INTRODUCTION

Japan has been criticized for its failure to adequately come to terms with its wartime history and thereby allay the grievances of its neighboring countries. This is evident when compared to Germany's notable efforts to do so after World War II (Berger Reference Berger2012; He Reference He2009; Lind Reference Lind2008). Indeed, there have been calls in China and South Korea, both former victims, for Japan, the former perpetrator, to follow Germany's example in confronting its colonial and wartime history.Footnote 1 Controversy over Japan's past and its remembrance thereof, its so-called history problem (Rose Reference Rose2005), has become fiercer than ever, often causing Tokyo's relationships with China and South Korea to worsen. In this sense, Japan's history problem has become a significant security issue in East Asia, which could potentially impede peaceful coexistence among the relevant countries (Christiansen Reference Christiansen1999).

This article approaches Japan's history problem in terms of a denial of history (Lind Reference Lind2008, Reference Lind2009; Midford Reference Midford2002).Footnote 2 Specifically, our research question concerns the reasons certain Japanese prime ministers (PMs) have attempted to deny Japan's violent past through highly controversial visits to the Yasukuni Shrine, while other PMs have not done so.

This question is significant in two respects. First, Japanese PMs’ visits to Yasukuni have had an enormous impact on East Asia's international relations. There are three representative aspects of Japan's denial of history: its wartime “comfort women,” the history text issue, and Japanese PMs’ Yasukuni visits. Visits to the Yasukuni Shrine, the symbol of Japanese militarism to many in neighboring Asian countries, are the most contentious and provocative of the three issues. Indeed, such visits give rise to severe condemnation from Asian neighbors as well as domestic criticism from citizens, media, and business lobbyists. The tension caused by such visits stems largely from the nature of the Yasukuni Shrine, which enshrines Class-A war criminals, the top leaders of Japan judged by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East to have committed “crimes against peace.” Therefore, a visit by a Japanese PM to Yasukuni could lead Japan's neighbors to distrust the Japanese government's attitude toward the crimes committed by Class-A war criminals. In that sense, when and why some Japanese PMs choose to visit the war-linked shrine in the first place presents an interesting research question. However, few international relations (IR) scholars have investigated the reasons for the visits as thoroughly as they have examined the effects of the visits (Lind Reference Lind2008).

Second, political leaders’ decisions to pay such visits are puzzling. Paying homage at the Yasukuni Shrine is costly and never easy for Japanese PMs, as described above. Moreover, given the fact that such visits are performed in public and widely covered by the media, Japanese PMs seem to fully understand that negative reactions may be triggered both inside and outside of Japan. Thus, it is puzzling that certain Japanese PMs choose to visit the controversial shrine considering the political cost involved.

To be sure, some previous IR studies have sought to explain PMs’ visits to Yasukuni in terms of their nationalistic ideologies (Ryu Reference Ryu2007; Shibuichi Reference Shibuichi2005) and calculations regarding political survival (Cheung Reference Cheung2010). These previous studies, however, have not successfully explained the empirical pattern regarding which PMs choose to visit the shrine. The limited explanatory power of the existing literature is related to two points. First, the literature has focused exclusively on the benefits of a visit but not on the costs, despite visits being far from cost-free. Second, with regard to the purpose for which political leaders decide to visit Yasukuni, previous studies have tended to consider mainly the domestic effects of a visit rather than the international effects, with a visit most likely to be undertaken to secure political support within Japan. However, we should consider that international actors, as well as members of the domestic constituency, observe such visits, and overseas reactions are closely monitored by Japanese political leaders. Therefore, it might be the case that one of the major purposes of a Japanese PM's visit to Yasukuni is to influence international actors.Footnote 3

Therefore, taking into consideration both the cost and the international effects of Japanese PMs’ visits to the shrine, we propose three necessary conditions for a PM to decide to visit. First, following existing research, a PM's political ideology or the political party to which a leader belongs determines whether that leader visits Yasukuni. Specifically, only conservative party leaders choose to make such visits. Second, given that a visit incurs political costs, leaders choose to visit the shrine only when cabinet popularity is high. Third, and most importantly, we propose that it is only when Japan perceives a security threat from China that a political leader chooses to visit Yasukuni, aiming to show Japan's resolve. Such visits are often associated with assertive and militaristic posturing by Japan and are harshly opposed by past victim countries such as China. This is why we think a Yasukuni visit by a Japanese leader could function as a credible signal of resolve to defend Japanese security against threats from China.

To determine the plausibility of this proposal, we present in this article comparative analyses of Japanese cabinets after the mid-1980s. Most previous literature on Japan's history problem has depended on descriptive case studies; in contrast, we conduct systematic comparative analyses across Japanese cabinets to obtain results that are more reliable.

The next section explains in theoretical terms the three abovementioned causal conditions for Japanese PMs’ visits to Yasukuni and assesses what existing studies have and have not explained adequately. The third section presents an empirical examination of our hypothesis regarding the three conditions. Finally, the fourth section concludes the paper.

WHEN AND WHY DO JAPANESE LEADERS CHOOSE TO VISIT YASUKUNI?

We propose that the decision of a Japanese political leader concerning whether to visit the Yasukuni Shrine depends on three conditions. Two are domestic in nature while the third is international.

