Introduction

Testosterone and cortisol are the end-products of two coregulated neuroendocrine axes, the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axes. HPA and HPG axes typically upregulate each other, with parallel elevations in testosterone and cortisol.Reference Liening, Stanton, Saini and Schultheiss1 However, under chronic or high stress, higher testosterone levels can downregulate the activity of the HPA axis and lead to lower cortisol levels.Reference Kapoor and Matthews2

Individual differences in HPA–HPG interactions appear to be important for both brain function and behavior,Reference Montoya, Terburg, Bos and van Honk3 with at least some of these relationships found to be sex- and/or age-specific.Reference Gaffey and Martinez4,Reference Maeng and Milad5 For example, testosterone:cortisol (TC) ratio modulates activation in several cortical and subcortical brain regions. TC interactions also lead to variation in aggression levels during late childhood and early adolescenceReference Nguyen, Jones and Elgbeili6 and may impact the frequency of anxiety disorders during adulthood.Reference Maeng and Milad5 In contrast to TC ratio’s activational and behavioral effects, its organizational and cognitive effect is much less understood. Yet, differences in TC ratio are also likely to lead to structural variation in several brain networks and cognitive performance.

Many sexually dimorphic cortical and subcortical structures, such as the hippocampus, contain a high concentration of androgen and glucocorticoid receptors, at least in rodent models.Reference Tabori, Stewart and Znamensky7,Reference Kalafatakis, Giannakeas and Lightman8 Human studies have also shown that age- and sex-specific levels of circulating androgens and glucocorticoids do influence morphometric properties of several cortical and hippocampal regions.Reference Neufang, Specht and Hausmann9–Reference Nguyen, McCracken and Ducharme13 For instance, in postpubertal boys, lower testosterone levels were associated with greater cortical thickness in the left hemisphere, including the posterior cingulate gyrus, precuneus, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and later the anterior cingulate gyrus.Reference Nguyen, McCracken and Ducharme13 In contrast, in early prepubertal girls, higher testosterone levels were associated with greater cortical thickness in the right hemisphere, in the somatosensory cortex, but this was reversed in late postpubertal girls.Reference Nguyen, McCracken and Ducharme13

Because hormonal interactions tend to affect multiple brain regions simultaneously, structural covariance is an imaging parameter that is well suited to explore organizational effects of TC ratio. Structural covariance refers to interindividual structural differences in one brain region with interindividual structural characteristics in another region that is directly or indirectly connected to that first area.Reference Alexander-Bloch, Giedd and Bullmore14 Brain maturation in children and adolescents aged 5–18 years has been extensively studied by analyzing structural covariance. Studies have found significant associations of cortico-hippocampal structural covariance with levels of adrenal and gonadal hormones in typically developing children, adolescents, and young adults.Reference Nguyen, Lew and Albaugh12,Reference Farooqi, Scotti and Yu15 Sex-specific associations were also revealed when examining testosterone-related covariance of prefrontal-hippocampal areas, which predicted lower executive function in boys, but not girls.Reference Nguyen, Lew and Albaugh12 Hence, structural covariance may be sensitive enough to index both differences in TC ratio and in cognitive performance.

Extant literature supports the notion that examination of both hormones, and their relative levels, may be a better predictor of alterations in brain structure and cognition compared to levels of these hormones in isolation.Reference Nguyen, Jones and Elgbeili6,Reference Platje, Popma and Vermeiren16–Reference Mehta and Josephs18 Notwithstanding, the presence of mixed findings within a small number of human samples is not conducive to the construction of well-validated a priori hypotheses for specific cortical areas. As such, the goal of this study was to test for associations among TC ratio, cortico-hippocampal structure, and standardized tests of executive, verbal, and visuospatial function in a longitudinal sample of typically developing 4–22-year-old children and adolescents.

We hypothesized that (i) TC ratio may influence the development of top-down and/or bottom-up connections between hippocampal and cortical areas because of the known sensitivity of the hippocampus to T and C; (ii) this TC-related cortical-hippocampal covariance may be associated with lower scores on cognitive tests (i.e. working memory, verbal fluency, and executive function); and (iii) this association between TC ratio, cortico-hippocampal covariance, and cognitive measures would vary according to age and sex.

Methods and materials

Sampling and recruitment

We used the Objective 1 database (433 subjects, aged 4.6–18.3 years) of the multisite National Institute of Health Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study of Normal Brain Development (NIHPD), aimed at characterizing healthy brain structural development and its relations to behavior. A population-based sampling method was used to recruit a demographically representative sample of the US population in terms of socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity. Rigorous exclusion criteria were applied to select for developmentally healthy children. Exclusion criteria included pre and perinatal factors known to disrupt brain development, such as maternal smoking, drinking or drug use during pregnancy, obstetric complications, physical/medical or growth characteristics such as low height/weight, and history of neurological disorders or abnormal neurological exams. Behavioral/psychiatric assessments were used to exclude children with a current/past treatment for language disorder (simple articulation disorders not exclusionary) or a lifetime history of Axis I psychiatric disorder (except simple phobia, social phobia, adjustment disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, enuresis, encopresis, nicotine dependency). Additional details are described elsewhere.Reference Evans19 All experiments involving human subjects were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was provided by parents and participants over 18 years, whereas those under 18 years provided assent. The experiments used a mix of cross-sectional and longitudinal design that required each subject to undergo magnetic resonance brain imaging (MRI) at 2-year intervals, with a maximum of 3 scans over 4 years (full age range 4–22 years). MRI data that survived strict quality control (see Section 2.3) with existing hormonal and cognitive/behavioral measures were used for final analysis. Totally, 355 scans within 225 subjects (128 females) were analyzed for examining the relationship between TC ratio and cortico-hippocampal structural covariance and scans within subjects for examining the relationship between cortico-hippocampal structural covariance and cognition/behavior (see Table 1).

