Introduction

Breast cancer is a major health problem, since it is the leading cause of cancer deaths in women worldwide.Reference Smymiotis, Theodosopoulos and Marinis1 It is well known that the etiology of breast cancer is multifactorial and many risk factors can contribute to its development. Prevention is an effective strategy based on the adherence to healthy lifestyles.Reference Dieterich, Stubert, Reimer, Erickson and Berling2

Dietary components contribute to the etiology of 30–50% of all breast cancers.Reference Hilakivi-Clarke3, Reference Heitz, Baumgartner, Baumgartner and Boone4 However, it is important to consider that in order to permanently modify breast cancer risk, the dietary exposures may need to take place at times when the mammary tissue is undergoing extensive modeling. Mammary glands begin to develop during the prenatal life, but continue their remodeling during postnatal life, puberty, pregnancy and lactation, becoming more susceptible to carcinogenesis and making the influence of nutrition more important during those stages.Reference Hilakivi-Clarke3, Reference Musumeci, Castrogiovanni and Szychlinska5

Moreover, nutritional factors in early life have a strong influence on the development of pathologies of adult life, such as breast cancer.Reference Lillycrop and Burdge6, Reference Ferrini, Ghelfi, Mannucci and Titta7 This relationship occurs through the induction of epigenetic changes during the first years of childhood.Reference Verduci, Banderali and Barberi8 Those changes may be maintained over time, generating modifications in the structure of the mammary gland that make it more susceptible to cancer development.Reference Lillycrop and Burdge6 Breast milk is considered a type of food that acts as an epigenetic modulator of gene expression of the milk receiver.Reference Melnik and Schmitz9, Reference Irmak, Oztas and Oztas10 Taken together, all these evidences suggest that consuming breastmilk during the postnatal life may prevent the risk of developing breast cancer during adulthood.

Only a few epidemiological studiesReference Freudenheim, Marshall and Graham11–Reference Weiss, Potischman and Brinton14 show that breastfeeding may reduce the risk in the infant of developing premenopausal breast cancer, while the results in postmenopausal women are inconsistent.Reference Freudenheim, Marshall and Graham11, Reference Titus-Ernstoff, Egan and Newcomb13, Reference Potischman and Troisi15 The mechanisms by which breastfeeding prevents breast carcinogenesis in adult life have not been fully investigated.

In this report we studied the influence of a differential intake of milk during lactation on the development of mammary cancer in adult life in rats, and the possible mechanisms involved in tumor biology. We hypothesized that reducing the size of the litter, the pups have more access to the maternal milk, and consequently, a reduced risk to develop mammary cancer during adulthood. To test that hypothesis, we compared mammary carcinogenesis in adult rats grown in litters of 3, 8 or 12 pups per dam. We found interesting differences in the incidence, latency and the biology of mammary tumors and we investigated the expression of some proteins related to mitosis or apoptosis in the tumor cells.

Materials and methods

Postnatal litter size adjustment

Female Sprague-Dawley rats bred in our laboratory were used. The animals were kept in a light (lights on 6 am to 8 pm) and temperature (22–24°C) controlled room. One-day-old female pups (n = 51) born on the same day were distributed at random in litters of different sizes: three (L3), eight (L8) or 12 (L12) pups per dam, to induce a differential consumption of maternal milk. The size of the litters was chosen in accordance with previous studies.Reference Velkoska, Cole and Morris16, Reference Chen, Simar, Lambert, Mercier and Morris17 It has been previously demonstrated that fostering of one-day-old pups of the Sprague-Dawley strain does not lead to any adverse effect.Reference Barbazanges, Vallée and Mayo18 Body weight of pups was monitored every 3 days.

At day 21, the litters were weaned and fed with rat chow (Cargill, Argentina) and tap water ad libitum until the end of the experiment. They were housed in cages containing approximately six rats from the same group per cage. Body weight was measured once a week in order to elaborate their growth curves. In this way we obtained three groups of rats’ growth with different levels of lactation: L3 (n = 14), L8 (n = 23) and L12 (n = 14).

Induction of mammary tumors

At the age of 55 days all rats were treated per os with a single dose (15 mg/rat) of 7,12-dimethylbenzanthracene (DMBA, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) by an intragastric probe, 3 h after food and water deprivation to ensure a complete absorption of the drug. DMBA has been extensively used at that dose to study mammary carcinogenesis.Reference Barros, Muranaka and Mori19–Reference Russo and Russo21 The animals were palpated twice a week. Latency, incidence and progression of tumors were determined in all groups.

Latency, incidence and progression of tumors

The latency was considered as the time between DMBA administration and the appearance of the first palpable tumor. Incidence was calculated as the percentage of rats that had tumors within the study period with respect to the total number of rats per group. We used a caliper to measure the major (DM) and minor (dm) diameters of the tumors twice a week and calculated the tumor volume (TV) as TV = dm2 × DM/2. Tumor progression was assessed estimating tumor growth rate (GR) as GR = TV/(day of sacrifice-day of appearance of first tumor).

Sample collection

All the animals were decapitated between 10 am and 12 noon on the day of diestrus when the tumors reached a volume ⩾1000 mm3 or at the end of the experiment on day 250 if they did not develop any mammary tumor.Reference Sasso, Santiano and Lopez-Fontana22 When more than one tumor developed in a single rat, the volume limit of 1000 mm3 was considered for the first tumor reaching that value. Immediately after decapitation, intra-abdominal fat was removed, weighed and expressed as a percentage of total body weight. A piece of each tumor was removed for histopathological and immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis.

