Introduction

Despite these difficult economic times, there is a continued effort on the part of the world’s populations, whether they are in industrialized countries or those less developed, to improve the standard of living of their people. Although poverty remains a substantial issue in many areas, with improving living standards, and greater access to affordable, though not necessarily healthier nutrition, the problem of obesity and resultant complications are more frequently being recognized as global problems.1 The medical consequence of the increase in rates of obesity are the related problems of the metabolic syndrome; that is hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia and atherosclerotic vascular disease, etc (Table 1).2–Reference Einhorn, Reaven and Cobin5 These are the chronic medical conditions which in the coming decades will consume an ever increasing proportion of resources that less fortunate countries can ill afford. To date, however, much of the emphasis of the medical community has been on treatment and less on prevention. The perinatal period is certainly a time when a better understanding of the underlying physiology may provide a better insight into the factors which might prove amenable to prevention; not only for the women but also for her offspring as well. In this review, we will attempt to examine the underlying physiology and clinical factors relating to short and long-term impact of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and obesity on the woman and her offspring.

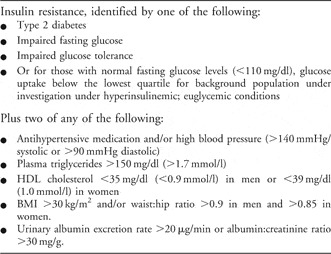

Table 1B WHO clinical criteria for metabolic syndromeReference Alberti and Zimmet3, 4

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; BMI, body mass index.

Table 1C AACE Clinical criteria for diagnosis of the insulin resistance syndromeReference Einhorn, Reaven and Cobin5

AACE, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Gestational diabetes

Pathophysiology

Gestational diabetes has been defined by the 4th International Workshop-Conference on GDM is: ‘carbohydrate intolerance of varying degrees of severity, with onset or first recognition during pregnancy’.Reference Metzger and Coustan6 However, in 2009 the International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Groups, an international consensus group of diabetologists and obstetricians, including the American Diabetes Association, recommended that high-risk women found to have diabetes at their initial visit, received a diagnosis of overt and not GDM using the criteria recommended in Table 2.7 In contrast to women with normal glucose tolerance, the underlying pathophysiology of GDM is present before pregnancy. Those destined to develop GDM exhibit decreased insulin sensitivity, before pregnancy, the latter likely to being overweight and obese.Reference Catalano, Huston, Amini and Kalhan8 These women also have an inadequate insulin response to maintain normoglycemia,Reference Buchanan9 much as one would find in individuals with type 2 diabetes. A very small number of cases of GDM may represent either the onset of type 1 diabetes or inherited genetic defects such as can be found in maturity onset diabetes of the young.Reference Catalano and Buchanan10

Table 2 Criteria for the diagnosis of overt diabetes in pregnant women at their initial prenatal visit

DCT, direct contact test; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

*In the absence of unequivocal hyperglycemia, criteria 1–3 should be confirmed by repeat testing.

Pregnancy is, and of itself, a condition of decreased insulin sensitivity with a 50%–60% decrease in insulin sensitivity and two to three fold increase in insulin response in women with normal glucose toleranceReference Catalano, Tyzbir, Roman, Amini and Sims11 (Figs 1 and 2). Hence, women at risk for GDM most often have decreased pregravid insulin sensitivity, including such problems as being overweight or obese. Because of their underlying subclinical decreased insulin sensitivity and β-cell dysfunction, the aforementioned metabolic stress of pregnancy makes clinically manifest the clinical disorder defined as GDM. Although, we primarily conceive of diabetes as a disorder of glucose metabolism, in women with GDM there are also reported abnormalities in lipid and amino acid metabolism, which may also affect the fetal growth.Reference Freinkel12 The decrease in insulin sensitivity during pregnancy have been associated with maternal cytokines, particularly circulating tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) concentrationsReference Kirwan, Hauguel-de Mouzon and Lepercq13 as well as the elevated free fatty acid concentrations.Reference Xiang, Peters and Trigo14 As insulin sensitivity significantly improves immediately post delivery,Reference Ryan, O’Sullivan and Skyler15 the placenta has been implicated to play a significant role in the alterations of maternal metabolism during human pregnancy.