Table 1. Sample characteristics per visit

The characteristics of the sample used for the analysis of the relationship between TC ratio and cortico-hippocampal structural covariance (see Section 2.4.1). Total scans = 355 (208 females); total participants = 225 (128 females); participants who completed 1 scan = 122 (68 females); 2 scans = 76 (40 females); 3 scans = 27 (20 females). The testosterone and cortisol AUC values were calculated from the average of each hormonal level at time 1 and time 2. All continuous variables were centered in regard to their means in the analyses. The means of collection time, hormonal levels at time 1 and 2 were calculated and used as control variables.

Hormonal and pubertal measures

To measure hormonal levels, four 1–3 cm3 salivary samples were collected from children throughout the research visit (2 precognitive testing, 2 postcognitive testing). Saliva samples were collected within 1–2 hours after completion of the MRI scan. The samples were assayed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) methods, and the intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variations (COVs) were 6.1% and 13.5% for testosterone and 3.1% and 7.2% for cortisol (Salimetrics ELISA, State College, PA; Salimetrics Salivary ELISA Kit, State College, PA). Hormonal data from precognitive testing (Time 1) and postcognitive testing (Time 2) samples were averaged separately, as seen in Table 1. The collection times of samples varied from early morning to early afternoon, though no awakening time samples were taken (see Table 1). To achieve a mix of cross-sectional and longitudinal data, the procedures were repeated in the following visits every 2 years over a 4-year period, with a maximum of three hormonal measurements per visit.

Salivary sampling allows for the effective measurement of the nonprotein bound, free, biologically active portions of circulating hormonal levels.Reference Khan-Dawood, Choe and Dawood20 The measured hormones may affect brain structures and functions and are known to cross the blood–brain barrier freely, according to studies of brain–hormone interactions demonstrating, for instance, that central testosterone levels as measured in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are reliably predicted by peripheral levels.Reference Kancheva, Hill and Novák21 For both testosterone and cortisol levels, salivary measures show strong correlations with those found in serum levels.Reference Francavilla, Vitale and Ciaccio22 There is evidence that both cortisol and testosterone levels follow diurnal patterns for both sexes.Reference Brambilla, Matsumoto, Araujo and McKinlay23–Reference Ankarberg and Norjavaara25 Pubertal stage is known to affect hormone levels, notably testosterone increases in both sexes, but to a greater extent in males.Reference Bae, Zeidler and Baber26 We accounted for these confounders that impact testosterone and cortisol levels by introducing covariates of collection time, sex, pubertal stage (accounting for adrenarche), and estradiolReference Raven, de Jong, Kaufman and In Men27 in any statistical models including TC ratio (see Section 2.5).

Pubertal maturation of children was measured using the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS) during interviews with a physician. This scale has been shown to have good reliability (coefficient alpha: 0.77) and validity (r 2 = 0.61–0.67)Reference Petersen, Crockett, Richards and Boxer28. Pubertal development occurs as a function of hormonal levels and therefore their effects can be hard to disentangle. However, one has to take care not to test the effects of a hormone on the brain (e.g. testosterone) while at the same time controlling for the physiological effects of that hormone on the body (e.g. facial hair, voice changes, muscle mass), as this causes both problems of multicollinearity and clinical interpretability. In addition, several prior studies from our group have shown that specific hormonal levels are more significant predictors of brain trajectories than pubertal staging.Reference Nguyen, Lew and Albaugh12,Reference Nguyen, McCracken and Ducharme13 Nonetheless, to attempt to control for the bodily effects of androgens other than testosterone (e.g. DHEA, androstenedione), we adjusted TC ratios at each timepoint to reflect the child’s evolving pubertal status, accounting for the physical manifestations of adrenarche (e.g. skin changes, axillary/pubic hair), using residuals from mixed effect models.

In addition, because studies suggest that the area under the curve (AUC), or hormonal trajectory over time calculated from samples collected before and after a stressor, may represent a more reliable measure of hormonal interactions and HPA/HGP axis reactivityReference Khoury, Gonzalez and Levitan29 than hormonal levels collected at a single timepoint, we created a TC AUC variable (also adjusted for pubertal status as described above). Specifically, testosterone and cortisol AUCs were computed separately by averaging the levels at time 1 (precognitive testing) and time 2 (postcognitive testing) and multiplying the result by the time interval.Reference Fekedulegn, Andrew and Burchfiel30 Logarithmic values of AUCs were used to correct for skewness in the hormone distributions, and testosterone AUC was divided by cortisol AUC to yield a TC AUC ratio.

Neuroimaging measures

During each MRI, participants first completed a 3D T1-weighted (T1W) Spoiled Gradient Recalled (SPGR) echo sequence in 1.5 Tesla scanners. Most scanners obtained 1 mm isotropic data sagittally with entire head coverage. The following 2D multislice (2 mm) dual echo fast spin echo sequence was carried out to produce T2-weighted (T2W) and proton density-weighted images. Fully automated structural image analysis was used to process each quality-controlled magnetic resonance image through the CIVET pipeline (version 1.1.9) developed at the Montreal Neurological Institute. Previous papers by our research group have described the processing steps in detail.Reference Nguyen, McCracken and Ducharme13,Reference Nguyen, McCracken and Ducharme31 Briefly, images were linearly registered to the ICBM152 template,Reference Lyttelton, Boucher, Robbins and Evans32 corrected for intensity nonuniformityReference Sled, Zijdenbos and Evans33 and classified into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid, and background using a neural net classifier (INSECT).Reference Zijdenbos, Forghani and Evans34 Next, images were fit with a deformable mesh model to extract the 2D inner (WM/GM interface) and outer (pial) cortical surfaces for each hemisphere, which generates 40 962 cortical points on each hemisphere, before doing a nonlinear registration of both cortical surfaces for each hemisphere to the ICBM152.Reference Lyttelton, Boucher, Robbins and Evans32 Next, the reverse of the linear transformation was applied on the images of each subject to achieve cortical thickness estimations at each cortical point in the subject’s native space, before calculating cortical thickness at each cortical point.

