This study investigates the late medieval artistic patronage of the Augustinian friars in the eastern Mediterranean by focusing on the church of San Salvatore in Candia (modern Heraklion), the largest convent in the Augustinian Province of the Holy Land. Candia, a port city founded by Arabs (al-Khandaq), and the capital of Byzantine Crete (Chandax) was acquired by the Venetians during the Fourth Crusade in 1204.Footnote 1 After a brief period of conflict, Venetian rule over the city was established in 1211.Footnote 2 Numerous studies have dealt with Candia's economic importance as a port city, its complicated ethnicity, literacy and urban planning, yet there is still much to discover about the convoluted interaction between the Latin and Greek creeds, and the role of art in this.Footnote 3 The richly-textured ecclesiastical topography of Candia was interwoven with places of worship of different faiths, including the cathedral of St Titus, parish churches, Crusader and mendicant convents of the Latin rite, but also Greek Orthodox monasteries and synagogues.Footnote 4 The three great mendicant orders, the Dominicans, Franciscans and Augustinians, had numerous foundations in the city. Of these, most scholarly attention has been focused on San Francesco, a destroyed but once imposing convent built by the Friars Minor on the highest hill of the city.Footnote 5 Besides its association with an antipope, Alexander v (Petrus de Candia, 1409–10), the Franciscan convent has been especially valuable for scholars due to its surviving library and relic inventories from the fifteenth century, and the finely carved sculptural fragments that remain from the main portal of the church.Footnote 6 In contrast, we know surprisingly little about the second largest mendicant convent of Candia, San Salvatore. The aim of this study is therefore to locate the Augustinian convent in the city's complicated holy topography, and to investigate the Augustinian hermits’ strategies of forging bonds with Latin and Greek patrons through the promotion of their cult of saints and holy icons.

Despite its impressive size and significance, San Salvatore has attracted only modest interest in modern scholarship. The demolition of the building was briefly analysed by Olga Gratziou in an article dealing with the controversial artistic heritage of Venetian architecture in Crete.Footnote 7 More recently, Maria Georgopoulou included it amongst the monasteries constructed in the suburbs of Candia in her monograph Venice's Mediterranean colonies.Footnote 8 The building also received some attention from scholars of the Ottoman era, as it was the largest church in Candia to have been converted into a mosque.Footnote 9 This study presents San Salvatore as the most significant Augustinian foundation in the eastern Mediterranean. Building on archival, written and visual evidence, the first half of this article provides a detailed reconstruction of the church and its altars. The second half focuses on the question of interaction among the mixed Latin-Greek population on Crete through investigating icons, altars and in particular the introduction of the cult of the Augustinian miracle-worker Nicholas of Tolentino (c. 1264–1305). By tying together these threads this study contributes to the larger question of Augustinian expansion in the eastern Mediterranean, one of the most neglected aspects of research on the Augustinians and the mendicant orders in general.Footnote 10

