I

Simony, that is to say the illicit purchase or sale of ecclesiastical office, has a long and controverted history within the Church. Most historians would nevertheless agree that mid- and late eleventh-century western Europe constituted an especially important moment in that history.Footnote 1 Accusations of simoniacal practices proliferated, and these accusations were not purely rhetorical. In Italy, France and the Empire, they drove or contributed to the formal deposition of senior clerics: Bishop Hugh of Langres in 1049, Bishop Pietro of Florence in 1068, Bishop Herman of Bamberg in 1075 and Archbishop Manasses of Reims in 1077, to name but a few high-status victims. Indeed, it was the accusation that he had paid for his office that led to the resignation (or deposition) of Pope Gregory vi at the Council of Sutri in December 1046, held at the behest of Emperor Henry iii, who may have spoken there in person on simony's nefarious consequences.Footnote 2 Along with clerical marriage, simony has been regarded as one of the trademark vices of the period: the focus of a ‘moral panic’ for Timothy Reuter, the ‘chief concern of the church reform movement’ for Oliver Münsch and a ‘driving force’ for reform for Rudolf Schieffer.Footnote 3

While it is therefore evident that simony became a pressing issue in eleventh-century western Europe, it remains less clear why. After all the notion itself was hardly new. From late antiquity, the purchase of office had been prohibited within the Church, many centuries before analogous practices were forbidden in secular or state contexts.Footnote 4 It was labelled as simoniacal, in reference to the biblical archetype of Simon Magus, who had tried to buy holy power from the Apostles (Acts viii.18–20). In the sixth century, simoniacal practices were recast by Pope Gregory the Great as not merely sinful but heretical. Gregory coined the phrase simoniaca haeresis in a homily written around 591, and expanded the notion of simony to include, in a famous formulation, the obtaining of the sacred for gifts of the hand, mouth and deference – in other words bribes, flattery and favours.Footnote 5 The scope of what was understood as simony itself did not subsequently greatly change.Footnote 6 Simony was condemned in church councils in the ninth century, and occasionally in the tenth, but apparently without insistence or enthusiasm.Footnote 7 Why then did the issue gather such ferocious energy in the eleventh century?

Perhaps the most common explanation is to point to the growing commercialisation of the wider European economy in the eleventh century, and to suggest that this enmeshed the Church in the cash nexus more deeply than before. The customary exchange of favours that underpinned a society based on patronage took on a different complexion when those favours were converted into cold, hard cash; moreover, it was more immediately comparable with the example of Simon Magus, who had offered the Apostles money. As Megan McLaughlin puts it, ‘The eleventh-century “discourse of simony” drew heavily on a new vocabulary of dirt, defilement, and disgust, which seems to reflect several major cultural shifts occurring around the turn of the century, almost certainly related to the expansion of commerce and the increased circulation of money.’Footnote 8 An alternative approach to the rise of simony is more sociological, linking it to the growing institutional autonomy of the church apparatus. In this reading, simony took on new prominence as a front in the eleventh-century war against the ‘proprietary Church’, that is to say the traditional assertion of influence over clerics by lay church-owners and patrons.Footnote 9 While clerics wanted to keep on receiving gifts from the laity, they preferred not to owe anything in return, and accusations of simony were their means of bringing about this desirable outcome. In Timothy Reuter's words, ‘What the discourse of simony provided was a coded means of renouncing the church's normal gift obligation.’Footnote 10

As R. I. Moore and others have pointed out, these approaches are not mutually exclusive, and commercialisation and church reform can be considered as two sides of the same coin, interacting symptoms of rapid social change. Together they certainly help to account for simony's rising profile.Footnote 11 But there was a further dimension to the simony crisis. For while there was no great change in the concept of simony in the eleventh century, there was a major evolution in its perceived consequences. For the first time it was argued by some that simoniacal ordinations were not only reprehensible but actually invalid.Footnote 12 In other words, if a bishop had bought his office, then he was not merely a bad or sinful bishop: he was no true bishop at all. That in turn meant that the priests whom such a pseudo-bishop ordained over the years had not really become priests, and thus that the sacraments – baptism, the mass, the last rites – dispensed by these pseudo-priests to the faithful were not really sacraments. This argument was elaborated and promoted by influential figures, most famously the Lotharingian monk and Roman cardinal, Humbert of Silva Candida, who wrote a lengthy treatise devoted to the topic, the Three books against the simoniacs.Footnote 13 It had terrifying implications for the whole institution of the Church, with the potential, as Humbert's worried contemporary Peter Damian lamented in 1052, to lead to ‘the overthrow of the Christian religion and to the despair of the faithful everywhere’.Footnote 14

Despite its clear relevance to the question of simony's growing profile, this theological development has in recent years been little studied. That is perhaps because mainstream theology in the Latin West decisively turned against it from the twelfth century, adopting instead a reading of Augustine of Hippo according to which the sacraments of simoniacs are illicit but not technically invalid. That outcome has in turn tempted some historians to dismiss the eleventh-century argument as simply wrong, and so to play down its importance, regardless of the degree of controversy it stirred up at the time.Footnote 15 Its neglect may also be because medieval simony tends today to be studied from a legal rather than a theological point of view.

