Honesty has long been regarded as a trait that citizens value in political candidates and leaders (e.g. Bishin, Stevens, and Wilson Reference Bishin, Stevens and Wilson2006; Funk Reference Funk1999; Kinder et al. Reference Kinder, Peters, Abelson and Fiske1980). And yet, political statements cannot always be easily dichotomized as either fact or fiction; politicians frequently say things that are somewhere between a complete truth and a blatant lie. Moreover, even when statements are shown to be false, politicians often stand by their claims and employ a variety of tactics to avoid admissions of dishonesty, such as introducing critical qualifiersFootnote 1 or claiming accidental misphrasing.Footnote 2 Thus, a great deal of political communication is perhaps better defined in terms of truthiness, a concept coined by comedian Stephen Colbert to refer to “truth that comes from the gut, not books” (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Garry, Bernstein, Kantner and Lindsay2012, p. 969). But while truthiness has become ubiquitous in US politics, Footnote 3 the political science literature has yet to explore how citizens evaluate leaders when they make these types of factually dubious claims. That is, while a number of works (e.g. Basinger Reference Basinger2013; Doherty, Dowling, and Miller Reference Doherty, Dowling and Miller2011, Reference Doherty, Dowling and Miller2014; Eggers, Vivyan, and Wagner Reference Eggers, Vivyan and Wagner2018) have examined how citizens respond to news of a candidate’s involvement in some type of scandalous behavior that implies or involves dishonesty or deception (e.g. the misappropriation of funds; an extramarital affair), none have explicitly looked at reactions to instances where the potentially scandalous act is simply the candidate’s rhetoric itself. As such, we explore whether and how statements that are not necessarily supported by facts impact citizens’ evaluations of candidates.

Specifically, we explore why an electorate that seemingly values honesty continues to nominate and support candidates who stray from the truth. We hypothesize that this occurs because the consequences of truthiness are contingent on biases stemming from the candidate’s sex and shared party affiliation. After elaborating on our expectations, our original experimental results show that there is a significant decrease in positive trait evaluations when the candidate is presented as a woman versus as a man. Those from the same party, however, are less likely to believe that the female candidate lied on purpose and became more likely to support her. In total, these findings make important contributions to the studies of campaign communication and political scandals, as they demonstrate that while some types of political missteps may lead to more universally negative repercussions, reactions to truthiness or “misspeaking” are more complex and shaped by significant biases.

Hypotheses

Our expectation that there will be differences due to the candidate’s sex is rooted in the premise that women are generally regarded as more honest than men. This proposition is supported by economic research that repeatedly shows that women are more likely to be trusted than men (e.g. Beck, Behr, and Guettler Reference Beck, Behr and Guettler2013; Buchan, Croson, and Solnick Reference Buchan, Croson and Solnick2008; Kosfeld et al. Reference Kosfeld, Heinrichs, Zak, Fischbacher and Fehr2005), as well as political science findings that (1) female candidates are more likely to be stereotyped as honest (e.g. Dolan Reference Dolan2018); (2) voters are less likely to believe in fraud from female candidates (Barnes and Beaulieu Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2014); and (3) voters who value honesty are more likely to support women (Frederick and Streb Reference Frederick and Streb2008).

When evaluating a candidate after a statement of questionable veracity, the assumption of greater honesty from a female candidate can have two potential effects. For one, it can contribute to a woman receiving harsher penalties than a man. A statement that is not 100% accurate may be viewed as counterstereotypical and a violation of the honesty expectation. And while emphasizing positive counterstereotypes can help a female candidate (Bauer Reference Bauer2017; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993), negative counterstereotypic behavior can trigger significant backlash (Krupnikov and Bauer Reference Krupnikov and Bauer2014). That is, “female politicians have ‘further to fall’ if wrongdoing is revealed: to the extent that female politicians’ support draws more on voters who are attracted to perceived integrity, their support stands to suffer more when a lack of integrity is found” (Eggers, Vivyan, and Wagner Reference Eggers, Vivyan and Wagner2018, p. 322; see also Funk Reference Funk1996).