DOMESTIC CONDITIONS: POLITICAL IDEOLOGY

The first of the two domestic conditions relates to the political ideology of the government or ruling party. Conservative or right-wing parties generally emphasize the importance of national tradition and patriotism in their political agenda. They are unwilling to acknowledge Japan's wartime history as a blemish on the nation's past, preferring to describe it in glorious terms. In contrast, liberal or left-wing parties tend to express respect for internationalism or universalism, rather than nationalism, in their policies. This ideology is reflected in their sincere desire to come to terms with Japan's wartime history (Lind Reference Lind2008). Therefore, it follows that the governments of conservative parties (but not liberal parties) attempt to deny the negative aspects of their nation's history.Footnote 4

Political ideology on its own, however, is an insufficient reason for a Yasukuni visit. While it is true that a visit might attract and satisfy some members of a particular political party, it is undeniable that political leaders as office seekers would usually place far greater importance on their office and working toward reelection. To this end, they need to gain popular support rather than cling to parochial political ideologies. As long as the visit is intrinsically costly, as explained above, even a nationalistic leader might be constrained in dealing with the past. Therefore, political ideology is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a Yasukuni visit.

DOMESTIC CONDITION: POLITICAL SUPPORT

The most important incentive among incumbent political leaders is reelection to office; therefore, the popularity of a government is a necessary condition for making the risky decision to visit the shrine. Because such a visit would draw harsh criticism from both inside and outside a past perpetrator country, a government or political leader with low popularity would regard it as too risky, as it might further damage his or her popularity and increase the possibility of losing office.

However, popularity does not automatically lead to a Yasukuni visit. A PM who lacks the desire to visit in the first place—such as the leader of a left-wing party—would not visit. High popularity allows but does not drive a PM to visit. Therefore, popularity is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a visit.

The proposition above contrasts with arguments proposed by previous studies that employ the logic of political survival: they claim that Japanese PMs visit the shrine to increase their domestic political support (Cheung Reference Cheung2010; Smith Reference Smith2015). Undoubtedly, numerous influential voters and conservative groups, such as members of the Japan War-Bereaved Families Association (Nippon Izokukai) and the Association of Shinto Shrines (Jinja Honcho), expect their PM to pay homage at Yasukuni Shrine. Indeed, the fact that these two groups have longstanding ties with the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) suggests that a Yasukuni visit by the PM wins votes for the LDP.Footnote 5 However, this explanation is not necessarily accurate, as a visit to the shrine invites some criticism as well as support across the nation and does not always act as a reliable means to maximize political support from the public.

At least two counterarguments can be raised against the logic of political survival described above. First, the number of members of associations such as Nippon Izokukai, which has traditionally urged PMs to visit Yasukuni, has declined since World War II. Therefore, the influence on the ballot of such organizations has diminished. This decrease in the organizations’ numbers and influence would be expected to lead to a decrease in PMs’ incentives to visit the shrine. However, PM visits to the shrine have increased in recent years (Ryu Reference Ryu2007).

Second, business groups, including comprehensive economic organizations with memberships comprising representative Japanese companies, are another important and reliable LDP political support base that does not encourage Yasukuni visits. These organizations rely heavily on international trade with and investment in China; therefore, PMs’ visits to the shrine are frowned upon, as any deterioration of diplomatic relations between Japan and China inevitably hinders business between the two countries. For example, a news article covering a secret meeting between top officials of the Japan Business Federation (Nippon Keidanren) and the Chinese president, Hu Jintao, reported that the meeting suggested “the level of concern Japanese business leaders have over the negative fallout from Koizumi's annual visits to the war-related Shinto shrine” (Japan Times 2005).

Therefore, it is doubtful whether PMs’ Yasukuni visits actually contribute to or can be employed to increase prime ministerial popularity. Rather, it seems likely that high approval ratings are necessary for a political leader to visit Yasukuni because a visit involves the risk of losing a certain amount of political support.

INTERNATIONAL CONDITIONS

We examine here international factors—specifically, Japan's perception of security threats. This article will argue that it is only when Japan, the past perpetrator, regards China,Footnote 6 the past victim, as a security threat that a Japanese leader will decide to visit the shrine as a way of conveying Japan's resolve to stand firm.

Deterrence is one of the most frequently used countermeasures when a country feels threatened by another country: its intention is to prevent the threatening country from changing the status quo by signaling its resolve not to concede. The signal has to be sufficiently credible for the deterrence to be successful (Fearon Reference Fearon1997; Jervis Reference Jervis1970). Our argument is that Japanese leaders choose a Yasukuni visit as a means of such signaling.Footnote 7A Japanese PM's visit to Yasukuni implicitly negates the post-World War II international agreement (Ishida Reference Ishida, Endo and Endo2014). As explained above, the Yasukuni Shrine enshrines Class-A war criminals, and a PM's homage at the shrine implies that Japan does not regret its past war crimes. This naturally leads the previously victimized country to wonder whether Japan would hesitate to use military force against it again. In this way, the visit becomes a deterrent as a signal of resolve toward the past victim country.Footnote 8

Furthermore, it should be noted that a costly visit is a credible signal rather than mere “cheap talk.” Because a visit is so controversial and has been denounced by a number of people, it can damage the administration that performs it. It follows that only an administration or leader ready to withstand the inevitable harsh criticism and resolved to take this risk can visit the shrine. A past victim country can thus distinguish the characteristics of the current cabinet of Japan: either resolved or less so. If and only if the Japanese government is genuinely resolved, will it dare to visit the controversial shrine. Thus, a decision to visit Yasukuni by a Japanese PM sends a credible signal of resolve in the context of a security threat from China, precisely because of the associated political cost and risk, not despite it.

Needless to say, Japan has a range of alternative choices for showing its resolve, such as increasing defense budgets for modernizing or appropriating defensive weapons and strengthening alliances. A visit to Yasukuni is just one possible way to show resolve under a security threat. Thus a security threat is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a visit. Nevertheless, such visits can be important ways to show resolve. First, the visit can be chosen by Japan unilaterally, whereas changing alliance policy requires the agreement of an allied nation. A visit is therefore an important measure, especially when an allied nation's commitment to deter and/or fight against a target country is unreliable. Second, a visit is more suited to sending an immediate and costly signal than defense budget policy. The extent of an increase in defense budget is limited in any given fiscal year, whereas a visit can be conducted immediately. Third, a Yasukuni visit, defense budget policy, and alliance policy are not mutually exclusive. In reality, certain Japanese cabinets, such as the second Abe cabinet, have undertaken all three simultaneously.