But the issue has also been neglected because of the received chronology of events. It is generally agreed that the first text to argue clearly that simoniacal ordinations were invalid is a letter now known as the Epistola Widonis, or Letter of Guido, conventionally dated to around 1031 and attributed to an Italian monk named Guido of Arezzo.Footnote 16 This short letter – a mere 600 words – is addressed to someone identified within the text only as ‘your Excellence’.Footnote 17 It begins with a conventional declaration that simony is a heresy, and calls on the recipient to battle against it. After dismissing the argument that wickedly paying for an office can be distinguished from harmlessly paying for the revenues and estates that come with it, the letter states that ‘the masses and prayers of this kind of priest and cleric bring upon the people the wrath of God’, and goes on to say, crucially, that ‘to believe these people to be priests is be entirely mistaken’. In other words, simoniacal priests were not really priests at all. At some point, an extension was added to the letter, which elaborated on the same themes at greater length.Footnote 18

In both its original and its extended forms, the Letter of Guido spread far and wide. It became extremely influential, copied in a score of surviving manuscripts and excerpted in numerous canon law collections, with some passages making their way into the magisterial summary of church law put together by the canon lawyer Gratian in the 1140s.Footnote 19 As a result, the Letter of Guido finds mention at least in passing in most accounts of the eleventh-century Church, and is prominent in discussions of simony.Footnote 20 It is the first work in the great collection of polemic edited in the MGH, Libelli de Lite, series. All this makes its dating and attribution particularly important. Together, they establish the Letter of Guido as the unique piece of evidence that explicit doubts about the validity of simoniacal ordinations emerged in Italy before spreading elsewhere.Footnote 21 And secondly, they chronologically detach the work's apparent theological innovation from the wider social and political crisis of simony which unfolded only from the 1040s onwards.

In short, the conventional dating and attribution of the Letter of Guido underpin a particular interpretation of the simony debates of the eleventh century that suggests they emerged slowly and almost from below in Italy, and gradually built up momentum. But it is often salutary to investigate received wisdom; and in this case, doing so could have significant implications for our wider understanding of the simony crisis. For the dating and authorship of the Letter of Guido are by no means as assured as generally assumed. This article reviews the evidence, and offers an alternative dating and point of origin in the 1060s. It does so as a contribution to a better understanding of what lay behind the emergence of simony as a key discourse within eleventh-century Europe, with significant implications for the nature of the much debated ‘church reform’ of the period, as well as serving as an illustration of how apparently secure knowledge about the Middle Ages can on closer inspection turn out to rest on what seem trivial interpretative cruxes.

II

In most of its medieval manuscript copies, and in most of the medieval references to the text, the letter we call the Letter of Guido is actually attributed to a Pope Paschasius, or sometimes Paschal, and addressed to the Church, people or archbishop of Milan (JL 6613A). On that basis, it would be more accurate to call it the Letter of Pope Paschasius, were it not that this attribution is clearly wrong. There has not yet been a Pope Paschasius, and while the wording, content and transmission of the text make it an impossible fit with Pope Paschal i (†824), some of its manuscripts pre-date the pontificate of Paschal ii (r. 1099–1118).

The now familiar attribution of the letter instead to the Italian monk Guido of Arezzo, and its dating to 1031, reaches back to 1892. In that year Friedrich Thaner provided the still standard edition of the Letter in its original ‘short’ form for the Monumenta Germaniae Historica, bestowed upon the work its modern title of Epistola Widonis and justified his attribution and dating in an accompanying commentary written in dense nineteenth-century Latin. Thaner's arguments can be summed up as follows. First, one near-contemporary author, a south German monk named Bernold of Konstanz (†1100), attributed the text to the monk Guido. Secondly, this attribution can also be found in two manuscripts. Thirdly, Guido was interested in simony and was thus plausible as an author. Finally, there was an event in or around 1031 in Milan which could have provided Guido of Arezzo with a causus scribendi or motivation for writing. Since Thaner's edition, Guido of Arezzo's authorship of the original letter, and its dating to 1031, have been generally (if not quite unanimously) accepted.

Yet despite that wide acceptance, Thaner's arguments are not quite as cast-iron as they have been taken to be. To begin with, his dating of c. 1031 was avowedly tentative, though his nuance has often been forgotten in subsequent work.Footnote 22 In many of the manuscripts, the letter is addressed to Milan or the Milanese; however, in a single, now lost manuscript, the addressee was apparently named as ‘Archbishop Heribert’. It was on this manuscript that Thaner's proposed dating rested. Thaner thought the Heribert it mentions must have been Archbishop Aribert ii of Milan (†1045). That matched what he knew of the dates of Guido's life, and so he looked for an event during Aribert's archiepiscopate that might have provoked the letter. He found it in Aribert's refusal to ordain a bishop of Cremona until he agreed to grant some estates to Aribert's nephew in or around 1031.