However, a statement that is not 100% accurate is not necessarily 100% inaccurate, either. Thus, if women are assumed to be less likely to lie, then citizens may be more likely to think the initial claim was not intentional deception. This benefit of the doubt may in turn lessen the backlash that female candidates face. Moreover, other female stereotypes may reduce belief in wrongdoing and increase leniency. For example, Wei and Ran (Reference Wei and Ran2019) argue that the association of women with warmth makes subjects more likely to forgive and trust a corporation for bribery if the spokesperson for the corporation is a woman versus a man. Additionally, Barnes and Beaulieu (Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2018) show that women are less likely to be perceived as engaged in corruption because they are assumed to be more risk averse. As such, women who make questionable statements may actually fare better than men.

Whether or not a female candidate is punished more harshly should be conditional on a second factor: partisanship. We contend that one of the reasons that previous works on trust violations (e.g. Eggers, Vivyan, and Wagner Reference Eggers, Vivyan and Wagner2018; Smith, Smith Powers, and Suarez Reference Smith, Smith Powers and Suarez2005; Stewart et al. Reference Stewart, Rose, Rosales, Rudney, Lehner, Miltich, Snyder and Sadecki2013) fail to consistently find significant sex differences is because they do not consider this heterogeneity. As such, we explicitly account for the differences related to shared versus opposing partisanship. Individuals should only punish a woman for counterstereotypic behavior when they are motivated to do so (Kundra and Sinclair Reference Kundra and Sinclair1999). The animosity that citizens tend to harbor for the outparty (e.g. Abramowitz and Webster Reference Abramowitz and Webster2016) should provide sufficient motivation, and so we advance:

H1: Following a factually dubious claim, female candidates will be penalized more than male candidates when they are from the opposite party of the citizen.

In contrast, citizens from the same party should lack the motivation to punish, as the presumed benefits of having a victorious candidate from one’s own party should reduce the incentives to inflict penalties on any inpartisan candidate (Beaulieu Reference Beaulieu2014). And in the absence of negative partisan motivations, inpartisans should be more likely to default to gender stereotypes that may favor women in these types of questionable instances. Thus, we also expect:

H2: Following a factually dubious claim, inpartisans’ evaluations of female candidates will be equal to or higher than those given to male candidates.

Experimental Design

In summer of 2017, we recruited US subjectsFootnote 4 from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk).Footnote 5 A total of 1,200 subjects completed the study and were paid a flat fee for their participation.Footnote 6 Though a convenience sample, MTurk samples are generally similar to more representative samples on a number of important dimensions (e.g. Clifford, Jewell, and Waggoner Reference Clifford, Jewell and Waggoner2015), and the effects observed in experiments run on MTurkers tend to be similar to those observed among more representative samples (Arechar, Gächter, and Molleman Reference Arechar, Gächter and Molleman2018; Mullinix et al. Reference Mullinix, Leeper, Druckman and Freese2015).