In summary, we hypothesize that a Japanese political leader chooses to visit the Yasukuni Shrine only when the following conditions are satisfied:

1) The ruling party to which the leader belongs is conservative/right wing;

2) the government maintains high popularity; and

3) Japan feels a security threat from China.

One might counterargue that a necessary condition does not indicate causation because it is neither correlational nor probabilistic. Such counterargument, however, is an assumption about causation and is not always valid. In fact, as persuasively shown by Goertz and Starr (Reference Goertz and Starr2002), many seminal works have explained causation of international relations with necessary conditions: Gartzke (Reference Gartzke1998, 9), George and Smoke (Reference George and Smoke1974, 529), Keohane (Reference Keohane, Holsti, Siverson and George1980, 137), Putnam (Reference Putnam1988, 429–430), to name but a few.

ARE YASUKUNI VISITS COSTLY SIGNALING, AS WE ASSUME?

Regarding our argument that a security threat affects a Japanese PM's decision about whether to pay homage at Yasukuni Shrine, one might question whether such decisions are actually meant to signal resolve. Indeed, to the best of our knowledge, no PM who has visited Yasukuni has ever publicly asserted that the visit was intended as a signal of resolve. Nevertheless, our argument would be strengthened if it were revealed that a PM recognized in advance the impact a visit would have on relations between Japan and China. Such recognition does indeed appear to have occurred: PM Yasuhiro Nakasone's government published statements about the negative impact of the prime ministerial visit to Yasukuni on Sino-Japanese relations in 1986, after which he refrained from visiting Yasukuni. Furthermore, PM Koizumi's justification for making pilgrimages to Yasukuni shows clearly that he intended to express his unwillingness to bow to Chinese demands.Footnote 9 In 2006, Koizumi responded to reporters’ questions about his repeated visits to Yasukuni, declaring, “Those who would say ‘You should not visit Yasukuni’ are those who say that we should follow what China says. … I wonder if that is the right thing to do” (Maeda and Nantou Reference Maeda and Nantou2006). As Takahara (Reference Takahara, Ross and Feng2008, 234) notes, it was obvious that Koizumi “viewed his visits as part of a diplomatic tug-of-war with China, as Chinese leaders escalated their protests.”

One might suspect that China does not interpret Yasukuni visits in the way we suggest in this article. There is, however, some evidence of Chinese responses that support our explanation. For example, one Chinese scholar argued that “the purpose of Koizumi's visits to Yasukuni was always to signal an assertive diplomatic stance; in other words, a stubborn refusal to yield to Chinese or Korean pressure” (Wang Reference Wang and Breen2008, 77). He further suggested that “a clear tendency existed among the Chinese public and strategic elites to associate Japan's historical memory with its intention to act aggressively again” (Wang Reference Wang and Breen2008, 78). In fact, the Chinese government repeatedly expressed its interpretation that Yasukuni visits reflected Japanese PMs’ diplomatic stance toward China. For example, Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Wang Yi stated in 2001 that the Yasukuni issue is “by no means just an internal matter of Japan, but a touchstone of the government attitude of Japan toward its history of aggression” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2001). Moreover, it should be emphasized that such negative and critical Chinese interpretations of Japanese PMs’ visits to Yasukuni virtually provide an opportunity for a Japanese political leader who wishes to demonstrate Japan's posture of standing firm against China to take strategic advantage of a visit.

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS ACROSS JAPANESE CABINETS

To check the plausibility of our hypothesis regarding the three causal conditions for Japanese PMs’ Yasukuni visits, we present in this section a comparative analysis across a series of Japanese cabinets. The analysis is twofold. First, we examined the relationship between visits and the three conditions across Japanese cabinets after the mid-1980s. We exclude cabinets before 1986 from our analysis because Yasukuni visits became costly only after 1986, as explained below. Second, we compared in depth three of these cabinets—namely, the third Nakasone, first Abe and second Abe cabinets—which shared similar domestic conditions; this allows us to elucidate the effect of international conditions on Yasukuni visits.

The unit of analysis is each cabinet. For example, we study three cases under PM Koizumi, as he led three cabinets. The cabinets of Sosuke Uno and Tsutomu Hata are excluded from our analysis, as each lasted only approximately two months. Thus, the total number of cases analyzed is twenty-two. We decided not to use each PM as the unit of analysis because conditions such as cabinet popularity and international security threats can vary significantly during the time a single PM oversees multiple cabinets. Therefore, a prime minister's term is too long to be a unit of analysis. It may be argued that the unit of analysis should be shorter than each cabinet (e.g., one year), increasing the number of observations. However, Japanese PMs have never visited the shrine more than once in a year.

OUTCOME: VISITS BECAME COSTLY IN THE MID-1980S

The outcomes to be investigated in this study are prime ministerial visits to Yasukuni in public after the mid-1980s, keeping two crucial points in mind. First, it was once natural for a PM and the emperor of Japan to pay homage at the shrine without causing an uproar. Thus, such visits have not always been costly. Second, even after Yasukuni visits became costly, visiting in secret did not lead to criticism, as it remained unknown to all but the political leader himself. Both of these points are explained below.

As mentioned above, visiting the Yasukuni Shrine, at which Class-A war criminals were enshrined in October 1978, has been heavily criticized. However, even after the enshrinement became public in 1979, PMs Masayoshi Ohira, Zenko Suzuki, and Yasuhiro Nakasone visited the shrine between 1979 and 1984 without any criticism from China or other neighbors.