To derive total brain volume (TBV), we used the sum of total gray matter volume (GMV), total white matter volume (WMV), and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) inside the brain. We subtracted CSF found outside the brain (but still within the skull) for our calculation. We derived a second variable, TBV-GMV, by summing WMV and intracerebral CSF. TBV-GMV (instead of TBV) was used as a covariate for our analyses because we examined cortical thickness (grey matter) and therefore did not want to control for our variable of interest.

To derive hippocampal volume from MRI data, we used a fully automated segmentation method that has been validated in human subjects.Reference Collins and Pruessner35 In this method, a large MRI data set (n = 80) of young healthy adults was used as a template library for manually labeled hippocampal volumes.Reference Pruessner, Collins, Pruessner and Evans36 The manual segmentation was conducted by four different raters, and intraclass intrarater reliability varied between r = 0.94 for the left and r = 0.91 for the right hippocampus.Reference Pruessner, Li and Serles37 As a result, a fully automated method was obtained to combine segmentations from a subset of “n” most similar templates using label fusion techniques. After each template constructed an independent segmentation of the participant via the ANIMAL pipeline,Reference Collins and Evans38 a thresholding step was done to eliminate CSF and thus producing “n” different segmentations. Subsequently, the segmentations at each voxel were fused together using a voting strategy that assigns the label with the most votes from the “n” templates to the voxel. This label fusion technique combines multiple segmentations for both minimum errors and maximum consistency between segmentations and has an optimal median Dice Kappa of 0.886 and Jaccard similarity of 0.796 for the hippocampus.Reference Collins and Pruessner35

Cognitive measures

Following the first hormonal sampling and the MRI scan, we administered a battery of cognitive and neurobehavioral tests. The California Verbal Learning Test – Children’s Version (CVLT-C) and the California Verbal Learning Test – II (CVLT-II) are standardized tests of verbal learning and memory in the context of immediate, short-term, and long-term delayed recall of words.Reference Strauss, Sherman, Spreen and Spreen39 We identified five subtests appropriate to this study that measure verbal memory: long-delay (cued and free) recall, short-delay (cued and free) recall, and total number of words recognized. The CVLT-C and CVLT-II are both widely used measures of verbal learning and memory and have demonstrated excellent internal consistency.Reference Strauss, Sherman, Spreen and Spreen39 The CVLT-C is normed for children as young as 4 and the CVLT-II is normed for children and adults over 16.Reference Strauss, Sherman, Spreen and Spreen39 In addition, CVLT-C has been shown to be an ecologically valid measure in predicting children’s subsequent placement in special education.Reference Strauss, Sherman, Spreen and Spreen39

The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) assesses executive function in terms of problem-solving abilities as rated by parents. It comprises a Behavioural Regulation Index (Inhibit, Shift, Emotional Control) and a Metacognition Index (Initiate, Working Memory, Plan/Organize, Organization of Materials, Monitor).Reference Strauss, Sherman, Spreen and Spreen39 This test was scored in ecological, real-world settings, accurately reflecting the complex, priority-based nature of everyday decision-making.Reference Strauss, Sherman, Spreen and Spreen39 Studies have also shown adequate to high test–retest reliability (r ≈ 0.70 – 0.89 for parent ratings depending on the subtest) and high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha values ≈0.80 – 0.98) in the BRIEF.Reference Strauss, Sherman, Spreen and Spreen39

In contrast to the ecologically based BRIEF, the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) consists of computerized tests that assesses nonverbal, spatial abilities in dealing with simple shapes or geometric designs including the spatial span subtest, which assesses short term visual spatial working memory by presenting the respondent with a visual sequence and asking them to recreate it from memory by touching the appropriate targets on the screen.Reference Strauss, Sherman, Spreen and Spreen39,Reference Luciana40 This battery has been well established in pediatric studies as a valid measure for brain–behavior relations.Reference Luciana40 Pediatric test results have shown that the item sets for adults can be tested in children with high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for subtests range from 0.73 for reaction time to 0.95 for performance on the self-ordered search task).Reference Luciana40 Studies with adult populations also demonstrate moderate test–retest stability coefficients ranging from 0.60 to 0.70.Reference Luciana40

The Woodcock-Johnson III (WJ III) test is a battery of cognitive tests evaluating intellectual abilities.Reference Strauss, Sherman, Spreen and Spreen39 WJ III has good internal reliability and rigorously developed content.Reference Strauss, Sherman, Spreen and Spreen39 We chose the WJ III letter–word identification and passage comprehension subtests in order to directly measure verbal and language skills in reading with no motor skills involved. Letter–word identification is a good measure of visual attention, asking the child to practice visual detection/identification and pronunciation of individual letters as well as the recognition of visual word forms.Reference Strauss, Sherman, Spreen and Spreen39 Test–retest reliability has been shown to be high to very high for these subtests, ranging from 0.80 to above 0.90.Reference Strauss, Sherman, Spreen and Spreen39

Statistical analyses

We used SurfStat (Matlab toolbox designed by Keith J. Worsley) and SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to perform the neuroimaging and cognitive/behavioral analyses, respectively. Mixed-effects models (accounting for within- and between- subject variance) were used to analyze longitudinal data in the sample of children and adolescents aged 4–22 years. Factors that may affect hormonal levels (i.e. age, sex, scanner, handedness, collection time, TBV-GMV) were controlled in the models. To be more conservative, and due to lack of supporting literature, no region of interest (ROI) was identified prior to neuroimaging analyses. For all analyses, random field theory (RFT, P < 0.05) was used to correct for multiple comparisons across the whole brain. Neuroimaging studies have commonly used RFT and preferred it over Bonferroni corrections.Reference Worsley, Evans, Marrett and Neelin41 All continuous variables in the analyses (i.e. TC AUC ratio, age, TBV-GMV, collection time, CTh, mean hippocampal volume) were centered with regard to their means.

