1. Introduction

An important body of literature has focused on the question of why Jews throughout history have tended to be more literate and educated than non-Jews. One prominent explanation is that the drive to education was related to the restrictions prohibiting Jews to own land. For example, Kuznets and Finkelstein (Reference Kuznets, Finkelstein and Louis Finkelstein1960) points out that these restrictions—together with fear of expulsion from areas where they lived, justified by the experiences of such expulsions in the past—led Jews to focus on occupations and skills that were portable, and to invest in their human capital more than in production capital.Footnote 2 As a result, they were more present in trade, finance, and medicine. In order to perform such occupations, Jews needed to achieve above-average education. Another prominent explanation, suggested by Botticini and Eckstein (Reference Botticini and Eckstein2005, Reference Botticini and Eckstein2007, Reference Botticini and Eckstein2013), is that Jews in the pre-modern period were more literate than the general population because every Jewish male was expected to read from the Torah, and to teach his son to read the Torah.Footnote 3

Focusing on interwar Poland, we find that Jews were on average more literate and educated than non-Jews. However, this pattern is driven by a composition effect. In particular, most Jews lived in cities and most non-Jews lived in rural areas, and people in cities were more educated than people in villages regardless of their religion. For example, in 1931, 24% of non-Jews were illiterate, compared to 15.4% among Jews. Jews living in cities were less literate than the general city population, while Jews living in rural areas were more literate than the general rural population. Future research on Jewish education levels should take into account this composition effect, and explore why urban Jews were relatively less educated in Poland. This might involve refining existing theories to lay out the conditions under which Jews were more educated and how educational choices affected and were affected by the constraints on and decisions by Jews of where to live.

2. Data from the 1921 and 1931 censuses

We use data collected in two censuses in interwar Poland, in 1921 and 1931.Footnote 4 The published information includes only aggregated data; unfortunately, the census lists with the individual information did not survive World War II. We also use the updates to the censuses published in the annals of the Main Statistics Office (Rocznik statystyczny) for the 1920s and abbreviated annals (Maly rocznik statystyczny) for the 1930s. The censuses included the whole population, and the data are fairly representative of the population, although the 1921 census has a number of important shortcomings [Statystyka Polski (1938), Dłuska and Holzer (Reference Dłuska and Holzer1958)].Footnote 5 The questions in the censuses were open ended. What is important for our purposes is that the Polish population census allows us to identify Jews . “Religion,” according to the instructions, was the self-declared religious institution to which the person formally belonged. The 1921 census asked about nationality and religion, while the 1931 census asked about mother language and religion. The data on literacy were collected based on self-declared answer to the questions “can you read?” and “can you write?” The illiteracy and education data were reported in aggregate and by religious groups.

Previous literature has raised the issue of whether Jewish illiteracy may be overstated if Yiddish or Hebrew were not recognized as legitimate languages. Corrsin (Reference Corrsin1999) raised this issue in the context of the Russian census of 1897,Footnote 6 and Corrsin (Reference Corrsin1998) in the context of the Polish census of 1921. This issue was widely recognized and discussed by Polish statisticians in the early 20th century, and they actively aimed at countering it in Polish censuses.Footnote 7 After doubts whether they succeeded in 1921, the census question in 1931 explicitly asked “can read in any language?” and “can write in any language?” Indeed, according to Corrsin (Reference Corrsin1998), the 1931 census does not misrepresent literacy among Jews. For these reasons, while the cross-sectional comparisons seem meaningful, comparisons across censuses are more problematic [Stampfer (Reference Stampfer and Shmuel1987)]. Accordingly, we make comparisons between the education and literacy of Jews and non-Jews within each census, but we avoid comparisons across the two censuses.

3. Findings

3.1 Most Poles lived in rural areas and most Jews lived in urban areas

Figure 1 shows that most Poles lived in rural areas and most Jews lived in urban areas. Specifically, in 1921, 74% of the Jewish minority lived in urban areas. They accounted for 32.4% of the urban population, even though they only constituted 10.8% of the total population in Poland.Footnote 8 ,Footnote 9 In rural areas, where the overwhelming majority of the total population (74%) resided, Jews constituted only $3.7{\rm \%}$![]() . In 1931, Jews constituted $9.8{\rm \%}$

. In 1931, Jews constituted $9.8{\rm \%}$![]() of the total population.Footnote 10 They accounted for $27.3{\rm \%}$

of the total population.Footnote 10 They accounted for $27.3{\rm \%}$![]() of the total urban population, and only for $3.2{\rm \%}$

of the total urban population, and only for $3.2{\rm \%}$![]() of the rural population. In both censuses, age distributions are quite similar across urban and rural, Jewish and non-Jewish populations (Figures A1(a)–(c) and A2(a)–(c)).

of the rural population. In both censuses, age distributions are quite similar across urban and rural, Jewish and non-Jewish populations (Figures A1(a)–(c) and A2(a)–(c)).