Tumor histology

Small pieces of each tumor were processed for histopathologic studies by fixing in buffered formalin, dehydrating in ethanol and embedding in paraffin wax. Sections (3–5 μm) were cut with a Hyrax M 25 microtome and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to classify tumors according to the published criteria.Reference Lopez-Fontana, Sasso and Maselli23, Reference Russo and Russo24 Images were captured with an Eclipse E200 microscope coupled to a CCD camera with 5.0 M resolution, and were analyzed with Micrometrics SE Premium (both from Nikon Corp., Japan) under magnification of 100×, 400× and 600×.

Apoptotic and mitotic indexes

Ten fields of histological sections of each tumor (6–19 tumors/group) stained with H&E were observed with a magnification of 400×. The counting of mitotic and apoptotic figures was performed in double-blind by two independent observers, avoiding fields with necrosis, inflammation or tissue folds. Mitotic and apoptotic indexes were calculated from this count. The mitosis/apoptosis ratio (M/A ratio) was calculated by dividing the mitotic index by the apoptotic index from each tumor.

Immunohistochemistry

Serial sections (3–5 μm) were mounted onto 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (Sigma-Aldrich, Argentina)-coated slides for subsequent IHC analysis. An antigen retrieval protocol using heat to unmask the antigens was used (30 min in citrate buffer, 0.01 M, pH 6.0). Tissue sections of 6–19 tumors/group were incubated overnight at 4°C in humidity chambers with the primary antibodies anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA, Dako Cytomation, Denmark) and anti-Ki67 (Abcam, USA). A commercial kit to detect mouse antibody was used (Dako EnVision system, horseradish peroxidase, diaminobenzidine; Dako, USA). Slides were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin to reveal the nuclei, examined and photographed. The percentage of positive nuclei was obtained based on an average of 700 cells counted per sample, at 400× magnification. We used a scoring system reported previously.Reference Gago, Tello, Diblasi and Ciocca25 Briefly, we used an intensity score 0 = no staining, 1 = nuclear staining of <10% of tumor cells, 2 = staining between 11 and 33% of tumor cells, 3 = staining between 34 and 65% of tumor cells, 4 = staining of >66% of tumor cells. These scores were obtained by two independent observers blinded regarding the experimental group, and a few conflicting scores were resolved by consensus.

Western blotting

Total proteins were extracted from tumors, and Western blot was performed as described previously.Reference Sasso, Santiano and Lopez-Fontana22, Reference Lopez-Fontana, Sasso and Maselli23 A quantity of 50 μg of protein were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and electrotransferred to Immun-Blot® polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, USA) overnight at 4°C. After rinsing and blocking with bovine serum albumin of 0.5%, the membranes were incubated overnight with corresponding primary antibodies anti-Bcl-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., USA); anti-caspase 8 and anti-Bax (Abcam, USA); anti-cleaved caspase 9 (Cell Signaling Technology Inc., USA); Bid (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., USA) and then, with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., USA). Protein expression was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham ECL™, GE Healthcare, Argentina) using a ChemiDoc XRS+ System with Image Lab Software from Bio-Rad to detect specific bands that were quantified by densitometry using FIJI Image processing package.Reference Schindelin, Arganda-Carreras, Frise and Kaynig26 The membranes were probed with ß-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., USA) as loading and transfer control.

Estimation of milk intake in pups from different sizes of litters

The average increase in weight of the litter during a lactation period serves as an estimate of the amount of milk secreted during the secretion interval. To determinate this, litters of 3, 8 or 12 pups per dam (n = 5 mothers in each group) were separated from their mothers at 7 am on days 10, 11 and 12 of lactation, during 4 h (separation interval). Before being returned to the mothers, the pups were weighed individually. Then they were allowed to suck for 60 min. At the end of that suckling time, the pups were weighed again. The results were expressed as the average of the individual weight increases per litter.Reference Morag, Popliker and Yagil27 Data from days 10 and 11 were discarded assuming that dams and pups were adapting to the disruption of their normal suckling routine during that period, to minimize any stress during the experiment on day 12 when the data were actually recorded.

Triglycerides, proteins and lactose in milk

Milk was obtained on day 14 of lactation from five mothers per group with litters of 3, 8 or 12 pups per dam. Pups were separated from their mothers at 7 am; 4 h later, the dams were lightly anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), administered with an intraperitoneal injection of 1 IU of oxytocin and milk was extracted by gentle pressing the nipples as previously described.Reference Hapon, Varas, Giménez and Jahn28 About 0.5 ml of milk was obtained from each rat and kept frozen in microvials until determinations. Concentrations of triglycerides (TGs), protein and lactose were determined by the end-point colorimetric method, in a Roche’s clinical chemistry analyzer Cobas c311.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.01 software (GraphPad Software Inc., USA). Differences in the variables between the three studied groups (L3, L8 and L12) were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA I) or the Kruskal–Wallis test, depending on the normality of the variables as evaluated by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Post hoc comparisons were performed by Bonferroni’s test or Dunn’s multiple comparison test. The means of the body weight gain of the litters in function of time were compared using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA II). Post hoc comparisons were executed by Bonferroni’s test. Tumor incidence was analyzed by Fisher’s test. Differences were considered significant when the probability was 5% or less. Divergence in the survival curves were estimated according to the limit product of Kaplan–Meier.