Nakasone's August 15, 1985, pilgrimage to the shrine was the first to be regarded as a controversial act, especially outside Japan. This visit gave rise to particularly harsh condemnation, partly because it was the first official prime ministerial visit to Yasukuni. Unexpectedly, at least for Nakasone, his visit to Yasukuni led to severe reactions and protests from the Chinese government and Chinese society. Students at Peking University held a protest rally on campus and at Tiananmen Square, and anti-Japanese protests spread to various parts of China (Tanaka Reference Tanaka, Hasegawa and Togo2008). In the face of Chinese accusations, Nakasone decided he would not visit Yasukuni again.

These events suggest that Nakasone's 1985 visit was not in itself chosen to signal resolve to China (the focus of this study), as he did not expect such severe criticism from the Chinese. Indeed, it appears he had no idea his visit would be so costly. The crucial point is that the Chinese response transformed a PM's Yasukuni visit into a costly signal indicating an unyielding stance toward China.

On August 14, 1986, the third Nakasone cabinet made public the “Statement by Chief Cabinet Secretary Masaharu Gotoda on Official Visits to the Yasukuni Shrine by the Prime Minister and Other State Ministers on August 15 of this year.” This momentous statement admitted that visiting the shrine possibly caused neighboring countries to question Japan's degree of remorse regarding its war history as well as its determination to maintain peace in Asia. The document stated, “The Government has decided that the Prime Minister will refrain from making an official visit to Yasukuni Shrine tomorrow, August 15.”Footnote 10 Any Japanese PM after Nakasone would therefore have known and fully expected the types of responses they were likely to receive were they to visit the shrine. Accordingly, cabinets after the second Nakasone cabinet are analyzed in this article.

Note that not all Yasukuni visits by PMs after the mid-1980s have faced severe criticism. Kiichi Miyazawa was the only prime minister to visit Yasukuni in the first half of the 1990s; however, he did so in secret. When he ran for the LDP presidential election in October 1992, Miyazawa told a member of the House of Councilors of the LDP, Tadashi Itagaki, who had a close relationship with Nippon Izokukai, that he would visit the shrine once he became PM. Miyazawa also told Itagaki that he had secretly visited the shrine in 1992 or 1993 (Tanaka Reference Tanaka, Hasegawa and Togo2008). Such secret visits naturally generated no public response: visiting Yasukuni does not necessarily lead to denunciation, provided it is done in secret. Thus, if succeeding PMs truly wish to visit the shrine with the exclusive aim to personally mourn the two million soldiers, they can do so in secret, as Miyazawa did. In other words, a visit in public (whether official or not) may be viewed as having a purpose other than merely paying tribute to those who perished in war. In summary, the cabinets that chose to publicly visit Yasukuni after 1985 were the first Hashimoto cabinet, the first to third (inclusive) Koizumi cabinets, and the second Abe cabinet.

DOMESTIC CAUSAL CONDITIONS: POLITICAL IDEOLOGY AND POPULARITY

In measuring the character of a cabinet's political ideology, we consider a cabinet conservative when the prime minister of the cabinet is a member of the LDP or the Japan New Party. Among the political parties in Japan during this period, these were the only two conservative parties to produce PMs.

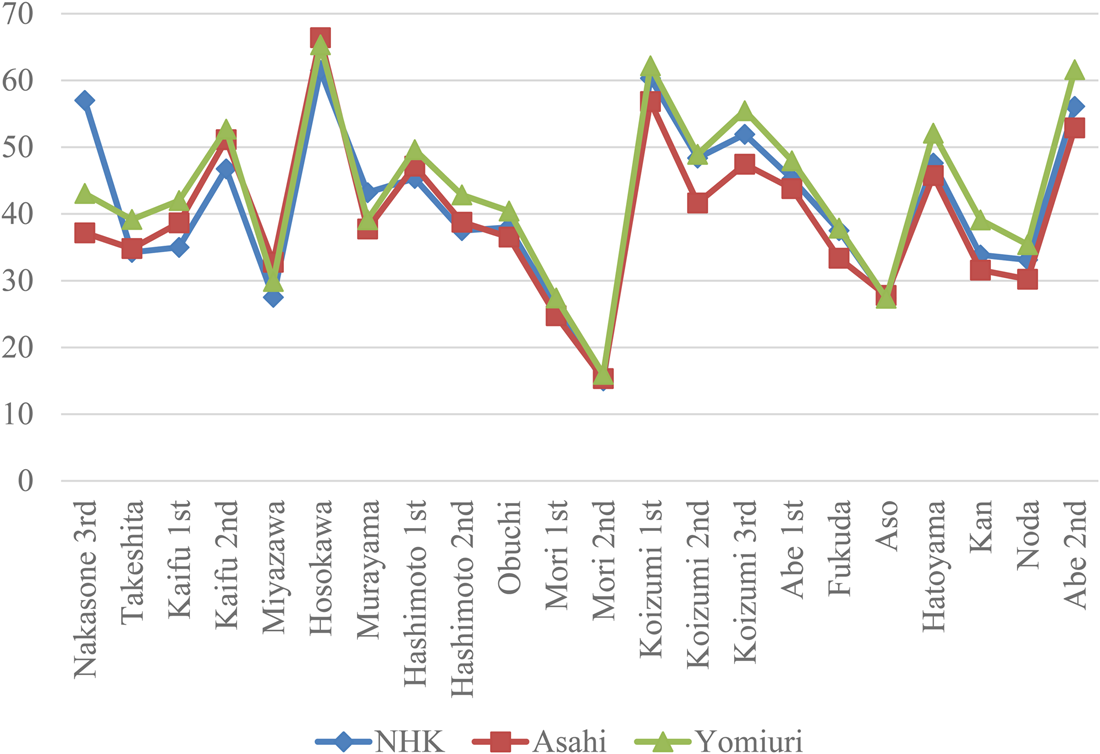

We measure the popularity of cabinets by their approval ratings, as recorded by the Nippon Hoso Kyokai's (NHK) Broadcasting Culture Research Institute, Yomiuri Shimbun, and Asahi Shimbun. NHK is Japan's national public broadcasting organization. Yomiuri Shimbun is a conservative newspaper, as well as Japan's largest, and Asahi Shimbun is a liberal paper, and Japan's second largest. Figure 1 shows the changes in average support rates for each cabinet surveyed by the three institutions from August 1985 to December 2014. Table 1, in turn, shows the average approval ratings for each cabinet, with data rounded to whole numbers.