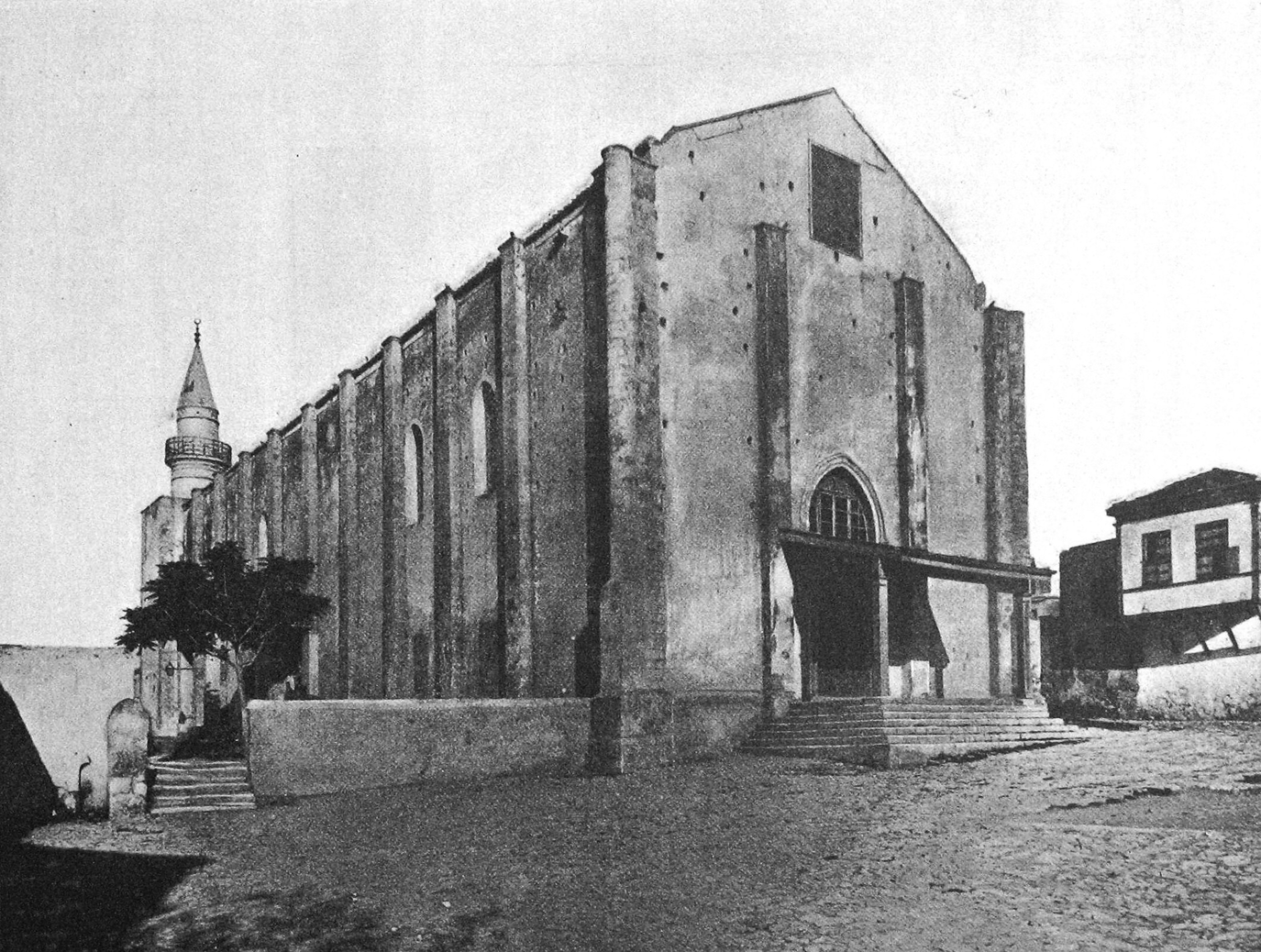

This inquiry also sheds new light on an important yet lost piece of the architectural legacy of Venetian Crete, which was obscured by drastic transformations during the early modern and modern eras. The church of San Salvatore (see Figure 1), which once stood on Kornaros square in the historic centre of modern-day Heraklion, was demolished in July 1970.Footnote 11 By this time the original interior was already heavily altered (see Figure 2). The convent, which would have been close to the church, was lost at some unspecified point in the past. After the Turkish conquest of the city on 27 September 1669, twelve churches were converted to mosques and given to various members of the Ottoman imperial family.Footnote 12 San Salvatore, the largest of them, was chosen to be dedicated to Hatice Turhan, the Valide Sultan (Queen Mother), whose son was Sultan Mehmed iv (1648–87).Footnote 13 As is visible in photographs published by Giuseppe Gerola in his pivotal work of 1908 on Venetian monuments in Crete, a mihrab and conical-capped Ottoman minaret were attached to the building.Footnote 14 The church was purged of its Christian art works and the walls were redecorated with ceramic tiles. The building later housed the city's first female high school. Photographs from around 1970 show that the internal structure was divided into three levels to house the classrooms, and that the surprisingly well-preserved medieval façade was butchered by numerous windows opened in the sidewalls of the former nave.Footnote 15 After an earthquake in the 1960s, the building was abandoned. The residents of Kornaros square requested its demolition in order to allow more sunshine into their apartments. This was agreed by the local authorities who declared it ‘an eyesore in the developing town’.Footnote 16 An eye-witness account of the destruction reported that the bulldozers had difficulty with the massive stone structure.Footnote 17 Today only a rectangular grass patch marks the former position of the medieval Augustinian church in Kornaros square.

