Introduction

Much epidemiological research on the developmental origins of health and disease requires following study participants from early life to assess their growth and development. However, during adolescence, interpretation of a variety of measurements, such as those of body composition and mental health, requires knowledge of the participants’ stage of puberty at the time the assessments are made.

Accurate evaluation of puberty is key in the assessment of growth in young people. In a clinical setting, a physical examination of secondary sexual characteristics by a trained health professional (hereafter ‘clinical assessment’) is undertaken to document the stage of puberty,Reference Marshall and Tanner1,Reference Marshall and Tanner2 as changes in the timing and tempo of puberty may indicate delayed or precocious puberty, or adverse effects of an underlying disease or its treatment. The different aspects of the clinical assessment identify the degree to which the body has been exposed to different hormones: testosterone through its effect on pubic and axillary hair, and penile size, oestrogen through breast development and menarche, and gonadotrophins through testicular and ovarian volume. Clinical assessment is widely recognised as the gold standard method for assessing pubertal development.Reference Coleman and Coleman3–Reference Schmitz, Hovell and Nichols5 Traditionally attributed to Tanner (1962), this method uses a series of reference photographs accompanied by brief descriptions, which depict five stages of development of pubic hair growth for both sexes, and breast and external genitalia development, for girls and boys, respectively.Reference Tanner6 This resource is sometimes known as the sexual maturation scale (SMS) or sexual maturity rating (SMR).

In a research setting, it may be useful to understand the effect of exposures on the timing of puberty or the confounding effects of sex steroids on various outcomes. Study participants are often healthy, and the acceptability and practicality of a standard clinical pubertal assessment is less certain. The use of clinical assessments in cohorts and large-scale longitudinal studies can be challenging due to difficulties obtaining consent to a physical examination. Studies often rely on self-assessment methods or parental reporting, either as the main or a backup method when clinical assessment is declined. Self-assessment methods are also not without their challenges – for example, schools and parents may be concerned about the use of images depicting the development of secondary sexual characteristics.Reference Petersen, Crockett, Richards and Boxer7

There are few reviews of the different approaches to pubertal assessment in a research setting.Reference Coleman and Coleman3,Reference Dorn and Biro4,Reference Dorn, Dahl, Woodward and Biro8 In order to identify current methods for pubertal assessment and assess their appropriateness for population-based research, we combined a review of literature with the views of experts in the field, as well as the views of young people on acceptability of various methods.

Methods

Review of evidence

We sought studies that described and compared methods of pubertal assessment, specifically searching for those that reported validation of the methods. In December 2015, assisted by an information specialist, we searched the following online databases of abstracts: Medline, PsycInfo, Scopus, Sociological Abstracts, CINAHL and ERIC. Search results were imported into EndNote X7, and duplicates were removed. In addition, we consulted via email, and in person, clinical and epidemiology experts in the field for recommendations of relevant articles, and hand-searched key journals to identify further publications. Titles and abstracts were screened to determine the relevance of studies. Where these contained insufficient information, full articles were accessed. While we did not impose limits on publication dates or geographical location of studies, we excluded those articles where the full text was not available in English, due to a lack of funding for translation.

While we employed systematic review methodology in using a standardised form for data extraction and study quality assessment, we did not aim for an exhaustive review; methodology is often described briefly within research articles and search techniques do not necessarily identify all such articles, because of the indexing procedures. Consistent with the purpose of the review, which was to inform a workshop of experts, we gathered information on the use of the methods to the point of saturation, but did not attempt to include every study that has used the methods. Data were extracted from the included studies, using a standard proforma adapted for this review, by authors CS and IW, following which IW and HI double-checked half of the extracted records. The risk of bias of each included study was assessed using a quality assessment checklist adapted from guidance of best practice in systematic reviews.9 Results were collated in a table format and summarised in a narrative synthesis.

Expert opinion

The preliminary findings of the literature review were presented at a workshop at the MRC Lifecourse Epidemiology Unit, University of Southampton in September 2016, which was attended by 21 clinicians and epidemiologists from the Cohort and Longitudinal Studies Enhancement Resources (CLOSER) and Society for Social Medicine (SSM) networks. The workshop incorporated discussions of the approaches to pubertal assessment most suitable for research studies. The workshop was facilitated and chaired by two of the authors (JB and HI). Following a presentation of the review findings, presentations were also given by experts in specific approaches to pubertal assessment – clinical examination, growth assessment to infer pubertal stage, and hormonal approaches. Three break-out groups were then formed to consider two specific questions:

1. Which cross-sectional approach is most suitable to determine current pubertal stage?

2. Which pubertal features should we assess longitudinally (e.g. peak height velocity), and how should we measure them?

A snowballing technique was used to reach consensus. The discussions of the break-out groups were recorded on flip charts and fed back to all workshop participants. Further discussion took place within the group as a whole. JB took notes throughout the meeting and produced a report of the workshop, including a synopsis of each presentation and a summary of the discussion points that arose during the snowballing exercise. This draft report was circulated to all participants, and they were invited to comment. We also held additional discussions with experts in the field of adolescent medicine outside the workshop.