Results

Body weight and the validation of the experimental model

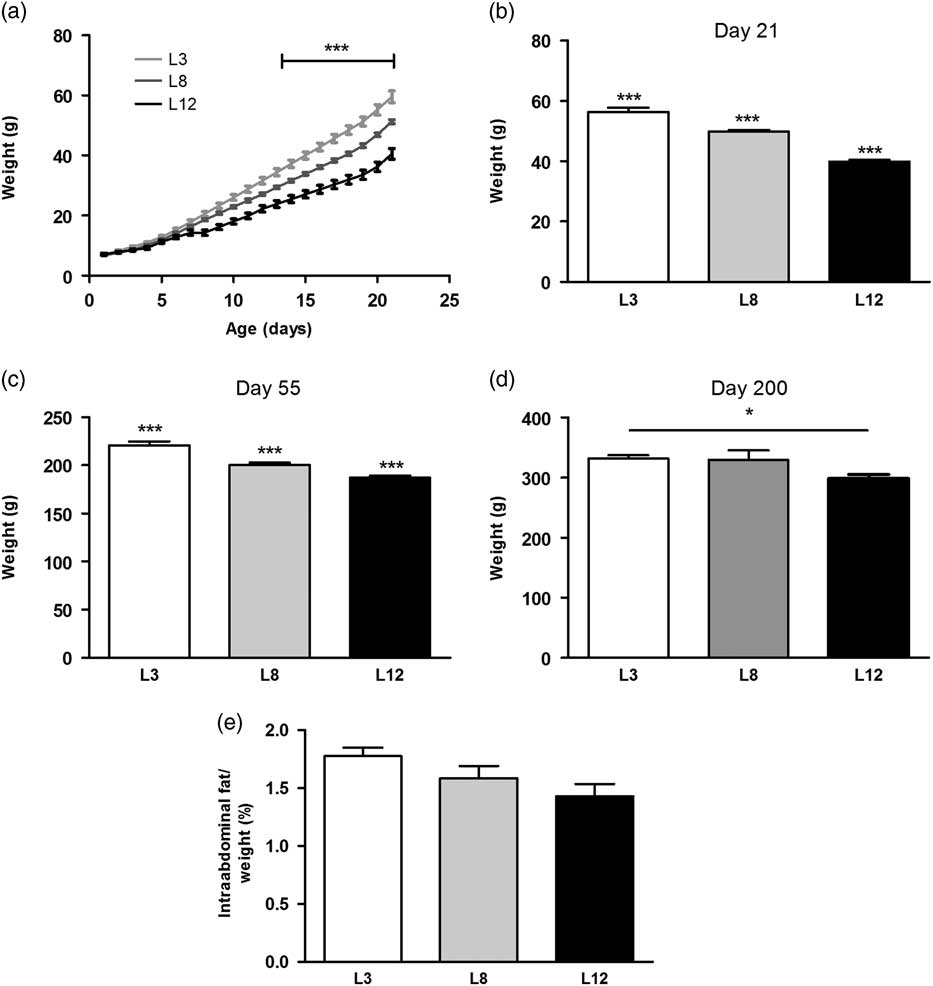

The growth curves of the animals showed a significant increase in weight (P <0.001) in L3 with respect to L8 and L12 from day 13 of lactation onward. We also observed, from the same day, an increase in weight (P <0.001) in L8 compared to L12 (Fig. 1a). When the offspring were weaned, on day 21 of life, the difference in weight was significant between L3, L8 and L12 (P <0.001, Fig. 1b). Clearly, this divergence was due to variations in the consumption of maternal milk between litters, corroborating our animal model. The difference in body weight among the three groups of animals was still maintained at day 55 of life, day of DMBA administration (P <0.001, Fig. 1c). On day 200 of life, median of the time of decapitation, a higher weight was still observed in L3 with respect to L12 (P <0.05, Fig. 1d). The abdominal fat mass weighed on day 55 was similar in the three groups (Fig. 1e). The mass of abdominal fat expressed as a percentage of body weight has previously been used as a measure of body composition in rats.Reference Vazquez-Prieto, Renna and Diez29

Fig. 1 Variations of the body weight due to the differential consumption of milk. (a) The variations in weight between the three groups can be observed from day 13 of life onward (***P <0.001). (b) At day 21 of life L3 maintained a significantly higher body weight with respect to L8 and L12 (***P <0.001). In turn, L8 also had bigger average weight compared to L12 (***P <0.001). (c) The differences in body weight observed on plot b were maintained until day 55 of life (***P <0.001 with respect to the other groups). (d) L3 maintained a greater weight than L12 at day 200 of life, considered the time of sacrifice of most animals (*P <0.05). (e) No significant differences were found in the abdominal fat mass between the three groups. Values represent mean ± s.e.m. of 14–23 animals/group. Comparisons shown in a, were performed by ANOVA II and Bonferroni’s test. Values shown in b, c, d and e were compared by ANOVA I and Bonferroni’s test. L3, litter of three pups per mother; L8, litter of eight pups per mother; L12, litter of 12 pups per mother.