Figure 1. External façade of the church of San Salvatore, Heraklion, in 1908: Gerola, I monumenti veneti, 119.

Figure 2. The church of San Salvatore, Heraklion, shortly before its demolition in 1970. © Ephorate of Antiquities in Heraklion.

The eastern mission of the Augustinian Hermits

The Order of the Hermits of St Augustine (OESA, Ordo eremitarum Sancti Augustini) was founded through the amalgamation of various eremitical groups in 1256 as the last major mendicant order, nearly half a century after the Franciscan friars had already begun to organise their eastern province in 1217.Footnote 18 The Friars Minor had founded a convent in Constantinople in 1220, and settled in Candia before or around 1242.Footnote 19 The Dominicans had also established themselves in the eastern Mediterranean by the 1220s, and their Candiot church dedicated to St Peter Martyr became an especially wealthy foundation, which enshrined the tombs of four of the fourteenth-century dukes of Candia.Footnote 20 The Augustinians, therefore, were latecomers to the East, similarly to their situation in their Italian motherland. The first testimony to the establishment of an ‘Overseas Province’ (‘Provincia ultramarina’), headed by a vicar general, comes from the acts of a provincial chapter meeting held in Rome in 1291.Footnote 21 This was mentioned in other documents also as the ‘Province of the Holy Land’ (‘Provincia Terrae Sanctae’) or the Province of Cyprus.Footnote 22 While little is known about which houses the province initially possessed and where they were located, in 1290 the Augustinians bought a convent in Acre from the Friars of the Sack.Footnote 23 This turned out to be a rather ill-timed purchase as the city was captured by the Mamluks in 1291.Footnote 24

Information about the convents belonging to the Province of the Holy Land can be determined with the help of three lists from around 1419 to 1460, 1539 to 1551, and 1659, complemented by the general and provincial chapter acts from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century.Footnote 25 From these, it seems that in the late Middle Ages the Augustinian friars settled in Acre, Corfu (dedicated to St Mary of the Annunciation), Rhodes (St Augustine), Chios, Corone, Chanea (St Mary de Misericordia), Suda-Skopelos (St Mary once referred to as Scoca), Rethymno (St Mary), Mylopotamos (St Mary), Candia (Holy Saviour), Candia (St George, a Benedictine monastery until the mid-sixteenth century), Seteia (St Catherine), Erodiano (St Helias), and in Cypriot convents in Nicosia (St Mary), Famagusta (St Mary), Santa Crux, Silva and Turrim.Footnote 26 This inventory shows that beside Acre, all the known Augustinian houses were founded in Greek-speaking territories, with a concentration on Crete and Cyprus. In contrast to other religious orders, the Hermits established only male friaries.Footnote 27

Augustinian tactics of expansion in the East differed from those adopted for Europe. Some of the most ancient houses of the order were isolated hermitages, which the Augustinian friars maintained even during the late Middle Ages, together with their newer foundations within the city walls.Footnote 28 Not surprisingly, in the eastern Mediterranean the Hermits settled only in the more protected urban areas. Moreover, nearly all of their new convents established in Italy in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were dedicated to St Augustine. This was connected to their increasing ambition to claim the late antique Church Father as their direct founder.Footnote 29 Most Augustinian convents in Greek territories, however, were consecrated to the Virgin Mary.Footnote 30 Such a radical change in church dedication trends is not present in the case of other mendicant groups. For instance, the main Franciscan church in Candia was still dedicated to St Francis, as were many of their other churches scattered throughout Greece.Footnote 31 Francis of Assisi must have been a popular enough saint to attract Greek devotees. This is suggested by numerous wall paintings in Crete from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, for instance in the Orthodox church of Panagia Kera.Footnote 32 On the other hand, St Augustine, as a Latin Church Father, might have seemed to most to be a more obscure Western figure.Footnote 33 As Joan M. Hussey pointed out, St Augustine was not well known even to Greek theologians.Footnote 34 His writings were not available in Greek until the late Middle Ages, and even then only in part. The Marian dedication would therefore have resonated better with local communities. In contrast to monastic orders like the Benedictines or the Cistercians, both of which became extremely successful in medieval Greece, the Augustinians could not rely on landholding and thus had only the local population to rely on to support their convents. Therefore, the change in their church dedication customs suggests that the Augustinians were willing to put aside their pride and show flexibility in order to appeal to a wider audience. But what other techniques and tactics might the friars have employed to compensate for their problematic beginnings? This question will be considered through focusing on the development of the imposing building and sacred space of San Salvatore.