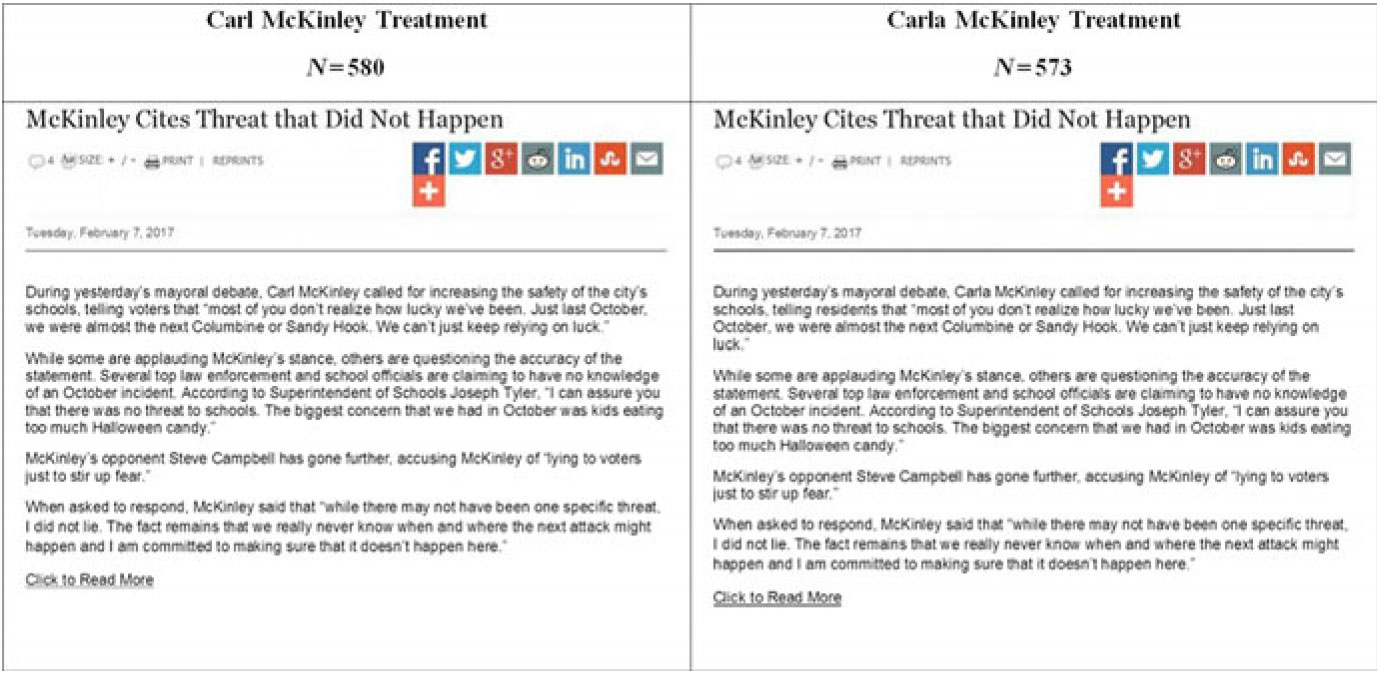

After a brief pretest, all subjects were shown information about what they were told were two candidates for mayor in a mid-sized city in another state. Each of the hypothetical matchups was between Steve Campbell and Carl(a) McKinley. Random assignment determined which candidate was the Democrat or the Republican and whether McKinley was presented as a man (Carl) or a woman (Carla). Figure 1 shows examples of the treatments, which contained a picture and statement from each candidate. Note that the pictures used for Carl and Carla McKinley were selected based on a pretest, which revealed no significant differences in perceptions of attractiveness, age, race, competence, or professionalism.Footnote 7 Overall, this results in a 2 (Democratic or Republican label) x 2 (male or female name and picture) design where the candidate statement was held constant.

Figure 1. Example experimental treatments.

The order in which the candidates were presented was randomized. Following exposure, subjects were asked to use a 5-point scale to rate how well each candidate was described by each of eight words or phrases: likeable, competent, sincere, qualified to by mayor, trustworthy, intelligent, stable, and dependable in a crisis.Footnote 8 Once both candidates were evaluated, subjects were told that they would be asked to express a preference for one of the two candidates, and that they would be given a chance to explain that preference. This method follows Krupnikov, Piston, and Bauer (Reference Krupnikov, Piston and Bauer2016), who show that giving individuals a chance to “save face” leads to more accurate estimates of biases in candidate preferences.

Subjects then proceeded to another, unrelated survey module. Upon completion, all were shown the following prompt:

Think back to the information we showed you about a mayoral race. During the campaign, there was a controversy over some comments made during the candidate debate. Please read the following news coverage of the incident and then answer the questions that follow.

The next screen then displayed the appropriate (based on previous random assignment to the Carl or Carla condition) mock news article shown in Figure 2. This article reported that McKinley referenced a mass shooting threat that never happened. Note that our treatments are unique in that they do not present a clear wrongdoing, but rather, a statement that can be interpreted in several ways.

Figure 2 Treatments reporting McKinley’s questionable statement.

Subjects were then asked to again rate McKinley on the eight traits utilized before. They were also again asked to express a vote preference via the “saving face” method, and to answer four questions more directly related to the information in the article. Lastly, subjects were asked if the shooting threat that McKinley referenced did in fact happen. They then proceeded to the end of the survey, where they were eventually informed that this portion of the survey was fictitious.

Results

We begin with an examination of the trait ratings. In our analyses, we collapse the eight trait ratings down to three dimensions:Footnote 9 integrity (sincere, trustworthy, and likeable; α = 0.87), ability (competence and intelligence; α = 0.86), and performance (qualified to by mayor, stable, and dependable in a crisis; α = 0.89). For each trait dimension, we use ordinary least squares to analyze each subject’s (1) ratings before exposure to the article about McKinley’s questionable statement; (2) ratings after exposure to the article about McKinley’s questionable statement; and (3) change in ratings (2nd rating–1st rating). Each of these dependent variables is modeled as a function of whether the subject was from the same (0) or opposite (1) party as McKinley,Footnote 10 whether McKinley was portrayed as a man (0) or a woman (1), and the interaction of the two. We elect to model shared partisanship in this manner because although some prior works suggest that there may be partisan asymmetries,Footnote 11 analyses presented in Table A5 in the Appendix are instead more consistent with Bauer’s (Reference Bauer2017) findings that both Democratic and Republican respondents are equally likely to penalize a counterstereotypic woman from the opposite party.