Fig. 1 The longitudinal changes in insulin sensitivity women with gestational diabetes (GDM) and normal glucose tolerance (control). Pt, changes over time; Pg, differences between groups. (Adapted from Catalano, Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1999).

Fig. 2 The longitudinal changes in insulin response to an intravenous glucose challenge in women with gestational diabetes (GDM) and normal glucose tolerance (control). (a) first phase insulin response, (b) second phase insulin response. Pt, changes over time; Pg, difference between groups. (Adapted from Catalano, Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1999).

Maternal

Women, who develop GDM, are at increased risk for adverse perinatal outcomes. For example, women with GDM have a significantly greater risk of developing hypertensive disorders of pregnancy such as preeclampsia.Reference Joffe, Esterlitz and Levine16 This risk is analogous to the increased risk of chronic hypertensive disorders observed in insulin resistant individuals with type-2 diabetes. Recently concluded hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome (HAPO) study also reported an increase in the risk of primary cesarean delivery in women with elevated glucose concentrations. Of note, the HAPO study also confirmed that glucose concentrations less than those currently used to define GDM are associated with other adverse perinatal outcomes such as preeclampsia and birth injury.17 Hence, just as there has been an increase in the number of individuals classified as having either impaired fasting glucose (33.8%) or impaired glucose tolerance (15.4%),18 the number of women with GDM presently 5%–10% of the population19 may significantly increase pending results of recently held HAPO consensus conference. Consistent with the underlying pathophysiology of GDM, multiple studies have reported that 50%–60% of women with previously diagnosed GDM will develop type 2 diabetes in 10 yearsReference Kim, Newton and Knopp20 as well as other evidence of the metabolic syndrome. Thus pregnancy remains a metabolic stress test for women with underlying metabolic dysfunction.

Fetal

The infant of the women with GDM is often characterized as large or macrosomic. The term large for gestational age (LGA) is commonly defined as weight greater than the 90th percentile for gestational age, gender and racial group. Macrosomia is variously defined as birth weight greater than 4000 g to 4500 g. Infants of women with GDM, particularly if born LGA or macrosomic are at increased risk for short-term complications. During delivery because of their large size and difficulty in transit through the birth canal, shoulder dystocia, occasionally followed by Erb’s Palsy may occur.Reference Athukorala, Crowther and Willson21 Immediately after birth they are at increased risk for hypoglycemia because of the in utero hyperinsulinemia.Reference Alam, Raza, Sherali and Akhtor22 Other morbidities in the infant of the woman with GDM include hypocalcemia, hyperbilirubinemia and respiratory distress.Reference Cordero, Trener and Landon23