The development of sacred space in San Salvatore

The Augustinian convent in Candia was also not dedicated to St Augustine, but to the Holy Saviour. This title was perhaps inspired by the dedication of the convent of San Salvatore in Lecceto, not far from Siena, which during the thirteenth century became one of the most important centres of the order.Footnote 35

Felix Faber (1441–1502), the famous Dominican pilgrim who departed for the Holy Land in 1483, was impressed by the handsome church of San Salvatore and in particular its masterfully crafted cypress stall.Footnote 36 Johannes van Cootwijck (?–1629), another early modern traveller who ventured to the Holy Land in 1599, described the church as spacious and excellently constructed.Footnote 37 On the basis of archival photographs and the ground plan drawn by Giuseppe Gerola, we can determine that the building consisted of a three-aisled basilica with a square main apse.Footnote 38 Apart from Benigno Van Luijk's unlikely suggestion of 1360, most previous scholars dated the construction of the Augustinian convent to the early fourteenth century with the help of references to the church in wills as early as 1332.Footnote 39 Instead the earliest mention of a church dedicated to the Holy Saviour in Candia appears to be a petition from 17 May 1305.Footnote 40 According to this document, the chamberlains of Crete sought jurisdiction over the church in opposition to the claim of counsellor Hermolaus Georgio who recognised the claim of Leonardo Faliero, the Latin patriarch of Constantinople. While it is not evident whether this refers to the Augustinian convent or its predecessor, either way it demonstrates the existence of the church dedication at the beginning of the fourteenth century. On 30 March 1348 the Hermits received a donation ‘for the building of the new church’, which, as Maria Georgopoulou argued, does not necessarily mean that the construction of the main church building was still in progress, but perhaps only refers to a chapel.Footnote 41 The emphasis here is on calling the church ‘new’. The further decoration of the building continued throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. For instance, six wills from 1362, 1376/7 and 1418 record donations for ‘repair’ and unspecified ‘construction works’ on San Salvatore.Footnote 42 Marchesina Tanto, widow of ser Marcus Tanto, donated ten hyperpera for building works ‘in the church and the convent’ in 1366.Footnote 43 Furthermore, an unpublished will from 1389 states that a chapel was to be constructed by the door close to the campanile.Footnote 44 This is important proof of the existence of the medieval bell tower. Further major renovations took place in 1421, when a contract attests that the friars commissioned a stone staircase outside the dormitory.Footnote 45 When the dormitory cells needed repair in 1431, the document specifically notes their great age.Footnote 46

The surviving sources indicate that various chapels dotted the interior. A church visitation from the time of archbishop Luca Stella (1623–32) in 1625 indicates the existence of nine altars in San Salvatore.Footnote 47 Besides the main altar dedicated to the Holy Saviour of the Transfiguration, on the north side could be found altars dedicated to the Resurrection (St Justina in 1625), St Augustine, St Charles, St Sebastian and, on the south side, to St Nicholas of Tolentino, the Assumption of the Virgin, the Virgin Mary, and the Virgin Mary and St George (‘Zorzi’ in Veneziano).Footnote 48 Some of these were interconnected with other saints’ cults. For instance, a mass for SS Cosmas and Damian had to be celebrated every month at the altar of St Sebastian.Footnote 49 The choir of San Salvatore was originally situated ‘in medio ecclesiae’, and had a stall made of cypress wood decorated with sculpted figures of saints. According to Felix Faber, Jesus, the Virgin Mary, all the Apostles, St Augustine and images of the ‘patron saints of the church’ were represented on the stall.Footnote 50 The choir was moved behind the high altar only in 1616.Footnote 51