Assessed in the round, the argument is not wholly convincing. None of the surviving thirty-one manuscript copies of the letter confirms the lost manuscript's identification of the recipient as Heribert.Footnote 23 Nor do we know anything about this manuscript that would justify privileging it over the rest of the transmission. Its wording is preserved only in a 1678 edition by the Letter's first editor, the French scholar Étienne Baluze.Footnote 24 There, Baluze simply describes the manuscript as one of ‘tria antiqua … exemplaria’ (‘three old copies’), and gave no indication that its version of the text was preferable to any other. While Thaner thought the recipient must have been Aribert ii of Milan, Baluze himself had taken it to be Archbishop Heribert of Cologne (†1021). There is no other supporting evidence to suggest that Archbishop Aribert ii of Milan was suspected or accused of simony during his lifetime.Footnote 25 The text that records the Cremona incident – a later undated charter of Emperor Henry iii – does not refer to it as simoniacal, as Gabriella Rossetti pointed out, and what it tells us does not match the tenor of the Letter, which is firmly aimed at simony in its conventional sense of selling office.Footnote 26 It is true that in 1044 Aribert issued a charter that explicitly required certain clerics to pay six pence on their ordination.Footnote 27 But publicly issuing a charter such as this in itself suggests that this procedure was not seen as problematic in Milan. To rest the dating of the letter entirely on Baluze's mysterious manuscript is thus something of an act of faith.

Meanwhile, the chronology of Guido of Arezzo's life, which Thaner thought supported his supposition, has been thrown into question by Antonio Samaritani. As Samaritani pointed out, there were plenty of Guidos in eleventh-century Italy, and it is not always easy to tell them apart. Guido of Arezzo's activity is thus difficult to date securely. We know from his musical works that he met Abbot Guido of Pomposa who died in 1046, and that he dedicated one of his studies to Bishop Theodald of Arezzo who died in 1036. These dates give us some footholds for dating Guido's activity, but they do not give any indication of when he died. Most historians have assumed that this occurred in the 1030s or perhaps the 1040s, but Samaritani has suggested that Guido remained alive into the 1050s, and indeed that he might have written the Letter as late as the 1070s.Footnote 28 Assuming that Guido of Arezzo was the author of the Letter that now bears his name, therefore, we might have to accept a broader range of possibility for its date.

III

But how assured, in fact, is Thaner's premise that Guido of Arezzo was the letter's author? Guido was a prolific writer, but all his securely identified work is on musical theory: indeed he is still famous in musicological circles for inventing the do-re-mi-fa aural method of musical education. A specialisation in music does not of course preclude a wide range of interests; Regino of Prüm, for instance, wrote about history, canon law and music in the early tenth century. But none of the around seventy surviving manuscripts that preserve Guido's musical treatises contains the Letter of Guido, and nor do any of his works refer to it, even obliquely.Footnote 29 The well-informed monk Sigebert of Gembloux, who knew of Guido's musical work, did not attribute the Epistola Widonis to him in his early twelfth-century catalogue of authors and their works.Footnote 30 A more telling silence is that of the writer Peter Damian, who stayed at Guido of Arezzo's monastery of Pomposa in the early 1040s (and might have overlapped there with Guido), and who composed a long treatise in 1052 known as the Liber Gratissimus on the topic of simoniacal clerics, yet apparently without having heard of Guido's innovative work.Footnote 31

It is also not obvious from what we know of his other surviving work that simony was a major concern for Guido of Arezzo, contrary to Thaner's supposition. If we set the Letter of Guido aside, Guido made just one passing reference to the topic, in a letter to a monk named Michael usually dated to c. 1032. In this letter, Guido reported that his namesake, Abbot Guido of Pomposa, had invited him to return to Pomposa which he had left previously under a cloud, advising him that for a monk, monasteries were better than bishoprics. Guido of Arezzo explained to his correspondent Michael that he had appreciated the abbot's invitation, ‘especially since now that almost all bishops have been damned by the heresy of simony, I fear to enter into communion at all’.Footnote 32 But Guido was not sufficiently concerned actually to accept the offer, since he remained at Arezzo, where he had gone after leaving Pomposa. His comment moreover does not suggest that he viewed simoniacal ordinations as invalid. Indeed, the very fact that he was in contact with Abbot Guido of Pomposa suggests the opposite, given contemporary reports that this abbot had himself been simoniacally ordained.Footnote 33 In short, this statement, isolated amidst an extensive oeuvre, is scarcely sufficient in itself to pin a furious and theologically adventurous criticism of simony upon Guido of Arezzo.

It might be pointed out that Guido did spend a few years at the court of Bishop Theodald of Arezzo (†1036), who has sometimes been described as a doughty campaigner against simony. But the evidence for this bishop's hostility to simony is very late, reported only by Donizo of Canossa, writing around 1110. It is also somewhat ambivalent, given that Donizo says Bishop Theodald wanted to buy the papacy in order to abolish simony.Footnote 34 That this same bishop apparently tolerated a married clerical chancellor suggests furthermore that he might have been more relaxed about adherence to canonical norms than Donizo, writing decades later to burnish Theodald's reputation for a zealous relative, would have us believe.Footnote 35 Finally, there is no evidence that Guido of Arezzo had any interest in or connection to Milan, hundreds of kilometres to the north, and no clue as to why he would have hidden his identity under a made-up papal name, rather than writing under his own name as he usually did. Bearing all this in mind, it is worth scrutinising the reasoning behind Thaner's attribution of the text to Guido more closely, beginning first of all with the manuscripts.

