Introduction

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG), severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, accounts for over 285,000 hospital discharges in the United States annually.Reference Wier, Levit and Stranges1 Estimates of severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy vary greatly and range from 0.3% in a Swedish registry to as high as 10.8% in a Chinese registry of pregnant women, with most authors reporting an incidence of 0.5%.Reference Verberg, Gillott, Al-Fardan and Grudzinskas2–Reference Zhang and Cai4 HG can be associated with serious maternal and fetal morbidity such as Wernicke's encephalopathy,Reference Chiossi, Neri, Cavazutti, Basso and Fucchinetti5 fetal growth restriction and even maternal and fetal death.Reference Bailit6, Reference Fairweather7

HG may be defined as persistent, unexplained nausea and vomiting resulting in more than a 5% weight loss, abnormal fluid and nutritional intake, electrolyte imbalance, dehydration and ketonuria.Reference Goodwin8 Symptoms often extend beyond the first trimester and can last throughout the entire pregnancy in as many as one-third of cases leading to extreme weight loss and possibly a state of malnutrition and extended dehydration of pregnancy.Reference Fejzo, Poursharif and Korst9

Despite the fact that it is the most common cause of hospitalization in the first half of pregnancy and is second only to preterm labor for pregnancy overall,Reference Gazmararian, Petersen and Jamieson10 there are very few studies on child outcome of HG and no studies, to our knowledge, on adult outcome, with the exception of two studies on subsequent cancer risk.Reference Henderson, Benton, Jing, Yu and Pike11, Reference Erlandsson, Lambe, Cnattingius and Ekbom12 However, many studies on the long-term outcome of dehydration, starvation and/or anxiety in pregnancy in animal models and humans reveal adverse effects on exposed offspring including cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, neurodevelopmental, cognitive, emotional and behavioral disorders.Reference Mulder, Robles de Medina and Huizink13–Reference Ross and Desai17 Given that HG can be a form of prolonged dehydration, starvation and stress in pregnancy, it follows that long-term outcomes could possibly mimic those identified in these studies. To explore this possibility, we compare adulthood physical, emotional and behavioral diagnoses between individuals exposed to HG in utero and non-exposed controls.

Method

Participants

This study is part of a larger investigation evaluating the genetics and epidemiology of HG. Eligible participants were primarily recruited through advertising on the Hyperemesis Education and Research Foundation Web site at www.HelpHer.org. The inclusion criteria for participants with HG were a diagnosis of HG and treatment with intravenous (i.v.) fluids and/or total parenteral nutrition/nasogastric feeding tube. Because multiple or abnormal gestations may be associated with HG due to unique physiological pathways, women with these types of pregnancies were excluded.

Procedure: part 1

In the first part of the study, participants with HG were asked to submit their medical records confirming diagnosis and treatment with i.v. fluids and/or parenteral or nasogastric tube feeding, and complete an online survey (survey 1, http://www.helpher.org/HER-Research/2007-Genetics/) regarding family history, treatment and outcomes. A total of 279 women with an HG diagnosis completed the survey. In the family history section of survey 1, participants answered the following question:

In her most severe (with respect to nausea) pregnancy, did your biological mother have..?

(1) no nausea and vomiting

(2) very little nausea and vomiting

(3) typical nausea and vomiting

(4) more severe morning sickness

(5) HG

(6) other or unsure (please describe in text box)

(7) unknown

Immediately preceding the question, the following definition was given to them to refer to for their mother's pregnancy: HG-persistent nausea and vomiting with weight loss that interfered significantly with daily routine, and led to need for (i) i.v. hydration or nutritional therapy [feeding by an iv (TPN) or tube (NG) through the nose] and/or (ii) prescription medications to prevent weight loss and/or nausea/vomiting.

Procedure: part 2

In the second part of the study, all 279 participants who completed survey 1 were then asked to fill out a second survey (survey 2), in order to (i) confirm a positive or negative diagnosis of HG in their mother while pregnant with each sibling, as reported for at least one pregnancy in the family history section of survey 1 and (ii) report on health complications in their siblings. Among the 117 participants who reported HG in their mothers in survey 1, 55 responded to survey 2, confirmed HG in their mothers, and reported on health complications in 87 siblings who were exposed to HG in utero. This group of 87 HG-exposed siblings represents the cases in this study.

Among the 162 participants with HG who reported that their mothers did not have HG, 95 completed survey 2, confirming their mother did not have HG while pregnant with their siblings and reporting on health complications in 172 siblings who were not exposed to HG in utero. This group of 172 non-exposed siblings of participants, who had HG themselves, represents the control group in this study, and controls for the potential confounding factor of family history of HG.

Procedure: summary

In summary, the study design is shown in Figure 1: the offspring of the participants are currently too young to obtain long-term data on the effects of in utero exposure to HG. However, because HG runs in families,Reference Zhang, Cantor and Macgibbon18 a large proportion of participants have a mother who had HG, and therefore, were able to report on the current health of their adult siblings exposed to HG during their mother's affected pregnancy. Thus, participants, with HG provided information about their mother's obstetric history, and the presence (n = 117) or absence (n = 162) of HG (using definitions from survey 1) with each pregnancy involving their siblings. A second questionnaire (survey 2) was then used to collect information about the participants’ siblings. Cases are defined as offspring from a pregnancy reported to have been complicated by HG. Controls are defined as offspring from a pregnancy NOT complicated by HG. A total of 87 cases and 172 controls were identified.