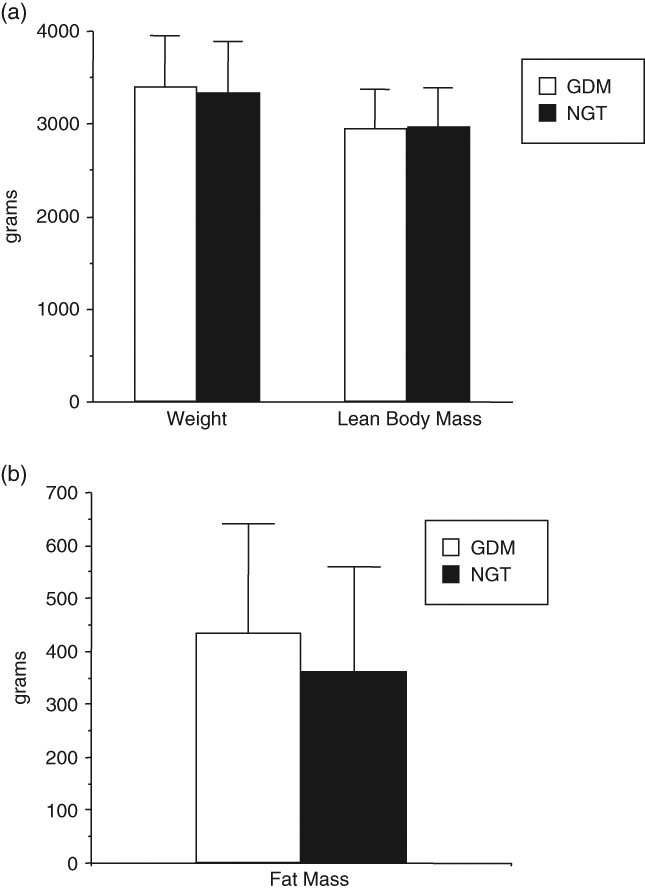

In assessing the body composition of infants of women with GDM, these neonates are heavier at birth because of increases in fat mass but not because of increases in lean body massReference Catalano, Thomas, Huston-Presley and Amini24 (Fig. 3). Again based on the results of the HAPO study, increasing maternal glucose concentrations, less than those currently used to define GDM, were also associated not only with an increase in birth weight but specifically and increase in neonatal adiposity.25 Of note, when examining the gene array profile of the placenta from obese GDM and normal glucose tolerant women, there is an increase in placental gene expression of enzymes related to lipid metabolism suggesting the potential of lipids as a nutrient sources of increased neonatal adiposity.Reference Radaelli, Varastehpour, Catalano and Hauguel-de Mouzon26 Those alterations in neonatal growth/adiposity may be one of the prime factors resulting in the long term complications observed in children of women with GDM.

Fig. 3 Birth weight, lean body mass and fat mass of full term neonates of women with gestational diabetes (GDM) n = 195 and normal glucose tolerant women (NGT), n = 220. Weight P = 0.26, lean body mass P = 0.74 and fat mass P = 0.0002. (Adapted from Catalano, Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2003).

Child

Children of women with GDM are at increased risk for long-term obesity and glucose intolerance. On the basis of early studies by Pettitt et al. children of Pima women with diabetes during pregnancy had significant increases in both diabetes and obesity.Reference Pettitt, Knowler, Baird and Bennett27 This risk persisted when the offspring of the women with diabetes where compared with their siblings born before the mother developed glucose intolerance.Reference Pettitt, Aleck and Baird28 These studies were later confirmed and expanded upon by Dabelea et al. also in a Pima Indian population.Reference Dabelea, Hanson and Lindsay29 In fact the strongest risk factor for diabetes in Pima Indian children is maternal diabetes in utero, independent of maternal obesity and birth weight.Reference Dabelea and Pettitt30–Reference Pettitt, Knowler and Bennett32 In a primarily Caucasian population, Boney et al. reported that not only did the large for gestational age children of the women with GDM had an increased risk of diabetes and obesity but that 50% of those children had evidence of the metabolic syndrome.Reference Boney, Verner, Tucker and Vohr33 In a recent multiethnic study, Hiller et al. reported that with increasing levels of hyperglycemia, particularly fasting hyperglycemia less than diagnostic of GDM, this was associated with an increased risk of childhood obesity.Reference Hillier, Pedula and Schmidt34

More recently, Clausen et al. reported that the risk of being overweight was doubled in the offspring, age 18–27 years, of women with diet trusted GDM or type 1 diabetes compared with a control group from the same background population. Furthermore, the risk of the metabolic syndrome in these same offspring was increased four-fold in comparison to the same background population.Reference Clausen, Mathiesen and Hansen35 In summary, the infant of the women with GDM has a significantly greater risk of being heavier at birth because of increased adiposity. These children are also at increased risk for the childhood obesity, glucose intolerance and associated metabolic dysregulation. However, based on clinical trials by CrowtherReference Crowther, Hillier and Moss36 and LandonReference Landon37 treatment of women with GDM during pregnancy can decrease some of the adverse neonatal outcomes. The potential improvement in long-term childhood outcomes awaits further study.