The views of young people

We consulted six boys aged 12–16 years and four girls aged 10–13 years, who were part of the University Hospital Southampton Children’s Panel, which is available for consultations relating to research and clinical care. Three female researchers spoke to the panellists in two sex-specific groups, gathering their views on the acceptability, preferences and barriers in relation to the following types of pubertal assessment: physical examination, self-assessment questionnaires, shoe and foot size assessments, and voice maturation assessment for boys. In addition, the boys were asked about the use of age at first nocturnal emission and the use of orchidometer to assess testicular size. The girls were asked about the use of age at menarche. We used examples of self-assessment questionnaires with line drawings representing Tanner stages, and let both the boys and the girls use Speechtest, an app that reports boys’ pubertal stage derived from hearing the participant counting backwards from 20 to 1.Reference Howard10

Results

We screened 11,935 abstracts and assessed 157 articles in detail. Of these, 38 were deemed relevant, with most articles reporting data comparing two or more methods of pubertal assessment. Not all studies were validation studies, since some did not include a comparison with the gold standard method of clinical assessment.

The majority of studies had methodological weaknesses. Most did not include justification of the sample size. Selection bias was an issue in a number of studies with highly selective samples consisting of, for example, children from particular socioeconomic backgrounds or those attending specialist clinics, where these substantially differed from the intended target populations. Many articles included insufficient details of the methods used. Eleven studies were conducted in the United States, nine in the United Kingdom, four in Sweden, two in Australia and two in Turkey, and one each from Chile, China, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, India, Iran, Japan, the Netherlands and South Africa. Review findings were grouped into five categories according to the pubertal assessment method.

Self-assessment

This was the largest group, with 17 relevant studies (Table 1). Most compared self-assessment using either the SMS or the pubertal development scale (PDS) against clinical assessment, with the PDS being an interview-based measure, consisting of questions about body changes and growth. Some studies used the photo version of the SMS, while othersReference Norris and Richter11,Reference Bonat, Pathomvanich, Keil, Field and Yanovski12 used a line drawing version,Reference Morris and Udry13 in order to increase acceptability of the images to young people.

Table 1. Description of studies using self-assessment methods

Agreement in Tanner stage between self-assessment and clinical assessment ranged from 43% to 81% of the sample. There was generally at least 84% agreement to within one pubertal stage for the SMS,Reference Schmitz, Hovell and Nichols5 and 85–100% for the PDS.Reference Schmitz, Hovell and Nichols5,Reference Brooks-Gunn, Warren, Rosso and Gargiulo14,Reference Hergenroeder, Hill, Wong, Sangi-Haghpeykar and Taylor15 Children earlier on in their development were reported to overestimate their stage of development, and children in the later stages were often found to underestimate this,Reference Brooks-Gunn, Warren, Rosso and Gargiulo14–Reference Desmangles, Lappe, Lipaczewski and Haynatzki17 although the opposite pattern was also observed.Reference Rasmussen, Wohlfahrt-Veje and Tefre de Renzy-Martin18 Girls tended to be more accurate in self-reporting than boys.Reference Bonat, Pathomvanich, Keil, Field and Yanovski12,Reference Morris and Udry13,Reference Carskadon and Acebo16 Certain aspects of development were self-reported with more accuracy than others; for example, self-assessment of pubic hair development tended to correlate well with clinical assessment for both sexes, whereas self-reported breast and external genitalia stages were more weakly correlated with clinical staging.Reference Bonat, Pathomvanich, Keil, Field and Yanovski12,Reference Hergenroeder, Hill, Wong, Sangi-Haghpeykar and Taylor15,Reference Norris and Richter19

Self-assessment using the SMS perfectly agreed with that based on the PDS in 56% of females and 39% of males,Reference Bond, Clements and Bertalli20 but agreement to within one Tanner stage was observed in 97% and 89%, respectively. Agreement between the two scales was also higher for 12–13-year-olds compared with 10–11-year-olds or 14–15-year-olds. However, when compared with clinical assessment, boys tended to rate themselves as more mature using the SMS drawings than using the PDS score, and girls tended to rate themselves as less mature. This may suggest that viewing the images of pubertal stage might encourage a socially desirable response among young people.Reference Bond, Clements and Bertalli20 Colour drawings used in a clinic setting yielded assessments by children that were close to those of raters. Assessments were less reliable, however, when children were overweight or obese,Reference Bonat, Pathomvanich, Keil, Field and Yanovski12,Reference Rabbani, Noorian and Fallah21,Reference Sun, Tao and Su22 although not all studies observed this.Reference Schmitz, Hovell and Nichols5,Reference Rabbani, Noorian and Fallah21