As Table 1 shows, the results are consistent across all three trait dimensions. Prior to exposure to the article, subjects from the opposite party of McKinley gave significantly lower ratings, regardless of whether McKinley was portrayed as a man or as a woman. But when looking at the ratings given after exposure to the article about McKinley’s questionable statement in both an absolute sense and relative to the first rating, there are significant interactions between shared partisanship and the candidate’s sex. The relationship between these two factors is better illustrated in Figure 3, which plots how the sex differences impact changes in both in- and outpartisans’ trait ratings.

Table 1 Regression Analyses of McKinley’s Trait Ratings

* =p<0.05; entries are OLS coefficients with standard errors in parentheses.

Figure 3 Effects of the candidate sex treatment on change in evaluations. Estimates derived from models presented in the third column of Table 1. Change is calculated as the 2nd Rating - the 1st Rating. Bars represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3 shows that among those from the opposite party, the post-statement decreases in McKinley’s ratings are significantly greater in magnitude (–1.09 vs. –0.80 for integrity; −1.10 vs. −0.79 for ability; −1.07 vs. −0.80 for performance) when McKinley is presented as a woman versus as a man. Conversely, among those from the same party, there appears to be a slight advantage for the female candidate. Though none of the inpartisan sex differences in Figure 3 are statistically significant, they are all positive, indicating that the decreases in trait ratings that were observed when McKinley was portrayed as a woman were less than those observed when McKinley was portrayed as a man. Moreover, inpartisans’ predicted absolute ratings of McKinley’s integrity (second column of Table 1) are significantly higher when McKinley is a woman (2.52 vs. 2.35, p<0.03). Thus, the trait evaluations are consistent with our theory that outpartisans should possess the motivation penalize the female candidate more harshly than the male candidate, while inpartisans should not.

We next examine overall candidate preference. We use a logistic regression model to analyze post-statement preference for McKinley (1) versus Campbell (0) as a function of opposing partisanship, candidate sex, and the subject’s initial candidate preference. Because this model includes a triple interaction (and all constituent parts), we present the full results in Table A6 in the Appendix and only present the marginal effects of candidate sex in Figure 4 in the main text.

Figure 4 Marginal effect of candidate sex on post-statement preference for McKinley. Estimates derived from model in the Appendix. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

When looking at those from the opposite party, the sex differences are not statistically significant. While this lack of statistical significance differs from our trait results, it is consistent with Goren’s (Reference Goren2007) findings that while citizens are motivated to identify character flaws in even relatively unknown outparty candidates, these motivations only spill over to more global evaluations once the candidate has developed a known record (e.g. a presidential candidate running for reelection vs. running for the first time). And still, the substantive difference should not be ignored; the outpartisan defection rate from McKinley to Campbell was 67% when McKinley was portrayed as a woman, but only 62% when McKinley was portrayed as a man.

Among inpartisans, however, Figure 4 again suggests an advantage for the female candidate. In particular, those who initially preferred Campbell are significantly more likely to express a preference for McKinley after exposure to the article about the questionable statement. This may be related to the above noted tendency of inpartisans to still give higher integrity ratings to the woman even after the questionable statement. But to gain further insight, responses to a number of follow-up questions were examined.Footnote 12

First, though inpartisans’ second integrity ratings were higher when McKinley was a woman, it does not appear that subjects were more likely to believe her. When asked if there was (as McKinley initially stated) a shooting threat to the city’s schools, the percentage of subjects saying yes was approximately equal whether McKinley was portrayed as a woman (8% for inpartisans and 9% for outpartisans) or a man (7% for inpartisans and 10% for outpartisans).Footnote 13 This lack of sex differences is perhaps not surprising, though, given the overall low percentage of subjects choosing the “yes” option.Footnote 14

But while subjects were no more likely to believe a female candidate, inpartisans were significantly less likely to think that the female candidate lied on purpose. Figure 5 plots how candidate sex affected subjects’ agreement with the statement “Candidate McKinley intentionally lied.”Footnote 15 As the left-hand panel shows, subjects from the same party as McKinley were significantly more likely to disagree with the idea that the lie was intentional when McKinley was presented as a woman rather than a man. In contrast, the right-hand panel shows that outpartisan subjects had a slight tendency toward greater agreement when McKinley was presented as a woman, but none of the sex differences depicted in this panel are statistically significant.

