and fear, when combined with their diametrically opposed behavioral and attitudinal consequences, can lead to far worse consequences than false negatives and inflated standard errors.

That said, we cannot simply record these correlations and walk away confident in a job well done. It may be that anger and fear simply are highly correlated, and that our tactics artificially reduce that correlation. Additionally, the fact that correlations for the PANAS-M are lower than those for the PANAS-S does not, in and of itself, demonstrate that its measures are less influenced by systematic measurement error.

In short, we need to validate our new measures of anger and fear. We do so by demonstrating that they react in theoretically explicable ways more consistently than do the typical measures. Study 2 was designed to perform this validation. This study included two treatments using videos with priming text to simulate exposure to an economic crisis. Each video is identical except for text placards displayed at the beginning: the videos portray a family devastated by the 2008 financial crisis. The family discusses the loss of their home, their need to take clothes from a charitable bin, and the like. The text placards were intended to provoke different discrete responses. The first (fear/anxiety) emphasized the inevitability of future crises and the inability of governments to prevent such rises; the second (anger) deemphasized future threat and instead encouraged participants to ruminate on the actors whose bad behavior caused the crisis in the first place.Footnote 8

If our modified PANAS (PANAS-M) measures are valid (or at least as valid as the PANAS-S), then we would expect the anger and fear treatments to have effects on the modified measures that are at least as powerful and precise than the standard measures. To test this, we used a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework, which allows us to compare separate samples’ regression coefficients in split samples using group analysis. We regressed anger and fear simultaneously on the three-treatment (control, anger, and fear) model. We then conducted Wald tests to determine if:

-

1. The anger treatments provoked disproportionately more anger than fear for the PANAS-M than for the PANAS-S.

-

2. The fear treatments provoked disproportionately more fear than anger for the PANAS-M than for the PANAS-S measures.

-

3. The difference in (a) anger and (b) fear provoked by the anger and fear treatments is larger for the PANAS-M than for the PANAS-S.

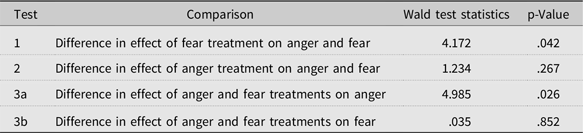

The results of this group analyses, and the results of these Wald tests, are presented in Table 2.Footnote 9

Table 2 Split-Sample SEM Regression by PANAS Version

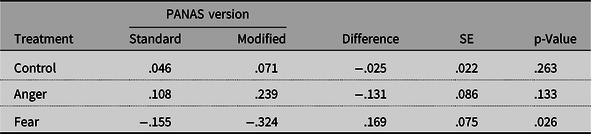

NOTE: As multigroup SEM is not a familiar technique for many social scientists, we also performed a series of t-tests comparing the influence of treatments on the difference of anger and fear by PANAS version. Results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3 T-tests of Difference between Anger and Fear by PANAS Version and Treatment

NOTE: Table 3 presents difference of means t-tests between the standard and modified versions of the PANAS.

These results support the validity of the PANAS-M or at least show that our measures are no less valid than those obtained using the PANAS-S. First, it should be noted that the PANAS-S detected significantly higher levels of emotional response across the board than our PANAS-M. While this would seem to support use of the PANAS-S, the incredibly strong correlation between anger and fear when using the PANAS-S suggests that this increased detection is an artifact of respondents’ tendency to simply mark all negative emotions when using this version of the scale; in other words, increased emotional intensity is likely due to contamination by general negative affect in the PANAS-S, which is exactly what our measure is designed to minimize. When it comes to discrete emotions, the PANAS-M is clearly preferable to the PANAS-S. It performs at least as the PANAS-S on all metrics, and on a few it performs better. The fear treatment had a disproportionately strong effect on fear when compared to its effect on anger when using the PANAS-M, compared to the PANAS-S (Test 1). When comparing the effect of the treatments on anger, the anger treatment had a more disproportionately large effect on anger for the PANAS-M measures than for the PANAS-S (Test 3a).

