1 Introduction

Female genital cutting (FGC) is a nearly ubiquitous cultural practice among ever-married women in Egypt, Eritrea, Mali, and Sudan, and is practiced elsewhere in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.Footnote 1 According to the World Health Organization, around 140 million women and girls have been subjected to FGC, and 30 million more girls will be cut in the next decade if current trends continue. While some defend female circumcision as a long-standing, widely-practiced societal tradition, human rights activists view FGC as one of the most common forms of institutionalized violence committed against girls in the developing world. Ironically, the practice is overwhelmingly undertaken at the behest of mothers who believe that their actions are morally, socially, and economically justified despite the fact that their own experiences with FGC, and its aftermath, are often described as traumatic.Footnote 2

This paper explores population-level patterns in FGC as well as women's attitudes toward the perpetuation of female circumcision in Egypt. While existing studies tend to focus on individual-level factors—like a woman's education level or socioeconomic status—we focus on meso-level factors associated with a woman's religious community and her family structure. Using data from multiple waves of the Demographic and Health Surveys, we find that Christian women have seen sharper declines in FGC than their Muslim counterparts despite comparable average levels of education. We argue that Christian religious leaders played a key role in encouraging community members to converge on a change in social practice with regard to FGC. For Egyptian Muslims, on the other hand, conflicting religious edicts put forward by state-sponsored elites and the leadership of Islamist organizations, like the Muslim Brotherhood, have sowed uncertainty regarding the desirability of FGC as a practice. Our arguments emphasize the importance of social coordination within religious communities as key to ending FGC.

In order to explore the mechanisms underlying evolving attitudes toward FGC, we conduct an original survey of young mothers in Greater Cairo. We find that Muslim and Christian women have divergent beliefs about how religious leaders in their communities view FGC. We find that Christian women believe that their religious leaders seek an end to FGC, an empirical result consistent with our conclusion that religious elites have a key role to play in influencing social change on this issue.

While differences in FGC rates across these two religious communities are substantively significant, they belie forms of within-community variation. In particular, we also find that socialization within families shapes mothers' attitudes regarding FGC. For older women, the gender of a first-born child—an exogenous variable in Egypt where pre-natal sex selection is rare—impacts attitudes toward FGC. In particular, older Muslim and Christian women with first-born sons are more likely to believe FGC should continue even though Christian women have lower levels of support for the continuation of FGC, overall. We hypothesize that having sons invests mothers, to some degree, in traditional values that can impact attitudes toward gender-related practices and social norms. The first-born gender effect is attenuated for younger mothers, however, and among younger Muslim women, a male first-born child is associated with the opposite result. We believe that the Islamic Revival, which began in the 1970s, may be leading younger Muslim mothers to eschew more traditional patriarchal values as they adopt forms of Islamic modernism that require women to serve as virtuous exemplars of religious morality, regardless of circumcision status.

More broadly, our findings contribute to understanding the conditions under which harmful social practices, particularly ones that hurt women and girls, perpetuate or end [e.g., Mackie (Reference Mackie1996), Bicchieri (Reference Bicchieri2016)]. The mechanisms that we describe draw attention to the importance of religious authority in encouraging or blocking changes in social norms. These issues are particularly salient in the study of the Middle East where religious elites are believed to be influential in the shaping of societal attitudes and behaviors [e.g., Eickelman and Piscatori (Reference Eickelman and Piscatori1996), Rubin (Reference Rubin2017), Yildirm (Reference Yildirm2019)]. There exists systematic variation in support for harmful social practices even within religious communities, however. Our findings regarding the impact of the first-child gender on attitudes toward FGC contribute to a growing literature on the effect of child gender on attitudes toward women by extending application of this particular strategy for causal inference beyond North America [Warner (Reference Warner1991), Downey et al. (Reference Downey, Braboy Jackson and Powell1994), Warner and Steel (Reference Warner and Steel1999), Washington (Reference Washington2008), Shafer and Malhotra (Reference Shafer and Malhotra2011), Glynn and Sen (Reference Glynn and Sen2015)].

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes anthropological accounts of the practice of FGC in Egypt, our case study, as well as a summary of the primary empirical findings in the existing literature. Because most of these findings are focused on the individual-level attributes of mothers, we describe our motivation for studying meso-level factors, like family and religious group socialization. Section 3 describes temporal variation in the prevalence of FGC by the religious group, provides a qualitative discussion regarding how both Christian and Muslim religious leaders have engaged with the issue of FGC, and offers original survey data from Greater Cairo regarding how women view the attitudes of their religious elites. Section 4 adds family socialization—as proxied by the first-child gender—to the set of factors which influence attitudes toward FGC for both Christians and Muslims. The final section concludes and elaborates on the broader implications of our findings.

2 Female genital cutting in Egypt

In this paper, we focus on the abandonment of FGC, a harmful practice that exists in nearly forty countries around the world, the majority of which are in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. FGC is often considered a cultural or religious practice, although no religious text is known to require the cutting of female genitalia. The practice of FGC, particularly in its extreme forms, can have harmful and permanent effects on the physical, social, and emotional health of women and girls. Potential health consequences of FGC include infection, shock, hemorrhage, scarring, infertility, and difficulties with menstruation, pregnancy, and childbirth.