IV

In his edition, Thaner pointed to two manuscripts that appear to name the letter's author as a Guido, although neither specifies that it was Guido ‘the musician’ of Arezzo. One of these is the lost manuscript of Baluze which was discussed above. The other is Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Rome, ms Barb. Lat. 581, a manuscript from the Italian monastery of Monte Amiata. This manuscript is mostly devoted to patristic works by Augustine, Bede and Cassiodorus, but from fo. 242v, there begins a collection of extracts bearing on simony, which opens with the Letter of Guido.Footnote 36 However, Thaner's reading of this manuscript was incorrect. He noted its rubric as ‘Epistola Guidonis monachi contra simoniaca heresi laborentem’, but in reality the manuscript reads ‘Guidoni’, not ‘Guidonis’. This tiny difference is significant because, construed normally, the Latin rubric actually makes the text a ‘letter of a monk to Guido’, not a ‘letter of Guido the monk’.Footnote 37 Of course this might simply be a scribal error; but the manuscript has in any case been dated by Mario Marrocchi to around the year 1100, which makes it a relatively late witness to the text.Footnote 38 Its attribution of the letter to a Guido, if that is what it is, cannot therefore be treated as decisive.

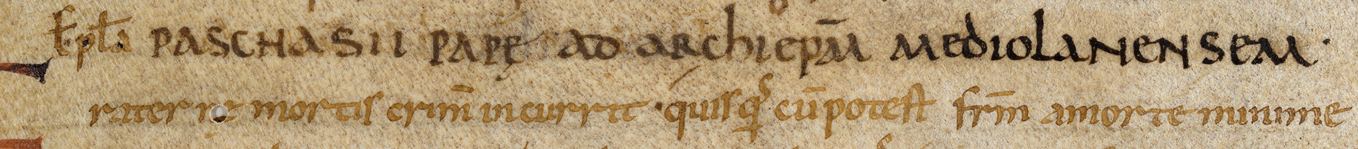

In contrast, the overwhelming majority of the manuscripts attribute the Letter to a Pope Paschasius or Paschal, or else provide no information at all. Take, for instance, a manuscript now in Biblioteca Capitolare Feliniana, Lucca, shelved as ms 124, in which the letter is copied into a separate quire at the beginning of Burchard's Decretum, a well-known canon law collection compiled in the 1020s (fo. 2v). This manuscript is dated to 1050 × 1075, which makes it one of the earliest known copies of the letter.Footnote 39 In this manuscript, the letter carries the heading ‘Epistola Paschasii papae ad archiepiscopum Mediolanensem’ (‘Letter of Pope Paschasius to the Archbishop of Milan’) (see Figure 1). The Letter bears a similar rubric in Biblioteca Laurenziana, Florence, Pluteus XVI, ms 21,Footnote 40 Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, ms 11548,Footnote 41 Stiftsbibliothek, St Gallen, Cod. 676Footnote 42 and Bibliothèque Humaniste, Sélestat, ms 13,Footnote 43 all probably eleventh-century manuscripts.Footnote 44

Figure 1. Biblioteca Capitolare Feliniana, Lucca, ms 124, fo. 2v. Per concessione dell'Archivio Storico Diocesano di Lucca.

A complication is presented by a manuscript now in Bamberg (Staatsbibliothek, Bamberg, Msc.Can. 4, fo. 146v). Here the letter was written by a scribe whom Hartmut Hoffmann called ‘Hand G’, and whose work he dated to ‘the second or the third quarter of the 11th century’, so c. 1025 × 1075.Footnote 45 This is therefore another early copy. The letter has a rubric attributing it to Pope Paschasius, but this was written over an erasure (probably still in the eleventh century, to judge from the script: see Figure 2). What did the original rubric say? In 1861 Paul Hinschius declared that the original read ‘Epistola Widi monachi ad Haribertum archiepiscopum’, or ‘Letter of Wido the monk to Archbishop Heribert’.Footnote 46 That was enough to persuade Friederich Thaner, and probably Henning Hoesch.Footnote 47 However, if this title sounds suspiciously close to Baluze's manuscript, that may be because Hinschius drew on Baluze's edition to guide his interpretation of the palimpsested text. In reality the erasing was done thoroughly, and as noted by one of Hinschius's contemporaries, the Bamberg librarian Hans Fischer, only a few vague letter forms can be deciphered, which are not enough to establish what the original said, even with the assistance of modern technology.Footnote 48 This is frustrating, but there are any number of possibilities for the text's original form, so we should be cautious about speculation.

Figure 2. Staatsbibliothek, Bamberg, Msc.Can 4, fo. 146v: detail of the palimpsested rubric. Reproduced by kind permission of the Staatsbibliothek, Bamberg.

The evidence of most of the manuscripts is reflected in most medieval references to and citations of the Letter, including the earliest, a letter by the German cleric Bernhard of Hildesheim written in 1076, which referred to the Letter's author as Pope Paschal. That was also the attribution provided by Cardinal Deusdedit, who seems to have had access to archives in Rome, in the canon law collection that he compiled in the 1080s, and again in a later polemical work.Footnote 49

In sum, the surviving manuscripts of the so-called Letter of Guido offer conclusive proof for neither the work's author nor its date. The text is too short for a definitive stemma to be produced, as John Gilchrist noted.Footnote 50 In any case, rubrics were among the most readily altered parts of medieval texts, as scribes omitted, edited and occasionally misunderstood what was in front of them. All we can say for sure is that two scribes, one around 1100 and another at an unknown date, associated the letter with a certain Guido, in one possibly as recipient rather than author, and in neither identified as Guido of Arezzo; whereas most eleventh-century scribes and authors thought the letter was by Pope Paschasius or Paschal. Thaner's attribution of the text to Guido therefore rests chiefly on the statement of the south German cleric and monk, Bernold of Konstanz, so it is to this statement that we now must turn.