Figure 1. The Polish population mostly lived in rural areas, while Jews mostly lived in urban areas.

Note: The figure presents the Polish population. The data sources are the censuses of 1921 and 1931.

Moreover, and consistent with Botticini and Eckstein (Reference Botticini and Eckstein2013), we find that the proportion of Jews working in agriculture is much smaller than in the general population. In 1921, 74% of the Polish population worked in agriculture, but less than 10% of Jews did. Similarly, in 1931, 61% of the Polish population worked in agriculture, but only 4.02% of Jews. Outside of agriculture, Jews were mainly concentrated in the sectors of mining, industry, commerce, and insurance.

3.2 Jews were more literate than the general population overall, but less literate in urban areas

In the 1921 census, we consider as “illiterate” people 10 years or older who declared “could not read.” The 1931 census did not include a comparable category, so we consider as illiterate people 10 years or older who declared “could neither read nor write.”Footnote 11 On average, we find that Jews were more literate than non-Jews.Footnote 12 In 1921, while 33.2% of non-Jews were illiterate, only 28.86% of Jews fell into this category. The difference was even starker in 1931—24% of non-Jews were illiterate compared to 15.4% among Jews. However, Figure 2 reveals that in cities Jews were less literate than the general population, while in rural areas Jews had similar (in 1921) or lower (in 1931) illiteracy rates.Footnote 13, Footnote 14

Figure 2. In aggregate, Jews had a lower illiteracy rate than non-Jews. In urban areas Jews had a relatively higher illiteracy rate, and in rural areas a relatively lower illiteracy rate.

Note: The figure presents the illiteracy rates of Jews and non-Jews for people aged 10 and older. The data sources are the censuses of 1921 and 1931.

Since during both censuses about 3/4 of Jews resided in urban areas and 3/4 of the total population lived in rural areas (see Figure 1), a general comparison without distinction into urban and rural areas compares mostly urban Jews to mostly rural non-Jews. The population in urban areas was significantly more literate than that in rural areas, for both the Jewish minority and the overall population. Urban Jews—even though less literate than the overall urban population—were still more literate than the rural non-Jewish population. Thus, in the aggregate statistics, Jews were more literate than non-Jews.