Figure 1 Average supporting rates for each cabinet

Table 1 Average Approval Rates for Each Cabinet

Bold figure indicates a value higher than the average for all cabinets.

We counted a cabinet as enjoying high popularity when its average approval rating was higher than the average for all cabinets in at least two of the three surveys. Thus, cabinets with above-average popularity were regarded as having high popularity and those below average as having low popularity. The cabinets of Nakasone (third), Kaifu (second), Hosokawa, Hashimoto (first), Koizumi (first, second, and third), Abe (first and second), and Hatoyama had high popularity ratings.

THE INTERNATIONAL CAUSAL CONDITION: PERCEPTION OF SECURITY THREAT

As for the third condition, to measure Japan's perception of the security threat posed by China, we examined three factors: (1) whether Japan's power is declining relative to that of China, (2) whether Japan recognizes that China has assertive intentions or behaves aggressively, and (3) whether Japan discerns weakening commitment from the United States, increasing its fear of abandonment (Hughes Reference Hughes2016; Lind Reference Lind2016). The first two factors—the “capabilities and intentions” of a threatening country—are often identified as the main sources of threat perception for any country, not just Japan (Singer Reference Singer1958; Walt Reference Walt1987). The third factor also has a considerable influence on whether a state, whose security depends on its alliances, feels secure or not (Snyder Reference Snyder1997). Given Japan's reliance on the Japan–US alliance for its national security, the third factor—any weakening of that commitment—cannot be dismissed in light of Japan's perception of a security threat.

We investigated the first factor—whether Japan's power is declining relative to China's—by examining whether Japan's material power was declining relative to that of China in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) and military expenditure. Figure 2 indicates that Japan's GDP growth ceased in the mid-1990s while China's increased gradually in the latter half of the 1990s and rapidly in the 2000s, surpassing Japan in 2008 for the first time in modern history—and it continues to rise.

Figure 2 Nominal GDP of Japan and China

Figure 3 shows that the mid-1990s were a critical time in terms of power relations between Japan and China regarding military expenditures. The increase in Japanese military expenditure almost ceased, whereas China's expenditure began to increase in the mid-1990s, surpassing Japan's in 2004 and climbing to three times that of Japan around 2012. Following the logic of power transition theory, which proposes that war is most likely to occur when a rising challenger increases in power and overtakes a dominant power (Levy Reference Levy, Ross and Feng2008; Organski Reference Organski1958), we conclude that Tokyo has had good reason to fear Beijing since the mid-1990s, at least in terms of the distribution of power (Mearsheimer Reference Mearsheimer2014).

Figure 3 Military expenditure of Mapan and China (bil US$)

In summary, once Japan's overall power had begun its gradual decline relative to China's in the mid-1990s, the latter came to be regarded as a threat to Japan, at least structurally. The mid-1990s were a critical time, during which the power relations between China and Japan changed.

As for the second factor—Japan's perception of China's threat—we considered certain events since the mid-1990s that have had a negative impact on Japan's perception of China's threat or on Sino-Japan relations (Johnston Reference Johnston2003; Reference Johnston2013). Needless to say, it remains difficult for analysts to assess a country's “genuine” threat perception (including threatening countries’ “genuine” intentions), but we may be justified in discerning a country's threat perception by considering specific assertive actions by its adversary. In the present case, we conducted the investigation by examining academic work by prominent experts on Sino-Japan relations. First, to measure the actions of China that are perceived to be threatening by Japanese cabinets, we picked out the two books based on the three criteria. If one chooses books according to the following criteria, he/she will choose the same books: 1) Authors of the books are prominent Japanese scholars on Japan–China relations. 2) The books analyze long-term Japanese foreign policy on China so that the measurement of each cabinet's perception would be done compared to other cabinets’ and be reliable. 3) The books are the latest ones so that they cover even recent Japanese cabinets that our paper analyzes. Following these three criteria, we chose Takahara and Hattori (Reference Takahara and Hattori2013) and Kokubun et al. (Reference Kokubun, Soeya, Takahara and Kawashima2014). Second, we coded a cabinet having the threat perception if either or both of the books describe a cabinet that faces threatening Chinese actions and there is little contradiction in the description of the threat perception between the books. Regarding the second Abe cabinet, which is not covered by the books, we code its perception according to our case study in the section titled “The Second Abe Cabinet.” Third, we used newspapers to check whether the description of China's threatening actions by the two books (such as the dates of the actions) is correct. In this way, the Appendix presents a list of specific Chinese actions and policies described in such materials as damaging to bilateral relations between Japan and China, and worsening Japan's level of security. We concluded that the Japanese cabinets that faced such assertive Chinese actions would have felt that Japan's security was threatened by China. The list of Chinese actions shows that it has only been since the mid-1990s that Japanese administrations have faced such assertive behavior. As noted above, the mid-1990s were a critical period in terms of changes in security relations between China and Japan.