V

The Letter of Guido was widely cited in the second half of the eleventh century, in Italy but also beyond. In 1076 the southern German cleric Bernold of Konstanz wrote to his former teacher Bernhard, who had moved from Konstanz in Swabia to Hildesheim in Saxony a few years previously, to ask for his opinion on, amongst other things, the validity of simoniacal ordinations.Footnote 51 In his reply, Bernhard of Hildesheim provided the earliest known reference to the Letter of Guido, which he introduced as a letter written by Pope Paschal.Footnote 52 Bernold of Konstanz was not fully convinced by Bernhard's rather convoluted arguments, and told Bernhard as much in a response. However, Bernold did not at this point query Bernhard's ascription of this source to the pope. Indeed, in Bernold's own copies of the Letter of Guido, in Bibliothèque Humaniste, Sélestat, ms 13, fo. 45v–46v, dated by Ian Robinson to before 1076, and in Stiftsbibliothek, St Gallen, Cod. 676, pp. 180–1, written around the same time, the letter appears with the usual title ‘Decree of Pope Paschasius to the Archbishop of Milan’.Footnote 53

A few years later, however, Bernold of Konstanz, having now moved to the monastery of St Blasien, had changed his mind about the Letter. When, between 1084 and 1088, he wrote to his former teacher Bernhard again in a work known as the De sacramentis excommunicatorum, he informed him in passing that the Paschasius letter had actually been written by Guido ‘the musician’.Footnote 54 As Thaner rightly supposed, by Guido the musician Bernold almost certainly meant Guido of Arezzo, whose musical work was widely copied and discussed in southern Germany.Footnote 55 Henceforth this would be how Bernold referred to the text, as for instance in the treatise De statutis ecclesiasticis which he wrote around 1090.Footnote 56 Not only that, but Bernold himself added a curt marginal note to the copy of the Letter of Guido in Stiftsbibliothek, St Gallen, Cod. 676, saying ‘This letter was not by Pope Paschasius because there was no such person.’Footnote 57