Maternal obesity

Pathophysiology

The WHO classification of obesity endorsed by Institute of Medicine (IOM),Reference Rasmussin and Yaktine38 based on maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index, (BMI, weight/height2). In pregnant women there is a strong correlation between maternal BMI and percent body fat in early pregnancy,Reference Sewell, Huston-Presley, Amini and Catalano39 much as there is in non-pregnant individuals. The correlation between maternal BMI and percent body fat is less robust, however, in later pregnancy because of the significant increases in total body water, that is the 40% increase in plasma volume and approximately 1 L of amniotic fluid. However, for clinical purposes maternal BMI has been accepted as a measure of obesity during pregnancy. There is a similar metabolic profile relationship between obese normoglycemic and lean normal glucose tolerant women as there is between women with GDM and those with normal glucose tolerance when matched for the degree of pre-pregnancy obesity. Relative to normal weight women, obese women with normal glucose tolerance, have decreased insulin sensitivity, both peripheral and hepatic as compared with normal weight women (Fig. 4). In addition, normoglycemic obese women have an increase in insulin response relative to normal weight women.Reference Catalano, Huston, Amini and Kalhan8 The increase in insulin response, however, may not be able to fully compensate for the increased insulin resistance, resulting in higher glucose concentrations in obese as compared with average weight pregnant women. Similar to what has been observed in GDM v. normal glucose tolerant BMI matched women, there is also an increase in lipid concentrations and decreased ability of insulin to suppress lipolysis in obese as compared with normal weight pregnant women in late gestation.

Fig. 4 The longitudinal changes in insulin sensitivity in average, overweight and obese women, before conception (pregravid) and in early (12–14 weeks) and late (34–36 weeks) gestation. Change over time, P = 0.0001. The obese women were less insulin sensitive than the average weight women (P = 0.001) and overweight women (P = 0.0004). (Adopted from BJOG, 2006). BMI indicates body mass index.

As noted previously there is an improvement in insulin sensitivity immediately post delivery.Reference Ryan, O’Sullivan and Skyler15 Similarly, when comparing the alterations in insulin sensitivity 1 year post delivery, there was a significant improvement in insulin sensitivity in normal weight women who returned to their pre-pregnancy weight.Reference Kirwan, Varastehpour and Jing40 In contrast, in obese women with normoglycemia in pregnancy who fail to return to their pre-pregnancy weight, these women have little or no change in their insulin sensitivity compared with their late pregnancy studies. Additionally, plasma TNF-α concentrations and the expression of TNF-α gene expression in skeletal muscle of these women remain higher 1 year post partum compared with normal weight controls.Reference Friedman, Kirwan, Jing, Presley and Catalano41 These data provide a plausible link between, obesity, inflammation and insulin resistance both during pregnancy and in non pregnant individuals as risk factors for glucose intolerance.

Maternal

Obese women have many of the perinatal problems present in women with GDM. This should not be surprising as maternal obesity is a significant risk factor for both GDM as well as type 2 diabetes. In early pregnancy obese women have an increased risk of spontaneous miscarriage.Reference Lashen, Fear and Sturdee42 Similar to what has been observed in women with preexisting glucose intolerance. In the fetuses of obese, non-diabetic women, there is also an increased risk of congenital anomalies; particularly neural tube and cardiac lesions.Reference Strothard, Tennant, Bill and Ramin43 Obese women also have an increased risk of the ‘metabolic syndrome of pregnancy’. They have an increased risk of glucose intolerance (GDM), hypertensive disorders (preeclampsia), hyperlipidemia and circulating inflammatory markers.Reference Catalano44 At delivery obese women are at greater risk of requiring cesarean delivery, both primary and failed trial of labor after a previous cesarean delivery. This increased risk of cesarean delivery may be related to fetal size (to be discussed later) or maternal soft tissue dystocia. The force of uterine contractions, however, appears to be similar to that estimated in non-obese women.Reference Buhimschi, Buhimschi, Malinow and Weiner45 Because of the increase in tissue disruption in obese women, there is an increase in the risk of post-cesarean wound infections in these women as compared with non-obese women. Additional post-partum risks include an increased risk of deep vein thrombophlebitis which may represent another manifestation of the ‘metabolic syndrome of pregnancy’.Reference Catalano44