We focus on Egypt for two reasons. Although FGC was nearly universal for both Muslim and Christian women age 40 and older, rates have declined over the last 20 years. As a result, Egypt provides an important locale for understanding how and when harmful social practices witness change. At the same time, rates of FGC decline have been uneven. Its religious diversity and changing rates of FGC prevalence make Egypt an ideal setting for examining how various societal factors—like religious community and family structure—impact attitudes toward FGC and variation in rates of decline across different religious populations. Further, Egyptian women represent about one-fourth of women worldwide subjected to FGC, though the form of cutting that takes place in Egypt is less severe than in other African countries.Footnote 3

Christians are believed to make up between 5 and 10 percent of Egypt's total population, while the remainder of Egyptians are Muslim. While there exists considerable discussion within the Muslim community in Egypt about the desirability and permissibility of the practice, a different trend seems to be underway within the Christian community in Egypt. In a sample of ever-married women in Minya governorate, Christian women are having fewer daughters circumcised, less extensive forms of cutting are used, and the practice is seen as less beneficial than among their Muslim neighbors [Yount (Reference Yount2004)]. In a sample of 1,200 women in urban Giza governorate surveyed in 2009, Christians reported 34 percent of their daughters have been subjected to the practice while the percent for Muslims was about 55 percent [Blaydes and Gillum (Reference Blaydes and Gillum2013)]. This paper explores this divergence between religious communities while also examining variation in attitude toward FGC within religious communities.

2.1 Anthropological Accounts

There are a variety of justifications offered by women regarding why FGC persists. Common reasons given include religious tradition or requirement, cleanliness, aesthetics, ensuring abstinence until marriage, preventing adultery, and improving a woman or girl's prospects in the marriage market. Where it is prevalent, FGC is frequently associated with Islam, despite the fact that FGC is not practiced in most of the Islamic world. Moreover, the practice of FGC in the Nile Valley began before the arrival of Islam.

Anthropologists focusing on women's issues in Egypt have written extensively about the prevalence of FGC. Seen as a rite of passage for girls moving from childhood to womanhood, FGC is reported by Egyptian women as being a practice that contributes to cleanliness, which is required by religion, increases their marriage prospects and prevents adultery, among other things [El-Kholy (Reference El-Kholy2002, p. 92)]. While religious commitment and associated norms of personal morality occupy an important place in the discourse around FGC, religion is often conflated with other objectives to create ambiguity about the incentives facing women and families making choices about FGC. Bibars, conducting fieldwork among low-income women in the 1990s, finds FGC was done to “beautify girls, to please their husbands, or to restrain sexual desire” (2001, p. 150). According to Bibars,

“…all the women and young girls I met from the age of 16 to 50 were circumcised, and all young mothers were intending to circumcise their young daughters. Education, age, class and profession did not change the picture. All were advocates of female circumcision. When they were asked about the reason, religion was cited as the first excuse” [Bibars (Reference Bibars2001, p. 150)].

Among her informants, women were responsible for transmitting social messages about the practice while simultaneously suffering from their own traumatic memories of “screaming, pain, forcing legs apart, scissors and knife” [Bibars (Reference Bibars2001, p. 150)]. El-Kholy (Reference El-Kholy2002, p. 88)—conducting fieldwork in low-income areas of Cairo in the 1990s—describes the “universality of the practice among women in my sample, both Muslims and Copts: 100 percent were circumcised, and 100 percent had either already circumcised their daughters or were planning to circumcise their younger ones when they were a little older.” According to one informant, the biggest “ayb, or shame, for a woman is to be uncircumcised [El-Kholy (Reference El-Kholy2002, p. 91)].” Common across all accounts is the idea that the practice and perpetuation of FGC rests largely in the hands of mothers making what they believe to be a decision in the family's best interests.

2.2 Empirical approaches

Existing empirical studies examining attitudes toward FGC in Egypt have typically focused on the socio-economic status and educational background of mothers, who are seen as key decision-makers associated with daughters' FGC outcomes. Individual-level factors have been widely discussed in the existing literature and are important predictors of support for FGC. Yount (Reference Yount2002) finds—in a study of FGC in Upper Egypt—that a mother's educational level is negatively associated with both her own circumcision status as well as her intent to circumcise her daughter. Suzuki and Meekers (Reference Suzuki and Meekers2008) find that Egyptian women exposed to two or more FGC-related media messages are 1.6 times more likely than unexposed women to support discontinuing FGC. Modrek and Liu (Reference Modrek and Liu2013) find that maternal education is associated with declines in FGC while paternal education is a less robust indicator of FGC status. In addition, high levels of exposure to FGC-related media messaging may also be associated with reduced support for FGC [Modrek and Liu (Reference Modrek and Liu2013)].

We focus our attention on two meso-level factors associated with the practice of FGC.Footnote 4 In particular, we explore the socialization and attitude formation of women within their families. While a number of influential studies have considered household-level variables, we focus on one particular aspect of the family—the gender of the first-born child. Why examine first-born child gender? Sociologists have shown that the gender of one's children impacts a variety of attitudes. Samples of the US and North American populations have been shown to be influenced by child gender [Warner (Reference Warner1991), Downey et al. (Reference Downey, Braboy Jackson and Powell1994), Warner and Steel (Reference Warner and Steel1999), Shafer and Malhotra (Reference Shafer and Malhotra2011)]. For example, Shafer and Malhotra (Reference Shafer and Malhotra2011) find that having a daughter vs a son leads men to reduce support for traditional gender roles. US elites have also been shown to be influenced by child gender. Washington (Reference Washington2008) finds that conditional on the total number of children, having daughters increases a US Congressperson's propensity to vote liberally on issues related to reproductive rights. Glynn and Sen (Reference Glynn and Sen2015) find that judges with daughters “consistently vote in a more pro-woman fashion on gender issues than judges who have only sons.”