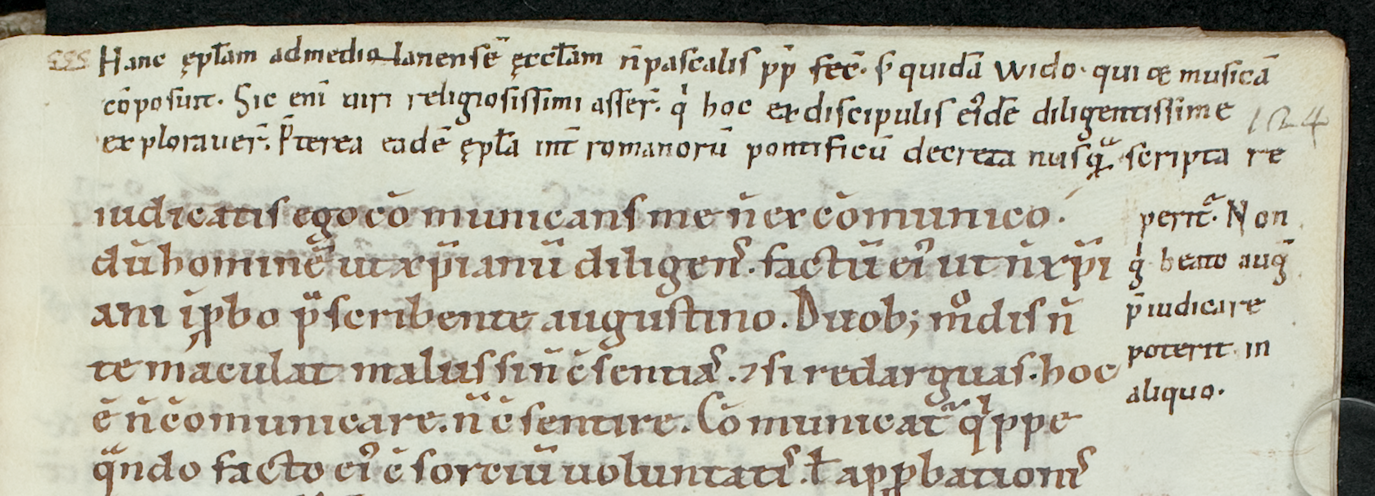

What had happened to change Bernold's mind between 1076 and around 1084? In a marginal note added to a copy of his correspondence with Bernhard, in the eleventh-century manuscript Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart, ms HB VI 107, we find a clue. This gloss, which appears to be a copy of one written by Bernold, states that Bernold had learned that Guido was the Letter's author from ‘most religious men’ who had ‘explored’ this ‘most carefully’ from Guido's own students (see Figure 3).Footnote 58 This gloss is a fascinating reminder of the verbal discussions about texts that are normally lost to us: it is also the peg on which the modern attribution of the text to Guido chiefly hangs. Bernold does not say who these ‘very religious men’ were, nor how he met them, nor how they had met Guido's students, about whom little is known. But one possibility is that he had obtained his new information during a visit to Italy. We know that Bernold attended the 1079 Council of Rome, convened by Pope Gregory vii. There he would have had plenty of opportunity to meet ‘most religious men’, such as Bishop Anselm ii of Lucca, with whom Bernold can be shown to have exchanged texts.Footnote 59 Moreover, we know this was a council that scrutinised textual traditions. Bernold recorded in his chronicle that the council unmasked another text as a forgery, namely a letter which advocated for marriage for priests, and which may have been attributed to Odalric of Augsburg to weaken its force.Footnote 60 Whatever Bernold's sources, we should note that all datable assignations of the text to Guido (including the uncertain attribution in the Vatican manuscript discussed above) post-date Bernold's volte-face, and may have been influenced by him or by his sources; the same could be true of Baluze's manuscript.Footnote 61 The Letter of Guido became the Letter of Guido only after 1076.

Figure 3. Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart, HB VI 107, fo. 124r. Reproduced by kind permission of the Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart.

Bernold of Konstanz was an important and well-connected individual, whose testimony cannot be ignored; and of course he was plainly right that the Letter cannot have been written by a non-existent ‘Pope Paschasius’.Footnote 62 Yet this does not in itself prove that he and his informants were correct in ascribing the text to Guido of Arezzo. After all, Bernold's testimony explicitly relied on oral chains of communication, with all the room for misunderstanding and error that these could have involved. Even with the best will in the world, it might have been difficult to determine the author of a proliferating pseudonymous text decades later. And in this particular case, there were obvious incentives for its reattribution. Like Peter Damian, and doubtless others too, Bernold was worried by the consequences if simoniacal ordinations were invalid; he was also however deeply respectful of papal authority, as his work makes clear.Footnote 63 His quandary in 1076 had been that he disagreed with the letter's contents, but had not wanted to contradict a pope's decree. If, however, the letter was not by a pope but by Guido ‘the musician’, that meant it was a recent work by a far less authoritative figure. So the Letter's uncompromising message could safely be ignored, in favour of a more pragmatic argument that simoniacal ordinations could be valid provided they were ratified by the Church. As Bernold noted with satisfaction in the margins of the Stuttgart HB VI 107 manuscript, the letter, now that it was attributed to Guido rather than Pope Paschasius, ‘therefore cannot prejudice Saint Augustine in any way’.Footnote 64

It is finally worth noting that while Bernold's own copy of the Letter of Guido was the short, original version (as copied in the St Gallen and Sélestat manuscripts connected to Bernold), the quotation of the letter by Bernhard of Hildesheim to which Bernold took exception, and attributed to Guido in his marginal note in the Stuttgart manuscript, was taken from the letter's extended version.Footnote 65 Strictly speaking, Bernold's assertion about the letter's authorship in this manuscript therefore applies to this extended version, not the letter's ‘original’ short version. Yet John Gilchrist, who in his edition defended Bernold's attribution to Guido in the case of the original letter, peremptorily rejected it in the case of the extension, without explaining why Bernold's assessment could be treated as definitive in one context and dispensable in another.

VI

In that edition of the extended version of the letter, Gilchrist suggested that it had been written in Milan, drawing attention to its resonances with an edict issued by papal legates there in 1067.Footnote 66 However, the original version of the letter has Milanese associations too. Most of the surviving manuscripts claim not only that it was written by Paschasius but also that it was addressed to Milan, or to the Milanese. Moreover, the main body of Bamberg Msc.Can. 4 into which the letter was copied, one of the earliest witnesses to the letter, seems to have been written in Milan around the year 1000.Footnote 67 And a Milanese collection of canon law, although preserved in a twelfth-century manuscript (Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan, ms I 145 inf.), may preserve one of the earliest quotations of the Letter of Guido, if we accept the subtle arguments about its dating put forward by Linda Fowler-Magerl and recently developed by Beate Schilling.Footnote 68

In his edition, Thaner too had connected the original form of the letter to Milan. He suggested on the basis of a lost manuscript that the letter had been directed to Archbishop Aribert ii of Milan, whose long archiepiscopate stretched from 1018 to his death in 1045. But, as we have seen, there is no evidence that Aribert was accused of simony in his lifetime. While some early eleventh-century Tuscan aristocrats had begun to refer to simony in general terms when they established new monastic communities, such references are wholly absent from Milanese documentation, and in general there is surprisingly little contemporary evidence that simony was widely regarded as a serious sin in early eleventh-century Italy, still less that its consequences included the invalidity of ordinations.Footnote 69 According to Peter Damian's Life of the hermit Romuald, probably written in the 1040s, simony was considered by many in Italy to be simply normal practice.Footnote 70 Simony in general, and the rejection of simoniacal ordinations in particular, only became a critical issue in Milan during the archiepiscopate of Aribert's successor, Archbishop Guido (1045–71), and especially during the Pataria uprising or movement, in the course of which long-standing practices were for the first time condemned as simoniacal.Footnote 71

Like the author of the Letter of Guido, the Pataria dissidents did not merely criticise simoniacal priests, but publicly rejected the sacraments that they performed. In a famous sermon reported by the chronicler Arnulf of Milan (writing before 1077), the Pataria's leaders Ariald and Landulf roused the crowd against the Milanese clergy, declaring that ‘If you hope for salvation from the Saviour, beware all of them from now on, venerate none of their offices, for their sacrifices are as dogshit and their churches like the stables of farm animals.’Footnote 72 Later, another Patarene leader, Erlembald, publicly destroyed the consecratory oil (technically, ‘chrism’) that had been prepared by a bishop whose holy capacity he doubted.Footnote 73 This is entirely in line with the theological position adumbrated by the Letter of Guido. The Letter's Milanese associations point, in other words, less to the 1030s, when there is no evidence that simony was an issue, than to the late 1050s and 1060s, when it most definitely was.