Testosterone-cortisol AUC ratio and cortico-hippocampal structural covariance

Using mixed-effects models, we tested for (i) the relationship between TC AUC ratio and hippocampal volume; (ii) the relationship between TC AUC ratio and whole-brain CTh; and (iii) the interaction between TC AUC ratio and structural covariance of hippocampal volume with whole-brain CTh, controlling for effects of age, sex, handedness, scanner, time of saliva collection, and TBV-GMV. Clusters, t-statistics, and P-values were also obtained from the interaction term at each significant vertex of whole-brain CTh. Estradiol may also influence the effects of TC AUC ratio on cortico-hippocampal covariance and thus the models were retested with this added covariate to elucidate independent effects of TC vs. estradiol.

We also examined the impact of age and sex on the relationship between TC AUC ratio and structural covariance of hippocampal volume with whole-brain CTh. Triple mixed-effects models with interaction terms of “TC AUC × Hippocampus × Age” and “TC AUC × Hippocampus × Sex,” as well as a quadruple model with the term of “TC AUC × Hippocampus × Age × Sex” were tested on whole-brain CTh for significance.

Cortico-hippocampal structural covariance and cognitive/behavioral measures

The whole-brain CTh values of the brain clusters found to be significant in Section 2.5.1 were averaged and tested on the cognitive/behavioral scores for significance, with the interaction terms found to be significant in Section 2.5.1. Effects of age, sex, handedness, scanner, and total brain volume were controlled in the mixed-effect models.

Mediation effects of cortico-hippocampal structural covariance

To assess whether cortico-hippocampal structural covariance, between the CTh hippocampal volumes within regions found to be significant in Sections 2.5.1 and 2.5.2, mediate the indirect effects of TC AUC ratio and cognitive/behavioral measures, a formal Sobel–Goodman test was performed. Each relationship (between TC AUC ratio and cortico-hippocampal covariance and then between cortico-hippocampal covariance and cognitive/behavioral measures) was tested independently. This method allows for flexibility in dealing with mixed cross-sectional and longitudinal data (multiple scans per subject, different number of scans per subject), and is thus preferable for our analyses. The beta coefficients and P-values were extracted from the significant interaction terms in the: (i) mixed-effects model of TC-related cortico-hippocampal covariance; (ii) age-related model of TC-related hippocampal covariance; and (iii) sex-related model of TC-related cortico-hippocampal covariance. Results from each model were then entered separately into the Sobel–Goodman test calculator (http://quantpsy.org/sobel/sobel.htm). The control variables used in all mediation analyses remain the same as in Sections 2.5.1 and 2.5.2.

Results

Sample characteristics

After quality control of MRI data and exclusion of participants without hormonal measures, we used a longitudinal sample of 225 participants (females = 128) aged between 4.88 and 18.24 years (mean ± sd = 12.48 ± 3.29) at the time of first visit. Participants completed a maximum of three visits during a 4-year period (i.e. full age range 4–22 years), resulting in a total of 355 scans (females = 208) for MRI data collection. Table 1 describes the characteristics of hormonal and neuroimaging data and covariates of interest across visits.

TC ratio and cortico-hippocampal structural covariance

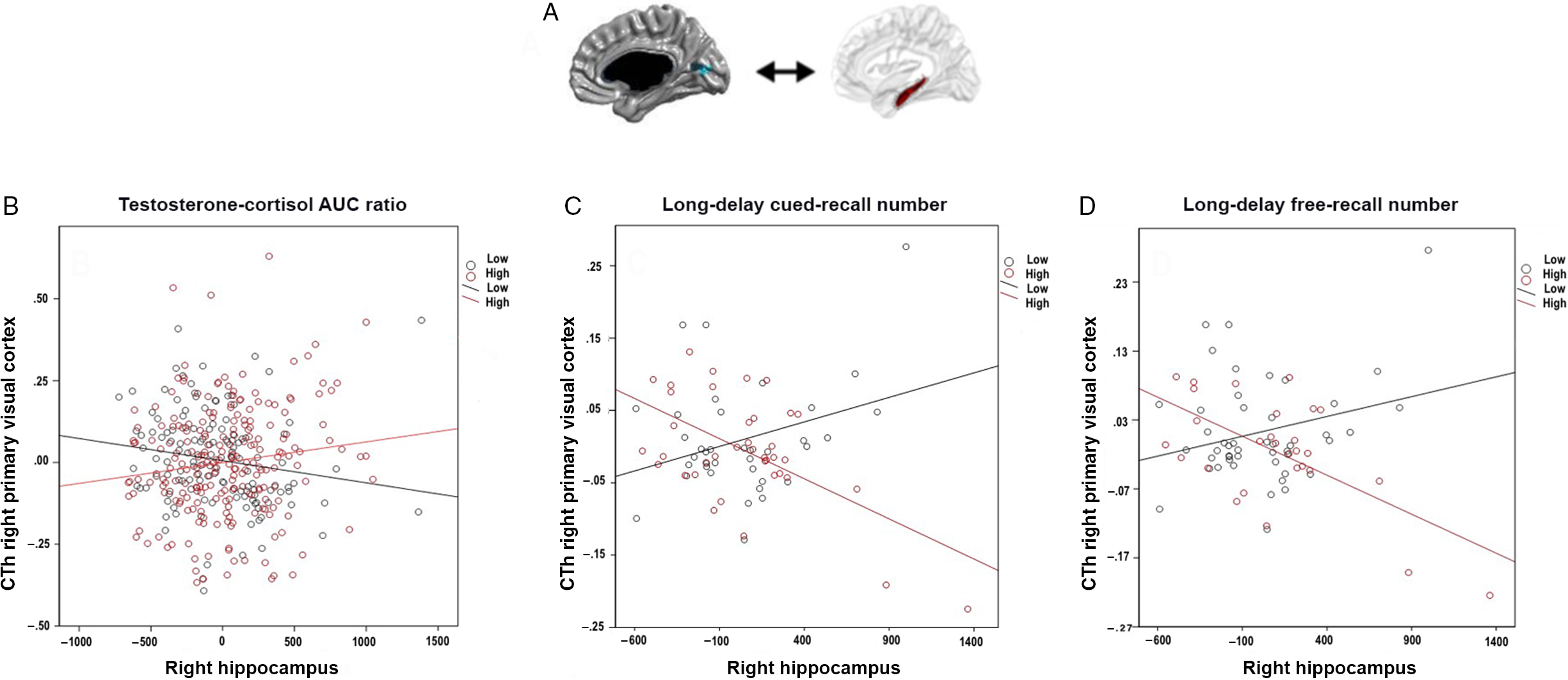

As shown in Fig. 1 (Panels A and B), whole-brain analyses (controlled for multiple comparisons using RFT) revealed that the coordinated growth between the hippocampus and the right primary visual region (Brodmann area 17; peak vertex, r = 0.198, se = 0.536, P = 0.0049) varied as a function of TC AUC ratio, with a similar trend in the left hippocampus. Greater TC AUC ratios (≥−0.0729) were associated with greater coupling in hippocampal and cortical growth in this visual region. Controlling for estradiol did not significantly change observed relationships but diminished them slightly.