Milk intake

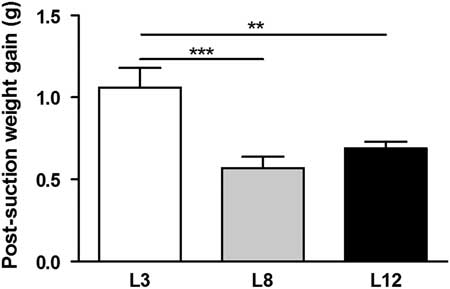

The results of the separation-suction experiment on day 12 of lactation show that the average gain of weight of the pups was higher in L3 compared to L8 (P <0.001) and L12 (P <0.01, Fig. 2). These results indicate a higher intake of milk per pup in the mothers who breastfeed three offspring compared to those who breastfeed eight and 12 pups.

Fig. 2 Milk intake. The animals fed in litters of three pups per mother (L3) showed a weight gain higher than those fed in litter of eight (L8; ***P <0.001) and 12 (L12 **P <0.01) during the suction separation procedure on day 12 of life. The values represent the mean ± s.e.m. of 15–60 animals/group. The comparisons were made using ANOVA I and Bonferroni test as post hoc.

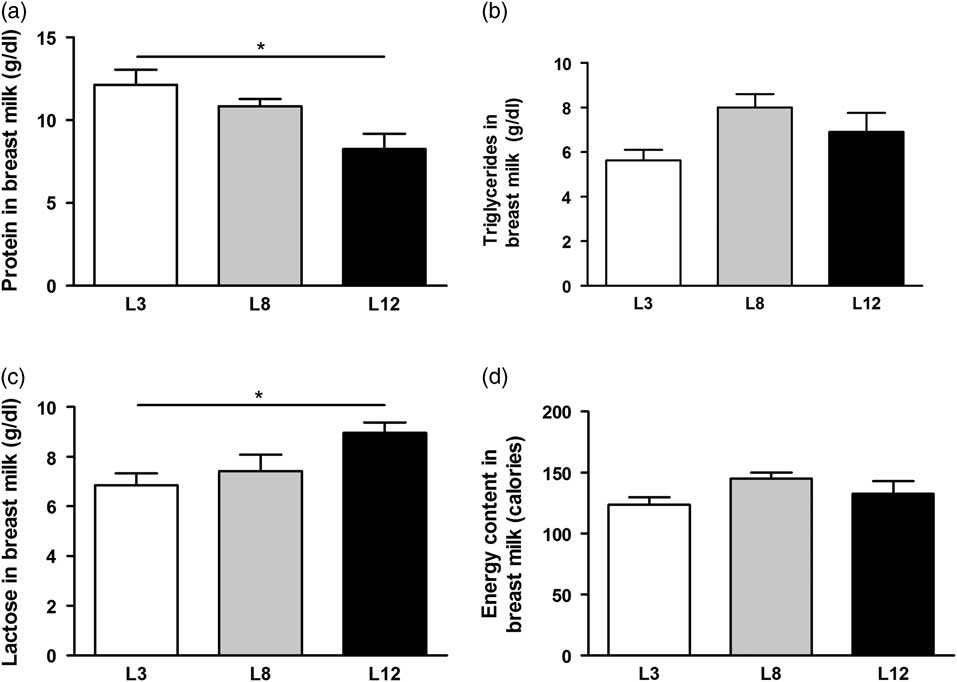

Composition of macronutrients of breast milk

The nutritional composition of macronutrients in breast milk was determined on day 14 of lactation (Fig. 3). The content of total proteins was higher (P <0.05) in the mothers with reduced litters (L3) compared with the milk produced by mothers with larger litters (L12). Conversely, lactose content of breast milk is higher in mothers with litters of 12 pups (P <0.05) compared to mothers with litters of three pups. No differences were observed in the content of TGs and total calories between the milk of the different mothers.

Fig. 3 Composition of macronutrients in breast milk. (a) The total protein content of milk is significantly higher in mothers L3 v. L12 (*P <0.05). (b) No differences were observed in the TGs content of the milk between the different mothers. (c) Lactose concentration of milk is higher in L12 mothers with respect to L3 (*P <0.05). (d) The total calorie content of milk is similar in all mothers, regardless of the number of pups that nursed. The values were obtained from five samples per group. The comparisons were made using ANOVA I and Bonferroni test as post hoc.

Differential milk intake does not affect tumor histopathology

Table 1 shows the histopathological characteristics of mammary tumors developed in the three experimental groups. Tumors were predominantly ductal. The inflammatory response and tumor fibrosis were limited in L3 and L8, and moderate in L12. In contrast, necrosis was limited in L8 and L12, and moderate in L3.

Table 1 Summary of principal characteristics of tumors developed in the DMBA-treated rats

L3, litter of three pups per mother; L8, litter of eight pups per mother; L12, litter of 12 pups per mother.