A variety of theoretical mechanisms have been proposed to explain the relationship between child gender and parental attitudes and behavior. These include greater exposure to issues regarding gender equality when having a daughter [Warner and Steele (Reference Warner and Steel1999)]; children's engagement in non-gender-conforming tasks [Brody and Steeleman (Reference Brody and Steelman1985)]; a preference that mothers of boys stay home rather than outsource child care [Downey et al. (Reference Downey, Braboy Jackson and Powell1994)]; greater paternal investment in children when there is at least one male child [Harris and Morgan (Reference Harris and Philip Morgan1991)]; and that mothers of boys believe marital separation is less likely [Katzev et al. (Reference Katzev, Warner and Acock1994)].Footnote 5 While most studies on child gender focus on elite and US samples, we focus on Egypt, where we also expect that child gender may affect parental attitudes. Because we cannot know for sure that women in Egypt are not using a “stopping” rule, we restrict our analysis here to a woman's exogenously-determined first-born child.Footnote 6 Sex selection is rare in Egypt, where gender selection procedures are expensive given income levels. Further, we expect that sex-selection would be especially rare for a first-born child. Egyptian doctors observe that there is no point in “choosing a boy or a girl if a couple has had no children.”Footnote 7

Beyond family-level factors, we also believe that attitudes and choices regarding FGC reflect the existence of a coordination game within religious communities. In Egypt, religion is a major identity marker and marriage takes place within, not across, religious groups. Previous scholarly work suggests that harmful social practices, particularly those that seek to control sexual access to women, tend to be self-enforcing conventions maintained by individual's expectations about marriage market dynamics [Mackie (Reference Mackie1996)]. In such a scenario, practices like FGC in Africa and the Middle East, footbinding in China, and widow suicide in India can persist for decades and longer despite the harm committed against women and girls. In many cases, the social conventions force women into extreme chastity or fidelity displays [Mackie and LeJeune (Reference Mackie and LeJeune2009)].

Signals of religious commitment—like female circumcision—may also be associated with the costly demands associated with religious group membership [Iannaccone (Reference Iannaccone1992)]. In the Islamic context, Blaydes and Linzer (Reference Blaydes and Linzer2008) argue that Muslim women often face a double-bind when it comes to the perpetuation of patriarchal social norms. By signaling piety through behavior and attitudes, women enjoy better outcomes on the marriage market; demonstrations of more secular beliefs, however, advantage them in the market for high-paying employment. Although attitudes toward gender equality tend to become more favorable with economic and political modernization [Inglehart and Norris (Reference Inglehart and Norris2003)], Mackie (Reference Mackie1996) finds that harmful social conventions—like FGC—can actually increase rather than diminish with modernization.

3 Variation in FGC by religious denomination

While FGC was nearly universal for adult women born in Egypt before 1975, rates of circumcision for cohorts of younger women have declined. This has particularly been the case for Egypt's Christian community.

3.1 Temporal trends in FGC, by religion

Much of what we know about the widespread nature of FGC comes from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), conducted in over 90 countries worldwide, including many where the practice of FGC is common. These nationally-representative household surveys frequently include questions about women's circumcision status (the DHS refers to cutting as circumcision), attitudes toward female circumcision, and the circumcision status of a woman's daughters.Footnote 8 The DHS also includes the religious affiliation of the woman, for which the categories include Muslim and Christian. The vast majority of Christian Egyptians are Coptic Orthodox (approximately 90 percent) but this category also includes Coptic evangelicals and Protestant denominations (approximately 9 percent) and smaller numbers of Latin, Greek, and Maronite Catholics (less than 1 percent).

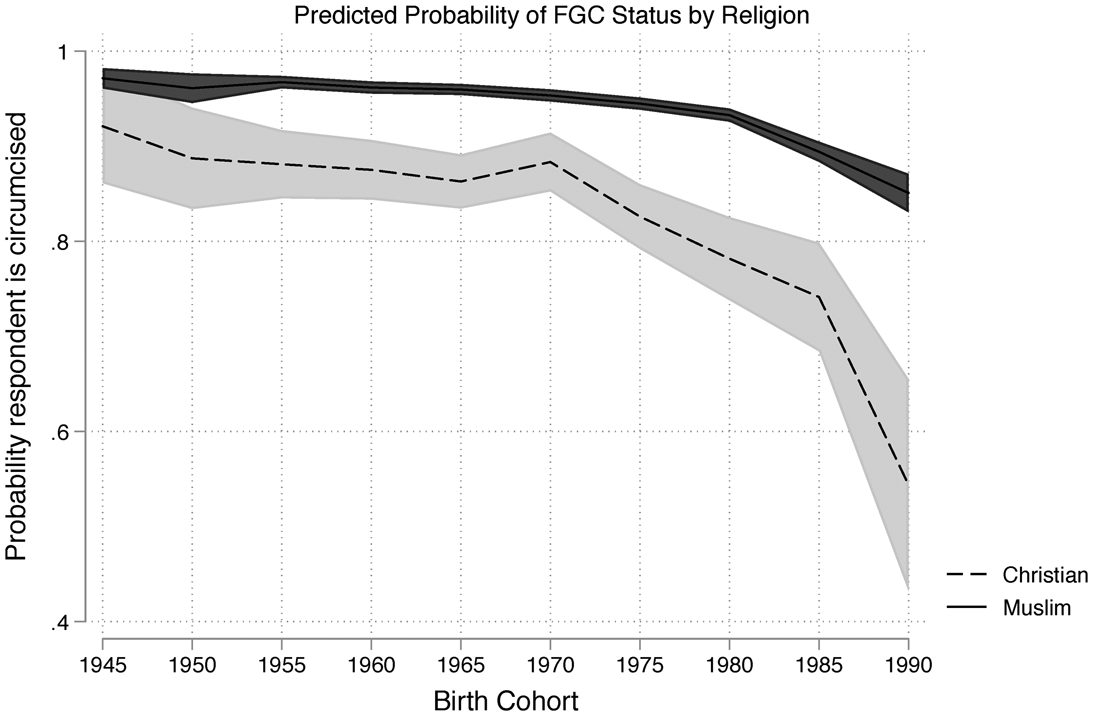

Figure 1 charts temporal change in FGC prevalence based on data from the Demographic and Health Surveys conducted in Egypt from 1995 to 2014. Specifically, we run a logistic regression where the respondent's FGC status is the dependent variable and birth cohort (in 5-year increments) is interacted with respondent religion. The figure shows the predicted probability of FGC status by religion and cohort. While Christian women have had slightly lower rates of FGC than Muslim women since the 1950s, there was a decline among Christian women starting from the cohort born in the 1970s that has continued in subsequent cohorts. While the rate is still large (more than 50 percent) in the most recent cohort for which data are available, it has nonetheless dropped substantially and at a much faster rate than it has among Muslim women.