Fig. 1. Associations between testosterone:cortisol (TC) ratio, occipito-hippocampal structural covariance, and long-delay verbal recall. Panel A shows the right primary visual region (Brodmann area 17) for which cortical thickness (CTh) significantly covaried with right hippocampal volume according to TC ratio. Similar trends were present for the left hippocampus. Panel B shows the positive relationship between right V1 CTh and right hippocampus (i.e. positive occipito-hippocampal structural covariance) as related to higher TC ratio (≥−7.29 × 10−2, calculated in AUC). In contrast, a negative occipito-hippocampal structural covariance was associated with lower TC ratio (<−7.29 × 10−2, calculated in AUC). Panels C and D show that a more positive occipital-hippocampal structural covariance (similar to that seen with higher TC ratios) is associated with lower long-delay verbal recall on the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) (<0.86, for cued recall; <13.5 for free recall), but a negative covariance with higher scores (≥0.86 for cued recall; (≥13.5 for free recall). *Notes: The occipital area shown in this fig is not a predefined region-of-interest. Rather, this is the only region across the whole brain whose relationship with the hippocampus significantly varied as a function of TC ratio in analyses corrected for multiple comparisons across the whole brain using random field theory (RFT). In addition, even though they were analyzed as continuous variables, TC ratio (Panel B) and cognitive scores (Panel C, long-delay cued recall on the CVLT; Panel D, long-delay cued recall on the CVLT) are displayed in this fig as dichotomous variables, in order to better visualize their interaction with cortico-hippocampal structural covariance. The y-axes represent the standardized residuals of CTh (accounting for control variables - as listed in section 2.5.1). The x-axes represent the volume of right hippocampus centered according to the mean.

Age-related effects of TC ratio on cortico-hippocampal structural covariance

As shown in Fig. 2 (Panels A and B), there was an age-related relationship between TC AUC ratio and coordinated growth in the hippocampus and CTh in the left posterior cingulate cortex (PCC; Brodmann 31; r = 0.247, se = 0.0532, P = 0.001). TC AUC ratio had an effect opposite to that of age, such that there was a shift toward greater coupling in PCC-hippocampal growth at higher TC AUC ratios, while age was associated with lower covariance between these regions.

Fig. 2. Age interaction between testosterone:cortisol (TC) ratio, parieto-hippocampal structural covariance, reading and short-delay verbal recall. This fig shows age-related associations between TC ratio, parieto-hippocampal structural covariance and letter-word identification as measured by Woodcock-Johnson III (WJ III)) and short-delay free verbal recall (as measured by the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT)). Panel A shows the region of the left posterior cingulate cortex (PCC; Brodmann 31) for which there are age-specific variation in cortico-hippocampal covariance according to TC ratio. Panel B displays the age-related associations between TC ratios and PCC-hippocampal covariance. TC ratio tended to ‘counteract’ the effect of age (shown in years), such that there was a shift toward more positive PCC-hippocampal structural covariance with higher TC ratios (in light grey). In other words, as age increased, cortical thickness (CTh) of the PCC tended to decrease and hippocampal volume to increase; such that there was a shift toward a more negative covariance between these regions in older subjects; in contrast, higher TC ratios had the inverse effect. Panels C and D display the age-related associations between PCC-hippocampal covariance and reading abilities (as measured by WJ letter-word identification scores) as well as free short-delay verbal recall on the CVLT. An age-related covariance pattern similar to that seen with higher TC ratios (see Panel B) was seen, i.e. a shift toward a more positive PCC-hippocampal structural covariance was associated with higher reading performance and short-delay verbal recall. *Notes from Fig. 1 also apply to Fig. 2.