Figure 5 Marginal effects of candidate sex on predicted level of agreement with the statement “Candidate McKinley Intentionally Lied”. Estimates derived from an ordinal logistic regression model in the Appendix. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Lastly, Figure 6 shows how the candidate’s sex affected agreement with the statement “Candidate McKinley should not be penalized.” Here we observe significant sex differences among both in- and outpartisans, though in different directions. The left-hand panel shows that inpartisans are significantly less likely to think that the candidate should be punished (i.e., more likely to agree with the statement) when McKinley is portrayed as a woman. Outpartisans, on the other hand, are significantly more likely to think the candidate should be punished (i.e., less likely to agree with the statement) when McKinley is portrayed as a woman. So while outpartisans do not necessarily see the woman as more intentionally dishonest, they still express a desire for her to face consequences for the questionable statement.

Figure 6 Marginal effects of candidate sex on predicted level of agreement with the statement “Candidate McKinley Should Not be Penalized”. Estimates derived from an ordinal logistic regression model in the Appendix. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Altogether, our experimental results imply that the female stereotype of honesty can have both positive and negative effects when a candidate makes a statement that is more “truthy” than truthful. This seemingly counterstereotypical act can lead to lower positive trait evaluations and a greater desire to punish among those from the opposite party. And yet, it may also earn a female candidate the benefit of the doubt from those from the same party. Inpartisans are less likely to think there was an intent to deceive and more likely to rally around the candidate even if they are no more likely to believe her.

Discussion

As the number of women running for political offices continues to rise, it is vital to consider whether or not female candidates are held to the same standards as their male counterparts when making statements of questionable veracity. Our experimental findings suggest that the answer is “no.” Yet whether different equates to better or worse is contingent on shared partisanship. On the more negative side, we see that those from the opposing party possess a significantly greater desire and tendency to punish the female candidate. Though citizens are increasingly loyal to the own party, regardless (e.g. Abramowitz and Webster Reference Abramowitz and Webster2016), negativity stemming from these harsher penalties might further exacerbate election aversion among female potential candidates (Kanthak and Woon Reference Kanthak and Woon2015).

But on the more positive side, we find that among inpartisans, a female candidate may actually enjoy an electoral advantage after a questionable statement. This is notable, especially given that (1) we asked the vote choice questions in a manner shown to depress support for female candidates (Krupnikov, Piston, and Bauer Reference Krupnikov, Piston and Bauer2016); and (2) this substantive result holds true even when we separate our sample by subject sex and partisanship.Footnote 16 This (along with the null vote choice results for outpartisans) also suggests that the gender bias uncovered by Ono and Burden (Reference Ono and Burden2018) may be limited to presidential candidates and not extend to other types of executive office. In sum, then, our findings paint a more positive picture for women in politics than some other previous works.

Of course, there are limitations of our study that require acknowledgement.Footnote 17 First, our subjects were reacting to limited information about an isolated incident. While copartisans may seem more willing to forgive a female for a singular incident, it is unclear whether this would hold over the course of a long campaign or if there were multiple questionable statements. Second, we examined subjects’ immediate reactions. The effects of information about candidate missteps are contingent on both the timing and repetition of the negative information (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2014). Future work should incorporate panel experiments to test whether these two factors operate the same way for both male and female candidates. Third, while our theory is based on the idea that any differences observed are driven by citizens’ reactions to the behavior of the woman, they could instead be a function of beliefs about men. That is, what we refer to as a penalty for being a woman could well be a reward for a being a man. Thus, our propositions about the mechanisms driving our results are still speculative, and a design that includes a non-gendered control is needed to more definitively ascertain which sex is the deviation from the norm. Lastly, we look only at reactions to white candidates. Work on ambiguous rhetoric (Piston et al. Reference Piston, Krupnikov, Milita and Ryan2018) suggests that extending this design to also vary the candidate’s race and/or ethnic background might yield different results. But these limitations do not take away from the value of the present work as much as they reinforce our claim that this is a relatively understudied area that deserves more scholarly attention. Understanding electoral politics in the era of truthiness requires greater insight into which types of candidates stand to win or lose from (mis) stating the facts.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2019.18.