Finally, regarding the third factor in Japan's perception of China as a threat—its fear of abandonment by the United States—the US has undoubtedly been the single most important ally of Japan since 1952. However, it does not necessarily follow that Japan has experienced no anxiety regarding US security commitments. In particular, since the disappearance of the Soviet threat at the end of the Cold War, the significance of this military alliance has been challenged. For example, PM Ryutaro Hashimoto, who visited Yasukuni officially in July 1996 for the first time in about a decade, signed the Japan–US Joint Declaration on Security in April 1996, following the Taiwan Strait crisis and Chinese nuclear tests. Subsequently, in September 1997, Japan and the United States agreed on the 1997 Japan–US Defense Guidelines. In the Security Declaration, they “reaffirmed” the importance of the alliance and promised to “cooperate in the situations that arise in the areas around Japan,” through the revision of the bilateral 1978 Guidelines (Green Reference Green2003). The Security Declaration emphasized “the importance of the military commitment of the United States in Asia” (Tanaka Reference Tanaka1997, 344). These efforts to reinforce the security relationship between Japan and the United States reflected an increasing uneasiness on the part of Japan regarding US commitment in the latter half of the 1990s, which appeared to wane in the post-Cold War era.

Japan's fear of abandonment seems to have continued to rise in the twenty-first century. Samuels (Reference Samuels2007, 70–71) argues that Japan has had to “contemplate Chinese coercion on the high seas” and “to recalculate the prospect that the United States might not stand by its side indefinitely.” Indeed, the Koizumi cabinet demonstrated its positive attitude toward military cooperation with the United States. Koizumi said in the Diet in 2003 that Japan has “only a single ally, the United States … [and] must not be isolated in international society” (Samuels Reference Samuels2007, 99). As a consequence of Japan's growing fear of abandonment, Koizumi sent defense forces to Iraq and the Indian Ocean, despite strong opposition from the Japanese public.

Furthermore, PM Abe has made further efforts to enable Japan to exercise the right to collective self-defense, which was not permitted in previous constitutional interpretations. These acts may also reflect an increase in Japan's fear of abandonment by the United States, an issue that is examined in more detail in the following section. Thus, as in the case of the first two factors, it was in the mid-1990s that Japan began to experience a fear of abandonment by the United States and made efforts to strengthen its alliance.

Summing up the discussion of Japan's perception of a threat to its security, the cabinets under which Japan perceived a threat from China might be identified.Footnote 11 Given the relative power of Japan and China, and Japan's fear of abandonment, Japan has had good reason to perceive a security threat from China since the mid-1990s (Liff and Ikenberry Reference Liff and John Ikenberry2014; Ross Reference Ross2006). However, without concrete aggressive behavior from China, the Japanese government appears not to have perceived a threat sufficiently severe to encourage Japanese PMs to visit the controversial Yasukuni Shrine. Rather, it was only when Japan faced concrete aggressive actions, not simply words, from China after the mid-1990s (see Appendix) that Japanese leaders had good reason to take the Chinese threat seriously, and a Japanese PM visited the Yasukuni shrine. The cabinets that faced threats from China were those of Murayama, Hashimoto (first), Mori (first), Koizumi (first, second, and third), Aso, Hatoyama, Kan, Noda, and Abe (second).

ANALYSIS OF JAPANESE CABINETS AFTER THE MID-1980S

Table 2 shows the three causal conditions for a Yasukuni visit and the outcomes for all cabinets. The three causal conditions, each with two values (Yes or No / High or Low), produce eight possible combinations. Our investigation recorded six of these combinations, indicating enough variety to be reliable.

Table 2 Relationships among Causal Conditions and Visits

Bold indicates satisfaction of all three conditions for a visit.

As mentioned above, our hypothesis expects visits to Yasukuni if and only if all three of the necessary conditions are present: a conservative ideology, high popularity, and a high perception of threat. This is because, according to our hypothesis, each of the three causal conditions is necessary for a visit. That is, the co-presence of the three conditions is necessary for a visit to occur. Table 2 clearly supports our hypothesis. Japanese cabinets have chosen to visit Yasukuni only when all three conditions were met simultaneously.Footnote 12 We coded 22 cabinets for the presence of these conditions, and only five met the criteria. However, those cabinets account for all the Yasukuni visits. The outcome demonstrates that visiting the controversial shrine is so costly, both domestically and internationally, that all three conditions are required for a decision to be made for a Japanese PM to visit.

Furthermore, it is notable that a necessary condition hypothesis can be logically changed into a sufficient condition one via the contrapositive operation. That is, our findings also indicate that each of the three followings is a sufficient condition for a Japanese PM not to visit Yasukuni: a non-conservative ideology, low popularity, and low perception of threat from China. Table 2 confirms that each of these is indeed a sufficient condition for non-visit (17 cabinets). That is, our hypothesis explains the results of all the 22 cases, both the visits (by five cabinets) and non-visits (by 17 cabinets).

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS ACROSS SIMILAR CASES

We undertook case studies of three cabinets (the third Nakasone, the first Abe, and the second Abe cabinets) to confirm more closely the causal relationship between the international condition (perceived security threat) and visits to Yasukuni. These cabinets were selected on the basis to their similarity or comparability.Footnote 13 Among these three cabinets, only the second Abe cabinet chose to visit the shrine, although all three shared the relevant domestic conditions. The PMs of all three cabinets were leaders of the LDP, a conservative party, and enjoyed high popularity. Our focus on these three cases with the same domestic conditions, but different international conditions, helps us to elucidate the effect of Japan's perception of a security threat on a PM's decision about whether to visit the war-linked shrine.