Fig. 1 Study design.

Data analysis

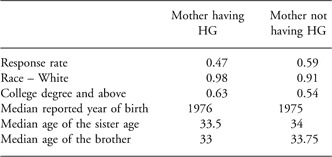

The 279 participants who filled out survey 1 were compared for a number of variables including response rate, number of siblings, age, ethnicity and education. Response rate, ethnicity and education were compared using a two-tailed Fisher's exact test, number of siblings and age of siblings were compared using the Wilcoxson rank-sum test (Mann-Whitney U or robust t-test) in addition to the conventional t-tests and kolmogorov–smirnov tests.

We report on the psychological and behavioral diagnoses and other health complications are not included herein. The frequency of diagnoses was compared among the cases exposed to HG and the controls using two-sided Fisher's exact test. Some cases and controls had more than one diagnosis in a given group and therefore the overall affected rate is the number of affected siblings out of the total number of siblings rather than the number of diagnoses out of the total number of siblings.

This study has been approved by Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), University of Southern California IRB no. HS-06-00056 and University of California, Los Angeles IRB no. 09-08-122-01A.

Results

Matched-pairs analysis

Response rate to survey 2 regarding sibling diagnoses was close to 50% for all participants. Respondents were primarily White and born in the mid-1970s. On average, over 50% had a college degree. At the time of the survey, female and male siblings were primarily in their mid-30s. Respondents were well matched for all variables tested; no significant differences were found between groups (Table 1).

Table 1 Survey participants are well matched

HG, hyperemesis gravidarum.

P-values for all: >0.05; no significant difference was found between groups.

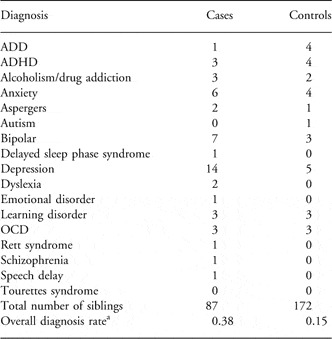

Psychological and behavioral disorders

Psychological and behavioral disorders reported by participants on behalf of their siblings are listed in Table 2. In all, 38% of cases are reported to have a psychological and behavioral disorder, as compared to 15% of controls. In this study, adults exposed to HG in utero are significantly more likely to have a psychological and behavioral disorder than non-exposed adults (OR = 3.57, P = 0.000035, 95% CI = 1.87–6.9). Analysis of the two largest subcategories independently reveals that depression and bipolar are both significantly more common in the HG-exposed group (for depression OR = 6.35, P = 0.0002 and for bipolar OR = 4.90, P = 0.0338).

Table 2 Psychological or behavioral diagnoses

ADD, attention deficit disorder; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

P = 0.000035, OR = 3.57, 95% CI = 1.87–6.9.

aCases or controls with more than one diagnosis were counted only once.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore fetal exposure to HG and adult emotional and behavioral outcomes. Herein fetal exposure to HG is significantly correlated to an increased risk of emotional or behavioral disorders in adulthood including depression, bipolar disorder and anxiety. Thirty-eight percentage of exposed offspring are reported to have a behavioral or emotional disorder. Previous studies on nausea and vomiting and pregnancy and neurodevelopment have somewhat conflicting results on the effects of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) and neurodevelopment. Martin et al.,Reference Martin, Wisenbaker and Huttunen19 showed that nausea beyond the first trimester was associated with lower task persistence at the age of 5 years and more attention and learning problems at the age of 12 years, whereas Nulman et al.,Reference Nulman, Rovet and Barrera20 showed that higher intelligence scores in NVP-exposed children. Although we did not address intelligence in our study, consistent with Martin et al.,Reference Martin, Wisenbaker and Huttunen19our results suggest HG may have an effect on the emotional or behavioral development of exposed individuals, perhaps independent of intelligence.

The mechanism for exposure to HG and abnormal neurodevelopment is unknown, but there are several hypotheses offered in the literature. First, maternal anxiety and stress are common during HG pregnancies.Reference Pirimoglu, Guzelmeric and Alpay21, Reference Tan, Vani, Lim and Omar22 Maternal stress, primarily during the first and second trimesters, has been linked to permanent changes in neuroendocrine regulation and behavior in offspring. Neuroendocrine regulation is regarded as an important factor underlying both attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and depression. Interestingly, animal studies convincingly show that stress during pregnancy results in offspring with increased anxiety and depressive behavior possibly by altered fetal development of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and alterations of regulatory and neurotransmitter systems in the brain.Reference Mulder, Robles de Medina and Huizink13, Reference Lazinski, Shea and Steiner14