Fetal

In parallel with the increase in maternal obesity in the past few decades, there has been an increase in birth weight reported in both European and North American populations.Reference Surkan, Hsieh, Johansson, Diceman and Cnattingius46, Reference Ananth and Wen47 Ananth and Wen have reported that there has been a 5%–10% increase in large for gestational age infants and an 11%–12% decrease in small for gestational age infants from the decade from 1985–1998. At birth, the term infant of obese women weighs on average of 150 g more than that of a normal weight woman. This increase in weight is primarily accounted for by an increase in fat mass and not lean body massReference Sewell, Huston-Presley, Super and Catalano48 as was reported in the infant of the woman with GDM (Fig. 5).Reference Catalano, Thomas, Huston-Presley and Amini24 Of interest, based on population based studiesReference Nohr, Vaeth and Baker49, Reference Chu, Callaghan, Bisch and D’Angelo50 obese women have less total weight gain in pregnancy as compared with average weight women, although their babies are heavier and fatter at birth. However, an increase in gestational weight gain in obese women is an additional risk factor related to fetal fat accretion.Reference Sewell, Huston-Presley, Super and Catalano48 In contrast to underweight or normal weight women where low or poor maternal weight gain in pregnancy is associated with small for gestational age (SGA) babies, in obese women poor weight gain in pregnancy is much less of a risk factor for a SGA infant.Reference Rasmussin and Yaktine38 Because of large size or macrosomia the infant of the obese women is also at risk for shoulder dystocia, although usually at higher birth weights than observed in the infant of the women with GDM.Reference Gottlieb and Galan51 This may relate to the central distribution of body fat in the infant of the woman with GDM.

Fig. 5 Birthweight, lean body mass and fat mass of full term neonates of average (BMI < 25) n-144 and overweight (BMI > 25) n = 76 women. Weight P = 0.051, lean body mass P = 0.22, fat mass P = 0.006. (Adapted from Sewell, Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2006).

The infant of the obese women is not only heavier at birth because of increased adiposity, but has evidence of increased insulin resistance using homeostasis model assessment estimates of insulin resistance compared with neonates of average weight women. Additionally, the cord blood leptin and interlukin-6 concentrations of the fetuses of obese women were significantly greater than the cord blood of the fetuses of the lean women. There was a strong correlation between fetal adiposity and insulin resistance.Reference Catalano, Presley, Minium and Hauguel-de Mouzon52 These data suggest that maternal obesity in and of itself poses a significant risk for the next generation with metabolic compromise already apparent at birth.

Child

Both maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and excessive weight gain during pregnancy have been related to increased obesity in children. There is now substantial evidence that the offspring of the obese women is at increased risk for childhood obesity. Whittaker reported that children born to obese women had a 2.5-fold increase increased the risk of obesity at 2–4 years of age based on Center for Disease Control and Prevention criteria compared with those children born to non-obese mothers.Reference Whitaker53 Similarly, Boney et al. reported that the children of obese women had a two-fold risk of not only obesity but the metabolic syndrome at an age of 11 years, compared with children of non-obese women.Reference Boney, Verner, Tucker and Vohr33 Lastly, Mingrone et al. in a follow-up study of young adults, noted that the offspring of obese women were more obese and insulin resistant as compared with the offspring of normal weight women at the time of their birth.Reference Mingrone, Manco and Mora54 Additionally, Oken et al. reported that increased gestational weight gain was associated with an increase in offspring BMI and skinfold measures at an age of 3 years. Women with adequate or excessive weight gain (IOM 1990 criteria) had a four-fold increase odd of having an overweight child (BMI > 95 percentile) using 2000 CDC reference data.Reference Oken, Taveras, Kleinman, Rich-Edwards and Gillman55