THE THIRD NAKASONE CABINET

The third cabinet of Nakasone was popular, as shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. The cabinet was established in June 1986 following victory in both the upper and lower house elections. Nakasone served concurrently as head of the conservative political party (LDP) in Japan and as prime minister. Thus, the cabinet satisfied the two domestic conditions for a visit. Indeed, Nakasone, who had visited Yasukuni 10 times during his two preceding cabinets, planned to make a pilgrimage to the shrine again after the elections (Hattori Reference Hattori2015, 67). However, Japan faced no security threat from China at the time. Rather, if anything, China perceived a threat from Japan, a rising power whose economy was experiencing rapid growth (a “bubble economy”) at the time and the “former invader.”Footnote 14 In this security context, Nakasone did not need to show Japan's resolve to stand firm against China through a controversial visit. Indeed, before deciding not to visit Yasukuni, he told Foreign Minister Tadashi Kuranari and Chief Cabinet Secretary Masaharu Gotoda, who agreed, “We must carefully consider the impact of the visit on international relations.”Footnote 15

Thus, Nakasone decided not to visit Yasukuni at the time, in the face of Chinese accusations. Further, he also sought a way to move the enshrined Class A criminals to another shrine (Hattori Reference Hattori2015, 61). He dismissed Masayuki Fujio, the minister of education, who had attempted to whitewash Japan's wartime atrocities. Moreover, under the Nakasone administration, the Ministry of Education established a new guideline for Japanese history textbooks, incorporating “the neighboring country clause,” which required publishers to take into consideration historical incidents between Japan and neighboring Asian nations as necessary for international understanding and cooperation. As a result, the extent of textbooks’ descriptions of Japan's actions in Asia during wars and the colonial era increased.

In short, the third Nakasone cabinet met the two necessary domestic conditions for a visit—namely, political ideology and popularity. However, the lack of the third necessary condition, a security threat from China, prevented Nakasone from paying homage at the controversial shrine.

THE FIRST ABE CABINET

There is no doubt that PM Abe, president of the LDP, was one of the leading conservative right-wing nationalist politicians in Japan. Following his election to parliament in 1993, Abe repeatedly expressed nationalistic and conservative views about issues ranging from national security and diplomacy to education. The Congressional Research Service report by the United States characterized Abe as follows: “Abe embraces a revisionist view of Japanese history that rejects the narrative of Imperial Japanese aggression and victimization of other Asians” (Chanlett-Avery et al. Reference Chanlett-Avery, Manyin, Cooper and Rinehart2013, 4). In fact, Abe went so far as to claim that Class-A war criminals convicted by the Tokyo tribunal after the 1945 capitulation were not criminals under domestic law (Abe Reference Abe2006).

Furthermore, the first Abe cabinet was popular, as shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. The two domestic conditions may be expected to have made it possible for PM Abe to pay homage at Yasukuni during his first administration.

However, Abe did not visit Yasukuni during his premiership. According to our argument, it can be inferred that Abe's decision not to visit was influenced by the favorable security environment enjoyed by the cabinet at the time. Clear evidence exists to support this inference. Abe made an official visit to China during his first cabinet. A summit meeting with President Hu Jintao took place during Abe's time in Beijing, after which they released a joint Japan–China Press Statement in which it was “confirmed that they would accelerate the process of consultation on the issue of the East China Sea, adhere to the broad direction of joint development, and seek a resolution acceptable for both sides.” They agreed also to the necessity of building a “strategic relationship of mutual benefit.”Footnote 16 Sino-Japanese relations, which were deadlocked during the preceding Koizumi administrations, steadily improved after the meeting. Indeed, China refrained from assertive actions during the first Abe cabinet's period in power (see Appendix), which contributed to a reduction in the need for a signal of resolve from Abe.

Thus, the first Abe cabinet met only two of the three necessary conditions for a Yasukuni visit—political ideology and popularity. The lack of the third necessary condition, brought about by the amelioration of Tokyo's relationship with Beijing, kept Abe from visiting the shrine.

THE SECOND ABE CABINET

In contrast to the two cabinets described above, PM Abe did visit the Yasukuni Shrine during his second administration on December 26, 2013. What were the reasons for this? The third Nakasone and the second Abe cabinet satisfied two of the conditions for a visit to Yasukuni: the PM's membership in the LDP and high approval ratings. However, as confirmed above, the first Abe cabinet, which satisfied the same two conditions, did not visit the controversial shrine. Our hypothesis, accordingly, suggests that Japan's perception of a security threat might have played a crucial role in Abe's decision to visit the shrine in 2013. This section examines three aspects of the second Abe cabinet's perception of a security threat: power relations, fear of US abandonment, and China's assertive actions.

Power relations are the first area of investigation. The distribution of capabilities between Japan and China in terms of economics and military expenditures continued to change in favor of the latter during the mid-1990s. PM Abe, in his second premiership, was acutely aware of this situation. For example, Abe stated at the committee on Fundamental National Policies (Diet Joint Committee) on April 17, 2013, that the balance of security in East Asia was threatened by the fourfold increase in China's military expenditure in just a few years, part of a thirtyfold increase over 24 years. To maintain a balance in the region and keep Japan from facing a crisis, Abe actually took decisive action to increase defense spending in fiscal year 2013—the first increase in 11 years.Footnote 17

With regard to Japan's fear of US abandonment, the relative decline of US power also appeared well under way at this time and was accelerated by the 2008 global financial crisis and drastic Pentagon budget cuts, generating an increasing concern about US commitment to the defense of its allies (Brooks, Ikenberry, and Wohlforth Reference Brooks, Ikenberry and Wohlforth2013). Furthermore, US president Barack Obama's failure to enforce the “red line” on Syria's chemical weapons in 2013 highlighted the problem of US commitment around the world (Miller Reference Miller2014).