Figure 1. Predicted values of female genital cutting for Christian (dotted line) and Muslim (solid line) women in Egypt across 5-year birth cohorts beginning in 1945. Data were drawn from DHS respondents about their own FGC status. Includes surveys from 1995, 2005, 2008, and 2014 with 71,928 respondents.

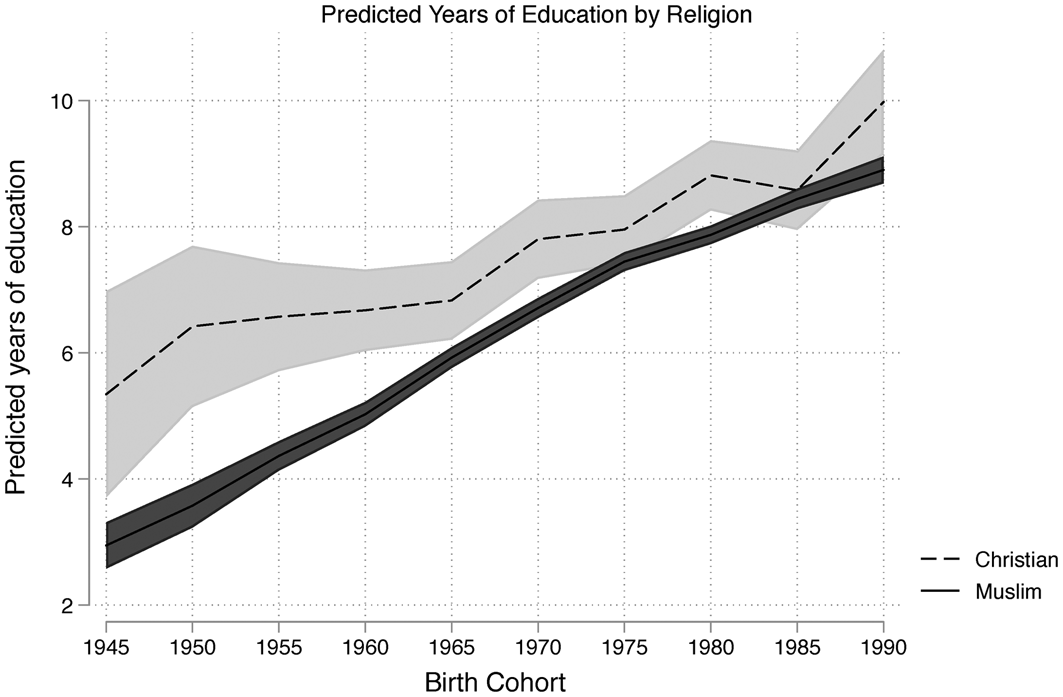

To what extent might these trends be explained by higher levels of education within the Christian community? While DHS data suggest that Christian women born in the 1940s–1960s were better educated than their Muslim counterparts, this gap began to narrow and both Christians and Muslims now have more than 8 years of education on average (see Figure 2). This suggests that even if initial differences in FGC rates across Muslim and Christian communities could be explained by differential education levels, Christians have seen much larger drops in FGC prevalence than Muslims after taking into account changes in levels of education. Further, Muslim women experience higher rates of FGC controlling for education.

Figure 2. Predicted years of education for Christian (dotted line) and Muslim (solid line) women in Egypt across 5-year birth cohorts beginning in 1945. Data were drawn from DHS respondents about their own FGC status. Includes surveys from 1995, 2005, 2008, and 2014 with 72,470 respondents.

3.2 Explaining declines among Coptic Christians

Success stories about villages that have seen major reductions in rates of FGC seem to disproportionately come from Christian areas. What explains the relatively rapid decline in FGC among Coptic women over time?Footnote 9 Beginning in the 1970s, Coptic private voluntary organizations (PVOs) like the Coptic Evangelical Organization for Social Services (CEOSS) identified FGC—along with early marriage and bridal “deflowering”—as local customs harmful to women [Yount (Reference Yount2005)].Footnote 10 In 1982, CEOSS founded a committee to raise consciousness regarding this issue and in 1995 CEOSS intensified their anti-FGC efforts with the creation of local committees in a select number of villages that brought together village leaders with a priest and local implementing team [Yount (Reference Yount2004)].Footnote 11 Private voluntary organizations sponsor workshops and educational outreach that have been reported to be highly effective in reducing the popularity of FGC as a practice.Footnote 12

Efforts to reduce the prevalence of FGC by Coptic evangelicals also extend to Coptic Orthodox communities. By 2000, the Bishopric of Public, Ecumenical, and Social Services (BLESS) of the Coptic Orthodox Church had FGC programs operating in 24 communities [Yount (Reference Yount2004)].Footnote 13 Recent scholarship has further suggested that the Coptic community has become increasingly centralized and institutionalized around an invigorated Coptic Orthodox Church, aiding the effectiveness of policy change.Footnote 14 Greater institutionalization of the Coptic Orthodox Church has combined with the existence of an organized hierarchy within the Coptic community to make it possible for church teachings to trickle down from the Coptic Pope to the bishops, priests, servants (sing: khādim), and parishioners. Coptic nuns, for example, have been seen as playing a vital role in convincing villagers not to circumcise their daughters.Footnote 15

There also exist particularly good channels of communication between Christian women and their religious and community leaders, a factor which may be consequential since women are thought to be key decisionmakers when it comes to FGC. Christian women typically go to the church frequently and are very involved with church activities [Van Doorn-Harder (Reference Van Doorn-Harder1995)]. Part of the reason for this could be related to the status of Copts as a minority group within Egypt. The Coptic Orthodox Church, perhaps out of fear of losing parishioners, encourages women—who tend to have more free time than their husbands—to go to church two to three times a week (e.g., to attend liturgy, Bible study or other church meetings). Dedicated church servants attend even more often [Jeppson (Reference Jeppson2003, p. 45)]. Christian women participate in religious services more often than many of their Muslim counterparts, who are more likely to pray at home than at a mosque.