When children were asked to compare their development with their classmates in a ‘global question’, taking into account all aspects of puberty, there was high concordance with answers to the same question provided by clinical examiners, with 95% for boys and 93.5% for girls, although this was in a self-selected subsample of those who volunteered to undergo clinical examination.Reference Berg-Kelly and Erdes23 A continuous Tanner visual analogue scale, used in one study, was found to be somewhat less accurate than the SMS or PDS.Reference Schmitz, Hovell and Nichols5

Four studies explored the use of parental assessments of own child’s pubertal status. One of the studies used a single question as to whether a particular child had entered puberty; however, parents were asked the question one year after the children, which limits interpretation of these findings.Reference Lum, Bountziouka and Harding24 In another study, mothers of girls rated their daughters’ SMS-based Tanner stage higher than clinicians, but correlation with clinical assessment was 0.85, compared with 0.82 for self-assessment, indicating a potential for the use of this method.Reference Brooks-Gunn, Warren, Rosso and Gargiulo14 In the same study, mothers were more likely to overestimate breast staging at the beginning of breast development, but this was not found in relation to pubic hair.Reference Brooks-Gunn, Warren, Rosso and Gargiulo14 In a large study, mothers and children tended to underestimate pubertal state for girls and to overestimate it for boys.Reference Rasmussen, Wohlfahrt-Veje and Tefre de Renzy-Martin18 In another study, comparison of girls’ and mothers’ assessment of breast bud development using black-and-white Tanner photos with a clinical assessment a showed that self-assessments by the girls themselves had low concordance with breast bud assessment by a trained nutritionist.Reference Pereira, Garmendia and Gonzalez25 Maternal assessment of breast bud development among the leaner girls was more accurate than that by the girls themselves.

While the experts in our workshop saw clinical assessment as the gold standard, they recognised that acceptability among study participants was often low. They considered self-assessment to be the easiest approach within cohort studies and the only practical method, other than clinical assessment, in cross-sectional studies. They agreed, however, that it was a rather crude approach, given the likelihood that it would only accurately categorise pubertal status to within one Tanner stage.

Growth

We identified nine relevant studies of growth (Table 2). These generally focused on two parameters: age at height growth take-off, indicating the start of pubertal growth spurt, and age at peak height velocity, indicating the intensity of the pubertal growth spurt. Serial measurement of height was the most frequently reported approach, which can also help identify the pre-pubertal growth spurt.Reference Karlberg, Kwan, Gelander and Albertsson-Wikland26 Height velocity may correlate with secondary sexual characteristics, with one study demonstrating high correlation between height velocity and testicular volume.Reference Bundak, Darendeliler and Gunoz27

Table 2. Description of studies using growth methods

One approach to growth curve analysis is the SuperImposition by Translation And Rotation (SITAR) model.Reference Cole, Donaldson and Ben-Shlomo28 It takes into account characteristics that differ from one individual to the next – namely mean height, timing and rate of puberty. The SITAR method produces three measurements, representing differences in mean size and growth tempo, and a measure of growth velocity. The method also could be applied to growth in other parameters, such as foot length, and to the development of secondary sexual characteristics, such as breast, testicular and pubic hair development. A study of the Edinburgh Longitudinal Growth Study cohort that used the SITAR method showed high correlations in relation to pubertal timing between such markers as height, genital and pubic hair stages, and testicular volume, although correlations for the shared markers were significantly higher in the girls.Reference Cole, Pan and Butler29 This method recently has been applied to the height measurements from children in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) to enrich the dataset with measures that include age at peak growth velocity,Reference Frysz, Howe, Tobias and Paternoster30 a marker of pubertal timing. A rapid increase in foot length may correspond to the onset of puberty and Tanner stage 2 on clinical assessment.Reference Mitra, Samanta, Sarkar and Chatterjee31 Peak increase in shoe size has also been found to precede peak increase in sitting height,Reference Busscher, Kingma and Wapstra32 although the comparison was with data from an unrelated sample. Others compared mean age at increase in foot velocity with mean age at take-off in height, and found no significant difference between the two parameters.Reference Ford, Khoury and Biro33

The experts attending the workshop agreed that assessment of growth in height or foot size was a promising method, albeit that more evidence was required in relation to foot size. Growth assessment was thought to be feasible within cohort studies, provided measurements could take place with sufficient frequency, but by definition not suitable for cross-sectional studies.

Radiological methods of assessing the degree of maturation of the cervical vertebra, olecranon and digits have been proposed as pubertal assessment approaches. The Greulich and Pyle AtlasReference Greulich and Pyle34 and Tanner-Whitehouse III scoreReference Tanner, Whitehouse and Cameron35 can be used to assess skeletal age. A cervical-vertebral index indicates level of skeletal maturation,Reference Cericato, Bittencourt and Paranhos36 and radiological images of the olecranon correlate with those of the digits, yet there was no comparison with a reference standard in these studies.Reference Canavese, Charles and Dimeglio37,Reference Ozer, Kama and Ozer38 The experts agreed that radiological approaches were feasible in large-scale population-based studies, though required participants’ attendance at a clinic, limiting their use.