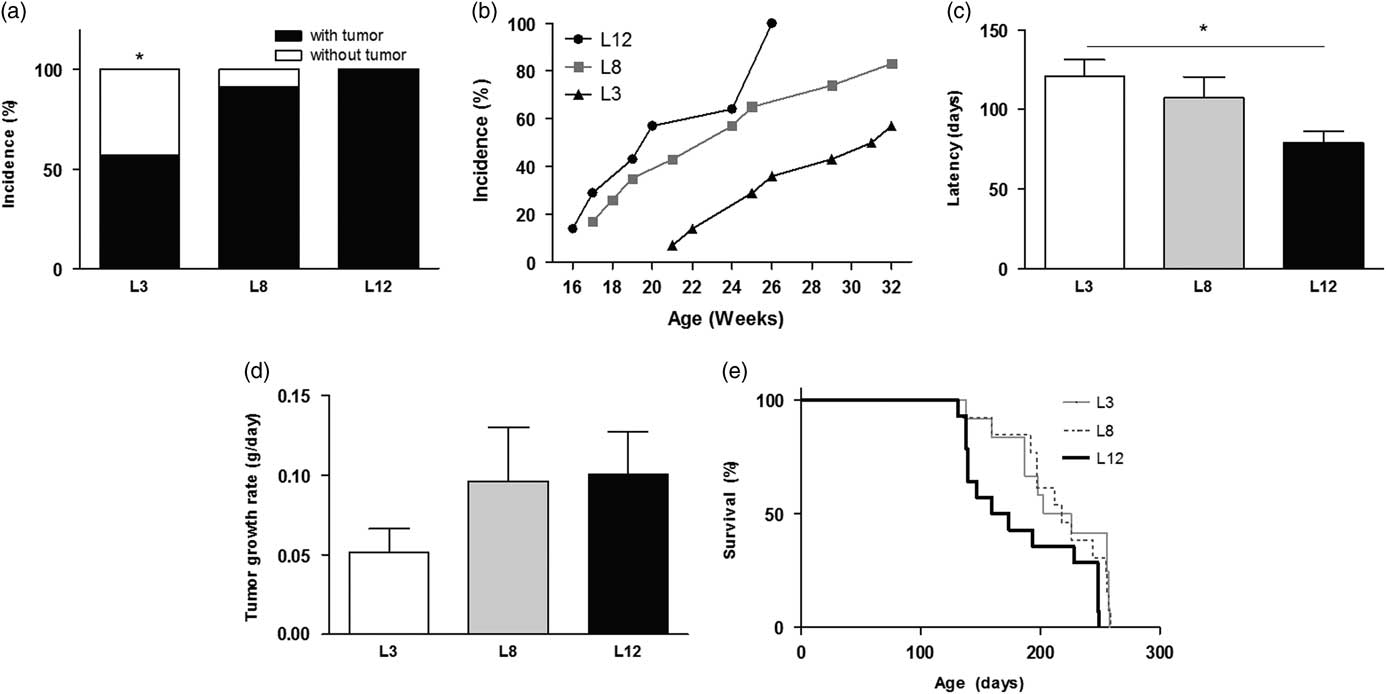

High milk intake decreases tumor incidence

Animals that maintained high milk intake (L3) had lower mammary cancer incidence than the other groups, calculated both overall and weekly (P <0.05, Fig. 4a and 4b). Accordingly, they also showed longer tumor latency compared to L12 (P <0.05, Fig. 4c). The GR of the tumor, expressed as grams per day, was similar between the three groups, although a trend to faster tumor growth was observed in the animals that maintained lower milk consumption (L12, Fig. 4d). The L3 group presented a marked tendency (P = 0.0592) to have a longer survival free of mammary tumors smaller than 1000 mm3, compared to those who maintained lower milk consumption (L12, Fig. 4e). This tendency reached significance when compared only L3 v. L12 (P <0.05) due to the dispersion of data in the L8 group.

Fig. 4 High milk intake affects mammary carcinogenesis. (a) L3 had a lower tumor incidence than the other groups (*P <0.05). (b) Weekly tumor incidence. (c) The latency of onset of tumors was longer in L3 than in L12 (*P <0.05). (d) No differences were found between the groups in the rate of tumor growth. (e) Survival curves show a tendency (P = 0.0592) to have longer survival free of tumors sized <1000 mm3 in L3 than in L12. Values represent mean ± s.e.m. of each group. Comparisons in latency and tumor growth were performed by ANOVA I and Bonferroni’s test as post hoc. Incidence was expressed as percentages and compared by Fisher’s test. Survival curves were compared according to the limit product of Kaplan–Meier. L3, litter of three pups per mother; L8, litter of eight pups per mother; L12, litter of 12 pups per mother.