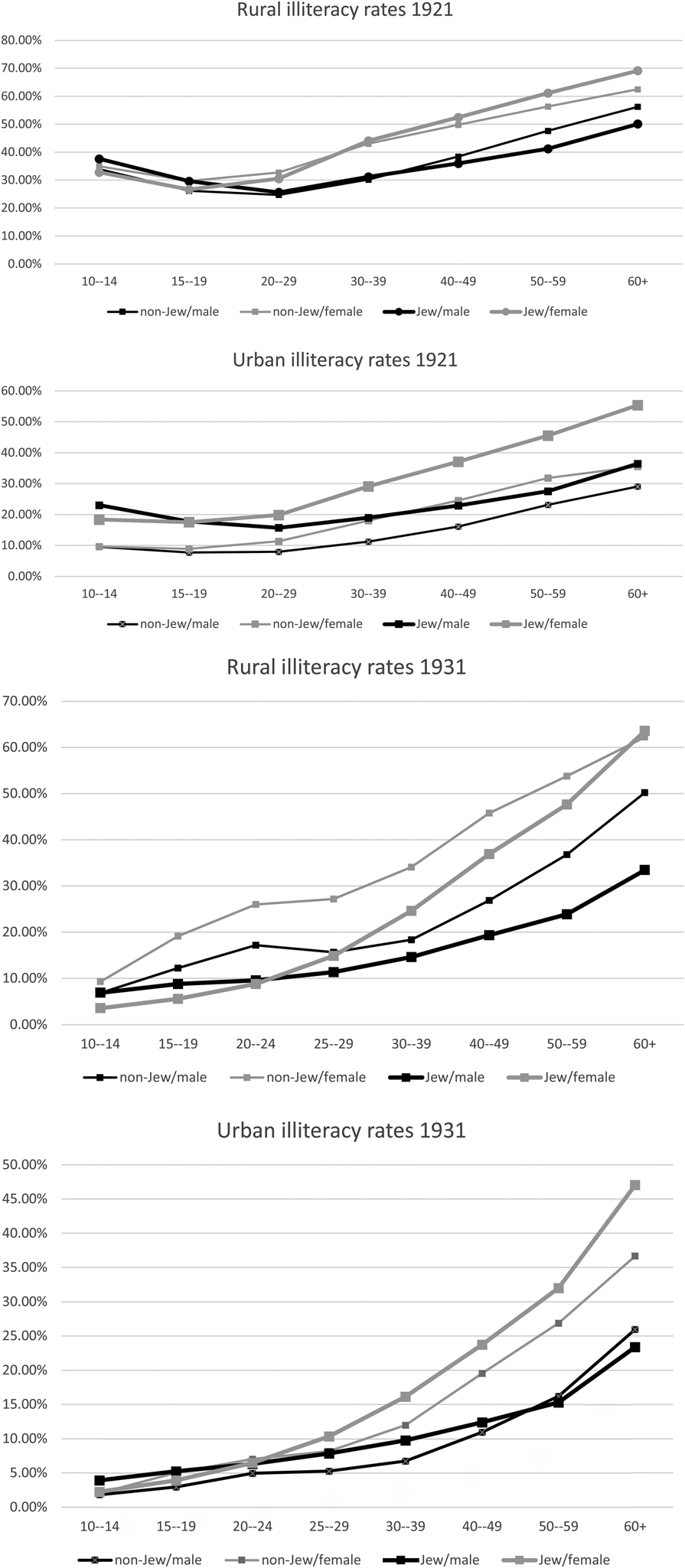

Panels (a)–(d) of Figure 3 show that these patterns are overall similar when considering different age groups, and for both men and women.Footnote 15 Interestingly, however, in rural areas in 1921, Jewish men aged 40+ were less illiterate than their peers in the general population, while younger Jewish men were more illiterate. In contrast, Jewish women aged 30+ were more illiterate, while younger Jewish women were less illiterate than younger women in the general population.Footnote 16

Figure 3. Jewish and non-Jewish literacy in 1921 and 1931, by rural and urban localities.

Note: The figures present the illiteracy rates of Jews and non-Jews for people aged 10 and older. The data sources are the censuses of 1921 and 1931.

3.3 Jews were more often home-schooled than the general population

The 1921 census reported the highest obtained level of education: primary, home-schooling, secondary, occupational, and post-secondary education.Footnote 17 Attending primary- or home-schooling was compulsory in all areas that were included in Poland in 1921.Footnote 18 The remaining categories—occupational, secondary, and post-secondary education—were post-primary education levels.Footnote 19

We find that Jews differed significantly from the general population in their compulsory education. Primary education includes state-provided primary-schooling system. The length of the education in state primary schools differed depending on time and geography, and could be between 4 and 7 grades. This is because people in the considered age group were mostly educated before World War I, and thus educated in the systems of Prussia, Russia, or the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Those differences are not marked in the census. All primary schools are considered in the same category. A significant fraction of the population obtained all its education at home, which is reported in the census as home-schooling. It is difficult to determine the level of home-schooling, but it was likely considered equivalent to primary schools in the level of instruction. Jews would often prefer home-schooling over state schools, because state-schools typically required attendance on Saturdays. Moreover, Jewish heders (traditional Jewish community schools) were counted as home-schooling, since they were not part of the state-provided primary-schooling system. Indeed, we see in the census that more Jews in the analyzed age group were home-schooled (22.7%) than the overall population (13.1%). State-provided primary schools were attended more often by the overall population (30.1%) than by Jews (22.7%). When analyzed separately for rural and urban areas, the participation rates in state-provided primary schools or home-schooling are very similar (see Figure 4). There was not much control or oversight of home-schooling in Poland during the early 20th century, which may have resulted in higher illiteracy rates. Moreover, the numbers in Figure 4 indicate that around 50% of population did not receive full primary education or equivalent home-schooling. This may have been due to the war years, and because the obligation for education was poorly executed [Landau and Tomaszewski (Reference Landau and Tomaszewski1971)].

Figure 4. Jews were more often home-schooled while the general population more often attended state-provided primary schools.

Note: The figure presents compulsory levels of education (home-schooling and state-provided primary education) of people aged 30 and older. The source is the Polish 1921 population census.