The upper Egyptian village of Deir el-Barsha is an illustrative case of how FGC rates have been lowered in a particular locale. Deir el-Barsha is an entirely Christian village in Minya governorate with deep roots in the Coptic tradition [Hadi (Reference Hadi and Abusharaf2006, p. 111)]. Deir el-Barsha is the location of long-standing development programs organized by the CEOSS, where a women's committee helped to organize home visits to promote health education with a goal of reducing rates of FGC, particularly since the early 1990s [Hadi (Reference Hadi and Abusharaf2006, p. 114)]. Research undertaken by the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies suggest that “clergy played a crucial role in influencing the decline of practice…in Deir el-Barsha…the commitment of religious leaders not to circumcise their daughters and their public proclamation of this abstention created an atmosphere in which ordinary people felt empowered to follow suit” [Hadi (Reference Hadi and Abusharaf2006, p. 121)]. This would suggest that religious elites played a particularly important role in changing social convention.

This interpretation of norm change within Egypt's Christian community is consistent with arguments made by Finnemore and Sikkink (Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998) regarding the role played by norm leaders as the first movers in any process of communal norm change. Coptic bishops, Protestant priests, and church servants defected from the local norm, risking potential social sanction from their broader communities. But because of the important role of the Christian clergy in defining community standards for appropriate behavior, their commitment to encouraging norm change was mostly followed rather than rejected. Over time, it became increasingly clear that the community—as a whole—was moving in the direction of discouraging FGC and this sensibility allowed the Christian community to coordinate on a new equilibrium. Consistent with the mechanisms suggested by Cloward (Reference Cloward2016), Christian norm leaders were likely influenced by international normative messaging on the undesirable externalities associated with FGC.Footnote 16

3.3 Implications of the Islamic revival for persistence of FGC

The hierarchical character of the Coptic Orthodox Church contrasts with the relatively diffuse, non-stratified nature of religious organization in Sunni Islam. While Coptic Christian leaders—both Evangelical and Orthodox—have offered a relatively united anti-FGC stance since the 1990s, Sunni Islamic scholars have varied in their views on the practice of FGC [von der Osten-Sacken and Uwer (Reference Von der Osten-Sacken and Uwer2007)]. The viewpoints put forward by religious elites also exist in an environment where women and families are receiving state-sponsored messages about FGC as well as information from circumcision abatement programs sponsored by NGOs.Footnote 17

The heterogeneity of opinion within the community of Muslims on policy issues of all types is a widely accepted feature of Muslim societies. Eickelman and Piscatori (Reference Eickelman and Piscatori1996, p. 131) argue that “common to contemporary Muslim politics is a marked fragmentation of authority.” They argue that the “bearers of sacred authority” extend beyond the formal religious establishment to mystical spiritualists and lay preachers who compete with state-sponsored religious elites for social and political influence [Eickelman and Piscatori (Reference Eickelman and Piscatori1996, pp. 59 and 131)].Footnote 18 Indeed, the bureaucratization of the official religious elite in Egypt has meant that while some clerics provide support for regime policies in their capacity as civil servants, other religious scholars occupy different positions on a broad ideological spectrum [Zeghal (Reference Zeghal1999)]. In this context, it is unclear who speaks for Islam when it comes to religious interpretation and authority [Robinson (Reference Robinson2009)].

Another factor that has made it more challenging to create a unified Muslim position against FGC relates to an increase in religious practice associated with the “Islamic Revival.” Beginning in the 1970s, Egypt—and other countries in the Muslim world—witnessed a revival in Islamic practice associated with a regional resurgence in public expressions of religiosity. In many cases, this religious revival was led by lay preachers who operated separately from the traditional religious elite.Footnote 19 The Islamic Revival in Egypt has been associated with the growth of social service and charitable organizations and religious study circles [Mahmood (Reference Mahmood2005)], in addition to a marked increase in the prevalence of veiling [Patel (Reference Patel2012), Carvalho (Reference Carvalho2013)]. More generally, the Islamic Revival has involved the imposition of demanding social norms regarding issues associated with gender and gender-related practices. The increasing religiosity of society also had implications for how Egyptians formed their opinions about FGC.

Taken together, the Islamic Revival and associated fragmentation of religious authority provide the context in which Egyptians remain uncertain about the religious underpinnings of female circumcision as a practice. Indeed, one can find religious edicts on every side of the debate. For example, scholars of Egypt's Al-Azhar—a leading seat of Islamic theological learning—endorsed the practice in 1951 and 1981 [Abu-Sahlieh (Reference Abu-Sahlieh1994)]. In 1996, however, the Egyptian Minister of Health announced a ban on FGC. This decision came just 2 years after Cairo hosted the International Conference on Population and Development. During the course of the conference, CNN had broadcast the circumcision of a young girl in Cairo; FGC was widely condemned by women's health activists in the international community.Footnote 20

The ban on FGC was then challenged in Egyptian courts by a conservative Islamic scholar.Footnote 21 In 1997, an Egyptian appeals court ruled in favor of banning the procedure, arguing that it violated existing criminal codes, though the ban was not effectively enforced.Footnote 22 Following the 2007 circumcision-related death of a 12-year old girl, the Egyptian Ministry of Health issued a ban on female circumcision; formal legislation criminalizing FGC followed in 2008. Parliamentarians associated with the Muslim Brotherhood strongly objected to the criminalization of the practice during discussions in the Egyptian parliament but the legislation passed over these objections.Footnote 23 Observers have suggested, however, that top-down approaches to eliminate the practice have largely been an exercise in futility.Footnote 24 In 2012, the Muslim Brotherhood—politically ascendant in the period after the 2011 uprisings but before the 2013 popular-participatory veto coup—advertised low-cost circumcision via mobile health units.Footnote 25 Although many Islamic scholars in Egypt condemn FGC, Abu-Salieh (Reference Abu-Sahlieh and Abusharaf2006, p. 59) argues that the majority maintain that it is an act worthy of merit.