Hormonal assessment

Gonadotrophins and gonadal hormones

A number of articles discussed the potential for measurement of gonadotrophins as a means of assessing pubertal stage. At the onset of puberty, there is an increase in the overnight pulsatile release of luteinising hormone (LH), suggesting that early morning urinary LH might offer a way of determining Tanner stage in girls.Reference Apter, Bützow, Laughlin and Yen39,Reference Grumbach, Roth, Kaplan and Kelch40 Serum testosterone is aromatised to oestrogen in fat, and it is oestrogen that triggers growth hormone (GH) secretion in both sexes.Reference Søeborg, Frederiksen and Mouritsen41 Inhibin B is released from the ovary in pubertal girls and rises in early puberty, whereas inhibin A is slower to rise.Reference Sehested, Andersson, Müller and Skakkebaek42 For boys, testosterone rises throughout puberty, with the steepest rise seen between Tanner stages 3 and 4.

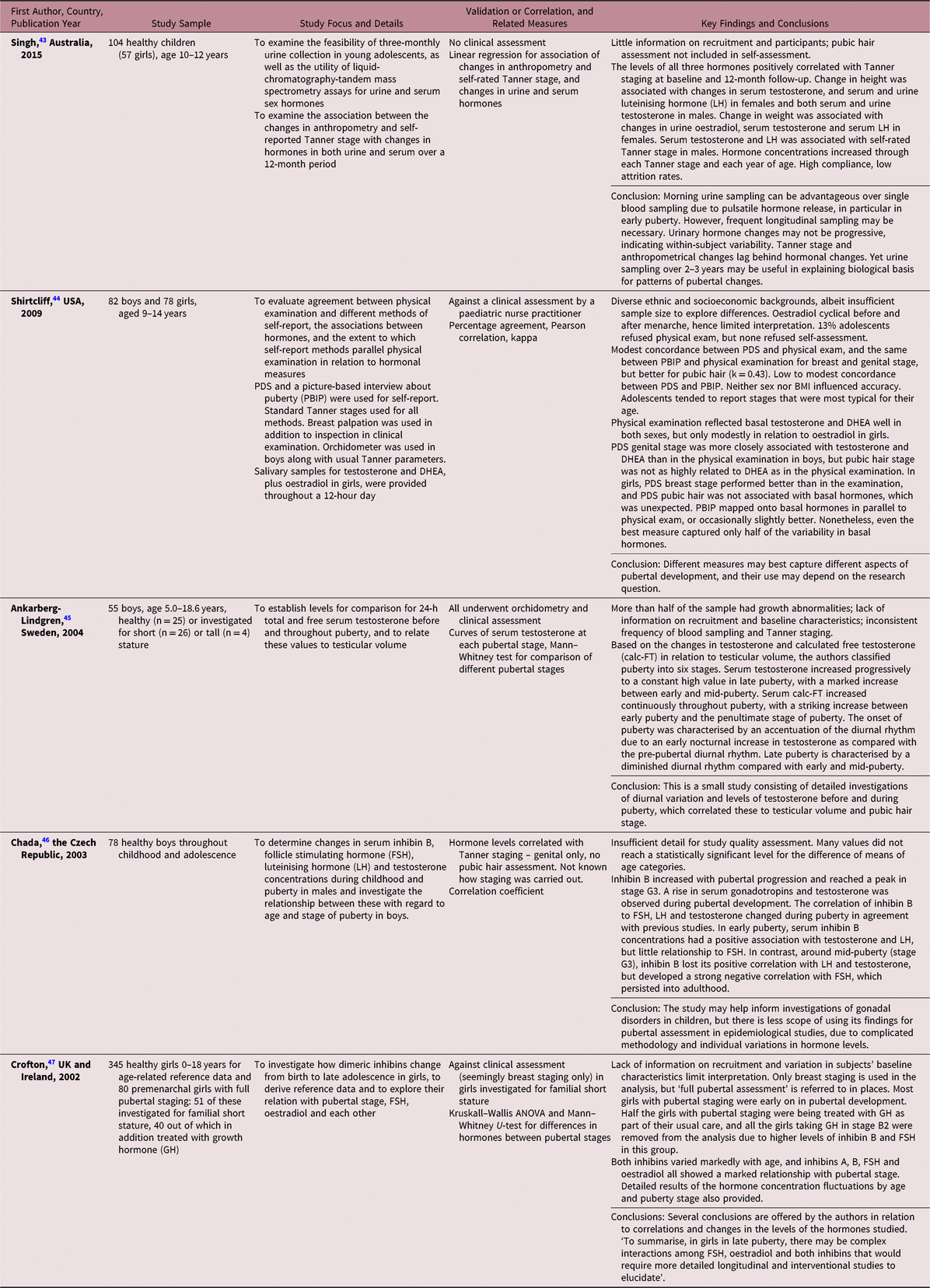

We identified five studies that incorporated both hormonal measurement and reference to pubertal staging (Table 3). In a study examining the correlation of three-monthly urinary oestradiol, testosterone and LH with self-reported SMS-based Tanner staging, the levels of all three hormones were correlated with the staging at baseline and 12 months later.Reference Singh, Balzer and Kelly43 In another study, staging based on physical examination reflected testosterone and DHEA levels in both sexes, but was only modestly related to oestradiol in girls.Reference Shirtcliff, Dahl and Pollak44 In boys, 24-hour testosterone levels in later puberty correlate reasonably well with testicular volume. Serum concentrations of testosterone increased progressively throughout puberty, with a marked increase occurring between early and mid-puberty. The onset of puberty was marked by accentuation of the diurnal rhythm of testosterone release due to increased release of testosterone at night.Reference Ankarberg-Lindgren and Norjavaara45 However, assays of urinary sex hormones both in boys and girls can be difficult to interpret due to within-person variability, and longitudinal sampling would be required to determine the hormonal changes associated with progression through pubertal stages.Reference Singh, Balzer and Kelly43,Reference Chada, Prusa and Bronsky46 It has been suggested that both inhibin A and B may have a potential as markers of pubertal development in boys and girls.Reference Chada, Prusa and Bronsky46,Reference Crofton, Evans and Groome47 However, progressive changes in their levels are not consistent enough to enable pubertal staging. On the whole, there are significant challenges to interpretation of such data due to the complexity of relationships between gonadotrophins, sex hormones and inhibins.Reference Chada, Prusa and Bronsky46,Reference Crofton, Evans and Groome47