3.4 Jews attained higher levels of education than the general population overall, but lower levels in urban areas

The 1921 census reports three categories of post-primary education: occupational, secondary, and post-secondary education. Nationwide, 4.2% of Poles aged 30 and older achieved some level of post-primary education, as compared with 5.9% of Jews. Figure 5 suggests that this education advantage is again a result of a composition effect: Jews, unlike non-Jews, predominantly lived in urban areas, and the urban population was generally more educated than the rural population regardless of their religion. In urban areas, Jews were in fact less likely to acquire post-primary education. In rural areas, Jews and non-Jews were almost equally likely to acquire post-primary education. Table 1 shows that these results hold for each of the post-primary education categories—secondary, occupational, and post-secondary education.

Figure 5. Jews were more likely to obtain post-primary education than the general population on average, but in urban areas (and to some extent rural areas) they were less likely to do so.

Note: The figure presents the post-primary education of people aged 30 and older. The data source is the Polish 1921 population census.

Table 1. Post-primary education of Jews and non-Jews, age group 30+, 1921

Note: The table presents the post-primary education of people aged 30 or more. The data source is the 1921 Polish population census. The first three columns present the percentage of people with post-primary education. The next nine columns break down this percentage to the type of post-primary education: occupational (columns 4–6), secondary (columns 7–9), or post-secondary (columns 10–12) education. These post-primary education types are defined in section 3.3.

The numbers reported in Figure 5 and Table 1 refer to people who are 30 or older, as they presumably already completed their education. Table A1 shows that these results hold for other age groups, and also for men and women separately: in urban areas Jews were less likely to achieve post-primary education. The one exception is women aged 20–29 in the category “post-secondary education.” In this age group, Jewish women appear more likely to obtain a university diploma than non-Jewish women.

In rural areas, the levels of post-primary education were in general low, and the differences between Jewish and non-Jewish population were very small and varied across the age–gender–category group. However, a general pattern is visible: Jews appear a bit more likely than non-Jews to obtain a given level of post-primary education in older age groups, while they are less likely to do so in younger age groups.

4. Discussion

We conclude that the literacy and education advantage of Jews in interwar Poland masks a composition effect. Jews tended to live in urban areas, and urban people tended to be more educated than rural people regardless of their religion. When comparing Jews to non-Jews in urban places, there is no longer any Jewish education advantage, and Jews in fact appeared less educated than the urban non-Jewish population.

This paper does not explain why there was a Jewish literacy advantage in rural areas and literacy disadvantage in urban areas. The higher tendency of Jews to live in urban areas might in itself reflect a greater desire to acquire education, or it might reflect a constraint that prevented more Jews from living in rural areas. Indeed, unlike the general Polish population at the time, and consistent with Botticini and Eckstein (Reference Botticini and Eckstein2013), most Jews worked outside of agriculture and in more urban occupations such as commerce and insurance. The patterns we document may also reflect the tendency of Jews to hold similar education regardless of whether they lived in the city or in a rural area [Spitzer (Reference Spitzer2019)].

Moreover, while our paper illuminates patterns of education for Jews in Poland, the results do not apply universally. Polish Jews were less literate than Jews elsewhere, especially in New Russia. In Belarus and the Ukraine, Jews were much more literate and non-Jews were much less literate [Spitzer (Reference Spitzer2019)]. In the context of 1871 Prussia, Jews seemed to have had no significant literacy advantage with respect to Catholics in towns but an advantage in villages and manors [Becker and Cinnirella (Reference Becker and Cinnirella2020)]. Like in all empirical settings, estimates of Jewish advantage may vary depending on the historical and institutional setting [see also Stampfer (Reference Stampfer and Shmuel1987)]. A natural next step for theories of the Jews is to better understand the conditions under which Jews had an educational advantage, and the relationship between education and location composition effects.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jared Rubin, Joel Mokyr, Yannay Spitzer, Santiago Perez, Lukasz Pomorski, Nicky Irvine Halterman, Scott Kamino, and David Yang for helpful comments and discussions. We also thank Piotr Kuszewski for invaluable help with data collection.

Appendix

See Figures A1 and A2 and Table A1.

Figure A1. (a)–(c) The age distribution of Jewish and non-Jewish populations, 1921.

Figure A2. (a)–(c) The age distribution of Jewish and non-Jewish populations, 1931.

Table A1. Post-primary education of Jews and non-Jews, various age groups, 1921