Conclusion

Correlation between anger and fear is a manageable problem; as long as both variables are included in a model, the effects of treatments can be accurately estimated. The fact that a treatment produces both, even in equal proportions, is not an insurmountable hurdle to the goal of isolating the effect of discrete emotions. However, this only holds if the correlation is modest; when the correlation is as high as it is when using the PANAS-S, the level of multicollinearity produces inflated variances and unstable parameter estimates. An even greater concern is that the standard one-step methods encourage respondents to repeatedly express their negative affect on measures of emotions they may not actually feel, or may feel only weakly. In other words, the PANAS-S appears to have intolerable correlations between emotions of the same affective valence and levels of systematic measurement error, which makes it difficult for any analytical technique to properly apportion the effect of anger and fear. The PANAS-M avoids this, and the results in Table 2 demonstrate clearly that these measures accurately reflect respondents’ real emotional states at least as well as the much more highly correlated PANAS-S. As an added benefit, the two-step structure we encode in the PANAS-M discourages straightlining, while encouraging respondents to think about their emotional state in more complexity and to consider more carefully the distinction between emotions of similar affect valence.

By providing an experimental approach to testing the benefits of the PANAS-M, compared to the PANAS-S, we are able to provide significant validation to the value of our scale. Construct validation tends to be weak in social science methodology, with a majority of studies only reporting an alpha coefficient as a measure of validity of latent scales (Flake, Pek, and Hehman Reference Flake, Pek and Hehman2017). By directly comparing our measure with an existing measure, randomly assigned within the same study, we are able to better benchmark the benefits of this approach compared to a traditional approach. This can provide direct evidence that the PANAS-M is an improved measure over the PANAS-S.

While scholars of emotions in politics have developed strong and compelling ways to evoke single emotions, we know relatively little about what happens when emotions co-occur. By presenting a way to measure emotions that reduces the correlation of emotional self-reports, we open an avenue for scholars to conduct experiments with treatments that evoke both anger and fear, allowing them to isolate the effects of these emotions. These treatments can be more similar to real-world events and reactions, adding the potential for increased external validity to complement existing, internally valid studies of single emotions. We also provide additional evidence that individuals can discern between these two emotions in self-reports, showing that individuals respond with appropriate emotions to stimuli using our measure, and that it performs as well or better than the PANAS-S in capturing these emotions.

As with all survey experimental studies, especially those using convenience samples, attention should be paid to concerns about external validity. Perhaps minimizing external validity concerns is that MTurk workers are more attentive to instructions than the general population (Hauser and Schwarz Reference Hauser and Schwarz2016). Attentive respondents should pay more attention to the videos in the anger and fear treatments and should subsequently be more likely to respond in theoretically expected ways. The PANAS-M makes this distinction well, but the PANAS-S provides problematically high correlations. However, MTurk workers also learn from their experience (Chandler et al. Reference Chandler, Mueller and Paolacci2014); it is reasonable to expect, given the prevalence of the PANAS-S measures of emotion, that workers are familiar with these measures. This may make them more likely than a standard respondent to engage in straightlining behavior, which would inflate the correlations seen in the PANAS-S and deflate correlations in the unfamiliar PANAS-M, solely due to the novelty of the measure. It is possible then that on MTurk, the difference in correlations between the two forms of the PANAS is larger than it would be in a more naïve subject pool.

While we should consider how different subject pools may respond differently to different measures, given that MTurk is a highly prevalent subject pool in the social sciences, understanding how MTurk workers respond to differences in question type when measuring their emotions is vital. The two-step structure of the question should make the task more cognitively difficult for MTurk workers, which should therefore reduce concerns about straightlining, even as the measure becomes more familiar. This logic of a two-step structure should also be applicable to other self-reported scales, such as the DEQ, and other online panel samples that reply to multiple surveys. The result is that analyses of mixed emotional states will be more valid and less plagued by bias and measurement error.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2019.35.