PM Abe was certainly anxious about potential US abandonment: this was clearly underscored by the following remarks from Abe, which may have affected his decision to visit Yasukuni in 2013:

We welcome the Obama administration's policy called the “pivot to Asia,” because it is a contributing factor to the safety and peace of the region. I think this pivot policy is playing an indispensable role in enhancing the deterrence of the US–Japan alliance. … President Obama mentioned and stated very clearly that the Senkaku Islands would be an area where Article 5 of the security treaty would be applied. I think he was the first US president to state this very clearly. So in that sense, we place the fullest confidence in his policy. (Ignatius Reference Ignatius2015, emphasis added)

Finally, with regard to China's assertive behavior, a number of actions deepened Abe's concerns about Japan's security. In December 2012, immediately after being designated PM, Abe singled out a specific threat from China. He noted that China's maritime activities would lead to the South China Sea becoming “Lake Beijing,” which would scare its neighbors, and that “Japan must not yield to the Chinese government's daily exercises around the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea” (Abe Reference Abe2012). In addition, Abe accused China of repeating its intrusion into Senkaku territorial waters and Japan's air defense identification zone (ADIZ) at the Lower House Committee on the Budget on February 28, 2013. He stated that Japan needed to strengthen its own efforts to deal with the severe security threat, rather than responding passively to changes in US strategy.Footnote 18

Nevertheless, China's assertive behavior continued to escalate later in 2013. On April 27, China, for the first time, officially described the Senkaku Islands as a “core interest” (Japan Times 2013). Abe showed a firm stance in response to these actions by China, stating that “[p]rovocations on our territorial land, waters, and sovereignty are continuing. … Without doubt, Senkaku is Japan's unique territory, historically and in terms of international law. I have absolutely no intention to retreat, even by an inch” (Asahi Shimbun 2013). Furthermore, on November 23, 2013, the Chinese government set an air defense identification zone over a large swath of the East China Sea, including the area over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, warning that any aircraft flying in the zone and not obeying orders would be subject to “defensive emergency measures” by Chinese armed forces (Ministry of National Defense 2013). Abe reacted to this unprecedented security challenge from Beijing by declaring at the Upper House Committee on Audit on November 25 that, in response to China's unilateral attempt to alter the regional status quo by force, his cabinet continued to be absolutely resolved to protect Japan's territorial land, waters, and air, and to deal with Beijing firmly.Footnote 19

PM Abe aimed to make good on his promise. In December, the Abe cabinet demonstrated that Japan would be prepared to defend itself by approving a new national security strategy, including a defense budget increase.Footnote 20 According to this new strategy, over the next five years Japan would purchase hardware, including drones, stealth aircraft, and amphibious vehicles. Abe's government stated that “the strategy is a measured and logical response to a real and increasing threat” (BBC 2013). There was no doubt that this was aimed at China.

PM Abe and his cabinet faced a severe security threat up until the end of December 2013. This was characterized by a decline in the power of both Japan and the United States relative to that of China, increasing unease about US defense of its allies, and an explicit security challenge from China. It was in this deteriorating security environment that Abe decided to make a controversial Yasukuni visit on December 26, 2013, against China's demands.Footnote 21

CONCLUSION

This study explored when and why Japanese political leaders have chosen to visit the Yasukuni Shrine in public, despite the high political costs of such visits. We consider that the political cost is one of the major conditions which have leaders dare to do so. Specifically, such a visit is used as a means to signal the strength of the country's resolve. Such visits are so costly that three conditions must exist for a Japanese leader—as the prime minister of a past perpetrator country—to select it as a strategy. The conditions are a conservative government, high popularity, and a security threat from a past victim country. We conducted a systematic comparative analysis to confirm the validity of our argument, which showed that the three conditions are all necessary for a Yasukuni visit.

We derived a falsifiable hypothesis based on the costly signal theory in IR instead of focusing only on domestic factors. Further, we focused on set-theoretic causation, or necessary conditions, rather than probabilistic causation, and we conducted a systematic comparative analysis, rather than depending on a small-N case study. This enabled us to explain the pattern of Japanese leaders’ decisions to visit Yasukuni clearly and consistently.

Regarding Japanese leaders’ Yasukuni visits, or any other acts that represent a denial of history, the focus has tended to be on the negative impact of the denial on diplomatic relations. The present article has highlighted the opposite: such denials, reflected in decisions to visit the war-linked Yasukuni Shrine, are caused by the state of security relationships between countries. We have shown that the logic of international politics and security may induce a leader of Japan, a past perpetrator country, to visit Yasukuni as a signal of the country's resolve to defend itself against threats from a past victim country.

Our argument implies, counterintuitively, that normative pressure regarding war responsibility—such as condemning a Japanese PM's Yasukuni visit—might not always deter Tokyo from making such decisions. Paradoxically, normative pressure, by making the visit more costly, might make it an effective means for a Japanese PM to send a costly signal.

Lastly, according to our argument, whether future Japanese PMs’ visits to Yasukuni will depend partly on a change in the security situation in East Asia. For example, if China continues to rise as a formidable power, which would heighten Japan's perception of threat from China, Japanese leaders who belong to a conservative party and are popular might choose to visit the shrine to signal the resolve of defending Japanese security. However, even in that case, if China's threat induces a much stronger commitment from the US to protect Japan, Japanese PMs would be less likely to visit the war shrine. On the other hand, in case China should rise to the extent that the US could no longer compete with China in East Asia, having to counter a serious security threat from China unilaterally, Japanese leaders might have a stronger incentive to visit the shrine, or might make a policy reversal for Japan to become a “security partner” of China, and would likely choose not to pay homage at the shrine because doing so could antagonize China. Of course, nobody can predict exactly what will happen in the future of East Asian security under a quite historic power transition. However, there is no doubt that Japanese leaders cannot escape from the security dynamics in East Asia and make a decision of whether to visit the historically contentious place without considering their own security environment.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Taisuke Fujita and Hiroki Kusano declare none.

Appendix: China's Actions and the Major Events Considered to have Heightened Japan's Threat Perception