However, while these Milanese associations are plain, we should remember that the Pataria's focus on simony seems only to have emerged after its leader Ariald's visit to Rome in 1057.Footnote 74 And although the manuscripts do suggest a Milanese context for the Letter, they could be read as supporting a papal connection too. This is perhaps no surprise, given the support and encouragement that the papacy gave to the Pataria movement. It is possible that the Bamberg manuscript was acquired by a papal legate, Bishop Anselm i of Lucca, on one of his two embassies to Milan in the 1050s.Footnote 75 A pair of manuscripts also suggest that the text may have been circulating in papal circles at an early date. In two closely-connected manuscripts of the well-known Decretum of Bishop Burchard of Worms which spread widely and fast in Italy, the Letter is appended along with Pope Nicholas ii's 1059 decree against simony (JL 4431a), without any indication of its author.Footnote 76 Franz Pelster identified these two manuscripts, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, Clm 4570, and Vatican, BAV, ms Vat. lat. 3809, as witnesses to a ‘Gregorian’ recension of Burchard's canon law collection, in other words a version of the work edited in papal circles; he suggested that the earlier of the two, the Vaticanus, was written in Italy around the mid-eleventh century.Footnote 77 These two additions are not present in what seems to be an earlier version of this Burchard recension, linked to Bishop Adalbero of Würzburg.Footnote 78 Did a redactor find the Letter of Guido already associated with Pope Nicholas ii's decree, and add them to Burchard as a pair?

In discussing the influence of the papacy on the Milanese Pataria, several historians have wondered about the role of Cardinal Humbert of Silva Candida or Moyenmoutier, who had arrived in Rome in the entourage of Pope Leo ix in 1049.Footnote 79 In his Three books against the simoniacs Humbert made arguments about the invalidity of simoniacal ordinations similar to those sketched out in the Letter of Guido. That association led Anton Michel to suggest in 1938 that it was Humbert, not Guido, who was the true author of the Letter of Guido.Footnote 80 The proposal met with much criticism. Hans-Walter Klewitz asked why, if Humbert had written the letter, the manuscripts did not just say so (though he did not explain why that argument would not apply equally to Guido).Footnote 81 More seriously, Michel's use of stylistic comparison to attribute ever more works to Humbert came increasingly into question. In 1970, Henning Hoesch cast doubt on Michel's methodology, both in general and in this particular case, arguing that Humbert knew the Letter but had not written it (Hoesch in fact used the letter to illustrate Italian influence on Humbert).Footnote 82 In his 1981 edition of the extended version of the Letter of Guido, Gilchrist relied on Hoesch's work, and relegated the question of Humbert's authorship to a brief footnote.Footnote 83

What Gilchrist seems not to have known, however, is that the case for Humbert's authorship of the letter had been developed since Michel's suggestion. In her 1972 Princeton doctoral dissertation, Elaine Robison had put the case for Humbert's authorship of the Letter of Guido more precisely and clearly than Michel; and this argument was forcefully restated by Margot Dischner in 1996.Footnote 84 Both these historians identified the Letter’s clear links to Humbert's Three books against the simoniacs, finished around 1058, in argument, in intention and in specific biblical and patristic quotations. These arguments do not need to be rehearsed here in detail; it is enough to say, as Robison puts it, that ‘There are virtually no differences between Pseudo-Guido and the Adversus simoniacos.’Footnote 85 Both Humbert and the letter cite Acts viii.9, in which Simon Magus is condemned. That is hardly surprising; but Humbert and the letter's author also interpret the passage in the same way, emphasising that Peter condemned Simon for thinking that he could possess the gift of God, not for actually being able to. And Humbert and the letter also share references to Ezekiel iii.18, Psalm cv, Romans xiv.23 and Titus iii.10, and refer to Jesus throwing out the merchants from the Temple. They also share patristic references, to the Council of Chalcedon, Prosper of Aquitaine and Gregory the Great's epp. xi.219 and xii.9, quoted via John the Deacon's Life of Gregory. Only one quotation, to Fulgentius (ascribed to Augustine), is present in the letter and not in Humbert's Three books, which are in any case only incompletely preserved.