Table 3. Description of studies using gonadotrophin or gonadal hormone methods

Leptin

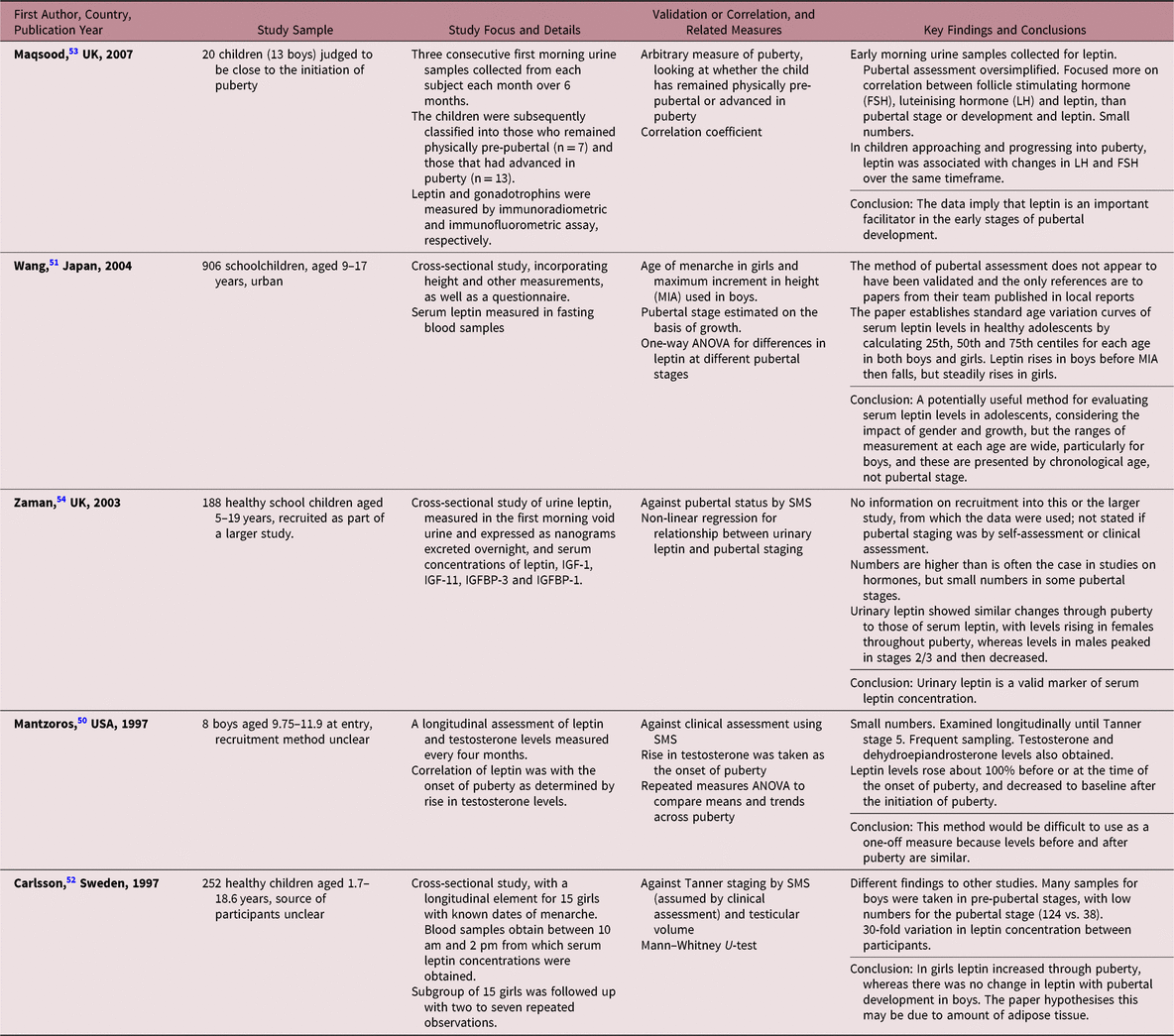

Leptin interacts with the reproductive axis at multiple sites with stimulatory effects on the hypothalamus and pituitary, and inhibitory action on the gonads.Reference Rockett, Lynch and Buck48 Leptin may affect the regulation of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and LH secretion during puberty.Reference Brann, Wade, Dhandapani, Mahesh and Buchanan49 There were five studies identified in this group (Table 4). One study reported an increase of 50% in serum leptin levels just before the onset of puberty, and a decrease to approximately baseline after the initiation of puberty.Reference Mantzoros, Flier and Rogol50 However, these findings were based on a small sample and should be treated with caution, given that another study showed that leptin levels varied widely among schoolchildren.Reference Wang, Morioka and Gowa51 Another study showed no correlation between serum leptin levels and age in boys, but a significant correlation in girls.Reference Carlsson, Ankarberg and Rosberg52

Table 4. Description of studies using leptin methods

Others have examined urinary leptin, demonstrating that monthly urinary leptin levels were higher in girls than boys over a period of six months.Reference Maqsood, Trueman and Whatmore53 Leptin was higher in children advanced in puberty, compared with children remaining pre-pubertal, but the measure of pubertal status was insufficiently