The 1625 visitation records numerous paintings in the church. Some of these were probably murals, including the various miracle scenes decorating the chapel of St Charles.Footnote 52 This chapel belonged to a confraternity whose processions are also commemorated in the visitation.Footnote 53 A surviving will of 1350 attests to the commission of further wall paintings in the church.Footnote 54 The main altar was decorated with an altarpiece on which ‘numerous saints were depicted on the same pala’.Footnote 55 Another altarpiece, depicting the passion of Christ, was commissioned for San Salvatore in 1545 from a painter named Zuan Gripioti.Footnote 56

There were also at least two Byzantine icons in the church. In the chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary there was a Marian icon which originated in the Augustinian convent of Rhodes, mentioned as an ‘imagine antica’.Footnote 57 This is described as being surrounded by miracle scenes. This suggests that the picture was a vita icon, a panel painting format distinctive to the eastern Mediterranean and Italy.Footnote 58 Vita icons serve as visual hagiographies: the surrounding scenes show episodes from the life and miracles of saints, for example those of St Nicholas of Bari and St Catherine on two icons from the late twelfth or early thirteenth century from Mt Sinai.Footnote 59 The Virgin Mary on similar icon formats, however, is traditionally surrounded by scenes from her life, passion images, or other saints, instead of miracles.Footnote 60 A rare exception is the icon which was commissioned for a Carmelite church, most likely the one in Nicosia (see Figure 3).Footnote 61 The scenes surrounding the central image depict miracles connected to the Carmelite friars, who appear under the protective mantle of the Virgin of Mercy. The Carmelites, like the Augustinian friars, were rooted in eremitism, but transitioned to a mendicant lifestyle in the thirteenth century.Footnote 62 The commission by the Augustinians of a Madonna icon comparable to the Carmelite example in Nicosia suggests that both mendicant orders developed a similar visual language, which fused Latin and eastern elements. That the Augustinian Madonna icon found its way from Rhodes to Candia is not surprising. A document informs us that due to the Turkish threat treasures from the Augustinian church in Rhodes were sent to San Salvatore for safekeeping in 1520, with the further proviso that if Candia were to be threatened, the treasury should be evacuated to the Augustinian convent of Santo Stefano in Venice.Footnote 63 From these, only one – although exquisite – piece survives: a large, bronze lectern in the shape of an eagle spreading its wings (see Figure 4).Footnote 64 The base of the lectern stands on three tiny lions, and the post is pierced through with a row of pointed-arch windows. The lectern currently stands in the nave of Santo Stefano, the main Augustinian church in Venice, in accordance with the wishes of the Augustinian friars of Rhodes.Footnote 65 The church of San Salvatore in Candia also possessed its own bronze lectern, similarly executed and also resembling an eagle. While it was separately transferred to the convent of Santo Stefano in Venice in 1669, it has subsequently been lost.Footnote 66

Figure 3. ‘Enthroned Virgin with Carmelite friars and scenes of miracles’, before 1287, tempera on panel, 203 cm x 156 cm, Byzantine Museum, Nicosia, BMIAM.006. © Archives of the Byzantine Museum, Nicosia.

Figure 4. Bronze lectern, church of Santo Stefano, Venice. © author.

A second Byzantine icon stood on the altar of the Virgin Mary and St George in San Salvatore, and is described in the church visitation from 1625 as a painting ‘greca et antica di Christo’.Footnote 67 From the report of a seventeenth-century traveller, Wolfgang Stockman, we are further informed that the thaumaturgos icon of the St Titus cathedral, the Madonna Mesopanditissa, was brought to San Salvatore in a procession.Footnote 68 According to Stockman, this procession resulted in a (rather modest) miracle: the sky suddenly became dark and it rained for half an hour.