Impressive though they are, whether these arguments are quite enough to pin the original text on Humbert in person remains uncertain. After all, as Robison herself emphasised, Humbert's work on simony was more influential than is often supposed, probably leading to the papal decrees on simony issued in 1059 and 1060. Humbert was not a lone prophet, but a representative of a point of view. The Letter of Guido might therefore just as well have been written by someone in Humbert's circle, or by someone linked to him, whether at Rome or at a linked site such as John Gualbert's monastery of Vallombrosa near Florence.Footnote 86 Alternatively, and as an explanation for its strange fictitious authorship, we might see the Letter as a piece of deliberately pseudonymous Patarene propaganda, inspired by Rome but devised within the city, projected into the past and voiced by a fictive pope properly if anachronistically respectful of Milanese dignity, created by simply re-labelling a pre-existing text intended for someone else entirely (just what the Milanese Bamberg manuscript perhaps records).Footnote 87 This was precisely the sort of letter that the Pataria's leader Ariald and his supporters would have found helpful in their battles against Archbishop Guido, whose own supporters we know marshalled canon law and apocryphal sources in his defence.Footnote 88 Beate Schilling has recently argued that a fossilised trace of precisely such a pro-Patarene dossier from Milan in the 1060s survives in Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan, ms I 145 inf.Footnote 89 This collection quoted the Epistola Widonis text; perhaps its compilation was the occasion of the letter's (re)attribution to Paschal, if not its composition tout court.

At some point after 1076, it became clear to Bernold of Konstanz and his anonymous informants that Pope Paschasius, or Paschal, cannot have been the author of a widely known and influential letter that bore his name. Their decision instead to attribute the letter to Guido of Arezzo may have inspired the scribe of Baluze's lost manuscript; it has certainly shaped the reading of this letter since it was adopted and canonised by Thaner in his nineteenth-century edition, thereby transforming a medieval interpretation of a text into an established historical fact about that text. Yet the re-attribution could have been deliberately obfuscatory or simply the product of confusion: a confusion with Archbishop Guido of Milan, a plausible recipient of the original letter, or with a different Guido entirely. A case can be made that the letter was instead written in or for a Milanese context in the years around 1060, under the influence of Humbert of Moyenmoutier and his circle. Even if Bernold of Konstanz, and the many historians who have taken their cue from him, were right about the attribution to Guido of Arezzo, that does not justify the conventional dating of the letter to 1031, which could be wrong by decades given what we know, or rather do not know, about Guido's life.

These questions about a pseudonymous Latin letter's precise dating and authorship might seem rather abstruse: what does it matter whether a letter was written twenty years later than usually assumed? The issue is nevertheless very significant. For if the letter were dated to around 1060, there would be no substantial evidence for anxiety about simoniacal ordinations in Italy prior to the Council of Sutri in 1046, when the Emperor Henry iii dramatically forced Pope Gregory vi to resign and imposed Bishop Suidger of Bamberg in his place as Pope Clement ii, the first of a series of transalpine clerics enthroned on the Roman see. Moreover, it would suggest that theology might have played a larger role in stimulating the simony debates than hitherto recognised, in combination with the issues of commercialisation and the ever-nebulous ‘church reform’.

Italy had of course been the scene of Donatist-style debates about irregular clerical ordinations before, in the wake of the famous trial of Pope Formosus at the so-called Cadaver Synod in 897. These debates had been largely settled in the tenth century in favour of the ordinations’ validity.Footnote 90 Following the re-dating of the Letter of Guido proposed by this article, however, the debate was reignited by transalpine clerics such as Leo ix and Humbert, who now tied it to simony, with explosive effect.Footnote 91 In this regard, it may not be coincidence that earlier texts which hint at the invalidity of simoniacal ordinations (though without stating quite as much), such as the De dignitate sacerdotali and a letter of Bishop Fulbert of Chartres, were written north of the Alps.Footnote 92

The earliest indication of this new attitude in post-Sutri Italy would therefore be Pope Clement ii's 1047 synod at Rome, at which the German cleric commanded clerics who had been innocently ordained by simoniacs to undergo a forty-day penance.Footnote 93 This ideological shift was then further articulated by Clement's successor as pope, Bishop Bruno of Toul. Adopting the name Leo ix, Bruno took to re-ordaining simoniacal clerics from 1049, in an experimental policy supported by his transalpine associates though fiercely resisted by some Italian clerics, notably Peter Damian.Footnote 94 We might read the underlying theology that posited the invalidity of simoniacal ordinations – a theology to whose dissemination the Epistola Widonis went on to make a powerful contribution – as an attempted reaffirmation of the charismatic in the face of a growing bureaucratisation of the church apparatus, in which appointments were increasingly viewed as steps in a career;Footnote 95 alternatively, we could see it as the rigorous application of Cyprianic views, long fashionable north of the Alps, to the more commercialised world of northern Italy that the northern reformers encountered: the product of a clash of cultures.Footnote 96 In either case, a redating of the Letter of Guido would give the emergence of the simony ‘moral panic’ a more accelerated chronology, and a stronger theological dimension, than has been hitherto recognised. In this reading, doubts about the validity of simoniacal ordination were not an organic Italian development and did not precede the major controversies by twenty years, but were imported along with the reforming papacy, and catalysed those broader debates.

Our view of the dynamics of the eleventh-century simony crisis, and by extension of the eleventh-century Church more widely, thus depends to a surprising degree upon how far we choose to take at face value a gloss in a Stuttgart manuscript, recording anonymous conversations about a pseudonymous text written some time previously, and how we weigh this testimony against an array of codicological, palaeographical and contextual indications that point in a different direction. Without fresh evidence, the question of the authorship and date of the Letter of Guido is probably impossible to resolve definitively. Nevertheless, it is important to realise how unstable the foundations can be upon which mighty scholarly edifices have been reared; an awareness of the limits of what we know is a valuable kind of knowledge too.