Sex-related effects of TC ratio on cortico-hippocampal structural covariance

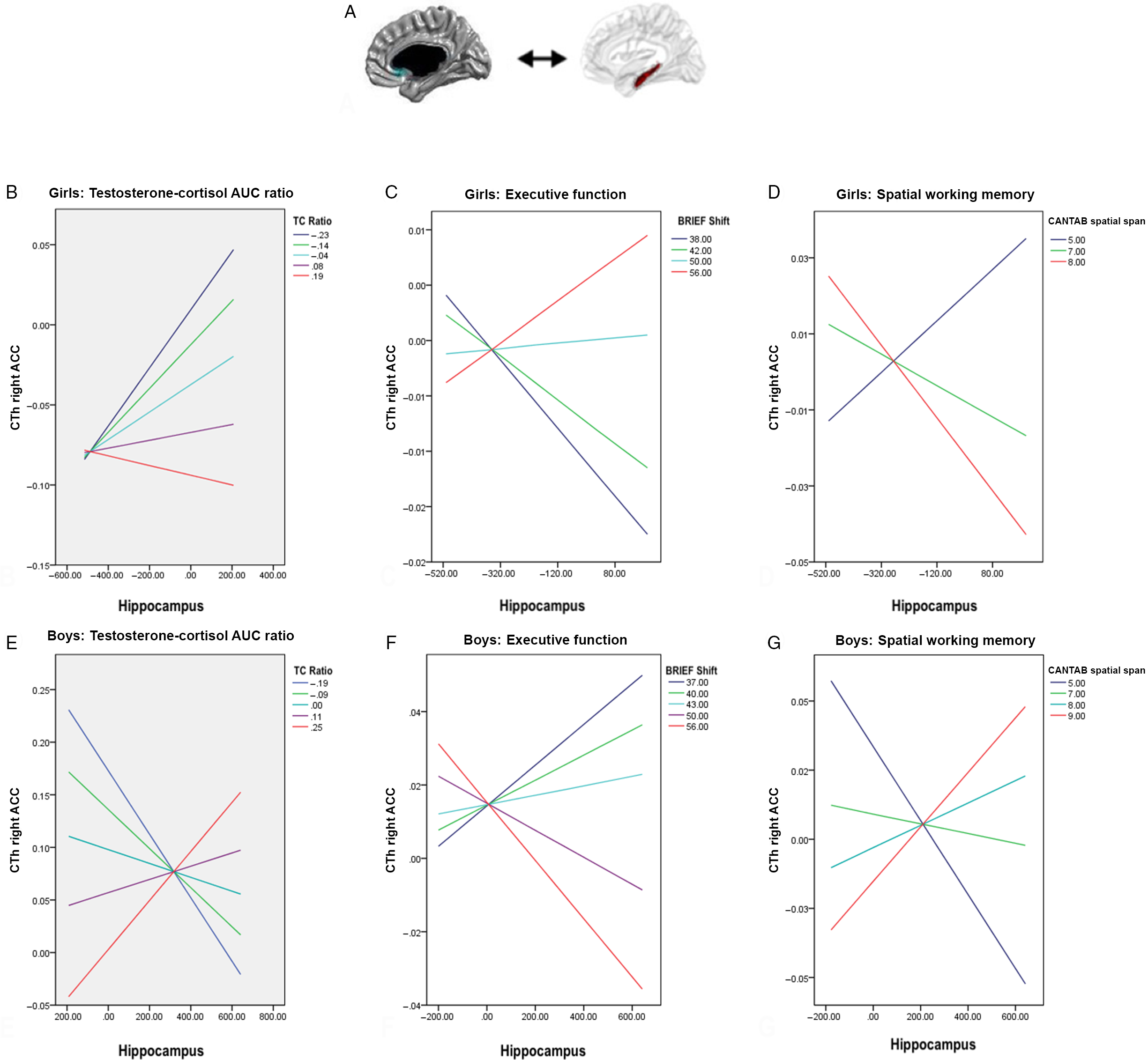

As shown in Fig. 3 (Panels A, B, and E), there was a sex-related relationship between TC AUC ratio and coordinated growth between the hippocampus and the right anterior cingulate cortex (ACC; Brodmann areas 24 and 33; r = 0.246; se = 0.0532; P = 0.000016). Boys showed more coordinated growth between these regions at higher TC AUC ratios, while girls showed less covariance between these areas at higher TC AUC ratios. That is to say, at higher TC ratios, boys and girls showed opposite patterns of structural covariance. On the other hand, there was no significant “sex by age” interaction between TC ratio and cortico-hippocampal structural covariance.

Fig. 3. Sex interaction between testosterone:cortisol (TC) ratio, prefrontal-hippocampal structural covariance, executive function and spatial memory. Panel A shows the region of the right anterior cingulate cortex (ACC; Brodmann 24/33) for which cortical thickness (CTh) covaried with mean bilateral hippocampal volume according to TC ratio. Panel B displays the shift toward a more negative ACC-hippocampal structural covariance with higher TC ratios in girls. In turn, a more negative ACC-hippocampal structural covariance (as seen with higher TC ratios) is associated with lower executive function (as measured by the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) shift subtest (Panel C) and higher spatial working memory (as measured by the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) spatial span subtest (Panel D) in girls. Panel E displays the shift toward a more positive ACC-hippocampal structural covariance with higher TC ratios in boys. In turn, a more positive ACC-hippocampal structural covariance (as seen with higher TC ratios) was associated with lower executive function (as measured by the BRIEF shift subtest (Panel F) and higher spatial working memory (as measured by the CANTAB spatial span subtest (Panel G) in boys. *Notes from Fig. 1 also apply to Fig. 3.

Testosterone-cortisol AUC ratio, cortico-hippocampal structural covariance, and cognition

As shown in Fig. 1 (Panels C and D), the greater coordinated growth between the hippocampus and the primary visual cortex seen at higher TC AUC ratios was associated with lower scores (<0.86, for cued recall; <13.5 for free recall) on two components of verbal working memory as measured by CVLT: the long-delay cued verbal recall (r = −0.00537, se = 0.00216, P = 0.016) and the long-delay free verbal recall (r = −0.00675, se = 0.00289, P = 0.049). As shown in Fig. 4, the relationship between TC AUC ratio and verbal working memory was significantly mediated by occipito-hippocampal covariance (CVLT long-delay cued (P = 0.039) and free (P = 0.049) recall).

Fig. 4. Indirect effects of testosterone:cortisol (TC) AUC ratio on cognitive performance mediated by cortico-hippocampal structural covariance. (A) Age-related differences in posterior cingulate cortex (PCC)-hippocampal covariance mediated the relationship between TC AUC ratio and letter-word identification as measured by Woodcock-Johnson III (WJ III). (B) Occipito-hippocampal structural covariances mediated the relationship between TC AUC ratio and both long-delay cued- and free-recall as measured by the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT). (C) Sex-related differences in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)-hippocampal covariance mediated the relationship between TC AUC ratio and spatial working memory as measured by the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) spatial span subtest.

Age-related effects of PCC-hippocampal covariance on cognition

As shown in Fig. 2 (Panels C and D), there were age-related associations between PCC-hippocampal covariance and different components of short-term visual attention and verbal recall, as measured by performance on the WJ III letter–word identification (r = −0.00000807, se = 0.00000310, P = 0.01) and CVLT free short-delay verbal recall (r = −0.00000558, se = 0.00000251, P = 0.028), respectively. The age-related covariance pattern seen at higher TC AUC ratios (described in Section 3.2.1) was associated with better performance on both these measures (i.e. higher reading performance and short-delay verbal recall). As shown in Fig. 4, age-related differences in PCC-hippocampal covariance mediated the relationship between TC AUC ratio and visual attention (WJ III letter–word identification subtest; P = 0.021), but not short-term verbal recall (CVLT free short-delay verbal recall; P = 0.066).