described. Urine collection was a less invasive method for measuring leptin, compared with blood. In another study, urinary leptin showed day-to-day variability and correlated with serum leptin. Urinary leptin was similar in both sexes: in boys it increased significantly from Tanner stages 1 to 2, peaked in stage 3 and then declined for stages 4 and 5, while in girls there was a linear relationship between leptin levels and pubertal development.Reference Zaman, Hall and Gill54

The experts in the workshop regarded assay of sex hormones and leptin as an area of interest for assessment of pubertal stage, but the need for repeated measurements and the potential cost of assays were seen as barriers to their use in research.

Voice maturation assessment

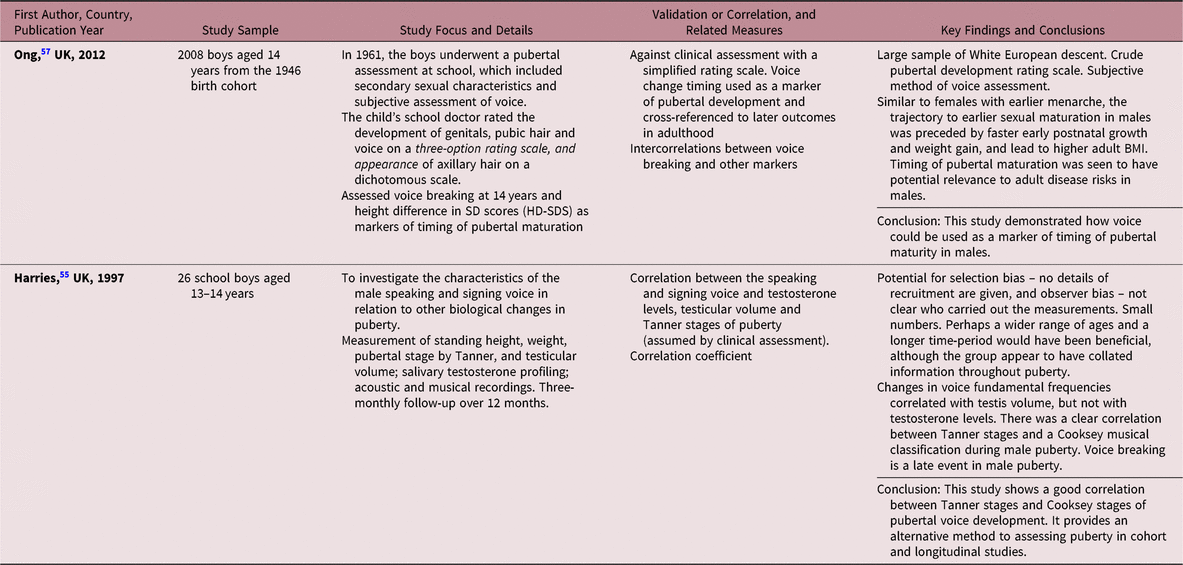

The maturation of the human voice is characterised by changes in pitch, loudness and a variety of tone qualities as the larynx grows in both sexes.Reference Harries, Walker, Williams, Hawkins and Hughes55 Voice breaking in boys usually occurs as a distinct event during late puberty, with a rapid drop in voice occurring during Tanner stages 3 and 4, usually around 12–15 years.Reference Hodges-Simeon, Gurven, Cardenas and Gaulin56,Reference Ong, Bann and Wills57 One study has shown that the timing of voice breaking could act as a non-invasive marker of pubertal maturation, with moderate correlation with other markers, such as genital development, and pubic and axillary hair growth (Table 5).Reference Ong, Bann and Wills57