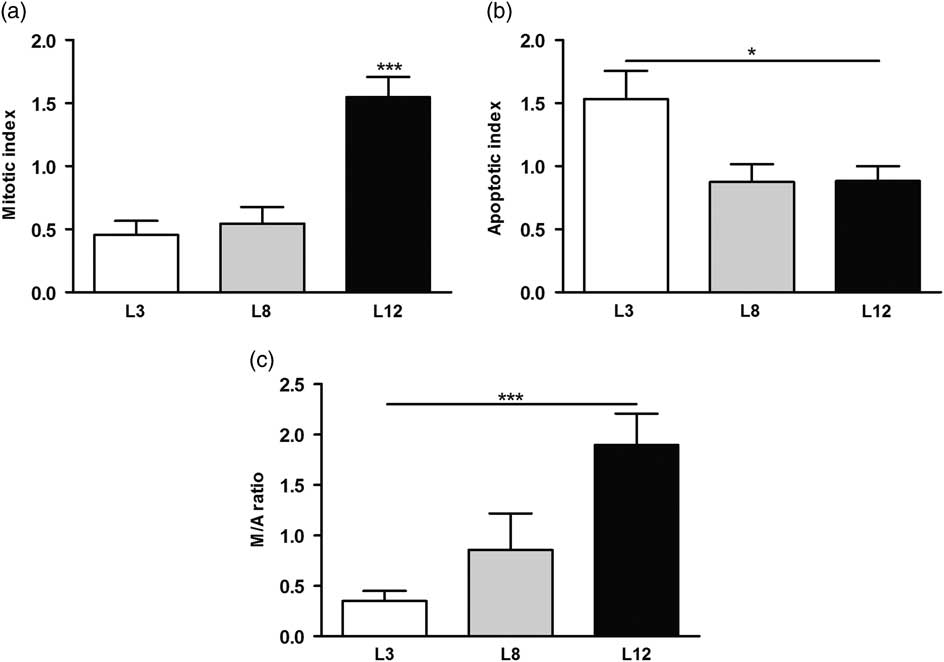

High intake of milk increases apoptosis and decreases mitosis in the tumors

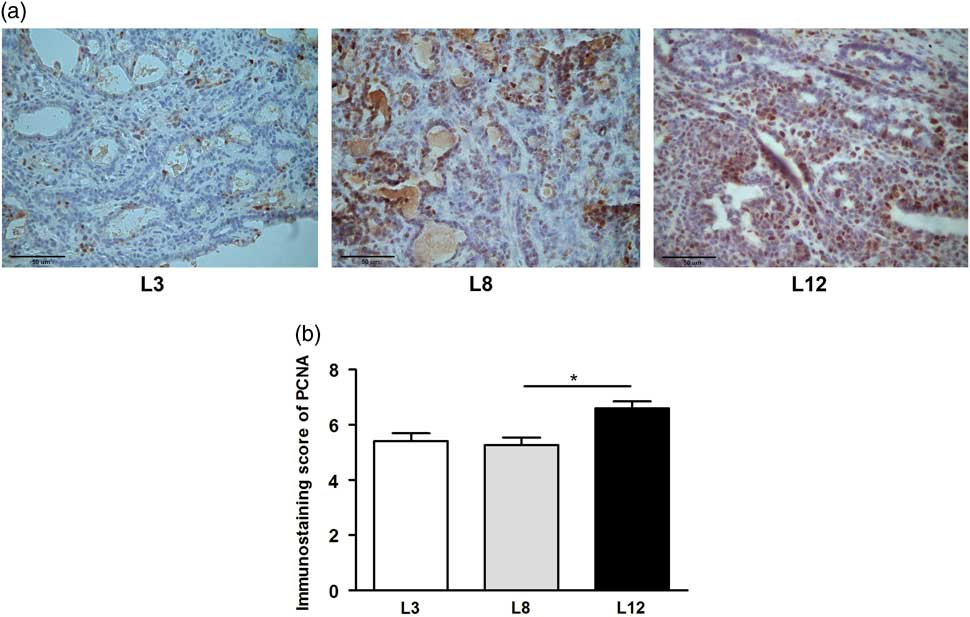

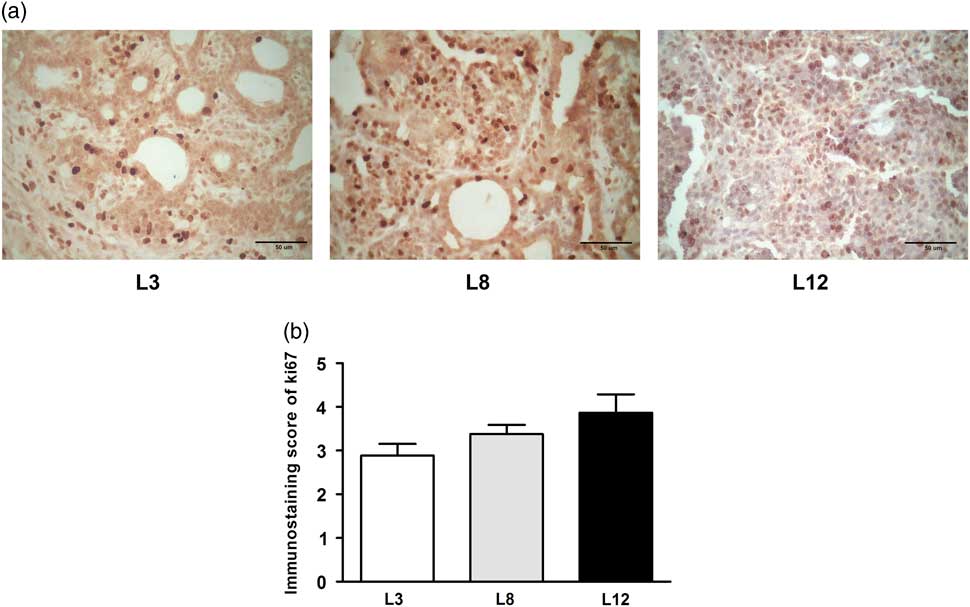

We performed a microscopic analysis of mitosis and apoptosis to assess the effect of differential lactation on the development of the tumors. The mitotic index was significantly augmented in tumors of L12 rats compared with L3 and L8 (P <0.001, Fig. 5a), while the apoptotic index was augmented in tumors of L3 v. L12 (P <0.05, Fig. 5b). To investigate whether the balance between mitosis and apoptosis influences tumor development, we calculated the mitotic/apoptotic ratio. This parameter was significantly higher in L12 when compared to L3 (P <0.001, Fig. 5c). We additionally evaluated mitosis by IHC of PCNA and Ki67 in the tumors, in order to validate the results obtained by counting mitotic figures. Coincidentally, we observed an increased expression of PCNA (P <0.05, Fig. 6) and Ki67 (Fig. 7) in tumors of the L12.