On the basis of our own long term follow-up studies of children of women with normal glucose tolerance and GDM during pregnancy, maternal obesity is a significant risk factor for childhood obesity and metabolic dysregulation. There was no significant difference in Center for Disease Control and Prevention weight percentiles or body composition between the children of the women with normal glucose tolerance in pregnancy and GDM at age nine. The strongest perinatal predictor for a child being in the upper tertile of obesity based on dual energy X-ray absorptometry methodology was maternal pregravid BMI odds ratio (OR) 5.45 (95% CI 1.62–18.4, P = 0.006). This relationship improved after adjusting for gender (OR 6.36; 95% CI 1.77–22.88, P = 0.004) and/or gender and if the mother had GDM (OR 7.75; 95% CI 1.51–37.74, P = 0.01). The strength of these relationships did not change when measures of neonatal adiposity were included in the analysis. Maternal pregravid obesity, independent of maternal glucose status was the strongest predictor of childhood obesity.Reference Catalano, Farrell and Thomas56

Although the review has been focused exclusively on the human model, there have been numerous animal studies explaining the mechanisms related to the observed physiologic changes. Van Assche et al. investigated the metabolic affects of a maternal cafeteria diet using a rat model. The diet induced obesity resulted in an increase in insulin resistance in the non-pregnant cafeteria fed rat, which was aggravated by pregnancy. The effect of obesity was greater then the effect of pregnancy on insulin resistance in this model. By using a similar murine model, Samuelsson et al. reported that diet-induced obesity in female mice leads to offspring obesity associated with adipocyte hypertrophy and altered mRNA expression of β-adrenoceptor 2 and 3, 11 BHSD-1 and PPAR-δ2. These alterations in adipocyte metabolism may very well play a role in offspring adiposity. The long-term effects including dysregulation of cardiovascular and metabolic function.Reference Samuelsson, Matthews and Argenton58 Lastly, Plagemann has reported that depending on critical periods of development, hormones such as insulin and leptin can act as ‘endogenous functional teratogens’. For example hyperinsulinemia may affect malprogramming of neuroendocrine systems, regulating appetite, body weight and energy expenditure.Reference Plagemann59

Summary

Maternal GDM and obesity share multiple metabolic abnormalities and may well represent a spectrum of maternal metabolic dysregulation. For the mother obesity and GDM increases the risk of the ‘metabolic syndrome of pregnancy’, that is an increased risk of hypertensive, lipid and coagulation disorders, which increases perinatal morbidity and mortality. The offspring of these women are also at increased risk for both neonatal morbidity and long-term sequela related to an abnormal in utero metabolic environment. Ideally life style modification of diet and activity to achieve normal weight before conception is the ideal goal to decrease the risk of these problems.Reference Rasmussin and Yaktine38 However, achieving recommended weight gain during pregnancy and avoiding excessive gestational weight gain as recently noted in the revised IOM guidelines may decrease perinatal morbidities such as maternal weight retention and hence reduced pregravid weight is subsequent pregnancies.Reference Rasmussin and Yaktine38 The perinatal period offers a window of opportunity to improve the short and long-term health of a woman and her offspring. If the goal is to prevent rather than treat chronic metabolic disease, then optimal care of women before and during pregnancy is a necessary component of health and well-being.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by NIH-NICHD HD22965, and Clinical Research Unit NCRR CTSA UL1 RR 024989.

Statement of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest regarding the contents of this manuscript.