The ecclesiastical visitation of 1625 describes numerous reliquaries situated above an altar in the sacristy, and a rock-crystal container which probably dates to the medieval period.Footnote 69 While these icons and reliquaries are lost without a trace, the fountain which Zuan Matteo Bembo, the capitano of Candia (1552–4), erected in front of San Salvatore is still standing.Footnote 70 An anonymous chronicle gives a precise description of it:

infinite columns of marble of various colours and likewise a great number of buried marble statues, some large and some small are found there together with fragments of statues of different sorts … and one of these statues without a head or the right hand was placed below the cubit of the fountain of San Salvatore in the city of Candia made by the Illustrious Lord Giovanni Matteo Bembo, who was Capitano of the Kingdom of Candia in the year 1553: these remains and fragments demonstrate that it was a very grand city.Footnote 71

Bembo's fountain combined a headless Roman statue with contemporary Renaissance carvings to create an erudite construction that was able to endorse Venice's claim to antiquity and provide an eye-catching landmark in the square.Footnote 72 As the Augustinians often incorporated spolia in their church interiors to emphasise their claimed antiquity, the construction of the fountain resonated with their own visual language. The fountain also drew attention to the civic function of the space in front of the Augustinian church. A citation from the long-lost but celebrated Description of Crete by Onorio Belli mentioned that ‘in front of the church of San Salvatore in the city of Candia … This is the stone where public announcements are made’.Footnote 73

Icons, saints and liturgy: tactics for attracting devotees

While some donations cannot be connected to specific construction work on the church and the convent, their records help to refine our understanding of the social relations between the Augustinian friars and their lay donors. In the fourteenth century numerous wills attest that women left money to the church in the hope of being buried there.Footnote 74 However, donations made by women were not always monetary. For instance, a widow offered textiles from which she had originally intended to sew clothing to make a paramentum for the Augustinian church.Footnote 75

The question of the friars’ relationship with the local Greek population is also raised by the surviving source material. According to Felix Faber, a vindictive ‘Greek heretic’ once sneaked into the church of San Salvatore and cut off the noses of Jesus, the Virgin Mary, all the Apostles, St Augustine and images of the ‘patron saints of the church’ on the magnificent wooden stall of the choir.Footnote 76 Too much should not be read into Felix's accusation, as other evidence suggests smoother co-existence, and even collaboration between the Latins and Greeks in San Salvatore. While Sally McKee's comprehensive research is cautious about the ethnic markers of the inhabitants of Candia during the fourteenth century, the names of some of the donors betray their Greek origin.Footnote 77 For example, Antonio Greco left five hyperpera to the Augustinian friars of Candia in his will of 1362.Footnote 78

According to Stockman, the procession of the Madonna Mesopanditissa from St Titus to San Salvatore included both Greek and Latin devotees.Footnote 79 There is substantial evidence in Candia for the existence of shared devotional. In the cathedral of St Titus the Greek priests held offices at a Greek altar, which was situated next to an altar dedicated to the Latin rite.Footnote 80 The Latin and Greek clergy celebrated the feasts of Epiphany, All Saints Day and St Titus together in the cathedral, witnessed by crowds of officials, nobles and commoners.Footnote 81 Other churches, for instance Santa Maria de Miraculis, also contained altars that facilitated both rites.Footnote 82 Like San Salvatore, this latter church was situated in the suburbs, where most of the remaining Greek monasteries stood. Their location predestined the friars to engage more ardently with the local Greek community. The surviving evidence indeed suggests that the Augustinians obtained Greek liturgical manuscripts. The prior of the Augustinians bought ‘a psalter written in Greek’ from the Greek Orthodox monastery on Mt Sinai.Footnote 83 This information, combined with the friars’ subsequent interest in the debate over church union, suggests that the Augustinians were able to attract devotees of both rites.Footnote 84 In their other convents in the Province of the Holy Land surviving written sources demonstrate that Greeks wanted to be buried in Augustinian churches. One of the most notable cases is that of Hugh Podocataro, from 1452, who chose to rest in the Augustinian church of Nicosia in the event that he could not be buried in an Orthodox nunnery because he had been married according to the Latin rite.Footnote 85