Fig. 5 High milk intake increases apoptosis and decreases mitosis in the tumors. (a) The mitotic index was higher in tumors of L12 rats compared to the other groups (***P <0.001). (b) The apoptotic index was augmented in tumors of L3 v. L12 (*P <0.05). (c) The mitotic/apoptotic ratio was significantly higher in L12 when compared to L3 (***P <0.001). Values are means ± s.e.m. of each group. Comparisons were performed by ANOVA I and Bonferroni’s test as post hoc. L3, litter of three pups per mother; L8, litter of eight pups per mother; L12, litter of 12 pups per mother.

Fig. 6 High milk intake reduces expression of PCNA. (a) Representative microphotographs (400×) of tumors immunostained to reveal PCNA. (b) PCNA-inmunostaining score. The expression of PCNA determined by IHC was higher in L12 compared whit L8 (*P <0.05). Values represent mean ± s.e.m. of 8–10 fields of each preparation from 6 to 19 animals/group. Comparisons were performed by Kruskal–Wallis’ test and Dunn’s test. L3, litter of three pups per mother; L8, litter of eight pups per mother; L12, litter of 12 pups per mother.

Fig. 7 High milk intake tends to reduce expression of Ki67. (a) Representative microphotographs (400×) of tumors immunostained to reveal Ki67. (b) Ki67-immunostaining score. There is a tendency to increase the expression of Ki67 in the litter of 12 (L12) although it is statistically not significant (P = 0.088). Values represent mean ± s.e.m. of 8–10 fields of each preparation from 6 to 19 animals/group. Comparisons were performed by Kruskal–Wallis’ test and Dunn’s test. L3, litter of three pups per mother; L8, litter of eight pups per mother; L12, litter of 12 pups per mother.

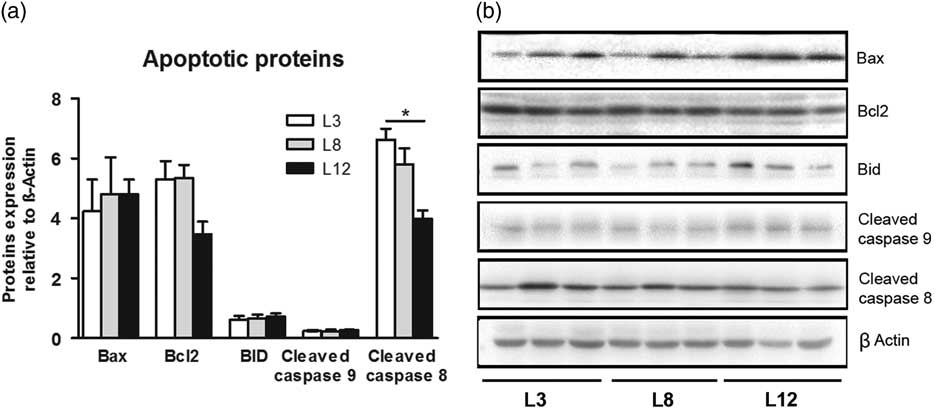

To further investigate the involvement of the apoptotic pathways in the effects of lactation on tumor biology, we determined the expression of caspase 8, Bid, Bax, Bcl2 and caspase 9 by Western blot in tumors from L3, L8 and L12 groups. The expression of the mitochondria-mediated apoptosis proteins like Bax, Bcl2, Bid and caspase 9 were similar in the tumors of the three groups. However, cleaved caspase 8, a death receptor-mediated apoptosis protein, was higher in L3 tumors than in L12 tumors (P <0.01; Fig. 8). All these results indicate that higher intake of maternal milk, early in life, is associated with the activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway in mammary tumors.

Fig. 8 High milk intake activates the extrinsic apoptotic pathway. (a) No significant differences were found in the expression of Bax, Bcl2, Bid and caspase 9 between the three groups. Cleaved caspase 8 levels were higher in L3 than L12 tumors (*P <0.05). (b) Representative Western blots for each studied protein. Values are means ± s.e.m. for groups of six tumors. Comparisons were performed by ANOVA I and Bonferroni’s test as post hoc. L3, litter of three pups per mother; L8, litter of eight pups per mother; L12, litter of 12 pups per mother.

Discussion

In our current study, we demonstrated the protective role of a high consumption of maternal milk during lactation in mammary carcinogenesis later in life, which is related to variations in tumor proliferation and apoptosis.

The dissimilarities in body weight observed in the different groups of animals were exclusively caused by the variations in milk intake. There is evidence that weight gain accelerates mammary carcinogenesis in rats.Reference Matthews, Zhu and Jiang30 However, our litters of three pups per mother had higher body weight and simultaneously a lower incidence of tumors. These results suggest that the increase of maternal milk consumption during postnatal life generates greater exposure of the animal to epigenetic and/or nutritional compounds that participate in the prevention of cancer development, thus preventing the occurrence of the disease in adult life.Reference Melnik and Schmitz9, Reference Melnik, John and Schmitz31 In agreement with our results, in the human, body size in early life has been consistently associated with reduced breast cancer risk.Reference Shawon, Eriksson and Li32 However, the mechanisms of this association have not been clarified.