Sex-related effects of ACC-hippocampal covariance on cognition

As shown in Fig. 3 (Panels C, D, F, and G), there were sex-related associations between ACC-hippocampal covariance and shifting abilities (child’s ability to change strategy and move between different problems/tasks/activities), as measured by the BRIEF shift subscale (r = 0.0224, se = 0.0109, P = 0.042); as well as spatial span, as measured by CANTAB (r = −0.00445, se = 0.00178, P = 0.013). In boys, the greater coordinated growth between the hippocampus and the ACC seen at greater TC AUC ratios were associated with lower shifting abilities and greater spatial span. In girls, the greater coordinated growth between the hippocampus and the ACC seen at lower TC AUC ratios were associated with the opposite cognitive profile, i.e. greater shifting abilities and lower spatial span. As shown in Fig. 4, sex-related differences in ACC-hippocampal covariance significantly mediated the relationship between TC AUC ratio and spatial span (CANTAB spatial span; P = 0.028), but not shifting abilities (BRIEF shift; P = 0.061).

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the role that relative levels of testosterone vs. cortisol may play in age- and sex-related cortico-hippocampal growth and cognitive development, based on the premise that any of the activational effects of TC ratio previously reported during adulthood are actually rooted in TC-related differences in brain structure occurring in childhood and adolescence. We document novel, indirect, and adverse effects of TC ratio on verbal executive function through its influence on the coordinated growth of the hippocampus and visual areas. There were also beneficial, age-related and indirect effects of TC ratio on a specific component of visual attention (differentiation between letters and words), through its direct impact on PCC-hippocampal covariance. Interestingly, the magnitude of these beneficial effects on brain and cognitive development diminished as children aged. Finally, while TC ratio had opposite effects on ACC-hippocampal growth in boys and girls, both sexes appeared to benefit, demonstrating greater performance on a test of visuo-spatial attention.

While sex- and age-specific associations between testosterone, verbal, and spatial function, as well as between cortisol, working memory and executive function have been shown,Reference Panizzon, Hauger and Xian11,Reference Hamson, Roes and Galea42–Reference Butler, Klaus, Edwards and Pennington44 it remains unclear how the effects TC ratio unfold during childhood and adolescence. Apart from our group’s paper cited above, only one other study looked at testosterone levels and child’s cognition using a standardized battery and reported that extremes of IQ in prepubertal children aged 6–9 (n = 284) were associated with lower salivary testosterone levels in boys, but not girls.Reference Ostatnikova, Celec and Putz45 Regarding cortisol, in a group of 152 preschoolers, children with lower cortisol stress reactivity levels, who had also experienced maternal corporal punishment in the past year, exhibited worse global executive function and working memory (compared with children exhibiting higher cortisol stress reactivity).Reference Xing, Yin and Wang46

Adverse effects of TC ratio on executive function through alterations in cortico-hippocampal structure are reminiscent of our prior findings showing that higher testosterone predicted lower executive function as a function of cortico-hippocampal covariance.Reference Nguyen, Lew and Albaugh12 Notable differences with previous results include the fact that developmental differences in TC ratio are important for both boys and girls, while variation in testosterone levels had a detrimental impact on cognitive performance only in boys. Our prior study also demonstrated effects of testosterone only on ACC-hippocampal growth, while TC ratio is shown here to coordinate growth between the primary visual cortex (BA17) and the hippocampus. While the BA17 is thought to primarily affect visuospatial, rather than verbal, working memory,Reference Salmon, Van der Linden and Collette47 both components of executive function are related, and visuospatial memory plays an important role in verbal comprehension.Reference Pham and Hasson48 The inherent interconnection between visual, spatial, and verbal abilities may explain both the coordinated growth between visual and hippocampal areas as a function of TC ratio and the importance of these areas in verbal working memory.Reference Kintsch, Patel and Ericsson49 Though the occipital area was not a predefined ROI, one might speculate that it is sensitive to steroid hormones perhaps due to evolutionary pressures for the visual cortex to adapt rapidly to changing circumstances as signaled by hormonesReference Mattson50 or sex-specific needs regarding visual representation matching sex-specific HPA/HPG function and brain structure.Reference Handa and McGivern51

We also demonstrate that PCC-hippocampal growth significantly varied across the age span as a function of TC ratio. In essence, TC ratio appeared to counteract the effects of age on cortico-hippocampal growth to some extent, though any beneficial effects on cognitive performance decreased in magnitude as children aged. These findings are consistent with prior observations from our group; we and others have supported the notion that the developmental effects of testosterone are nonlinear and change as a function of age, with prepubertal children more likely to benefit from higher testosterone levels because their levels do not cross over into the “neurotoxic” range seen in postpubertal adolescents.Reference Nguyen, McCracken and Ducharme13,Reference Foradori, Weiser and Handa52 We now show that developmental effects of cortisol are likely to follow similar nonlinear trajectories. Animal studies have shown a greater number of glucocorticoid receptors in the hippocampus of prepubertal rats as compared to adults, which may contribute to a greater sensitivity to cortisol in younger rats.Reference Green, Nottrodt, Simone and McCormick53 This suggests that any beneficial effects of androgen and glucocorticoid hormones on brain maturation are more likely to be significant in younger children vs. late adolescents and adults in whom much greater levels may eventually have detrimental effects. We previously observed similar age-related variation in the effects of estradiol on brain structure and cognitive performance, linking estradiol, PCC-amygdalar covariance, and visual attention (letter-word identification).Reference Nguyen, Jones and Gower54 These results provide further evidence that the polymorphic effects of testosterone on cognition are composed of both direct (activation of androgen receptors and effects on cortico-hippocampal development) and indirect effects (conversion to estradiol, activation of estradiol receptors, and effects on cortico-amydalar development).Reference Nguyen, Lew and Albaugh12,Reference Farooqi, Scotti and Yu15,Reference Farooqi, Scotti and Lew43,Reference Nguyen, Jones and Gower54