Second, more than a quarter of HG pregnancies result in greater than 15% weight loss and symptoms persist until term in over 20% of pregnancies. This suggests that HG can be a form of prolonged starvation.Reference Fejzo, Poursharif and Korst9 Studies of the Dutch and Chinese famine reveal that among those exposed to famine during mid to late gestation, there is significantly lower birth weight, smaller head circumference and affective disorder. Those exposed to famine in the first half of pregnancy not only had significantly increased risk of obesity and coronary heart disease, but also reduced cognitive ability and significantly more schizophrenia spectrum disorders, congenital anomalies of the central nervous system and antisocial personality disorders. It is proposed that stunted brain development and abnormal programming of the HPA axis underlies these associations.Reference Painter, Roseboom and Bleker15–Reference Ross and Desai17

Third, severe cases of HG can lead to vitamin deficiency syndromes such as maternal Wernicke's encephalopathy caused by thiamine deficiency and fetal intracranial hemorrhage caused by vitamin K deficiency.Reference Chiossi, Neri, Cavazzuti, Basso and Facchinetti23, Reference Eventov-Friedman, Klinger and Shinwell24 Specific nutritional deficiencies in pregnancy such as deficits of folate and vitamin B12 have been linked to disruptions in myelination and inflammatory processes in infants and a greater risk of depression in adulthood.Reference Black25 In animal models, prenatal vitamin D deficiency is linked to adverse neuropsychiatric outcomes.Reference Harms, Eyles, McGrath, Mackay-Sim and Burne26

Although the cause of HG is unknown, hormone dysregulation is widely believed to be the most plausible explanation. Hormones, estrogen in particular, have been linked to development of the central nervous system in murine models.Reference Calza, Sogliano and Santoru27 In addition, abnormal maternal serum leptin levels are a marker of hyperemesis gravidarum,Reference Demir, Erel and Haberal28, Reference Aka, Atalay and Sayharman29 and neonatal hyperleptinemia is associated with an increased level of anxiety in adult rats.Reference Fraga-Marques, Moura and Claudio-Neto30 Thus, the results described herein may be the result of exposure to abnormal hormone levels during fetal development.

Lastly, HG can also lead to physical, psychological and a financial burden postpartum.Reference Fejzo, Poursharif and Korst9 Women with extreme weight loss due to HG were more likely to have longer recovery times, postpartum digestive problems, muscle pain, gall bladder dysfunction and post-traumatic stress disorder. A child with a behavioral disorder was reported by 9.3% of these women.Reference Fejzo, Poursharif and Korst9 It is possible that these conditions may have a negative effect on maternal–infant bonding which in turn may contribute to the behavioral abnormalities seen later in life. This theory is supported by rodent studies that show maternal care in the first week after birth results in epigenetic modification of genes expressed in the brain that shape neuroendocrine and behavioral stress responsivity throughout life.Reference Weaver31

Admittedly, there are multiple limitations to this study. There is an incomplete response rate for survey 2. The reason that approximately half of the participants that responded to the first survey did not respond to the second survey is unknown, but may have to do with a change in email address or the fact that the majority of women joined the study while they were currently pregnant and ill with HG, and the second survey was sent out at a later date when original participants may have been busy caring for infants. However, because both groups had similar response rates (and the non-responders were well-matched to the responders, data not shown), we do not believe this has an effect on the comparison between the two groups of responders. Other limitations to the study include its retrospective component and self-reporting of maternal HG status and sibling diagnoses, as well as the fact that our well-matched analysis and diagnosis comparison were conducted on two different pairs of groups. Therefore rates of diagnoses in each group should be treated with caution. However, the highly significantly increased risk identified in this study between cases and controls should reflect a valid comparison because the survey respondents were well matched for all factors studied and reported a similar occurrence of other outcomes not presented herein (i.e. autoimmune disorders and cancer). Therefore, we can think of no reason why one group would be more likely to have a greater reporting or recall bias than another with respect to the diagnoses reported here.

Recently, HG was linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes including smaller head circumference, and it was concluded that studies designed to assess the long-term consequences of HG should be given high priority.Reference Coetzee, Cormack, Sadler and Bloomfield32, Reference Roseboom, Ravelli, van der Post and Painter33 One of the strengths of this study comes from the long-standing collaboration with the Hyperemesis Education and Research Foundation that resulted in a unique opportunity to identify a large group of individuals whose mothers were affected by HG and the ability to collect long-term outcome data. In addition, the study design allowed for a significantly well-matched study population. Furthermore, by limiting the study to survey participants with HG, the study was able to control for potential confounding genetic factors contributing to HG that may also contribute to the outcome disorders.

In conclusion, a highly significant increase in neurobehavioral disorders in adults exposed to HG in utero was shown, which suggests that HG may be linked to life-long effects on the exposed fetus. The cause for this association is unknown, but may be due to maternal stress, malnutrition and vitamin deficiency, abnormal hormone levels during fetal development and/or maternal–infant bonding after birth. HG is an understudied and undertreated condition of pregnancy that can result in not only short-term maternal physical and mental health problems, but also potentially life-long consequences to the exposed fetus.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute of Health and Department of Health and Human Services.