3.4 Findings from greater Cairo survey

This section has sought to describe broad, population-level patterns in the practice of FGC across Muslim and Christian communities in Egypt. We have shown that while there has been a decline in the prevalence of FGC among younger generations of Muslim women, a much steeper decline has been witnessed within Egypt's Christian community. Emphasizing the importance of coordination within religious communities for impacting social convention change, we provide a narrative account for how Egypt's Christian community has been relatively effective at encouraging norm change via top-down messaging from elites within the religious community regarding the harms associated with FGC. These efforts have been aided by relatively high levels of centralization within Egyptian church communities and high levels of contact between female parishioners and church leaders. We contrast this situation with the relatively diffuse, non-hierarchical nature of guidance regarding FGC within Egypt's Sunni Muslim community. While state agents, including state-sponsored religious elites, have largely discouraged the perpetuation of FGC, more conservative clerics and lay Islamist activists have emphasized the merits associated with female circumcision. This heterogeneity of opinion within the Islamic community has made it more difficult for Egyptian Muslims to coordinate around a new social equilibrium that eliminates FGC.

This section reports the results from an original survey that explores these issues in greater depth than possible through the Demographic and Health Surveys. The survey was conducted in 2014 in two neighborhoods of Greater Cairo in partnership with the Egyptian office of the Population Council, an international non-profit organization.Footnote 26 In each area, all Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) Primary Sampling Units (PSUs) were mapped and four were selected for inclusion in the study. We used a neighborhood saturation sampling strategy, in which the survey team canvased selected PSUs and enrolled eligible and willing women into the study. In total, 410 married women between the ages of 25 and 36 years old with at least one daughter were selected to participate in a face-to-face survey administered to no more than one woman per household.Footnote 27 We selected this age range to capture the possibility of changing FGC status for relatively young women; by interviewing married women up to age 35, we believed we may also have the opportunity to interview young mothers who were making choices about their own daughters' FGC status.

The survey was administered in two adjacent neighborhoods—Shubra al-Kheima and al-Khousus—which are located just north of the Cairo governorate border in Qalyubia governorate. Shubra al-Kheima and al-Khousus were selected for two reasons. First, relatively large numbers of Christians live in this part of Greater Cairo. By surveying women in this area, we were ensured the opportunity to survey enough Christian women to provide a reasonable sample for gauging attitudes. Second, surveying women in this area allowed us to examine variation across rural and urban areas; Shubra al-Kheima is urban while neighboring al-Khousus is more rural with agricultural fields interspersed with smaller villages.Footnote 28

The survey was described as being related to the future of girls and women in Egypt with a particular focus on health and education. In addition to questions about their educational and family background, women were asked a variety of questions about their health, including their FGC status and attitudes toward FGC. We report our findings with a particular emphasis on the difference between Muslim and Christian attitudes (see Table 1). We find that the vast majority of both Coptic Christian and Muslim married women 25–36-year-old in our Greater Cairo sample have been subjected to FGC (over 96 percent of Muslim women and over 83 percent of Coptic Christian women). These figures look very similar to national trends. FGC took place before the age of 15 for almost all of the women in the sample, most frequently between the ages of 9 and 10. When asked about their daughters, 3 percent of Coptic Christian women already had subjected at least one of their daughters to FGC while this figure was about 14 percent for Muslim women. When asked about intentions for the future, 4 percent of Coptic Christians had planned to undertake FGC for at least one of their daughters, while this figure was 32 percent for Muslim women.

Table 1. Summary statistics regarding FGC status and attitudes toward FGC from 2014 Greater Cairo survey, by religion

When Muslim and Christian women were queried about the role of government in banning FGC, we find that Christian women were more likely to see the government as having a role in banning FGC.Footnote 29 Although this issue requires more investigation, it suggests the possibility that changing norms within a religious community might buttress state-level efforts at criminalizing FGC.

As reported, the vast majority of Christians said that they were not planning to subject their daughters to FGC. Our survey allows us to understand more about the reasons women offered for why not. While some Christian women pointed to the fact that it was dangerous for girls, others said that it was illegal or no longer done. Even larger numbers said that they would not circumcise because of religion and because it is was not the right thing to do. For Christian women who said that they would engage in FGC, they most often stated that it was because of customs and traditions that led them to support FGC as a practice.

For Muslim women who already subjected their daughter to FGC, they reported that they had made that decision because of customs and traditions or religion. For those who said that they planned to engage in the practice for their daughters in the future, it was most often because of customs and traditions, religion, or to encourage daughters to be well-behaved. Muslim women who said that they would not engage in the practice for their daughters pointed to the fact that it was dangerous for girls, that it might negatively affect the girl psychologically or sexually, or that it was not the right thing to do. Very few said that they planned not to engage in FGC because of religion (particularly in contrast to the Christian trends).

Women were also asked if they believed their religious leaders wanted to end the practice of FGC, a question that speaks directly to the elite-led mechanisms of social change that we have described. While the vast majority of Christian women said that they believed their religious leaders wanted the practice to end, the majority of Muslims believed that this was not at all the case for their religious community (see Figure 3). Indeed, more than 50 percent of Muslim women in our sample said that their religious leaders did not want FGC to end at all. This evidence points to the importance of religious elites in encouraging or discouraging norm change. To explore the implications of a woman's FGC status for her future marriageability, respondents were asked about their preference for a circumcised bride for their male children. For Muslims, about 38 percent answered yes while only 6 percent of Christians answered yes to this question. Muslims and Christians also vary significantly in how they view the implications of FGC as related to women's behavior and husband preferences.