Table 5. Description of studies using voice maturation methods

Cooksey classification of voice is based on a six-stage pattern of pubertal voice development derived from the singing range in boys, and this method has been validated previously.Reference Cooksey and Runfola58 A clear correlation was found between the Tanner stages and Cooksey classification of boys’ voices studied at three-month intervals. In addition, change in fundamental voice frequency was correlated with testicular volume, but not with serum testosterone levels.Reference Harries, Walker, Williams, Hawkins and Hughes55 The experts saw assessment of voice maturation as a promising method, and acknowledged the need for further research in this area.

The views of young people

The panel of young people expressed a preference for questionnaires, rather than clinical assessment. They were shown line drawings representing pubertal stages, and said that they preferred these to the photographs. They also preferred paper, rather than digital, versions of questionnaires, and thought that measurements of height and foot size were acceptable and likely to be so for their peers. All stated that the voice maturation assessment via a Speechtest app was acceptable, and boys were unlikely to exaggerate the depth of their voice, provided the assessment was done in private. The boys felt that they would find a question about their first nocturnal emissions embarrassing and that most would not be able to recall the timing of this correctly. They also stated that they would need to self-examine in private in order to estimate their testicular size if asked to use an orchidometer. The girls did not object to being asked about age at menarche if the person asking was a professional, but felt that their mothers might be more accurate in their reporting of this. Both boys and girls suggested that young people would be much more likely to consent to a clinical assessment if this were carried out by a professional of the same sex. They noted the importance of clear communication that the assessment was brief and did not require complete removal of their clothes.

Integration of review findings with the views of experts and young people

As a result of the literature review it was possible to draw a number of conclusions for each category of assessment. These are summarised in Table 6, alongside conclusions drawn from the discussions with experts and adolescents.

Table 6. Conclusions from the literature review and opinions of experts and adolescents

Discussion

This review examined the main pubertal assessment methods that are currently in use in research. Clinical assessment can be used across all Tanner stages, from the pre-pubertal stage to complete maturation, in contrast with some of the other methods, which may be more useful in relation to specific changes through puberty, such as the pubertal growth spurt, specific hormonal changes or voice maturation. Physical examination is non-invasive compared with blood sampling required for many hormonal methods, and less harmful than radiological methods. Clinical assessment can also be used in cross-sectional studies, in contrast to some other methods. However, our work suggests low acceptability of the clinical examination in a research setting. The young people suggested that good communication, and sex-matching of the assessor and participant, could help improve acceptability of the method. However, it is possible that even when an assessor of the same sex is not available, this may not necessarily lead to refusal.Reference Dorn59

The other methods considered in this review may have their place in pubertal assessment under different circumstances. The self-assessment approach may be suitable in studies where accuracy to within one Tanner stage is acceptable, in large-scale studies lacking resources required to facilitate clinical assessment or in settings where there may be strong objections to physical examination. Self-reporting may be affected by social desirability or accepted norms,Reference Norris and Richter11,Reference Brooks-Gunn, Warren, Rosso and Gargiulo14 and younger children may consider themselves older (and therefore, more developed) than they are, whereas older children might view themselves as younger, hoping for more development.Reference Desmangles, Lappe, Lipaczewski and Haynatzki17 Higher validity against the reference test of clinical assessment was observed when adolescents were allowed to self-examine before rating their own development, compared with self-recall from memory.Reference Rabbani, Noorian and Fallah21 Assessments of growth could be used in longitudinal studies, provided appropriately frequent measurements were feasible. The SITAR method in particular has the advantage over conventional approaches, in that it takes account of individual characteristics, such as mean height, timing and rate of puberty. The SITAR method could be applied to growth in other parameters, such as foot length, and to the development of secondary sexual characteristics. Assessing foot size is also a promising method. The absence of data on validity, along with the acceptability issues, means that radiological methods of pubertal assessment are unlikely to be appropriate for use in research studies. Measurements of gonadotrophins, gonadal hormones and leptin can provide a detailed picture of the biological changes taking place during puberty. High laboratory-associated costs, the need for repeat measurements and the invasiveness of blood tests are some of the current barriers to the wider use of the hormonal methods. Between- and within-person variability and the lack of evidence of validity against clinical assessment also limit the utility of the hormonal methods. Nonetheless, advances in this field might yield acceptable and reliable methods in the future. Assessment of voice maturation presents a convenient, albeit insufficiently validated, method.