Hugh Podocataro's altar of choice for his tomb was that of St Nicholas of Tolentino. Nicholas was an Augustinian friar from the Marche in central Italy, whose shrine became an object of devotion and a popular pilgrim destination due to the healing miracles that he performed from the early fourteenth century.Footnote 86 After a first unsuccessful canonisation campaign in 1325, Nicholas was officially acknowledged as a saint in 1446, four years before Hugh drew up his will.Footnote 87 The Augustinian convent in Nicosia acquired Nicholas's relics (three drops of his blood in 1345) and the saint reportedly performed miracles in Cyprus.Footnote 88 Given that he was the only Augustinian friar officially canonised during the medieval period and the order's most well-known saint, it is not surprising that the Hermits were eager to introduce Nicholas's cult to the eastern Mediterranean. An altar was also dedicated to him in San Salvatore. The ecclesiastical visitation of 1625 states that it was founded by Nicolò Tagliapietra.Footnote 89 As the Tagliapietras were one the earliest Venetian families to settle in Candia in 1211, this does not help to determine the date when the altar was endowed, but it does indicate the support of a Venetian patriarch for the Augustinians’ ambition to plant their saint's cult in Candia.Footnote 90 It is also worth considering that the Hermits promoted Nicholas of Tolentino from the beginning of his cult as a ‘new St Nicholas of Bari’. This was also endorsed through visual means, for instance on the murals in the so-called Cappellone, the shrine of Nicholas in Tolentino from around 1320–5.Footnote 91 Here two scenes each depicting the old and the new St Nicholas frame the fresco cycle.Footnote 92 Thus, Nicholas of Tolentino, promoted as the successor of one of the most popular saints both in the East and the West, seems to have been an appropriate choice by the Hermits, one which could have easily resonated with the Italian inhabitants of Candia as well as the Greek Orthodox. Nicholas was a popular saint, called upon for liberation from the plague as well, which struck Candia hard in 1348 and again in 1376.Footnote 93 Finally, he would also have appealed to the citizens of a port city as a saint particularly effective against nautical calamities. This feature was highlighted in his first surviving vita, written by Peter of Monterubiano around 1326, and depicted on another fresco in the Cappellone (see Fig. 5).Footnote 94 Candia's impressive urban, demographic and economic development was rooted in its important role in the Venetian commercial and maritime network.Footnote 95 Sailing was critical for the economic sustenance of the city, which was a major stop-over on the way to the eastern markets, including Antioch and Alexandria.

Figure 5. Workshop of Giovanni di Rimini, ‘St Nicholas of Tolentino saves the people from a storm’, c. 1320–5, wall painting, Cappellone, Tolentino. © Andrea Carloni, Rimini.

Through investigating the surviving archival evidence this study offers a new reconstruction of San Salvatore, the largest Augustinian convent in the Province of the Holy Land. This church carved out an important place for itself in the sacred topography of Candia, not only due to its impressive size which was superseded only by the cathedral and the convent of St Francis, but by its role as an intellectual and monastic centre. The late fourteenth-century liber generalis of the order's prior general Bartolomeo da Venezia shows that numerous provincial chapter meetings were held in Candia.Footnote 96 These functioned as the main internal decision-making body of the Augustinian Hermits, where the delegates of each house congregated to discuss the financial and political affairs of the province, and to elect new officials and their representatives for the general chapter.Footnote 97 San Salvatore also attracted visitors from abroad and, in the permission given to the Augustinian friar Guido da Rimini in 1393 to visit various convents in the Holy Land and Italy, it is listed as a third major site beside the convents in Pavia and Rome.Footnote 98 More locally, the evidence suggests that the learned Augustinian friars of Candia attracted both the Latin and the Greek inhabitants of the city. While the vast library of the Franciscan friars comprised nearly three hundred volumes, it contained only a single book in Greek, a translation of a work by St Gregory the Great, intended for a scholarly audience.Footnote 99 In contrast, the Augustinians acquired a Greek gospel book that had practical liturgical functions. Furthermore, the two ‘antica et graeca’ icons were adept choices to boost prestige, remind viewers of the order's claimed antiquity and to attract Greek devotees. The evidence for a potentially similar vita icon of the Virgin opens up the possibility of placing the Carmelite icon from Nicosia in a new context. It also adds to the collection of prestigious Madonna paintings in Candia, namely the miracle-working Virgin Mesopanditissa in the cathedral of St Titus, the Dominicans’ acheiropoietos Virgin, and the Franciscans’ Virgin attributed to St Luke.Footnote 100 Studying the convent of San Salvatore not only highlights the role of icons, liturgy and the cult of saints in mendicant expansion in the eastern Mediterranean, but sheds new light on the flexibility and resourcefulness shown by the Augustinian friars as they competed in this process.