In our animal model, the consumption of maternal milk does not produce a significant increase of the intra-abdominal fat, although a tendency can be observed in those animals showing higher weight. In a recent analysis that relates human body fat deposits to the risk of developing cancer, there was no association between bigger deposits of visceral adipose tissue and an increase in the development of cancer.Reference Gupta, Pandey and Ayers33 However, other studies conclude that central obesity can be a key risk factor for the development of breast cancer.Reference Schapira, Clark and Wolff34, Reference Nagrani, Mhatre and Rajaraman35 In our animal model, the increasing trend observed in abdominal fat content in animals that maintained a higher consumption of breast milk (L3) was associated to an even lower mammary carcinogenesis.

Moreover, both the volume and the composition of milk produced by mothers with litters of different sizes were disparate. The average volume of milk sucked by each pup in L3 was more abundant and with higher protein content than in the other groups. On the contrary, the L12 pups had a smaller volume of milk per animal, and lower total protein and higher lactose content. Although the volume of milk obtained by each pup is lower in L12, the number of pups to be nursed was higher, which indicates a higher production of milk of lower nutritional quality. That compensates the similar caloric values of the milks obtained in the three groups. These observed variations in milk composition suggest a compensation mechanism in L12 to achieve an adequate caloric value, at the expense of the increase in lactose content. These results in animals agreed with those obtained in previous investigations in humans.Reference Nommsen, Lovelady, Heinig, Lönnerdal and Dewey36

The association of different factors present from early life and the development of diseases of the adult life has received an increasing interest. It has been observed that perinatal factors are involved in the development of breast cancer in offspring.Reference Ekbom, Hsieh, Lipworth, Adami and Trichopoulos37–Reference Sanderson, Williams and Daling39 Our present results showing lower incidence and longer tumor latency in the animals that maintained a higher intake of maternal milk support that an appropriate consumption of maternal milk protects against mammary carcinogenesis. Moreover, a noticeable tendency to a longer survival was observed in those animals with higher intake. Interestingly, we also observed that as maternal milk consumption decreased, the rate of tumor growth in the adulthood tended to increase.

The mechanisms by which breastfeeding could modify carcinogenesis development in adult life are still unknown. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study carried out in animals in order to generate a controlled environment, avoiding the intrusion of food, hormonal factors, stress situations and physical activity that could come to intervene in tumor development. Additionally, the molecular study of tumors provided relevant information for a better understanding of the association between lactation and mammary carcinogenesis.

Carcinogenesis is directly related to the misbalance between proliferation and apoptosis. Routine techniques used to measure cell proliferation include mitosis count and immunohistochemistry-chemical detection of cell cycle proteins (PCNA, Ki-67).Reference Elias40 In the present study, we showed a greater cell proliferation of tumors in rats with a lower consumption of breast milk (L12) evaluated by immunostaining of PCNA and counting of mitotic figures in histological sections. These results are in accordance with the augmented tumor incidence and the tendency of tumors to grow faster in this group of animals.

The inactivation of programmed cell death, or apoptosis, is crucial for cancer development.Reference Budihardjo, Oliver, Lutter, Luo and Wang41 Our results show an increase in the expression of cleaved caspase 8 in the tumors of the animals that received a greater consumption of milk (L3), demonstrating the activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway. This activation coincides with the higher number of apoptotic bodies found in the tumor sections. These findings suggest that there are extrinsic factors associated to lactation in early life that would limit tumor development in adulthood.

Tumor progression also depends on the dialogue between tumor epithelial cells and the surrounding stroma cells.Reference Mueller and Fusenig42 Among the different types of cells that surround the tumor, the most abundant are those that make up the adipose mammary tissue.Reference Fletcher, Sacca and Pistone-Creydt43 On the other hand, variations in the differentiation of the mammary gland could explain a modified susceptibility to cancer development. Breast milk contains micro-RNAs responsible for modulating the expression of the infant’s genes.Reference Melnik and Schmitz9 These micro-RNAs are internalized in extracellular vesicles called exosomes and reach the systemic circulation of the newbornReference Melnik and Schmitz9, Reference Bakhshandeh, Kamaleddin and Aalishah44 where they exert their epigenetic regulation. Therefore, breastfeeding can generate an epigenetic imprinting in the infant that modulates the risk of developing diseases in adult life. In order to obtain a more complete understanding on the subject, genetic and epigenetic studies on the mammary tissue of animals with different consumption of maternal milk are being carried out in our laboratory.

In summary, we established an in vivo model of differential milk consumption to study the specific role of lactation in the risk of developing mammary carcinoma. We demonstrated that animals maintaining more access to maternal milk during postnatal life generate a lower incidence of mammary cancer in the adulthood. We also found a reduction in the proliferation and an increase in apoptosis in the tumors of those animals that maintained a higher intake of milk during the postnatal period. Taken together, our research underscores the importance of lactation in mammary cancer etiology and progression and lays the groundwork for future studies to explore the specific role of maternal milk.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply indebted to Dr Belen Hapon, Vet. Paula Ginevro and Mr Juan Rosales for their excellent technical assistance and to Laboratories Innovis for the determinations of milk components.

Financial Support

This work was supported by Instituto Nacional del Cáncer, identified as number B11 according to resolution of the Ministry of Health of Argentina number 493/14.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guides on the care and use of laboratory animals (National Institutes of Health) and have been approved by the institutional committee (CICUAL) of the School of Medicine of the National University of Cuyo, Mendoza, Argentina.