Figure 3. Survey Respondent Beliefs that Religious Leaders want to End the Practice of FGC, by Religion. Data were drawn from 2014 Greater Cairo survey.

4 Family-level socialization and attitudes toward FGC

Overtime trends in aggregate rates of FGC provide information about its persistence in Egypt. Data of this form, however, tells us little about decision making taking place within families as well as variation within religious communities. Families, and mothers in particular, face a variety of constraints and pressures when it comes to a decision of this sort. The decision regarding whether or not to circumcise one's daughter is one of critical importance, believed to impact the marriageability of girls in a society when economic options outside of marriage are highly limited. In this section, we explore the importance of exogenously-determined family structure in determining women's attitudes toward FGC even after taking into account important individual-level factors.

Table 2. Summary statistics for DHS 2008 and 2014 samples, by religion

4.1 DHS Data on Attitudes toward FGC

We use data from the nationally-representative 2008 and 2014 Egyptian Demographic and Health Surveys to explore the attitudes toward the continuation of FGC.Footnote 30 A first trend to point out is that Muslims, on average, support the continuation of FGC at higher levels than Coptic Christians (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Percent of DHS respondents (2008 and 2014 samples) who believe FGC should be continued.

Our main outcome of interest is a mothers' belief about whether FGC should continue or not.Footnote 31 In this analysis, each woman's belief appears as a binary variable, 0 if she thinks FGC should be stopped, and 1 if she thinks FGC should be continued.Footnote 32 Like existing studies, we hypothesize that having sons invests parents, to some degree, in patriarchal values [e.g., Washington (Reference Washington2008), Shafer and Malhotra (Reference Shafer and Malhotra2011), Glynn and Sen (Reference Glynn and Sen2015)]. Our key independent variable of interest is the gender of the first-born child. As the first-born gender is a dichotomous variable, throughout the analyses we will estimate the effect of having a first-born male. We believe that this variable serves as an exogenous form of variation since sex-selection is rare in Egypt; the prevalence of such a practice would be particularly low for first-born children.

We include a number of covariates in our analysis. The first is the total number of children born to a woman. We also include maternal education—the number of years the respondent has attended school—which has been shown to be highly correlated with a daughter's FGC status. For example, in a 1990 survey in northern Sudan rates of FGC among eldest daughters was over 60 percent among women with no education and about 30 percent among women with secondary school education.Footnote 33 We also include an asset-based wealth index created from information collected in the DHS household questionnaire to account for any residual SES effects.

FGC may be seen as a more desirable practice by women who were themselves subjected to FGC. As a result, we include a control variable for a woman's FGC status. In addition, FGC as a practice has been declining over time in Egypt. To control for time trends in FGC, we include a variable for mother birth year. Finally, we include region fixed effects for four regions with Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt divided into urban and rural areas. This creates a total of six designations, as specified by the DHS: urban governorates, urban Upper Egypt, rural Upper Egypt, urban Lower Egypt, rural Upper Egypt, and frontier governorates.

4.2 Empirical results

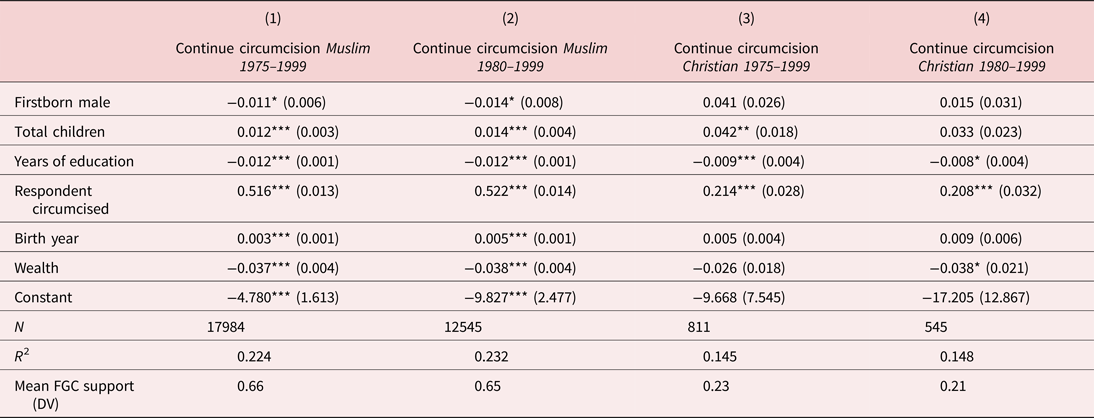

We estimate a linear regression model to analyze our dependent variable.Footnote 34 Since we are interested in how the effect of the first-born gender varies over time and for the two religious groups, we create several samples of older and younger Muslim and Christian women using birth-year cut-points beginning with 1975. Tables 3 and 4 report the main statistical results among older and younger women by religion, using different cut points to examine the relationship between first-born sons and attitudes toward FGC over time. We separately analyze Muslims and Christians as we believe that our independent variables may be impacting these populations differentially.Footnote 35

Table 3. Attitudes toward Continuation of FGC among older women

Notes: The dependent variable is attitudes toward the continuation of FGC. All models include region fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered by survey cluster.

*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.10.

Table 4. Attitudes toward Continuation of FGC among younger women

Notes: The dependent variable is attitudes toward the continuation of FGC. All models include region fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered by survey cluster.

*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.10.