We also document sex-specific contributions of TC ratio to prefrontal-hippocampal development. However, sex differences in brain structure as a function of TC ratio did not result in sex differences in cognition in our study. In fact, greater TC ratios were related to greater spatial span and lower shifting abilities in both boys and girls. Further, the indirect effects of TC ratio on cognition through structural covariance only affect spatial span, not shifting abilities. Interestingly, we have also shown sex-specific associations between ACC-hippocampal covariance and the ratio between dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and cortisol,Reference Farooqi, Scotti and Yu15 as well as cognitive benefits of DHEA:cortisol ratio in both boys and girls.Reference Farooqi, Scotti and Lew43 In comparison with estradiol -a metabolite of testosterone, DHEA is a precursor hormone for testosterone, i.e. a lower potency androgen that eventually gets converted to the higher potency androgen testosterone after several enzymatic conversion steps.Reference Labrie, Luu-The, Labrie and Simard55 In contrast to testosterone, we have shown that greater DHEA levels (and greater DHEA:cortisol ratios) influence cortico-hippocampal and cortico-amygdalar growth in such a way that cognitive tasks relying on cortex-heavy, or top-down processes (cortex to hippocampus/cortex to amygdala) were optimized, and bottom-up (or hippocampus/amygdala-heavy) tasks were compromised.Reference Farooqi, Scotti and Yu15,Reference Farooqi, Scotti and Lew43 Here, we show the opposite pattern for greater testosterone vs. cortisol levels, such that bottom-up tasks (i.e. spatial span and visuo-spatial attention, which rely heavily on the hippocampus), are optimized, while top-down tasks (i.e. verbal executive function) are compromised. Taken together, these results support the concept that steroid hormones play an important role in determining brain and cognitive plasticity during childhood and adolescence through a concerted fine-tuning of steroid-sensitive brain “hubs” including key cortical ACC, PCC, and visual cortices as well as subcortical hippocampal and amygdalar regions. The fact that just a few conversion steps can shift the cognitive effect of these hormones from one end of the spectrum to the other (e.g. DHEA vs. testosterone) or from one structural network to another (e.g. testosterone vs. estradiol) adds credence to the idea that hormone–brain interactions are exquisitely sensitive, and therefore, vulnerable, to internal and external perturbations.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our study include the large, longitudinal developmental data set, including the repeated collection of hormonal, neuroimaging and measures of personality, behavior, and cognition, allowing us to test interactions with age and sex. Limitations include ethical methodological challenges such as the inability to administer androgens or corticosteroids to developing children, and the difficulty in inferring molecular mechanisms linking hormonal levels to brain development from salivary measures of testosterone and cortisol. In particular, we cannot determine whether our findings are primarily a result of testosterone acting through nuclear or membrane androgen receptors (AR) or non-AR pathways.Reference Foradori, Weiser and Handa52 Despite the relatively large size of our sample, it still may have been underpowered to detect age by sex interactions previously found with testosteroneReference Nguyen, McCracken and Ducharme13 and cortisol.Reference Seeman, Singer, Wilkinson and Bruce56 Additionally, a word of caution is warranted in that some effect sizes were small, and may denote statistical rather than clinical significance, especially since our sample was typically developing thereby potentially limiting generalizability to smaller or more heterogenous samples. Finally, some effects of testosterone could be mediated by its precursor DHEA or its metabolite estradiol, and their interactions with cortisol, especially relevant given that hormones were measured through saliva, and not directly from cerebrospinal fluid samples, something that is difficult if not impossible to accomplish outside of experimental animal models. In fact, prior studies from our group suggest this may be the case 15, 43, 54. However, one may argue that the polymorphic effects of the TC ratio actually highlight, rather than undermine the potential usefulness of this ratio as an index of cognitive vulnerability during childhood and adolescence.

Conclusions

This study aimed to document the role of TC ratio in brain and cognitive development, and how it may contribute to cognitive vulnerabilities during adulthood. In examining relative levels of T and C using AUC, our findings contribute to the knowledge of the complex interplay between these hormones and across time rather than examining them in isolation. Interestingly, TC ratio was associated with opposite patterns of structural covariance in boys and girls, but the same cognitive performance. We found overall that TC may alter the coordinated growth of cortical and hippocampal structures such that cortical-heavy, or top-down (cortex to hippocampus) cognitive tasks, including verbal executive function, are impaired, while hippocampal-heavy, or bottom-up (hippocampus to cortex) tasks for instance, visual and spatial attention may be optimized.

Acknowledgments

None.

Financial support

Tuong-Vi Nguyen received funding from the Montreal General Hospital Foundation, the McGill University Health Center Foundation, and the Fonds de Recherche Québec Santé. Data collection for this study was also supported by Federal funds from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (Contract #s N01-HD02-3343, N01-MH9-0002, and N01-NS-9-2314, −2315, −2316, −2317, −2319, and −2320).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and has been approved by the institutional committees at the relevant clinical sites where recruitment took place: Boston Children’s Hospital, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Texas Houston Medical School, Neuropsychiatric Institute and Hospital, University of California, Los Angeles, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and Washington University.

Contribution statement

Christina Caccese and Sherri Lee Jones provided intellectual contributions to the rationale and interpretation the data, contributed to the presentation of data, made tables and figures, and prepared the manuscript for submission. Ally Yu verified and interpreted the data, created the tables and figures, and drafted the initial manuscript. Mrinalini Ramesh performed the data analyses. Marie Brossard-Racine provided intellectual contributions regarding the neuroimaging methods. Tuong-Vi Nguyen conceived of the project, oversaw the data analyses, interpreted the data, provided intellectual contributions to the paper, and revised manuscript drafts. All authors approved the submitted manuscript.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. They are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S204017442100012X