Clinical assessment remains a subjective method, prone to measurement error and bias, particularly if not diligently conducted. The most frequently used black-and-white reference photographs are old, and depict Caucasian adolescents only. This has been highlighted previously,Reference Dorn and Biro4 and using more up-to-date resources would strengthen the method. Inter-rater variability could be improved by thorough training and rigorous protocols within research studies. It would be valuable to investigate the effect on rates of consent of improved communication and sex-matching of the clinical assessor and participant. More work is needed on the use of parental assessments. Studies of growth employing the SITAR method for parameters other than height would be of great value, in particular in relation to foot size. In addition, it would be helpful to determine whether there is scope for measuring foot growth using repeated self-administered questionnaires incorporating shoe size. There is a need for further research to assess the validity of hormonal assays as pubertal assessment methods, especially with regard to frequency of measurements and the use of less invasive methods, such as hair or urine sampling. Voice maturation assessment is another area where further evidence on validity of the method is needed, and development and evaluation of apps such as Speechtest might be useful, not least as they seemed acceptable to young people.

Previous reviews of methods for pubertal assessment agreed that clinical assessment constituted the gold standard method. Coleman and Coleman concluded that self- and parental assessment methods had lower validity than clinical assessment.Reference Coleman and Coleman3 An extensive review by Dorn et al. covered a range of objective and subjective methods and discussed important issues associated with each, proposing an argument that any methods could be used, provided they are appropriate for addressing the research questions in a study.Reference Dorn, Dahl, Woodward and Biro8 Dorn and Biro highlighted the difficulties obtaining consent for clinical assessment and the fact that self-assessment is prone to significant bias and insufficient agreement with clinical assessment, whereas hormonal methods do not lead to adequate Tanner staging.Reference Dorn and Biro4

One important consideration is that in research, accuracy implies proximity of results to the true value. Stages of puberty are artificial constructs, created in order to help to interpret the influence of the timing and tempo of puberty on health in adolescence and beyond. They are the best proxy we have for the ‘true value’ in pubertal development. Staging is an integral part of clinical assessment, which thus can be seen as the most accurate method, in contrast to, for example, growth, hormonal or voice methods, which sometimes attempt to arrive at Tanner stages indirectly. Depending on the method, within- and between-person variability in the parameters can affect the accuracy of estimating corresponding pubertal development stages. Furthermore, Tanner stages are well known and widely used by clinicians and researchers. It should therefore be borne in mind that the use of some other methods, such as the PDS, global question or a visual analogue method in self-assessment might complicate interpretation of study results and their use in comparative analysis and meta-analysis with studies that use Tanner staging.

In this review, we employed methodology that is conventionally used in systematic reviews, including extensive searches of the published literature, strengthened by input from an information specialist, careful screening of potentially relevant abstracts and papers, and detailed data extraction and quality assessment of included studies. This work adds to the existing reviews, incorporating the more recent studies and capturing methodologies not previously included, yet avoiding some of the areas already extensively discussed. We complemented our review with the opinions of experts, with whom the review findings were discussed. We found that there was considerable consistency between the views of the experts and overall conclusions emerging from the literature. Another strength of this work was the incorporation of the views of young people. This allowed triangulation with the review findings, which strengthened our interpretation.

Our review does not cover all research on approaches to pubertal assessment, given that our intention was to focus on methods that might be used in population-based research studies. We searched to saturation to identify relevant methods, but did not attempt an exhaustive review of all studies relating to each of the assessment methods. We did not search the grey literature or contact experts in order to identify relevant unpublished studies, hence publication bias is likely. Given that abstract screening was conducted by a single reviewer, it is possible that not all relevant published studies were identified. There were few validation studies. Descriptions of the methods in some articles lacked detail, presenting challenges for study quality assessment.

Conclusions

This review, complemented by the views of experts and young people, highlighted strengths and limitations of self-assessment methods in research studies, compared with the gold standard of clinical assessment of pubertal development. It has confirmed the barriers to the use of hormonal and radiological methods in this setting, and identified the need for further research into the validity of the promising growth assessment methods, such as foot size measurement, as well as voice maturation assessment. Improved assessment methods would enhance studies examining growth and development through adolescence.

Author ORCIDs

Inna Walker 0000-0002-8460-8130; Justin Davies 0000-0001-7560-6320; Hazel Inskip 0000-0001-8897-1749; Janis Baird 0000-0002-4039-4361

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Elizabeth Payne (Information Specialist, UK) for her assistance with literature searches, and to Tina Horsfall and Julia Hammond (MRC Lifecourse Epidemiology Unit, University of Southampton, UK) for their input in organising and running the University Hospital Southampton Children’s Panel discussions. Special thanks go to the young people for expressing their views on the methods. We are also grateful to Professor David Dunger (University of Cambridge, UK), Professor Tim Cole and Professor Russell Viner (both of University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, UK) for their advice on the topic and presentations at the expert workshop, as well as to the workshop participants for their contributions.

Financial Support

The review of evidence and the work with young people were supported by Cohort and Longitudinal Studies Enhancement Resources (CLOSER), UK (grant reference ES/K000357/1), and the workshop with experts was supported both by CLOSER and the Society for Social Medicine (SSM), UK. Hazel Inskip is supported by the UK Medical Research Council and the NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre, and her work receives funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreements no. 733206 (LifeCycle).

Conflicts of Interest

None.