We find that having a first-born male is a significant predictor of mothers' attitudes toward FGC among older women and is particularly strong among Coptic Christian women (see Table 3). For example, among the cohort of Coptic women born on or before 1980, having a first-born son is associated with more than 6 percentage point increase in support for FGC. The predicted rate of support for FGC is about 24 percent among those without a first-born son, and 30 percent among those with a first-born son, holding other covariates at their means. Coptic Christian women have overall lower levels of support for FGC when compared to Muslims, however. Other factors which are associated with higher levels of support for the continuation of FGC include if the woman was herself circumcised and, for Muslim women, her total number of children. Better educated and wealthier women are less likely to support the continuation of FGC.

Among younger women, however, the effect of having a first-born son differs systematically for Muslims and Christians (see Table 4). For younger Muslim women (i.e., those born after 1975), having a first-born son appears to have a negative effect on the belief that FGC should continue. In other words, a male first child is associated with decreased support for the continuation of FGC, a pattern which is reverse of that which appeared in our sample of older Muslim women.Footnote 36 This suggests a generational change in attitude that became increasingly apparent for women born in the late 1970s and 1980s. Our sample size is considerably smaller for Christian women; however, we continue to observe positive coefficients on having a first-born son. These effects are not statistically significant at conventional levels but do not indicate a reversal in the direction of the effect as we observed between older and younger women who are Muslim. Figure 5 summarizes the coefficient values for these effects.

Figure 5. Coefficient values for effect of first-born son on attitudes toward FGC by religion and birth cohort.

Together, these results suggest that there was a universal effect of having a first-born son on attitudes toward FGC among older women and that this effect was especially strong among Christian women. Among younger women, this trend declined or even reversed, primarily among Muslim women who may have come of age during the period of the Islamic Revival in Egypt.

4.3 Interpretation

Our results suggest important differences in attitudes toward women and girls in Egypt, dependent upon religious affiliation and generational cohort. Muslims, on average, support the continuation of FGC at higher levels than Christians. While Christians tend to be less favorable toward the continuation of FGC overall, our findings suggest that Christians are susceptible to the influence of exogenously-determined child gender triggers in forming attitudes on women's issues. Christians with first-born sons consistently support more patriarchal social norms than those with first-born daughters. While older Muslim women exhibit greater support for continuing FGC if their first-born child is a son, this trend reverses for younger Muslim women.

These results suggest the existence of at least two forms of patriarchal values within Egypt. Christians appear to be less supportive of norms that harm women and girls—in the aggregate—but more receptive to conservative beliefs when those beliefs are deemed to be consistent with their “interests,” defined as the interests of their first-born child. In other words, messaging from religious leaders appears to have reduced overall levels of support for FGC among Copts, but family-level factors can activate conservative views when it comes to responsibility for controlled female sexuality.Footnote 37

For older Muslim women, the first-born gender has a small, positive effect on the belief that FGC should continue but for younger women, this trend reverses. Younger Muslim women may be increasingly influenced by forms of religious conservatism which emerged in the 1970s and 1980s in Muslim societies, like Egypt, which tend to see the behaviors of women as key to achieving a moral society. Indeed, Blaydes and Linzer (Reference Blaydes and Linzer2008) characterize 46 percent of Muslim women in Egypt as holding fundamentalist beliefs. Such beliefs may be consistent with the high expectations placed on women within conservative social movements, regardless of whether or not they adopt costly markers of commitment.Footnote 38

These findings contribute to a large and growing literature on heterogenous attitudes within Middle Eastern communities with regard to the rights and burdens associated with gender.Footnote 39 Most notably, Kandiyoti (Reference Kandiyoti1988, p. 283) seeks to unpack the overly monolithic concept of patriarchy by examining the conditions under which economic modernization can lead to an “intensification of traditional modesty markers,” reflecting new forms of female conservatism.Footnote 40 The evidence that we have presented further complicates the ways in which religion and family structure in contemporary Egypt interact to construct attitudes and associated gender-related behaviors.

5 Conclusions

FGC is one of a number of practices that harm the interests of girls and women but which societies seem to perpetuate as a result of expectations about others' behaviors and normative beliefs (Mackie, Reference Mackie1996). Mothers and families often support these practices out of a desire to coordinate their activities with others and often become invested in a belief system that can bring harm to their female children.

In this paper, we focus on how meso-level factors related to a woman's family composition and her religious community impact both outcomes and attitudes toward FGC. Analysis at this level provides important insights into the nature of family pressures and religious group expectations that have been largely ignored in existing literature that has been focused on national and international efforts to reduce FGC, as well as individual-level socioeconomic determinants of FGC status. We show that Christian women in Egypt have seen a decrease in rates of FGC over time compared to their Muslim counterparts, despite having comparable levels of educational attainment in recent decades. Qualitative evidence suggests that Coptic Christian religious elites played an important role in affecting this change.

We also find that the gender of a woman's first-born child has an impact on her attitudes toward FGC but that this effect differs across religious groups and by birth cohort. Older women who have a first-born son tend to state their support for the continuation of FGC. We hypothesize that having sons invests mothers, to some degree, in traditional values that impact outcomes for female siblings in the family. For younger women, however, we observe a different impact of first-born child gender on attitudes. Younger Muslim women, many of whom were brought up in a political and religious environment which elevated the moral role of women as upholders of societal values, tend to support FGC less if their first child is a boy. Younger Coptic Christian women do not follow this same pattern.

Our results have implications for developing more effective policies for combating FGC in the future. First, our findings suggest that religious communities matter for changing attitudes. Religious elites can help facilitate the coordination of a new cultural equilibrium for their communities particularly if marriage markets operate within religious groups as occurs in Egypt. Second, different types of patriarchal beliefs may require different policy interventions in order to be effective. For traditionalists who support FGC more if their formative ideas about parenthood were influenced by the birth of a first-born son, interventions which stress the equality of men and women may be effective in reducing the salience of patriarchal beliefs. For younger Muslim women whose beliefs are influenced by the Islamic Revival in Egypt, however, messaging should seek to humanize the role that women play in promoting a moral society.